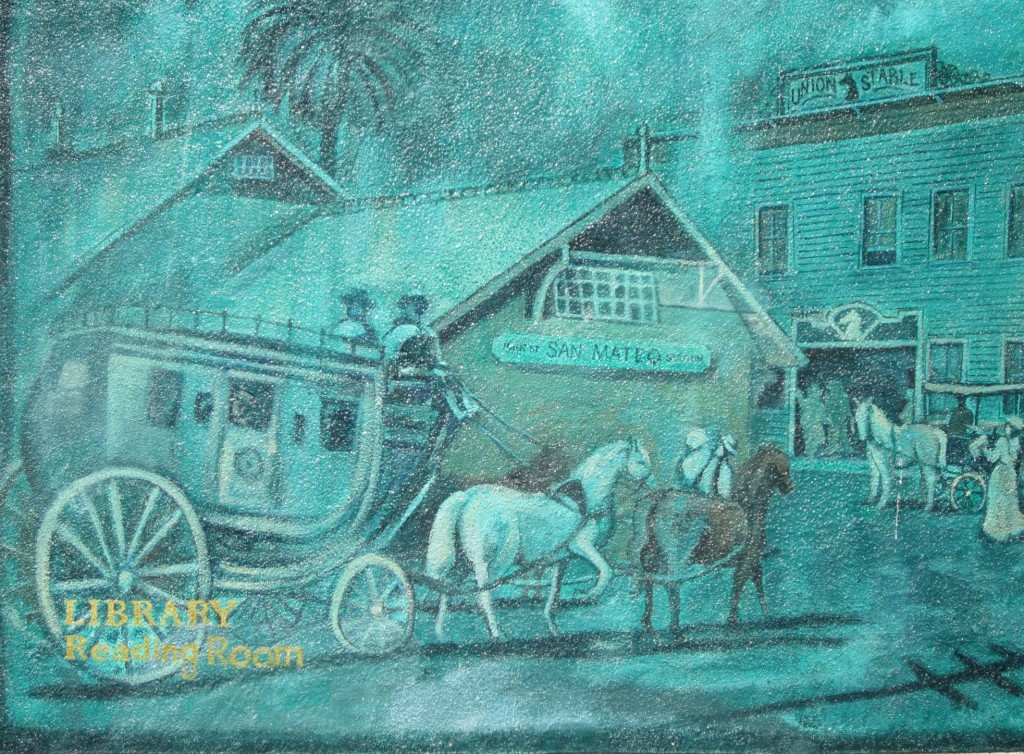

This is a treat, a gorgeous, frank, lusty, ever so subversively comic (it’s always slightly comic when women take a good look at a man) love story about — no, not that kind of love, but about a woman and her dog. I have known Caroline Adderson since, oh, before 1992 when I included three of her stories in that year’s edition of Coming Attractions (co-edited with Maggie Helwig). I will never forget that experience — I read five lines of a story and KNEW I’d found a writer, not just someone who pushed words around on a page efficiently but someone who ELECTRIFIED the language. And she has never disappointed since. Later I also put her in Best Canadian Stories. So we have an editorial past together, Caroline and I, and a friendship, and that makes it doubly pleasurable to bring her into the Numéro Cinq fold.

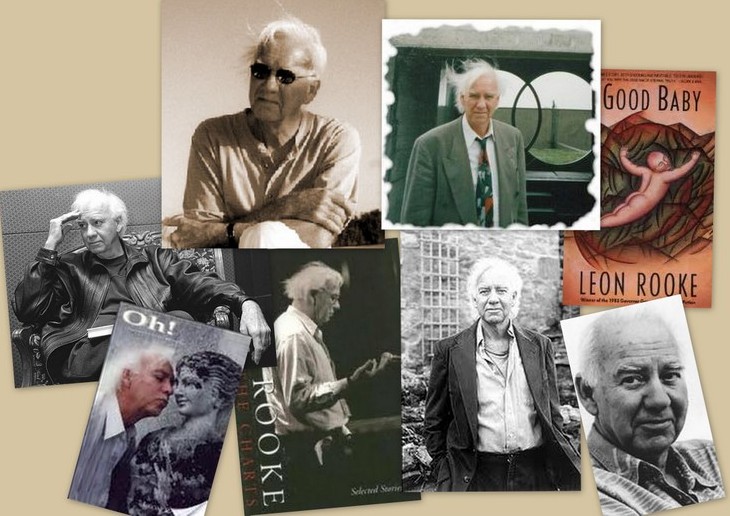

The story is gorgeous, yes, I should repeat that. It is stocked with felicities, large and small. One of the loveliest is the way Caroline weaves in a reading and rereading of Chekhov’s classic short story “Lady with a Lapdog” — a tale of a woman, a man and a dog, though as Caroline’s protagonist notices, the dog is not altogether considered as a character and seems to fade out of the story, a shortcoming that is rectified in the present story. (And to nail the point we have, above, a photo of the author and dog.) Caroline further complicates the story by introducing a younger male lover, a former husband and a wonderfully irate new wife (there is an amazing set of scenes around this pair — the author does not make the mistake of hiding the fact that the protagonist and her ex have slept together since the ex married his new wife, the new wife knows, her hatred is dramatic and comic, the scenes are charged with mischief).

And, of course, the dog can read.

dg

.

BACK IN OCTOBER Matt’s girlfriend had been out of town. Matt, unemployed, had hours (all day in fact) to lie around with Ellen who, living off her savings, was queen of her own life. Queen Ellen spread out in the loft on the hot twisted sheets, inhaling the tang of their exertions, while Matt scampered naked down the ladder to do her bidding. He brought her a glass of water, a wad of tissues to wipe the milty puddle off her belly, a cheese plate from the fridge.

She’d sold her house for a grotesque sum and inherited half of what her father had socked away in the life he cut short himself. Meaning Ellen could quit publicity and rent an old live-work studio in a Kitsilano triplex. One very large room, kitchen, bath, sleeping loft. She took up pottery again, put the kiln outside under an overhang. She took up with a man-boy in his twenties who wore shorts in any weather.

The things Matt said were so funny and sweet. Like the time he fell back on the pillows, his curls fanning out. “I need to ask you something really personal. I’ve never asked anyone before. I need the honest truth. Please.”

“What?” Ellen said. “What?”

“Is my cock too big?”

Now she was back. The girlfriend. Matt brought his cell phone up to the loft and left it turned on. Ellen pretended she didn’t see it tossed onto the clothes he’d so urgently shed. She pulled the sheet up to cover her body. Too much information, she thought.

What choice did she have? Ellen was 48. Too old to be anyone’s girlfriend.

§

Across the street from the studio was a corner store. This time of year Christmas cacti, poinsettia and little bonsai pines crowded the board and cinderblock shelves out front. Plants were the main business besides cigarettes and lottery tickets. Ellen worried it would go under so once a week she scooted across the street to buy something she didn’t need. Another plant to ignore to death. A can of corn. There was little else. The Frosted Flakes looked archeological.

She ran across in sweats and an old loose t-shirt scabbed with drying flecks of clay. The dog was shivering in a newspaper-lined box beside the till. She couldn’t tell its breed. The black kind with a goatee and plaintive eyes.

“Where did it come from?” she asked.

The owner of the store said, “My brother. Driving from Chilliwack? He saw it on the road. You want it?”

“I just came in for some corn.” Ellen set the can down, leaving fingerprints in the dust on top. “Maybe you should take it to the SPCA.”

He waved his arms back and forth like an air-traffic controller directing a 747 with batons. “Too busy!”

“Oh. Do you want me to take it for you?”

Ellen tucked the Niblets in the box with the small black dog and carried both across the street. Halfway, the dog reached up and licked her face.

“None of that now,” she said.

Hardly anyone got Ellen at first, but this dog did. He beat his feathery tail against the side of the box and smiled. When she shifted the cardboard carrier onto one hip and opened the door, he leapt right down, dashing circles around the studio, sniffing everything—Ellen’s pottery wheel, her dentist’s chair. He jumped onto the couch and tossed the cushions aside with his snout. Then he did what Ellen always did when visiting someone for the first time. He went over to the shelf and read the spines of all the books.

§

Matt didn’t come that day, or call—well, he never called. Normally this meant long unfocussed hours tied up in knots of hope, then, when Ellen could no longer deny he was a no-show, her dejected release from these self-wound coils. How pathetic to be waiting all day for a man as young as her daughters. Tear-stained, humiliated, she fashioned little monsters out of clay, then flattened them.

Today she put aside these pitiful recreations. She had to get a dog to the SPCA; to do that she needed a collar and leash. One thing led to another and, come evening, the dog was still there sniffing Ellen’s books.

She loved it too, that particular, melancholy odour of old paperbacks. It only followed then that the dog should have a literary name. (She had to call him something before she turned him in.) Tintin? Tintin was the boy, not the dog. What was the dog’s name? She googled it. Snowy.

Snowy would not do.

Lady with a Lapdog was right there on the shelf, perfumed in dust and sadness. The moment Ellen settled in the dentist chair to reread the story, the dog sprang onto the footrest, gingerly walked the double plank of her outstretched legs, then curled into a polite ball and fell asleep. A dog in the lap of a lady reading “Lady with a Lapdog.”

In the story the lapdog makes his appearance in the first paragraph, trotting along the Yalta promenade. No name, just a breed. A white Pomeranian. (This is ironic, for Dmitry Dmitrich Gurov thinks of the women he seduces as of the lower breed.) How many times had Ellen read this story of a passing affair that swells to a grand passion? Many, many times, and every time reminded her of her first reading at seventeen or eighteen, when she’d sobbed. With each subsequent reading, the sob returned, a ghost in her chest lodged too deeply now to release, her own heartaches grown around it, holding it fast. She’d been living with it ever since. Catharsis interruptus.

Tonight though, something was different. Something rang false.

A few days after first noticing Anna Sergeyevna, the lady with the lapdog, Gurov seats himself near her and the Pomeranian in an outdoor restaurant. He wags his finger at the dog and, when it growls, he appeases it with a bone off his plate. This way he secures Anna Sergeyevna’s acquaintance – through her dog.

After dinner, Anna and Gurov take a long walk, just as Ellen herself had done that afternoon when she returned home with the leash and collar and a hundred and twenty dollars worth of dog food and paraphernalia. What happened with Ellen was that the dog, the black one, the flesh-and-blood, tongue-and-tail one, made straight for the nearest tree and began to circle it, forcing Ellen to leave the sidewalk and slop around on the saturated verge. It was as though he was searching for something he had lost in the longer grass at the tree’s base, something he was desperate to recover. Finally, he found it, this precious thing invisible to Ellen, and when he did, he lifted a leg and pissed all over it. Then he romped ahead to the next tree where, evidently, he had also left something important in the grass.

After ten minutes of this Ellen grew impatient and tried to pull the dog along. He stiffened his legs, effectively putting on his brakes, and stared at her, ill-done-by. She had to coax and herd him, then pick him up and carry him. In other words, the entire walk had been about getting the dog to walk instead of sniff. More than once she got tangled in the leash, or he did. Yet when Gurov and Anna Sergenyevna go strolling after dinner, talking the whole time, marveling at the way the light falls on the sea, the dog isn’t even mentioned. Presumably he was there, or had they left him tied up back at the restaurant?

A week later, Gurov and Anna Sergenyevna retire to her hotel room to consummate their affair. Again, no reference to the Pomeranian. Does he object to their lovemaking? Is he jealous? Have they shut him in the bathroom? It doesn’t say. In fact, the dog is only mentioned once more in the story. Months after they both leave Yalta, Gurov finds he can’t forget the lady with the lapdog. He travels to her town, loiters in front of her house until, after a miserable hour, an old woman comes out with the Pomeranian.

Gurov was about to call to the dog, but his heart began to beat violently and in his excitement he could not remember its name.

Here Ellen lifted the real nameless dog out of her lap so she could return the book to the shelf. It was the first time the story had failed her.

Her epiphany came an hour later while she was brushing her teeth: the story was in Gurov’s point of view! It wasn’t Chekhov, but Gurov, who was indifferent to the dog beyond the purpose it could serve him in seducing a young woman. Whatever Chekhov may have felt about the canine species, Ellen knew this: if the story had been from Anna Sergeyevna’s point of view the dog would certainly have had a name. And a patronymic. And a diminutive, too.

So she settled on Anton. The resemblance was obvious by then—the longer black chin hairs, the compassionate tilt of the head. Couldn’t she just see him in a pince-nez?

§

In the studio window her pots flaunted themselves. Passersby could drop in and buy one. That was the idea anyway.

The next day Matt was out front getting rained on when Ellen and Tony returned from their walk. Her heart stuttered at the sight of his bare knees. According to the clock with movable hands on the back of her Come In sign, the sign she’d flipped to Will Return when she’d left with Tony, Ellen was late. This clock had proved useful in their affair, which was being conducted strictly on a drop-in basis; now it had provided Matt with a grievance. She pointed to her goateed excuse, though the goatee was not so obvious with the wet sock hanging down.

Matt asked, “What’s it got in its mouth?”

“A sock. Isn’t that cute?”

Before the door was fully open, Tony bolted in ahead of Matt, who threw back the dripping hood of his Gore-Tex and sampled Ellen, her mouth and neck. Only after they separated and shed their rain gear, did he ask whose dog it was.

“Well,” Ellen said, and she told him the whole story of bringing the dog home and the trip to the pet store. She might have been reading a script. Did he hear it? This was how she lived now, hovering above her own life, watching herself so that later, when she recounted her day to Matt, he would be amused.

“You would not believe what they had in that store. Look. Party balloon poop bags! I can coordinate Tony’s poop bag to my outfit. Or I can say, ‘I’m feeling existential,’ and take a blue one.”

Everything was in the box Tony and the can of corn had come across the street in. Matt reached for the plastic banana, squeaked it, and Tony snapped to attention.

“That’s a lot of stuff to take to the SPCA, Ellen.”

“And I hate shopping! I don’t know what came over me!”

“Let’s go up,” he said, starting for the ladder to the loft, pulling on her sleeve.

Ellen sashayed over to the sign and turned the hands of the clock forward another forty minutes, remembering how, not so long ago, their pleasure hadn’t been so stingily meted out, yet still feeling grateful, so very grateful.

§

She walked Tony to the vet, paid for shots and deworming, determined he was flealess. Wheaten Terrier, the vet thought, with a dash of Labrador. Maybe even a little Corgi. He lectured her on neutering.

Ellen said, “The thing is, I’m probably not keeping him.”

She should have been churning out Christmas pots, but couldn’t settle at her wheel. So restless! Ever since that debilitating conversation with her daughter Mimi, the one in Toronto, who had casually mentioned her Brazilian wax job.

“Everyone does it, Mom. No one would ever go around all hairy down there.”

Ellen was stunned. Another thing to fret about: her wild bush.

She started training Tony out of library books, glad to have found a use for all that corn. Tony was gaga for Niblets. Within days she had him sitting and lying down for Niblets, though no inducement would endear him to the leash. He was a free spirit and, respecting that, Ellen let him sniff along behind her.

On YouTube, she watched Pumpkin the beagle read. It really seemed that he could. When shown a picture of a cat and offered a selection of words printed on cards, Pumpkin selected C-A-T 100% of the time. Some old competitive streak surfaced in Ellen. She opened another can of Niblets.

Finally, finally, Matt dropped by. “Sorry,” he said.

“What for?” Ellen chirped.

“I couldn’t get away.”

Ellen pictured the girlfriend, not her ineffable face, but her tidy little Chekhov mound, pristinely waxed. All her thinking about the Russians had brought her to this unflattering comparison, that, pubically, Ellen was in the Tolstoy camp.

Matt said, “And I’m going home for the holidays. Did I mention that?”

One of the dog books explained stances, tail positions, barks. Ellen had noticed that, though Matt always said “I”, when he really meant “we” he cast his eyes down and to the right. And if she told him how desperate this news made her, would he ever come back?

“And where is home?” she asked.

“Spruce Grove. Outside of Edmonton.”

“Ah,” she said, feigning nonchalance. “I’m going away myself.”

He asked where, and she told him Cordova Island.

“Where’s that?”

“I used to lived there a long time ago. When I was married. My younger daughter Yolanda lives there now with her partner and their kids. She dropped out of pre-med to relive my life. The weird thing is, then my ex-husband moved back.”

“Oh,” Matt said. “Should I be jealous?”

Ellen laughed, but he didn’t. His face folded up in a way she hadn’t seen. He was always so uncreased, so playful, except when lamenting his penis size. It frightened her into blurting, “Oh! We’ve got something to show you!”

“We?”

It seemed he’d forgotten the dog until Ellen said, “Tony?” and the black head popped up among the couch cushions.

Ellen selected three books from the shelf—Lady with a Lapdog, Portrait of a Lady, Anna Karenina—books the average undergrad couldn’t tell apart. She stood them up on the floor. Tony waited, shifting from side-to-side, licking his lips, which Ellen knew now was a sign of anxiety. She showed Matt the index card with its neatly printed question: Which book did Chekhov write?

“Read,” she commanded, holding the card in front of Tony.

He pranced over to Lady with a Lapdog and brought it back to Ellen. For this, she rewarded him with a palm full of corn. Then she turned to Matt so he might – she hoped – claim his reward, too.

*

Bus to Horseshoe Bay, ferry to Nanaimo, bus up island to German Creek. Ellen pulled her suitcase—stop-start, stop-start—stones jamming the wheels, through the gravel parking lot to the government wharf where the ramp was angled at eighty degrees. And she remembered how, all those years ago, whenever they left Cordova Island or returned, it had seemed so difficult. Inevitably it would be low tide like this and Ellen would have to negotiate the ramp with all their groceries and bags and Mimi, just a baby. Ellen had needed a sherpa. And where was Larry? Why couldn’t he sherp? She let the suitcase go first, clutching its strap and the railing, inching her way down, thinking of Tony pulling on the leash. She’d left him with her neighbor, Tilda.

It was the same ferry, a metal tub with a covered freight area, rows of wooden benches inside. Ellen loaded her suitcase on. Eventually other passengers began arriving with backpacks and Rubbermaid tubs filled with provisions or the Christmas presents they’d come to the mainland to buy, stacked on foldable dollies. A group of strangers. It used to be that whenever she took the ferry, she knew everyone and they knew her and half of them had slept with Larry.

Last year Ellen had slept with Larry at the Winter Solstice party at Larry and Amber’s house. Amber had gone to bed early with cramps. The island was full of this secretless type of woman, their menstrual cycles public knowledge. Ellen used to be one herself, though last year she took this information to mean that Amber’s body, if not Amber, accepted that these intermittent reunions between Larry and Ellen were, then, Ellen’s only opportunity for sex. That was Ellen’s point of view anyway, that she threatened no one.

And this year? This year Ellen was besotted with Matt, who kept coming around. Whatever his reason, apart from sex, was his secret.

The ferry backed out of its berth. A seal watched, head and shoulders out of the water, then ducked. Gulls screamed in a wheel above the dockside fish store. Ellen had quite forgotten the Solstice Party until now. During Ellen and Larry’s marriage, when she’d learned that friends of hers had slept with him, she’d shrieked, “How could you?” Very easily, it turned out. As easily as Ellen slept with Matt, rationalizing all the way: Ellen didn’t know the girlfriend. She was young. She would pity Ellen if she knew.

But Ellen knew Amber. She was practically related to her.

Tossed in the bag with the Christmas presents, Lady with a Lapdog. During the crossing, Ellen took it out, sniffed it, ran her fingers over the dog-Braille inside the front cover. She’d intended to reread the whole book, but instead found herself back with poor Anna Sergeyevna, stuck in love with Gurov, a man who classifies the women he sleeps with according to three types: Carefree, good-natured women, whom love had made gay and who were grateful to him for the happiness he gave them; those who made love without sincerity, with unnecessary talk, affectedly, hysterically; and two or three very beautiful women whose faces suddenly lit up with a predatory expression, an obstinate desire to take, to snatch from life, more than it could give.

This last type were no longer in their first youth.

And Ellen? Which type was she? Grateful and utterly sincere, yes. But it was true, too, that she was chatty in bed and freely voiced her pleasure. And that in two years she’d be fifty.

Then she felt it, the sob that could never be released, pressing hard behind her ribs. She put both hands over the place at the same time she glanced out the window, glanced at the precise December moment out on the open ocean with the solstice approaching when the colour of the sky and the colour of the water merged and there was no light anywhere to orient her. The great gray middle of her life.

The sob absorbed back inside her body. Next time she looked, it was night.

.

Her son-in-law, Sean, picked her up in the truck. They drove the main road, companionably, Ellen recovering from the shock of winter darkness. Off the grid, the island shut down on these long, overcast December evenings. They passed the Post Office, the Arts Centre, the Free Store, but Ellen couldn’t see them, only the forest in the headlights. She marveled that Sean knew on which rutted lane to turn. Then they bounced along, cedar boughs brushing against her window, spookily, like the memories of her former life here clawing to get in.

Eli ran out of the cabin when he heard the truck. “Nonny!” He was seven with wild clown hair he’d got from his father, who hid his under a toque. He dragged Ellen inside and when Sean brought in her suitcase and set it down, Eli looked from it to Ellen.

“Did you bring me a present, Nonny?”

Yolanda came over from the stove with baby Fern in a sling on her back, tsking at Eli, her glasses half-fogged from cooking, exhausted and angelic in her half-hearted ponytail.

“Give me that baby right now,” Ellen said in the middle of their hug.

Yolanda loosened the knot on her chest and Ellen waltzed Fern over to the couch lumped with sleeping cats. “Eli, come here,” she called. “I have some news. I have a dog staying at my house. His name is Tony. And you will not believe this, but it’s true. He can read.”

“I thought we were cat people,” Yolanda said, back at the stove.

“Where are our presents?” Eli asked.

“Don’t give in to him. He has to wait.”

“Why should you?” Ellen whispered. “Bring me that bag next to my suitcase.”

In it was Lepus arcticus. Arctic Hare.

At dinner, Ellen told them about her neighbour, Tilda, the fabric artist. “She knits iconic Canadian wildlife. She spins the yarn herself.” The white hare perched on the table dangerously close to Eli’s bowl of chili. “That’s why he’s so soft,” Ellen told him. “He’s got real bunny fur mixed in with the wool.” She didn’t want to say what the hare and the tiny Townsend’s Vole she’d bought for Fern had cost. “They’re not really toys. They’re works of art.”

Yolanda said, “The Solstice Party’s at Mason and Spirit’s place this year. And Amber invited us over tomorrow night. Do you want to go?”

Likely Ellen blushed. She fanned her face, pretending the chili was too hot. If she said no to Amber’s invitation they would wonder why.

Sean was trying to get Fern to eat a bean, washing the sauce off in his mouth, spitting out the bean and feeding it to the baby by hand. At the same time, he glanced at Ellen and smirked.

“What?” Ellen said.

Flapping his hands on either side of his toque, he cawed, “Amber alert! Amber alert!”

Yolanda slapped him on the shoulder.

“What does he mean?” Ellen asked, but Yolanda wouldn’t say.

Before bed Ellen read to the children, then stumbled in the starless dark to the outhouse and back. Calling goodnight to Yo and Sean, she retired to the tiny, frigid room, the one too far from the woodstove, less a bedroom than a pantry lined with dried beans and canned preserves. The cats joined her, bed warmers, slipping out later to kill.

Last year she’d lain in this same rack of a cot listening to the ocean’s restless exhalations, wondering what would happen between her and Larry. This year, the ocean was still exhaling, but the hands that moved over Ellen were young.

.

“When I say walkies he grabs something that smells like me. A sock. Once he headed out with my panties.”

Yolanda asked, “Are you keeping him or not?”

“I didn’t plan on it. Now I’m in something of a situation. Because I care about him. I can’t stop thinking about him. Like now. Talking about the dog counteracts the pointlessness I feel going for a walk without a dog.”

They were following a rocky trail through the woods down to the beach, Fern in the sling wearing a bright Peruvian cap with ties, twisting her head back to look at Ellen, Eli marching ahead pretending to shoot things while Yolanda intermittently called out, “Cease-fire!”

“I should give him up. I’m not getting any work done. I feel like I’m being dragged around by the hair.”

“Sounds like you’re in love,” Yolanda said.

Ellen halted in the middle of the path with her mouth open, her hand clutching her heart. Was she in love? The other hand reached for the support of a tree. She leaned in, pressing her forehead to the rough bark.

“Mom? What’s wrong?”

Yolanda hurried back and slipped an arm around Ellen. Fern’s small hand patted her head. It felt like the touch of a crow’s wing, over and over.

“Are you depressed?”

“No.”

“Last night I thought you looked so beautiful when you came into the cabin. You looked so happy.”

Ellen looked up. “Did I?”

“Yes. Sean even said so. He said you looked hot.”

“I love that man,” Ellen said, wiping her nose on her sleeve. “I’m—”

No, she was too embarrassed to confess.

“I know,” Yo said. “It’s the holidays. They get me down, too. Maybe we shouldn’t go tonight.” Her lips brushed Ellen’s cheek.

“Go where?” Ellen asked.

.

Yolanda went ahead with the kids in the truck while Ellen and Sean walked over with flashlights, Ellen hugging the ditch. Any old draft dodger with one headlight and a medicinal marijuana permit could round the bend, but Sean strode fearlessly up the middle of the road the way he would, on any dry day, streak down it in a death-defying crouch. He custom-made longboards and sold them on-line, or bartered with them. Somehow the boards, their Child Tax Benefit payment, and Ellen’s occasional cheques sustained them.

The glowing glass lantern of Larry and Amber’s house appeared through the trees, the opposite of Yolanda and Sean’s cabin. The opposite, too, of the shack where Larry had once lived with Ellen. For over twenty years Larry had written for television. This house, architect-designed, cathedral-ceilinged, powered by the sun, was built on sit-coms. You walked right into the heart of it where Amber was, at the stove talking to Yolanda, but falling silent when she saw Ellen coming over. She’d changed her hair, sheared the sides and beaded the long part on top. “Nice,” Ellen said, smiling and opening her arms.

On Cordova Island the standard greeting was a hug. You hugged the postmistress when she handed over your mail. You hugged the man who filled your propane tank. When Amber turned away, Ellen stood there, bewildered and stung.

She tried again. “What are you making?”

“Latkes.” Amber transferred one out of the pan onto a paper towel-lined plate.

The first thought that came to Ellen: “I have the best latke recipe. Grind the potatoes in the food processor. Then they’re fluffy instead of rubbery and don’t look so grey. Do you have a food processor?”

“No,” Amber said.

“Are we doing Chanukah?”

“No,” Amber said.

“Can I help?” Ellen asked, sincerely.

“No,” again, just as a latke slapped the floor. When Amber bent to pick it up, her thong showed.

“I see London, I see France,” Ellen said and Amber straightened with a look of such undiluted hatred her monotone trio of “nos” sounded furious in retrospect.

Ellen backed up all the way to where Yolanda had escaped to nurse Fern in the big armchair by the fire. She sank down on the hearth. Amber was never really warm with Ellen, understandably. Her best friend’s mother was also her husband’s ex-wife, but they’d always muddled through. Now Ellen, who had only expected to feel, along with the usual awkwardness, the guilt anyone would feel returning to the scene of a crime, was confronted with a hostility whose source she quailed to guess at. Amber was the one who’d invited Ellen. Yolanda had said so. Why would Amber do this if she knew what had happened between Ellen and Larry last year?

“Where’s your father?” Ellen asked Yolanda.

“I don’t know. Sean’s checking on Eli in the bath.”

They came over once a week for this purpose, Ellen remembered, trying not to panic. Because Sean and Yolanda would take a bath, too, probably together, while Larry hid in his study, like now, leaving Ellen alone and defenseless against Amber.

“Sure you’re okay, Mom?” Yolanda asked, touching Ellen’s knee.

Larry didn’t show himself until dinner. Unshaven, in slippers and a stretched-out cable-knit sweater, the kind on offer in the Free Store, covered with pills, he finally appeared. At the sight of Ellen, he drew his head back sharply, which confused her. Also, she didn’t know if she should hug him with Amber right there carrying the plate of latkes over to the table they were all gathering around and, instead of setting it down, letting it drop the last two inches so it clattered.

Ellen decided to behave normally and hug Larry. The sweater was pungent with old wood smoke. Strange how different his once-loved body felt when for all these years it was everyone else’s body that felt strange. All those lovers who weren’t Larry.

Then her second epiphany happened. Her second in as many weeks, when most people don’t experience two in an entire lifetime.

She took her place at the table, beaming.

Last year, and the year before, over the last quarter century, in fact, when she knew she would soon see Larry, she would always be in some kind of state. Excitement sometimes, often rage. At any rate, some form of passion would carry her away. But this year? This year all she felt looking across the table at the delicately made, silvering man who had ruled her heart for decades was a mild irritation that he couldn’t be bothered to put on something presentable.

She raised her wine glass. “Cheers.”

.

“It’s not you,” Yolanda told Ellen after they had got through the incredibly strained meal made bearable to Ellen by her own inane chatter. No one else would step up to the plate and talk. Except the children. Fern had blatted her few words, then guffawed as though she’d cracked a joke.

Ellen, with much nervous lip-licking, had explained how to teach a dog to read. “Take soap. Rub it on the card with the correct word. Rub the corresponding picture or object. Leave the other pictures unsoaped. What the dog is actually doing is reading the smell. That’s what smelling is for them.”

Eli asked what grade Tony was in.

(Lying with Matt, listening to Tony singing at the bottom of the ladder, she had used Lady with a Lapdog to teasingly fan his face. “Aren’t you curious how I taught him?”

“I know how you did it,” Matt had said. “That’s the book with teeth marks all over it.”)

Amber wouldn’t make eye contact, even when Ellen complimented her on the latkes, which were in fact rubbery and grey. Neither would Amber look at Larry. Instead, she shot secretive glances at Yolanda as though the two of them were teenagers.

Yolanda and Ellen volunteered to do the dishes. In the kitchen, the window ledge above the sink was crowded with driftwood and shells and coloured bits of beach glass. Also two rubber duckies, one with a bowtie, the other in a flowered bonnet. Ellen wondered about the pretty detritus, the shells and glass, things you’d pick up on a beach holiday to take home as mementos. What possessed Amber—it had to be her—to gather and display things so commonplace to island life? Ellen pictured her moping down at the beach, noticing a shell, and stooping. And in her mind’s eye, Ellen saw the thong again, the world’s most uncomfortable undergarment, and was glad, very glad, no longer to be young.

“Dad told Amber—” Yolanda whispered and the plate Ellen was washing very nearly slipped out of her hand, “—that he didn’t find her very interesting.”

Ellen exhaled, relieved. “Why is she so mad at me then?”

Yolanda said, “It’s not you. She’s mad at Dad. See how the boy is facing straight ahead?” She pointed to the duckies. “That means Dad wants to make up. But the girl has her back to him. So Amber is still pissed off.”

“Are you serious?” Ellen asked.

Yolanda picked a dripping plate out of the rack and, covering her face with it, giggled.

When the dishes were done, Yolanda went out to the greenhouse with Amber, ostensibly so Amber could smoke. Sean was in the bath with Fern. This left Ellen and Larry effectively alone, except for Eli, who was walking on Larry’s back.

“Why do you like to get stepped on?” Eli asked.

“It’s what I’m used to,” Larry said.

Ellen snorted. Soon Eli lost interest and scampered off to look for his arctic hare, leaving Larry face down on the rug.

“Those are great kids,” Ellen said. “It’s nice you see so much of them.”

“I’m wanted for my indoor plumbing.”

“More wine?” She went to the kitchen for it, found Eli crouching behind the island counter with the hare that had cost her $350, its face stained with chili now. He’d discovered chopsticks in a drawer and was carefully inserting them between the stitches into the animal’s body.

She returned with a glass for Larry, too. By then he’d resurrected himself and was stoking the fire, stabbing the burning logs with the fresh one. “Did you lose weight?” he asked.

“No,” Ellen lied.

Larry closed the fireplace doors. “You seem happier.”

“You don’t. And your sweater is ugly.”

She felt sorry for him, the way after seven or eight readings she began to feel sorry for Gurov, shackled by bitterness. Every new affair inevitably grew complicated and problematic; love always became an unbearable situation. When Yolanda moved here to be with Sean after Eli was born, Larry visited them. His visits to his own children had been infrequent, but now that he was a grandfather, he came. At some point he decided to move back, possibly when he met Amber. Ellen had never asked, but now she did.

There turned out to be a story. The way Larry offered it up made Ellen think he had been waiting a long time for someone sympathetic to lend an ear, and that no one had until now. Until Ellen. It concerned a play Larry had gone to see in L.A. five years before.

“A play everyone was raving about. By a young playwright.”

“A woman.”

Larry nodded. “It was pretty good. I liked it. The playwright was there so afterward I went over and introduced myself. She didn’t know who I was.”

Ellen sensed what was coming. She disguised her cringe with another sip of wine.

“I told her about Talking Stick and the awards it won and my TV projects.”

“Talking Stick was a great play,” Ellen said. “Your best.”

“I only wrote two plays,” Larry said.

“That was my favourite.”

He looked at her. Larry had a look like a taser. It disabled you with feelings of stupidity and self-doubt, but Ellen had been looked at by Larry so many times over the years she was as desensitized as a lab rat. “And?”

“That’s it,” Larry said. “I told her who I was. She didn’t have a clue. She’d never heard of A Principled Man. It ran two seasons. I was head writer. Curve Ball?”

“That was the baseball show?” Ellen asked.

“Curve Ball drew a blank, too.” He scratched his stubble then admitted that he had asked the young playwright to go for a drink sometime, not necessarily that night. “‘To talk about your play.’ I said I had a few suggestions. Well. She took gross offense. It was unbelievable how she over-reacted. Like I’d just said her play was shit, when I’d said the opposite.”

“Unbelievable,” Ellen said, thinking of Tony in full snorkel mode at the base of a tree. Now that she’d read all those dog books, she knew what he was so desperately seeking there. Some other dog’s three-week-old piss to dilute with his own.

Amber appeared out of nowhere then with Yolanda behind her. “I’m going to bed,” she announced.

“See you,” Ellen sang. “Thanks for dinner.”

Larry looked at Amber and, on her, it had its intended effect. She swung around and stomped off like a little girl, her beads clacking.

Yolanda said, “I’m just taking a quick bath, Mom. Do you want to walk now with Sean and Fern or come later with me and Eli in the truck?”

“We’re talking,” Larry told her.

“Well, don’t talk too much,” she said to Ellen.

“Gotcha,” Ellen said, sitting up straighter.

“The last time I wrote something decent was when we lived here,” Larry said, as though these discomfiting walk-throughs hadn’t happened. “That’s your answer. That’s why I came.”

“So how’s the play?” Ellen asked.

“There’s no play,” Larry said, and he turned and opened the doors of the fireplace and slammed another wood chunk in.

“Did you tell Amber about last year?”

Larry said nothing.

“Larry? You shouldn’t have. She’ll tell Yolanda if she hasn’t already. And now she hates me. Is that why she invited me? To show me that she hates me?”

“It’s a test,” Larry said.

Ellen threw up her hands. “It was nothing.”

“Was it?”

The way Larry looked at her then was entirely unfamiliar. There was a softening in his eyes. She saw his pain, too. His back, and now his play. Larry had always had a tortured process.

“My therapist?” Larry said. “The one in L.A.? He used to say, ‘Larry, you are addicted to Act One.’”

“What does that mean?”

“I like beginnings. When I lived with you? Here? That was the only time I ever finished a play.”

Ellen stared at him. The sweater made him seem shrunken. Both hands pressed the small of his back. Also, now that his legs were stretched out in front of him, she saw two different colour socks, black and brown.

Larry stood. Last year she’d followed him to his office, to his battered leather couch calicoed with the stains of his former conquests. But not then, not during any of the other times through the years that they had coupled up for old time’s sake, or relief, had he ever indicated that she might be his muse. Now he limped out, leaving Ellen by the fire in the lonely cathedral of the room wondering where everyone had got to and how they’d ended up this way, so miserable.

Well, the children were all right, and Sean, too. Yolanda was just tired.

“Nonny!” Eli called.

Ellen went to him, still behind the island. He held up the hare impaled with chopsticks; it resembled a voodoo doll. Laughing, Ellen lifted him and set him on the counter next to the sink.

“Look at these two,” she said, showing him the duckies on the windowsill. She made the girl ducky fight the boy ducky and Eli laughed. It was laughable. Pathetic.

Then she turned the girl ducky so it faced the boy ducky, so it seemed to be nuzzling the boy ducky’s neck.

.

Something happened just as they were leaving that changed the entire holiday for Ellen. Larry, when summoned by his daughter, shambled out to be hugged by her, then Ellen. Having helped the squirming Eli into his coat, Ellen pulled her gloves from her pocket. And something fluttered to the floor, something orange that Larry bent, wincing, to pick up. To her amazement, and Yolanda’s apparently, he straightened with a smile, his first that evening and, for all Ellen knew, that year.

A poop bag.

“I know what’s different about you, Ellen,” he said. “You got a dog.”

Did it count? Could this be a third epiphany?

She loved that dog! She would forget Matt. Forget Larry. What did they, or any man, ever do for her? She was always giving, giving herself away. No more, she decided. No more. She would get Tony neutered and live with him instead. Long slow walks in the morning, reading together every night. In between, a little bit of squeaky banana and some fetch. The second half of her life unspooled before her like a newsreel, its blazing headline: Contentment! Contentment!

After that Ellen just had to speak to Tony. She called Tilda from the truck.

Tilda said, “Yesterday there was so much corn in his poo. Today he’s better.”

“Have you been practicing with the Henry James?”

“Um,” Tilda said.

“Where is he?”

“Right here. He’s sleeping.”

“Put him on. Tony? Hi, Tony! Whatcha doing? Do you miss me, Tony? I sure miss you. What’s he doing, Tilda? Does he know it’s me?”

“He’s wagging all over the place.”

So who was Ellen’s grand passion? She wondered this after she hung up, in the truck bouncing back to Yolanda and Sean’s. Of course it was Larry. It had always been Larry, her Gurov. (But this was only her point of view. Larry, of course, would have a different opinion. He always did.)

Then this past October she found herself standing in line behind a man whose shirt tag was poking out the back of his collar. She tucked it in. He turned and said, “Your hands are cold.”

Your hands are cold. Your hands are cold. Let me. Warm them. Let’s go up.

She hadn’t told Larry, though she’d planned to. She’d planned to say, “See? I, too, can snatch this from life.”

Then, what with the Winter Solstice party and Christmas and visiting old friends who still lived on Cordova Island, Ellen did forget Matt. She barely thought of him after that night at Larry’s. Things were getting complicated between them anyway, especially now. Now that she had Tony.

.

When she got home to Vancouver, he was waiting for her. Tilda opened the door and he leapt against her legs and dervished all around her. The whole dog wagged. He wagged for Ellen.

She threw her bags inside and out they went. Tony sniffed and peed, sniffed and peed. Reaching the end of the block she turned; he was far behind. But all she had to do was call his name and he ran right to her, tongue out.

A child’s pink purse lay in the gutter in front of the corner store across the street. Ellen wiped it on the grass and showed it to Tony, who took the handle in his mouth.

In the next block, an elderly woman came along. “What in the world is he carrying?”

“We’re just coming back from Saks,” Ellen said. “Gucci’s on sale.”

“Well, he is cute.”

“Smart too. This dog can read.”

The woman’s face crinkled all over when she smiled in a way Ellen found very beautiful.

Back home, the mail was in a drift behind the door. She unpacked her suitcase first—she had bones for Tony—then checked the beeping phone.

“Ellen? Are you back? It’s Matt. I’ve been calling and calling. I really have to see you. I have to.”

She pressed the phone against her ribs, pressed it hard, but it wasn’t any use. It had been building all this time. And out it came. Out and out and out.

Tony laid back his ears and cocked his head to one side, but both of them knew because both of them had read the story. The end was still a long, long way away and the most complicated and difficult part was only just beginning.

—Caroline Adderson

.

Caroline Adderson is the author of three novels (A History of Forgetting, Sitting Practice, The Sky Is Falling), two collections of short stories (Bad Imaginings, Pleased To Meet You) as well as books for young readers. Her work has received numerous prize nominations including the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, two Commonwealth Writers’ Prizes, the Scotiabank Giller Prize longlist, the Governor General’s Literary Award and the Rogers’ Trust Fiction Prize. Winner of two Ethel Wilson Fiction Prizes and three CBC Literary Awards, Caroline was also the recipient of the 2006 Marian Engel Award for mid-career achievement. She lives in Vancouver.

.

.

Bromeliads with Red Blossoms

Bromeliads with Red Blossoms Hospital Heart Monitor

Hospital Heart Monitor Green Anole

Green Anole Sunlight on Wall with Euphorbia

Sunlight on Wall with Euphorbia Agave Stalk and Telephone Pole

Agave Stalk and Telephone Pole Why I Live in the Sky

Why I Live in the Sky Bougainvillia

Bougainvillia Gator in Pond

Gator in Pond Hawk

Hawk Raccoon in Humane Trap

Raccoon in Humane Trap Magnolia Blossom

Magnolia Blossom