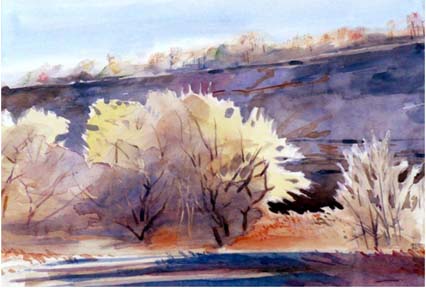

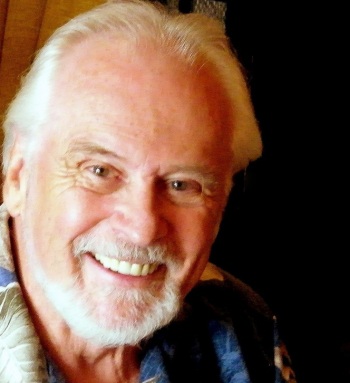

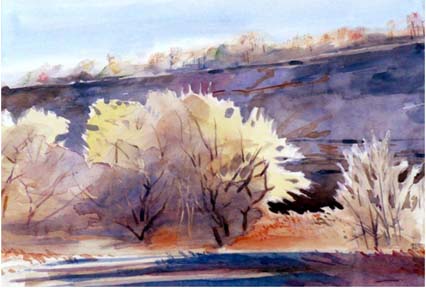

Harry Marten writes here a lovely essay on rivers, river books (Huck and Ratty and Mole) and cancer, the beauty and whimsicality of the one and the grim treatment protocols, anxiety and dread of the other. Born in the Bronx, Marten has spent most of this life living next to the Mohawk River a few miles from where it drops over the falls at Cohoes and joins the Hudson (so he is practically a neighbor of mine). We have also gorgeous paintings by Marten’s wife Ginit Marten of the river that is so precious to them both. Marten is the Edward E. Hale, Jr., Professor of Modern British and American Literature at Union College in Schenectady, also a Conrad Aiken expert which endears me since Aiken has been a teacher and inspiration to me since I cracked open The Divine Pilgrim at the feet of the two-story reproduction of Michelangelo’s David in the library reading room at the Loyola campus of Concordia University in Montreal in 1975.

dg

Mohawk River, Niskayuna

§

Living on the river was nice and easy./People on the river just take their time. / The wind in the summer was warm and breezy. / Wind in the winter, it cut like ice. (Folk Song)

There is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about by a river. (A.A. Milne, play version of The Wind in the Willows)

Some childhood things just stick in the mind. Water Rat from The Wind in the Willows, for instance, forever confident, offering words to live by: “’And you really live by the river? What a jolly life! . . . .’`By it and with it and on it and in it . . . . It’s brother and sister to me, and aunts, and company, and food and drink. . . . It’s my world, and I don’t want any other. What it hasn’t got is not worth having, and what it doesn’t know is not worth knowing. Lord! the times we’ve had together! Whether in winter or summer, spring or autumn, it’s always got its fun and its excitements.’”

But despite Ratty’s words of wisdom, read to me by my sweet father before I had many words of my own, my life remained essentially riverless for more than five decades. There were plenty of ponds, lakes, oceans, even a reservoir or two, but no river contact to speak of.

For a boy in the 1950s Bronx, the river – East or Hudson – seen through the back window of the family Plymouth driving south to visit aunts and uncles in midtown, seemed to confirm Ratty’s enthusiasm. The shining water was lovely and beckoning. But up close, it was a free flowing garbage dump and a danger zone, home to muggers and addicts. Well known myth had it that even putting your foot in the river was to risk rot or worse; and to walk the shoreline after sunset meant becoming the crime written up in the morning Daily Mirror headlines.

There were always satisfying encounters with imagined rivers, growing in number as I ambled into adulthood — Marlow’s voyage into African darkness, Huck’s raft on the Mississippi, Lewis and Clark on the Columbia and Yellowstone, Thoreau’s Concord and Merrimack. But when it came to actually looking at, touching, smelling the thing itself, I found that I had little desire to muck about by or in, or with or on any river. Even when I lived near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri for six years, I hardly ever looked up from my work of teaching and paper grading to notice their majesty. When the tropically hot St. Louis summers oppressed our young family, my wife and I followed Huck’s example and lit out for the territories – but not on a river. We were looking for a lake or a beach. We never tried float tripping on the Missouri, the proscribed summer get-away activity for locals; it just wasn’t part of our sense of how the world worked. Instead, we drove hours south to the tacky Lake of the Ozarks, and days north as far as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, to find a plop-down beach and cool water. For all the impact America’s great rivers made on me, I might as well have been living in the Mohave Desert. Which is why I was surprised to find myself well into my fifties living alongside a river and liking it.

More than half a dozen years ago, having decided that we’d better do it soon if we were ever going to move from our clattery but comfortable city neighborhood in upstate NY where we’d been just about long enough to pay off our mortgage, my wife and I began to spend our weekends with a workaholic realtor. She showed us suburban ranches in lawnville, country estates where I could pretend to be a small-scale Rockefeller, woodsy cabins ripe for improvement, and upscale colonials crammed with enough electronic gizmos to light up the darkest nights. But nothing clicked until the house on the river swung into view. For all practical purposes the deal was struck before I’d even finished locking the car.

My wife and the realtor had gone inside while I stayed back on the driveway for a minute to enjoy the late spring sunshine before following along behind. It was as close as I’d ever come to a Sunday Times Magazine kind of place, skylights and windows filling each room with light and air. The vaulted ceilings were a plus; and the huge two-sided brick fireplace with coppery arched doorways was a knockout. But it was the view that did it, the house set high above the Mohawk River, with a wetland at the base of the river bluff. Along the back of the house, every window, every door, looked out toward the water. I loved the idea of “my river.” That afternoon it was brown and placid, moving slowly south and east toward its grand finale with the Hudson a few miles down the line.

Filled with desire, we bargained badly, pushed ourselves to the limit of our money, said yes, we’ll do it. We hired Mr. Sandman to awaken the gloss of the hardwood floors. We had the place inspected, the shale-driven radon gas remediated with a pricey vacuum system. We tried to persuade our grown sons that we weren’t abandoning their history or their boxes of comic books, vinyl records, Star Wars figures, Transformers, old Tin Tin stories, secret diaries, stuff they could neither use nor throw away. We moved out and moved in, leaving our three story urban Victorian in order to discover a new domestic world in the semi-tamed water wilds.

The blur of the first months became the blur of the first years. Boxes filled the basement and garage, waiting to be unloaded while we lived without really settling in. We went about our business of work and play, noticing the river and the wetland in passing when a big boat went by, or when a heron landed to feed and preen down below our windows. We kept binoculars hanging in the kitchen so we could spy selectively on river life. But for the most part the river neither demanded nor commanded our steady attention. Until the late winter of our fourth year, that is, when normal became abnormal and routine stopped dead in its dull and predictable tracks.

There was nothing unique about the moment, which had to have happened many times that day and every day on the east coast and the west, in the breadbasket middle of the country, in faraway places I’d never visited or thought to visit. It wasn’t even a first in the family; but it was a first for me and it changed things. Though my wife had had three cancers in ten years, this was my turn, and it came as a surprise.

The clue, I suppose, was the doctor’s office calling to give me the last appointment of the day — “so you and Doctor can talk,” the receptionist said.

“Why do they always call them ‘Doctor?’” I groused to my wife – “like they’re the only one of their kind.” Of course I was nervous and showing it, but I’d really had no negative vibes. My PSA numbers weren’t very high, though they’d been slowly and steadily moving up and lately had jumped. The obligatory biopsy had been humiliating, but painless, and Dr. R., an experienced surgeon even if he looked younger than my children, had told me that this was just a precaution. He didn’t expect cancer, and if he didn’t, I didn’t.

The last appointment of the day takes you out of the examination room and into the comfy chair room, the office with leatherette chairs, lamps instead of neon, a grand oak desk. Everyone, it seemed, had left for the day except me, my wife, and Dr. R, who was quiet, serious, kind, as he explained that much to his surprise the biopsy had been positive, and not only that, my “Gleason Score” – the way of measuring the irregularity, and therefore the aggressiveness, of prostate cancer cells – was near the top of the scale. I had “It,” and a particularly dangerous version of it to boot. With the February evening turning cold and dark outside the office window, Dr. R offered a sobering pep talk. For someone my age, he recommended a radical prostatectomy, surgical removal of the offending organ, as the procedure with the best survival statistics; but he urged me to take my time in deciding what action to take.

There were plenty of choices, from radiation to cryotherapy, leaving me with bizarre echoes of Robert Frost’s world-ending visions of fire and ice spinning round in my literature professor mind. The one option that Dr. R. refused to sanction was the one I wished for: do nothing now, simply watch and wait. Maybe all of this would take care of itself, turn out to be no big deal after all. I knew better, of course, and handing me a “Prostate Cancer and You” pamphlet, and a list of books I could find at my local Barnes and Noble – everything from Surviving Prostate Cancer by the grand Pooh Bah of Urological Surgeons, to the Prostate Cancer entry in the Dummies series – Dr. R urged me think it through so that I felt comfortable in my decision. The books would clarify, he said.

“Take your time,” it turns out, means take up to four weeks if your Gleason rating is 9 on a 10 scale, hardly a blink when contemplating actions that might leave you incontinent, impotent, or, in a worst case scenario, dead as Marley’s ghost. Not to mention that second opinions typically come from doctors who are booked out months in advance, not weeks. The decision-making tied me in knots – everything that followed was simply a predictable, and therefore manageable, misery.

Too tired and too wired to go home for dinner after the diagnosis, my wife and I ate at our favorite family Italian restaurant. I won’t say that it had become a kind of ritual meal for the condemned, but pasta is powerful comfort food, and we had gone there after my wife had gotten her first cancer report. Then we had been profoundly shocked and disbelieving. Now, ten years and three other cancers down the line, our reaction after the first hour was “OK. Now what do we have to do?” That answer, at least, was clear: like the old Fred and Ginger song said, you’ve got to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and start all over again. The problem was that only we could decide where to start and how to start this time through.

Oddly enough, one of the things I most remembered from our first encounter with the disease was a trip to the MOMA in New York to see Willem de Kooning’s late paintings. The old man, his disruptive, alcohol-fueled creative rage replaced by a growing calm that came, sadly and ironically, with the onset of dementia, had in the 1980s produced paintings that were fluid ribbons of bright color, objects of great beauty that seemed to offer openness, simplicity, and movement as an intuitive response to gathering darkness. On a weekday afternoon, the museum almost deserted, we’d walked through the show contemplating the sense of sadness, but also the wonder and freedom at the end of life.

A gift from an unexpected source, I thought, next morning, standing in front of the show’s poster that hangs alongside a cactus many feet taller than I am on a second floor landing of our house. Below a large arched window looking out to the river, de Kooning’s ripples of color and light seem to speak to the always moving dark but sparkling water down below. And that’s where my eyes and thoughts turned those first weeks of decision-making – gliding past de Kooning to the river in winter.

When I wasn’t making arrangements for time away from work, seeing to medical consultations, or discovering in my stack of “how to” cancer books that the subject turns from treatment options to survival statistics when the text shifts to cancers at the top of the Gleason scale, I found my attention drawn to the waters below the house. While my world seemed to be uprooting, as if slowly tilting down an embankment, the river stayed firmly horizontal, always changing yet visibly stable. In February’s sharp light, unobstructed by leaves or cat tails, the river seemed a study in contrasts. Blocks of ice capped by mounds of snow formed great uneven ridges across the channel between our street and “Riverview Road” across the way. But the surface of the water seemed uniformly dark in the early morning, then mirror-flat and shimmering in the cold afternoon sunshine. Contemplating the water, I tried hard to keep my own surface appearance steady in public view, masking the surges of fear and stress that pushed me into turmoil.

My days were filled with a new language, words I’d lived happily without for six decades—abstract, scary words that were hard to grasp because I was bent on forgetting them as soon as they reared up into my consciousness: bladder neck contracture, external-beam radiation, laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy, neurovascular bundles, surgical margins. Some of it was military: there were “zones,” “invasions, “blockades.” Some of it sounded like a collision of Freud and up to the minute sociology – all about “urges” and “dysfunction.” At its best it was a distraction, a chance to practice my standard coping mechanism of irony. At its worst, it was an open sesame into a world of pain and diminishment. Unable to concentrate on pop medical books with catchy chapter titles like “Diagnosis and Staging” and “What Are My Options,” half-hiding, reading as if I was holding my hand up to my eyes, fingers spread wide, so I could see and not see at the same time, I found myself looking more and more toward the steadying river that in its indifference to its surroundings, its regular unflustered downstate movement past my house, never failed to calm and clear my mind.

The Mohawk travels roughly 150 miles from its start as a tiny stream 35 miles or so north of Rome, NY, flowing generally south and east across New York’s Mohawk Valley through small towns and cities that mix Indian and European names – Oriskinay (“the place of nettles”), Canajoharie (“the pot that cleans itself”), Alplaus (“eel place”), Schenectady (“across the pine plains”), Niskayuna (“flat land where the corn grows”) – down to Cohoes Falls where it spills some 70 feet down into the Hudson Valley. My own slice of the river, looking full left and right as far as the eye can see from the dining room window without precipitating neck spasms, is about three-fourths of a mile. The mystery of the unknown, both upstream and down from my window on the watery world, absorbs me. Often my puzzling extends no farther than wondering where that log that’s floating past me broke loose, or when will the ice be breaking up again with its loud and sudden rifle cracks. But faced with my sudden awareness of time’s limits, a standard subject, of course, for the novels and poems I’ve been teaching for decades but which I seem not to have absorbed viscerally until just yesterday, I find myself wondering too about the history of the place where I’m standing – fifty years ago, one hundred, two hundred.

On their ways west, how many may have casually looked up to exactly where I’m standing? Did they continue far beyond the bend in the river, or did they stop nearby, set down roots, raise families? Remembering my grandfather who once was a Canadian fur trapper, I think about the European traders who worked the river, and the Indians who were displaced. Remembering the old bridges I’ve driven across lately, I wonder if there were wooden bridges before iron and steel. What happens to old things along the river, no longer useful, no longer wanted? Do they simply rot and crumble, finally drifting away, never to be seen or thought of again? Will any of the riverside construction I see each day be here when my grandchildren are old enough to notice it? What about the roads now jammed with workers headed into and out of the city? Or the Country Club a river’s width away, that fires glorious tracers into the night sky to celebrate weddings, graduations, and our national independence? The apple orchards down the road, a delicious autumn destination? I’ve no capacity to think in geologic time, of the slow dance of glacier melts and deposits tens of thousands of years ago. Of course I understand that things are always starting and ending; but I know, too, that for all practical purposes the river continues, which is, during these days of uncertainty, a comfort.

Two weeks after my sit down with Dr. R. I have an appointment for a second opinion. The Head of Oncological Radiology at the hospital is a slender, confident, middle-aged guy, whose office lies deep within the bowels of the building. To get there, my wife and I are instructed to follow the color coded stripes painted on the floor. Like Hansel and Gretel we keep to our trail of breadcrumbs, which takes us eventually to Elevator C and then to who knows what witch’s house in the windowless basement.

Though he must have a version of this conversation many times a week, Dr.S. is polite, attentive, unhurried. He reads through the chunky file of my medical history, sits forward in his swivel chair, leans into the conversation. He pulls out a yellow pad and begins to draw what he figures is going on inside my body. He talks about clinical “staging,” writes out a dizzying assemblage of numbers and letters that are used to indicate how virulent and how far along a tumor might be, offers a preliminary number and letter for my version of the beast – the bad news being my Gleason score; the good news being the likelihood of this being an early discovery of the tumor.

He explains what radiologists do: 3-D conformal radiation; intensity-modulated radiation therapy; proton beam radiation. Like the good student I have always been, I take notes like crazy, filling up pages of my notebook with fragments of techno-talk. As far as I can tell, all the radiological options do the same thing, burn and destroy tissue, trying to keep to a minimum the damaging of healthy cells while killing the killers. Then the risks and side-effects part of the conversation: inflammations, burnings, itchings, crampings, blockages, bleedings, strictures, pain that won’t quit, various diminishments and/or collapses of body functions. This fills up 20 miserable minutes, escalating to anecdotes about worst case scenarios, like the one about a man who has been compelled to use a Foley Catheter for more than a year because he has lost the ability to urinate, before Dr. S. tells me that he simply wouldn’t recommend any kind of radiation for a patient like me – strong enough to tolerate surgery, young enough to expect long life after a procedure, early diagnosis, likely for various reasons to have urinary “issues” after any sort of beam treatment. It’s hard to argue with a man who turns away business.

After extravagantly praising Dr. R’s surgical skills and reputation, he talks about my surgical options. The more he explains, the more anxious I become. Though I need to understand what’s coming my way – it is, after all, why we are spending our “second opinion” afternoon together – what I suppose I’d like to hear from him, though I’d not admit to it, is “do it this way, and do it now.” I’d resent and distrust his certainty, but I’d be able to get on with my planning. Instead, covering the same ground that Dr. R. and the books have mapped, he explains my two options. There’s the old way, traditional open surgery with the surgeon’s hands doing the cutting and in the body, and the surgeon’s senses of touch and sight immediately engaged; and the new way – robotic surgery performed by working a robot from behind a computer screen. Both procedures take you to the same place – removal of the cancerous organ and the cancerous tissue that may surround it. But the robotic is initially less invasive, less traumatic. The hospital stay is likely to be shorter, initial recovery quicker.

It seems a no brainer; less pain never loses its appeal. Until he begins to talk about survival statistics, which are generally good for the old ways and “too soon to call” for the new. He says we just don’t have enough data to know if robotic surgery is as effective a treatment as open surgery. Maybe in ten years everyone will be dancing with robots, but now, in this part of the country, it’s only a few, and they’re finding their way as they go. “Want to be part of their learning curve?” he asks, pointing out that Robotic surgery might well add three to five hours to the time of an already long operation, and every hour under anesthesia comes with the risk of brain cell damage. “How many cells can you afford to lose?” he asks?

The issue of being on the “cutting edge” has never taken on so precise and troubling a meaning. Dr. R practices the old tried and true method and has done many hundreds of these surgeries, a statistic that both pleases me and makes me cringe. Does it matter that I’ve known and liked him for years, and if I switch to the latest technology I’ll just be encountering another surgeon for the requisite 6-8 hours of the procedure – being asleep for much of that time anyway? Should it matter? Am I comfortable with a doctor behind a monitor, a position that he probably hasn’t assumed all that often before seeing my inner organs in, I hope, vivid Technicolor? Working all my adult life with metaphors not numbers, I’ve always been likely to come down on the side of Disraeli’s “there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” But the stats I have before me speak to the possibility of my living or dying, and the debunking quote suddenly seems too cute and coy. Pondering my Gleason score again as I gather up the diagrams and my scribbled notes to leave, trying to untie the tight knots in my stomach, I find myself hearing the explosive frustration of that other Gleason, Jackie, delivering Ralph Kramden’s Honeymooners line: “one of these days . . . . one of these day, POW, right in the kisser.” But is it my POW or my kisser?

If I could just leave the sickness books and notes behind, I think, even for a day or two – take a walk along the river, looking downstream toward the nearest river lock, letting the water and winter sky clear my view of things while all the accumulated information simply moves through me, like river tributaries, I’d know what to do . But the February freeze holds into March, and the ice and snow along the riverbank makes walking impossible. All I can do is look out from the safety of my cliffside perch to the uniform gray of the scene below, hoping to be able to differentiate distinct shapes.

With a smile, my brother-in-law tells me about a busy CEO who picked his treatment and his doctor by finding the place and practitioner nearest to his weekly staff meetings. A friend, snipping the grape vine, recommends a doctor that another has told me to avoid at all cost. A colleague tells me that in Europe they rarely cut, just wait. Gotta die of something, he says. I make and break an appointment for yet another medical opinion. Time’s running along, and caution or confidence, I’m really not sure which, keeps bringing me back to the place I began – the doctor I know best and the operating technique that has been around longest.

Much to my surprise, by the time I look up from my intense preoccupation with next steps and survival strategies, the seasons have shifted. Ice jams have broken, and the surging river is carrying its usual early spring load of winter detritus – wrecked trees, beer cans, even an occasional abandoned cooking grill and kitchen appliance – down toward the falls at Cohoes. My own stumbling rush to determine and set up my procedure –carrying its full load of fear and other psychic waste suddenly released into turbulent flow of my thoughts – has bumped to a halt against the reality of the surgeon’s schedule and operation room availability. Now knowing more than I care to about my body and the state of prostate cancer treatments, I spend the next month ducking thoughts of pain, disease and death, until finally I’m summoned to unload my medical history and get clearance at a series of pre-op appointments. My internist confirms that except for this disease I’m basically fit to go. A cardiologist says, yes, my heart is beating. I’m scanned and screened, listing again and again the meds I take, other illnesses and surgeries I’ve had, including childhood miseries like mumps and chicken pox. They ask if there’s a history of cancer in the family, but what can it matter now that I’m not a statistic of possibility but an actual happening?

The admissions clerk who takes my insurance information tells me that she once had a parakeet named Harry. This bird, she says, was remarkable – talkative, with a large medical vocabulary, given to eating table scraps right off the plate, sleeping right on her shoulder during the early evening TV news broadcasts. It flew out the window one summer morning and she hasn’t seen it since. It’s probably dead, she figures, giving me a hard stare as if I were the bird reborn. Sad news, I say, wishing I could fly out the window with my namesake. Good luck, she says, chirpy.

Next morning at the hospital I’m banded like Harry the parakeet, ready to be tracked. Outfitted with a flapping hospital gown and a green hair net, an IV tube that will travel with me for days, I climb up on the gurney that will be my bed for the day. I’m attached to a host of machines that monitor blood pressure, blood chemistry, heart beat. A nurse asks me how I respond best to indicating pain – visually, with a series of smiley and frowny faces that will mark my threshold? Numerically on a 1-5 basis with 1 equal to no pain and 5 as cataclysmic? With actual words like extreme, moderate, mild? I opt for words, as they seem to me to offer the best chance for maintaining dignity. I have one final go at the toilet, a first and last conversation with the anesthesiologist, a jokey exchange with Dr. R about how well rested we both feel, then surgical oblivion.

I wake to nurses flowing around me, like quick water round a floating tree trunk. One leans in to welcome me back, to ask how I’m feeling, to tell me that Dr. R. has already come by and that all went well, though I remember nothing of that and can’t really focus on what it means. He has explained it all to my wife, she says, who’ll be coming in from the waiting room any minute now. Slowly I understand that I’m in the recovery room, fuzzy headed, tightly and heavily wrapped around my belly with some kind of surgical bandages, and, oddly, down near my ankles, fitted with pulsating leggings that rhythmically squeeze blood through my legs and thighs to prevent clotting. I seem engulfed by a spider web of tubes – some, like the catheter and drain, will be my unwanted constant companions for many days; others are just for the post-surgical moment, part of testing and measuring my return to the world.

I seem to have questions, but the words I form disappear before they can get from somewhere inside my head to out my mouth. I feel muddy and sluggish, and when my wife comes in, she simply sits, her hand on mine. Later, when I can listen, she tells me the news – no apparent metastasis, margins and lymph nodes clean. The downside is that given the aggressiveness of the cancer, not all of the nerve bundles on either side of the prostate, the nerves that enable erectile function, could be spared. What I know is that I am still in the world, a doped but recognizable version of myself. The rest, for now, is abstract – issues for some future recovery time.

The nurse who greets me in the place where I’ll be parked for the better part of a week is efficient and cheerful. She demonstrates the morphine drip that I can use for pain control. Just squeeze here, she says. It won’t do more than two jolts every twenty minutes, but that should be plenty. If you need assistance, she says, just press this button –it’s what I’m here for. I’ve got the room to myself, though a plaster Jesus hangs above me on each wall, watching. It’s part of the ambience of this Catholic Hospital, the trade off, I suppose, for having private rooms available. His repeated presence on the cross, wracked with pain for all our sins, speaks to my physical discomfort, unsettling the room. The body is what preoccupies me, not my spiritual well being, and if I could move, I’d take him down. Maybe if I ring a nurse she could take the little Jesuses away. Within minutes, drifting in and out of sleep, I hardly notice them.

The nurses, arriving and departing, mark the minutes and hours of my new days. Every half hour they come to write out the statistics that represent me. When chills and fever flash through me, they shift the cocktail in my IV drip. When my catheter bag is full, they drain it, measuring my urine before they carry it to the toilet. They change my sweat soaked sheets and gown, barely disturbing me. Some are chatty and playful, some quiet, a few somber, cheerless and put upon. With all of them those first few days I try hard not to be a bother; my goal is not to be noticed at all. Perhaps I’m guided by an instinct of appreciation and cooperation. Or maybe it’s just a way of fooling myself into feeling that I’m not really helpless. The puzzle that no illness guide books prepare you for is just how to give over with grace to being suddenly needy after a lifelong habit of independent action and coping.

As if to throw that question at me, a man I can’t see, but who is clearly in his own world of pain across the hall, screams his discomfort constantly in a voice that can’t be calmed or ignored. “Nurse, Nuuuuurse, NURSE”—he shouts it over and over – “Help me.” It comes in waves slapping against the walls of my room, and every room within reach. It kills sleep.

I try to picture my vocal neighbor, frightened and shocked by a kind of pain that’s completely new to him. I want to walk out into the hall, grab the first nurse I see, guide her into his room. “See,” I’ll say, “this man needs you. Do what you can for him. Do what you should for him.” But for now the best I can manage is to be still, somewhere between lying down in a heap and slumped up in bed. “What’s going on over there,” I ask when a young nurse stops by to run a magical thermometer around my forehead and the side of my face. Not to worry, she says, they’ll get him sorted out. But the wailing goes on, endlessly. Later, when my wife comes in, she shuts the door behind her to dampen the noise. Next time it’s earplugs all around, I say, half smiling. Maybe it’s the morphine haze speaking out of my mouth, or my own pain answering his. Or maybe it’s the real me coming out at last under duress. I’d like to choke him, I think, Duck Tape his mouth – just enough to bring peace to the surgical recovery wing.

Ever accommodating, Dr. R. manages a room change for me. But to my surprise, by mid- afternoon of my second day, I hear loud and clear from just across my new stretch of hallway, “NURSE. NURSE, Can’t anybody help me?” – as steady as Ticktock in Oz, as shrill as a dentist’s drill. My neighbor’s twin in pain? The man himself, moved down the hall too, so he can keep me awake? This time, laughing in helpless disbelief, I float away on it, the white noise of another man’s discomfort lapping round my head.

“Nothing by mouth,” the sign at the foot of my bed says in scribbled block letters, like a hasty judgment at last on the quality of my communication skills. It’s one more instruction, of course, about care and feeding, but despite that, I’m given the daily menu which lists grandiose sounding entrees for some, chicken broth, apple juice and jello for others. I’m headed for the clear liquid diet in a few days, and surprisingly in a rush to get there, since I can’t even begin to be considered for release until my digestion is up and running. Before 7 AM of my second morning, a polite and enthusiastic man stops at the bed to collect the menu. Apologetic but optimistic, he assures me that any day now he’ll be there to take my order. By the time “any day” comes round, “clear liquids only” has replaced my end-of-bed instructions, and Carlos, the food man whom I’ve gotten to know pretty well from his three times a day stop-bys to drop off or pick up menus, seems genuinely pleased to have me moving into his sphere. At lunch, he offers a grand flourish as he whisks the cover off my main course, a bowl of broth, then unveils a hunk of orange jello, my dessert. He wishes me “Bon Appétit,” and he means it, as proud of his presentation as if he were delivering at a four star restaurant. A sweet man, I think, images dancing in my head of the “poor Chinese baby,” who, lacking a spoon, struggled to discover the flavor of his wiggly jello, and Bill Cosby cooing to his enraptured TV audience about how there’s always room for J-E-L-L-O.

The theory seems to be that when you can eat, you can move – your digestive system, your foggy brain, finally your feet, all ready for essential action. This is beyond sitting up, or transfer from bed to a reclining chair, which happened early-on with a nurse’s persistence and my wife’s help. It’s about walking, the sooner the better –my ticket out. And now that I have full access to a gruel that would make Oliver Twist cringe, but which I’m pleased to call my own, I’m encouraged to try. Light headed and leaning hard on my wife while a nurse stands at the foot of my bed poised for emergency action should I stumble and fall, I begin with a small shuffle, imagining Fats Waller’s voice declaring “Come on and walk that thing! Oh I never heard of such walkin’! Mercy!”

My first effort gets me out the room door and to the nurse’s station down the hall, clutching at the seams of my absurd gown in a futile effort to maintain some dignity, my IV drip wheeling along beside me, my urine bag flapping against my leg. In seconds that feel like minutes I’m back in my reclining chair, worn out and sweating, leaking fluid from under my bandages where a drain has pulled loose, and from the edges of my Foley catheter and a partially detached bag of saline solution. I feel wet and swampy, an unwieldy boat stuck in a mucky stream. But it’s a start. Throughout the afternoon and the morning to follow, I float myself out into the stream of hospital traffic, marking my path with repeated trips. Right turn at the door, slow motion to the desks at the end of the hall where the nurses are chatting and collecting meds to give out to the residents of the surgical recovery wing, circling to the other side of the hallway and back to my dock, leaning hard against my wife’s steadying and steering arm.

Trying to be chipper, visibly earnest, well behaved and full of unquenchable optimism, I feel instead like a visible voyeur, aimlessly peeping into rooms as I drift by on my way up the hall to health. In each I see versions of myself, exhausted and probably worried men and women too weary to read the magazines, newspapers, books their friends have brought, too tired or drugged to manage more than staring out a window, or channel-flicking through the day’s infomercials or soap operas. But I’m ahead of the game, worthy of ridiculous pride and praise, up and about and not climbing back into bed until I’ve shown the staff and myself that I have enough get up and go to be up and gone.

Fats Domino forever has his walkin’(“yes, indeed”); Nancy Sinatra has her boots made for walking “all over you”; and I have my non-skid hospital slipper socks. By the third day, I’m able to get from C wing all the way into B wing and back. I ache everywhere with it, and sometimes need to stop to breathe; but getting out is a powerful motivator, and by the end of the day I’m told that “if everything still looks good” I should be back by the river tomorrow. I’m more dependent on my wife and nurses for encouragement, energy, support for all simple tasks, than I can bring myself to face. But the idea of home has taken on huge proportions and every hour I stay in the hospital makes me more fretful and peevish. Home, I think, is the place where I can look out at the sun and water surrounded by my things – feet up on the blue couch, Paul Simon or Rostropovich on the stereo, Dickens or Tin Tin in my lap – anything’s possible in the right space and place.

Here are the hospital exit questions. Get them wrong and you’re going nowhere: Are you running a fever? Can you keep food down? Any unmanageable pain? Ten on a ten scale? All frowny faces? Any bleeding? Any discharge or red streaking around the incision? Can you pass gas? No need for bowel movements, just plain old American gas indicating digestion in process. This one is make or break, and while modesty suggests restraint, necessity demands rudeness. If you can fart you can fly. And late in the evening before my possible departure date, my body rewards me with everything I need for a ticket of leave.

Trying to dress for the world out there, I discover that in four days my pants have ceased to fit. Swollen from the insult of the surgery, and gauze-packed from belly button to groin, I can barely pull up my chinos. With a loose shirt over me, I just leave the zipper and button alone. Bending to tie my shoes is out of the question, but my wife laughingly tells me to relax into helplessness while she wrestles on my gold toe crew socks and slips my sneakers over them. I try for nonchalance but physical dependency is a hard swallow. “It’ll be better,” my wife says, “just flow like a river.”

The metaphor is soft, but the drive home is hard, full of bumps and bounces that I’ve never noticed before. “Oh for cripes sake, the car’s not that old,” I complain to my wife, “what ever happened to the shocks?” Though my wife’s driving with exquisite care, each jerk and jolt says hold on tight, steady yourself, you’re not who you thought you were.

Finally, as if returning after a long trip, we turn up toward the house, familiar yet suddenly surprising. I push myself out of the car, slowly. And up the stairs to the second floor, slowly. Into the queen sized bed with its extra firm mattress, so high off the floor that it hurts to climb in. Weary, worried, but home to heal at last, dragging along my stiches and aches, my urine tube, catheter bag, hydrocodone tablets, unsettling memories of the hospital, and Dr. R’s emergency number, I slip off to sleep as my wife shuts the blinds. So this, I think, is my new beginning.

The initial changes are not subtle. Though some only last weeks, some hang on for months or more. Some, it seems will be forever. I learn to sleep on my back to accommodate the large urine drainage bag I’ve come to think of as my new-age piss pot. It sits squat in a large green plastic bucket on the floor to my right. Sometimes the tube that feeds it gets tangled or pulls loose, making a mess that my wife has to clean up since I’m still unable to bend to below waist height. During the day, where I go, my bucket goes, as if I’m constantly looking around for a floor to wash; have bucket will travel. I remember once hearing Odetta sing “there’s a hole in the bucket, dear Liza, dear Liza” and I suppose I should be grateful that this one is whole. But these days I feel Sisyphean, bound to the thing with no end in sight. If I want, there’s another way, a small bag that ties to my upper thigh – my dress bag. But as I’m rarely out and about these days, and the bag is unstable – leaking onto my pants leg rather than into the wash bucket, and needing to be changed often, it’s usually put aside for a “special occasion.”

“Oh, there’ll be some dripping for awhile, don’t let it bother you; it usually passes, ” the hospital resident who gave me my discharge papers had told me, as if I’ve become a faucet that needs tightening. But when the catheter comes out after three full weeks in place to allow the bladder to heal, I present a flood not a slow leak. And like the overflow of the Mohawk in springtime, there’s no controlling it.

“Do your Kegels,” Dr. R tells me when I call in a near panic at the addition to my pile up of pain and indignity. He means the pelvic squeezing exercises common to pregnant women and the rapidly aging of any gender. I might as well try to stop a runaway express train by holding out a raised arm or by simply willing it to slow down. “Be patient,” he tells me. And in the meanwhile, get yourself some pads.”

They come in all sizes, these dams of human effluence. I shopped for them when my mother’s dementia stole her independence and I know the drill, from Super Plus Absorbency to Light Day Ultra Thins, but I’ve never thought of them for myself. It means new larger underwear to accommodate the bulk; a new intimate relationship with the vagaries of what I’ve begun to think of as the time bomb that is my body; and a new fretfulness at the prospect of potty re-training. Depending on my Depends and trying to stay as empty as possible so as not to overwhelm their wick away capacities, I sit through hours at home that became days, then weeks, usually with a book in my hand, but mostly staring out at the river world beyond our house in a kind of trance- like waiting.

Friends phone and stop by, bringing news of ordinary doings from “out there.” But as nothing stops comfortable conversation like the feeling of the body emptying while visitors sit by unaware of the secret interior drama, and nothing disrupts congeniality like sudden and frequent trips to the nearest toilet to change urine soaked pads, it’s always a relief to regain the quiet of the empty house and the river beyond it.

“A half a day’s journey from the Colonie, on the Mohawk River, there lies the most beautiful land that the eye of man ever beheld,” Arendt Van Curler wrote in a 1643 real estate developer’s sort of letter to Killian Van Rensselaer in Holland. There used to be a marker of the spot he meant at one end of Schenectady’s downtown river bridge to Scotia. Two centuries later, the river was still flowing sweetly in the local imagination, celebrated in the sentimental ballad of “Bonny Eloise, / The belle of the Mohawk vale.” “Oh sweet is the vale,” the song goes, “where the Mohawk gently glides / On, its clear winding way to the sea, / And dearer than all storied streams on the earth beside / Is the bright rolling river to me. ”

But the human history of the river is darker than that, cloudy and roiling enough to make me feel a bit like Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott as I sit by my window on the world contemplating health, an observer “sick of shadows” but fearing a reality that can “come upon” me as “a curse” of recognition of things as they are. The Mohawk that eases me into a mood of recovery with the promise of energy and change in its flux and flow, and stability in its often unbroken surfaces, can fool me with the mirror of its glassy impenetrability that hides entangling weeds, twisting currents, eddies downriver of where I sit.

The word itself discomforts. “Mohowaug,” the name Mohican Indians gave their enemies, “eaters of living creatures.” The Dutch made it “Mahakuaas”; our New England forefathers and mothers called them “Mohawks” conjuring up birds of prey, killers of the sky. And killing defined life along the river for hundreds of years.

Along its banks, Father Jogues was murdered and martyred, fingers burned and crushed, flesh cut from back and arms, head lopped off and displayed in plain view, his body thrown into the Mohawk. Here, as decade passed into decade, war passed into war – involving all river dwellers – French and English, Dutch and Palatine Settlers, Tories and Patriots; Huron, Seneca, Oneida, Mohegan and Mohawk. Slaughter in battles bloodied the Mohawk Valley – at Wolf Hollow, Oriskany, Mount’s Clearing, Fairfield, Stone Arabia, Beukendaal, Klock’s Field, Herkimer. It’s one of the first things you learn about the place. At what used to be the North Gate of the stockade in downtown Schenectady, a sign marks the massacre of 1690, when, in the hard February cold of 1690, two French lieutenants with the sweet civilized sounding names of Le Moyne de Saine-Helene and Daillebout de Montet, and the Mohawk Chief Kryn, led a force of nearly 200 into a sleeping town, burning the city to the ground, scalping families, old and young.

Sir William Johnson, Joseph Brant, John and Walter Butler and their destroying Rangers, mythic heroes and bogey men to frighten children, left their shaping marks on memory and imagination along the killing grounds of the river’s fields and flood plains. Destruction followed the water, yet renewal did as well – the making of forts, farms, outposts and villages, cities, leading finally to houses like the one I’m sitting in.

The river shaped the places built alongside it even as it offered the promise and vision of next places. Bateaux and Durham boats, eventually Erie Canal barges and packet-boats, carried goods and people east to the heart of commerce, and through the Appalachian Plateau to the unknown continent beyond.

This river mattered , as all rivers matter, because it moved people, things, stories, along its currents. But the cost was high. By the early 1900s the river east of Utica was officially declared dead, victim of its many users and abusers – tanneries, factories, sawmills and gristmills, oil and chemical barges spilling into the water at canal transfer stations. The stink was potent until the last quarter of the last century, when New York’s Pure Waters Act sought to undo the disaster, enabling a natural recovery, bringing back the water I watch, as if newly made to wash my eyes each day as I settle in for viewing.

One morning our heron is back. He comes with the early summer fishing boat that parks from 5 to 7 a.m. each day near the wetlands below our house. Bird and man are both patient, waiting for underwater movement before flashing into motion. A few weeks after, snapping turtles, some nearly two feet in diameter, begin their long climb up the river bluffs, stumbling around in the scrub grass of our sandy back yard to find a place to lay their eggs, before falling back over the cliff edge to flip and tumble back to the water. Dozens of them, their hard work done, climb out on fallen tree trunks in the tidal pond to sun themselves. At night, red foxes tear up the nests, devour the eggs, but some hatchlings survive to reach the river and enter its protective flow. Red, green, and yellow canoes and kayaks begin to dot the waters. Silver crew-shells flash by in early morning and late afternoon. Grand lumbering cabin cruisers push slowly west and east, white caps ruffling in their wakes. Gulls circle, and now and again a red-tailed hawk or an eagle floats on a big wind, gliding high above the watery world.

That the river is finally unknowable and unconquerable is its saving grace, and my own. Moving outside me, it returns me to myself, reminding me of the mystery of my own flowing veins, arteries, the twists and turns of my life, always moving, even in what seem to be moments stalled in pain and diminishment. Months after diagnosis and surgery my wife and I walk together down to the river shore. By now the grass is head high, the ground spongy under foot. Kneeling, I put my hand in the cold flow, pull out a few stones ground smooth by the pressure of the water that embraces and then parts for my hand. I listen to the hush and surge of the water, hear the river’s voice from past to present. Hold steady, it says, for the wild ride to come.

Morning Shadows by the River

—Text by Harry Marten & Paintings by Ginit Marten

————-

Harry Marten has written a memoir (But That Didn’t Happen to You, XOXOX Press) and books on Conrad Aiken and Denise Levertov. His work has been published in The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post Book World, The Gettysburg Review, The Cortland Review, The Ohio Review, Agenda, Prairie Schooner, New England Review (and NER/BLQ when it was called that), The Centennial Review, Inertia Magazine, other magazines and journals. He taught at Union College, Schenectady, NY, for decades, retiring at the end of August, 2012. “Healing Waters” is part of a book-in-progress concerned with life along three rivers: the Mohawk (NY), the Ouse (UK), and the Corrib (Ireland).