Confessional: Years ago, some time in the mid-1990s, I took up hockey again and played for two years in the nascent Saratoga Springs men’s hockey league. At the time this was one step up from pickup games. Mostly we played in an ancient barn-like wooden arena that, as it turns out, had been built on PCB-contaminated land that is now vacant (forever, possibly) and sewn with grass. I got so serious about this, I would drive to Troy once a week for skating lessons in a tiny private rink (also inside a barn). We would practice edging by skating round and round holding onto a metal hoop anchored at the center, first one way, then they other. One summer I went to a hockey camp run by professional hockey players. Of such things an old man still dreams. Four years ago I went back to the league and played one game. Awful.

Here’s is a Mark Anthony Jarman short story about playing Oldtimers Hockey in New Brunswick. (Okay, more confession: Once, long, long ago, I won the Canadian Oldtimers Hockey League Sportswriter of the Year Award — the high water mark in my literary career.) Mark is an old friend dating back to our days at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He’s from Alberta, lives next to the Saint John River in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where he teaches at the university. He plays hockey, wrote a hockey novel, has three sons, and was a regular pick when I edited Best Canadian Stories. He is the subject of my essay “How to Read a Mark Jarman Story” which originally appeared in The New Quarterly and can be found in my essay collection Attack of the Copula Spiders. He writes the wildest, most pyrotechnic stories of anyone I know. This particular story appeared earlier in Mark’s story collection My White Planet.

dg

———

Drive the night, driving out to old-timer hockey in January in New Brunswick, new fallen snow and a full moon on Acadian and Loyalist fields, fields beautiful and ice-smooth and curved like old bathtubs. In this blue light Baptist churches and ordinary farms become cathode, hallucinatory. Old Indian islands in the wide river and trees up like fingers and the strange shape of the snow-banks.

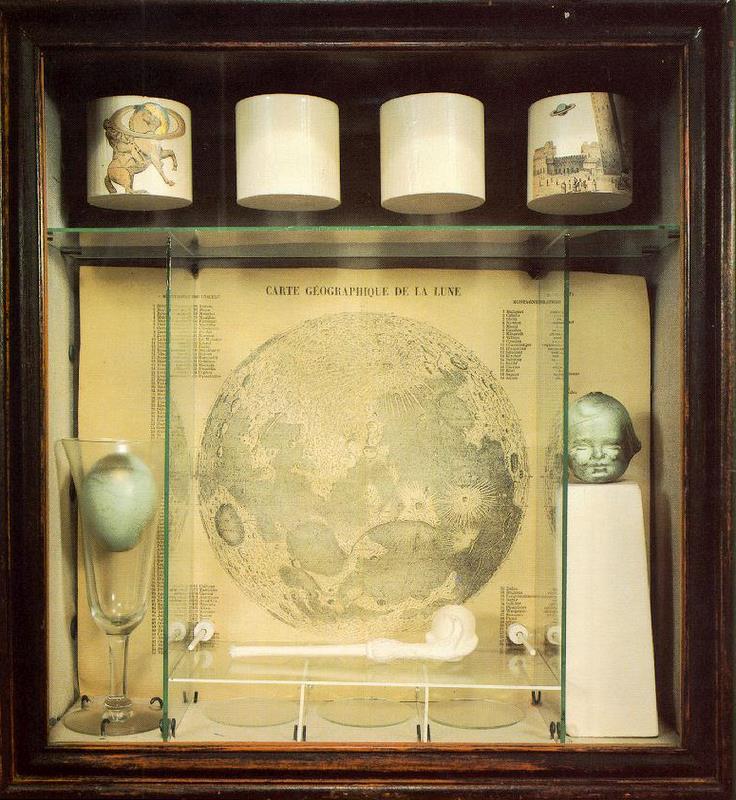

It’s not my country, but it is my country now, I’m a traveler in a foreign land and I relish that. The universe above my head may boast vast dragon-red galaxies and shimmering ribbons of green, and the merciless sun may be shining this moment somewhere in Asia, but tonight along the frozen moonlit St. John River the country is a lunatic lunar blue and the arena air smells like fried onions and chicken. We park by the door, play two 25 minute periods, shake hands, pay the refs, knock back a few in dressing room #5, and drift back from hockey pleasantly tired, silent as integers. And I am along for the ride.

Why do I enjoy the games so, enjoy the primal shoving and slashing and swearing and serious laughing at it all afterward? In these games I have taken a concussion, taken a skate blade like an axe between my eyes and I jammed brown paper towels on the cut to staunch the blood. Stitches, black eyes, and my nose is still broken from a puck running up my stick on its mission. Might get my nose fixed one of these days. One opposing player, when younger and wilder, is reported to have bitten another in the meat of the eye!

Today the inside of my thigh is a Jackson Pollock splatter painting: yellow green purple nebulas under the skin, flesh bruised from pucks hitting exactly where there is no padding (the puck has eyes). At night my right foot pulses and aches where I stopped a slap-shot years ago. My elbows are sore and they click when I move my arms. My joints are stiff when I climb the pine stairs, especially now, since yesterday I took the boys skiing and then I played hockey at night. Rub on extra horse liniment. My neck won’t move freely and a check wrecked my shoulder last April and for weeks I had to sleep on my back or the pain awoke me. Never got the shoulder looked at. I pay money for these injuries, these insults to my spirit.

So why pay, why play the game? As the Who sing, I Can’t Explain. Hockey is my slight, perverse addiction. Certainly I crave the physical side, especially versus working at the desk on 300 e-mails or doodling in a dull meeting. I enjoy the contrast, the animal aspects. I crave a skate, a fast turn on the blades.

And I play because I am a snoop. I learn things I would never otherwise know about New Brunswick, receiving a kind of translation, a geography lesson mile by mile, a roadmap, gossip, secrets, an unofficial oral history of this place’s lore and natives. My team translates and I am along for the ride, a spy in Night-town.

We ride the highway down from Nackawic where we always lose to the Axemen or the Bald Eagles, millworkers on both teams up there. I’m deep in the backseat of Al’s 4×4, but I spy a deer waiting by the shoulder like a mailbox. I point it out to Al at the wheel. The deer is hunched, nose out, poised to run across the busy lanes, its dark eyes inches from my face as our metal box blows past its snout and ears and private insects.

“I seem to hit one of those every two years,” Al says. “Wrecked more damn vehicles.” Al, as did his father, works fitting people with artificial limbs. The passengers in our 4×4 all hold bags of gas station chips and open beer — what we call travelers. I take up their habits.

Powder the goalie says, “I hit a deer last year and it was stuck across the windshield, this stupid face staring in at me in the damn side window. Damn deer’s fault, up in grass above, everything hunky-dory, and doesn’t it decide to cross right when I’m there. I must have drove 200 feet before the deer finally dropped off.”

“You keep it?”

“Didn’t want to get busted. 3 a.m. and I was drinking.”

“That’s when you keep them. Toss it in your freezer.”

“Ain’t got no freezer. Had to stop later at the gas station, headlights all pointed every which way.”

People are killed every year hitting moose on the road to Saint John. Off the highway there’s a moose burial ground where they drag the carcasses and scavengers have their way with the organs and bones. First they offer the dead moose to the Cherry Bank Zoo for its lions or tigers, I forget which. The moose the lions don’t eat end up in the pile off the highway.

Dave the RCMP says, “Man, when I was in Saskatchewan I was driving to Yorkton and came across this guy who had hit one cow square on, killed it, and he clipped another and it flew down in the ditch. It was still alive and I had to dispatch it. I come back up and this guy is crying about his van, some red Coca Cola van, vintage I guess, front all pushed in, big V pushed in, crushed the grill, and this guy is just fucking crying about it and I said, Mister, I’m here to tell you you’re lucky to be alive. But my van! Just fucking crying about his little red Coca Cola van.

Powder the goalie is in possession of beer stolen from the truckload of Spanish Moosehead ale. I’d like to have one can as an illicit souvenir.

“I’ll bring you some,” he says to me one game.

We do not let Dave the RCMP know this. Dave, also known as Harry and the Hendersons for his furry back, also known as Velcro for the fur on his back, gets a hat trick one night, four goals the next game. Velcro works hard. “Come hard or don’t come at all,” he says. Bad games he smashes his stick out of frustration, famous for ruining expensive sticks. Powder’s goalie gear is chewed up by his dog, same dog that ate his rug and his plants and his pet iguana.

After the game in the locker room no lockers, but a cooler full of bottles and ice or if there is no ice then snow from the Zamboni. My team stocks Propeller Bitter just for me.

“Any pussy drinks there left?” Thirsty the defenceman asks. “Pass me over a wildberry.” 6 or 7 empty bottles by him. He’ll drink anything. Takes a traveler with him for the drive. He’s not at the wheel; someone else is driving.

Thirsty was at the wheel on the road to Campbellton when his truck nearly went off the highway in a snowstorm, truck going sideways, going in circles on ice, his hands in deft circles on the wheel. They laugh about it now.

Big Billy says, “Thirsty’s arms were going like crazy, he looked like a cat digging in the litter box.” Both are good rushing defencemen, often way ahead of the forwards. Coach yells at them to stay back and play D. Thirsty complains of a lack of fellatio at home, complains that he’s living what he calls a no hummer zone. Or was that Big Billy the traveling salesman? They sit side by side and joke and laugh and drink.

“Getting no leather,” they complain, “getting no skin. Boys I tells yas, a woman gets married and she stops giving hummers.”

My wife says she likes the way I smell after hockey.

Get home late and buzzing and I can’t sleep, try to watch TV: Ringo says to an overturned rowing scull: “Come in #7, your time is up.” I am 50; how long can I keep skating? An 87 year old still skates for the Stinkhorns team. I am still waiting for the Oilers to call, say they need a stay at home D man.

Funny that I didn’t really start playing hockey until I was about 30, playing with jazz musicians on Sunday nights in Calgary. No helmets, few pads. I was a pylon. My nickname was Snepts. Then I played nooners with the Duffer Kings at Oak Bay Rec in Victoria for a dozen years. More and more pads, a helmet, then a visor. My nickname was The Professor. Same name here in NB. Maybe I should take up a pipe.

Some games are lighthearted, a lark, others are grueling, violent.

Across the river in Nashwaaksis I chase a loose puck behind our goal. #16 shoves me from behind, shoves me face first into the boards, exactly what players are told over and over not to do. Neck or back injuries, paralysis, broken teeth, concussions, low self esteem, etc. I get up yelling and pointing at #16 for a penalty, but it doesn’t matter as our team calmly gathers the puck, takes it down the other way and scores a goal. The ref points into the net.

In Burtts Corner two of us race to a puck rolling in our end. Different angles. If he gets the puck he’s in on net. I get close, swing my lumber and knock the puck away from their player, #10. He knocks my stick right out of my hands, yells, accuses me of hacking him. I played the puck, I know I made a good play. He’s just pissed off I caught up. When we’re all shaking hands after the game their goalie tells me, “#10 has gout. He was owly before the game even started.” Maybe he thought I was whacking his gouty ankles. What is gout? Some games I don’t shake hands.

“What are you doing to them back there?” a forward asks. “Someone is always after you.”

Ted says, “He gives as good as he gets.”

They all join in. “Oh he’s hacking and whacking, he’s clutching and grabbing like an octopus back there.”

I am innocent of all charges.

“That’s ok, boys,” says Ted, “that’s how we win games.”

Am I not a gentle soul? Am I not always on the side of angels? As Melville says in The Confidence Man, Many Men Have Many Minds.

A mining town. Some regulars are missing from our team: a wonky knee or sun-tanning in Florida. We look at the subs and judge our chances. If we can just keep it close, respectable.

Clean ice and we skate in circles warming up, loosen our legs and bad backs and eyeball the team at the other end as they eyeball us. Their goalie: is he good with his glove. Go low? Go high? Jesus didja see the size of his pads? I try to find reasons to dislike the other team. They ran up the score last game, made us look bad, they’re chippy, they probably like Bush, they probably kick orphans, their jerseys are too nice. The ref blows the whistle and we line up, see what the first shift reveals to us, the mystery of the first two minutes.

The last two minutes tick so slowly when you’re hanging on to a lead; the last two minutes slip past too fast when you’re trying to scrabble for that one goal, to change that arrangements of bulbs glowing inside a scoreboard.

We get mad when Barker’s Point runs up the score on us. A week later we run up the score on Munn’s Trucking and they get mad at us. Some nights we’re piss-poor, but some nights our A-team shows up and we’re smooth, raised on a diet of ball bearings and motor oil.

Drive the night, drive the hills and hollows and bridges. Ancient apple trees descend hills to the river in troop formation; arthritic looking, hunched over and no apples anymore. As in New England to the south, many pioneer farms are grown over or subdivided into Meadow Lanes and Exit Realty signs, which my bad eyes translate as Exit Reality.

Drive the daylight to a hockey tournament and huge potato barns rise out of the earth, doors into cavernous earth, part of the hill. JESUS HAS RISEN. Spavined barns sulk, sun and snow destroying each fissured shake and shingle and hinge, molecule by cedar molecule.

The boys like the tournaments up in Campbellton, the North Shore of New Brunswick. There they can cross a foggy bridge to take in the peeler shows on the other side of the water, watch what they term the Quebec ballet. More strippers and neon signs than in bible-belt New Brunswick. Last year Thirsty the accountant had a few and climbed up on a table and shimmied his own stripper dance, was disturbingly convincing. He likes a dark dancer, stares and ruminates. “Brown shutters on a pink cottage,” he says tenderly of her labial vicinities. “Man she’ll get you going, get you up so a dog can’t bite it and a cat can’t climb it.”

Balmoral, Matapedia: Scottish names and Acadian names on the highway signs and Franglais spoken in the bars.

A business-minded player on another team queries a woman as to how much money she makes in the Quebec ballet.

“125 a night, and ten of each dance is mine. I have a pager and a cel and hook for 150 an hour. I clear 140,000 tax-free in a year.”

One of the strippers writhing at the pole tosses off her leopard-skin g-string and Thirsty at ringside grabs her garment and hides it under his ball cap. Later she searches the stage for her undies. Where oh where is my g-string? He saves this item as a souvenir. Such behaviour is frowned upon in my other worlds, and this may be why I get a kick out of time lost in this world.

The ice is Olympic-sized, hard on the d-men with all that room to roam. But we don’t want to win too many games, we don’t want to get into the tourney’s final game because we’ll crawl home too late Sunday night. It’s a long drive from the North Shore. Ted misses an open net.

“Bet you boys were relieved,” he says. Ted is a tall drink of water, long reach, can corral the wildest passes. In the city he runs an old family car dealership. We lose 2-1 and are happy.

A crowded motel room, bodies stretched everywhere, hockey equipment everywhere, hockey on TV. Thirsty places a ketchup pack at the base of the closed bathroom door and stomps hard on the ketchup pack, trying to spray Big Billy inside the bathroom. The ketchup sprays all over Thirsty and in a fan up the beige door and wall.

My bottles of Propeller Bitter are gone down my throat. I steal the last Heinekin from Thirsty. He sits on a bottle: “Try and get this one,” he says. The second day we have a very early game at the tournament: some of the guys are already drinking at 7 a.m., bottles beside them as they don gear. Too early for me. We stink in that early game, but are giant killers in the afternoon game, knocking out a very good team that planned to roll right over us. There is no predicting.

Sugarloaf Mountain looms over the town. The Restigouche River, the Bay of Chaleur, ice-fishing shacks lined up like a little village. Snowmobiles worth hundreds of thousands of dollars are parked nose to nose outside our motel rooms; an intergalactic gathering, wild plastic colours and sleek nosecones and fins, looking like they’d rocket through space rather than over the old railroad routes that cover the snowy province. Someone is killed that weekend on a Polaris going 90 miles per.

The lazy joys of beer after we win. Griping and grousing and the lazy joys of beer after we lose. I see an eagle on the way home, arcs right over my windshield.

Limekiln, English Settlement Road, Crow Hill, Chipman, Minto, Millville. Narrow logging streams, dead mill towns. Elms fit the world, the winding country roads to country arenas, our headlights on the underside of sagging power lines, wires painted by our light.

Coach’s car slides a bit on black ice by the Clark hatcheries where the wind and snow scour the low road. Coach often gives me and Dave the RCMP a ride to the arena. Coach is a burly retiree in a ballcap and windbreaker, a former goalie and back catcher, ferociously competitive when he played and he cannot understand those who aren’t the same.

“Jesus I’m sick of it, they show up and don’t have a stick, they don’t have skates. Before I went out the door I’d make sure I had everything.” His relatives are buried around here, a graveyard in a cliff. He is a good driver.

“Been on these roads since I was a young fellow. Ice in the same places every year. Water runs off Currie Mountain and then freezes up.” Coach keeps a supply of mints in his glovebox. I sit in the back.

We skate our warm-up, Dave the D gazing up into York Arena’s old rafters, soon to be demolished. Dave is my new partner on D, works for Purolator, not to be confused with Dave the RCMP. Dave the D seems mild enough, is not imposing, but he is famous to older players as a former berserker. They talk about how he used to get right out of control fighting in the industrial league. Played in this arena for years. Now he skates around and looks about in a contemplative manner.

“Lot of memories?” I ask at the bench.

“A lot of punches to the head,” he says in a quiet voice.

Dave the D gets flattened late in the game. When he picks himself up I can tell he is calmly considering how to take it, what to do.

“Pick your spot,” I say.

“No, too old. I’ll get hurt and I’ll hurt someone else.” He sounds plaintive but smart.

After the game he dresses and leaves. We think he’s gone home. He flies back in the door later with a bottle of pop, surprising us, allows he was out in the parking lot.

“Thought I left that foolishness behind. Guess I didn’t.”

We look at his knuckles; is he kidding? Did he tune the guy?

“We wrestled a bit,” he says lightly.

I still don’t know what happened in the parking lot. In the summer Dave tossed his hockey equipment into a dumpster downtown; he decided it was time to stop, his body was telling him to stop, but he worried he’d keep playing just one more winter unless he physically got rid of his gear.

Rough hockey at Burtts Corner two weeks ago. A series of chippy games really, and I like them, I play better when there’s some turbulence, some contact. I don’t want to glorify being moronic, but it’s an adrenalin charge, a cheap thrill that makes me interested in what’s underneath the mask, the visor, underneath the charges and swearing and grand gestures. Is this a meaningless masculine pose; are we wanna-bes? Or is it what Ken Dryden calls learned rage, what is taught and approved? Or is it what waits in all of us just below the civilized veneer? I find it so easy to summon. It’s masochistic and childish, but I have to admit the threat of imminent violence is alluring (it’s fun until someone gets hurt, some childhood guardian intones inside my head). Maybe it just beats paperwork.

“You don’t belong in old-timers,” Coach shouts at the player who hacked me.

After the game we tease him. “Coach, you going out to the parking lot after that guy?”

“I could handle it. Growing up in Zealand no one’s a pansy, it was a tough life.”

He continues on the drive home.

“I have a cousin three miles up the road, he’s got to be over 70 now, but talk about tough, big big hands and long arms. Five years ago, so he’d be about 65 then, five years back two young guys from Kingsley were after him in Bird’s General Store, he was at a table, they knew his rep, he kept warning them and they kept after him and finally he gets up and BAM BAM, flattens both of them. He used to fight every Saturday night at the dance on Stone Ridge.”

Coach stares ahead and talks as he drives and hand out mints. The white river to our right, stars undulating above, and clusters of mercury vapour lights like coals spread to cool on a snowy hillside. In the back seat I clear a tiny porthole in the frosted window and feel like a child listening to stories.

Coach says, “When I was a kid my parents would go to the Stone Ridge dance. We had an old International half-ton and I spent a lot of time in that, sleep on the seat or get up and wander around, maybe the crowd would wake me up rushing out of the dance. They’d go this way and that way following the fight. I guess word got around and guys used to come up from Fredericton to fight him.”

It’s hard to imagine Coach as a little kid sleeping in the International at the Stone Ridge dance. Navigator has known Coach a long time, Navvy has played with some of our players since they were in grade school. He has horses, sulkies, and a bad back that’s making him miss most games this year. He works in a halfway house. Man coming back in the evening sets off a metal detector. Navigator navigates him to the doctor who will examine him. The doctor says there is a snub-nose pistol up his rectum. The doctor says to Navigator, “Want me to pull the trigger and save us all a lot of trouble?”

Navigator tells prison stories, says, “50% of women in jail are lesbians, 50% are dykes, and the rest are just wild!”

Powder the Goalie says a woman who lives down the road calls him up, bit of a burning smell in her trailer, she says. Powder goes over to see. The panel is hot, smoking, what to do? Goalie turns off the breaker, but the lights stay on.

“Oh, oh,” says Mike the insurance agent.

“Don’t call me, call 911. Three fire-trucks come out, and two hydro trucks.”

“She was a looker in high school,” says Danny.

“Field dressed she’d be about 350 pounds. Knees like this.” Powder holds out his hands as if around a fire hydrant.

Mike winces, shakes his head. “Field dressed.” Mike’s been on the team from way back, a slick skater. Mike and Ted play well together on a line. Big Billy calls them The Golden Girls. “Coach, who’s playing with the Golden Girls tonight?”

Our goalie puts the puck in our own net; he has done so several times. Bad game. Mike gives the goalie a dirty look. Ref skates over, plucks the puck from back of the net for the seventh time, says to our goalie, “Well the beer will still be cold.”

“You sir are correct.” Laughs.

Coach is not laughing, wants a new goalie. “He doesn’t have his head in it!” He’s going to watch other teams, look for a new recruit.

Coach is tossed out of the game in Oromocto. He stepped on the ice to yell “Fucking homer” at the ref. A bad ref. You can swear at the refs, but you can’t step on the ice. Automatic suspension. He walks off the ice in his city shoes: “Fucking homer! Fucking homer!”

The other team is puzzled; most old-timer teams don’t have a coach. “Who was that?”

Ted says, “You don’t know Scotty Bowman?”

Wheel! Wheel! Man on you!

Slow it down. Make a play.

That guy couldn’t put a puck in the ocean.

Up the boards, up the boards, the glass is your friend.

Don’t put it up the boards; make a play.

Got time! Got time!

Short passes, guys.

No centre line – hit the long pass.

16 slashed me, I’m going to kill him.

This goalie goes down right away; hang onto it and shoot high.

Shoot low boys, right on the ice.

I have to skate, love to skate, the action, the speed, feel physically uneasy if I don’t get a skate in. Navigator has to quit his hip is so bad. Pinky quits, Jerry quits, Mike quits, all the originals. When will I stop — that moment with your gear poised at the lip of the dumpster.

They don’t know your life, but they know whether you back-check, whether you try, whether you can pass on the tape, whether you paid your beer bill, who is the weak link, who to give the puck to, who has the touch, who is cool under pressure (not me), who has a cannon (not me also), whether you can be relied on.

The group can be superficial, callous, sexist, racist, homophobic, insensitive, but I don’t feel motivated to correct anyone. The range of our conversation, what is safe, is incredibly narrow and repetitive, i.e. Don’t bend over in the shower. We don’t discuss the new CD by Arcade Fire, we don’t dissect books or Hamlet’s worries, we don’t display our worries. There is a kind of censorship, but that is also true of my other worlds. In the group some may dislike me, but we are intimate, tied up in a camaraderie that is worth something, to shoot the breeze, use stupid nicknames, tell bad jokes, drink cold beer together in boxers, laugh at stupid stories, and delay going back to dress shoes and duplexes. Laughter is good, the doctors tell us. And win or lose, I laugh more with these guys, strangers really, than anyone else I know. When I moved to New Brunswick I wondered if it was a mistake, but I get home from hockey still laughing at some goofy story and think, This is a life, this is doable.

Gord Downie, the singer for The Tragically Hip, is hanging in Fredericton, auditioning for a hockey movie re-enacting the 1972 Canada-Russia series. He wants to play Ken Dryden or else Eddie Johnston, the backup goalie. I hope he gets a part. If I met Einstein at the Taproom I’d likely have little to chat about. Gord and I could talk hockey; hell, we could even play hockey. The crews film at Aitkin Centre and Lady Beaverbrook Rink will be the Russian arena.

“They still need Yvan Cournoyer for the movie. Anyone look like the Roadrunner? Know any French?”

My TV last year, before the NHL lockout; Vancouver was playing, maybe the playoffs; it all seems so long ago.

“Naslund is open. The offside forward has to collapse and help out.”

I can collapse. I can try to help out. But this is not our language. Coach just yells “C’mon boys!” over and over in a disgusted voice, an exasperated voice. This is the extent of our playbook.

“It’s such a simple game,” he moans. Coach gets mad almost every game, folds his arms over his chest and turns his big back on our game, refuses to run the door. It’s a simple game and a complex game.

Our cars cruise the Loyalist countryside, Acadian land, Maliseet land, prehistoric land; our cars drive up the river and turn into snowy corvid valleys, over covered bridges, past dark mills and swaybacked railroad stations where no tracks run, the rocky country the Thirteen Colonies dismissed as the tail and hooves of the ox. Over and over we line up at the circle. We pay 200 in November, we pay 200 more in January. We are driven. It’s like a devotion to winless horses.

Lace them up in an unheated pig barn. There is no crowd noise, no music. We play the game in silence except the players yapping at each other or at the refs. There are no cameras, but we play our parts, hit the marks. No one watches us, there is no first place, no last place, it all means little, really, but we keep playing. Our skates glide in silence and noise, we step lightly, fleetly, fall into each other’s airspace until the rink melts into grass. We don’t watch, we drive to the net. We drive and we play.

—Mark Anthony Jarman

—————————————–

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.