Last Judgement by Jan van Eyck

Last Judgement by Jan van Eyck

“Consider a little, if you please, unmerciful Doctor, what a theater of Providence this is: by far the greatest part of the human race burning in flames forever and ever. Oh what a spectacle on the stage, worthy of an audience of God and angels! And then to delight the ear, while this unhappy crowd fills heaven and earth with wailing and howling, you have a truly divine harmony.” — Thomas Burnet, De Statu Mortuorum Et Resurgentium Tractatus, (On the State of the Dead and the Resurrection) posthumously pub. 1720

1

George Coyne, S. J., former Director of the Vatican Observatory and currently McDevitt Chair at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, recently repeated to me in conversation a question posed to him by the late Carl Sagan, of Cornell and Cosmos fame. Sagan’s more-than-rhetorical question, as fellow astronomer and seeker, was a compelling one: “Why should you be given the gift of faith, and not me?” Coyne acknowledged that he had no full answer, though he surmised that his reception of the gift of faith had much to do with his own actions, specifically his having read Augustine and Aquinas.

So have I, but, alas, that reading gradually but permanently shook rather than bolstered my faith. Listening to Fr. Coyne’s report of his response to Sagan, I recalled being disturbed, as a student at Fordham University, by the insistence of Augustine that since humanity is stained with a primal sin, we are utterly dependent on God’s grace, a position that seemed to severely limit human freedom. As Peter Brown notes in his magisterial biography, Augustine of Hippo (1967, updated in 2000), the idea of an ancient transgression as an explanation for present misery was current in both pagan and Christian thought. And Augustine was, of course, steeped in Paul, especially the Epistle to the Romans, and haunted by Paul’s Adamic argument that “sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned” (Rom 5:12-13). This is a succinct statement of what would become known as Original Sin, a doctrine we associate in particular with Augustine, who, I couldn’t help feeling, spun it, whatever its pagan and Pauline antecedents, primarily out of his own entrails. Convinced that only divine grace could curb a libidinal drive he often felt personally powerless to control, Augustine, on the basis of his own sexual psychology, extrapolated a universal doctrine of primal sin, inherited guilt, and absolute dependence on the grace of God.

Consecration of Saint Augustine by Jaume Huguet

Consecration of Saint Augustine by Jaume Huguet

The result was a biographical-theological mélange that minimized, without utterly excluding, the role of individual free will. Even when he gestures toward free will, the pessimistic Augustine emphasizes the wrong choice, that of the lower rather than the higher. In a notably Neoplatonic passage in Book 12 of The City of God, he observes that “when the will abandons what is above itself and turns to what is lower, it becomes evil, not because that to which it turns is evil, but because the turning itself is wicked.” That wicked turning, which began in Eden, reduces the whole of fallen humanity to what Augustine calls a sinful “lump” [massa]. The allusion is to Paul’s Potter-God molding a “lump” of clay (Rom 9:20-21), but Augustine goes beyond Paul, for whom the lump has no right to question its Maker, who chooses willy-nilly to produce “vessels” reflecting his “mercy,” or “vessels of wrath made for destruction” (Rom 9:22-23). Mere clay is not low enough for Augustine, for whom postlapsarian humanity is a collective “lump” of sinful and damnable filth—massa peccata, massa perditionis, massa damnata (Enchiridion, 98-107). In his treatise “On Grace and Free Will” (426-27), Augustine writes that while “God foreknows what we are going to will in the future, it does not thereby follow that we are not willing something freely” (255). But his emphasis is always less on human than divine will, with salvation a free and foreordained gift of God, given gratis and independent of a person’s individual merit. Reading the newly discovered letters Peter Brown printed in the 2000 update of his biography, I was less than fully persuaded by his claim that they substantiate Augustine’s place as the “inventor of the modern notion of the will.”

St. Augustine by Antonello da Messina

St. Augustine by Antonello da Messina

“Those who love [God] are called according to his purpose,” and “those whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called he also justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified” (Rom 8:28-30). This passage from Romans clearly contributed to Augustine’s own version of predestination, which intensified in the later phases of his increasingly furious combat with Pelagius and his followers. When I first read Augustine’s anti-Pelagian tracts, I connected them with another obsessive and sustained assault I was studying at the same time in a Fordham history course: Edmund Burke’s protracted attempt (1788-95, the longest trial in British history) to convict the impeached Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India. In the end, though he was financially ruined, Hastings was not convicted: an acquittal, fumed Burke, who had stressed the “moral” dimension of Hastings’s alleged “corruption,” which redounded to “the perpetual infamy” of the House of Lords.

Augustine’s equally fervid confrontation was with the infamy of Pelagianism, embodied in Julian (380-455), the bishop of Eclanum, and the semi-Pelagian monk John Cassian, both of whom, in responding to Augustine, gave as good as they got. Like the British monk Pelagius and Julian, Cassian, an ardent disciple of Origin, emphasized human capability and responsibility in actively co-operating with God: a mixture of optimism and insistence on human agency that provoked the now elderly and crusty bishop of Hippo into angry responses, including his most extreme assertions of precisely what the Pelagians had accused him of: predestination. Or so I saw it; and though my Jesuit professors at Fordham suggested otherwise, I begged (mostly quietly) to differ. When, two years after I graduated, I read Gerald Bonner’s Saint Augustine of Hippo: Life and Controversies (1963, rev. 1986), I felt vindicated. Bonner admires Augustine and the best part of his book is his informed and balanced account of the Pelagian controversy (also discussed at length in Part IV of Peter Brown’s biography), which makes his conclusion, a mixture of admission and dismissal, all the more compelling: “Augustinian predestination is not the doctrine of the Church but only the opinion of a distinguished Catholic theologian” (592).

Obsessed with the monstrous transgression of Adam and Eve, transmitted as Original Sin, and by his theology of grace, did late Augustine plunge into the heretical pitfall of strict predestination? Certainly his pessimistic view of fallen human nature, darkened by the contemptu mundi perspective he had inherited from the Neoplatonists and the Stoics and by his own idiosyncratic emphasis on the role of sexual reproduction in transmitting Original Sin, led Augustine to claim that our natural proclivity is toward evil and that all our impulses to good are dependent on God’s grace. What makes his position darker still is Augustine’s post-Pauline insistence that the decision on God’s part as to who receives this grace is, as the word itself suggests, gratis—gratuitous, arbitrary.

According to Augustine (and Aquinas after him), while God wills the salvation of all, certain souls are granted special grace that in effect foreordains their redemption. But “why one is called and the other not” has to do with the “inscrutability” of God. “Why God draws this one and not that other,” Augustine admonishes, “seek not to know or to judge.” And later in the treatise I am citing, in a chapter titled “The Difficulty of the Distinctions Made in the Choice of One and the Rejection of Another,” he concludes that we have no right to question God and that “he who is condemned has no ground for finding fault” (De dono perseverantiae, chapter 16). Augustine is alluding to those “called according to” God’s “purpose” in Rom 8:29-30, and to a passage he specifically cites: Paul’s rhetorical question, “who are you, a man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, ‘Why have you made me thus?’” (Rom 9:20).

An early printed version of Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy

An early printed version of Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy

In short, Augustine restates rather than responds to the crucial question posed by Carl Sagan to Fr. Coyne: “Why have you been given the gift of faith, and not me?” Though, as with countless others over the past millennium and a half, I found help on this issue in the lucid prose and dialogue form of The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, as a sophomore in college, I was hardly equipped to unravel the paradoxical relationship between God’s foreknowledge and human free will. So “Seek not to know”: simply accept the idea that, by means of his mysterious “grace,” an all-foreseeing God—who made his decision before the oceans rolled, indeed before “time” itself— “predestined those he called” to eternal life, leaving others in their sin, but “justly” condemned as a result, paradoxically, of their own “choice.” Wherever one finally comes down on this simultaneously fascinating and repellent issue, Augustine more than flirted with the unspeakably horrible doctrine of predestination as it later culminated in Luther, an Augustinian monk after all, and, especially, Calvin, who claimed he could have written an entire book “out of Augustine alone” to justify his theology, a theology based on the adamant insistence that while “some,” the so-called Elect, are “predestined unto everlasting life,” all “others” are “preordained to everlasting death.” That is to say, hell—about which Augustine himself has much to say.

In The City of God, Augustine distinguished between the Last Judgment and a Particular Judgment (which he illustrates with the story, in Matt. 16:19-31, of poor Lazarus and Dives, the rich man who had turned the beggar from his door and now, dead and suffering in the flames of Hades, begs Lazarus for a drop of water.) There may be hope following the “first death” and the Particular Judgment, but after the “second death” and the Last Judgment, reward or punishment is irrevocable and eternal. Citing scripture, Augustine resisted those who argued, or at least hoped, that hell’s punishment, however fierce, would not be eternal. It would be both, he insisted—basing his position, as always, on the Original Sin in Eden:

Hell, also called a lake of fire and brimstone, will be material fire, and will torment the bodies of the damned, whether men or devils—the solid bodies of the one, and the aerial bodies of the others; [for] the evil spirits, even without bodies, will be so connected to the fires as to receive pain….One fire certainly shall be the lot of both…eternal punishment seems hard and unjust to human perceptions, because in the weakness of our mortal condition there is wanting that purest and highest wisdom by which it can be perceived how great a wickedness was committed by that first transgression. (The City of God, Books 10, 21)

Augustine, writing in 426, is more severe than Yahweh himself, who told the perpetrators of that “first transgression,” Adam and Eve, that they would “die” if they ate of the forbidden fruit, not that they were risking eternal torment in hell. To be as literal as the literalists, an eternity of pain cannot be the fate even of their son, the first murderer, since anyone who killed Cain would suffer punishment “seven times greater” than his own. In fact, from Genesis on, there is no clear reference in the Hebrew scriptures to a place of eternal punishment. Christian preachers often allude to, or actually cite, Old Testament passages. But while they habitually turn “Sheol” and the dark valley of “Gehenna” into figurative equivalents of “hell,” no Jewish translation of the Hebrew scriptures into English does so. The most “hellish” text—handled gingerly by Jewish scholars, but seized on with relish by Christian exegetes eager to prove the eternal punishment of the wicked—is the rhetorically magnificent but horrific climax of the Book of Isaiah. There the Lord says that he will make a “new heavens and new earth” for the faithful, who shall “go forth and look on the dead bodies of the men that have rebelled against me; for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh” (66:23-24).

That final verse, the one Hebrew text on which a doctrine of eternal torment can be based, “is so gruesome,” John Sawyer notes in The Oxford Companion to the Bible (1993), “that in Jewish custom the preceding verses about ‘the new heavens and the new earth’ are repeated after it, to end the reading on a more hopeful and at the same time more characteristically Isaianic note” (327). Countless Christian theologians and preachers went in the decidedly un-hopeful other direction, harping on, and taking sadistic relish in, Isaiah’s imagery as proof of eternal punishment. As we’ll later see, in the unforgettable Hell-sermon at the center of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce’s Fr. Arnall not only cites Isaiah’s worm and stench, but takes for granted that they are sensuous aspects of eternal anguish, climaxing in that “quenchless fire.” Yet it could be argued that even in his most “gruesome” image, Isaiah refers to rotting and noxious carcasses, “an abhorrence to all flesh,” not to the rebels’ continuing personality—nephesh, the soul or living being—which alone could be subject to eternal torment.

Augustine’s central ideas often had horrible consequences. In an early public debate “Against Fortunatus” (August, 392), he had declared, “There are two kinds of evil—sin and the penalty for sin” (Earlier Writings, ed. Burleigh [1950], 15). Since we are all allegedly stained from birth with Original Sin, what penalty is to be suffered by infants who die before being baptized? The Church, understandably, has long anguished over this issue—beginning as early as the 4th century, with the treatise on the early death of infants (De infantibus praemature abreptis libellum) by Gregory of Nyssa, an early believer in universal reconciliation. To my dismay, I soon discovered that the dilemma persisted long after Gregory’s attempt to humanely resolve it. A millennium later, the great Council of Trent (1545-65), famed for its lucid definitions, concluded, in its fifth session, that, “Infants, unless regenerated unto God through the grace of baptism, whether their parents be Christian or infidels, are born to eternal misery and perdition [perditionis aeternum].”

Council of Trent by Pasquale Cati

Council of Trent by Pasquale Cati

There have been many intellectual efforts, notably including the desperate if humane hypothesis of the now defunct Limbo (on which the theological doors closed in late 2005), to get the babies out of hell. But even the eminent thinkers subsequently gathered in the Vatican to form, in 2007, an International Theological Commission, though reading the “signs of the times,” could offer only a wistful “Hope”—to cite the final subtitle of the concluding section (“Spes Orans: Reasons for Hope”) of their lengthy and learned final document. Their inconclusive Conclusion was that, “there are strong theological and liturgical reasons to hope that infants who die without baptism may be saved and brought into eternal happiness, even if there is not an explicit teaching on this question found in Revelation.”

Such are the fruits of the toxic doctrine of Original Sin, as promulgated, above all, by Augustine, whose preeminence as a theological juggernaut eclipsed all rivals until the advent of Aquinas. For the formidable but bleak Bishop of Hippo, no one was exempt from punishment “unless delivered” by an inscrutable God’s “mercy” and by “grace,” which was “undeserved.” And those delivered will be a minority. Jesus himself distinguished between the narrow-gated road that will lead the “few” to salvation and the broad-gated road that will lead the “many” to destruction (Matt 7:13-14). An echoing Augustine, consigning the bulk of humanity to perdition, writes, “Many more are left under punishment than are delivered from it in order”—he adds, setting up damnation as a grim example even for those who made the cut through no merit of their own—“that it may be shown what was due to all” (City of God, Book 22). In short, because of Original Sin, we are all guilty, and deserving of hell. And when that stain has not been cleansed by the sanctifying grace of baptism, it follows, and Augustine unhesitatingly followed that appalling logic—even if the prospect of babies in hell is more hideous than the doctrine of predestination itself— that unbaptized infants must be damned: a singularly atrocious example of what “was due to all.”

The most gifted and persistent opponent of Augustine on infant perdition, indeed on Original Sin root and branch, was Julian of Eclanum, the most prominent second-generation follower of Pelagius. His writings have been preserved, primarily and ironically, by Augustine himself, who quoted freely from Julian’s attack on the doctrine of Original Sin in his own refutation, contra Julianum Pelagianum. In countering Augustine’s dark view of human nature and sexuality, Julian went to the other extreme, his optimism verging on perfectionism. He also set against Augustine’s emphasis on eternal punishment his own version of ultimate reconciliation: a theory of universal salvation (apocastasis) first fully worked out by Origen (c. 185-254), the most brilliant and radical student of Clement of Alexandria. Origen’s belief that through Christ’s sacrifice even Satan might be redeemed (restored by the refining fires to his original angelic state as Lucifer) led the Christian bishops gathered at the Synod of Constantinople in 543 to condemn anyone who said or thought that “there is a time limit to the torments of demons and ungodly persons,…or that they will ever be pardoned or made whole again.” The target was Origen, posthumously excommunicated at this Synod, and, for good measure, at subsequent synods in 553, 680, 787, and 869.

Nave of Church of the Gesù by Giovanni Battista Gaulli

Nave of Church of the Gesù by Giovanni Battista Gaulli

Julian was himself excommunicated by Pope Celestine in 430, the year of Augustine’s death, for earlier refusing to sign on to Pope Zosimus’s excommunication of Pelagius. But despite the contemporary and historical triumph of his rival, Julian’s rejection of Augustine’s doctrine of Original Sin and his revulsion from the idea of unbaptized infants roasting in hellfire has always seemed to me a welcome alternative to the somber broodings of the Bishop of Hippo. In Book 6 of his contra Julianum Pelagianum, responding to the final Book of Julian’s treatise, Augustine had reasserted his position that, because of collective guilt stemming from the sin of Adam, the inherited “contagion” of Original Sin, “infants who die without the grace of regeneration [the sole source of which is the sanctification of baptism] are excluded from the kingdom of God.” I continue to share Julian’s humane indignation at Augustine’s presuming to speak for God in condemning infants. By an intriguing accident, the theological and ad hominem attack I quote here survives only because it happened to be among the unfinished work on Augustine’s desk at the time of his death:

Tiny babies, you say, are not weighed down by their own sin, but are burdened with the sin of another. Tell me then, who is this person who inflicts punishment on innocent creatures? …you answer God. God, you say, God! He who commanded His love to us, who has not spared His own Son for us…He it is, you say, who judges in this way; he is the persecutor of newborn children; he it is who sends tiny babies to eternal flames….It would be right and proper to treat you as beneath argument: you have come so far from religious feeling, from civilized feeling, so far, indeed, from mere common sense, in that you think your Lord God is capable of committing a crime against justice such as is hardly conceivable even among the barbarians. (Opus imperfectum contra Julianum, I. 48ff)

As revealed by the final report of the theologians convened in Rome in 2007, the Catholic Church has still not found a definitive way to extricate itself from this grotesque spectacle. The Commission labored, and brought forth a mouse—a “hope” that the babies might be saved, but a hope lacking any “explicit” scriptural basis. What, one wonders, about Jesus, who, indignant at his disciples’ attempt to rebuke those who were “bringing children to him, that he might touch them,” insisted (in all three synoptic Gospels), “Let the children come to me, do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom of heaven” (Mark 10:14; cf. Matt 19:14, Luke 18:16). Or, moving beyond scripture, one wishes these male theologians had been moved by the account of the third-century martyr, Perpetua, who envisioned, in her own prison-cell, her younger brother (who had died as an unbaptized child) liberated from a place of heat and thirst, and now, thanks to her prayers, drinking at a pool and “playing joyously as young children do.” Or, finally, why not take into account Julian’s rebuke of Augustine for lacking “religious” or “civilized” feeling, mere “common sense” and “justice”?

But the deliberations of these 21st-century theologians were dominated and (to my mind) warped by Original Sin, much of its obsessive doctrinal burden to be tracked back to fifth-century Hippo. For all his indisputable greatness, this is part of Augustine’s ambiguous legacy. Historically and officially, the Catholic Church may have denied, downplayed, or backed away from, the more extreme of Augustine’s doctrinal obsessions; but because of his sheer intellectual power and the magnitude of his authority, he has cast a shadow over the past 1,600 years of Western Christianity, for me, a remarkably dark shadow. Augustine’s particular pessimistic vision was shaped by his own sexually-obsessed psychology, the theological controversies in which he engaged, and, of course, by his response to the history he witnessed in an age of barbarian invasions, culminating in the Fall of Rome in 410, and the siege of Hippo itself in the final years of Augustine’s life. But one wishes that readers, especially theologians, who have adopted or succumbed to the Augustinian darkness would also have remembered the following sentence: “Here also is a lamentable darkness in which the capacities within me are hidden from myself, so that when my mind questions itself about its own powers, it cannot be assured that its answers are to be believed” (Confessions, Book 10:32).

An admirable questioning of his own certitudes, but hardly enough to make up for the subsequent damage caused by Augustinian “answers” that were “believed” by far too many for far too long. While the Confessions and parts of The City of God remain indelible in my memory, the reading of Augustine certainly failed to bestow upon me—as it did upon George Coyne, to revert to his response to Carl Sagan—the “gift of faith.”

.

2

Whatever his inclination toward predestination and his insistence on the eternity of punishment (even of the little ones Jesus wanted near him), Augustine seems rather dispassionate about the actual witnessing of that punishment. He does remark that those who enter into the joy of the Lord “shall know what is going on outside in the outer darkness” and that the saints, “whose knowledge is great,” shall be “acquainted…with the sufferings of the lost” (The City of God, Books 20, 22). But he doesn’t seem to have taken sadistic pleasure in the torments of the damned. That ultimate form of Schadenfreude, and another pivotal challenge to my faith, was awaiting me in the pages of the other theologian cited by George Coyne as a pillar of his faith: Thomas Aquinas.

An image from the Winchester Psaltery (c. 1225)

An image from the Winchester Psaltery (c. 1225)

I learned a great deal from working through the Summa Theologiae, my reading of which began in 1958, the very year George Coyne himself graduated from Fordham. Indeed, for a time I re-oriented my thinking, replacing Augustine’s Christianizing of Plato (or, rather, the Neoplatonists) with Thomas’s Christianizing of Aristotle. Then, one fateful day, I came upon a passage in the Third Part of the Summa, Supplement, Question 94, First Article, titled “Whether the Blessed in Heaven Will See the Sufferings of the Damned.” Here, the good Doctor tells us that “Beati in regno coelesti videbunt poenas damnatorum, ut beatitudo illis magis complaceat” [The blessed in the kingdom of heaven will be allowed to see the sufferings of the damned in order that their bliss may be more delightful to them].

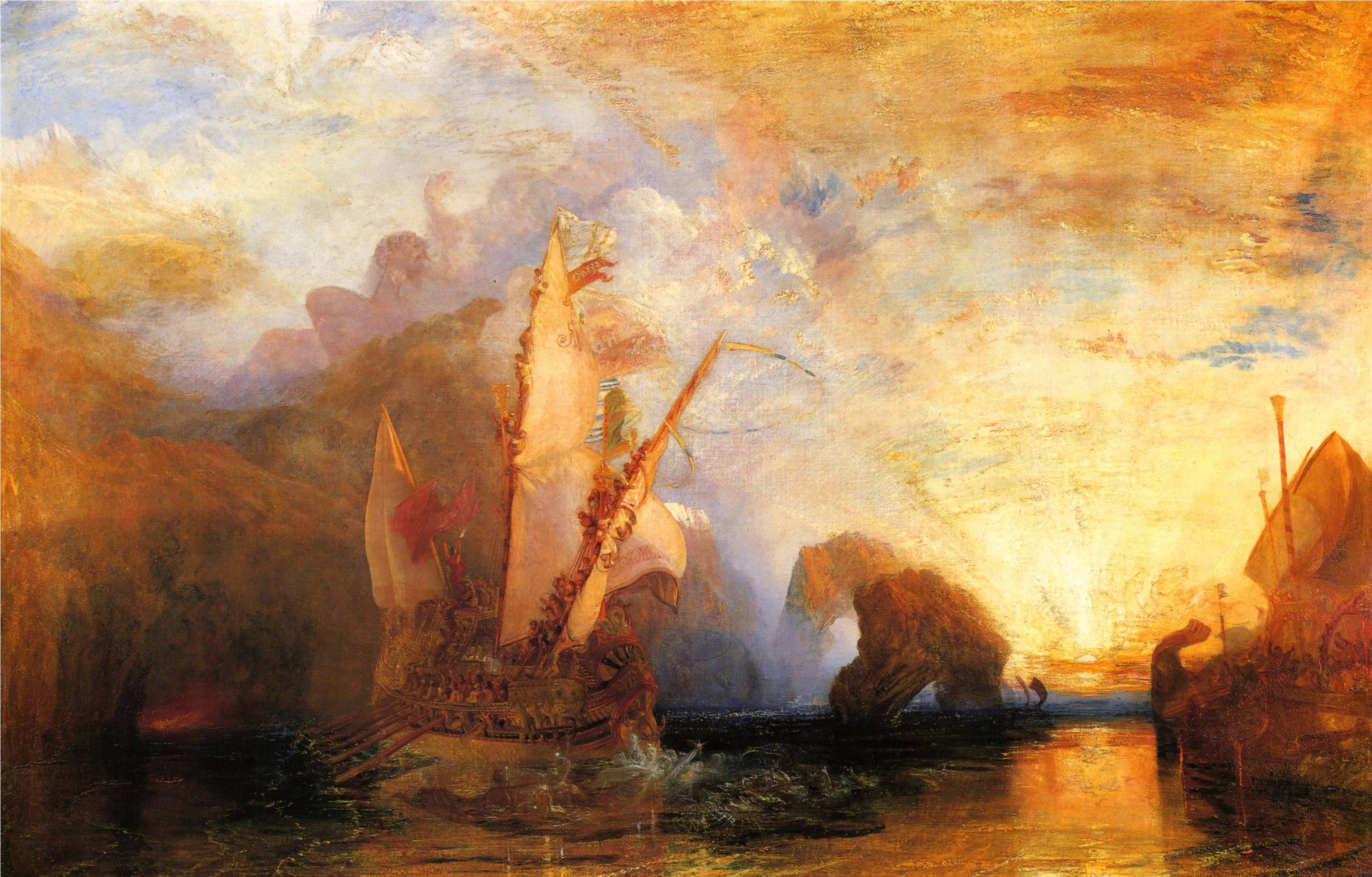

More than a half-century later, I can still recall my shock in encountering words I found morally repellent. In the years to come, I would, like all of us, encounter innumerable examples, ranging from the pettiest to the most malicious, of people taking pleasure in the temporal misfortune, even the suffering, of others. And literature provided still more illustrations. I was struck, in reading The Iliad, by those panoramic scenes of the Homeric gods looking down from Olympus, taking pleasure in the entertainment provided by the spectacular carnage of the Trojan War. I was aware, too, of a famous passage in a favorite text, De rerum natura, where Lucretius captures the emotion of Schadenfreude in an extended image: Suave, mari magno turbanti aequora ventus, e terra magnum alterius spectare laborem [It is pleasant to watch from the land the great struggle of someone else in a sea rendered great by turbulent winds]. At the same time I was reading Augustine and Aquinas, I was also deep into the Romantic poets. And so I was familiar with Lord Byron’s moving portrait of the Gothic gladiator, torn from his native land, his children, and his wife, and now about to die in the Coliseum, “Butchered to make a Roman Holiday!” (Though there was a scene outside the Coliseum in the 1953 Audrey Hepburn-Gregory Peck film, Roman Holiday, it seems unlikely that whoever titled this delightful and poignant movie had the full Byronic context of the phrase in mind.)

In light of the very different, but Coliseum-related, passage I will soon be quoting from Tertullian, it is worth noting that this butchery to please the bloodthirsty Roman spectators is not the only Schadenfreude-moment in this famous passage from Canto IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. The spectacle of the dying German gladiator, a sacrifice that pleased the sadistic Roman crowd safe in their seats, aroused the compassion, and stirred the anger, of the anti-imperialist poet: “Shall he expire, / And unavenged? Arise, ye Goths, and glut your ire!” And the passage ends on a final note of commendable Byronic Schadenfreude: a glimpse of “Rome and her Ruin past Redemption’s skill”—a sort of proleptic vision of vengeance Byron empathetically shares with his coerced and slain gladiator.

But in 1958, for all my delvings into theology, philosophy, and literature as a member of the advanced “A” Class at Fordham, I was still an inexperienced naif from the Bronx and a practicing Catholic. To encounter this passage about the bliss of the blessed being enhanced by delighting in the torments of the damned, coming from, of all people, Catholicism’s central philosopher-theologian, stunned me—especially since elsewhere in the Summa (Second Part, Question 74), Aquinas identifies delectatio morosa [morose delectation] as a sin. In fact, I was still disturbed enough a year later to finally seek out a particularly eminent Jesuit on campus, who referred me to literature on what has been called “the Abominable Fancy.”

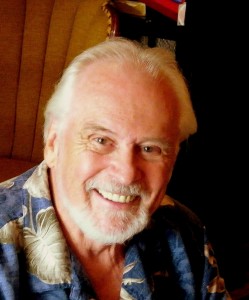

Frederick Farrar

Frederick Farrar

The term, coined by the 19th-century cleric and writer, Frederick Farrar, refers to what I learned was a long-standing Christian idea that witnessing the sufferings of the doomed intensified the bliss of the saved. Farrar himself was a believer in universal reconciliation, a position he defended at length in Eternal Hope (1879) and Mercy and Judgment (1881). In his 1963 book The Decline of Hell, D. P. Walker remarks that the idea of eternal punishment in hell (a tradition “almost unchallenged” until the 17th century) was often accompanied by the idea that “part of the happiness of the blessed consists in contemplating the torments of the damned.” He offered a persuasive double-explanation: “The sight gives them joy because it is a manifestation of God’s justice and hatred of sin, but chiefly because it provides a contrast which heightens their awareness of their own bliss.” Nevertheless, echoing Farrar, he describes it as a particularly “abominable aspect of the traditional doctrine of hell” (29).

Advocates of what Farrar and Walker condemn as an abomination cite scriptural roots, some tenuous in terms of eternal vengeance. In Psalms, for example, “the righteous shall rejoice when he sees the vengeance” (58:10) and, in 68:2-3, when the “wicked perish before God,” the righteous shall “be joyful; let them exult before God; let them be jubilant with joy.” In a favorite phrase of devotees of the abominable fancy, the righteous shall “go forth” to enjoy the suffering of the damned, an allusion to the famous finale (Isaiah 66:24), in which the faithful “go forth and look” on the rotting corpses of the rebellious; as earlier noted, the reference may be restricted to mutable bodies rather than eternal souls. But in the more explicit and far more vengeful New Testament Book of Revelation, we are informed not only that, thanks to an avenging God, the saints and prophets” shall “rejoice” over the fallen city of Rome (18:20), but that the vengeance announced by the Third Angel will be eternal and witnessed by the whole of the heavenly host, including Jesus: a gazing-down scene popular in ancient and medieval iconography. Whoever “worships the beast,” thunders the Apocalyptist, “shall drink the wine of God’s wrath,” and “shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever” (14:9-11).

This is presumably the passage to which Thomas Burnet was alluding in ironically describing the “divine harmony” produced by the burning of most of humankind in “the presence of an audience of God and angels.” But another text Burnet may have had in mind in satirizing the delight of that “audience” enjoying the agonies of the damned as an infernal “spectacle on the stage,” is the very book to which my Jesuit mentor directed me without further comment: Tertullian’s De Spectaculis, “On the Spectacles,” perhaps the most sustained and sensational illustration of the Abominable Fancy. I repaired to the old Duane Library and found the text, newly translated by Rudolph Arbesmann, and included in Tertullian: Disciplinary, Moral, and Ascetical Works (Fordham UP, 1959). Pagan public spectacles, such as those in the Coliseum, are despicable. Thus far, Tertullian and the Byron who elegized the dying gladiator are in agreement. But their versions of Schadenfreude could hardly be more antithetical.

Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips

Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips

Rebelling against but haunted by Calvinist indoctrination and harangued by a pious mother and scripture-spouting nurses, Byron was simultaneously shadowed by the fear that he was predestined to damnation and appalled, on humane grounds, by the very concept of eternal punishment. In serious works, like his great closet drama Cain, he identified with the title character and even with rebel Lucifer; and in his jocoserious moments, especially in his two ottava rima comical masterpieces, Don Juan and The Vision of Judgment, Byron mocked aspects of a religion whose catechism he knew more intimately than most believers, praising Jesus but targeting Christian cant and cruelty. In Don Juan, he dealt with the pitiless but pious burning of heretics in a single wittily-rhymed couplet: “Christians have burned each other, quite persuaded/ That all the Apostles would have done as they did” (I.83). And in stanza 14 of The Vision of Judgment, he displays a universalist tolerance and compassion alien to Tertullian’s relish in the agony of the damned: “I know,” says Byron at his ironic best, “this is unpopular; I know/ ‘Tis blasphemous; I know one may be damn’d/ For hoping no one else may e’er be so….”

Tertullian

Tertullian

Here, at last, is Tertullian on Spectacles. The greatest, and by far the most entertaining, spectacle of all, he gloats in Chapter 30, will be the Final Judgment, when the mighty of the world shall be consumed in flame. (In the extraordinary passage that follows I do not adhere to any single translation):

You are fond of spectacles? Expect the greatest of all spectacles, the last and eternal judgment of the universe. How shall I admire, how laugh, how rejoice, how exult, when I behold so many proud monarchs and fancied gods, groaning in the lowest abyss of darkness; so many magistrates, who persecuted the name of the Lord, liquefying in fiercer fires than they ever kindled against the Christians; so many sage philosophers blushing in red-hot flames with their deluded pupils; so many celebrated poets trembling not before the judgment-seat of Rhadamanthus or Minos, but of Christ—a surprise! So many tragedians, more tuneful in the expression of their own sufferings, should be worth hearing! Dancers and comedians skipping in the fire will be worth praise! The famous charioteer will toast on his fiery wheel; the athletes will cartwheel not in the gymnasium but in flames….

The scenes in which he exults, taking “greater delight…than in a circus,” are in the future. “Yet even now,” Tertullian concludes, “we in a measure have them by faith in the picturings of imagination”—just such a topsy-turvy “picturing” as he has here vividly presented. In this reversal, the pagan gods are supplanted by Christ (as in Milton’s “Nativity Ode”), pagan thought and art by the new religion, present suffering by future bliss. Oppressed by prideful pagan masters who tortured and martyred them in public spectacles, Christians will have the last vengeful laugh, looking down, as it were, from the good seats in the Heavenly Coliseum, at the “greatest of all spectacles,” the fiery Hell of the Last Judgment.

Though Tertullian’s fervid and vindictive rhetoric, a masterpiece of Schadenfreude, was reduced by Arbesmann (in a footnote) to “a colorful description of the millennium,” it had been, I soon discovered, singled out by Edward Gibbon for special censure. In his great history of the Roman Empire, Gibbon notes that early Christian hatred of “idolatrous” pagan spectacles and games embraced all pagan art and scholarship—an eternal condemnation, at the very least of those who persisted in their obstinacy after the redemptive sacrifice of Christ on the cross. “These rigid sentiments,” writes Gibbon, “which had been unknown to the ancient world, appear to have infused a spirit of bitterness into a system of love and harmony…[T]he Christians who, in this world, found themselves oppressed by the power of the Pagans, were sometimes seduced by resentment and spiritual pride to delight in the prospect of their future triumph.” After citing at length the “stern Tertullian” of chapter 30 of De Spectaculis, Gibbon adds: “But the humanity of the reader will permit me to draw a veil over the rest of this infernal description, which the zealous African [Tertullian is believed to have been born or at least raised in Carthage, in Roman North Africa] pursues in a long variety of affected and unfeeling witticisms.” (Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 15)

As intended by the Jesuit who had directed me to it, the passage of Tertullian placed Aquinas’s comment in historical and religious context, that of imperial Rome in the 3rd century AD (De Spectaculis was probably written in the second decade of that century, after Tertullian had allied himself with the prophetic Montanist sect). But that context did not make the statement of Aquinas, a millennium later, any less repellent; and Gibbon’s humane rejection of the “resentment and spiritual pride” into which Tertullian had clearly been “seduced” tallied with my own aversion from the echoing passage in Aquinas. Tertullian’s relishing of this one “spectacle” may also be echoed in another passage likely to have influenced Aquinas. The pre-Thomistic scholastic theologian Peter Lombard, in his Sentences (Libri quatuor sententiarum), written in the mid-twelfth century, speaks of the “elect” sallying forth to witness “the torments of the impious, seeing which they will not be grieved,” but rather “will be satiated with joy at the sight of the unutterable calamity of the impious” (Sentences, IV. 50).

But the more I looked into the abyss, the more I realized the extent to which the retributive hell envisioned in the Sentences and in the Summa had been preceded not only by Tertullian, but, minus an emphasis on the gloating bliss of the saved, by Paul and, with wrath rather than sadistic resentment, by Jesus himself. On eternal punishment, Paul goes into less detail than does Jesus and the author of the Book of Revelation. In the remarkably intense opening chapter of his second letter to the Thessalonians, however, Paul foreshadows the apocalyptic fury of Revelation, “when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven with his mighty angels in flaming fire inflicting vengeance” on those “who do not know God” or who “do not obey” Christ’s gospel: “They shall suffer the punishment of eternal destruction and exclusion from the presence of the Lord” (2 Thess 1:8-9).

Early in Romans, his longest and most influential letter and the one in which he has most to say about divine wrath, Paul observes that while “God’s kindness is meant to lead you to repentance,” those with hard and impenitent hearts are “storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath,” when “there will be “tribulation and distress for every human being who does evil” (2:6-10). As we have seen, the Potter-God analogy (Rom 9:21-23) imprinted itself indelibly on the rather fevered imagination of Augustine, who turned Paul’s “lump of clay” into a sinful, filthy, and doomed “lump”: massa peccata, massa perditionis, massa damnata. Even though he makes it clear that the clay vessels are preordained for either glory or destruction, Paul strikes a better balance than the Bishop of Hippo:

Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for beauty and anther for menial use? What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience the vessels of wrath made for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for the vessels of his mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory…?” (9:20-23)

Paul advises us, still later in Romans (12:17), “Do not repay evil for evil.” But there is a catch; we are to forego personal vengeance in order to “leave room for God’s wrath.” In this way, by refusing to “take revenge” against your enemy, “you will heap burning coals on his head” (12:18-21). Moderate commentators have sought to make the final and most graphic image more palatable, suggesting that it refers to a form of ceremonial repentance or a shaming of one’s enemies. Perhaps. But when, in Paul’s likely source (Psalms 25:21-22), David cries out, “May burning coals fall upon them,” he is not talking about merely shaming his enemies. He is invoking what Paul (in the very epistle in which he has most to say about the subject) has just referred to as “God’s wrath.”

Divine wrath was certainly emphasized by Jesus, who—despite his embodiment of the Love thought to be the very antithesis of the God of Wrath—spoke more, and far more graphically, about Hell than about Heaven. In an unforgettable passage (John 10:7-10), Jesus presents himself as the “door” to salvation, as the “good shepherd” who “lays down his life for the sheep,” as he who “came that they may have life, and have it abundantly.” In the light of such moving and redemptive imagery, one wants to repress the darker side of Jesus’ ministry. My heart and head are with nuanced theologians, yet it seems to me that Jesus is speaking (or being made to speak by the Gospel-authors) literally rather than (as many would prefer) figuratively in those passages in which he opens the mouth of hell.

For the “door” swings both ways. In the passage I earlier suggested was echoed by Augustine in observing that “many more” are punished than are “delivered,” Jesus said: “Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is easy that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few” (Matt 7:13-14). The road most traveled by (and Jesus does suggest that most of humanity is on the road to perdition) leads to a hell that is a place of both “darkness” and flame, a “fiery furnace” where (in a phrase attributed repeatedly to Jesus, mostly in Matthew, to describe the torments of the damned) there will be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matt 8:12, 22:17, 25:30; cf. Luke13:27-28). And when Jesus says, “Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” (Matt 25:41), the departure implies more than separation from God and is obviously permanent. The damned are “cast into eternal fire” (Matt 8:18) its flames “unquenchable” (Matt 3:12, Luke 3:17, Mark 9:43). Thus, the “many” depart to a place of agony both intense and “everlasting”—the Greek word for which, aionios, occurs 71 times in the New Testament.

.

3

That the adjective “everlasting” is applied in the New Testament to Heaven as well as Hell points to the Love/Wrath symmetry that ostensibly reconciles the great paradox: that eternal punishment is not inconsistent with the character of God, who is at once loving and benevolent, but also righteous and a God of justice, who metes out punishment as well as reward. The radiance of Jesus shines through the Gospels, despite such passages. But whether or not the hellfire passages accurately depict what Jesus actually said, they are there, and cannot simply be selectively dismissed by those who want a gentler Jesus—a Savior, but not a Sentencer. A major 19th- century theologian tried to do just that. The moderate and much-admired Anglican F. D. Maurice was dismissed from his position as Professor of Theology and Modern History at Kings College, London, when his Theological Essays of 1853 revealed his growing conviction that the notion of eternal punishment was erroneous, and based on a misunderstanding of biblical passages. Others went farther.

F.D. Maurice

F.D. Maurice

In accord with their optimistic doctrine of apokatastasis, the idea of eternal punishment was rejected by prominent theologians, from Origen through Gregory of Nyssa, Julian, Scotus Erigena, and George MacDonald, whose 1879 rejection of the idea of eternal punishment cost him his post, as it had Maurice—in MacDonald’s case, his Church of Scotland pulpit. Such universalists, right up to the present, believe that divine Love will conquer all. In the words of Rowan Williams, the controversial former Archbishop of Canterbury, “if salvation is for any, it is for all” (The Truce of God [2005], 30). Yet the idea of universal redemption also reminds me rather too much of the Dodo Bird’s response to Alice’s query about how—since the runners in the race they are watching start when and where they want—a winner can be determined: “Everybody has won,” says the Dodo, unconsciously launching a thousand theses on moral equivalence, “and all must have prizes” (Alice in Wonderland, Chapter 3).

Alice and Dodo by John Tenniel

Alice and Dodo by John Tenniel

Others, seldom with the resentment-fueled malice of Tertullian, want a judgmental Jesus, since it seems only just that the wicked be punished, if not in this life, then in the next. For those more repelled than awed by the idea of “sinners in the hands of an angry God,” the punishment is justified on the basis of the free will minimized by Augustine. Human beings are free to accept or reject Christ’s offer of salvation. C. S. Lewis is emphatic about this choice. But while he bases his argument on freedom to choose, and wishes hell away, its horrors are presented with all of Lewis’s considerable imaginative power. He also grimly notes, in The Problem of Pain (1940), that our final choice is irrevocable and that “the gates of hell are locked from the inside” (127). Free will is also stressed by prominent Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga, in God and Other Minds (1990), and elsewhere. Free choice was starkly presented in 2005 by Robert Jeffress, in Hell? Yes!—a cleverly glib title synopsizing his Schadenfreude-dripping certitude that “every occupant of hell will be there by his own choice” (85).

The smug, stony coldness of that verdict is intensified by the fact that the hell of the secularist-baiting Jeffress (as well as of Lewis and Plantinga) is “everlasting.” Even if punishment of sin is thought justifiable, surely eternal damnation, Augustine notwithstanding, is disproportionate given the brevity of human life; and grotesque in the case of those for whom history and geography ruled out knowing let alone choosing Christ. I am chilled by the thought that the gates of hell are “locked from the inside” and that every inmate “will be there by his own choice.” Nevertheless, as a professor opposed to grade inflation, I am with Alice rather than the Dodo. I also confess to being oddly stirred by the frisson of a remark the poet and Catholic convert Lionel Johnson, “his tongue loosened” by drink, once made in casual conversation with his friend Yeats: “I wish those who deny eternity of punishment could realize their own unspeakable vulgarity.” My response is precisely that of Yeats, who adds, “I remember laughing when he said it, but for years I turned it over in my mind, and it always made me uneasy” (private note, published in T. R. Henn, The Lonely Tower: Studies in the Poetry of W. B. Yeats [1950], 291). But even in Johnson’s remark we find hauteur and hyperbole rather than the flippant coldness of the author of Hell? Yes!, let alone the sadism and resentment Gibbon condemned in Tertullian’s catalogue of pagans groaning in darkness and liquefying in fire—to say nothing of his other “unfeeling witticisms” at the expense, for example, of the tragic poets now burning in hell, who have grown “more tuneful in the expression of their own sufferings.”

There is no dearth of preachers who take an unseemly pleasure in terrifying, or gratifying, their audiences with fire and brimstone. Celebrated theologians, perhaps most prominent among them Jonathan Edwards, have delivered sermons depicting the terrors of the pit of hell to motivate their flocks to repent and be saved. Edwards was, along with the more flamboyant George Whitefield, the key figure in the Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s in America. Speaking softly, he terrified those attending his classic 1741 Enfield sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”:

The pit is prepared, the fire is made ready, the furnace is now hot, ready to receive the wicked! The flames do now rage and glow. The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much in the same way one hold a spider or some loathsome insect, abhors you and is dreadfully provoked. (Works, VII, 499)

And, however intellectually enlightened he may have been, Edwards was an enthusiastic advocate of the abominable fancy. The “view of the misery of the damned,” he proclaims in an April 1739 sermon, “will double the ardor of the love and gratitude of the saints in heaven,” for whom the “sight of hell torments will exalt [their] happiness… forever (“The Eternity of Hell Torments”). A close disciple of Jonathan Edwards, Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803), though a humanitarian activist motivated by disinterested benevolence (indeed, an opponent of the slave trade who envisioned establishing colonies in Africa for liberated slaves), was rather less humane in contemplating the divine design involving hell, and the psychological as well as retributive purpose it served. He was even more explicit than his mentor Edwards about the suffering—specifically, the eternal suffering—of others being required to maximize the happiness of the blessed:

The display of the divine character will be most entertaining to all who love God, [and] will give them the highest and most ineffable pleasure. Should the fire of this eternal punishment cease, it would in a great measure obscure the light of heaven, and put an end to a great part of the happiness and glory of the blessed. (Works, 458)

Of course, to “all who love God,” there was also a “world of love” awaiting. Jonathan Edwards concluded his 1738 sermon, “Heaven is a World of Love,” by conditionally assuring his listeners, “if ever you arrive at heaven, faith and love must be the wings which must carry you there.” He would seem to be echoing the 1708 prayer of his fellow Congregationalist, Isaac Watts, whose hymns were known throughout Protestant Christendom:

Give me the wings of faith to rise

Within the veil, and see

The saints above, how great their joys,

How bright their glories be.

But Watts was also capable, enthusiastically if less characteristically, of attributing the “joys” of those “saints above” to the Abominable Fancy. The following quatrain comes from a hymn that presumably once fired up, or terrified, congregations, but which is seldom sung these days:

What bliss will fill the ransomed souls,

When they in glory dwell,

To see the sinner as he rolls

In quenchless flames of hell.

And what if the sinners rolling in quenchless flames happen to be the nearest and dearest of the ransomed? When asked if the saved will not be saddened by seeing loved ones tortured in hell, Martin Luther responded, “Not in the least.” And Johann Gerhard, the leading Lutheran theologian of the 17th century, observed that “the Blessed will see their friends and relations among the damned as often as they like but without the least of compassion.” Addressing a series of rhetorical questions—“Can the believing husband in heaven be happy with his unbelieving wife in hell? Can the believing father in heaven be happy with his unbelieving children in hell? Can the loving wife in heaven he happy with her unbelieving husband in hell?”—Jonathan Edwards responded quietly but exuberantly, “I tell you, Yea! Such will be his sense of justice that it will increase rather than diminish his bliss” (Discourses on Various Important Subjects, 1738). In his 1924 collection of essays, The Liberty of Man, Woman, and Child, the “Great Agnostic,” Robert Ingersoll, observed of this repudiation of the familial bond, “There is no wild beast in the jungles of Africa whose reputation would not be tarnished by the expression of such a doctrine.”

J.I. Packer photo by Ron Storer

J.I. Packer photo by Ron Storer

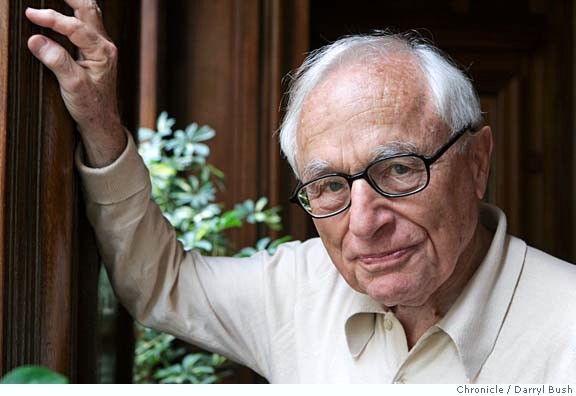

Such heartless theological sentiments persist. As we were recently assured by Canadian minister and theologian J. I. Packer, “love and pity for hell’s occupants will not enter our hearts” (“Hell’s Final Enigma,” in Christianity Today Magazine, April 22, 2002).Two years later, actor Mel Gibson, later notorious for a drunken anti-Semitic rant and various sexual infidelities, surprised an interviewer for the Australian Herald Sun by stating that his wife, Robyn, though “a much better person than I am,” indeed a “saint,” was an Episcopalian, and therefore headed to hell, since he was doctrinally certain that there was no salvation outside the Roman Catholic Church. Gibson, an ultra-conservative Catholic, either didn’t know or didn’t care that the ecumenical post-Vatican II Church had revised the old dogma, extra ecclesiam nulla salus. In any case, as a Catholic, he was going to heaven, from which perch he would ultimately and eternally be looking down on his wife in hell: a woman almost certainly “a much better person” than he—and, in her pre-infernal existence in the temporal world, remarkably well-off, having received 400 million dollars, the largest settlement in Hollywood history, when she divorced Gibson in 2011, less than a decade after he had consigned her to the pit of hell.

That dogma, and the familial heartlessness that turns, in Edwards and others, from wife, husband, and children in the name of theology, was still operative in the late 19th century, when, writing in Spanish, Cuban Archbishop Anthony Mary Claret composed a series of 35 meditations on the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises (translated into English in 1955 as The Golden Key to Heaven). Some meditations are admirable, but in addressing the “Pains of Hell,” Claret noted that “for all eternity,” a condemned “wretch” will be abandoned by friends, without a “kind word.” Rather, “they will be satisfied to see him in the flames as a victim of God’s justice. They will abhor him. A mother will look from paradise upon her own condemned son without being moved, as though she had never known him.”

In my junior year at Fordham, precisely a decade after Archbishop Claret was canonized by Pope Pius XII, we had a retreat that employed Ignatian “composition of place” to evoke the physical and spiritual agonies of eternal punishment: a presentation as graphic and horrifying as the hellfire sermon that sends a terrified Stephen Dedalus scurrying off to confession in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The sustained double-sermon in Portrait (it takes up most of Part III of the novel) was delivered by Fr. Arnall, Joyce’s fictional name for the priest, Fr. James Cullen, who led the actual retreat Joyce attended as a Belvedere College student. In fact as in fiction, the retreat was based on traditional Jesuit sermons. The main text Joyce used was Giovanni Pietro Pinamonte, S. J., Hell Opened to Christians, to Caution Them from Entering into It, first printed in Bologna in 1688, and frequently reprinted in English translations (though fluent in Italian, Joyce used a late 19th-century translation printed in Dublin).

Four Woodcuts from Pinamonte’s Hell Opened to Christians, to Caution Them from Entering into It

Four Woodcuts from Pinamonte’s Hell Opened to Christians, to Caution Them from Entering into It

As I can attest from my own experience, the order, imagery, phrasing, biblical citations, and graphic images to which we were exposed at Fordham in 1960 were virtually identical to the pattern laid down in Giovanni Pinamonte’s uncompromising ur-text, a rhetorical set-piece at once salutary and terrifying. Another model for Fr. Arnall may have been the appropriately-named Fr. Furniss, a sadistic 19th-century Anglo-Irish priest who specialized in terrorizing children with the threat of hellfire. We can catch the flavor of the preaching of both Pinamonte and Furniss in the hell-passages of the sermon in Portrait. Though Fr. Arnall covers in sequence the four “last things, death, judgment, hell, and heaven,” the section of the retreat that struck terror in the soul of Stephen Dedalus, as in mine in 1960, followed the opening of the maw of hell—fusing Pinamonte’s title, Hell Opened to Christians, with the “opening” of the “mouth” of Sheol in Isaiah:

—Hell has enlarged its soul and opened its mouth without any limits—words taken, my dear little brothers in Christ Jesus, from the book of Isaias, fifth chapter, fourteenth verse….

—Now let us try for a moment to realize, as far as we can, the nature of that abode of the damned to which the justice of an offended God has called into existence for the eternal punishment of sinners. Hell is a strait and dark and foulsmelling prison, an abode of demons and lost souls, filled with fire and smoke ….By reason of the great numbers of the damned, the prisoners are heaped together in their awful prison, the walls of which are said to be four thousand miles thick…They are not even able to remove from the eye a worm that gnaws it [echoing, like the coming “stench,” that old favorite, Isaiah 66:24]….They lie in exterior darkness…for the fire of hell, while retaining the intensity of its heat, burns eternally in darkness…

—The horror of this strait and dark prison is increased by the awful stench. All the filth of the world, all the offal and scums of the world, we are told, shall run there as to a vast reeking sewer when the terrible conflagration of the last day has purged the world…Imagine some foul and putrid corpse that has lain rotting and decomposing in the grave, a jellylike mass of liquid corruption. Imagine such a corpse a prey to flames, devoured by the fire of burning brimstone and giving off dense choking fumes of nauseous loathsome decomposition. And then imagine this sickening stench, multiplied a millionfold and a millionfold again from the millions upon millions of fetid carcasses massed together in the reeking darkness, a huge and rotting human fungus. Imagine all this and you will have some idea of the horror of the stench of hell.

But more and worse was to come: namely, the pain, intensity, and eternity of the fire “created by God to punish the unrepentant sinner”—a litany of tortures that out-Dantes Dante. Earthly fire consumes itself,

but the fire of hell has this property that it preserves that which it burns and though it rages with incredible intensity it rages for ever….The blood seethes and boils in the veins, the brains are boiling in the skull, the heart in the breast glowing and bursting, the bowels a redhot mass of burning pulp, the tender eyes flaming like molten balls…And the strength and quality…of this fire is as nothing when compared to its intensity, an intensity which it has as being the instrument chosen by divine design for the punishment of soul and body alike. It is a fire which proceeds directly from the ire of God, working not of its own activity but as an instrument of divine vengeance….Every sense of the flesh is tortured… and through the several torments of the senses the immortal soul is tortured eternally in its very essence amid the leagues upon leagues of glowing fires kindled in the abyss by the offended majesty of the Omnipotent God and fanned into everlasting and ever increasing fury by the breath of the anger of the Godhead.

Fr. Arnall concludes by praying “fervently to God that not a single soul of those who are in this chapel today…may ever hear ringing in his ears the awful sentence of rejection: Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels!” (Portrait, 119-24).

.

4

The emphasis of our retreat-master at Fordham was, as with Fr. Arnall, on repentance and salvation. But even their final prayerful citation of Jesus (Matt 25:41) intensified rather than alleviated the terror of being cast into “the everlasting fire.” There was nothing merely figurative about our preacher’s detailed descriptions of the myriad torments of hell, and, though I knew nothing in 1960 of Pinamonte or Furniss, it was sometimes hard to separate the tone and sensuous immediacy of our priest’s Jesuit rhetoric from the vindictive glee of Tertullian relishing the agonies of the damned.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Shortly after I graduated from Fordham, in 1961, I read Nietzsche seriously for the first time. I had earlier responded to the excitement of his literary style and to what W. B. Yeats described with remarkable tonal accuracy as this “strong enchanter’s curious astringent joy.” But in reading On the Genealogy of Morals, arguably the most substantial of his works, I discovered that Nietzsche had responded to the very passages in Aquinas and Tertullian that had so troubled me a few years earlier at Fordham. Quoting both passages in Latin, Nietzsche attributed their sadism—as expressed particularly by that “enraptured visionary,” triumphalist Tertullian—to what he repeatedly condemns (always in French) as the ressentiment characteristic of “slave morality”— here, future “blessedness” as Will to Power in disguise (Genealogy of Morals 1:15). Gibbon’s image of oppressed Christians “seduced…by resentment and spiritual pride to delight in the prospect of their future triumph,” may have helped generate Nietzsche’s crucial concept, first announced in Beyond Good and Evil §260 and fully developed in the Genealogy, of ressentiment as the driving impulse of “slave morality”: the desire of the weak, the “good”, for vengeance against the strong, depicted not merely as “bad,” but “evil.”

The dubiousness of the doctrine of eternal punishment of those condemned as “evil,” let alone the appalling notion that, far from eliciting empathy, their suffering is a source of glee for the saved, becomes even more repugnant when that pleasure is extended from his creatures to the Creator himself. Some Christians claim that the bliss of the saints, enhanced by looking down on the suffering of the damned, is shared by God—as we just saw in quoting Joyce’s version of the standard Jesuit retreat-sermon as well as the sermons of Jonathan Edwards and his disciple Samuel Hopkins. Whatever the values of its spiritual revival, its influence in effecting social reforms, and its often splendid rhetoric, the Great Awakening seems to me more of a Great Nightmare. The God of Jonathan Edwards, whether the “angry God” who abhors the sinners he holds in his hands, or the “just” God who presides over a system in which the happiness of a father who has made it to heaven is increased rather than diminished by the sight of his “unbelieving children in hell,” is obviously a God to fear, but hardly one we would wish to love or to be coerced into worshiping.

I have in mind the conclusion of John Stuart Mill’s Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy (1865), a book more revealing of Mill’s own philosophy. Putting aside the “glad tidings” of Jesus, Mill aligns himself with Hamilton in denying any “immediate intuition of God.” But some claim that the “infinite goodness ascribed to God” is not “the goodness we know and love in our fellow-creatures distinguished only as infinite in degree,” but is, rather, “different in kind and of another quality altogether.” In concluding, Mill, risking hellfire, defiantly rejects this God of transcendent, ineffable morality in the name of the highest form of morality among human beings, fellow-creatures with whom we interact ethically, compassionately, and, at our best, with love. “If,” Mill writes, “I am informed that the world”

is ruled by a being whose attributes are infinite, but what they are we cannot learn, except that the highest human morality does not sanction them—convince me of this and I will bear my fate as I may. But when I am told that I must believe this, and at the same time call this being by the names which express and affirm the highest human morality, I say, in plain terms, that I will not. Whatever power such a being may have over me, he shall not compel me to worship him. I will call no being good who is not what I mean when I apply that epithet to my fellow-creatures; and if such a being can sentence me to hell for not so calling him, then to hell I will go. (Works, ed. John M. Robson (1963-1991), 10:103.

Of course, human beings are not always “good.” We can, though it would fly in the face of centuries of Christian tradition, dismiss the notion (hardly restricted to Puritan or Jesuit hellfire sermonizing) of an angry and vindictive deity as an anthropomorphic projection, a reflection of human rather than divine cruelty, sadism, and ressentiment. And it is true that, in what Nietzsche called “these more humane ages,” most Christians, other than rigid traditionalists and literalist fundamentalists, think and speak less of a God of Wrath than of Love, and of hell (as even Billy Graham thinks) as separation from God rather than a literal “place.” Against the Great Awakening of Edwards and Whitefield may be set a more significant awakening: the dawning of the American Enlightenment, best personified by those two once-bitter political rivals and later great friends among the Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. “I can never join Calvin is addressing his God,” wrote the deist Jefferson to Adams:

He was indeed an Atheist, which I can never be….If ever a man worshipped a false God, he did. The being described in his 5 points is not the God whom you and I acknowledge, the creator and benevolent governor of the world; but a daemon of malignant spirit. It would be more pardonable to believe in no God at all, than to blaspheme him by the atrocious attributes of Calvin. (17 April 1823)

My friend Paul Johnston recently quoted an observation, made five years earlier, by this letter’s recipient. Writing on 14 September 1818 to Jefferson, Adams attacked reliance on miracles and prophecies, the idea of a vain and vengeful deity, and the awful belief that most of humankind is eternally doomed to Hell. He also offered a personal, rational and humane definition of what he believed it meant to be a Christian:

We can never be so certain of any prophecy, or of any miracle…as we are from the revelation of nature, that is, nature’s God….Can prophecies or miracles convince you or me that infinite benevolence, wisdom, and power created, and preserves for a time, innumerable millions, to make them miserable for ever, for his own glory? Wretch!…Is he vain, tickled with adulation, exulting and triumphing in his power and the sweetness of his vengeance? Pardon me, my Maker, for these awful questions. My answer to them is always ready. I believe in no such thing. My adoration of the author of the universe is too profound and too sincere. The love of God and his creation—delight, joy, triumph, exultation in my own existence—though but an atom, a molecule organique, in the universe—these are my religion. Howl, snarl, bite, ye Calvinistic, ye Athanasian divines, if you will. Ye will say I am no Christian. I say ye are no Christians.

After so much hellfire and rejoicing at its torments, we can find respite in the refreshingly unorthodox voice of Enlightenment Reason, blasphemous though it may be to traditionalists. The deist sobriquets for God, civic and civil, have, in contrast to the sound and fury of sectarian conflict and theological hairsplitting, a euphemistic charm. Momentarily setting aside the angry God and loving but wrathful Jesus of historical Christianity, we can join Jefferson in acknowledging the “benevolent governor of the world,” just as we share Adams’s exultation in his own existence, and appreciate his love of the benign “author of the universe.”

Baruch Spinoza by Franz Wulfhagen

Baruch Spinoza by Franz Wulfhagen

Jefferson’s insistence on intellectual and democratic freedom from a tyrannous religion, like the skepticism of Adams regarding the reality of “miracles” and his reinterpretation of the nature of “prophecy,” are aligned for me with the earlier and even more profound enlightenment provided by an Amsterdam Jew writing in the 17th-century Dutch Republic: the great Baruch (Benedict) Spinoza. Despite being expelled from his synagogue and condemned as an atheist, Spinoza proved to have immense appeal, exerting an influence that crossed sectarian divisions. Fervently and famously embraced as a “god-intoxicated man” by the German Catholic Romantic poet Novalis (Friedrich Hardenberg) and—by the English Romantic poets Coleridge and Wordsworth—as a pantheist for whom Nature was indistinguishable from God, Spinoza was also profoundly admired by the atheist Nietzsche, an opponent of all other Idealist philosophers, who rightly venerated Spinoza for his simple and sublime nobility of spirit. As did Einstein, who, because of the “God-talk” in which he expressed his sense of awe and wonder in contemplating the beauty, majesty, and ultimate mystery of the universe, was mistakenly thought, by American admirers in his adopted country, to be a believer in a personal God, one who intervened in human affairs and was accessible by prayer. No, explained Einstein, his “religion” was limited to reverence of the order (since “God did not throw dice”) of the cosmos itself, and his only deity was “Spinoza’s God.”

The first serious philosophy paper I wrote at Fordham was on Spinoza’s Ethics, and I still remember that my Jesuit professor, in grading the essay A+, added a remark more gracious than accurate: that I was “farther along than he on the via illuminativa.” But the work of Spinoza I later wished I’d focused on at Fordham was the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670), an immensely influential treatise pioneering the argument that the Bible, written by prophets of superior ethics but vivid imaginations, was not to be read “literally.” Authentic religion had nothing to do with “miracles and prophecies,” church authorities, or divisive sectarian dogma. Instead, “true religion” was based on the moral imperatives to seek the truth, to love one’s neighbor, and to be tolerant. The book’s political chapters, as far in advance of their time as those on theology, were a sustained plea for democratic toleration, especially in defense of “the freedom to philosophize” without interference from religious or political authorities.

For such thoughts, Spinoza was driven from his synagogue in the harshest terms. The cherum (or ritual of expulsion and ostracism) reads in part: because of his “abominable heresies” and “monstrous deeds,” we “excommunicate, expel, curse, and damn Baruch Spinoza, with the consent of God and with all the curses…written in the Book of the Law.” The vicious backlash against the Treatise also came from Christians. Within weeks of its publication, it was denounced by a prominent German theologian as “a godless document” that should be banned in every country. One of Spinoza’s Dutch countrymen described it as an “atheistic book full of abominations…which every reasonable person should find abhorrent.” Another, not to be outdone, called the deeply moral and eminently reasonable Tractatus “a book forged in hell,” written not by the ethical thinker toiling as a lens-grinder in Amsterdam, but by the devil himself.

In short, before and after welcome bursts of Enlightenment, Dutch or American, there remains a long, problematic, and continuing history of religious intolerance and induced terror. Despite being surrounded by and taught by smart and compassionate Jesuits, and despite (perhaps because of) the fact that I was in the advanced theology course, and attended that terrifying retreat, I have always found it difficult, after those impressionable years at Fordham, to glibly dismiss the concept of the vengeful deity fearfully accepted, or sadistically embraced, by so many believers for so long. And, like it or not, and however softened or “symbolic” much non-fundamentalist Christianity has become in these “more humane ages,” the doctrine of eternal punishment—and the concept of a God willing to initiate, approve, and even occasionally take relish in such monstrous cruelty—has defined traditional Christian theology for most of its history.

The widespread phenomenon often described as the “decline” or even “disappearance” of hell—a trickle in the 17th century, a stream in the American Enlightenment (including the Divinity School Address of Emerson), and cresting in England and continental Europe in the later 19th century, first among Protestants, somewhat later among Catholics—is, taken as a generalization, a historical fact. But while hell’s heat has been lowered, its flames a mere flicker in comparison to their former raging in incendiary hellfire texts and sermons, the old time religion is still alive and well, among some televangelists, and in much of Bible-belt contemporary America.

As for Catholicism: A tonal and gestural sea-change has recently occurred. The election of Pope Francis, an Argentina-based Jesuit, signaled a dramatic double-shift: from Eurocentrism and from dogmatic harshness to compassion and tolerance. That shift seems decisive, but is it permanent, and how far can tone take us in tempering let alone altering doctrine? It was, after all, just seven years earlier that Francis’s conservative predecessor, Benedict XVI, strenuously reaffirmed traditional Church teaching on hell. Benedict’s own predecessor, John Paul II, had referred to damnation vaguely as an “eternal emptiness.” Reacting to the “decline of hell,” especially in Western Europe, Benedict complained that the place of everlasting torment was no longer much talked about. He went on to describe Satan as a “real, personal and not merely symbolic presence” and proclaimed that hell, far from being a mere state of mind, or a condition of separation from God, is an actual place, one that “exists and is eternal.” We were spared fire-and-brimstone details, but listening to this March 2007 proclamation on the radio, I was transported back almost a half-century to that Fordham retreat.

Having lost my faith while remaining fascinated by the figure of Jesus, attractive despite his apparent consignment of most of humankind to eternal punishment, I sometimes want to cry out with the boy’s father in Mark 9:24: “Help thou my unbelief.” But the theological Problem of Suffering goes beyond the posthumous torments of hell to pain right here on earth, with the undeserved suffering of the innocent presenting the single greatest challenge to my own ability to “believe” in a God simultaneously omnipotent, omniscient, and all-loving. As David Hume has “Philo,” the more skeptical of his two spokesmen, note in Part 10 of his posthumously-published Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779), “Epicurus’ old questions are yet unanswered”—questions we may apply to the presence of evil and suffering in a world “groaning” for “deliverance” (Rom 8:19-22), or to the groaning of hopeless souls in hell. Simplifying Epicurus, Hume has Philo ask, “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then cometh evil? (75).

Nothing I read in Augustine or Aquinas about God’s “justice,” or about the constrained freedom that makes eternal punishment the “choice” of sinners, enabled me to answer those questions. And my subsequent immersion in the pornography of the Abominable Fancy only deepened my alienation from the faith I was raised in, and problematized the beliefs I had brought with me as a Freshman entering Fordham. Beginning college was hardly the time to abandon reason; and, in fact, as my classmate and lifelong friend Bill Baumert has often noted in retrospect, we received a first-rate and rigorous education at Fordham—far superior to what generally passes as education these days at colleges and universities where the canon has been “exposed,” the curriculum softened, and demands on students drastically eased, as their prose deteriorates, tuition costs soar, and the party goes on.

But I’ve also had other thoughts in retrospect. Being shocked into intellectual as well as emotional resistance by my reading of that fateful passage in Aquinas, I may have betrayed my own growing commitment to the Romantic poets by embracing a too-narrow intellectualism when it came to theology. Not that I was willing, then or now, to honor Imagination by a descent into irrationalism, any more than the great Romantics did. Neither, for that matter, despite some of the words by which we best remember them, did Luther (for all his distrust and frequent condemnation of “that whore, reason”), nor even Tertullian, the passionate evoker of that circus-scene in which Christians would posthumously join him, exulting in the spectacle of pagans writhing in hellfire. Tertullian is even more famous for having said he “believed because it was absurd,” but it isn’t quite that simple.

In arguing, in de Carne Christi 5:4, that the resurrection of Christ’s body, crucified and buried, was certain because impossible [credibile est, quia ineptum es, et sepultus resurrexit, certum est, quia impossibile]—Tertullian may not have been relying on blind faith (the fideism of the oft-misquoted tag, credo quia absurdum est), but following, as James Moffatt suggested a century ago, “in the footsteps of that cool philosopher Aristotle” (Journal of Theological Studies 17 [1915-16], 170-71). Since, in lines he quotes from the tragedian Agathon, “what is contrary to probability sometimes occurs,” it can be argued, says Aristotle, that “the improbable will be probable” (Rhetoric 2.24.9); even that some stories are so improbable that it can become reasonable to believe them. For Tertullian, the most improbable story is that of the incarnate, crucified, buried, and risen Jesus—which is, paradoxically, what makes it credible. This is the very point made by Shakespeare’s Hippolyta in an exchange in the final act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a riposte to her soon-to-be husband, Theseus, that would have delighted Agathon and Tertullian—and, perhaps, Aristotle.

In the opening of that final act, Theseus, a self-assured rationalist, dismisses (“more strange than true”) the lovers’ tales of their adventures in the moonlit wood. They are “fantasies, that apprehend/ More than cool reason ever comprehends,” and thus to be grouped indiscriminately with the merely imaginary constructions common to “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet.” But we in the audience know to be “true” what Hippolyta shrewdly intuits: that however individually fantastic the tales may be, they are part of an over-all consistency that makes each of them credible. To Theseus’ cool skepticism and reductive characterization of “imagination,” she responds:

But the story of the night told over,

And all their minds transfigured so together,

More witnesseth than fancy’s images

And grows to something of great constancy,

But howsoever strange and admirable. (5.1.23-27)