Photographs: Jowita Bydlowska

Photographs: Jowita Bydlowska

.

We are half-drunk and the alcohol cracks us open, lets in some air. We’re not entirely relaxed but we’re better than we were when we left home, all stiff and silent, wedged into the opposite corners of the back seat of a cab.

Now, my husband says, “But if you had to? Five grand.”

“Okay, maybe the one with red hair. With the tattoo. But probably not,” I say. The one with the red hair with the tattoo is one of the three bartenders. The game is of what if. What if I had to sleep with a woman. For five grand.

I used to get crushes on girls in university. They all dressed better than me or seemed more comfortable than me in how they were in their bodies, their clothes—I wanted to be them and on rare occasion I wondered if I maybe wanted to be with them.

And I wanted to kiss Helen before, in high school. I would watch her plump, small mouth talk and talk and think of penises she sucked and I would get jealous. I wanted to kiss that mouth. I was curious. She drunkenly confronted me about it once, at a party, asked me in front of people if I wanted to make out. She said I was creeping her out with the way I stared at her. She laughed and I laughed along with her. I left the party as soon as she left to get another bottle vodka from the kitchen.

“Why not? She’s beautiful,” my husband says.

She is. I would kiss the redheaded bartender. I’d probably do it for five bucks or for free but I like lying to my husband, pretending to be hesitant about it.

I think he lies to me all the time. I have no proof but if you lie you think everybody else is.

There are other women here but the bartenders he can see best; they’re displayed right behind me. I wonder if my husband still sees me as beautiful. He never tells me I’m beautiful, any more.

His eyes never leave the girl display. “That would be incredibly hot.”

I say, “Your turn. Which one? The waiters.”

“They’re all men,” he says. “It’s different.” He finally looks back at me.

“Ten grand. Just a blow job.”

“No way,” he laughs.

“Fifteen.”

The patio is full, most of the tables occupied by couples similar to us, slightly crumpled stylish 30–40somethings. Perhaps they all play same stupid games. Perhaps, like us, they are parents set free for one night. If this is true, if you were to total the amount of money spent on tonight’s outing for this whole patio, it would be in thousands: outfits, sitters, cabs, dinners, booze, hotel reservations for some.

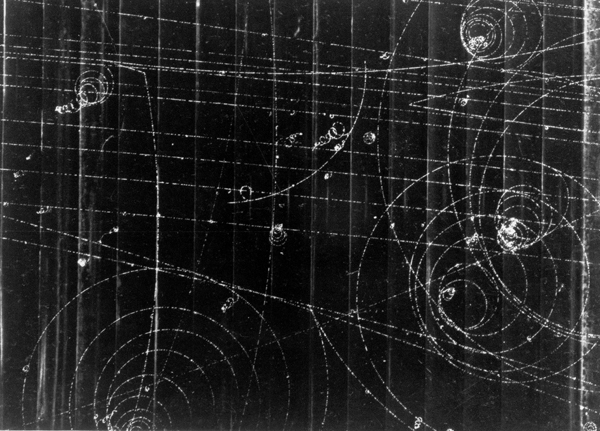

The restaurant itself is one of those places where car parts are used as decoration and drinks are served in mason jars with twine wrapped around them. Inside, the walls are exposed brick and air ducts under the ceiling and chandeliers made out of deer horns. Outside where we are, there are no special accents unless you count the waiters who all have moustaches and tattoos. It’s been like this for years now in Toronto, and there’s no sign of these sorts of trends going away. I try to imagine what the next trend will be, perhaps something to do with space, again like in the 80s but with some new twists: everything shaved off even eyebrows but armpit hair and it will be dyed; everyone will sit on the floor in restaurants, the walls will be empty and white, metal ceilings.

For now, this is one of the it restaurants downtown. You need double income to sit in these barbwire chairs without getting nervous about the injury and the prices, and you need high tolerance for hipness, which is why people like us eat in restaurants like this one. We’re not hip but we try to hang on to our youth. The way everyone does in their 30–40s. I don’t know if everyone else hates this shit secretly, like I do.

I share my observations with my husband.

“Yeah, if you’re right, we could probably live for a year on what’s being spent here tonight,” he says.

“Buy a nice car. Travel to China. I could travel to China where I would meet a man who’d murder me quietly in a dark alley somewhere.”

“You should try to go back to writing,” he says. “You always make things into stories.”

“It was a lame story anyway. You mocking me?”

“Yes, everything is a hidden insult.”

“I’m sorry. I thought you were mocking me.”

“No, I mean what I say. There’s no hidden agenda. You like to live in an imaginary world.”

“Not true,” I say even though it’s true. Despite the alcohol and the sudden ease it affords, I know I will never bring up how things are between us. I don’t know if he caught on that I’ve been fantasizing about leaving him. On some level, he must feel it—he must know that there’s something wrong, he must be aware of this ultrasonic scream that I scream. Then again, I’ve been pretending to be me for so many years that perhaps it is impossible for him to tell deception from the truth. The world he thinks he lives in, with me, is real to him but it’s something that I’ve created. He’s completely right about the imaginary world.

He sighs. “Fine. Not true.”

“Are we having a fight?”

“Of course not.” He laughs. “But do you remember when you thought I was this big playboy? You had this idea of me that had nothing to do with the truth?”

“You’re trying to have a fight.”

“No I’m not. I just always wonder why you need to make up these little dramatic scenarios. Life is quite interesting the way it is. Just write about penguins. You’d be great at writing childrens’ books.”

“I thought you were the novelist in the family. Anyway it was just a joke. About China, come on. Relax.”

“I’m relaxed. But think about the penguins,” he says and tries to ruffle my hair but I move back.

“Okay. I’m a bit testy tonight. You’re right,” I say when he grimaces.

I empty my glass of wine.

He says, “So has this thing with Helen and Rick been in works for some time?”

“No. It’s new. She just told me last week.” A lie.

“Did you know things were bad between them?” he says.

“Kind of. She wasn’t too happy. You know their baby issues.”

“The baby.”

“Rick doesn’t want a baby.”

He says, “Yeah, I always forget. I don’t think about babies. But there must be more to it. Divorce is a pretty drastic thing.”

I say, “Babies can be enough reason for women. I don’t know. Babies are a big deal.”

A moustachioed waiter brings us the next thing to eat. It’s broccolini; it slides on the plate in greasy sesame sauce and soya sauce as the waiter puts the dish on the table. The way the waiter describes it, he makes it sound like it’s a fancy gazebo. I can’t wait for him to go away. He does eventually.

I’m hungry so I scoop most of the thing onto my dinky plate and my husband looks on, “Glad you’ve got your appetite back.”

“What about my appetite?”

“You’re too skinny.”

“Like unfuckable?” I still care to be fuckable to him. Or I just care about being fuckable.

“You’re a skinny white mattress,” he laughs. “Just joking. I always want you.”

“I am what?” I say. I’m impressed with this joke. But it sounds like he thought about it a lot, like he just couldn’t wait to say it out loud. So now that he says it, I play the game where I will have to return the banter. I come up with something.

“A skinny white mattress. I could sleep on top of you and it would be pokey,” he says, “pokey, pokey, pokey.”

“I like heavy blankets.”

“Bam,” he says. He chews on his broccolini. “This is like eating an asshole. Like inside of an asshole. Like the asshole passage.”

“Ileum.”

“A what?”

“Small intestine. I read about it when I was looking up what my mother has been up to lately. She eats things that will pass through it undigested. It’s some new diet,” I say.

“Disgusting.”

“I like that she has hobbies now,” I say and the same waiter or one that looks just like him, with tattoos of words and symbols shows up with another dish. Some kind of shavings of meat like scraps of roadkill. Apparently a pork something.

“You have it,” I say to my husband after the waiter leaves.

“It’s not fattening,” he says.

“I know it isn’t. But you have it. I can’t eat pigs.”

“Why?”

Because I read an article about pigs being intelligent like dogs or even more intelligent. Because I watched a documentary about a slaughter house when I was 13 and had to cook for my mother and myself and I decided we should become vegetarian and she didn’t mind. I’ve never had bacon. The documentary, what I remember of it, was of pigs marching toward their death by taser and an ax to the tunes of Carmina Burata. It made me think of Holocaust. I told my husband the story a million times and he still doesn’t remember. He thinks this is about weight.

He eats the scraps as I gulp my glass of wine and motion for another.

I don’t know if it’s the same thing at other tables but when I look around, the other couples look as tired as I imagine we are. I picture them like us, in cabs, disgusted with their partners and horny because of wine, and resigned. Everyone wants to move the hell out of their lives.

I’m projecting. The proof is in a couple next to our table. The man reaches for the woman’s hand and she looks at him and it’s like a viagra commercial: her face beams with happiness.

“You think this is his secretary?” I say.

“It could be his wife,” my husband says, his voice low. I know he loves me more than I love him. It used to matter; now it doesn’t. He’s told me recently that he feels lonely. That ended up in sex; I had nothing else to console him with.

Another dish shows up and we split it; it’s a vegetable and at this point I don’t care what kind of vegetable; it’s marinated and so full of flavour that it shuts my mouth up. I count backwards from 20 then from 10 then from 20 again and order another glass of wine.

When we get home, we relieve the babysitter, my husband’s friend’s daughter with thick glasses and a 10-year-old blog. I read her blog to see if she ever writes about us; she never does. I can’t tell if I’m disappointed or not that we’re not important enough or not more important than the food she eats and writes about.

“You should check out Anhedonia,” I tell her. It’s the name of the restaurant that we just ate at. It’s a name too lazy even for a hipster lowball of being nonchalant.

“I have. My boyfriend is a waiter there.”

“Which one?” my husband asks as he hands her a stack of 20s.

“He’s got a beard.”

I’m in a satirical novel about intentionally funny dialogue, which is not funny; it’s trying too hard.

“Oh, him. Yeah, he was good,” my husband says as if he could identify the waiter.

“Mark. He’s got my name tatted on his forearm.”

“Yeah,” my husband says and winks at me. This makes me cringe but then I feel sorry for him immediately, for his inability to hide his age. I think about how we used to be a glamorous young couple at events, how there were no babysitters—the luxury of being able to pay for babysitters, too!—in our old lives and the biggest conundrum was which high heels to wear with what dress.

*

The last summer before Henry, we decided to become novelists. We would both finish books by the time summer was over and we would quit our boring jobs after publishing offers would start to roll in. My husband no longer took pleasure in attending launches of condos or multi-blade razors, and I kept bouncing from one administrative assistant gig to another.

The idea to become novelists came about after one of those TV shows about unusual jobs. Someone was a writer. He seemed to be doing really well. It was the first thing we both got excited about in months.

We rented a small cottage in the woods by a lake. We spent mornings writing, afternoons fucking, evenings watching movies; every night a movie from the convenience store in the small town where we got groceries. Movies about funny love coincidences, with blonde actress daughters of blonde actress mothers, or comedies; everyone with big twinkly eyes.

Somewhere in the middle of this idyll, I abandoned my novel. Or it abandoned me. When I read what I had written so far, it turned out to be just a string of words, characters complaining about other characters. No plot.

I did not tell my husband about it. To look busy, I wrote long emails to friends. To Helen mostly. Back then she was dating someone who had children. There was a lot of drama. I had to analyze things he’d say to her, give feedback. It was ever-absorbing.

For a short while I thought about using our emails in my story, see if a plot would evolve on its own, organically, out of the emails, but it didn’t. Helen and the guy kept not breaking up. They also weren’t having any breakthroughs. It was a slog of bitchy little arguments between them. Nothing else. Exactly like the characters in the book I abandoned already.

After writing and lunch, my husband would take his nap.

One afternoon, I read what he had written as he napped.

The plot was solid because the story had really happened. All he had to do was type it up and give people different names; call himself Mark, which he did, and write from third-person—now it was fiction.

I knew the story because he told me it when we first started dating. The thing was already few dozen pages-long and right away I could tell who it was about. It was a story of his ex-girlfriend who had disappeared. He had found her eventually but by then she was married and pregnant and she lived in a small town and she was fat although he didn’t write that.

I hated that the story was about the ex-girlfriend, not about me. The long descriptions of her body, elastic and light brown, and the way she made elaborate dinners for him, shaking her ass as she cooked—why was that still in his head seven years after he’d last seen her. Why wasn’t I?

The writing wasn’t bad.

I didn’t tell him I had read his novel and that I wasn’t writing mine. My disappointment was speechless with indignation. It wasn’t a novel, it was therapy, I wanted to say to him but instead I just kept that thought inside me

I thought of emailing Helen about this but it was too humiliating. I didn’t want her to think my life was imperfect too.

I started taking his sleeping pills in secret. I’d swallow them during our evening movie time. I’d be passed out by the time the movie would end.

He’d lead me drugged and mostly asleep to bed. Maybe he’d have sex with me maybe he wouldn’t; I didn’t care. I didn’t have to think of her brown elastic body that was in his head, when he would or wouldn’t fuck me.

That summer, I felt there was something different about me even before we came to the cottage but I ignored it. I was always very cavalier about my female body. I had no idea how many days passed between my cycles, I didn’t do self-exams of breasts. I didn’t take birth control pills because I didn’t even have a family doctor and I smoked.

In any case. We weren’t trying to have a baby. He’d always pull out of me and wipe me carefully afterwards. I never asked him why he was so paranoid about it but once when I turned over too quickly, he grabbed my shoulder and said, “What are you doing with your hand?”

He thought I was impregnating myself.

Ever since that time, I’d lie there like a cadaver, waiting for him to clean me up till he deemed me satisfactorily sperm-free.

But something got through. One little determined tadpole. And once at the cottage, it was the peacefulness of nature and the quiet that made me stop ignoring what I could feel already: cells multiplying, weakening me inside.

Out in the country, there were no honking cars around me, no sirens, no houses on fire. Just rustling of leaves, and at night, cicadas, frogs; a gold-wire sound of August insects in the grass during the day. All of that calmed me down; I was also slower because of the sleeping pills in my system. A nervous, whirring machine inside me stopped.

It was that quietness that made me pay attention, admit that there was a possibility inside me. I left early one morning to walk into the nearby town to a big grocery store, to buy a pregnancy test.

In the big grocery store, I locked myself in the bathroom and peed on a stick.

Not far where we rented our cottage, there was a farm. A big meadow where horses ran free and ate grass. After peeing on the sick and seeing two pink lines, I walked around the meadow, changed, no longer myself. There wasn’t just me now. There were two of me.

The horses didn’t come up but would look toward me occasionally. I felt spiritual in those moments, like I was connected to everything—the horses too, of course. “I am going to have a baby,” I told one of the horses and it looked at me uninterested.

*

My husband comes home smelling of cigarettes and beer. He says, “Helen was at the bar.”

“Oh.”

“She had an argument with Rick.”

“I should call her.”

“You should,” he says and stands there with his hands hanging against his sides.

In the past, he’d be sitting on the couch beside me, trying to kiss me, grope my breasts. But my body no longer invites it. And he tries very little to break through it. Mostly in bed. And even then, only if I turn a certain way. Often only if we both drink, our bodies come together under questionable consent according to the magazine articles.

“How was she? Was she okay?”

“She was fine. I walked her home.”

“That’s sweet of you,” I say. “Come here.”

He walks up to me then and bends down, stiffly.

He kisses my forehead with his lips.

Up close I think how he smells kissed-already. I picture a blonde 20-something-year-old throwing her thin arms around him, his baldness cute to her, manly. His body is a body of a former athlete. Women like him.

It arouses me to imagine this some girl kissing him and I pull him down by the neck and kiss him too, kiss him properly.

His mouth is surprised but only for a flash.

We stumble upstairs.

My orgasm is easy, fast. A build-up orgasm.

He pulls out of me and before he comes I angle my body so that it won’t land anywhere on me. The wetness grazes my shoulder. I picture the box of Kleenex on the night table on his side.

*

I told him after at the end of that summer that I would leave him if he were to try to publish it.

At the end of that summer, my body too was brown—brown like the body of the girl in his book—and smelling of sun. My hair went blonde from all the walks on the hot beaches. I was tall and gorgeous like a swimsuit model. A girl you marry so that others won’t fuck her.

I stood in front of him, with that body, in a swimming suit with my hair like that and I gave him an ultimatum. He was immortalizing someone else not me. The novel was not a love letter to me. He married me but it didn’t matter, all that sun and the body wouldn’t matter if he were to publish the novel.

And he said, “Then you have to leave.”

I didn’t believe he was truly a writer like that, that he really meant it. His stance surprised me.

Later on I thought that it was maybe his independence that he was standing up for. We were both blending in with each other as people tend to do in relationships, and he was fighting it.

We flew home on the same plane, different seats, without speaking.

I started looking for apartments.

He started reading and revising what he had written. He cursed in his office, “shit shit,” as he read it; I could hear him groan at night.

I heard him joke on the phone to someone telling this someone he would pay a dominatrix to not degrade him sexually but instead to insult his intellect, his creativity, to tell him how bad the writing was because he could no longer tell if it was as bad as he suspected. He wanted to destroy it but somebody else had to tell him to do that. It has to be a stranger, he said to the person on the phone.

Eventually, there was silence, no more cursing late at night.

I felt as if I’d won and it felt terrible. It felt as if I killed him in some small way. Now, desperately, I wanted him to go back to the manuscript. I couldn’t tell him that.

I found an apartment and put a deposit on it. I couldn’t imagine myself living on my own but here I was, about to do it. I had a vague idea about having to get a crib, set up a space for the baby-to-be. But I felt no enthusiasm about it.

I waited for my husband to tell me not to leave but he never did.

He took on extra shifts, wrote copy for magazines about dick products and shitty cars.

He would come home late and not check on me in the guest room where I lived now. We didn’t speak to each other, more than it was necessary: “Have you seen my umbrella?” “Rick is coming over.” “Helen called.”

I began packing. My plan was to do it loudly, obnoxiously, but he was never home. I cried but only out of frustration of nobody witnessing my misery.

After he’d go to bed I read what he had written so far. I read it again.

It was even better than what I’d read before. The writing was sharp, disciplined. The parts about the girl were tender but nothing over the top. Just simple words describing the protagonist’s desire and madness and self-loathing passages about loss: He felt offended by the world—it had the nerve to go on despite him being dead in it.

“You have to go back to it,” I told him, finally breaking our silence.

He was working late that night and I waited for him and he came home and I said that to him. It was almost midnight.

“You have to.”

“Have you found a place to live?” He asked without looking at me and his voice broke.

“Yes,” I said and we stared at each other and then we were kissing and it felt as if I could finally breathe.

“It’s so good,” I said, “your book, it’s so good.”

“I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Please.”

“If you want us to work out we can’t talk about it any more.”

“It’s so good.”

“Please. Stop.”

“I’m pregnant,” I said.

“Oh,” he said. “Good.”

And that was all. Good. He said nothing else about it then and we made love and fell asleep wrapped around each other, his hand on my belly.

*

The pictures online show a small house, a lake, a small beach. Another year, another vacation.

Inside the cottage, there are chairs, bookshelves, old comfortable couches. A large TV to watch DVDs on.

I move the cursor over the pictures. In some of them the lake is almost black against the washed out blue of the sky. The beach is all pebbles. There are Spectacular Sunsets!! advertised in the posting. A deck so you can look at our Spectacular Sunsets!!!!

The sunsets. And after the sunsets end, and the sky turns darker and after little Henry goes to bed, a deck to sit on, with a glass of wine, thinking up stories: me stories about penguins, my husband stories about former girlfriends.

Later on, we can make love by the Working Fireplace!!!

But first, before we do all that, I need to find his manuscript.

It will be like breaking a spell, finding this manuscript, having him go back to it

It will break the spell between us.

I don’t know what exactly I mean by that. I don’t believe in magic. But I suppose I do now: I have been reading horoscopes and articles about relationships on-line and I’ve played Solitaire obsessively like it’s an Oracle; playing till I win because I need positive answers to everything: Should I stay, should I go?

Yes, I still want to leave but I always come back; I place bets but the answer never comes—I’m always betraying myself in the end, even if I make a decision. I’m driven by chaos, not logic, emotions, not intentions. So perhaps the only thing left is magic, spells, breaking spells.

I go into my husband’s office to find the manuscript.

I’ve looked in the basement already but there’s nothing there, just crates of tax returns, hammers and rubber boots. No manuscript.

In his office, there’s nothing in the file cabinets, nothing on the shelves in the banker boxes. Lots of papers but none of them are the manuscript.

Perhaps he destroyed it.

I even look in a wooden box full of pens, hole punchers, staplers, magnifiers, a mirror with tiny grits of wet cocaine powder stuck in the scratches. Because maybe on the bottom.

Not on the bottom. Instead, I find a hotel key card, but not from the hotel we went to.

Once I find the key card, I become a detective, determined to find more evidence of whatever I think I’m about to discover. The manuscript is no longer important; the key card is.

I look behind the ship in the bottle. I don’t know why I look there. Maybe because I notice that the photograph of me pregnant is gone; it used to be right there, next to the ship.

How does this happen in movies? What is the buildup?

I try to recall specific movies, specific scenes, actresses, too, but I can’t; it seems there are so many—scenes of female characters going through drawers like me—through the pockets of her husband’s jackets, and the laundry. Kate Winslets, Michelle Pfeiffers, Cate Blanchets looking looking. Lipstick smudges on collars. No suspicion until the moment and it’s always a surprise, a hand to the mouth, a close-up on shocked eyes.

I see myself as if in a movie when I finally come across the item that confirms what I didn’t know but what I was looking for.

It’s tucked in behind the ship in a bottle. Not the photograph of me pregnant. A note.

I hold it in my fingers. I don’t have to unfold it. I can just stick it back where I found it.

I unfold it.

It reads: Can’t wait to fuck you again.

Then two hearts. A face with tongue sticking out.

The note is teenager-like but there’s carefulness even to the multiple exclamation marks that gives away this pretender. The writing is familiar, instantly familiar, actually; it’s Helen’s writing.

I have a quick, physical reaction to my discovery, a funny taste in my mouth, metal. Then, like a swift electric zap, desire to self-harm, too. To scratch my skin or smash my head against the wall. My body lunges forward inside me but I don’t move my body.

I wait.

I get up and go downstairs to the kitchen where I drink a glass of water.

I drink the glass of water; the desire to self-harm passes.

It’s getting dark outside. My husband and my son are at the museum looking at dinosaur bones. They will be home soon.

I drink another glass of water. Two glasses.

I walk up the stairs and go into his office.

I stick the note back behind the ship in a bottle.

I don’t know why I do this, like I’m not going to confront him about it but maybe I’m not—I can’t even tell.

All I feel is deep cold inside me, like everything is freezing. Like I’m freezing. The world is not the world. It is a movie. Maybe this is what betrayal feels like. Unreal. Unbelievable. Impossible to absorb.

There’s noise outside the door. My son shouting something. Boots stomping.

When I open the door, my husband shoves a bouquet of flowers in my face and then pulls me close to smash my mouth against his.

Henry is squealing, trying to pretend-push us apart.

It’s impossible. It was a joke. Some leftover thing from a party, maybe we played Charades, maybe Cards Against Humanity, maybe it was some sort of dare…

The was a party like that at someone’s house, last year. Songs. Charades.

I had to do “Love will tear us apart,” and I emoted—arms flying open from my heart, pretending to tear my hair out next, him watching and smiling, unsure.

It was hot outside, the windows were open, letting in the sticky, moist air.

We took a break from games and someone brought out cocaine. It was clumping from the humidity so everyone shouted, “hurry, hurry.” We cut it on a big butcher’s table and snorted big cloying lines and went back to Charades.

That was the last time we played. Helen and Rick were there but I don’t remember any notes, nothing like that, there were no games that would produce notes like that, everyone just talked fast, and later we couldn’t fall asleep, although we must’ve fallen asleep eventually.

But if the note is a leftover thing, a jokey thing why hang on to it, why hide it?

As we kiss now, my tongue becomes a feeler, trying to feel out this secret, the wetness of his tongue not telling.

His mouth smells of mint and cream. I lick the corners of his mouth to figure out the taste. Some kind of dessert.

There was the card key, too, from a hotel.

He makes a sound, a muffled growl. I kiss him deeper, licking now and biting. It’s like an athletic endeavour almost, this kiss, me tonguing, tonguing. Kissing like I’m buying myself more time to figure out what I need to figure out.

“So so so gross,” Henry says and walks away, his shoulders drawn forward, feet stomping in a performance of exaggerated annoyance.

My husband breaks the kiss and laughs, “Whoa!” His face is red.

Perhaps this is good. The note. Perhaps it will make things easier, maybe this will be the thing that will put me over the edge. This is a substantial thing, a thing people commit murder over. Infidelity. My best friend. How could he?

I’m an actress with tragic eyes; I should run to the basement and grab all the things and burn them in the backyard.

*

Rick answers the phone right away, “Nina.”

“Can we meet?” I hold my breath.

“Sure.” He laughs. It’s not nice laughter. But this is especially not nice laughter. It’s nasty. It’s laughter that knows why I’m calling.

I want to shout at him, tell him—what? Him knowing why I’m calling, laughing like that makes things easier for me.

“When can you meet? Can you meet today?” I say. I try to keep my voice as straight as I can. A line of a voice, a strong line. No wavering. Fuck him.

“Sure, let’s meet.”

I show up at their house.

He’s wearing a middle-age-crisis jacket, kooky patterns, too much red. He seems to be on his way out, “Hey,” he says.

“Can I come in?”

“No. Let’s go,” he shakes his head and I don’t ask where but follow him instead.

He drives without speaking.

The silence is uncomfortable. I find it arousing too. The same repulsion-attraction I’d felt when he licked my ear that time when we played Charades and he was supposed to whisper a word in my ear.

We check into a small boutique hotel converted from an old rooming house. The concierge is a young Indian guy who checks me out. He’s unusually attractive with wide features—wide nose, lips—and I wish I was going with him.

“Coming?” Rick says. The concierge gives me a small smile.

Inside the room, the walls are raw bricks. They make hotels out of old asylums, doll or glycerine factories, remove all the innards and stuff them with slick sculptures and beds with sheets and quirky art on walls. Blown-up photos of female body parts in black and white.

We are silent.

I sit on the bed, under a photograph of a shaved armpit.

He goes to the bathroom and stays there for too long.

I take my coat off.

I fluff my hair. I need to wash my hair. I haven’t washed my hair in a while. It doesn’t matter.

He comes out, his face red, shining with wetness.

He sits in a chair across the room.

He watches me sitting on the bed.

Outside, there’s a courtyard, an old van with an airbrushed mermaid parked in it. Garbage bins and garbage bags. A tree with sparse, sickly leaves—a tree that wants to die and can’t.

“What are we doing here?” I say.

“We’re here because our spouses are shitty human beings and we are going to get revenge by fucking like crazy,” he says.

“Is that a good idea?”

“Why are you here?”

“Because I thought it might be a good idea.”

“There you go,” he says but doesn’t make any move.

I say, “When did you find out?”

“I paid someone. To follow her. Like they do it in movies,” he said. “I have pictures. I can get into her texts. It was almost fun. I felt like a kid detective. Nancy fucking Drew.”

“You actually paid someone.”

“Yeah. I can’t just spend my days spying on her. I was worried I’d hurt her, too,” he laughs. The laugh is short, fake. “I thought it was this little douchebag from her workplace. I wanted to see pictures of him, of them together. But then surprise!”

“Surprise.”

We fall silent again.

I look out the window. A man gets in the mermaid van. He doesn’t start the car. I wonder if he’s a detective too.

“Well I’ve always wanted you,” he says.

“That’s natural. Proximity.”

“Maybe.”

I say, “I should be angry. But I’m only doing what I think I should be doing, calling you. I don’t feel angry.”

“You’re trying to convince yourself you don’t feel angry,” he says.

“I love him.”

“I’m sorry,” Rick says. He gets up. He comes up to me and wipes under my eyes with his thumb.

He bends down to kiss me. His kiss is soft, softer that I would’ve expected from a mouth that says so many idiotic things. I kiss him back, take a clue from his softness, make my mouth pliable, submissive.

I wait for a bite but it never comes.

When he pulls away I let out a sigh. To him it probably sounds like desire.

But it is desire, too. It’s despair and desire.

He undresses me quickly, and I undress him.

We don’t spend much time on foreplay.

Our coupling is dry and fast. It’s unpleasant for a moment but then my body takes over, overcomes the initial discomfort: it lubricates.

Rick breathes rapidly, and I start to breathe rapidly too and I move along with his rhythm, close my eyes and let it take me away.

I can feel his rage, how it makes him hard.

He kisses me again and this time he bites.

I bite him back.

“Dammit,” he shouts. He touches his lip, looks at his fingers. No blood. “Dammit.”

He goes at me, faster now, to punish me, perhaps. He groans like an animal. He sweats a lot. Our bodies slick and slide. I adjust to this new rhythm quickly and I groan, too. A fucking panther. Fucking. We’re a sex zoo.

I feel the warmth: contract, pulse, squeeze.

I pull him even deeper inside me.

I clutch onto him, I love you, I think, feeling my orgasm fire off inside me.

After he collapses on top of me, I push him over.

He goes to sleep.

I lie with my eyes open.

I fall asleep briefly into a quick, satisfying dream. I dream of being made love to by a short, old man. Nobody I know. He holds my legs down as he kneels above me. We are both amused by how flexible I am, by how my open thighs touch the ground completely flattened out as he thrusts.

When I open my eyes, Rick is in the shower. I put my clothes back on and leave the room.

I walk through the underground shopping maze to get to the subway. When Henry was born, I used to come here all the time with the stroller. It was one of the places that opened very early. Like most new mothers I needed to have all kinds of stupid things to do before noon in order to prevent dying of boredom and guilt from not loving my child enough.

My favourite store was a large bookstore with bright lights inside.

I would go in and read all the magazines I would never buy. Tabloids and magazines about how to parent, or repair bicycles, and magazines targeted to lesbians, and music magazines.

There was a condo building above the shopping maze that was nicknamed “The Menopause Manor” because it was mostly occupied by the elderly. They, like the stroller-pushers, would come out first thing in the morning. They would buy expensive coffees and English muffins and eat them while in the little food court by the bookstore, watching everyone who wasn’t them. People like me, the young.

If I would sit down, there would suddenly be two or even three women with trembling white hair and lip-smacking fuchsia mouth, cooing at the baby, looking up at me with what I read as a plea: Get me out of here. But the “here” was age and we were all going that way. I wanted to shout that at them, tell them to leave my child alone.

Later, I softened. I thought of how carefully they dressed to display themselves to the world, to prove that there was nothing wrong, no loneliness, no death.

I recalled reading about sick animals, how often you couldn’t tell they were sick because they would present themselves as healthy—the outward appearance was a defence against a world that is ruthless in discarding its weak.

As Henry grew, I would take him back to the shopping mall and we would sit down and wait for the first cloud-haired lady and we would tell her what Henry’s name was and what he liked to do the most—art— and was he good to his mummy, yes, he was.

I felt like I was being charitable.

Today is the first time since long ago that I walk through the mall.

The bookstore is bright and shouty with front-store shelves displaying the latest hits: books on gluten, gardening, how to overcome being an asshole.

The elderly are occupying every table in the small food court by the coffee shops.

A stooped man in a t-shirt that reads “pushing 95 is enough exercise for me” stands at a table occupied by a flock of white-haired ladies. He says things that make them laugh.

He looks at me and winks and I wink back, without thinking.

I try to imagine who he was—I try to imagine him as my sexual counterpart.

As him, he is tall and his eyes are bright blue, not cloudy, and he has wide shoulders and wiry, black hair on his strong chest; he is a rugby player, a guy who drinks and fucks and laughs on yachts.

I think how that guy is trapped inside this twisted body, how there’s no getting out, how his desire must learn to die but it is refusing to die. The desire drives him, it tells jokes to ladies, the way it used to; it is a wink, a lighthouse in the darkness: I am still here.

I cannot get on the subway yet. There’s too much time between now and later. The house is empty. That note.

I need a distraction.

I worry that in the empty house, I will behave badly, look through old photos, go on the Internet and do quizzes. I will compose emails to Helen or to a relationship advice columnist and I will never send them.

Many of the elderly look up when I halt in the middle of my walk. Sharp eyes. Anticipation. Maybe I will start screaming, fall down. A woman alone, disheveled.

There’s a movie theatre on the main floor of this place and I turn around, decide to go see a movie. A movie that will make me not think for a few hours, any movie will do.

I pick a movie about people in space. Three-D glasses.

The people’s space shuttle gets blown to pieces by cosmic debris and there are only two survivors.

They float in space to try to get to other shuttles to get back to the earth. It doesn’t work out for the guy; he floats off to his death. She survives somehow; it is a movie after all. There are dozens of scenes where she almost doesn’t survive. Almost dies all the time.

—Jowita Bydlowska, Photos & Text

,

Jowita Bydlowska is a writer and photographer living in Toronto. Her first book, Drunk Mom, was a national bestseller. Her novel, Guy, was published in 2017. Her short story “Funny Hat,” published on Numéro Cinq, was selected for the 2017 edition of Best Canadian Stories. You can view more of her photographs at Boredom Repellent.

..

.

Editor-in-chief prepares to leave the building.

Editor-in-chief prepares to leave the building.

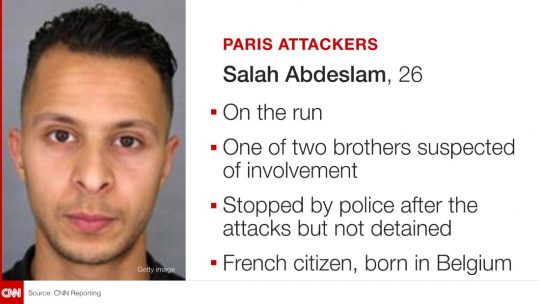

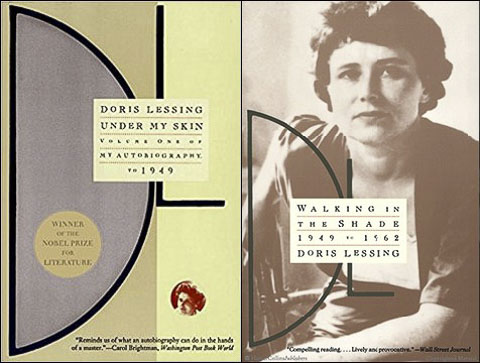

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature

Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh

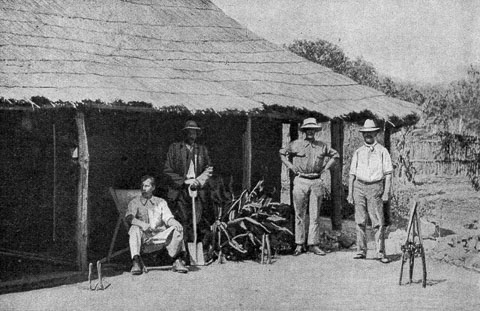

Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons

Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons Lessing with her mother and brother

Lessing with her mother and brother Doris Lessing, age 14

Doris Lessing, age 14 Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons

Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via

Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via  x

x

T. S. Eliot in 1923

T. S. Eliot in 1923 Young Tom Eliot

Young Tom Eliot

Mark Twain in 1882, two years before publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain in 1882, two years before publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Eads Bridge, St. Louis, Missouri, between 1873-1909, courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collection

Eads Bridge, St. Louis, Missouri, between 1873-1909, courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collection Twain with his family around the time Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published

Twain with his family around the time Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Tom, Jim, and Huck — Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Tom, Jim, and Huck — Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Josh Dorman in his NYC studio

Josh Dorman in his NYC studio Camel Cliffs – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 12 x 14 inches, 2009

Camel Cliffs – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 12 x 14 inches, 2009 Knight Errant – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel,

Knight Errant – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016

Tower of Babel (for Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman) – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 48 x 38 inches, 2016 Night Apparitions – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel,

Night Apparitions – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, Welcome to the Machine II – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, with resin, 12 x 12 inches, 2017

Welcome to the Machine II – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, with resin, 12 x 12 inches, 2017 Wheels – graphite with antique collage elements, 10 x 20 inches, 2017

Wheels – graphite with antique collage elements, 10 x 20 inches, 2017 Thelma, Memory Bridge portrait – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 34 x 42 inches, 2006

Thelma, Memory Bridge portrait – ink, acrylic, antique paper on panel, 34 x 42 inches, 2006

The Red Queen and the Red King in

The Red Queen and the Red King in

Luna Park by Marc Shanker

Luna Park by Marc Shanker Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross

Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird

Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan

Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines

Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw

Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj

Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj