Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Among the Long Shadows

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Among the Long Shadows

This is the fourth and final chapter in Paul Pines’ book-length essay on the Fisher King of legend. You can find the earlier essays in the NC archives, but for easy reference, here are the links.

.

Parzival felt all the grief he had encountered since he first began his long journey into exile from true innocence of heart. And in the same moment of anguished illumination, he saw how—mile after mile, day after day, battle after battle, until he had finally met defeat at his brother’s hands—that guilt-driven journey had taken him further and further from the one true source of joy and meaning in his life. Reflecting on his pride and bitterness, the willful error of his ways, he found himself wondering what the wound was at the heart—or in the mind—of man that kept him forever in exile from what he most desired.

—Lindsay Clarke, Parzival and the Stone from Heaven

For Whom the Buoy Tolls

Marsden Hartley: Lighthouse

Marsden Hartley: Lighthouse

For several months I’d had an email correspondence with Justin. We’d never met face to face. He was a poet who had also been a fisherman and spent time at sea. A mutual friend in the UK had initiated an electronic introduction based on our common interests. Subsequently we’d exchanged work by mail—copies of our respective memoirs and latest books of poetry. I had hoped my collection, Fishing on the Pole Star, would ring true for him.

We both grew up fishing for blues out of Sheepshead Bay and Montauk, I as a passenger on party boats, and he as crew. The account of his childhood, under the rigorous command of his father, a charter boat captain, haunted me. I was moved by the thought of him as a boy filling the ice chests, cleaning the catch, stowing gear and hosing the deck. What might he have been thinking as he untangled the lines of anglers fiddling with the drag, or gaffing a big blue before it jumped the hook? His formative years in my imagination tolled like the buoy I passed as a seaman, Robbins Light, at the entrance of New York Bay.

Justin’s emails to me were cool, almost formal, a few words to make a point or ask a question. Probing further in this medium after reading each other’s personal confessions on the page felt awkward. He had been born in Sag Harbor, a brilliant blue-eyed boy. He’d done well financially, and moved to the UK where he was now a citizen, with an office at Oxford of the kind reserved for scholars and Emeriti. I was surprised by his email in early April saying that he’d be spending the summer at his home, Ardetta Exilis, on Martha’s Vineyard, and would I care to visit him there on the weekend following my residency in August at the Gloucester Writers Center. I wrote back that my wife would be joining me in Gloucester and we had planned coincidentally to be in Vineyard Haven on Thursday where I’d be reading at the Bunch of Grapes bookstore. In a following message dated Friday, August 1st, Justin indicated that due to an unforeseen obligation, he was no longer free to host us for the entire weekend, but an overnight on Friday, the day after my reading, would work well for him. He apologized that it couldn’t be longer, but looked forward to our visit.

“Let’s do it,” said my wife.

.

Leaving Gloucester

On the my last night of my residency, Carol joins me in the one-room cape, perched on the road between Gloucester and Cape Anne. She may have expected something more elaborate. We sit at the small writing table I’ve been using all week, taking in the scene. With her broad cheeks, and full lips, red highlights in her shoulder length hair, she is my Queen of Cups. I point out the black and white photo of poet Vincent Ferrini, who had lived there, beside his friend, Charles Olson. Both have been palpable presences for me. Imposing at 6’7”, Olson’s physical size is proportional to his impact on American poetry. With good reason he named the persona that gave voice to his vision, Maximus. From the first night I spent there, lines from Olson’s visionary poem “The Kingfishers,” have been echoing in my dreams.

What does not change / is the will to change

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water

Carol points out that I’d come to this fishing village, inhabited the home of another poet/fisherman, friend of an even more renowned one, to read from Fishing on the Pole Star, my own poetry collection about fishing.

“It’s almost operatic,” she comments. “Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers.”

“I woke with these lines from ‘The Kingfishers’ in my head…then couldn’t stop thinking about Amfortas.”

“In Wagner’s Parsifal,” Carol comments. “Amfortas is a baritone wounded by his own holy spear.”

“Wolfram’s Amfortas betrays his duty as Grail keeper by killing another knight, who leaves him with a wound that won’t heal. His pain is almost unbearable. Only fishing eases it.”

“Until Parzival appears to heal him.”

“Or he’s able to get insured for a pre-existing condition,” I tease her.

“Parzival or Amfortas, which are you?” Carol’s green eyes sparkle.

I shrug. “Navigating between baritone and tenor.”

Earlier in the week I’d given a talk after my poetry reading. The title had come to me on the first morning here: Trolling with the Fisher King. Ideas and images followed. I recorded them in my dream journal. The thirty or so people who came to hear poems from Polestar remained when I followed up the reading with my talk. In fact, they seemed more engaged. What I had to say about the Fisher King spilled like water out of my Aquarian unconscious.

Operatic, indeed.

.

On the day of our departure, over coffee, I recall last night’s dream. I’m seated at a long table between Charles Olson and Vincent Ferrini, waiting for a scheduled event. They are talking about poetry and art, the essential nature of creative imagination with its spontaneous production of symbols. I lean over and say:

This is where we find ourselves

On soiled angels’ wings

This is the way we come to the end

The way the end comes to us

On soiled angels’ wings…

“What do you make of it?” Carol studies me.

Tarot (Alphonse) Mucha: Queen Of Cups

Tarot (Alphonse) Mucha: Queen Of Cups

“My discussion with them, and this place, is coming to an end. But why soiled angels’ wings?”

“Maybe that’s what happens when we try to fly beyond our comprehension.” She touches my hand. “Or sing off-key.”

I had embarked on my Fisher King troll with the encouragement of an imagined Vincent Ferrini gazing down at me from the black and white etching on the wall that made him look like Pedrolino.

“What if I can’t hold onto the Fisher King, the conversation I’ve been having with him all week? It could stop cold when I drive away from Ferrini’s house?”

“We can’t let that happen.”

Carol takes my arm as we walk to the Hyundai. As she sees it, my troll with the Fisher King is open-ended. We might think of our Martha’s Vineyard journey as a quest, and our mysterious destination, Ardetta Exilis, as the Grail Castle.

I slip easily into the driver’s seat.

Ardetta Exilis. My wife repeats the name. After fastening her seat belt, she checks her iPad. Carol is expert at searching the internet. Even before I pull out on to the road, she finds the definition: the Castle at the end of our road is named for the least bittern, a small wading bird similar to the heron.

.

In Flight

Wayne Atherton: Cover, Fishing on the Polestar

Wayne Atherton: Cover, Fishing on the Polestar

I point our silver Hyundai south, toward Boston. We will spend the night there on Kenmore Square, not far from what used to be Miles Standish Hall, the dormitory for Boston University students half a century ago. We arrive at the Buckminster Hotel, a grey stone and brick structure designed by Sanford White at the start of the last century. It follows the U-shaped corner of Beacon and Brookline in a circular embrace. What had been the front entrance is now a Pizzeria Uno, but in the 50s it had been the home of Storyville, that hosted Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Dave Brubeck, Charles Mingus and Sarah Vaughan among others. Many of them had performed here at the same time I lived across the street, before I knew their names.

The new entrance on Brookline is marble, with glass sliding doors leading into the original art-deco circular lobby, painted lemon yellow and crowned with gold-leaf laurels over the registration desk.

The space feels like the past renewed, still vital, reassuring but not cloying, open to what may come next.

In our case, a nap. And then a slow walk down Commonwealth Avenue like a European boulevard divided by a verdant mall. Falling light casts a glow over the stone and brick buildings with their turrets, garrets and wrought iron fences. We turn onto Mass Ave. and again on Boylston. The streets are full of tourists and natives, often distinguished by their respective body languages. Even the exuberant traveler betrays a certain stiffness.

On the veranda of the Atlantic Fish Company we are lucky to score a table by the rail hedged with flowerboxes and set with silverware on a white linen tablecloth. Carol and I split a toasted goat cheese salad of wild greens, roasted red and golden beets, spiced pecans, and red wine vinaigrette. She orders a seared north Atlantic salmon with ricotta gnocchi, Andouille sausage, spinach, heirloom cherry tomato and a white wine-lemon pan sauce. I can’t resist the seared sesame tuna served rare with sautéed bok choy. Half way through the meal we realize that only a year earlier this place was devastated by the Boston Marathon bombing. Which explains the pristine condition of the interior, the white walls and stair to a second tier, polished wooden floors and impeccable modern bar under a raised ceiling.

The wounds are no longer visible. I am less confident that they are entirely healed, that they do not bleed through, as unseen but cohesive as dark matter.

.

The afternoon is slightly overcast when we start out, follow US-1 down the coast, but burns off by the time we take Exit #7 towards Cape Cod. We cross the Bourne Bridge, and proceed to the second exit on the roundabout to MA-28, a flat highway divided by a median that will take us south to Woods Hole, where we will catch the ferry to Vineyard Haven. We stop in Falmouth at the bagel café, then continue down Woods Hole Road, then make a left to the Steam Ship Authority where we wait in a line of cars to be directed on to the ferry. We eventually follow directions to the belly of the vessel. Once parked, we climb three flights of stairs to the top deck. Summer residents and weekend tourists sit on hatches and lean against rails. Seagulls cry and the smell of salt air revives us from the fatigue that had nestled in my bones on the drive down.

The invitation to read at the Bunch of Grapes, the island’s only year-around book store, came through Jay and Ivy who shuttle between their house in Tisbury, and an apartment in Boston. Jay has spent the summer playing piano in a jazz duo at the country club, while Ivy owns and operates an art gallery exhibiting mostly local artists. They thought my Pole Star would attract an audience on an island populated by poets and fishermen, and offered to host us for the weekend. But when I told them about Justin’s invitation for the following night, Jay shrugged and agreed with Ivy that Justin was entirely unknown to them, as was the compound called Ardetta Exilis, in the area they referred to as Menemsha Heights. And when they greet us at the landing stage in Vineyard Haven, they confide that no one they’ve talked to has anything more to add.

I tell them that this is because the Fisher King’s castle occupies an imaginary space, a dimension that intersects with ours, but can’t be accessed by intention.

“Invitation only.”

.

The Bunch of Grapes is a legendary bookstore on the island, catering to a literary population, among them a couple of visiting U.S. Presidents. Located on Main Street in Vineyard Haven, it occupies a space across the street from the original store that burned down in 2008 when the restaurant next door, Moxies, went up in a kitchen fire. The new location, once a Bowl & Board, is now hedged by wooden book cases and table displays behind lattice windows. Prominently on display are signed copies of Boys in the Trees by local author Carly Simon. And another island resident, historian David McCullough, has left a supply of his latest book, The Wright Brothers.

I am here to read from Fishing on the Polestar. Our event takes place in a nook at the rear where chairs and a couch have been arranged in a circle. There may be as many as thirty people gathered and we need more chairs. As we suspected, the subject of fishing appears to have expanded the audience.

Richard Saba: Ancient Clamor

Richard Saba: Ancient Clamor

Most of those here understand how to read the book-of-the-world in birds and schooling fish, weed-lines and tides, and an invisible bottom. These fishermen, both commercial and sport, are intent on blues, stripers and bonito. But I talk about small islands, some uninhabited, or protected by reefs, and I enumerate the rituals of trolling baits and lures on multiple lines that shape the pursuit of marlin, the fisherman’s Grail, through the Bahamas. The focus of everyone in the room coalesces when I reach the poem at the heart of this collection, “Marlin Strike.”

It opens when a five-hundred pound marlin takes the hook, and a life and death communication between fish and fisherman transpires through a strip of mono-filament. The powerful creature dances, leaps, tail-walks the water until it is exhausted and comes willingly to our starboard side where the “wire man”, hand wrapped carefully around the wire leader, “swims” the fish until his color returns. A marlin with faded pigment is instantly a feast for sharks. At full strength, the marlin is shark-proof.

I describe how Caleb, our wire man, holds the creature close to our hull, talks softly, strokes his bill. The boat cruising at a super slow speed allows water to circulate through the gills. Caleb swims him until we see the marlin’s deep purple and green stripes glow, then removes the hook. The marlin, whose jaws are capable of crushing a human hand, gently bites down twice on Caleb’s to indicate he is ready to go. Caleb releases him. Still brushing our gunwale, this great creature rises above it, remains suspended for a timeless moment:

we gaze into

the perfect roundness of his eye

……………….watch the boundary

…………………….between us

………………………dissolve

……………….glimpse

in that great wink of eternity

………..the Divine Child

……….watch him swim

……………..away

………..the unconscious

………….conscious of

……………..itself

When I‘ve finished, people linger for Q & A. The blonde woman who had been working the register when I came in, wants to know more about what I saw in the depths of that perfectly round eye. The question brings tears to mine. I have a hard time describing that gaze, so deeply knowing. Except to say that it continues to gaze at me, locates me in my own depths, a primordial moment that endures as an inexpressible word on the ocean’s tongue.

And then, to release the catch? Inconceivable for most, especially for those who troll the waters around this island.

“There’s no choice, if you truly recognize the intelligence you’re dealing with.”

“Is it hard to release it, watch it swim away?” a thin young man with a piratical blue do-rag tied around his head wants to know.

“How do you say goodbye to one who takes a part of you with them?”

A greybeard in a watch cap, about my age, comments on my image of Vietnamese fishermen in dugouts pulling up silver splinters of light on multiple hooks. He has seen them too, on the South China Sea, and appears comforted by the memory.

An elderly women in L.L. Bean jacket lets me know she is well into her eighties and regularly fishes from her dingy in Katama Bay.

.

Good Directions

John Marin: Marin Island

John Marin: Marin Island

I remember that in the tale, Parzival is told by a man fishing from the back of a boat that he can find shelter in a castle not far away. But he must follow the fisherman’s directions, proceed up the road, make a left, and then cross a drawbridge. Parzival is unaware that this is the Fisher King himself guiding him to the Grail Castle, or that in symbolic terms the left is the direction of the unconscious, the side sinister.

The road is flat, lined intermittently by low stone walls framing oak, and white pine hedged by meadows and wetlands. We wind through Tisbury, and Chilmark, past an untended graveyard where John Belushi is buried. A mile beyond that landmark we find Menemsha Road, make a right, snake up hill, admiring private homes tucked into the hills. Night Heron Lane, a name that foreshadows the least bittern, comes up quickly. We turn left, and continue climbing. Soon Carol points to the unsigned road on our right, thickly wooded and flanked by huckleberry, bayberry and the occasional white oak saplings. We have followed the directions faithfully.

“This must be it,” Carol’s voice is hushed “The entrance to Ardetta Exilis.”

I steer the silver Hyundai between imposing stone pillars eight feet high on to a graded gravel road that curves gently up a wooded slope. We level off past a grassy alcove hedged by rhododendrons on my side, before opening on Carol’s side into an informal Japanese garden, featuring a pond surrounded by weeping maples. This careful balance of art and nature announces a domain created by a precise and prosperous hand.

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Eclipse

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Eclipse

I stop a few feet from a structure resembling a Mayan stele or Egyptian boundary marker planted in the ground where the road loops right into unseen territory. We get out of the car and walk over. This stele is made of a polymer material that might be mistaken for translucent marble. There are words engraved on it, which turns out to be a poem. In two four line stanzas the poet asks us to consider which is most frightening, an indifferent or hostile universe.

“One of his,” I tell her.

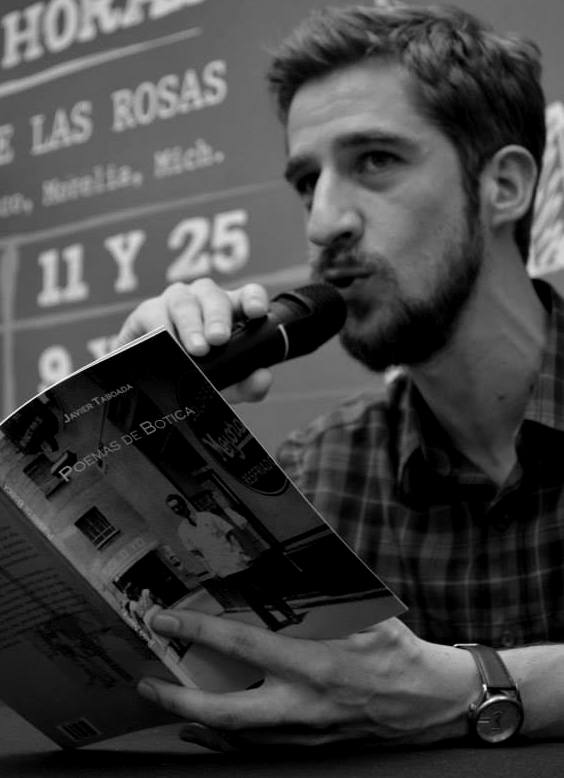

The mutual friend who had introduced us thought that Justin and I, two fishermen/poets, might have something to say to each other. This had prompted an exchange of books, along with a few brief emails. I’d been touched by the unornamented severity of his memoir. But the same quality in Justin’s poems left me unmoved, indifferent rather than dismissive. Whatever we might have to say to each other had not seemed pressing as I read his writings. But now, having entered his world, I’m curious.

“Do we abandon all hope?” My wife strays to the edge of the Japanese garden.

“Not yet.”

I follow her to a bench beneath the weeping cherry tree. We sit. Neither of us know what to expect, but I fill her in as best I can, starting with details I recall from his memoir.

Justin was born to an Irish mother from Hell’s Kitchen on the upper West Side. The family had owned a bucket-of-blood bar on Broadway. Her brother, an avid fisherman, and a Westie, had taken a bullet in a gang related incident. She met her future husband at her brother’s wake, the Captain of a charter boat out of Montauk. After they married, she moved to Sag Harbor, and never went back. Her only child, Justin, grew up a working class Bonacker, or “bub”, tags most island locals wore with pride. Justin never identified with either. There are photos of him as a wiry boy with curly locks, his jaw set as befits one under his father’s thumb. He is alone in each of the black and white photos, one taken beside a bicycle, the other in front of the boat. Justin excelled at school, but otherwise spent his time securing lines, gutting fish, and cleaning up after rich customers—until he escaped on scholarship to Harvard, graduate work at Oxford, and then to a career in international finance. Evidence would indicate success.

Herman Maril: Province Town

Herman Maril: Province Town

It’s a long way from a peninsula at the tip of Long Island’s south fork to this gardens in the Menemsha Hills. Hands that once dispensed chum, the smelly stew of fish parts, bones and blood thrown into the water as bait, now held a British passport and the key to rooms at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he spent at least half of his year. He also has an apartment in London’s elegant Palace Gate. This house in the Vineyard may be as close as he gets to his blue-collar Bonacker roots at the end of Long Island.

While I often fished out of Montauk on party boats, the pricey charters were always financially out of my childhood reach. It’s just possible though that Justin and I crossed paths as teenagers on the dock. I’ve spent enough time in that world to imagine what it was like to grow up as he did, and why he felt compelled to escape it.

Less familiar, is the world in which he now lives.

.

Be Welcome Here

We continue up the drive to a parking area in front of a circular blue stone terrace where a weathered woman in denim coveralls, her silver hair piled on her head, waves us into a parking space. Her dark eyes are wide set above broad cheeks. It’s hard to judge her age, but it is north of forty. She welcomes us to Ardetta Exilis.

“Did you have trouble finding us? First timers often do.”

“It feels like a separate world,” observes Carol.

“What’s left of our ancestral lands.”

Djorde Ozbolt: Monkey Business

Djorde Ozbolt: Monkey Business

She is quick to let us know that she’s a full blooded Wampanoag, who traces her line back to the great chief Massasoit. Even with her coiled silver hair, and in work clothes, she radiates dignity. I think of her as “princess.” She helps us carry our backpacks and carry bags up a hill that flattens into a field bounded at one end by a forest. Through a gap in the vegetation she points out a view of the Aquinnah cliffs. We follow her to the guest cottage, a grey cape perched on a raised deck that offers a view of the ocean trough a tangle of windswept pines.

“This is the highest point on the island,” she tells us. “Over three-hundred feet.”

Our princess opens the sliding glass door, then invites us to enter. In spite of the rustic exterior, the appointments inside include brass bathroom fixtures, comforters stuffed with the finest down, and flower arrangements flanking silver trays of dried fruits and trail mix. Our princess waits for us to take it all in, before instructing us to feel free to explore the grounds or rest, but that we will be dining tonight with our host. The path at the far side of the meadow follows the ocean and leads eventually to the Main House.

We’re expected there at 8:00 PM.

“Please,” she adds before taking her leave, “try to be on time.”

.

In the Zone

We start out early. The path runs through a forest of Bonsai pines, their limbs artfully twisted by strong winds. Beyond it, parallel rows of solar foot-lights are reminiscent of a miniature landing strip. Their glow lines a gravel path across a lawn that slopes to a ridge on the right. We walk to the edge, where a rocky slope drops to a beach sixty feet below carpeted with smooth round stones. The light appears to be falling fast. S/W of us clay-faced bluffs burn red in the last rays of the sun. Los ultimos rayos del sol.

Arthur Dove: Red Sunset

Arthur Dove: Red Sunset

Carol points to a steep descent along a trail flanked by huckleberry, and bayberry. On the west side of the slope white oak saplings flank the trail to a look out, and from there a cedar and fir stairway descends to the beach. Small waves break soundlessly. A red-tailed hawk circles above them. Carol would like to go down there, feel the spray.

I touch my watch. No time for a detour. But she holds my arm, and we linger there, details in a painting where light spills over the bluffs like blood from the wound in a darkening sky. Before the sun disappears, we break the spell and head back to the path edged by dwarf conifers. Solar lights glow like fireflies that lead us to a pond, where they end at a wooden foot bridge. Just beyond the bridge, a blue stone patio borders the two story structure of stone, wood and glass at the crest of the hill. It is a hybrid of modernist and Romanesque forms. A wall of tinted glass rests on a fortress of weathered grey shingles incorporating cathedral windows and an entrance set into a gothic arch.

“Ardetta Exiles,” whispers Carol.

Our shared but unspoken sense of the occasion is now clear: what started off as a trip has turned into a pilgrimage. Two stone benches on the patio convey the peacefulness of a medieval monastery. Carved oak doors rise the full height of their gothic niche. It is clear that beyond the entrance, the walls disappear behind a wall of arbor vitae to occupy considerably more space than meets the eye.

“It’s an eyrie,” I reply.

“I agree,” Carol squeezes my hand. “Very eerie.”

“Not that,” I clarify. “Ardetta Exiles, the bittern’s nest.”

Percival’s Quest, 1385-1390

Percival’s Quest, 1385-1390

A carved wooden door set into the niche rises to a vaulted ceiling. Strips of glass on either side of the door allows a peek into the ante-chamber. I can’t find a bell, so reach for the brass knocker shaped like an eagle’s claw. Before I can bring it down, a shape appears on the other side of the glass.

The man who opens the door wears a navy cashmere crew neck over white ducks and boat shoes. I barely recognize him from the black and white photos in his memoir. Justin’s once curly locks have thinned, spun gold turned reddish and threaded with grey. He bows slightly, then stands back to let us in. As I wonder if he is permanently bent like a question mark, he straightens to his full height, I guess at 6’3” or thereabouts.

“I believe we’re on time.” I enter, Carol close behind me.

“Perfect.” His voice is soft, almost apologetic. “Forgive me. We keep only a small staff, so I must answer the door myself. Come in.”

Frank Auerbach: Head of E.O.W. (1955)

Frank Auerbach: Head of E.O.W. (1955)

Justin’s head appears too small for his body, but his clean shaven face, curiously unlined except for grooves bracketing his mouth, makes his age impossible to judge. The most striking features are his blue-grey eyes. They catch mine like fish hooks, then release me.

“Please.”

Justin takes our jackets and folds them neatly on the bench to his right. His long-fingered hands are tapered, almost delicate, in contrast to his corded neck common to certain thin men whose muscles are like cables. His shoulders are slightly bent in the manner of one who must gaze down at others. When he leads us into the vestibule, he appears off balance, as if one leg were a millimeter shorter than the other. A skylight in the entry way illuminates an abstract painting. Justin draws our attention to it.

“de Kooning,” I guess, thinking it one of the Untitled series he painted in the 70s.

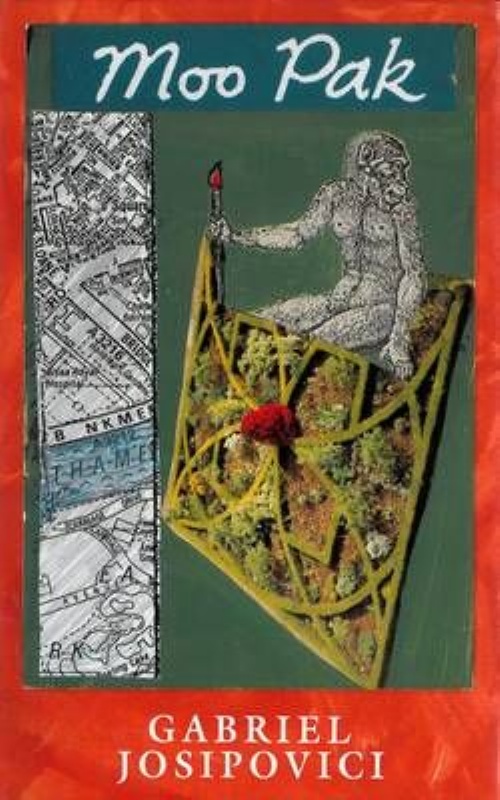

“Auerbach,” Justin corrects me. “Our greatest living painter.”

A few steps beyond we stop in front of a cubist assemblage on a pedestal. It stands at the arched entrance to a dimly lit room. Steel straps wrap a green vertical chess board. I could picture it in a garden by a wading pool, a New Age sundial.

“David Smith?”

“No,” Justin gentles my ignorance. “It’s a Caro. Chamber Music. If you listen closely, it sings.”

“Caro nome…” says my wife.

“Ah, you know Rigoletto.” Justin’s face lights up for a moment, then becomes stern. “I mean Anthony Caro. The music his sculpture makes isn’t an aria, from the heart, but structural, detached, like the vibration NASA captures in the planetary rings, Uranian music.”

“I don’t believe I’ve ever hear such music,” Carol is thoughtful

Justin steeples his fingers in front of his lips. He takes her in.

“Keats tells us, unheard music is the sweetest,” I observe.

Justin is less impressed with me. He takes Carol’s arm. She steps closer to the assemblage. “Bend closer.”

“Ah, I hear it,” she says, rising after moments of fixed attention. “The whispered song in a chambered nautilus.”

“Indeed.” He lets go of her arm, and, as if to balance the moment, addresses me. “Caro made this piece in the 60s. I found it in his studio shortly before his death last year at eighty-nine.”

We cross the threshold into the next room, which is also dimly lit. On the far side I can see a picture windows framing the night sky. When he turns up the lights, the world bursts into color. Paintings of all descriptions float on white walls, luminous as reef fish. Glazed ceramics, dyed weavings and metal sculptures glow on shelves and in niches like shards of the spectrum. Carol and I are stunned.

Kenneth Armitage: People in the Wind

Kenneth Armitage: People in the Wind

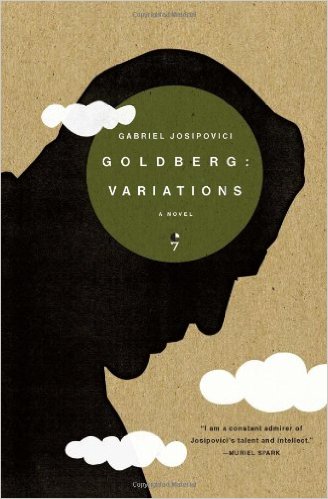

A monumental Anselm Kiefer dominates one wall with its mottled surface, lattices of blacks and golds floating like clouds in a white and blue sky above a field of wild flowers, and mountains on the horizon. Running through the sculptural topography of ridges and charged particles there is the suggestion of train tracks in the field. I think they must lead to Auschwitz.

“Jerusalem,” he all but sighs. “This way.”

Justin leads through an arch on the other side of the painting, but cautions us to be careful. There are three steps leading down into the dining room. As he takes the steps I note again his slight but definite limp. He walks to the head of a table surrounded by cathedral-back chairs. The space can seat twelve comfortably. Tonight it is set for four. He pulls out the chair on his right for Carol, then indicates the one to his left for me. The fourth place at the other end remains empty. Each place is set with delft china and Waterford crystal. Wild flowers—violets, dog roses, primrose, black eyed-Susan, orange cornflower, red trillium, buttercup and purple phlox decorate the center.

I’m comforted by Carol’s smile facing me across the table, then direct my attention to what is on the wall behind her. A rectangular canvas in a plain metal frame features a beefy young woman, dark hair pinned back, in a white satin sleeveless dress and toe-shoe on her one exposed foot. Her other leg folded under her, she sits on a chair with her left arm plunged into a long black boot which she polishes with the cloth in her other hand, back to a window in the stone wall. What’s most remarkable about this work is the way moonlight floods the room with shadows, at the edge of which a cat stands on two legs looking up at the sky. I see elements of Balthus, and Magritte, but know it’s neither of them.

Paula Rego: Angel

Paula Rego: Angel

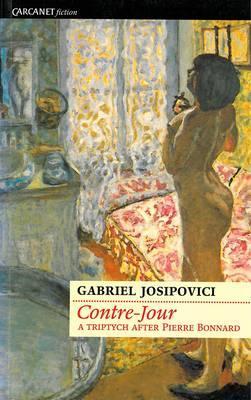

“Latin American.” I guess. “Botero?”

“Nice try.” His frown lines deepen when he smiles. “Paula Rego. The Policeman’s Daughter.”

Paula Rego: House Underground

Paula Rego: House Underground

Rego, he tells us, is Portuguese, though she’s long been a resident of the UK. We learn that she is highly respected in the English art world, and has been honored by the Queen. Justin knows Dame Paula, has spent time at her studio. He describes her work as darkly childlike, dominated by grotesque fairytale figures in narratives that hint at sexual secrets. This one, between father and daughter.

A tall, expensively preserved woman in her fifties interrupts our host when she enters from the kitchen behind me. She has salt and pepper hair cut boyishly close. Her pale face defined by “good bones,” is webbed with fine lines, but tight skin around her mouth and jaw hint at cosmetic surgery. Makeup, skillfully applied, heightens the color in her cheeks and lips. A white cardigan over designer jeans relieves the formality of her presentation without cheapening it. Her voice is soft, and slightly accented.

“Good evening. So glad you could come.”

“This is Violette, my fourth wife.” Justin rises briefly.

“I hope you’re not vegetarians.” Her voice betrays a hint of an accent. She shakes our hands before taking a seat facing her husband at the other end.

“Violette is French, more precisely, Parisian.”

“I wouldn’t have guessed,” Carol told her.

“All those years at the American School,” Violette replied.

“And at Cornell,” commented her husband. “She’s a vet.”

“Large animals. Mostly horses,” his wife pours claret from a crystal decanter beside her husband, then moves to her seat at the opposite end of the table.

“There will be a warm port later, to wash down the daube, which Violette has prepared.”

“I hope you like daube,” she says.

“We had a memorable daube several years ago in Normandy,” I tell her.

“I think of it as a variation on beef stew,” Justin toasts. “Bon appetit.”

Carol observes that Justin seems to know most of the painters on display here personally.

“He makes a point of it,” his wife replies. Violette rings the bell at her end.

Our princess, the Wampanoag woman who greeted us this afternoon emerges from the kitchen, followed by a man who might be her husband carrying a silver tureen: the daube has arrived. They are both dressed in white shirts and black pants, familiar servers’ colors. The man places the tureen in front of our host, besides a stack of porcelain bowls. The smell of vegetables and meat well-seasoned with herbes de Provence increases when Justin removes the lid.

Deliberately, as if he’s peeling skin from a grape, Justin serves dinner.

I ask him about Anselm Kiefer, a favorite artist of ours. Kiefer’s breathtaking Let the Earth Open and Bring Forth a Savior, has drawn us again and again to MASS MoCA, the museum in N. Adams Mass., since 2008. Justin shakes his head sadly. Kiefer has become complacent, he says. Paula Rego continues working despite health issues. Frank Auerbach, he repeats, remains the great genius of our time. At eighty-five he is as productive as ever, and uninterested in the marketplace even though his work increases exponentially in value by the day.

Anselm Kiefer: Let the Earth Be Opened and Send Forth a Savior

Anselm Kiefer: Let the Earth Be Opened and Send Forth a Savior

“The marketplace has been good to you,” I observe.

“People I do business with know me well.” He fixes me with translucent blue eyes, then smiles ever so slightly. “As we speak, I’m in the process of letting go of a company I built years ago to create a new one. I do it with minimal stress.”

“Almost casually?”

“Exactly.” He rolls past any suggestion of irony. “My great love, beside art, is the sea.”

“One we share,” I remark.

Justin is quick to let me know that here, too, I’m out of my depth. He has crossed the Atlantic in small crafts three times—most recently on the 38 footer. The earlier ocean crossings he made with other men. He will make the next one alone.

“I’m sailing my boat to Naushon Island tomorrow morning. Five miles to the North Shore in Buzzards Bay.”

“Sounds like a good life,” I observe.

“Not without its challenges.” His voice softens.

I agree. No life is free of difficulties.

“He’s referring to his son and third wife.” Wife number four gossips openly. “Others in his family, also, who will go unnamed.”

“Many depend on me. And I take care of them all.” His tone changes from confession to something harder edged. “I care for them, but not about them.”

“Really?” Carol is piqued.

“I don’t get emotionally involved.”

Justin declares as a point of pride that he doesn’t trust emotion, which includes love, vows of all kinds, gratitude, and promises. His jaw and neck tighten visibly, then release.

“What do you trust?” Carol asks him.

“One thing only: the human need for protection. I’m willing to provide this for others, according to my code. After I’m gone, that ends.”

“What do you mean?” my wife leans forward.

Francis Bacon: Lucien Freud

Francis Bacon: Lucien Freud

“Tell them,” Violette’s frown lines deepen. When he hesitates, she continues: “He’s leaving all his wealth, including his art, to charity—nothing to his son who has not lived up to his expectations.”

“It must be difficult to live up to the expectations of one who has accomplished so much,” I keep my tone neutral.

“That’s true. Children of men like me don’t fare well.”

Justin’s tone is flat, but something flickers in his eyes. For a second I glimpse the wounded bait boy from Montauk with the hands of an artist, one who spent his childhood cleaning other people’s fish. I wonder if we passed each other on the dock as kids, and if we had, would I have noticed, or remembered him?

Violette rings the bell.

Her minions are almost invisible in their ministrations. The man whom I guess to be a Wampanoag too, clears the table, then helps the princess bring in individually built dishes of fruit compote. Our host becomes animated again and pours four snifters of deep red port to go with the dessert. He then turn his attention to Carol.

“And you, who know the words to Caro nome…?”

“I’m a private voice teacher.” She sings a few words from Gilda’s aria in Rigoletto.

Justin becomes visibly intrigued. He probes further, listens attentively to Carol talk about her training, and early career as an operatic soprano. She has performed with the original Wolf Trap Company, in the Bernstein Mass, sung with the Philadelphia Symphony, but at one point found a professional career too stressful to pursue. Instead, she has taught music in the public schools until her retirement five years ago.

“I have my own voice studio, and work with a few aspiring performers, but mostly young people involved with theater. I find it very rewarding.”

Dragon King

Dragon King

Justin nods, then inclines his head as if hearing something inaudible to the rest of us, and then, in a light, but not unmusical baritone, sings:

La ci darem la mano,

La mi dirai di si,

Vedi, non e lontano,

Partiam, ben mio, da qui.

Carol hardly notices he is touching her hand, and responds in her haunting soprano:

Vorrei e non vorrei,

Mi trema un poco il cor.

Felice, e ver, sarei,

Ma puo burlarmi ancor.

“Mozart. Don Giovanni,” says Justin.

“Don Giovani attempts to seduce Zerlina,” Carol explains. “La ci darem la mano, ‘We will take each other’s hands.’”

“My favorite duet,” he says, then half-sings the words. “’Andiam, andiam…come, come with me and reawaken the pleasure of innocent love.’”

“But Elvira, whom he has already seduced, interrupts him.” It is Carol, in this case, who interrupts our host.

Justin’s long fingers linger on her wrist, before he withdraws them. But not his gaze.

“It doesn’t end well for the Don,” my wife continues. “In the end he refuses to repent and a chorus of demons take him down to hell.”

“The poor baritone is undone.” Justin apologizes. “As you can see, beside art and fishing, my other great passion is opera.”

“I thought you didn’t trust emotion?” Carol reminds him.

“Except in opera,” comments Violette.

“I’m not at all sentimental.” Justin glances at his current wife, then turns his attention back to mine. “But I have powerful desires.”

“My very own Don Giovanni,” Violette’s voice falls to a whisper. “And he, too, is unrepentant.”

His jaw tightens again. This time, it doesn’t release. In that bait-boy voice, his eyes still fixed on Carol, he confesses to being a great philanderer.

“It’s the only thing I learned from my father, besides how to fish and captain a boat.”

“I’m sorry about that,” Carol’s voice breaks. She is genuinely moved.

“A question for you.” I intervene, attempting to mask my chagrin.

“All right.” Reluctantly, he turns toward me.

“Do you consider your impact on others?”

“What do you mean?”

“Your entire presentation from the moment we walked in has been a demonstration of your power. And now you sing the part of Don Giovanni gazing at my wife as if you’re about to invoke the Droit de seigneur.”

Justin appears surprised to hear this stated so boldly. He at first steadies himself as if to fend off an insult, but recovers in seconds. A smile crosses his face.

“Of course,” he replies. “You could read it that way.”

Intending to disarm him and to touch the core of his wound, I ask: “Was it hard to meet your father’s expectations?”

Justin takes a deep breath, then nods. “I forgot, you’re a psychotherapist.” His voice is almost raw. “I did everything he asked of me on the boat. I was cook, mate, rigger, and fisherman. My father thought that everything else had little value, including my wealth, art, or intellectual achievement.

What you see here, my ‘presentation’ as you put it, would have meant nothing to him.”

I suspect that his father’s rejection of what the world now considers his son’s accomplishments, utterly devalues them for Justin. Without a doubt, my question has pierced through, but instead of healing his wound, has opened it up. I realize that I wielded my challenge like a sword, as Amfortas did when he betrayed the Grail.

I recall Parzival’s question. The one he failed to ask which now perches on the edge of my tongue: What ails thee?

But I can’t get it out.

Try as I may to manage my response, his defenses have triggered my aggression rather than my compassion. Although ashamed, I am defiant. I’m also more aware than Parzival was on his first visit, and this changes everything.

What ails thee?

Would Justin find the question naïve? Whatever I surmise about his condition, he is surrounded by abundance and gives from it what he deems necessary to those he must, and those he favors.

All else is post mortem.

After coffee and fresh fruit compote, I am ready to leave. I fold my napkin and place it beside the empty crystal. Carol follows suit. As I stand, and as my wife pushes back her chair, a hint of panic flushes his cheeks.

“Au revoir,” says Violette. “I’m going riding in the morning and probably won’t have a chance to see you.”

We exchange European ghost kisses with wife number four, and prepare to leave.

“A few more minutes of your time, please.” Justin faces us. “I know you’re tired. It won’t take long. There’s something I want to show you.”

.

Paula Rego: Vanitas (pastel, 2006)

Paula Rego: Vanitas (pastel, 2006)

There is a new note in his voice, a compelling urgency. Violette and the princess have already started clearing the table. Our host indicates that we should turn right, to another wing of the house. We follow him through corridors displaying art work by blue chip painters, sculptors and ceramicists, to a landing where we stand at the rail of a balcony that looks down at a floor below. Justin points to the spiral staircase a few feet away. We descend single file down into the belly of the castle. I’m reminded of the unrepentant Don Giovanni sinking into hell surrounded by a chorus of demons and I half-fear what we might find—a dungeon outfitted with leather whips and electronic sex-toys for practices not inconsistent with the humiliation he experienced as a child.

But I am wrong.

Justin wants to show us his secret place. It is dimly lit, without windows or mirrors. This is his temenos, a sanctuary where he feels safe and, perhaps, even whole.

The space resembles a cathedral—not through any architectural intention, but in the almost shrine-like arrangement of contents beneath a vaulted ceiling. State-of-the-art Bose speakers like icons rise from perches on the walls. Amplifiers, monitors and support equipment all have their own niches. At the center of the room, elevated a foot above the floor on a wooden platform, a black leather chair with a headrest waits with open arms. A headset and a remote rest on end tables on either side.

It is a throne.

Carol and I have been given an audience, are the audience, in this throne room surrounded by invisible courtiers— tenors, baritones, sopranos and mezzos. CDs and vinyl, arranged on tiers of shelves like rungs on a heavenly ladder no doubt hold a peerless collection of music, especially opera. The throne is placed optimally for balanced sound. It can swivel, or be adjusted for comfort at any in angle of repose.

Robert Fludd: Temple of Music

Robert Fludd: Temple of Music

Of all his worldly possessions, the ones in this chamber are not for display. Everything here, he confides, exists for him alone. He has felt compelled to bring us here thanks to Carol. In spite of his protestations, her response to his sculpture with Caro nome, and in the duet La ci darem la mano… her Zerlina to his Don Giovanni has opened Justin’s heart. And then I, too, have pierced it with my question. Even if I haven’t fully understood how, I have penetrated his the shield of his wealth, his palace of defenses to realize his struggle all along has been with the Charter Boat Captain, the philandering father, who saw in his son only what he despised in himself.

And I grasp that it’s a wound we share. How else could I have seen it in him, if it weren’t mine as well!

“I am happiest when I come here,” he tells us. “I don’t need anything or anyone else. And I am never lonely. Let the world do what the world does, as long as I can sit in that chair and listen to Maria Callas.”

Quickly, Justin selects a record from a shelf, sets it on the turntable, adjusts the earphones, and then ascends the throne. He picks up the remote, locates the cut he is looking for, then clicks it. At that moment, his eyes close, his head falls back, rests on the chair, then jerks forward and twists, like the torsos of Michelangelo’s prisoners struggling to liberate their still imprisoned bodies from uncarved marble. He clicks the remote and the voice of Maria Callas fills the room with Tosca’s lament, Vissi d’arte.

His features compress, then release from what appeared an unbearable moment of agony. And then I see his cheek is wet, but without a trace of tears.

.

Reeling In

John Marin: Sunset, Casco Bay

John Marin: Sunset, Casco Bay

We are packed and ready to leave Ardetta Exiles a few minutes after 7:00 AM. Only the conifers stir in a sea breeze. We walk from the guest quarters to the main house hoping to thank our host and say goodbye. No one answers my claw-hammer knock at the door. Justin told us that he’d be leaving early to catch the tide on his trip to the privately owned Naushon Island, where only invited guests are allowed access. Violette, his fourth wife, let us know she had plans to go riding in the morning, and said her good-bye after dessert. She keeps a horse at a stable nearby, where one of her companions, a former Olympic dressage competitor, often accompanies her.

“I wish we could’ve talked more,” says Carol. “She reminds me of Don Giovanni’s spurned lover, Elvira.”

“How does it end for her?”

“She enters a convent. But before that, Elvira gets to sing a great angry aria.”

Back in the parking lot, we search for the princess. This descendent of Massasoit exhibited the rare balance and wisdom of natural royalty, even as she served and cleared someone else’s table. I’d hoped to thank her for making us feel at home, but neither she nor her male companion are in evidence.

Belted into our Hyundai, we start back down the road along which we arrived the day before. In the stillness that accompanies our departure I feel like Parzival leaving the Grail Castle, haunted by the specter of missed opportunity.

Peter Reginato: Yellow Interior

Peter Reginato: Yellow Interior

Justin protests that his solitude is sufficient. It doesn’t matter if anybody sees what hangs on his walls or hears what he hears in the depths of his castle. For all of his material abundance, cultivated esthetic, imperial assumptions, he remains Amfortas. The voice of his suffering continues unheard in its own operatic frequency.

“Why are you frowning?” asks Carol.

“Not sure.”

Again, I’m seized by a sense of personal failure. I’d missed the point of the dinner at Ardetta Exiles, and the challenge posed by my host. It was easy to look into Justin’s face and see his wounded pride, but not my own. Instead of resonating to his buried grief, I’d fed my envy.

“Have you figured it out?” my wife pursues.

“The name Parzival means ‘to pierce, to break though’. I ruffled his defenses, but failed to breach them.”

“Or you own” she says.

We drive past the default question our host has graved in polymer: What frightens us most, the indifference or hostility of the universe?

Beyond the stone pillars, we turn onto the road that will lead us back to the ferry from Vineyard Haven to Woods Hole.

“What’s to become of Justin?” I ask aloud.

“You tell me.”

“What if the Fisher King were to disappear completely, or become like the neutrino, a particle that leaves no footprint but binds the world?”

My wife smiles. “Would that change what’s in your heart?”

Kusama: The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away

Kusama: The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away

(light installation at the Tate Modern)

I glance up into the rearview mirror. As I do so, an image appears in another mirror at the back of my head where a moment ago there had been neither image nor mirror. The unhealed Fisher King, crowned by earphones, listening to Maria Callas sing—not Gilda from Rigoletto, or Zerlina from Don Giovanni—but an aria by Puccini. The shock of her voice pouring from those Bose speakers, filling the room with Tosca’s lament when she fears that her God has abandoned her. It begins:

Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore

I lived for art, I lived for love

And ends:

Perchem, perche, Signor

Ah, perche me ne rimuneri cosi?

Why, why Lord

Do you repay me like this?

And this is what I’m left with, the image of Justin on his throne. Long after it dissolved, I can feel the aftershock of his unbearable pain and invisible tears.

.

Dancing in the End Zone

Wayne Atherton: Everything Is Permitted (collage)

Wayne Atherton: Everything Is Permitted (collage)

We feast on clam chowder in the open air on the ferry’s top deck. Later, as we cross Buzzard’s Bay on the Bourne Bridge, it is comforting to drive in silence, each of us attending the theaters of our discrete minds. After a long straight drive on the Mass Pike we pass into New York State. After so much time in New England it looks unkempt. This is abundantly evident as we approach Albany on the other side of the Hudson. The State Capital is a bizarre assemblage of architectural periods conjuring the archeological remains of an incoherent civilization: Rockefeller’s modernist Empire State Plaza with its three phallic white tombstones and the other worldly entertainment center, The Egg, nested at its center, mingle with 19th Century row houses, beside Gothic and multi-arched Romanesque revival buildings like the State Capital.

“Home again,” I observe.

“Are you ready for re-entry?”

“I’m working on it.”

It occurs to me that in our time the Fisher King might exist not as a figure to be healed, but one who wakes us to ourselves by remaining unhealed. A post-modern Parzival’s attempt to heal him must fail. When I share this with her, she points out that I did affect Justin with my question, even if I’d asked it in anger.

“The attempt may fail, but not the longing to heal. In spite of your anger, you wanted to get through to him.”

“Personally, I’m looking forward to poached salmon, and a glass of wine.” I yawn. “Then early to bed.”

“If you’re tired, I can drive.” she says.

“We’ll open a bottle of Breca,” I tell her. It’s our favorite Spanish red.

We turn right at Albany on the elevated highway that crosses the Hudson to 787 North along the river to Troy. We take this as far as the exit to 7 East towards Saratoga. I reconsider Parzival’s question, what ails thee or me? The answer, I conclude, is numbness.

Roy Laewetz: Three Fishing Ladies (detail)

Roy Laewetz: Three Fishing Ladies (detail)

I search for the mystery once evoked by the image of a fisherman in the mist on the stern of a skiff. I am having difficulty feeling anything that expresses the awe and fascination once posed by The Wounded Fisher King.

“Stay to the right,” my wife directs me. “We turn off here.”

“I see it.”

“What are you feeling?” asks Carol.

“Lost,” I tell her.

.

I’m careful to negotiate the next turn that arcs right, then twists left to 87 North without a hitch. After merging on to the Adirondack Northway, I adjust the Cruise Control to the 75 mph that is consistent with the flow of traffic.

“Let’s stop at the Price Chopper,” says Carol. “I think we need salad, vegetables, and maybe a baguette.”

“Is it conceivable that in the course of time Amfortas might have become so disconnected and that he turns into Justin?”

“And if your wound went unaddressed for ten centuries?”

“You were right from the start,” I admit. “This only makes sense if Parzival and Amfortas are two split off parts of a single psyche.”

Albrecht Durer: Melancolia I (detail)

Albrecht Durer: Melancolia I (detail)

We get off the Northway at Exit #18. A few minutes later we pull into our driveway in front of the white ranch at 55 Garfield Street in Glens Falls, NY, home of Bob & Ray’s “Slow Talkers of America”. I take comfort in this, and the “quantum uncertainty” in which a particle can exist everywhere and nowhere, until consciousness connects subject to object and we see as we are seen. Carol removes her backpack from the trunk, and hands me mine.

Paula Rego: Dame with a Goat’s Foot

Paula Rego: Dame with a Goat’s Foot

“It’s good to be home,” says my Queen of Cups, as she takes my arm with her free hand on our way to the door.

.

In Search of the World Soul: An Afterword

If life is to be sustained hope must remain,

even where confidence is wounded,

and trust impaired.”

—Erik Erikson

.

By all accounts, in his early years, Carl Jung was terrified at the prospect of being so internally split that he would forever suffer from a psychic Amfortas wound. Later, in 1959, during a BBC interview, in response to the idea that collective dissociation would at some point reach a critical mass, Jung observed: You know, man doesn’t stand forever his nullification.

Darren Tunnicliff: Quantum Entanglement through Time

Darren Tunnicliff: Quantum Entanglement through Time

Jung pointed out that the latent intelligence of the deep psyche, what we call the unconscious, responds to painful conflicts under pressure, over time, with the dreams and symbols that help us to understand them. The Grail is such a symbol. It arose from the growing disconnection between Eros and agape, the elevation of spirit in a devalued physical world. Wolfram’s Parzival tells us that the Grail’s wounded custodian, the Fisher King, can be released from suffering by one who becomes conscious that he shares such a wound. Jung’s calls this process in which the solution to a systemic conflict emerges the Transcendent Function.

The embedded intelligence from which symbols, and myth arise is autonomous. It doesn’t depend upon or necessarily reference discursive intellect. Often, the shifts in attitude take place under the radar and are communicated in the language of dreams. The deep nature of conflict addressed at this level can’t be resolved by reason or custom. And the resolution arrived at can only be described in the telling or enactment of a myth.

Wolfram gives us a myth within a myth which locates the origin of his tale in a war waged in heaven between the angels of light and darkness. It is the neutral angels who descend to deliver the Grail, a symbol of wholeness, to us. Origen of Alexandria in the 2nd Century also speculated that the creation of the world as we know it was born as an answer to heavenly conflict.

In our time, quantum physics has shed light on what earlier had been beyond our grasp: at a sub-atomic level matter and energy, particle and wave, are interchangeable. The speed and direction of these particles can’t be known at the same time, and the form one will take depends as much on the observer as the observed, and can be discussed only in terms of probability. The relationship of energy to matter exists as fact, but remains unimaginable to the naked eye. This resolution is a measure of our time, free of symbolic/mythic content. At best, it leaves us with uncertainty.

I remain drawn to the idea of the Fisher King, but he, too, has become difficult to recognize. The myth in which he is rooted compels me, but no longer describes the challenges that shape my world—the G-Force rate of change, geometries recognizable only in virtual space, the suspended alternatives of “super states,” and a cosmology that points to a multi-dimensional universe.

How might any prospective Parzival penetrate the intuition of a realm beyond intuition?

Physicist Irwin Schrodinger’s model of the atom as a solar-system fell apart because the image no longer described the electron’s behavior. Without it, the atom became unimaginable. Wolfgang Pauli, who’d deconstructed it, assured his colleagues that an image would emerge in time to embody what waited faceless in the dark. Albert Einstein understood that the mystery of our condition is more deeply apprehended when it looks back at us. If not, we are gazing into the abyss. Without recognizable landmarks, we are lost at sea.

*

I glimpsed the Grail in the marlin’s eye, and immediately recognized what stared back at me as “the Divine Child.” In my book, Fishing on the Pole Star, I record watching “the unconscious conscious of itself” swim away on release to disappear into the primordial depths. What good is that unless something is born from it, seed of my heart-break?

I remember that glimpse even as I reel in the projections of our collective fears. They are recycled Victorian nightmares with a post-modern flourish: Dr. Frankenstein masters the genome, Dracula transforms into a vampire rock-star, only to be superseded by legions of viral zombies which define our war with creeping numbness. I cling to the hope that longing, even expressed as anger, will “pierce through” the callous thickening around our humanity. It is unclear what might deliver our cultural psyche under the assault of constant stimulation that leaves us dumb in an avalanche of words.

Arthur Dove: Me and the Moon

Arthur Dove: Me and the Moon

The neutral angels might want to reconsider their strategy and take the Grail back to the war in heaven—reboot the Transcendent Function.

This is not where I thought my troll would end, with a suspicion that the entire mythos, and the psychological underpinnings of symbol formation itself, are no longer reliable.

I began this journey trolling with the Fisher King, and ended it with Justin, crowned by headphones, weeping for the doomed singer, Tosca, who rises on soiled wings to relocate human pain in the sublime. Justin as wounded Amfortas points to what we are both missing, the divine breath that carries such a voice: Vissi d’arte, I lived for art/ Vissi d’amore, I lived for love. In Tosca we glimpse the World Soul, the interstitial presence connecting visible and invisible realms. Not a particle that leaves no footprint, unless it is possible to imagine a suffering neutrino. Tosca, a recognizable aspect of the World Soul reminds me of words by Leo Stein: “Though the mole is blind, the earth is one.”

The World Soul exists in and out of time.

The philosopher Alfred Whitehead suggests the World Soul has two components, the unchanging primordial, and the consequent nature that shares our experience. The Primordial abides but is informed by the consequent that unfolds in space-time, shares in our suffering and joy, and is changed by it. From that point of view, the archetype of the Fisher King, like all expressions of eternal forms, is beyond our grasp. What we visualize as the Fisher King, the figure on the stern of a skiff, is our idea of the archetype, and subject to events beyond our control. It is possible, even inevitable, that changes will re-shape the ideas we thought unchanging in ways that make them unrecognizable, like gods disguised as beggars.

Wayne Atherton: Spider Mind

Wayne Atherton: Spider Mind

Wolfram makes it plain that neutral angels brought the Grail to earth to save it. More than the danger posed by warring angels, the Grail’s descent into our world replicates the Transcendent Function, the active principle of the World Soul. A symbol, Jung tells us, is alive to the extent that it expresses “the immutable structure of the unconscious.” Only such a symbol and healing mythos can address the challenge that pits us against our “nullification.”

We live at the center of a mystery that nothing prior to the present moment can cipher, uncertain how the Transcendent Function will eventually respond to what can’t be imagined.

Something vital to the World Soul pins us to the production of symbols, myths, and dreams that inform its primordial aspect, and the consequent one in space-time that flows in sympathy with our condition. It may be that I no longer recognize the Fisher King or Parzival as I had at one time conceived of them. The changes to our archetypal ideas may be our greatest hedge against nullification. The Grail, that had been an external principle of restoration and balance, may best be realized now as an internal potential. We are each us a Grail, in which warring and neutral angels continue to give birth to the Transcendent Function.

This is where we find ourselves

On soiled angels’ wings

This is the way we come to the end

The way the end comes to us

.

—by Paul Pines

.

Paul Pines grew up in Brooklyn around the corner from Ebbet’s Field and passed the early 60s on the Lower East Side of New York. He shipped out as a Merchant Seaman, spending August 65 to February 66 in Vietnam, after which he drove a cab until opening his Bowery jazz club, which became the setting for his novel, The Tin Angel (Morrow, 1983). Redemption (Editions du Rocher, 1997), a second novel, is set against the genocide of Guatemalan Mayans. His memoir, My Brother’s Madness, (Curbstone Press, 2007) explores the unfolding of intertwined lives and the nature of delusion. Pines has published ten books of poetry:Onion, Hotel Madden Poems, Pines Songs, Breath, Adrift on Blinding Light,Taxidancing, Last Call at the Tin Palace, Reflections in a Smoking Mirror, Divine Madness and New Orleans Variations & Paris Ouroboros. The last collection recently won the Adirondack Center for Writing Award as the best book of poetry in 2013. His eleventh collection, Fishing On The Pole Star, will soon be out from Dos Madres. Poems set by composer Daniel Asia appear on the Summit label. He is the editor of the Juan Gelman’s selected poems translated by Hardie St. Martin, Dark Times/ Filled with Light (Open Letters Press, 2012). Pines lives with his wife, Carol, in Glens Falls, NY, where he practices as a psychotherapist and hosts the Lake George Jazz Weekend.

.

.

With Uncle Henry’s boys at The Knoll, c.1950

With Uncle Henry’s boys at The Knoll, c.1950 Essie on the right beside my father and me. My sister seated by Grandfather, Uncle Aub and the Vauxhall Tourer, c.1951

Essie on the right beside my father and me. My sister seated by Grandfather, Uncle Aub and the Vauxhall Tourer, c.1951 At the lake with my father, c.1953

At the lake with my father, c.1953 Me in the late 1980s, not long before The Knoll was sold

Me in the late 1980s, not long before The Knoll was sold

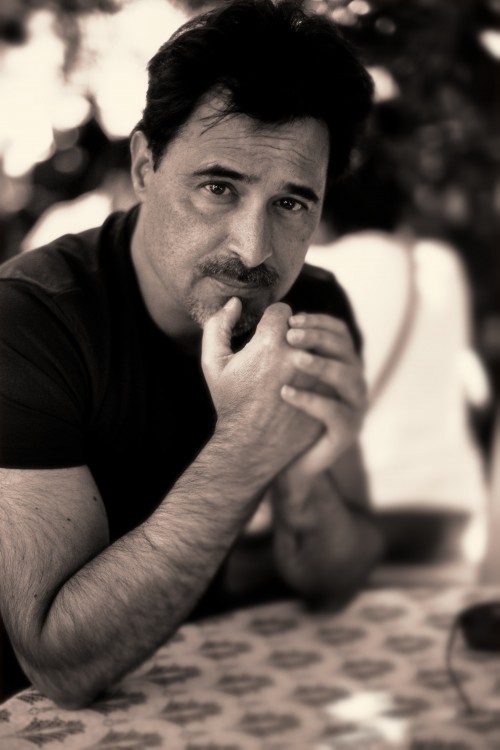

Author photo by Alexandra Pasian.

Author photo by Alexandra Pasian.

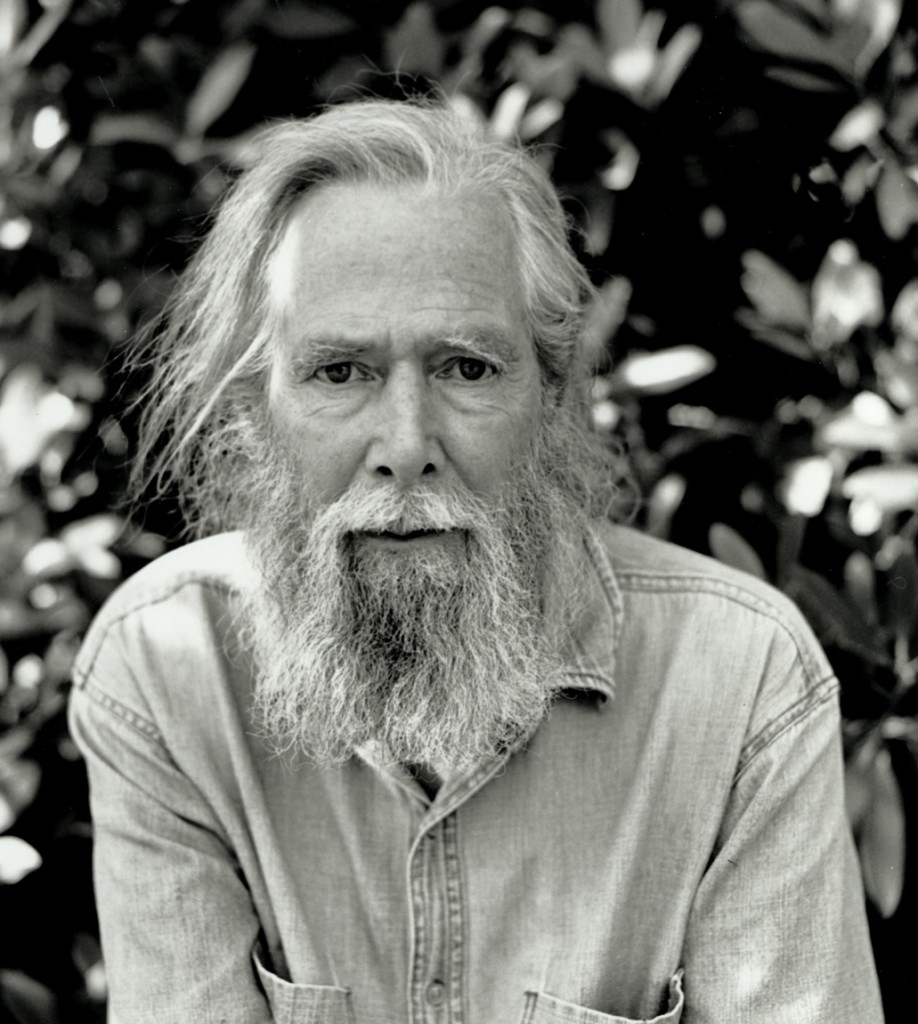

Anita Desai

Anita Desai

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Among the Long Shadows

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Among the Long Shadows Marsden Hartley: Lighthouse

Marsden Hartley: Lighthouse Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water Tarot (Alphonse) Mucha: Queen Of Cups

Tarot (Alphonse) Mucha: Queen Of Cups  Wayne Atherton: Cover, Fishing on the Polestar

Wayne Atherton: Cover, Fishing on the Polestar Richard Saba: Ancient Clamor

Richard Saba: Ancient Clamor John Marin: Marin Island

John Marin: Marin Island Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Eclipse

Toyen (Marie Cerminova): Eclipse Herman Maril: Province Town

Herman Maril: Province Town Djorde Ozbolt: Monkey Business

Djorde Ozbolt: Monkey Business Arthur Dove: Red Sunset

Arthur Dove: Red Sunset Percival’s Quest, 1385-1390

Percival’s Quest, 1385-1390 Frank Auerbach: Head of E.O.W. (1955)

Frank Auerbach: Head of E.O.W. (1955) Kenneth Armitage: People in the Wind

Kenneth Armitage: People in the Wind Paula Rego: Angel

Paula Rego: Angel Paula Rego: House Underground

Paula Rego: House Underground Anselm Kiefer: Let the Earth Be Opened and Send Forth a Savior

Anselm Kiefer: Let the Earth Be Opened and Send Forth a Savior Francis Bacon: Lucien Freud

Francis Bacon: Lucien Freud Dragon King

Dragon King Paula Rego: Vanitas (pastel, 2006)

Paula Rego: Vanitas (pastel, 2006) Robert Fludd: Temple of Music

Robert Fludd: Temple of Music John Marin: Sunset, Casco Bay

John Marin: Sunset, Casco Bay Peter Reginato: Yellow Interior

Peter Reginato: Yellow Interior Kusama: The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away

Kusama: The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away Wayne Atherton: Everything Is Permitted (collage)

Wayne Atherton: Everything Is Permitted (collage) Roy Laewetz: Three Fishing Ladies (detail)

Roy Laewetz: Three Fishing Ladies (detail) Albrecht Durer: Melancolia I (detail)

Albrecht Durer: Melancolia I (detail) Paula Rego: Dame with a Goat’s Foot

Paula Rego: Dame with a Goat’s Foot Darren Tunnicliff: Quantum Entanglement through Time

Darren Tunnicliff: Quantum Entanglement through Time Arthur Dove: Me and the Moon

Arthur Dove: Me and the Moon Wayne Atherton: Spider Mind

Wayne Atherton: Spider Mind

Cemetery in Sarajevo

Cemetery in Sarajevo Restaurant near Skakavac waterfall

Restaurant near Skakavac waterfall Goran Simić relaxing at Aladinići

Goran Simić relaxing at Aladinići

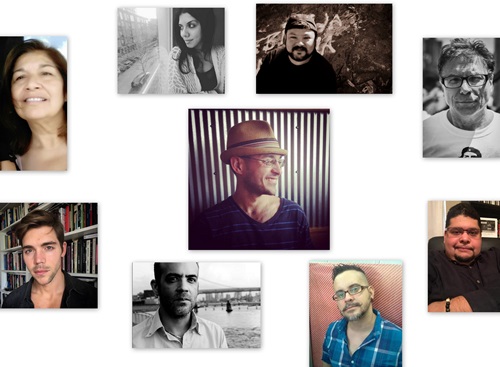

Jonathan Marcantoni (center); Clockwise from top left: I. C. Rivera, Ricardo Félix Rodríguez, Nelson Denis, Rich Villar, David Caleb Acevedo, Charlie Vázquez, Chris Campanioni, and Corina Martinez Chaudhry.

Jonathan Marcantoni (center); Clockwise from top left: I. C. Rivera, Ricardo Félix Rodríguez, Nelson Denis, Rich Villar, David Caleb Acevedo, Charlie Vázquez, Chris Campanioni, and Corina Martinez Chaudhry.

David Caleb Acevedo (San Juan, 1980). Writer, painter and translator. His books include Desongberd, Cielos negros, Diario de una puta humilde, and Hustler Rave XXX: Poetry of the Eternal Survivor. He is pansexual and lives with his husband and three adorable cats.

David Caleb Acevedo (San Juan, 1980). Writer, painter and translator. His books include Desongberd, Cielos negros, Diario de una puta humilde, and Hustler Rave XXX: Poetry of the Eternal Survivor. He is pansexual and lives with his husband and three adorable cats. Corina Martinez Chaudhry was born in New Mexico but has lived in California most of her life. She grew up in the San Joaquin Valley throughout her high school years, but then made the transition to Southern California where she now resides. Her maternal grandparents were from Chihuahua, Mexico; however, her grandmother was half Basque (Spanish/French). Her paternal grandparents were of Mexican and Native American descent. She graduated from Vanguard University Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in business and a minor in English. In addition, she has completed a Water program through the California State University of Sacramento, alongside a Management Certification Program through Pepperdine University, and currently manages The Latino Author Website.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry was born in New Mexico but has lived in California most of her life. She grew up in the San Joaquin Valley throughout her high school years, but then made the transition to Southern California where she now resides. Her maternal grandparents were from Chihuahua, Mexico; however, her grandmother was half Basque (Spanish/French). Her paternal grandparents were of Mexican and Native American descent. She graduated from Vanguard University Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in business and a minor in English. In addition, she has completed a Water program through the California State University of Sacramento, alongside a Management Certification Program through Pepperdine University, and currently manages The Latino Author Website. Ricardo Félix Rodríguez (Sonora, México 1975). Writer and psychologyst. His books include The surreal adventures of Dr. Mingus, Asgard: a Saga dos nove reinos, There is No Cholera in Zimbabwe, and The Other Side of the Screen (contemporary writers of Poland).

Ricardo Félix Rodríguez (Sonora, México 1975). Writer and psychologyst. His books include The surreal adventures of Dr. Mingus, Asgard: a Saga dos nove reinos, There is No Cholera in Zimbabwe, and The Other Side of the Screen (contemporary writers of Poland).