.

February 23, 1991

.

You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

What on earth is Eliot talking about? I should know: I’m an English teacher. But that doesn’t mean anything. I should know that, too.

It is Saturday morning, early, or early for me. I’m sitting by the garden, our garden on a hill that overlooks South Bay, reading his Four Quartets. On the bench beside me, coffee, a radio. Every now and then I turn the radio on to catch the news.

I’m reading the Quartets the way I have always read them, in fits, bits and pieces here and there, skipping around. I’ve read the whole work over the years, but have never read it all the way through in one effort, and I only know it as so many fragments. Burnt Norton, East Coker, The Dry Salvages, Little Gidding—I can at least put the poems in order, but if there’s any order to that order, it has escaped me. All the shifts in voice, the abstractions, the faint symbols, the ghosts of allusions—the thing tries your patience. It’s not a poem I would try to teach, if poetry were what I still taught. I don’t even remember our spending much time on it back in grad school. Still, I come back to it. There’s a meditative lilt to the sounds, to the rhythms that has stayed with me. It’s the closest I get to religion.

Today, however, Eliot irritates me. His words sound like chants of an old man trying to settle the uneasiness from a worried life, of the ache of brittle bones. I woke at six with a rush of purpose, full of resolve, only to realize there wasn’t anything I particularly had or wanted to do. Too much wine last night. I ended up here by default. It’s not the kind of thing I do, sit by a garden. It is not like me to sit still, and after an hour of sitting here, dipping into the Eliot, listening to the news, looking at the garden, I feel I have come to the end of something. No ecstasy—do I get points for that?

The news is not news. We have been bombing the shit out of the Iraqis for over a month. The deadline approaches for invasion, 9:00 here, noon in Washington, some other time in the Gulf, soon to pass. Rumors of last minute negotiations. Nothing will come of either. Bush won’t give this war up—he needs it. But he won’t commit troops as long as he can keep up the aerial attacks. And it has been a clean, pretty war for us, the U.S., from what we see on the tube. Vast stretches of desert sands, the floral splendor of night raids over Baghdad—the bombing will continue. We will keep bombing until there isn’t anything left. That way we maintain world order.

Our garden is not pretty; it is a disaster. We were hit by a hard freeze a few months ago, around Christmas, the worst in more years than I have been here. Everything is dead or looks dead. Dead plants on dirt—dead leaves, dead stalks, dead vines, dead buds of whatever it was that bloomed in winter—a brown mesh of deadness blending into darker shades of brown. Even the few plants Margaret had been holding out hope for it can now be safely said are safely dead. The only green has been the weeds, which she pulls as soon as she sees them.

After a light rain last night, the rich, bitter smell of decay.

Yet it is a beautiful day, shirtsleeves in February, another freak of California weather. Cloudless, smogless skies, the skies an unqualified blue. Not the transparent blue that threatens ethereal dissipation, but a blue soft and full, with unforced presence. The morning chill has already burned off and the warm air caresses without crowding, as if you belonged here, as if the world were a place where you could live without protection.

The bombing, dead plants in a garden—there is seeming correspondence. I will not be sucked into pathetic fallacy, however. Nature has its rules, we have our own, such as they are. One has nothing to do with the other. Only the sentimental would make something of the accident that has brought them together. And even if I tried, I can’t imagine what kind of causal link might be established or what could be made of the balm of this morning sun.

But back to the Eliot. I also feel vaguely guilty, or vaguely sense the need to feel guilty. Perhaps the poems will give my life this grace. And the poet has gone through a couple of wars himself. In fact he wrote these some time around the Big One. Maybe he can give me some pointers on how to do this war, or at least on how to sit it out.

In order to arrive there—

He is talking about a kind of humility, a kind of vigilance. His point, I think, is that if we’re ever to get closer to anything larger, anything beyond ourselves, we need to deny the self in some way, get outside the self in order to see the self and whatever might lie past it, presumably a whatever that is worth the trip. He is trying to get us closer to Something Else. The figure of travel is a metaphor for that desire. This is too mysterious, or too mysterious for a Saturday morning, too mysterious for a hangover.

Time present and time past—someday I should go through the whole poem, beginning to end, alpha to omega, soup to nuts, because I think there is a progression, an argument that unfolds, at the end, a conclusion to be reached, maybe an understanding, maybe, God forbid, a revelation. I suspect if I did, though, I would only be disappointed. One more literary nut shelled and digested. Better to keep the possibilities of ignorance alive. In the cracks of doubt, of the unknown, maybe a chance—

Margaret—

The English teacher’s wife—

Comes out with her coffee, sees me, and winces softly. Winces because though she’s an early riser, she wakes slowly, also because she did not expect to find me here, by the garden. Softly because that is how she would wince. Then packing her surprise, she lingers a second, composing the Margaret face, a face that respects the decorum of a working marriage, that recognizes that I exist, will continue to exist and have a right to continue to exist, that shows that, even though I have existed with her in civil matrimony for almost twenty-five years, she has not yet lost fondness for this existence nor will she take it for granted—but today a face that also says she does not want to come to me just yet. Fair enough. Instead, she walks over to the garden and stands there surveying the damage, arms folded, coffee cup poised above their cross, her cheeks furled before the winds of a dilemma, as if she is trying to decide what to do about it.

Margaret, not Madge, Marge, Margie, Maggie, Mag, or Meg—she made that clear at the outset, her only condition for marriage. A native Californian, there is such a thing, and some of them have some sense. Second wife. My first marriage was to English, while in grad school, which blew up before either of us had finished our dissertations. We both reached a critical mass of literature and frayed egos, of our exhilaration and desperation over criticism no one cares about, or should. Next a period of celibacy that I thought I chose but really just happened. Then Accounting. Not that Margaret is another convert to the faith of the business of business; that is just what she teaches. Every day, before meeting the hordes who have chosen her discipline as the light and the way, she dresses in a sober suit, before the mirror flounces her scarf to a calculated carelessness, then puts on the face, a face of businesslike compassion, that hybrid of concern and practicality that seized me when I first saw her standing before her class at State where we both still teach, the face she now wears before the garden, before the thought of me, a face that doesn’t fend off despair and disorder as evil or unnecessary but takes them as givens, matters not to be questioned but measured and arranged. Accounting is not a subject but a manner, a way of dealing with whatever life dishes out and finding it a place. Margaret is all manner and manners. I don’t think I could live without her.

Now she steps through the garden in a winding pattern, following some invisible map, still pondering. It is not fair to her that I pick this day to be out by the garden. Except for minor demolition on my part, it is all her work, and her work lies in ruin, ruin brought into relief by this bright, smiling sun. And given my ignorance about plants, she knows I don’t appreciate what has been lost.

I don’t understand much about what makes things grow and am perversely proud I do not. I do know, however, that a garden at best is a complicated problem. I know because she gives me quarterly reports, and now it has become an improbability. After three years of scant winter rain, last summer she shifted to drought resistant plants, but then these cannot stand the cold. And while it seldom freezes here, after last December and the deadness now, she now has to factor in that chance. But plants that can take a freeze need lots of water and are averse to too much light, yet it does not rain here in summer and we have little shade, so anything she puts in next has to be able to withstand a full season of sun—and until the drought lets up, another season of rationing. I take these contradictions as evidence that we really aren’t supposed to be here in California, any of us, though we have all gold-rushed here and overrun the place, straining the water supply, our dreams of a better life. Margaret does not think that way, however, about our intents or foolishness, or about the vagaries of the weather. She takes things as they come.

But I know she is not thinking about her plants. She has said she will wait until late spring to deal with them, when the rain stops, the weather settles, her classes are over and she has the time, and she always sticks to the Plan. What she is really doing is debating whether or not she wants to deal with me today. She has read my look and sized me up: she has seen that I have the desire to talk. Yet if she is bothered by me, by the garden, she does not show it.

I’m her second go around, too. I don’t know anything about her first. She never talks about him, I never ask. Not that she’s hiding anything. It’s just part of the decorum, I suspect. She won’t say anything about me, either, if we ever split up. I admire that in her.

Just the two of us. The girls have flown the coop.

She slides her foot through the dry waste, making static noise, then nudges a bush with her toe It does not spring back.

I try to get a rise out of her. I pick a passage at random and read aloud:

Do not let me hear

Of the wisdom of old men, but rather of their folly,

Their fear of fear and frenzy, their fear of possession,

Of belonging to another, or to others, or to God.

“What do you think of that?” the English teacher asks.

“Sounds like good advice.” She doesn’t turn, but bends over and tugs at the withered stalk of some unrecognizable plant. She still looks good in jeans.

No rest for the weary is what I think the poet means. I don’t think Margaret heard me. I try again.

“The war will start soon.”

No response. She does, however, succeed in pulling up the plant, and, holding it close to her face, examines the shriveled leaves.

“It will be a bloody mess. Body bags on the way.”

She taps the roots gently, shaking off the dirt.

“I’m thinking of enlisting.”

She throws the plant over the fence. My heart goes with it.

“I’m thinking of retiring.”

“Fine,” she says. With that, she mumbles something about breakfast and goes in. She knows I’m in one of those moods, that I want to start some endless conversation that will only result in my getting both of us upset. Margaret will not indulge me today.

She’s a good woman.

.

.

No word of war. High noon in Washington, the deadline has come and gone. The English teacher has succeeded only in rising to get a stack of papers to grade, which now rest on a bench by his chair, unmarked, unread. Students fear his judgment—they don’t know what a sweetheart he is—but he has decided to spare them another day. He is not up to seeing what they have done to words and still has a headache from his hangover to boot. So he’s just sitting by himself by a garden on a hill, a hill that overlooks the valley by the bay, the valley that is called Silicon Valley, the bay that is called the Bay. On his lap, a poem by T. S. Eliot; on top of the papers, more coffee, a radio.

Saddam lobbed another Scud missile at Israel a few minutes ago—that much is clear. And the reports that he has been setting oil wells on fire, hundreds of them, have been confirmed: smoke can be seen on the horizon. But the other reports are confusing. Negotiations have failed, they still continue. Our troops are rehearsing for assault, the invasion has been put on hold. Either Kuwaiti civilians have been rounded up, tortured, and executed—or they have not.

He has a tough job, the newscaster, casting the news, juggling what his reporters can scrounge up and what little the government lets him know with what he wants to tell me. And he has to find the pitch that prepares me for sudden drama yet won’t frustrate me with false anticipation if I have to wait—or if nothing happens. He does that very well. A poet, my newscaster. And he needs me, he wants me, he loves me, and does not want to let me down. For this I will never forgive him—

But I leave him on, just in case.

I don’t know how I got hooked on this war except that I watched it on the tube a few times from boredom, and then once I started, could not let it go. First the six o’ clock news, then the late night special reports to see if anything had changed. Then the car radio frozen on the news station, then this portable I carry to school, around the house. Much has been said, day to day, and there has been much to see, but all that I have heard and seen over the past months could be summed up in a few sentences. Still, I feel that if I ever stop following, if I step just once out of the flow of current events, I won’t be able to get back in it again. A continuity will be lost, and we’re running out of those. Besides, how are you going to know when the parade passes you by unless you watch it?

This quarter has not gone well. Listless students, flaccid prose, insincerity, incoherence. More dropouts. Ted, a colleague, thinks it’s the war, that it has depressed them. I doubt that. Their spirits have never been very high and they drop out all the time. It’s the dismal business at home that gets them down. If anything, the war is a good distraction. It gives them the illusion that something is being done somewhere about something. And perhaps it will stir up some jobs in Silicon Valley, now languishing at my feet. What really depresses them, I told him, is our making them write papers. Nonetheless, the school is sensitive to our students’ psychological states, and the Dean has recommended that we talk about the war in class to ease whatever tensions it may have caused. So I have been holding discussions:

Anybody bummed out about this war?

—Not really. Maybe. Are they supposed to be?

Why is Saddam Hussein there?

What are his interests?

Why are we there?

What are ours?

—Oil. The rest is fuzzy. Uneasiness in the class, though. They sense the teacher is trying to wrack their political souls, to exact from them a confession. I assure them I am not. It’s the young guys in the department, the guys with ideological hairs up their butts that have made them suspicious. They talk about empowerment, difference, and liberation. Really, it’s their way of telling students they’re unreformed boobs. I tell students I respect their freedom. I tell them lots of things.

Who is on our side?

Who is not?

Who is Saddam?

Who are we?

Where is Kuwait?

No one seems to know much of anything. More questions from the teacher: they have grown tired of them. I am tired of them myself. There is consensus among them, though, that Saddam Hussein is evil and should be taken out. At least here we have moral clarity. Bush has done his job.

Do they realize that if there is a ground war, it might be a long one, that they could be drafted and have to fight?

The guys are not concerned. Yet why should they be? Why would the government trust them with its complicated, expensive machines when it doesn’t trust them with anything else? Computers in the tanks, computers in the jets, computers in the foxholes—they’d only screw them up.

Why should anyone wrack their brains over this one? Someone will tell us what it all means later.

But then this is how to do it, stage a war. Dazzle us with technology, minimize our risk. Bomb, bomb, bomb. This way Bush maintains the symbol without spilling the substance of American blood. Because my students know what we all know, that he does not want to lose our hearts, much less our lives, because he wants us, he needs us, he loves us, too. He wants us to have a good night’s sleep. He wants to give our lives Meaning, to give us a word that does not mean Vietnam. And to show that he loves us, he has to put on a good show. Our generals pride themselves on their precision bombing, but if those bombs are so precise, why do they need so many? And the TV cameras they use with smart bombs aren’t for guidance but are part of the production. In the cross hairs, on the screen: city, block, building, roof, air shaft—boom! Boffo! We are amazed, we are fulfilled, we are head over heels in love.

No war today—too much is at stake.

The world is as thick as our skin.

But what to do?

Where’s my wife?

Margaret has not yet returned. She was busy at her desk when I went in to get the papers, or was busy looking busy and did not speak. She will come when she wants to come. There is still the aging poet to keep me company—but I have lost my place. I’ll start again, somewhere else. Which is the one with the garden? Today I’m in a mood to read about gardens.

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden.

Burnt Norton, first quartet, first page. I have some notes:

1936

Norton: manor house, Gloucestershire. Burned down, 17th. cent., rebuilt. TSE went to 1935 w. Emily Hale (wishes had married instead?)

You can’t read Eliot without notes. He visits a garden at some old house, or remembers visiting it, and takes off from there. Each of the Quartets is linked to a place that has some personal significance, which is what I think he is trying to do, locate himself in space and time. Not a bad idea—I’d like to know how that is done. Not a bad idea for Eliot in ’36, given the noise in Germany. Nothing else on Hale—I don’t know who she is—but at the bottom of the page, another note with an arrow pointing to rose, circled:

Rose: symbol sexual love/Divine Reality (Dante)

How can a rose be a symbol of both? I’ll have to get Margaret’s opinion on this. She has—had a dozen bushes in our little plot, though I doubt she saw blooms past the aphids and mildew. And before they had a chance to wilt, she lopped them off and threw them in the trash. I’ve never gotten around to Dante. I was an Americanist before I moved down into comp. Maybe tomorrow, maybe the next war.

Down the passage we did not take—who is with the narrator? Is he still hung up on Hale? Or is he trying to take us all along? The door we never opened—so do we open it now, or just imagine? Are we contemplating opportunities missed? Should we have married someone else? We all know better than that. Maybe we’re just trying to recoup from the mess we’ve made of our lives.

Other echoes

Inhabit the garden. Shall we follow?

Quick, said the bird, find them, find them,

Round the corner. Through the first gate,

Into our first world, shall we follow

The deception of the thrush?

What is this damn bird? No notes on the echoes, either, but we follow, or pretend following—what else is there for us to do? The door we never opened, the first world—is he talking Paradise here? Has he fallen? Have we fallen? Do we care? Or the first world might be something private, something personal—a chance he had but blew? A garden could be anything and suggests too much to pin down. Another Eliot ghost. But we follow and open the gate, or maybe we don’t, but somehow

There they were

He shifts to past tense—is that a memory? Yet since we never opened the gate, is it something we imagine might have happened? Anyway, somehow there they were, but we don’t know who they are, there they were in the garden, dignified yet invisible, saintly people they must have been—maybe it’s their echoes we heard, they must know something we do not, they must know Something Else—and the pace relents, and still we followed, now slowly, there they were, whoever they are, our guests he calls them, accepted and accepting, there they were, and they moved with us, in a formal pattern, but not as if in memory or imagination, but as if in a trance, in a dream—

Jesus, this stuff makes you dizzy. The old poet is so careful to be so confusing. Each time I read these lines, I feel I have never seen them before. They only recall from past readings echoes of vain attempts to figure them out. But this is not the wry Waste Land Eliot; I sense we are supposed to be lightly moved. And there is, I suppose, something lightly moving, moved lightly with the rhythms, with the sounds, with the scarless words. And there was, I suppose, a time when I could be thus lightly moved—

But we aren’t so stupid now. Yet we followed then and we follow now because we’re hungover and can’t think of anything else to do, we follow the movement in the figures of motion, of flowers, of sight, of patterns and light, whose delicate associations rise and connect in airy matrix, building scaffolds around what they reach for, try to construct, to contain, and still we followed, we follow, follow them along the empty alley, into the box circle, follow to the drained pool, where we stop, where we think we have a glimpse—

And the pool was filled with water out of sunlight,

And the lotos rose, quietly, quietly,

The surface glittered out of heart of light

Zen stuff here—the poet also listened to voices from the East—but a cloud passes, the pool is empty, and the moment, the light is gone.

Glimpse of what?

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Blue skies soft overhead, a poem on one’s lap, a freeze-dried garden, a newscaster’s pleasant voice, the news of war, a pounding in one’s head; a long, black ghoul, the shadow projected from a teacher sitting in a lounge chair on his deck: these things are real, and they’re as far as one can go. They’re also more than one can bear.

Glimpse of what?

The scaffolds collapse.

There’s no there there.

There’s nothing there but words.

More Eliot hocus-pocus.

I realize I know little about the poet’s life, save for some gossip, but then I make a point of not learning about authors’ lives. Let’s save our questions, our revenge for the living and unlettered. And it is the measured words, not a writer’s beliefs and other casual slips that deserve our attention. Today, however, I am curious. The poet has gotten under my skin. What else do I have? I flip to the front. Next to the title page, the epigraphs:

Heraclitus. I don’t know Greek, and only have scribbled a translation for the second:

The way up is the way down.

I have forgotten what that is about. Underneath the title, more notes:

T. S. E. 1888-1965

royalist in politics!

classicist in literature!!

Anglo-Catholic in religion?

anti-Semite????

At the end, Little Gidding, he makes some kind of one-for-all-and-all-for-one pitch for England, if I remember right. I must have written those notes in grad school, back when such things could surprise me, back when Modernists were still modern. I doubt Eliot is a hot item at Stanford now—but we all screw up sooner or later. Yet this is one fear I have about the Quartets, that for all their delicacy, their complexity, their diffuse suggestion, what they mask is very small.

My other fear is that Eliot wants to convert me.

A screech—

The patio door—

Margaret at last, love of my life, the yin to my yang. But she stands there in the opening and waits for me to speak—a bad sign. I hit her with this, con brio:

Garlic and sapphires in the mud

Clot the bedded axle-tree.

The trilling wire in the blood

Sings below inveterate scars

Appeasing long forgotten wars.

She stares at me. No games today.

“You’re not serious, are you.” She does not raise her voice at the end to make a question. She seldom does.

“No, never.”

“I mean about what you said.”

“What, about enlisting?”

“I mean about retiring.”

“Sure. Why not?”

“I don’t think you could stand it.”

“What is there to stand?”

“I don’t think you could stand yourself.”

Suddenness, maybe anger from Margaret—another bad sign.

She remains a moment, either giving me a chance to reply or trying to think of some way to mollify the abruptness of her remark. But neither of us finds anything to say. I make a mental note to fix the door. She takes a slow breath, releases a gentle heave. Then the door scrapes shut.

I read aloud to the door, its cry still scratching in my ears:

The dance along the artery

The circulation of the lymph

Are figured in the drift of stars

Nothing happens.

Couldn’t stand myself—not irony, not from Margaret. What has gotten into her? She must be in some kind of a funk. I suppose I should be careful with my sarcasm. Then again, she could tell me when she is going to take me literally. Something has started here. More later. Film at eleven.

But why should she be upset? She must know I wouldn’t do it. I’ve never really thought about it, yet now, for the first time, it occurs to me: I could. I’m not that old and don’t feel old. I can still go three sets at the courts without tripping off a riot in my chest. Old age, disease, death—those worries I displace each month with the slice the school takes from my check. But I could retire. I’ve put my time in for the state, the house is almost paid for, and I have enough socked away. The girls won’t need help. Elizabeth’s married to a lawyer handling Apple’s suit against Microsoft, so she’ll be set up well into the next millennium. And Mary wouldn’t ask if she did. As for Margaret, she wouldn’t know how to quit. It would be against the Plan. She’ll clock in until she’s 65, so she won’t need anything, either. And if I can do it, why not?

Why should anyone be upset here? Because it also occurs to me I have been lucky. I had the right age for the wars, too young for Europe and Korea, too old for the rest. I got into the state system when California was still flush, when the pay showed some respect for the profession. And we moved to Saratoga when a teacher could buy a house, when you didn’t have to be a millionaire to buy a house in the hills. Because isn’t that supposed to be part of what we work for and look forward to, a place of quiet, the means to inhabit it—a house with a garden out back, a garden, our peek at paradise, our reward for not getting divorced too often, for not coveting our neighbor’s wife, for raising two kids who did not turn into junkies or welfare mothers, for kneeling twenty-five plus years in the temple of American higher education?

I look at our garden—

Only lucky.

There is a plan to a garden, practical and esthetic. She studies the habits of insects and fungi—Margaret has an aversion to spraying with chemicals—and our odd lot has to be factored in. The terrain is uneven; ground water comes up in unexpected places. Dig down one spot, and the hole fills; a few feet away there is nothing but hard clay. And plants have to be arranged in a pattern by their size, their foliage, and the color of their blooms, and the times of their blooms scheduled, annuals interspersed with perennials—

None of which matters now. Yet if the loss of the garden has disturbed her, she hasn’t shown it. And if these plants have meant anything to her over the years or moved her in any way, I have not seen it, or know what it is. There is no plan to her Plan. It is just something she does.

War news, then. But my newscaster has beat a retreat to make way for other news. The other news: a bloodless military coup in Thailand, a military crackdown in Albania, bloody; division in Yugoslavia, some hope for some reform. In the USSR some guy named Yeltsin wanting Gorbachev to step down. Software piracy by a firm in Chicago, a hefty fine slapped on Du Pont for toxic waste, the Administration’s proposal to deregulate banks. Governor Pete’s railing against the state teacher’s union, the snow pack down in the Sierra, more drought predicted. The usual murders and rapes.

I spin the dial.

On the other stations: self-help on investments, cars, computers, home improvement, and divorce. No sports yet, but plenty of music, some champagne classical, the rest pop stuff I no longer recognize, running a spectrum from raw to schmultzy sentimental.

Not retire. One might as well work until he is feeble-minded enough to believe his life has been worthwhile.

I thumb through the poems, looking at my notes—when did I write all these? My scratches crowd the margins, different hands in varying slants with varying cramped postures, ciphers on the yellowed pages of my various selves, fading voices from the past. The temptation is to trace a progression, like failing eyesight, of a falling from legibility, but I don’t know when I wrote which or if they follow that order.

I look at my notes on Little Gidding. 1942 minus 1888—actually, Eliot wasn’t that old when he finished the Quartets. He went on another twenty years, but I don’t think he wrote much else.

Somewhere in the pines, the raucous call of a Steller’s jay.

He was a year younger than I.

She’s right. I couldn’t stand it, retirement. But I have stood the self I have been stuck with long enough, and could stand him a few years more.

Bitch.

.

.

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered.

It’s a prescription for a hangover. It’s not working. The poem is not becoming any clearer and the English teacher’s headache is getting worse.

Still stuck in Burnt Norton. He picks up themes and reconsiders them in other contexts, other images, other rhythms, different voices. I guess he’s talking back and forth to himself, like instruments in chamber music, hence Quartets. Hence the teacher’s head. But here he must be getting down to brass tacks so I’ll give it my best shot. Not this, not that—he’s trying to talk about Something Else again. There must be a Point to the still point, and he’s trying to figure out how we can get it. Dancing is a figure of participation, our movement in the world. But since Something Else is beyond the transience of life, the metaphors of place and motion are not enough. We can only make our best guess at what it might be, what our relationship might be to it. But if we’re caught up in the movement of the dance, we lose sight of what we’re doing, so we have to step back and let go.

First:

The release from action and suffering, release from the inner

And the outer compulsion, yet surrounded

By a grace of sense, a white light still and moving

Then:

both a new world

And the old made explicit, understood

But we have to dance first to find that out. Yet since beyond us, we’ll never get it right, our eyes deceive us, our best guess will fail, so we detach ourselves from our selves, purge our desires, our wish, don’t look, don’t hope,

Descend lower, descend only

Into the world of perpetual solitude,

World not world, but that which is not world,

Internal darkness, deprivation

No ecstasy—maybe then the light will come. We attach ourselves to the world and do the best we can, or negate our attachment to it and put on hair shirts.

The way up is the way down.

It’s the way the poem works back and forth, up and down, movement and countermovement, assertion and denial, hope and despair. One is the way of subtle adjustment, the other of prostration.

I’ll never make the first and am not ready for the other yet.

The way up is the way down.

Both somehow get you there.

Both will drive you crazy—

What’s with Margaret? The English teacher is lonely. Today, however, he may have to fend for himself.

Back to the war, then. Still more talk of negotiations from the box. Aziz, the Iraqi Foreign Minister, has left Moscow; Gorbachev’s been on the horn with Bush. Meanwhile, the Security Council is meeting behind closed doors. Everyone is just talking. My newscaster hides his shame.

Saddam upset us all last week with his bid for a truce. He can’t be serious, though, yet has to pretend that he is so he can buy more time to save his skin and/or wear us down. Then the Soviets got into the act, and they’ve been shuffling plans back and forth with Iraq all week. They can’t be serious, either, but have to try to look more so than we if they’re going to get anything in the Middle East when the show is finally over. And Bush has to pretend to be interested so he won’t offend our Arab allies or embarrass the struggling Gorbachev too much, but he won’t give in—he can’t and keep his face. Yet if he isn’t careful, he will lose his gorgeous war and have to fight, or worse, settle for some kind of peace.

But no one’s serious. More bombs today. We’ll bomb again tomorrow. And there is always this to lift our spirits: we’ll never run out of bombs.

Or words.

Back to the poem.

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence.

Words, words, words. Eliot talks about them, too, words. He talks about the difficulties of making sense of one’s life, of getting it down in words. About whether or not what one writes is worth the effort, whether there is anything that can be said that hasn’t be said before, or if anything can be said at all. Speech/reach, a nasty rhyme—he has his doubts. As if what a poet says makes a difference.

Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness

The pattern, the stillness, and music again—these are only words about words.

When in doubt, transcend.

It’s what I did in grad school. I wrote some junk about the influence of nineteenth century Transcendentalism on the American novel in the twentieth. There isn’t any, of course, which was kind of my point: those scabrous novels were determined by what wasn’t there. We all need something to pee on. When I got the job at State, I cleaned up the dissertation, sent it out, and someone published a few copies, which was enough to get me tenure. For all I know it’s still buried in the basements of a couple of university libraries along with the rest.

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish

I took over freshman comp because no one else would do it. No regrets on leaving lit, however. I was tired of having my students make me feel I was pulling one over on them. Also I was beginning to wonder if I wasn’t. Traipse through this century and see what you get. You learn the writers are made of the same stuff as the rest of us. We’re crude oil, they’re high octane—the only difference is that they have been refined.

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.

Actually, I did have a plan, a reason for doing comp. My idea was to let students figure out the world for themselves. If I could get them to understand the order of words, just look at what they were saying, they might come up with something better, or at least something different.

Who am I kidding. I was unsure of myself in school and lacked ambition. Also the ex wanted to stay in the area.

Shrieking voices

Scolding, mocking, or merely chattering,

Always assail them.

All these damn papers—I know what I will find. The topics, the players have changed over the years, but I always get the same responses. From some, righteous approval, anger against unseen enemies; in a few, holy indignation, the whimpers of martyrdom. Either way, the furious desire for self-justification. But for the most part, resentment against any assault on their place in the middle of the curve, and grunts, groans, and stammering, a frenetic dash to get to the last of a thousand words. Yet why should they bother? They know school is just a way to weed them out for the corporations. If they ever get a job, business will tell them what to think later and pay them for it.

I got the awards that come if you stick around long enough.

A few students have come back to say hello.

I could have gone higher in this racket. I also could have gone lower. But I couldn’t have done anything better or worse—

I haven’t done a damn thing.

You spend a lifetime trying to gain the quiet that comes from completion, the coming together of parts—

All you get is the quiet.

Maybe it is time to get out.

The Word in the desert

Is most attacked by voices of temptation,

The crying shadow in the funeral dance,

The loud lament of the disconsolate chimera.

Margaret really looked pissed off.

Ridiculous the waste sad time

Stretching before and after.

Burnt Norton, last lines.

The English teacher is getting depressed.

.

.

An hour past the deadline, still in the garden, the garden is still dead. You get used to it, though, and sit here long enough it takes on its own esthetic. All the subtle shades of umber, the intricate pattern of vines and leaves—it looks like a cubist painting, or wild embellishments, rococo. And there’s something about the smell of dirt and deadness that stuffs the sinuses but clears your head. But this will pass too. You can’t even count on the permanence of decay.

The sky is still blue, but less soft, and the sun is almost overhead, but hotter, less kind. The English teacher who sits by a garden that sits on a hill still has not found resolve or reason to get up. He is still hungover, but the focused pain of his headache has become a sloppy blur. Worse, the coffee pot is empty.

Margaret’s in the kitchen, cleaning up, banging pans. Whatever is bugging her, there are repairs to be made. But they can wait. For now, I wish she’d keep it down.

And I wish they’d get this damn war over. It’s getting on my nerves. One moment my newscaster tells me preparations are being made for the invasion, that Saddam’s time is running out; the next he says the White House is reviewing Gorbachev’s plan. Israel, he claims, is in a state of panic after the Scud missile and fears another attack. Our troops, massed on the border, are restless, and our generals worry that the moment will be lost. I suspect, however, my newscaster is making all that up. He is the one who is panicky and restless. He has lost his art, is fumbling badly, and has run out of things to say.

Everyone’s on edge and sloppy today. More bombs will calm us down.

Or more Eliot:

In my beginning is my end.

East Coker—I have straggled into the next Quartet. There is a time, he tells me, for houses to rise, houses to fall, for houses to live and die, a time for building and generation, a time for the wind

to shake the tattered arras woven with a silent motto.

My notes:

1939-40

East Coker: West Country village. TSE’s ancestors departed from, 17th. cent.

Departed for the New World. I don’t know if they made it to California, though. He returns to his ancestral home, then harks back to the past. I suppose you have to start somewhere, and home as good as any. It’s where you end up that is the problem.

In that open field

If you do not come too close, if you do not come too close,

On a summer midnight, you can hear the music

Of the weak pipe and the little drum

And see them dancing around the bonfire

The association of man and woman

He imagines some ancient rite. Too close, too close—the repetition is haunting, but the rest is rather quaint. Dancing again—we are supposed to be reminded of the still point, of the pattern. Of whatever. Now he adds marriage to the stew.

In daunsinge, signifying matrimonie—

A dignified and commodiois sacrament.

Two and two, necessarye coniunction,

Holding eche other by the hand or the arm

Whiche betokeneth concorde.

Eliot’s first, as I recall, was less than stable. But we won’t hold that against him. I think he was weird about sex, too. So hard to be normal—we won’t hold that against him, either. My note in the margin:

E Coker: home of Sir Thomas Elyot—related? Wrote The Boke named the Governour, 1531: moral treatise on education of rulers; dancing/soul

He has slipped in a direct quotation from Elyot’s book, he does stuff like that. It’s what endeared him to us in grad school. What’s his point? Good dancing makes good marriages, good marriages make good kings? We should all dance to the music of the spheres? Eliot the royalist rearing his purple head. But someone as subtle as T.S. couldn’t be so obvious.

Then again, maybe that is where subtlety leads.

Round and round the fire

Leaping through the flames, or joined in circles,

Rustically solemn or in rustic laughter

Lifting heavy feet in clumsy shoes,

Earth feet, loam feet, lifted in country mirth

Mirth of those long since under earth

Nourishing the corn. Keeping time

He is getting sentimental—is Glen Miller next? Lots of corn has been nourished since Elyot’s time, more is on the way for Eliot, because as he writes this Germany has run through Poland and France, and England is waiting its turn. I suppose he is trying to find an anchor in a time of crisis and turns to the past. And his point here is not final, he has more to say—

But why look back at all? What can we learn from the past except how to perfect the mistakes we have repeated?

Tedious crap!

Rite, ritual, and romance—they are ways to make us blind. Good tyrants make good kings. Try to get them to dance to another tune. And marriage gives us the illusion we are together, then sets us up to be led by the nose. Marry us off, get the flocks together, beat the tribal drum. Put clogs on our feet, dress us up like rubes, and have a hoedown. Dance, dance, dance. Dance our blues away. Then stick a gun in our hands. Hitler and Mussolini knew that very well. As does Saddam. And Bush. And everyone else.

And good craftsmen make good fascists. I’ve listened to recordings of the poet reading his work, heard his careful pronunciation of all those difficult foreign words in his tremulous, singsongy voice—it is the music of a fastidious, failing fop who licks the first boot that comes along.

Dance, dance, dance.

Bomb, bomb, bomb.

Here there may be correspondence.

Because how did this thing happen? OK, Saddam’s not a very nice guy, but Jesus, what a dancer! Because didn’t Saudi Arabia and Kuwait foot the bill for Saddam’s holy war against Iran a decade ago because of their uneasiness with their Persian brothers in the faith? And while the Soviet Union provided arms, didn’t Europe’s weapons merchants cash in as well? And, in spite of the Soviets, didn’t we kick in a few bucks and support him, too, because of our holy hatred of Khomeini who deposed that angel of democracy, the Shah our coup stuck in? And then, in our soft-shoe shuffle of linkage, didn’t we also sell arms to Iran so we could maintain balance against all those wayward Muslims, so we could fund our own sacred war against the Sandinistas next door? Eight years of stepping to the music of mass slaughter—the world trained Saddam how to boogie very well.

And now Gorbachev has his generals on his back, mad about his losing Soviet presence in the Gulf, so he does his two-faced two-step, he tries to strike a deal. And now Saddam wants to get Israel in the dance. A few well placed bombs, if he can get them there, would do the trick. But the Israelis have too much to lose if they hit the floor because that would break the coalition and could turn the Arabs against them, against us. We have to show Israel we won’t skip a beat—our Holocaust guilt, the Jewish lobby, our love for non-Arabs who will bear the brunt of Mid-East flack—yet still tap-dance to the tune of peace because our bombing of Iraqi civilians has upset the Arab world. Europe has been upset with us, too, and only grudgingly follows our lead, yet they can afford to waffle—they aren’t so much involved. And what did they expect when they armed Saddam, or when they passed the baton to us? England, however, Eliot’s precious England, has been behind us all the way, England who, after the Nazi waltz, left the political mess in the Gulf when they pulled their Empire out. We could trace this tune back to the Crusades.

But the blood from the bombing is nothing compared to what will be shed if we attack. And if more Arab blood is spilled, the poor Arabs will see their oil rich Sheiks shake and shimmy in their dependence on us, their partners in this dance. And spilling U.S. blood would not play well with us, or the mixing of our blood with Arab. So we dance and we bomb and we bomb and we dance. This is the way the world works, this is the new world order. This is the tune of linkage, the music of the spheres, this is the dance along our arteries, the circulation of oil through our lymph.

And we probably would have let Saddam take a little of Kuwait, maybe a lot, because that would not have broken up the dance. Saddam’s only crime is that he got too greedy. Or not even that. He was just unlucky: he was left standing without a chair when the music stopped—

But the thing will happen.

It will happen, and it will have to happen soon.

Because how much longer can we let all that oil burn? And not just because of the oil, or not even because of the oil, because we never kidded ourselves about that, but because of the lyrics, because of the words, because if Bush waits any longer, Gorbachev will come up with a plan whose terms match his own, because then we will all see what we don’t see now, what lies behind the words or, rather, what does not, because when words fail because they always fail, the only thing left to do is act—

I read aloud, to the garden, everyone, all together now:

O dark dark dark. They all go into the dark,

The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant,

The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters,

The generous patrons of art, the statesmen and the rulers,

Distinguished civil servants, chairmen of many committees,

Industrial lords and petty contractors, all go into the dark,

And dark the Sun and Moon, and the Almanach de Gotha

And the Stock Exchange Gazette, the Directory of Directors,

And cold the sense and lost the motive of action.

And we all go with them, into the silent funeral,

Nobody’s funeral, for there is no one to bury.

It is only the Eliot who doubts I can believe.

Margaret—

At the kitchen window—

What is she looking at?

She is looking at me.

Now she’s gone.

How much longer is she going to keep this up?

You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there

No help from my ancestors. My people were Scotch-Irish, the Lowlanders King James sent to Ireland to tame the unruly Catholics. When they got to Pennsylvania they became Americans: they cleaned the slate. Only a few words from a great-grandfather who fell at Chancellorsville, letters from Libby Prison of desperate, starved faith.

Give us the time and the resources, and we will find a way to clean the slate for good.

Not retire—

.

.

“What will you do.”

Saint Margaret—

“What will I do about what?” I didn’t hear the door. She has come straight to me and stands in a rigid pose that struggles with ease. Her long narrow face, serenely, solemnly attractive when unworried, is taut not with anger, but with her attempt to compose her indignation and turn it into something pleasant. From her breasts, a weary sigh. She is preparing to get down to business.

“What about school.”

“What about it?”

“When you retire.”

“When am I retiring?”

“When you do retire.”

“They will replace me. They’ll hire two part-timers and save a few bucks.”

“What about your students.”

“They won’t know the difference.”

“What about you.”

“What about me?”

“What will you do.”

“What am I doing now?”

The muscles in her cheeks ratchet one notch tighter. Her tone, however, does not waver. In her eyes, the avoidance that comes with a direct look.

“What will you do with yourself.”

I will not give in to this. “I will write a novel.”

And tighter.

“What will you do.”

“I will eat a novel.”

And tighter.

“What will you do.”

“I will burn a novel.”

Still tighter—it is not a pretty sight. If she would just lose her temper so we can both see what this is, then we could take it where it should go, or at least have a decent fight.

“What will you do.”

“I will dig a hole and bury myself in the garden. Maybe something will sprout this summer. Why don’t you sit down?”

“Why don’t you turn that damn radio off? This war has made you morbid.”

“Someone has to listen.”

“Someone could find a better way to spend his time.”

“Better an honest bum than a busy fool.”

“Better to do something worthwhile.”

“It is because people are trying to be worthwhile that the world is so screwed up.”

“I’m not as clever as you—”

“I’m not clever at all; I’m an idiot. And you could do a better job of hiding your contempt.”

“It is difficult to appreciate what is put to ill use. You will only get worse at this.”

“I will get better.”

“I don’t pretend to have all the answers—”

“Then what do you have?”

She stops and retreats without lowering her eyes, gathering herself inward to that wordless, weedless place where she wants to put me. Prone on the deck, side by side, two shadows, dwarfs of a married couple; one slouched, one erect, both sadly comic, not touching.

“I have a life,” she says at last.

There is no reply to that. I stare at her, her cheeks go slack, then she loads up to start again.

“I think I could take your becoming an alcoholic.”

“It takes practice.”

“Or maybe you could have an affair with one of your students.”

“I will give the matter full consideration.”

“I don’t care that you don’t care about me. I don’t care what you care about. I think I could take your scorn, I’ve taken it so long. But if you think I’m going to spend the rest of my years watching you abuse yourself, you are wrong. You’d better find someone else to do it.”

“Then I shall become an accountant. I will learn to keep the books on men’s souls.”

With that she turns and goes back into the house.

That shriek, the door—

She isn’t serious. We’ve been at it too long to start over. This one’s good for two or three days, a week, tops. We will avoid each other the rest of the day, then have dinner without speaking. One of us will stay up late until the other falls asleep. Sunday will be a little tricky. But gradually we will get back into the rhythm. Her pointed silence will yield to embarrassment over losing her cool, then she’ll start acting as if nothing happened, and we will pick up where we left off. It’s part of a dance routine we’ve worked out. It’s called not stepping on each other’s toes. We will find little things to talk about, then our jobs will take over. Neither of us will apologize, a frivolous step we dropped years ago. And I will manage to behave. It is a good diversion and I can be good at it—

I will not give in to her. I will not be turned into something pleasant.

But her first time. I’m always the one who talks about splitting up.

She isn’t serious—

Her car—

.

.

You think you know someone, but all you know are the habits, the positions you work out to keep each other at arm’s length, at that unbreachable distance that comes when you are close, and then something disrupts the rhythm, a pause in the music, a break between numbers, the noise of a war, and you wonder who she is before you, her stiff hand already sliding from your shoulder, you wonder what it was that kept you together, and then you find yourself in the middle of the dance floor, by yourself, and you wonder where you are, you hope the music starts back soon—

We dance and we dance and we follow—

And the bombs keep coming down.

In the uncertain hour before the morning

Near the ending of interminable night

At the recurrent end of the unending

After the dark dove with the flickering tongue

Had passed below the horizon of his homing

While the dead leaves still rattled on like tin

Little Gidding. 1941-2. My note on dove: Nazi bomber—the irony is too large to be ironic. Germany has finally made it to Eliot’s front door. He sees himself as a fire warden surveying the damage after an air raid in London, a nice pose for a poet. Then a schizophrenic passage where he pretends meeting someone on the streets who reminds him of himself yet also other poets, the greats, long dead and gone. He imagines them talking to him, and they give him this advice:

‘From wrong to wrong the exasperated spirit

Proceeds, unless restored by that refining fire

Where you must move in measure, like a dancer.’

Still the worry, still the doubt, but I sense elation breaking through. Terza rima without the rima—he’s hitting his stride, he must feel he’s got his hands around something at last. He is only a man, only a poet, one of us, but has decided what is true for him could be true for us all, that, in case we missed it in the first three poems, to dance we need to pray.

Little Gidding, my note: the site of an Anglican religious community cleared out and burned down by Cromwell and his faithful Puritan crew. It is where Eliot wants us to return to contemplate Nazis, where he wants us to get dive-bombed again.

The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge from sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre—

To be redeemed from fire by fire.

Because now the dove has become the Holy Spirit, a flaming angel pounding us into absolution, redeeming us from the fire of destruction with the purifying fire of faith.

What’s the difference?

Who then devised the torment? Love.

Love is the unfamiliar Name

Behind the hands that wove

The intolerable shirt of flame

Because since we can’t love ourselves or each other but only what flees from us, what is beyond us, we turn love over to Someone, Something Else. But Something Else is only the burning residue of our selves extinguished by the flame, selves collected and displaced, selves hidden from us by the act of consecration, selves blinded by the purity of our beseeching. And in the afterglow of self-immolation, our pain becomes a joy, we think we have found something. We call it meaning. And we think we can go on.

So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

And all shall be well.

Let us pray.

Either:

We take despair, our failures and throw them up into the air, then let them fall on our heads until we are beaten senseless. They fall, we fall, we hug the ground and chastise ourselves with our selves and make them bleed and sing.

Or:

There is no other course but the one we have chosen, except the course of humiliation and darkness.

Or someone does the burning for us.

Saddam Hussein. He said that a few days ago. My newscaster has just quoted him, trying to set the stage for today’s events. Now he puzzles over Saddam’s words, trying to figure out what they might mean. A ruse, he’s bluffing, he’s putting up a front to scare us—

Or Saddam could be pure and humble, too. Also Bush and all the other Roundheads. Because who’s to say they’re not believers? They’ve just found the way to turn faith inside out, to turn it not on themselves but on everyone else.

Because what’s the difference between their fire and our Anglican’s? We get turned into ashes either way.

And one kind of faith may feed the other.

Now he measures his words carefully, with reverence and with awe. Over a half million troops on either side, the newscaster tells me, and it is difficult to know how many of theirs we’ve taken out. Between us and them, just as many land mines. And miles of berm and razor wire. And kill zones all mapped out. And trenches they’ll fill with burning oil. They have been months getting ready for the attack, have buried themselves deep in sand and cement. No airplanes, but they still have big guns. And chemicals—we’d better count on all stops being pulled.

Now his voice lifts cautiously as he talks about our preparations last night. Massive carpet bombing to soften them up, and cluster bombs, steel rain. And phosphorous shells. And fuel-air explosives—the mist that turns air, lungs, and spirits into living fire. And napalm—there’s a memory, our dove in Vietnam. The argument about how many soldiers we’ve hit is largely a debate over degrees of hugeness. As for the living, only the Republican Guard is well trained, which Saddam may try to protect. The rest are poorly trained civilians pushed to serve—poor slobs like the rest of us, like us all.

Still talk of negotiations, but they’re only a formality, he says with a joy he can scarcely contain. He is happy now, my newscaster, he sounds ecstatic. He sounds not only as if the thing has begun, but as if it is already over.

But his ecstasy is premature. Those slobs can’t go back to Baghdad in defeat, nor can they expect anything from us. Either they lie down and get slaughtered or they come out and fight. They will have to become believers, too. The faith of the world has given them no other choice.

History is now and Kuwait.

Let us still pray.

It will be a long and bloody war.

It will be a long and bloody war, but we will be able to claim a word, and that word will be Victory.

It will be a long and bloody war, but we will restore our faith in ourselves and in our faith.

It will be a long and bloody war, but it won’t be long before we find the need to forget it.

Not retire. Maybe it is time to enlist.

I can’t remember the last time I saw her cry.

.

.

Eliot, objective correlative:

a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately invoked.

I went into the house to find this. It’s a theory of poetic expression.

Against the back fence cling the corpses of desiccated vines. The fine, fernlike leaves on the jacaranda have lost their color and curled even finer. The delicate patterns they once made against the sky now look like so many fish skeletons, hanging limp from the tree. The pods that carry its seeds, hard and black, have started falling, too soon, too dead. Whole limbs have dropped from the other trees. The leaves on a cape honeysuckle by the house, which she pruned to look like a tree, rained down last week, almost at once, still green, now brown. At the base of its thick stem, black cracks have appeared where water gathered, froze, and swelled. A jade tree and some other succulents, whose names I do not know, have turned into dark rubbery monsters, cripples with gnarled, drooping limbs.

And there are many more plants whose names I never learned, each different in its individual decomposition, in the writhing twists and breaks of its stems, the failing filigree and serration of its leaves, the particular clench of shriveled petals if it was a plant that flowered in winter—all of them now beyond identification. On the ground the litter of debris piling upon debris, a complexity of runners and roots and vines and fallen leaves and branches, resolving into the simplicity of dirt.

The roses—a dozen bushes—only show their thorns.

What do I feel.

.

.

On a clear day like today, if I got up and looked over our fence, I would see all the way from the foothills to the bay, the hills green with indifferent, indigenous weeds, the bay a sliver of silvery reflection. And I would see all that is between them, the valley, the roads, San Jose and the other towns where we have transplanted ourselves, miles and miles of the spread of our sprawling lives, of the grid of our motion, of the crossings of our lives together, of the improbable constructions that house our aspirations, of the breath of our uncertain, weedlike growth—

But I do not get up.

If I looked up, I would see a sky that thinks it’s blue, a hot sun short of midday that strips me of that illusion, of the illusion a sky can fill empty space—

But I do not look.

Instead I stare at a poem.

He tells me he does not know much about gods, but he thinks the river is a strong brown god.

I have skipped The Dry Salvages. How did that happen?

I skim through this one without reading it. Not much underlined, no notes. Either I understood it well enough some time past, or did not understand it at all. Or perhaps I understood it too well. Salvages—Eliot provides his own note—some rocks off the coast of New England. Rhymes, he tells me, with assuages. He can’t wash the New World off his hands.

There is no end of it, the voiceless wailing,

No end to the withering of withered flowers,

To the movement of pain that is painless and motionless,

To the drift of the sea and the drifting wreckage,

The bone’s prayer to Death its God.

He should have stopped there.

Better not to have said anything at all.

.

.

The sun is directly overhead, white hot; the blue has gone away.

A portable radio has been thrown over the fence—

A rose is a rose is a rose.

A rose was a rose was a rose.

Light is light is light.

The world is the world is the world.

A word is a word is a word.

The world is a word is a war.

The way up is the way down.

The way down is the way up.

The way down is the way down. . . .

.

.

The sun. . . .

.

.

The door—

Margaret—

She’s back—

I didn’t hear her car—

She stands again at the opening, wearing leather gloves and black rubber boots that trumpet at her calves. Dry-eyed, without expression, she pauses there a moment, gazing over the fence. In her hands, across her chest, a new pruning saw with a bright chrome handle and the straight smile from a blade of large, angry teeth.

This is how the day has gone. This is what one should expect—

But she acts as if I am not here. Instead, she goes over to one of the rosebushes and hacks away with vigorous yet steady strokes. The thorns grasp and tear her clothes. She doesn’t seem to notice. She stops, she drops the saw, then stands back and contemplates her butchering, partially complete. A hushed world gives silent approval. On her face, the look of satisfaction.

Pathetic. This gesture was meant for me—

Back to work. She stoops and yanks a small shrub by the rosebush. It breaks off at the roots. That does not satisfy her and she hurls it against the fence.

Because what she is doing to the garden is what she thinks I have done to her—

She shakes her disappointment, turns, and, crushing crisp deadness under her boots, trudges to the cape honeysuckle. Grabbing high on its trunk, she pulls back with all her weight. A few hard tugs and it snaps; she falls on her rear. But she is up before I can think about giving her a hand, and holding half a tree, she stares at it without anger or regret. It is heavy, she lets it fall. On the shoulder of her white blouse, already dark with sweat, a few spots of blood.

But what she is doing to the garden, what she thinks she’s doing to me, she’s also doing to herself. Still, I don’t get up, but sit and watch. There is nothing to think about here, nothing that can be done. I know I cannot stop her.

She steps back, and, arms folded, considers what to do next. She has decided. She walks to the house, unloops the hose from the hook, opens the faucet, and goes back to the middle of the garden. Then she adjusts the nozzle to a narrow, violent spray and turns it on the plants. Vines jump, branches shudder, the spray deflects and scatters. Dry leaves crack, snap, and fly, which she beats back down with the hose.

Not to me, not to her—

Yet still she keeps on spraying, eyes focused where the stream hits, strafing long strips, then shooting individual plants until they are drowned in mud and water. A few minutes is all it takes to turn the garden into thick soup.

I don’t know what this is—

Now just the loud but even sound of the torrent from the hose and a splashing in fresh puddles. And still she keeps on spraying, her face still serene and full of purpose. And still I don’t get up, but sit and stay. It’s the least I can do for her. But I can’t watch this anymore, so I pick up a book and read.

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is un—

The stench hits me, a fecal smell of dirt and rotten life, heavy, wet, and sick—I can’t sit still any longer. I don’t know what she’s doing, but I might as well get up and join her.

When I come back from the garage, she is stooping, lifting plants, and throwing them against the back fence. It splatters with mud when they hit. Already at its base, a small pile growing larger.

I plug in the extension cord and run it to the jacaranda. Then I connect the circular saw. Whatever this is, I will make quick work of it.

The purplish mist of the tree’s tiny blooms always embarrassed me somehow when the thing was alive. What is now left disgusts me. The pods, the fronds, the way they cling—locking the switch on the saw, I reach high and rip through slender, sapless branches. With a few flourishes I have the tree down to a stump.

I try to pull the stump up. The bastard will not budge. I kick it hard, and still it doesn’t move. I go to the garage and bring back an ax. Swinging at the base, I aim for its roots, not knowing where they are. When I’ve circled the stump, I try to lift again, but it has scarcely weakened. So I swing wildly, deep into the ground, not thinking about my feet or damage to the blade. Then I try once more to pull it out, and now it comes out easily.

I stare at the upturned stump—a black, gnarled hand with severed fingers—feeling queasy and contrite. Then I look at myself—I’m a mess, and I forgot to change my clothes. Then I look at the carnage in the dirt, then down into the pit I have just made. Lightness in my head, a vacant joy. Murder must feel something like this. Or suicide. Or both.

No passion on Margaret’s face, but squatting now, she has found momentum. She thrusts, she grabs, she tosses; plants sail and slap against the fence. The pile is huge—she’s almost half done, the fence is almost half covered, almost half the garden is down to dirt. A kind of passion, though, in the rhythm of her motion, a kind of passion in the sensuous mud that clings to her and makes her pulsing torso shine. It is the kind of passion that has moved the world today.

What next? I’m at a loss for procedure here. I decide I might as well pull the remaining roots, which don’t come up without a fight. Then I go to the cape honeysuckle and finish it off with the saw, then give its stump a hard yank. But it comes out with all the roots intact—her spraying must have loosened the ground. Then I saw the roots and branches of both trees fireplace length and stack them on the deck. When I see the neat pile sitting there, I feel the passion myself.

The roses, then. I take the ax to the nearest bush, the one she first attacked.

“Keep an inch or two off the ground,” she says, not turning, before I have a chance to swing. I am not going to argue with her again today.

I don’t trust my aim with the ax, however, so I try the circular saw. But the branches are too low and the thorns too thick to get the blade on its base, so I start at the top and attempt to work my way down. Yet as I shove the saw into the upper branches, they close around my hands and scratch, and I can’t push the blade hard enough against them to raise the metal guard. So I hold the saw with one hand and pull back the guard with the other, baring a full half circle of its whining rage.

I lunge, I feint, and still get scratched. My hands sting, my back hurts from bending; the passion turns to fury. But only after many fierce attacks and quick retreats do I finally succeed in taking the bush down to a stub. Then I lift the branches gingerly and carry them to the deck, and still get scratched. And still eleven more to go.

I charge into the next bush. When I finish, my hands are screaming. Then I realize I should have worn gloves, but no point in going back to get them now. When I finish the third, I look at Margaret, and see she’s three-fourths done. I rush through another and throw its branches on the deck instead of carrying them, trying to catch up with her, but doubting I can.

Mister Lincoln, Queen Elizabeth, Eclipse, Camelot, Cathedral, Honor, and Pink Peace—I tear through rulers, virtues, cosmic events, and mythical and religious places, and slash memories of their buds’ subtle colors and soft flesh, turning them all to caustic dust. But I tire and begin to lose the passion. Then my method decays to sloppiness, then to desperation. And anger dissipates into numbness, the pain from scratches into to a dull burn. Then I don’t feel that. Then I’m on my knees at one bush, and don’t rise to go to the next. This must be the way that a massacre goes. I don’t know, however, why it took me over fifty years to realize such behavior is normal.

I look up, and she is nearly done, the ground is almost clean.

I look up again, and she is gathering the debris and putting it in plastic bags.

I look up again, and the bags are on the deck.

I look up again, and she is smoothing the ground with a rake.

When I finish the last bush, weary and still kneeling, I look at my red hands. The pain, I think, will come back after they heal. What I feel now is what one feels when he has passed the point of feeling. Then I stand. My knees cry, my back cracks, blood rushes from my head, the sky, the earth turn black—

When my eyes regain focus, I see she has finished raking the last bush, then see the result of our separate labors. Dirt one somber color, dark but no longer slick with water, the ground clean and level, with faint, even furrows from the rake that cross the terrain in so many parallel lines and circle the stumps of a dozen roses—the yard looks grimly marvelous, like a Zen garden or something else. Then I see Margaret, leaning on the rake. Filthy, ever expressionless, she doesn’t look like anything, yet looks marvelously grim in her exhaustion. She looks sublime.

Only now do I see her plan today: she just wanted to clear out the dead accounts.

Also that there’s a chance I have made a few other mistakes.

So much can be predicted at this point. A hot shower, some place of seclusion. One of us will probably go out to dinner. Maybe I’ll drink again, but I doubt it. I really don’t enjoy it that much. Besides, Sunday I’ll need to be sober to prepare for Monday’s classes. Maybe instead I’ll give Eliot another shot—there may be a point or two I missed. And then I’ll watch the news tonight to see if anything has happened in the Gulf. But this is the miraculous part: after the news, I don’t know what will happen next.

“The roses will come back” she says, but not to me.

She tells someone they are sturdy.

— Gary Garvin

.

Gary Garvin lives in San Jose, California, where he writes and teaches English. His short stories and essays have appeared in Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel.

.

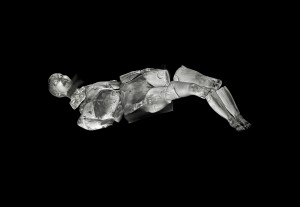

Bradd Allen Saunders. Photo by Dana Saunders.

Bradd Allen Saunders. Photo by Dana Saunders.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein