X

This is a photograph of me at about two years of age. I have been looking at this picture for the past year or so, while I was working on a collaborative essay, a chapter on twentieth-century fashion in literature. It was impossible for me to reread so many early twentieth-century books without thinking of my own mother, and her clothes and the way in which clothing was a bond between us. My mother was always fashionable, and briefly was a model for Max Factor, while she was freelancing as a journalist in the first years of her marriage, before I was born. My father was fat, very fat, as you can see, and was very lucky to have her. She is chic in her slender yellow dress, appliqued with brown velvet leaves on the chest. Her hair partially rolled in a chignon. Two things strike me about my role in this picture. I am dressed, as I was for years, in a handmade dress, this one with sweet cross-stitching. I seem oblivious to my clothing, although that might not be true. And of course my stuffed animal is a horse, which resonates with the fact I have written many poems about horses, including an entire book, Sea Horses, about the wild horses of Sable Island. Was my identity being forged even then by my dress and my accessory, a stuffed horse?

The author in crepe dress, with stuffed horse, 1942-44

The author in crepe dress, with stuffed horse, 1942-44

My youngest brother David has, by default, become a sort of archivist of the family photographs. He observes that most of the pictures in the nuclear family collection were of me. I am the eldest of four siblings and the only girl. Is the preponderance of pictures of me because I am a girl? Because girls get dressed in pretty dresses? Because I am pretty? Because I was first born? These are all seemingly innocuous and even commonplace questions. But what do they mean?

“[M]ost of the pictures in the nuclear family collection were of me.”

“[M]ost of the pictures in the nuclear family collection were of me.”

Like many women of her generation, my very beautiful and intelligent mother was an excellent seamstress. And so she dressed me, made my clothes, as a baby and a little girl. That stopped when I was an awkward and highly emotional teenager. Then, eventually, I had part-time jobs, and began to buy inexpensive and standard clothes for myself: saddle shoes, poodle-cloth skirts, white sharkskin blouses. But when I got my first real job, as a teacher in a university, my mother spent months with me going to the fabric mills, just east of Kitchener-Waterloo, and then making me suits and dresses, some from elaborate Vogue patterns. Was this because I was gainfully employed and needed to present a professional appearance, or was it because I became beautiful for the first time since I was a little girl? Now I could be a brooch on my mother’s lapel. Or, as Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own remarked, women are the looking glasses who enlarge men at twice their size. Did I become again, perhaps for the first time since childhood, the looking glass enhancing my mother, after such a long wait?

The author’s mother

The author’s mother

Here is a photograph of me at the age of 13, with my adored baby brother David on my lap. I am wearing a sharkskin blouse and a poodle-cloth skirt. David is too young to worry about how I look, to wonder whether I am pretty, or why I am not as pretty as the other girls in our small town. He loves me because he knows I love him passionately and I spend all my waking hours thinking of him, rushing home from school to take him for walks, feeding him, changing his diapers, even sharing the bed with him and his many stuffed animals.

The author, age 13, with baby brother David

The author, age 13, with baby brother David

Here is a photograph of David sixty years later. His expression is the same, although now, like our father, he is wearing a suit and tie.

The author’s brother David, 60 years later

The author’s brother David, 60 years later

In the first few years of my teaching, and my brief marriage, I too began to sew. Sew independently, of my own volition, that is. Of course I had to take Home Economics in high school, although I had asked to take Shop, and sewing was part of the Home Economics curriculum. Most of my sewing, and my knitting, I took home to work on, which really meant that my mother could rip it out and redo it and advance a bit on it for me for the next day. I certainly learned to vacuum and to make tomato juice from scratch, and to embroider tea towels, all activities I have not continued. However, when I came of age the hippie era had begun. I began to sew kaftans, my mother was making macramé jewelry, and I began to sell my work and my mother’s in the various head shops, like Tribal Village, which sprang up in the city. I put away my Vogue pattern-St. Laurent suits, and my bra, and followed the trend, vintage clothing, much from my mother’s wonderful stock of 1940s and 1950s coats and outfits from Creed’s, an elegant high-end Toronto store, and 1920s and 1930s dresses from London’s vintage shops in Chelsea and the Portobello Road markets, and from my friend Mary Fogg’s Oxfam shop in Reigate, Surrey.

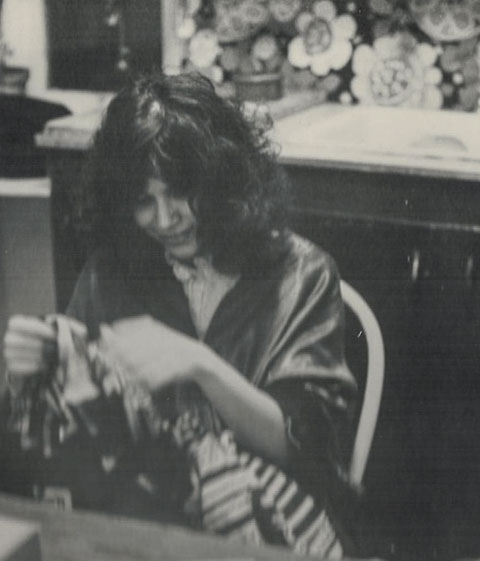

Here is a picture of me in a luminous green robe trimmed with fake fur, made for me by my mother. I am sewing a kaftan, the fabric featuring an overall geometric silver design, intended for sale at a local head shop.

The author sewing a kaftan, 1974

The author sewing a kaftan, 1974

Young designers had begun to open shops in Toronto, and in London, England, in Chelsea and High Street Kensington. Those clothes too were part of my wardrobe, clothes from The Unicorn, and Dr. John’s and the Poupée Rouge in Toronto, and from Biba’s in London and from Ossie Clark.

Toronto wasn’t as swinging as London, with its mod wear for men, but Toronto did have several designers’ shops in Yorkville, on Cumberland and on Yorkville and on Bellair, and even on Avenue Road, and in the Village on Gerrard Street, and in Honest Ed’s Village on Markham Street. And the city was buzzing with the marvelous energy brought to it by the American draft dodgers. Clothing became fun, and a direct expression of the sexual revolution.

I got married in London in Trafalgar Square in St. Martin-in-the-Fields, in a Unicorn orange velvet dress, its hood and hem trimmed in red fox fur. My husband wore a black velvet suit and my brother Robin, who was best man, wore one in green velvet.

There are few photographs of me in this period in these clothes; in many I am naked, as befits the sexual revolution, but here is one where I am wearing an outfit from Dr. John’s on Gerrard Street, a grey jersey top and short grey flannel skirt with gored panels in it, topped by a fake suede vest which I had sewn myself. The rather rough stitching on my vest might or might not have been intentional.

The author wearing an outfit from Dr. John’s (photo by Jay Cohen)

The author wearing an outfit from Dr. John’s (photo by Jay Cohen)

“I am naked, as befits the sexual revolution…”

“I am naked, as befits the sexual revolution…”

So my life as a student and a teacher of literature has been from the beginning intertwined with my changes in costume and with the way in which my clothes not only signaled my identity, but also were active in its construction.

I remember even as a young graduate student visiting my parents and putting on fashion shows with my mother for my father as he sat in his armchair reading the daily newspapers. It never occurred to me then that this might be an unusual activity. While some graduate students were attentive to what characters in novels were eating, the boeuf en daube, for example, that Mrs. Ramsay serves for dinner in Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, I was more interested in what the characters were wearing.

When I look again at that early picture of myself with my parents, I notice my father’s green tweed suit and his paisley tie. It is a uniform, one commonplace enough since suits became standard for menswear, after what culture critics have called the “Great Male Renunciation” in the nineteenth century. What this rather rotund phrase acknowledges was the fact that men had stopped wearing high heels and elaborate and luxurious clothing, including voluminous lace cuffs and powdered wigs as well, for a sort of uniform which has more or less persisted through the twentieth and even into the twenty-first century. Swinging Chelsea and the Haight-Ashbury hippie era and punk culture being notable exceptions.

Although my father was always rather formally attired, including English brogue shoes, shirts and ties, as was his generation, he did express himself in his choice of headgear. Here he is in a straw hat, dancing with one of my brother Robin’s girlfriends…

The author’s father dancing in straw hat, 1980

The author’s father dancing in straw hat, 1980

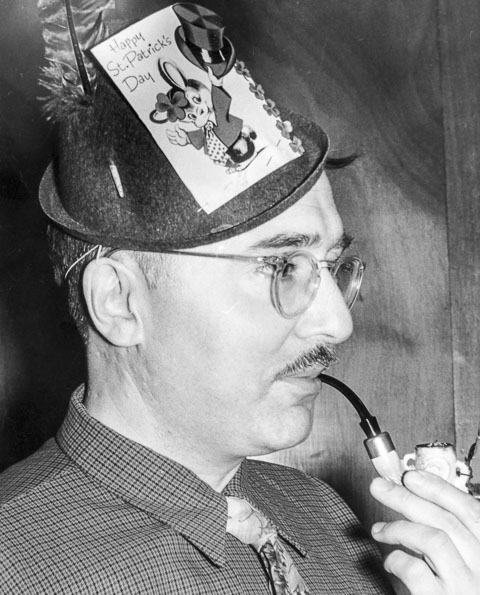

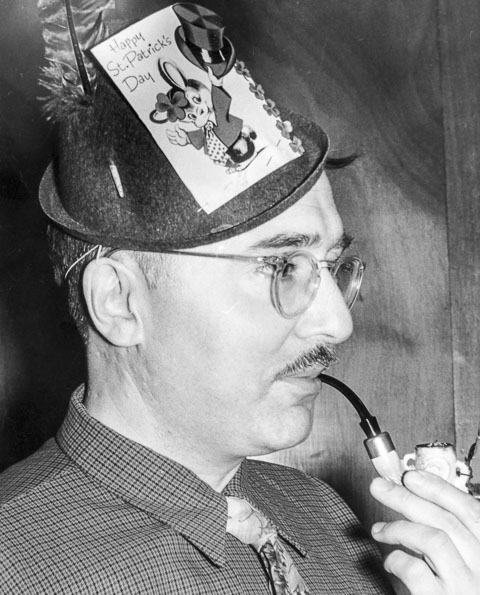

…and here he is celebrating St Patrick’s Day, with a hat of his own devising. He did enjoy costume opportunities.

The author’s father in St. Patrick’s Day hat

The author’s father in St. Patrick’s Day hat

In this picture, he appears to be walking a catwalk. He has an audience and is prancing in his shorts. My father often wore shorts in the summer time when he drove into Toronto to do film bookings for his cinema. He considered the wearing of shorts in the city to be a bit rebellious and in line with some aspects of his character. He also wore an Odd Fellows Lodge ring, although he never belonged to the Odd Fellows Lodge.

The author’s father parading in shorts, with cigar

The author’s father parading in shorts, with cigar

General male sobriety in clothing highlights profoundly the moment in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) when Daisy and Gatsby gather at his two wardrobe cabinets, where his shirts are “piled like bricks a dozen high . . . shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel . . . shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange, and monograms of Indian blue” and Daisy begins to weep at the beauty of his many different coloured shirts.

Shirts seem to be essential masculine garb throughout the twentieth century. As a teenager I remember well ironing and folding my father’s shirts. This was a task I enjoyed and the smell of them while ironing and then the folding them gave me great satisfaction. My father wore a fresh shirt each day and had a chest of drawers, a highboy in green lacquer, built in the art deco style, something like a pyramid, dedicated to their storage.

Unlike my father’s shirts, however, Gatsby’s shirts signal his immense wealth and therefore his attractiveness. Clothing has always been a crucial signifier. The literary depictions of women’s clothing in the first half of the twentieth initially signal primarily their class, often their age, and eventually their occupation, as the roles of women, and the presence of women in the workplace, change.

In erotic fiction, of course, little changes, as the fewer the clothes, the more so-called “erotic” the portrait. When I was a graduate student everyone was reading Pauline Réage’s wildly popular novel, The Story of O (1953), which could be considered the standard for women engaged in erotic behaviour, a short skirt, no underwear, long gloves, and, in cold weather, some sort of fur coat. By the end of the twentieth century, underwear becomes outerwear, as Madonna’s Sex (1992) book amply illustrates. The question of undergarments is in itself of some interest, since, except for nightgowns, very little of these essentials make a fictive appearance.

When I began to teach in the late 1960s, there was a major shift in Western clothing and some of these shifts appear in well-known authors. The hippie movement, the rise of feminism, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury and London’s Chelsea, all see male and female clothing coming closer to one another, as do hairstyles in general. The punk movement of the 70s in a sense repeats this trope, as girls dress like boys, and a little bit contrariwise. I remember when I was working on a project centred on the Palais Royale in Paris wandering through its garden and being delighted at spying a young man in a sarong topped by a tweed sports coat and shirt and tie. He turned out to be a clerk in the Jean Paul Gaultier shop nearby. Returning to London, I noticed for the first time in Chelsea men also wearing skirts with sports jackets.

The author wearing a man’s cap, 1974-75

The author wearing a man’s cap, 1974-75

For the next twenty years or so, the reverence for couture, and the use of dressmakers who might imitate couture, also begins to erode, as fashion is democratized, male and female clothing blends, and branding takes priority, initially as a reaction to democratization. The wide availability of high street knock-offs of expensive runway creations does mean that authentic luxury brands are increasingly valued as signs of status, and their logos are worn on the outside of many garments and accessories. However, a proliferation of copies of luxury brand items, both labels and logos, ensues, and all attempts to police and patent couture and luxury design, while continuing into the twenty-first century, are more or less ineffective.

As television and film become primary channels of expression for clothing as iconic, I think a good case might be made that literature turns inward, the interior life of characters becomes central, and their external appearances, and particularly their clothing, play little part in who they are and what they do. This was a shift signaled as early as 1924 by Virginia Woolf in her pamphlet “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” where she argues against stressing the fabric of things in order instead to depict human nature. The interior life, argues Woolf, is what the novelist should focus on.

A classic and spectacular example of the rise of couture in popular media is Martin Scorsese’s The Gangs of New York (2002)—loosely based on Herbert Asbury’s 1927 nonfiction book The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld—where the gangsters are dressed brilliantly and memorably; male clothing dominates the screen. The costume design won an Oscar award for British costume designer Sandy Powell. The cut of the male costumes seems to reference the men’s wear of Italian designer Giorgio Armani, who has himself designed clothes for more than two hundred films including American Gigolo, The Aviator and The Wolf of Wall Street. By 1981, Giorgio Armani had become the rock star of fashion, appearing on the cover of Time magazine. Scorsese’s own father was a clothes presser, so Scorsese’s emphasis on male clothing and fashion in the film, about to be a TV series, has intriguing autobiographical roots.

My own return to designer clothing began about this time in the late 1970s–early 1980s. I was earning a living as a lecturer, and I was constantly in the public eye. Japanese and Italian designers were shaking up the runways in Paris.

The use of actors, and most often actresses, in advertisements for major luxury fashion companies in the later twentieth century, shows just how much fashion and clothing have become an important component of the commercial presentations of self, linked to class and prestige. Not that this is new, but the use of models whose financial lives are made by impersonations, in essence improvisational identities, does emphasize the importance of clothing in the construction of the public self.

In the nineteenth century, descriptions of the wearing of used clothing, what we call vintage, seemed to be confined to rent girls, who rented attractive clothes in order to sell their bodies. In the later twentieth century vintage carried with it a number of charges, a turning away from the contemporary, from luxury, from commodity culture, but also a way of taking on the past in all its guises. A deliberate looking backward, with the freedom that this engenders.

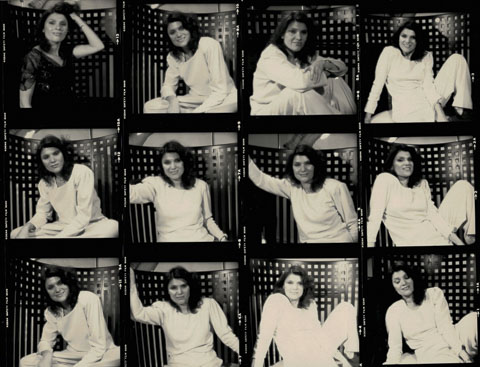

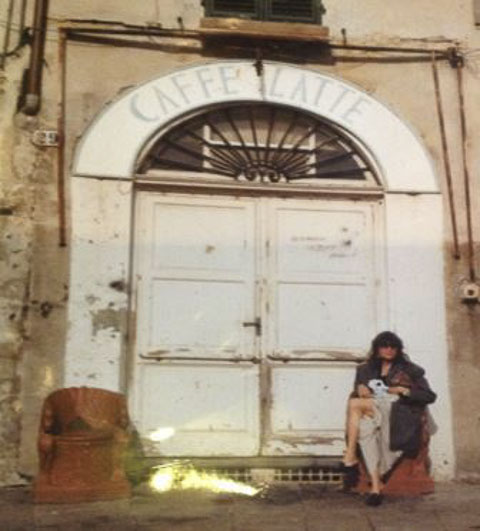

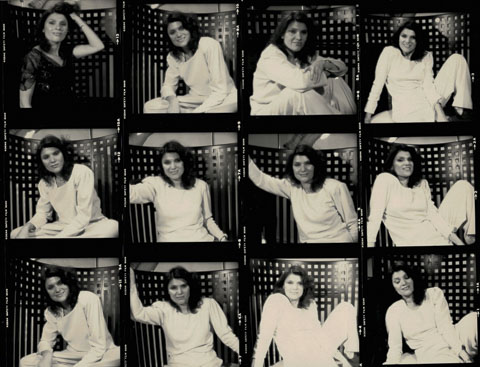

Here is a late-1970s photograph of me, taken by photographer Michel Verreault, in a vintage lace dress from the 1930s. This dress was given to me by my mother, although it is not a dress she ever wore. She had simply collected it as an antique.

Photos of author by Michel Verreault, 1980

Photos of author by Michel Verreault, 1980

Although my doctoral dissertation finally was on William Blake’s illustrations, I spent several years in graduate school working on what is known as modernism. Two modernist writers who had a major impact on my own sense of costume were D.H. Lawrence and Djuna Barnes. In both writers the putting on of costume is a colourful putting on of identity. Each frames a scene and sets it up as in a painting. Each uses colour as well as texture to convey class, emotion, and occupation. Each has a direct relationship to the world of painting—Lawrence was an exhibited painter, and Barnes had studied at the Pratt Institute.

X

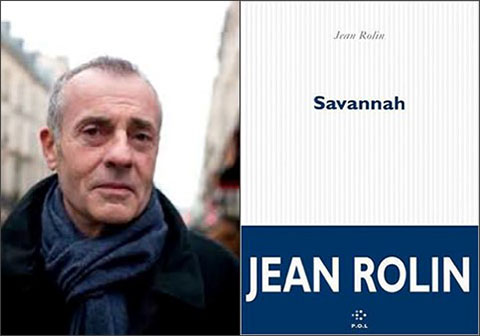

D.H. Lawrence (1885–1930)

The body and its clothing are crucial tropes in Lawrence’s work. In the opening chapter of Women in Love, “Sisters,” Gudrun stands out from the ashy, dark Midlands colliery town to which she has returned from art school and her life in London:

The sisters were women. Ursula twenty-six, and Gudrun twenty-five. But both had the remote, virgin look of modern girls, sisters of Artemis rather than Hebe. Gudrun was very beautiful, passive, soft-skinned, soft-limbed. She wore a dress of dark-blue silky stuff, with ruches of blue and green linen lace in the neck and sleeve and she had emerald-green stockings. Her look of confidence and diffidence contrasted with Ursula’s sensitive expectancy. The provincial people, intimidated by Gudrun’s perfect sang-froid and exclusive bareness of manner, said of her: “She is a smart woman.” She had just come back from London, where she had spent several years, working at an art-school, as a student, and living a studio life. (page 4)

D. H. Lawrence

D. H. Lawrence

The girls, whom Lawrence in this passage casts as incarnations of Diana, Goddess of the Hunt, walk by rows of dwellings of the poorer sort: everything is ghostly. “Everything is a ghoulish replica of the real world, a replica, a ghoul, all soiled, everything sordid.” Gudrun is aware of “her grass-green stockings, her large grass-green velour hat, her full soft coat, of a strong blue color. . . .‘What price the stockings!’ said a voice at the back of Gudrun. A sudden fierce anger swept over the girl, violent and murderous.” (pages 8–9)

The sisters are both school teachers, and Ursula will become involved with a school inspector Rupert Birkin, while her sister Gudrun will become the lover of Gerald Crich. When Gudrun first sees Gerald (page 11) we are told he was “almost exaggeratedly well-dressed.” But no details of his clothing are given. His mother is described as wearing a sac coat of dark blue silk and a blue silk hat (page 11). In this scene at the church we first see Hermione Roddice, a friend of the Criches. Hermione is the wealthy daughter of a baronet; she is Rupert Birkin’s long-time lover, and a woman of intellect and culture:

Now she came along, with her head held up, balancing an enormous flat hat of pale yellow velvet, on which were streaks of ostrich feathers in natural and grey. She drifted forward as if scarcely conscious. . . . She wore a dress of silky, frail velvet, of pale yellow color, and she carried a lot of small rose-colored cyclamens. Her shoes and stockings were of brownish grey, like the feathers on her hat. . . . ( pages 11-12)

Lawrence compares her to a woman in one of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings with her heavy hair and long pale face, and drugged look.

Later, at the school, Hermione appears “a vision . . . seen through the glass panels of the door” (“Class-Room,” pages 34-35). She has come for a surprise visit, while Birkin is giving instruction about the sex life of plants. She speaks in a “low, odd singing fashion”: Her manner is intimate and half bullying:

She was a strange figure in the class-room, wearing a large, old cloak of greenish cloth, on which was a raised pattern of dull gold. The high collar and the inside of the cloak was lined with dark fur. Beneath she had a dress of fine lavender-colored cloth, trimmed with fur, and her hat was close-fitting, made of fur and of the dull green-and-gold figure stuff. She was tall and strange, she looked as if she had come out of some new bizarre picture.

In a scene in a London café, “Crème de Menthe” (chapter 6), where artists gather, an artist’s model called “Pussum” Darrington presents herself :

At Birkin’s table was a girl with dark, soft, fluffy hair cut short in the artist fashion, hanging level and full almost like the Egyptian princess’s. . . . She had beautiful eyes, dark, fully opened, hot, naked in their looking at him. . . . She wore no hat in the heated café, her loose, simple jumper was strung on a string round her neck. But it was made of rich peach-colored crepe-de-chine, that hung heavily and softly from her young throat and her slender wrists. ( pages 60-63)

The architecture and the setting of “Breadalby” ( chapter 8), Hermione’s family home, also provide a frame for dramatic presentations: “Breadalby was a Georgian house with Corinthian pillars, standing among the softer greener hills of Derbyshire, not far from Cromford.” ( page 82)

As Ursula and Gudrun arrive the house appears “like an English drawing of the old school . . . women in lavender and yellow moving to the shade of the enormous, beautifully balanced cedar tree.” ( page 83)

Hermione takes in the two sisters’ appearance:

She admired Gudrun’s dress more. It was of green poplin, with a loose coat above it, of broad, dark-green and dark-brown stripes. The hat was of a pale greenish straw, the color of new hay, and it had a plaited ribbon of black and orange, the stockings were dark green, the shoes black. It was a good get-up, at once fashionable and individual. Ursula, in dark blue, was more ordinary, though she also looked well.

Hermione herself wore a dress of prune-colored silk, with coral beads and coral colored stockings. But her dress was both shabby and soiled, even rather dirty.

To entertain themselves the various characters form Biblical tableaux of Naomi and Ruth and Orpah, in the fashion of the Russian Ballet of Pavlova and Nijinsky, with a panorama of costume and emotion. (page 92)

As they all go up to bed, Hermione brings Ursula to her bedroom.

They were looking at some Indian silk shirts, gorgeous and sensual in themselves, their shape, their almost corrupt gorgeousness. And Hermione came near and her bosom writhed, and Ursula was for a moment blank with panic. . . . And Ursula picked up a shirt of rich red and blue silk, made for a young princess of fourteen, and was crying mechanically: ‘Isn’t it wonderful—who would dare to put those two strong colors together—’ (pages 93–94)

1910s fashion timeline (via Glamour Daze archive)

1910s fashion timeline (via Glamour Daze archive)

In the chapter entitled “Rabbit” (chapter 18), Gudrun is hired to teach art to Gerald’s young sister Winifred at his family home of Shortlands. Gerald waits in the garden to catch sight of Gudrun. Gerald is described as “dressed in black, his clothes sat well on his well-nourished body.”

Gudrun came up quickly, unseen. She was dressed in blue with woollen yellow stockings, like the Bluecoat boys. He glanced up in surprise. Her stockings always disconcerted him, the pale yellow stockings and the heavy heavy black shoes. . . . The child wore a dress of black-and-white stripes. Her hair was rather short, cut round and hanging level on her neck.

As she and the child move away to see the child’s rabbit, Bismarck, “Gerald watched them go, looking all the while at the soft, full, still body of Gudrun in its silky cashmere.” He is in love with her, but he is also annoyed “that Gudrun came dressed in startling colors, like a macaw, when the family was in mourning. . . . Yet it pleased him.”

He contrasts her with Winifred’s French governess’s “neat brittle finality of form.” “She was like some elegant beetle with thin ankles perched on her high heels, her glossy black dress perfectly correct, her dark hair done high and admirably.” (pages 245–247)

In Chapter 28, “In The Pompadour,” it is Christmas time, and Rupert and Ursula are now married, and the two couples are travelling to the continent. Gudrun and Gerald travel via London and Paris to Innsbruck, where they will meet Ursula and Rupert. Gudrun and Gerald go to the Pompadour Café after seeing a show at a music-hall. (page 397)

Pussum approached their table: “She was wearing a curious dress of dark silk splashed and splattered with different colors, a curious motley effect.”

As Gudrun flees the café, the far end of the place begins to boo “after Gudrun’s retreating form”:

She was fashionably dressed in blackish-green and silver, her hat was a brilliant green, like the sheen on an insect, but the brim was a soft dark green, a falling edge with fine silver, her coat was dark green, brilliantly glossy, with a high collar of grey fur, and great fur cuffs, the edge of her dress showed silver and black velvet, her stockings and shoes were silver grey. . . . Gudrun entered the taxi, with the deliberate cold movement of a woman who is well-dressed and contemptuous in her soul. (page 401)

Women in Love was written during the first World War and its characters reflect some of the bitterness of that time. Nonetheless, the women’s strength is portrayed in their choice of clothing. Their artistic and intellectual nature is expressed in their elaborate and individual choices of dress.

Another development in Lawrence’s work is his depiction of women in men’s roles and in male clothing. The collection of stories in England, My England take us close to the changing social status of working class women who take on men’s jobs and their clothing and male attitudes.

In “Tickets, Please,” girls work on a single line tramway in the Midlands during war time. The countryside is black and industrial. The drivers are men unfit for active service, cripples and hunchbacks. It is “the most dangerous tram service in England,” as the authorities declare with pride, “entirely conducted by girls and driven by rash young men, a little crippled, or delicate young men who creep forward in terror.”

The trams are “packed with howling colliers.” “The girls are fearless young hussies”: “In their ugly blue uniform, skirts up to their knees, shapeless old peaked caps on their heads, they have all the sang-froid of an old non-commissioned officer.” “They fear nobody—everybody fears them.”

“Tickets, Please” illustration from Strand Magazine, 1919

“Tickets, Please” illustration from Strand Magazine, 1919

The female protagonist in “Tickets, Please” is Annie. She incites the other girls to beat up on one of the male inspectors, John Thomas, who has dated each of them. They are depicted by Lawrence as furious Maenads. Annie takes off her belt and hits John Thomas on the head with the buckle end. They tear off his clothes, kneel on him, beat him, forcing him to choose one of them.

In “Monkey Nuts,” two soldiers are loading hay. The older one, about age 40, is Albert, a corporal, the younger Joe, about 23. They are not in Flanders so life seems good. Into their activities, driving a wagon pulled by splendid horses, comes a land girl, Miss Stokes. “She was a buxom girl, young, in linen overalls and gaiters. Her face was ruddy, she had large blue eyes.”

Land girls, 1915-1918 (courtesy Cambridgeshire Community Archive Network)

Land girls, 1915-1918 (courtesy Cambridgeshire Community Archive Network)

The men begin to flirt with her, and she is attracted to Joe. She begins to make advances, to insist he meet her. The most memorable scene is where she arranges to meet Joe and has changed out of her men’s clothing. Now she is wearing “a wide hat of grey straw, and a loose, swinging dress of nigger-grey velvet.” This is when Albert is able to defeat her, when she is clothed as a woman. Joe doesn’t want her and she doesn’t want Albert, but Albert appears in Joe’s stead.

There is a suggestion of a homoerotic relationship between the two men, but it is not developed. Lawrence intimates that men are becoming less male and women are becoming masculine. War is a disorder in many ways. Once Albert humiliates Miss Stokes, they jeer at her, and begin to call her Monkey Nuts.

The trope of the female in male clothing continues into the novella The Fox (1918), which went through several revisions, until its final form in 1923. A young soldier Henry Grenfel, who has been living in Canada, returns to his grandfather’s farm and finds two women, Nellie March, and Jill Banford living there, running the farm inefficiently. The women call one another by their last names, in masculine fashion. March dresses as a man, a tightly buttoned workman’s tunic, a land girl’s uniform, and she does the heavy work. Banford wears soft blouses and chiffon dresses. Henry decides he will have March and he comes into the women’s relationship like a fox into the hen house. One day he enters the house and March is wearing

a dress of dull, green silk crape. Her dress was a perfectly simple slip of bluey-green crape, with a line of gold stitching round the top and round the sleeves . . . She had on black silk stockings and small, patent shoes with little gold buckles. (pages 48–49)

Seeing her always with

hard-cloth breeches, wide on the hips, buttoned on the knee, strong as armour, and in the brown puttees and thick boots it has never occurred to him that she has a woman’s legs and feet. Now it came upon him. She had a woman’s soft, skirted legs, and she was accessible.

The story has a dramatic and tragic end, but the fox does get his hen in the end.

x

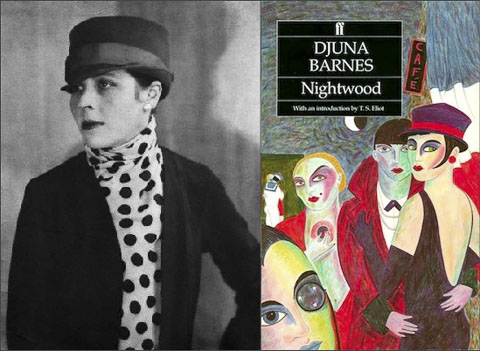

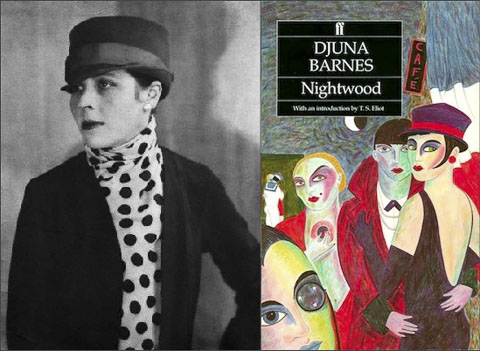

Djuna Barnes (1892–1982)

After studying at the Pratt Institute and the Art Students League, Djuna Barnes lived from 1913 in Greenwich Village, New York, and worked for several newspapers and magazines, including Vanity Fair and The Morning Telegraph, as a journalist, illustrator, and short story writer. Poetry and plays were also published over the next fifteen years, but most of her time in the 1920s was spent in Paris where she was part of a vibrant circle of expats, including James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. She moved to London in 1931, but then returned to America in 1941, and died in New York. Today Barnes is best known for her novel Nightwood, which was first published in England in 1936 with the strong support of T.S. Eliot at Faber & Faber.

Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes

Nightwood defies the conventions of the realistic novel; its characters are all deracinated; its settings of Berlin, Vienna and Paris, and somewhere in the country in New York state, provide mise en scène for highly charged emotional encounters, presented in dense poetic language, a language so metaphorical it creates in its readers a narcotic effect. The reader moves in a vivid haze, part dreamscape, part interior landscape. One’s memory of the book is not confirmed by rereading, but what remains resonates and grows in the mind.

In addition to the vital carnivalesque role of a group of circus performers, there are six characters in the book. The guide to its world, the Virgil in this Purgatoria and Inferno, is an American named Dr. Matthew O’Connor, an impoverished transvestite whose medical bona fides are suspect; yet he is in some way a doctor of the soul, and Nora Flood seeks him out for healing.

The character who is the focus for the action of the text is a young American woman of twenty, Robin Vote. She is the lover of Nora Flood, who is twenty-nine, and of Jenny Petherbridge, a wealthy American divorcee whose four husbands have made her exceedingly rich. Robin has myriad lovers, but she is eternally questing for herself in the night and in the arms of someone new. She is described as a boy in a woman’s body.

The book opens not in the Paris of the 1920s, but in another place and time with the birth of Baron Felix in 1880. We discover him as a man obsessed with the past and with validation through the past. He wears spats and cutaway jackets and clings to the pageantry of kings and queens. In a moment we are in Paris, forty years later, where Felix meets Robin, marries Robin and brings her back to Austria where she gives birth to a child Guido and then deserts the Baron and her newborn child.

It is Robin whose appearance, whose boyish body and clothing, suggest the alterity of this night world of outcasts. We see her first in the Hôtel Récamier, where Dr. Matthew O’Connor, accompanied by Baron Felix, is summoned to attend a young woman who is not well: she lay

heavy and disheveled. Her legs in white flannel trousers were spread as in a dance, the thick lacquered pumps looking too lively for the arrested step, her hands long and beautiful lay on either side of her face. . . . Her flesh was the texture of plant life. . . . About her head there was an effulgence of a phosphorus glowing about the circumference of a body of water . . . the troubling structure of the born somnabule, who lives in two worlds—meet of child and desperado.

Like a painting by the douanier Rousseau, she seemed to lie in a jungle trapped in a drawing room.

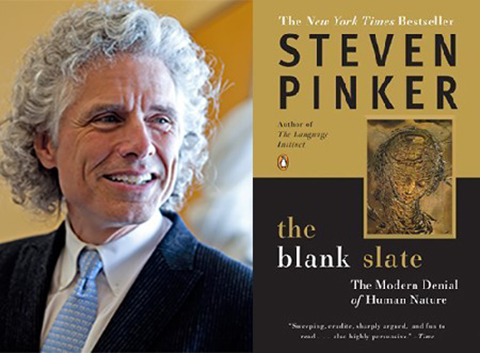

If Robin with her shocking blue eyes appears like a wild beast, her first appearance also conjures a history of painting, in the portraits of Madame Récamier, which were still scattered through this hotel at 3 Place Saint-Sulpice in 1990 when I stayed there, and might still be there to this day. Récamier was famously painted by Jacques-Louis David (1800) and by le Baron Gerard (1805), while posing barefoot, on a chaise longue, in a soft white chiffon dress, enhanced under the bosom with a simple ribbon, her hair in a soft chignon.

Portrait of Madame Récamier by Jacques-Louis David, 1800

Portrait of Madame Récamier by Jacques-Louis David, 1800

The author wearing a summer dress, Montreal 1968

The author wearing a summer dress, Montreal 1968

Robin’s appearance evokes this and confutes it, since she is wearing white flannel trousers and thick lacquered dancing pumps. If Madame Récamier’s bare feet, and her wearing of an undergarment as outer garment, the light muslin slip dress, symbolized the end of the ancient regime and an elevation of nature, Robin’s appearance does the opposite. She is transgendered and encased, and yet she is a danger to all. “The woman who presents herself to the spectator as a ‘picture’ forever arranged is, for the contemplative mind, the chiefest danger.” (page 41)

The Baron’s fascination with Robin comes in part from her appearance:

Her clothes were of a period that he could not quite place. She wore feathers of the kind his mother had worn, flattened sharply to the face. Her skirts were moulded to her hips and fell downward and out, wider and longer than those of other women, heavy silks that made her seem newly ancient. One day he learned the secret. Pricing a small tapestry in an antique shop facing the Seine, he saw Robin reflected in a door mirror of a back room, dressed in a heavy brocaded gown which time had stained in places, in others split, yet which was so voluminous that there were yards enough to refashion. (page 46)

Robin is both a modern girl and an ancient being. Her wearing of vintage clothing is transformative, as she crosses sexual, historical and vestimentary lines. Applying Kaja Silverman’s phrases from “Fragments of a Fashionable Discourse,” we can see how Robin’s recycling of fashion waste denaturalizes her own specular identity.

Other characters also participate in this crossing of genders and epochs, even in dreams. Nora Flood’s grandmother will appear to her in fantasy as a cross-dresser, leering and plump, but also echoing the world of children’s fables like Little Red Riding Hood (pages 68–69), with the Wolf as Grandmother in her nightgown in bed. The doctor is also seen (page 85) in makeup and a woman’s flannel nightgown.

Love of the invert, we are told (page 145), is a search for one idealized gender in another, the girl lost is the Prince found, the pretty lad is a girl. And even one life form in another: Robin “a wild thing caught in a woman’s skin” (page 155), “the third sex” (page 157).

In the final scene (pages 178-179) at a “contrived altar,” “Standing before them in her boy’s trousers was Robin,” and she slides down and begins to bark and crawl after the howling biting dog.

x

Jean Rhys (1890–1979)

I was spending a lot of time in England in the early 1970s, while I worked on my dissertation on William Blake’s paintings, and it was there I discovered the novels of Jean Rhys, shortly after the publication of her novel Wide Sargasso Sea. Looking back I have often wondered whether some of my own feelings about clothing and security, about fitting in, and being both invisible and visible, didn’t come directly from Rhys’s heroines, especially from Julia Martin in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie.

Jean Rhys

Jean Rhys

Did my own desire for a mink coat come from my reading of Rhys’s novels, or from looking at many Blackglama mink ads in the American edition of Vogue magazine, featuring beautiful young actresses and singers at the height of their physical power?

I remember my mother asking my father to buy her a black mink coat for Christmas one year, which he did, of course. And my own acquisition of a mink coat was purchased with my share of our sale of my mother’s house after her death. I remember carrying my dog Lucy up the escalator to the Holt Renfrew fur department on Bloor Street one early winter day. I had decided that if my dog was unhappy among all those dead animals, then I would abandon my plan for a mink coat. Lucy was fine, and I purchased a Gianfranco Ferre mink coat; the Italians were still dominating the fashion runways in the 1990s. My glorious mink coat now sits abandoned in the closet in my guest room, but whether this putting aside bespeaks a new sense of security on my part or simply a shift in fashion trends it would be hard to say.

As a model and an actress Rhys was attuned to the zeitgeist. Women’s confidence and acceptability was embodied in their dress. And she knew about poverty and issues of race firsthand. The BBC documentary on Rhys’s work revealed that while she had been forgotten, like many artists, she was indeed still alive, living in poverty, in the west of England. Educated in Dominica and England, after a brief stint at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, Rhys worked as a chorus girl, was a nude model, and lived as a mistress of a wealthy stockbroker. Eventually, she had three marriages and two children, a son who died young and a daughter. Although she had lived in London, Paris and Vienna, she died in Devon, England. Her trajectory is in many ways akin to that of Canadian author Elizabeth Smart.

Rhys’s work, written in a spare, clear style, focuses on and takes the perspective of rootless, mistreated women, who are frequently down and out in London and Paris. With her BBC-inspired rediscovery, Rhys published Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) where she rewrites Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, from the point of view of Mr. Rochester’s mad wife imprisoned in his attic. Set on a small Caribbean Island, Rhys’s book addresses the European man’s fear of and attraction to a Caribbean woman’s sensuality. Locking up the woman, rejecting and humiliating her, reaffirms his power and puts to rest his fear and repulsion of his own desires.

Rhys’s ongoing concern was the political inequality of women, their powerlessness in a man’s world: “The life of a woman is very different than the life of a man,” observes Julia Martin in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie (1930). It is clothing which confers power and prestige, clothing which is transformative.

At the age of 36, Julia Martin returns to London in search of money, and perhaps love, and also a home, after she has been left in Paris by her lover Mr. Mackenzie. She is careful in her clothing, hoping to make a good impression on her family and she buys a second-hand coat, regretting the sale of her fur coat which would have conferred not only warmth but status.

Julia waited for her uncle

in a large, lofty room crowded with fat, chintz-covered arm-chairs . . . .She was cold, and held her coat together at the throat. The coat looked all right, but it was much too thin. She had hesitated about buying it for that reason, but the woman in the second-hand shop had talked her over.

She thought: “Of all the idiotic things I ever did, the most idiotic was selling my fur coat.” She began bitterly to remember the coat she had once possessed. The sort that lasts forever, astrakhan, with a huge skunk collar. She had sold it at the time of her duel with Maître Legros.

She told herself if only she had had the sense to keep a few things, this return need not have been quite so ignominious, quite so desolate. People thought twice before they were rude to anybody wearing a good fur coat; it was protective coloring, as it were. (page 57)

Julia visits her sister in Acton who lives with their mother and a nurse called Wyatt. Wyatt’s clothing, her wearing a tie, her use of her last name, and her hair cut, plus the severity of her dress suggest she is the lover of Julia’s sister:

The door on the second floor was opened by a middle-aged woman. Her brown hair was cut very short, drawn away from a high, narrow forehead, and brushed to lie close to her very small skull. Her nose was thin and arched. She had small, pale-brown eyes and a determined expression. She wore a coat and skirt of flannel, a shirt blouse, and a tie. (page 68)

Julia is in London for ten days. When she returns to Paris, she is expecting a lover from London named Mr. Horsfield. When he doesn’t turn up, he sends her 10 pounds. Walking along the Seine, Julia imagines

Happiness. A course of a face massage. . . . She began to imagine herself in a new black dress and a little black hat with a veil that just shadowed her eyes.

In her mind she was repeating over and over again like a charm: ‘I’ll have a black dress and hat and very dark grey stockings.’

Then she thought: ‘I’ll get a pair of new shoes from that place in Avenue de l’Opera. The last ones I got there brought me luck. I’ll spend the whole lot I had this morning.’ . . . A ring with a green stone for the forefinger of her right hand.

She spends the whole afternoon in the Galleries Lafayette choosing a dress and a hat. Then she goes “back to her hotel, dressed herself in her new clothes, and walked up and down in her room, smoking.”

In Rhys’s work, the themes of suitable clothes, respectable clothes, and of the little black dress, recur over and over.

The little black dress as a fashion accessory emerges in the 1920s as an essential element of a woman’s wardrobe, with the designs of Coco Chanel and others. Simple, elegant and affordable, it can be dressed up or down with accessories. Before the 1920s, black was the color of mourning, and its stages allowed black and grey. Tints of purple were also popular.

Throughout the twentieth century the charge on the LBD ( Little Black Dress) changed. All of Rhys’s female characters identify the black dress as a powerful and sophisticated symbol of success. It is simple in cut and fabric. In many ways it is classless.

My own clothes closet is brimming with black clothing. This is both symptomatic of an urbanite in Western culture in the later twentieth, and twenty-first century, and also a testament to Coco Chanel’s liberation of women. Here is a portrait of my mother from the 1940s in an iconic LBD. Notice her simple accessory, a necklace with multiple strands of pearls.

Author and father with mother in little black dress and pearls

Author and father with mother in little black dress and pearls

In Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight (1939), Sasha Jansen in her forties comes back to Paris, a place where she once found love and then disaster. She gets a job in a fashionable dress shop as a receptionist. The shop has a branch in London and is owned by an Englishman. He comes over every three months or so, and she is told “he’s the real English type . . . Bowler-hat, majestic trousers, oh-my-God expression, ha-ha eyes—I know him at once.” (page 19)

An old English woman and her daughter come into the shop. The old woman wants to see hair accessories. When she removes her hat, she is completely bald on top.

She tried on a hair-band, a Spanish comb, a flower. A green feather waves over her bald head. She is calm and completely unconcerned. She was like a Roman emperor in that last thing she tried on. (page 22)

Her daughter condemns her mother and says she has made a perfect fool of herself as usual. But Sasha feels the old lady is undaunted.

Oh, but why not buy her a wig, several decent dresses, as much champagne as she can drink, all the things she likes to eat and oughtn’t to, a gigolo if she wants one? One last flare-up, and she’ll be dead in six months at the outside. (page 23)

Sasha rushes

into a fitting- room. . . . I shut the door . . . I cry for a long time—for myself, for the old woman with the bald head, for all the sadness of this damned world, for all the fools and all the defeated. . . .

In this fitting room there is a dress in one of the cupboards which has been worn by a lot of the mannequins and is going to be sold off for four hundred francs. The saleswoman has promised to keep it for me. I have tried it on; I have seen myself in it. It is a black dress with wide sleeves embroidered in vivid colors—red, green, blue, purple. It is my dress. If I had been wearing it I should never have stammered or been stupid. (page 28)

Like her clothing, which is acceptable or not, empowering or not, Sasha says there are locations which are accepting and those which are not:

My life, which seems so simple and monotonous, is really a complicated affair of cafes where they like me and cafes where they don’t, streets that are friendly and streets that aren’t, rooms where I might be happy, rooms where I never shall be, looking-glasses I look nice in, looking-glasses I don’t, dresses that will be lucky, dresses that won’t, and so on. (page 47)

Sasha is picked up by two Russians; “one is impressed by my fur coat.” It is all about appearance. A prosperous appearance gives a woman the strength to go on. Aging is hell, because youth is the key to attractiveness, and attractiveness means men will give a woman money. Hence greying hair must be dyed:

Again I lie awake, trying to resist a great wish to go to a hairdresser in the morning to have my hair dyed. (page 48 )

I must go and buy a hat this afternoon, I think, and tomorrow a dress. I must get on with the transformation act. But there I sit, watching the same procession of shabby women wheeling prams, of men tightly buttoned up into black overcoats. (page 63)

Fashionable fur coats, c.1927

Fashionable fur coats, c.1927

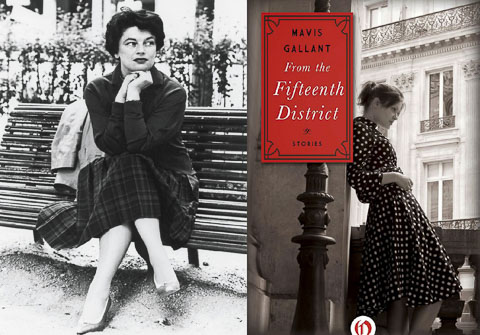

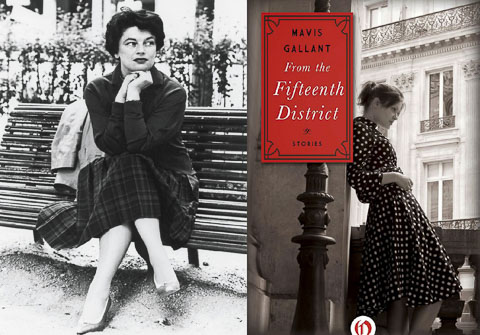

Mavis Gallant (1922–2014)

I met Mavis Gallant in the late 1980s and her conversation through the hours we spent together was of a piece with her depictions of women’s roles, and oppressions, in her fiction. My account of my time with Gallant was published in Numéro Cinq Magazine in September 2014.

Gallant’s From The Fifteenth District (1978) is a series of stories set during and after the Second World War. Their primary focus is a community of expats. Many of the scenes unfold on the border between France and Italy. In the first story, “The Four Seasons,” we find a young Italian servant girl named Carmela, her employer, a parsimonious English woman, Mrs. Unwin, and, next door to them, a Marchesa.

Mavis Gallant

Mavis Gallant

Gallant presents the contrast between these characters in her description of their dress. Carmela wears

A limp black cardigan. . . . She did not own stockings, shoes, a change of underwear, a dressing gown, or a coat,. . . . Carmela’s father was dead, perhaps. The black and the grey she wore, speculates the narrator, were half-mourning. (page 5)

As the time is just before the Second World War, there is an ongoing feud between two neighbours, the Unwins, who are Mussolini sympathizers, and their next door neighbour, the Italian Marchesa. This feud is encapsulated in the narrator’s description of Mrs. Unwin’s smock and her cigarette-stained and freckled hands, in contrast to Mrs. Unwin’s description of the Marchesa’s clothing:

Mrs. Unwin suddenly said she had no time to stroll out in pink chiffon wearing a floppy hat and carrying a sprinkling can; no time to hire jazz bands for parties or send shuttlecocks flying over the hedge and then a servant to retrieve them; less time still to have a chauffeur as a lover. Carmela could not get the drift of this. She felt accused. (pages 4–5)

Although the entire collection of stories is sensitive to the nuances of clothing, my own favourite is perhaps “The Moslem Wife” which uses a single item of clothing, a shawl, as metaphor for a wife’s apparently submissive role.

Shawls have often been associated with elderly women, with aging, and with the cold the aged feel. In Gallant’s story, the heroine Netta is young, but has begun to wear her mother’s shawl as she works with a modern adding machine at the books for her hotel. I myself began to collect shawls in the 1960s, but I have no idea how my own preoccupation came about. I still own my first shawl purchase, a purple silk Indian shawl trimmed in silver.

Here is a picture of me wrapped in this purple silk shawl but wearing a long black linen dress by Canadian designer Brian Bailey. The photograph was taken in the late 1990s.

The author in purple silk shawl, late 1990s

The author in purple silk shawl, late 1990s

My mother did not wear shawls, except occasionally as part of a specific outfit, nor did my grandmother own any shawls whatsoever. Over more than forty years my own shawl collection has grown, although I do give some away occasionally. However, I find it painful to let even one go. The shawl is a powerful symbol, and seems not to be connected with any masculine clothing symbols. There is no question in my mind that my own collection represents some important aspect of my identity, but which identity?

In Gallant’s “The Moslem Wife,” the chief characters are a second-generation expat English family who run a hotel which continues during and after the war. Netta is married to her first cousin Jack. One day she overhears an English doctor refer to her, to Netta, as “ the little Moslem wife.” Soon the idle English colony is calling her by that phrase.

Among the hotel guests are three little sisters from India: “They came smiling down the marble staircase, carrying new tennis racquets, wearing blue linen skirts and navy blazers.” Mrs. Blackley “said, loudly, “They’ll have to be in white. . . . They can’t go on the courts except in white. It is a private club. Entirely in white.” (page 59)

Gallant gracefully sketches English racism in this small moment about the colour of appropriate tennis clothes. In the end, the little girls continue to wear their blue clothes, but they stay at the hotel for their tennis lessons, rather than go to the English Lawn Tennis Club. (pages 58–59)

A shawl enters Gallant’s narrative when Jack’s mad and imperious mother comes to live with them: Netta began “wearing her own mother’s shawl, hunched over a new modern adding machine, punching out accounts” (page 60). The shawl is Netta’s protection and comfort, and it is her conduit to a sort of power line. Others however see it as a sign of submission.

After Jack leaves her alone in the hotel, and runs off with another woman to America, abandoning her and the hotel during the war: “The looking glasses still held their blue-and silver-water shadows, but they lost the habit of giving back the moods and gestures of a Moslem wife.” (page 76)

The shawl and Netta’s title as the Moslem wife, competent as she is running the hotel, overseeing the entire operation, are the symbols of her passivity in the face of her husband’s profligate behavior and her subservience to men. However, she later insists to Jack that when the Italians took over the hotel and the Germans left she was no longer the subservient female: “When the Italians were here your mother was their mother, but I was not their Moslem wife.” (page 78)

North American women’s clothing and the image of the New World girl changes dramatically in life and in Gallant’s stories. The story “Potter” is set after the Vietnam War (1975), that is in the later 1970s, in Paris. So Gallant, in this astonishing collection of stories, runs through five decades in the clothing of her characters. Blue jeans, and long shiny hair, have become part of the uniform of the American girl. Piotr, a Polish immigrant in Paris, falls in love with an American girl living off men.

The girls were Danish, German, French, and American. They were students, models, hostesses at trade fairs, hesitant fiancées, restless daughters. Their uniform the year Piotr met Laurie was blue jeans and velvet blazers. They were nothing like the scuffed, frayed girls he saw in the Latin Quarter, so downcast of face, so dejected of hair and hem that he had to be convinced by Marek they were well-fed children of the middle classes and not the rejects of a failing economy. Marek’s girls kept their hair long and glossy, their figures trim.” (page 219)

Laurie Bennett has “blue eyes, fair hair down to her shoulders, and a gap between her upper front teeth.” (page 220) She is refreshingly and casually well-groomed and makes fun of the stuffy Canadians in the form of her own sister-in-law from Toronto who “wears white gloves all the time, cleans ’em with bread crumbs—it’s true.” (page 221)

x

Alice Munro (1931– )

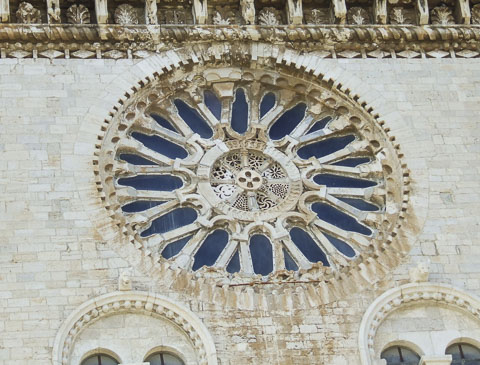

I have never met Alice Munro, although I have seen her onstage and I once wrote a radio program for the Toronto radio station CJRT on her work which is so ironic and nuanced. Like Gallant, Munro is certainly an avatar of my own coming-of-age and costume. You never come to the end of a Munro story. Once while I was lecturing on her work in Italy, I suddenly could hear her regional cadence, which is from my own area of the country, in Canada’s deep south, southwestern Ontario. And yet of course her voice is universal.

Who Do You Think You Are? (1978) consists of ten linked tales which together constitute a bildungsroman of the protagonist Rose. Although eight of the stories were published separately in various magazines, when they were placed together Munro wrote two especially for the collection : “Simon’s Luck” and “Who Do You Think You Are?” In adding these two, she reconstituted the book in the form of an experimental novel.

Alice Munro

Alice Munro

In time span, the stories run from before the Second World War until the early sixties, although time frames are embedded in the details, rather than in specific references to historic events. Rose’s clothes in part mimic her class, and her poverty; she comes from the poor part of town, where the divide between East and West Hanratty is not only a bridge, but also what people eat for breakfast and where their toilet is located. In Rose’s house, the toilet is in the kitchen where farts can be heard as the family eats its meals.

In “Wild Swans,” on her first trip away from home, Rose comes to Toronto by train. As Rose walks through Union Station, she is remembering a friend of her stepmother Flo. Flo’s friend is Mavis who looks like the movie star Frances Farmer and so she “bought herself a big hat that dipped over one eye and a dress made entirely of lace. . . . She had a little cigarette holder that was black and mother-of-pearl. She could have been arrested, Flo said. For the nerve.” (page 69)

Mavis in her clothing mimics the appearance of the film star she resembles and goes to a resort on Georgian Bay in the hopes folks will think she is Francis Farmer herself.

Celebrity clothing, the appearance of film stars, sets one model for women. Glamour and sexuality are what it is really about, the cigarette holder and the lace and the hat dipping over the eye. They are desirable and to be avoided, perhaps even unlawful. Similarly in “The Beggar Maid,” Rose has come to London, Ontario, to university. She has the local dressmaker in Hanratty make her a suit for her new life, but the dressmaker, who is a friend of Flo’s, refuses to make it tight enough. The chapter opens with a glamorous purchase; Rose and her friend Nancy sell their blood for $15 in order to buy fashionable shoes: “They spent most of the money on evening shoes, tarty silver sandals.” (page 70). Later we see Rose wearing the green corduroy suit which was made for her in Hanratty:

The skirt of her green corduroy suit kept falling back between her legs as she walked. The material was limp; she should have spent more and bought the heavier weight. She thought now the jacket was not properly cut either, though it look all right at home. The whole outfit had been made by a dressmaker in Hanratty, a friend of Flo’s whose main concern had been that there should be no revelations of the figure. When Rose asked if the skirt couldn’t be made tighter this woman had said: “You wouldn’t want your b.t.m. to show, now would you?” and Rose hadn’t wanted to say that she didn’t care. (pages 76–77)

Rose gets a job in the college library and a wealthy graduate student named Patrick Blatchford falls in love with her. He compares her to the Beggar in Edward Burne-Jones painting King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid. Class is writ large in the clothing in the painting, the poor beggar girl in a slip and the king in armored clothing. The courtiers looking down on the girl caught within the picture frame.

Patrick says to Rose:

“I’m glad you’re poor. You’re so lovely. You’re like the Beggar Maid.”

“Who?”

“King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid. You know. The painting. Don’t you know the painting?”

Rose studies the painting in an art book. The girl white, “meek and passive,” the King “sharp and swarthy” and “barbaric.” “He could make a puddle of her, with his fierce desire” (pages 81- 82).

In “Mischief,” Rose, now married to Patrick, begins an affair with her best friend Jocelyn’s husband Clifford, a musician. Rose has ambitions to be an actress. Patrick expects her to dress conservatively, but she wants to wear toreador pants (page 111). It is the Beat era, so black is becoming the fashionable colour for artists:

A few of the girls were in slacks. The rest wore stockings, earrings, outfits much like her own. . . . And most of the men were in suits and shirts and ties like Patrick. . . . A few men wore jeans, and turtle necks or sweatshirts. Clifford was one of them, all in black. (pages 112–113)

Rose goes to Powell River to meet Clifford. There is no bus depot and the only place to wait is on the porch of a loggers’ home for old men:

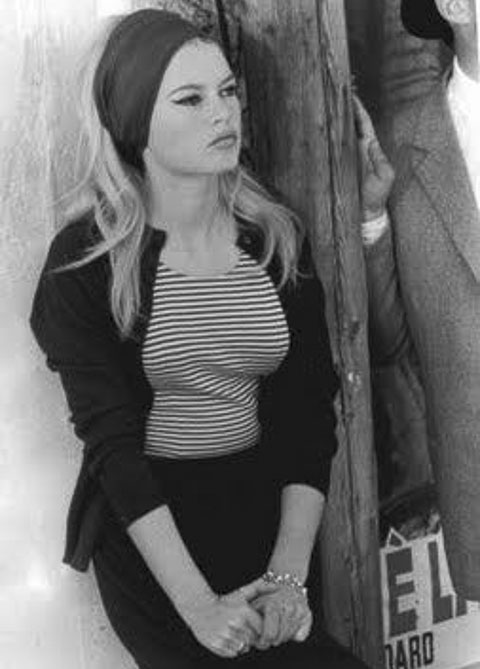

There was no place to loiter. She thought people stared at her, recognizing a stranger. Some men in a car yelled at her. She saw her own reflection in store windows and understood that she looked as if she wanted to be stared at and yelled at. She was wearing black velvet toreador pants, a tight fitting high-necked black sweater and a beige jacket which she slung over her shoulder though there was a chilly wind. She who had once chosen full skirts and soft colors, babyish angora sweaters, scalloped necklines, had now taken to wearing dramatic sexually advertising clothing. The new underwear she had on at this moment was black lace and pink nylon. In the waiting room at the Vancouver airport she had done her eyes with heavy mascara, black eyeliner, and silver eye shadow; her lipstick was almost white. All this was the fashion of those years and so looked less ghastly than it would seem later, although it was alarming enough. (page 127)

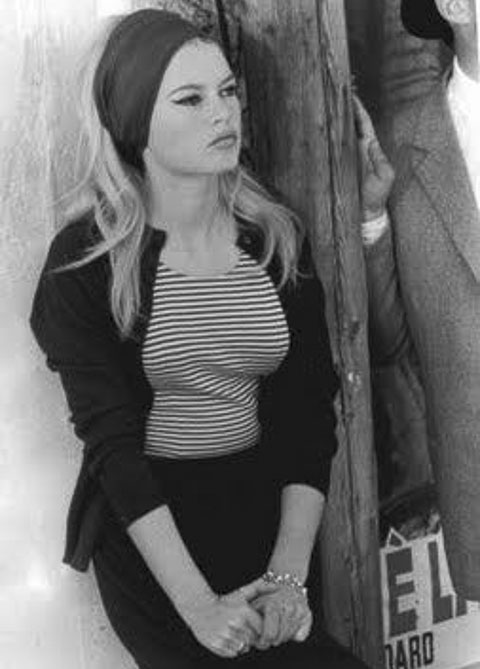

Brigitte Bardot wearing Beat clothing in Le Mépris, 1963

Brigitte Bardot wearing Beat clothing in Le Mépris, 1963

Rose’s clothing, that of the emerging artist and of her own sexual liberation, contrasts dramatically with her friend Jocelyn who wears her husband’s old clothes. But Jocelyn comes from a wealthy family and has nothing to prove.

In “Simon’s Luck,” Rose, who is now a professor at Queen’s University, takes up with a man at a party. The host is wearing a “velvet jumpsuit” (page 167). This was the hippy era, late sixties: “He was looking very brushed and tended, thinner but softened, with his flowing hair and suit of bottle-green velvet.” A costume which resonates with those velvet suits of my brother and my soon-to-be husband at my own wedding in London in this era.

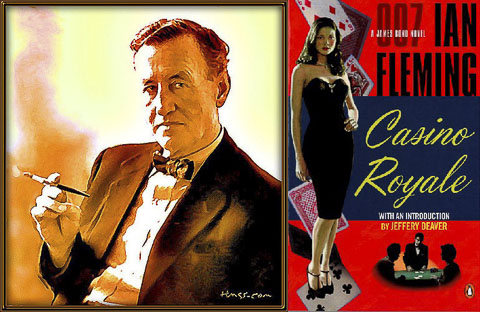

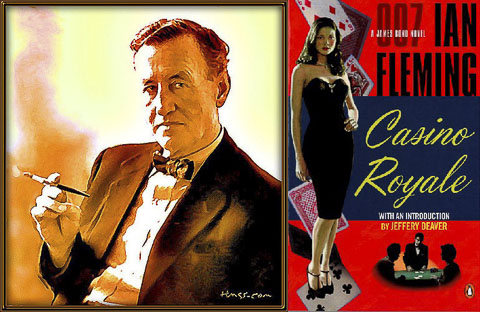

Novelists’ alertness to dress as exemplifying and creating character interacts with questions of commodification and branding. It’s hard to say what exactly branding is. Easy to point to the display of the logos of designers, but something else is surely afoot. Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, which are structured like the tales of Tolkien and the schema of Joseph Campbell, medieval grail knights’ tales, have over time and immense popularity become branding opportunities. These opportunities were certainly set in place by Ian Fleming himself, as a look at Fleming’s texts, even before the James Bond films, demonstrates.

x

Ian Fleming (1908–1964)

Set during “a new era of fashion and prosperity,” Ian Fleming’s bestselling tales of Secret Agent 007, James Bond, have sold more than 100 million copies. There are 14 Bond books—12 novels and two short story collections. Films continue to be made with the central figure, Secret Agent 007, and always with at least one beautiful woman, and lots of technology—flame throwers, guns, cameras, cars, and the like. These books are one bellwether for changes in fashion in literature. Their proliferation of luxury commodities signal the shift in popular media to all sorts to branding.

The first Bond book, Casino Royale (1953), sets the template of branding, of consumer culture, of luxury goods evoked and validated by name, which accelerates through the next half century. The book is set in the Hotel Splendide, and at the Casino Royale-les-Eaux in France, at the mouth of the Somme, in south Picardy. The location is a watering hole, as Fleming describes it, in a “new era of fashion and prosperity.” This is the 1950s, the1930s depression is over, as is the Second World War.

Ian Fleming

Ian Fleming

Everything in Bond’s world is bespoke, specially chosen, specially constructed, and expensive. Bond’s cigarettes are “a Balkan and Turkish mixture made for him by Morlands of Grosvenor street” (page 22). He keeps them in “a flat gunmetal box,” which holds “fifty of the Morland cigarettes with the triple gold band” (page 49). Bond’s French aide smokes Caporals. Bond’s radio, personally delivered by a salesperson from Paris—who is in fact another secret agent—is a Radio Stentor, and his car is a 1933, 4 ½ litre battleship-grey convertible coupe Bentley ( page 30).

In the Hermitage bar, Bond sees men drinking champagne and women dry martinis made with Gordon’s gin (page 31). One man is in a tweed suit with a shooting stick from Hermès.

Bond’s first meeting with his female assistant for this mission, Vesper Lynd, displays her in a

medium-length dress of grey “soie sauvage” with a square-cut bodice, lasciviously tight across her fine breasts. The skirt was closely pleated and flowed down from a narrow, but not a thin, waist. She wore a three-inch, hand-stitched black belt. A hand-stitched black “sabretache” rested on the chair beside her together with a wide cartwheel hat of gold straw, its crown encircled by a thin black velvet ribbon which tied at the back in a short bow. Her shoes were square-toed of plain black leather. (pages 32–33)

Bond meets his CIA counterpart who drinks Haig and Haig scotch (page 43). Bond drinks a dry martini, shaken not stirred, in a deep champagne goblet—“three measures of Gordon’s, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice cold and then add a large slice of lemon peel. Got it?” (pages 43–44) He prefers his vodka made with grain rather than potatoes. His cigarette lighter is a Ronson; his weapon of choice is a .25 Beretta: “a very flat .25 Beretta automatic with a skeleton grip” (page 49). Bond’s clothing is as carefully detailed as his accessories: “single-breasted dinner-jacket, over his heavy silk evening shirt, with a double silk tie” (page 49).

Vesper Lynd’s clothes are from Paris; she has a friend who is a vendeuse and so, in the casino itself, she is wearing a borrowed black velvet Christian Dior dress. Dior had shown his first collection in Paris only in 1947, establishing Paris as a centre of fashion. The choice of Dior demonstrates just how attentive Fleming was to the luxury items of the moment. Later Vesper will say her grey dress was also a borrowed Christian Dior (page 56).

Her dress was of black velvet, simple and yet with the touch of splendor that only a half a dozen couturiers in the world can achieve. There was a thin necklace of diamonds at her throat and a diamond clip in the low vee which just exposed the jutting swell of her breasts. She carried a plain evening bag. . . . Her jet black hair hung straight and simple to the final inward curl below the chin. (page 50)

When Bond has dinner, he is precise in his order. Initially he orders the Taittinger 45 champagne, but he allows the waiter to suggest a Blanc de Blanc Brut of 1943.

“You must forgive me,” he said. “I take a ridiculous pleasure in what I eat and drink. It comes partly from being a bachelor, but mostly from the habit of taking the trouble over details.” (page 53)

Near the end of the narrative, Vesper and Bond are at a family-run seaside inn. They have both changed their style of clothing.

He is

dressed in a white shirt and dark blue slacks. He hoped that she would be dressed as simply and he was pleased when, without knocking, she appeared in the doorway wearing a blue linen shirt which had faded to the color of her eyes and a dark red skirt in pleated cotton. ( page 158)

Dr No (1957), the sixth of the Bond thrillers is set primarily in the Caribbean, in Jamaica and on a small island off shore. The central female, “Honeychile” Rider, appears naked on the beach, like a Girl Friday to Bond’s Robinson Crusoe. An innocent, a sort of noble savage, she is the sole survivor of an old Jamaican family which has lost its money. Her dream is to become a New York call girl. As a child of nature, she is every man’s dream child/lover.

The villain of the text is Dr No, a recluse with a fascination with pain and a pair of pincers for hands. Most of the men on Dr No’s off shore island wear Chinese kimonos. The food in his hideout is perfect, and all the bath accessories are brand names.

Bond went to one of the built-in clothes cupboards and ran the door back. There were half a dozen kimonos, some silk and some linen. He took out a linen one at random. . . .

There was everything in the bathroom—Floris Lime bath essence for men, Guerlain bathcubes for women. He crushed a cube in the water and at once the room smelled like an orchid house. The soap was Guerlain’s Sapoceti, Fleurs des Alpes. In a medicine cupboard behind the mirror over the washbasin were toothbrushes and toothpaste, Steradent toothpicks. Rose mouthwash, dental floss, Aspirin and Milk of Magnesia. There was also an electric razor, Lentheric aftershave lotion, and two nylon hairbrushes and combs. Everything was brand new and untouched. (pages 182–183)

Confronting Dr No, the imprisoned Bond keeps his aplomb and orders “a medium Vodka dry Martini—with a slice of lemon peel. Shaken and not stirred, please. I would prefer Russian or Polish vodka.” (page 203).

The Bond novels are charming, brilliantly constructed adult fairy tales, but like all fairy tales they carry important cultural-political lessons.

x

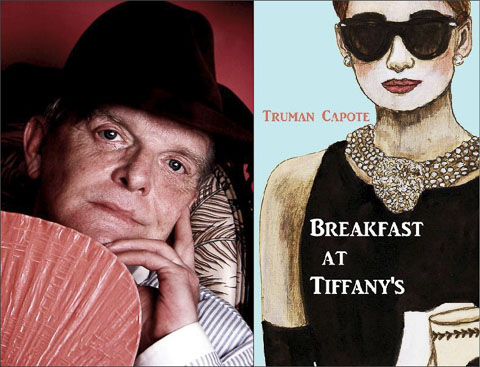

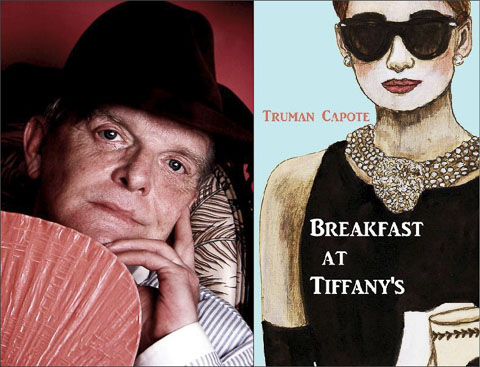

Truman Capote (1924–1984)

For me, and for many of my generation, the 1961 film of Truman Capote’s novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958), starring Audrey Hepburn, captured the era. In retrospect, it seems to me like a summation of the trends found in the earlier fictions from Lawrence to Gallant. While the film is a romantic and memorable adaptation of Capote’s novella, the novella itself is a sophisticated investigation of class and character. And it is a perfect work of art. The prose is exquisite, spare, clean and evocative, and designed to foreground its central figure, Holly Golightly, a nineteen-year-old starlet, on the lam from Hollywood and her older widowed veterinarian husband with his four children, a man whom she had married at the age of fourteen.

Truman Capote by Jack Mitchell (Wikimedia Commons)

Truman Capote by Jack Mitchell (Wikimedia Commons)

Image of Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly courtesy Grace Hamilton

The novella unfolds through retrospective action—a call from a bar and the barkeep Joe Bell leads the narrator to recall his life in an apartment in a brownstone, where Holly Golightly was a tenant in 1943. Joe Bell’s bar on Lexington Avenue was often used by both Holly and the narrator to make telephone calls.

Although Capote’s novel has lived on in popular mythology through the film adaptation, it is in the novel that improvisational identity is tied to clothing. And in Capote’s narrative, it makes perfect sense. Holly, after a stint in Hollywood where she was being groomed for stardom and saw the opportunity as a way to vamp herself, including learning some French, understands that dressing will be the way she rises above street prostitution. Clothing will enable her to present herself as a girl who should be given a handsome amount of money to go to the powder room.

The little black dress becomes Holly’s costume of elegance, refinement and versatility. Throughout, Capote contrasts Holly with the men she hangs out with—youth and age, innocence and experience. The men are cartoons, caricatures, criminals, bounders, chubby in buttressed pin stripe suits, sexually unrealized heirs who yearn for a spanking, skinny rich conventional South American diplomats, Hollywood agents with the money and the power and the big cigar, soldiers in uniform.

Holly wears simple understated clothes, plays old show tunes, rides horses, wears gloves. Although her living quarters are messy, like a teenager’s, she always emerges unscathed. In the opening scene in Joe Bell’s bar, the narrator looks at what Joe Bell has handed him:

In the envelope were three photographs, more or less the same, though taken from different angles: a tall, delicate Negro man wearing a calico skirt and with a shy, yet vain smile, displaying in his hands an odd wood sculpture, an elongated carving of a head, a girl’s, her hair sleek and short as a young man’s, her smooth wood eyes too large and tilted in the tapering face, her mouth wide, overdrawn, not unlike clown-lips. On a glance it resembled most primitive carving; and then it didn’t, for here was the spitting-image of Holly Golightly, at least as much of a likeness as a dark still thing could be. (page 6)

Joe Bell, the bartender who, like the narrator, is in love with her, sees “pieces of her all the time, a flat little bottom, any skinny girl that walks fast and straight . . .” (page 8 )

The narrator had lived in New York in the same brownstone on the upper east side as Holly. He notices on the mailbox, in the name slot for Apt 2, a formal printed card which reads: “Miss Holiday Golightly, Traveling.” Later, he learns she had purchased her card at Tiffany’s, and he also will learn what Tiffany’s represents for Holly.

He first sees Holly late one warm evening:

She was still on the stairs, now she reached the landing, and the ragbag colors of her boy’s hair, tawny streaks, strands of albino-blond and yellow, caught the hall light. It was a warm evening, nearly summer, and she wore a slim cool black dress, black sandals, a pearl choker. For all her chic thinness, she had an almost breakfast-cereal air of health, a soap and lemon cleanness, a rough pink darkening in the cheeks. Her mouth was large, her nose upturned. A pair of dark glasses blotted out her eyes. It was a face beyond childhood, yet this side of belonging to a woman. I thought her anywhere between sixteen and thirty; as it turned out, she was shy two months of her nineteenth birthday.

She was not alone. There was a man following behind her. The way his plump hand clutched at her hip seemed somehow improper, not morally, aesthetically. He was short and vast, sun-lamped and pomaded, a man in a buttressed pin-stripe suit with a red carnation withering in the lapel. . . . his thick lips were nuzzling the nape of her neck. (pages 10–11)

Holly’s clothing presents her as demur and innocent and refined:

She was never without dark glasses, she was always well-groomed, there was a consequential good taste in the plainness of her clothes, the blues and grays and lack of luster that made her, herself, shine so. One might have thought her a photographer’s model, perhaps a young actress, except that it was obvious, judging from her hours, she hadn’t time to be either. (page 12)

One evening on his way home, the narrator noticed a cab-driver crowd gathered in front of P.J. Clarke’s saloon, apparently attracted there by a happy group of whiskey-eyed Australian army officers baritoning “Waltzing Matilda.” As they sang they took turns spin-dancing a girl over the cobbles under the El; and the girl, Miss Golightly, to be sure, floated round in their arms light as a scarf.” (page 13)

Holly smokes “an esoteric cigarette,” charmingly called by Capote, Picayunes; she “survived on melba toast and cottage cheese”; “her vari-colored hair was somewhat self-induced. . . . Also, she had a cat and she played the guitar” and had “white satin pumps.”

He often hears her playing her guitar while she dries her hair sitting on the fire escape.

She played very well, and sometimes sang too. Sang in the hoarse, breaking tones of a boy’s adolescent voice. She knew all the show hits, Cole Porter and Kurt Weill; especially she liked the songs from Oklahoma! which were new that summer and everywhere . . . harsh tender wandering tunes with words that smacked of pineywoods or prairie. (page 14)

She chooses older men, established men, with money: “I can’t get excited by a man until he’s forty-two. I was fourteen when I left home” (page 16). Although all the men around her are unlike one another, none is young. Rutherford “Rusty” Trawler is “a middle- aged child that had never shed its baby fat . . . his face had an unused virginal quality . . . his mouth . . . a spoiled sweet puckering” (pages 28–9).

Holly’s place of peace is Tiffany’s whenever she is down, whenever she gets “the mean reds,” not the blues but worse.

What I’ve found does the most good is just to get into a taxi and go to Tiffany’s. It calms me down right away, the quietness and the proud look of it; nothing very bad could happen to you there, not with those kind men in their nice suits, and that lovely smell of silver and alligator wallets. (Page 32)

Holly’s world is her absent brother Fred, who is a soldier, and the men, including O.J. Berman, who was her agent when she was in training for film, along with her model friend Mag Wildwood and Mag’s South American boyfriend.

He’d been put together with care; his brown head and bull fighter’s figure had an exactness, a perfection, like an apple, an orange, something nature has made just right. Added to this, as decoration, were an English suit, and a brisk cologne and, what is still more unlatin, a bashful manner. ( page 39)

Holly keeps her room like a girl’s gymnasium, but always emerged “from the wreckage pampered, calmly immaculate with her lizard shoes, blouse, and belt.” (page 43)

Audrey Hepburn, screenshot from trailer for Breakfast at Tiffany’s (via Wikimedia Commons)

Audrey Hepburn, screenshot from trailer for Breakfast at Tiffany’s (via Wikimedia Commons)

Holly is a Manhattanite, but she is still rooted in her hillbilly past. She goes riding in Central Park, wearing jeans which were then still farm work clothes, not city wear. When she is arrested for her alleged role in a drug-smuggling racket she is wearing her riding costume, tennis shoes, blue jeans and a windbreaker. In the newspaper, the photograph of her shows her wedged between two muscular detectives, one male, one female:

In this squalid context even her clothes (she was still wearing her riding costume, windbreaker and jeans) suggested a gang-moll hooligan: an impression dark glasses, disarrayed coiffure and a Picayune cigarette dangling from sullen lips did not diminish. (page 71)

Her iconic black dress re-emerges when she goes to the airport, leaving NYC, fleeing her bail on the charges of helping the drug racket of underworld mobster Sally Tomato, to whom she made weekly Thursday visits in Sing Sing prison: “Holly stripped off her clothes, the riding costume she’d never had a chance to substitute, and struggled into a slim black dress.” (page 84)

And in that moment the genius of Coco Chanel, inventor of the LBD, is reconfirmed.

x

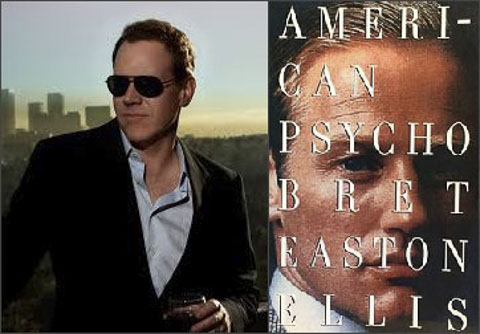

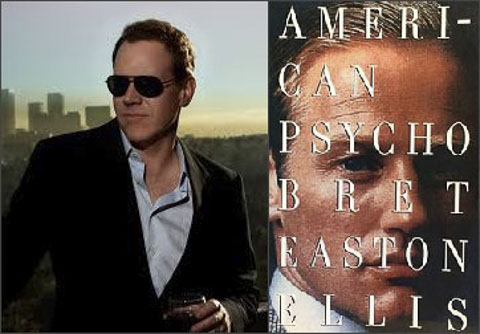

Bret Easton Ellis (1964–)

The literary movement into branding, and not merely into luxury, takes a grotesque turn in Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho (1991). As so often we ask ourselves, are artists the recorders of what is, or the makers of what must be? How to distinguish the permeable membrane?

Bret Easton Ellis

Bret Easton Ellis

In Ellis’s best-known third novel, the central figure is a serial killer, a Manhattan business man called Patrick Bateman. The novel presents itself as a satire on the consumer culture of late twentieth-century America. Of interest is the extreme form of fashion branding, perhaps for satirical purposes. Every single page presents myriad brands to the reader who becomes enveloped in a haze of consumerism. The examples which follow are not unique, but characteristic of each page of Ellis’s text.

I go into the bedroom and take off what I was wearing today: a herringbone wool suit with pleated trousers by Giorgio Correggiari, a cotton oxford shirt by Ralph Lauren, a knit tie from Paul Stuart and suede shoes from Cole Haan. I slip on a pair of sixty-dollar boxer shorts I bought at Barney’s and do some stretching exercises . . . (pages 72–73)