Deforming Forms: Outlier Short Stories and How They Work

By: Richard Farrell

I once spent an entire day at The Art Institute of Chicago, wandering alone for hours through the vast museum. I began in a gallery filled with artifacts from ancient civilizations and moved chronologically through the collection, passing the pharaohs’ coffins from ancient Egypt, the shards of classical Greece, the religious art of late antiquity, the medieval tapestries, and the Renaissance sculptures. I marveled at the massive rooms filled with Impressionist paintings, and eventually ended the day in galleries filled with the strange pieces of ‘modern art’, the often abstract objects, difficult to categorize or comprehend. I never studied art or art history in school—Annapolis tended to ignore the humanities in favor of the art of war—so what I knew of art came mostly from pop culture. I recognized the famous Seurat painting A Sunday on La Grande Jatte because I had seen it in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Though embarrassed by my ignorance, I began to experience a visceral understanding of the progression of styles as I moved through the collection. I became aware that these shifting styles related to one another, that classical forms evolved slowly into more modern, abstract expressions. Standing in front of a Kandinsky painting, with its strange geometric shapes, or a Jackson Pollock painting, with its seemingly chaotic splashes of colors, felt very different than standing in front of a painting by Pissarro. Yet the essence of what I experienced felt connected. I kept asking myself the question: What makes something a work of art?

Modern abstract art had always seemed inaccessible before this experience. I was guilty of appreciating works of art for little more than what Douglas Glover calls “the resemblance they bear to old dead people in funny clothes.” (Notes Home from A Prodigal Son)

Standing in the modern gallery that day in Chicago, I learned that the formal aspects of art accomplish more than recreating a sense of reality. Though I saw connections to historical forms and styles, I had no context for the experience, no intellectual background to support my emotional reaction. This glaring hole in my intellect (one of many) has continued to gnaw at me ever since.

As I’ve begun to study writing more seriously, my interest has focused on the aesthetic principles that make a story or a novel work. And just like in the museum, there is a vast continuum of story-types, stories which refuse to follow traditional models. I’m particularly fascinated by stories which stretch the boundaries of storytelling. Call them experimental, avant-garde, or ‘outliers,’ but some stories refuse to follow long-standing techniques. I should say up front that I enjoy stories in the realist tradition. I enjoy writing that creates a strong sense of verisimilitude and stories that rely on conventional devices. Well-made, conventional stories are the stories I most often read and try to emulate when I write, but I have to admit, I’ve never asked myself why. The premise goes unquestioned. And not questioning convention can lead to bland, unthinking products. By exploring the unconventional, the outlier in short story form, I hope to arrive at a deeper appreciation of story architecture in all its varied forms, conventional and otherwise. I hope the following pages will help re-envision the idea of a story and expand the boundaries about what makes a story.

From the Conventional to the Outlier:

The well-made, conventional short story rests on certain structural foundations, and though there is no strict definition, those foundations typically include point of view, character, plot, setting, and theme. These devices create a recognizable pattern for the conveyance of meaning to the reader. Most stories I read employ these devices rigorously, so much so that when I come across an outlier, the effect is startling. Glover, in Notes Home from a Prodigal Son, talks about these assumptive structures in an essay on a Leonard Cohen novel, Beautiful Losers: (These same conventions hold true for short stories as well as novels.)

“The conventional view of the novel has it developing out of the late Renaissance picaresques. It becomes the literary vehicle of the rising middle class in England and elsewhere, and, in the nineteenth century, the novel becomes, for the capitalist bourgeoisie, what the Gothic cathedral was to an earlier version of Western civilization. The novel expresses, often ironically, the bourgeois ethos with its will to power and its will to love, in short its conflicted and inauthentic soul. But the bourgeois, conventional novel itself, with its emphasis on plot (a unidirectional series of causally related events), character (based on a common-sense theory of self, the individual and personal identity), setting and theme—on verisimilitude, the quality of seeming to be real—challenged the middle class only ever so slightly. The assumptions of the novel—in structure and presentation—remained the assumptions of its primary readers. In other words, the novel is a modern art form and its structure reflects the assumptions of modernity, the individual and bourgeois capitalism.”

Within the conventional story, devices can become so ingrained that they disappear into the background, and a dangerous assumption (one I’ve made) can occur: that these devices, these methods of writing, are mistaken for rules, for ideology instead of methodology. The devices, “the assumptions of the novel” (or story), once expected, go almost unnoticed, “reflecting the assumptions of modernity,” leading to what the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky in Theory of Prose calls “automatization,” the inability to see what is before us.

“The object passes before us, as if it were prepackaged. We know that it exists because of its position in space, but we see only its surface. Gradually, under the influence of this generalizing perception, the object fades away. “

Conventional stories rely on these devices and the reader expects them. And conventional stories remain a predominant form in fiction. As these devices gain ascendancy in the creation of conventional stories, they easily fade from our awareness.

At this point, another dangerous assumption can occur (and again, one I’ve been guilty of making): that these devices, these methods of writing fiction have arisen naturally, that they are inextricably linked to the act of writing fiction itself. Terry Eagleton, in Literary Theory, talks about the dangers of ‘naturalizing’ social realities, which could include things like fictional devices.

“It is one of the functions of ideology to ‘naturalize’ social reality, to make it seem as innocent and unchangeable as Nature itself. Ideology seeks to convert culture into Nature, and the ‘natural’ sign is one of its weapons. Saluting a flag, or agreeing that Western democracy represents the true meaning of the word ‘freedom’ become the most obvious, spontaneous responses in the world. Ideology, in this sense, is a kind of contemporary mythology, a realm which has purged itself of ambiguity and alternative reality.”

Now I do not suggest that there is a sinister conspiracy behind conventional fiction. I don’t think that the progression from assumptive forms of story construction will lead us to the lockstep mentality of fascism in writing. But if Harry Potter is a commercial literary phenomenon, the merits of which are highly debatable, it is also a phenomenon that has created a cottage industry of wizardry and magic books around it. The marketplace demands uniformity, and repetition is the model. It craves methods that go unnoticed, unquestioned and unchallenged. Like medieval bishops selling indulgences to raise money for grander and grander cathedrals while the peasants starve, the contemporary publishing industry sells its brand of indulgences in the form of homogenized books, driven by a relentless march toward the bottom line, the capitalist equivalent of Judgment Day.

One function of art must be to resist this automatization and present alternatives to the expected, to fight assumptions and to force the reader to see freshly, leading to what Shklovsky calls a “vision” of the object, rather than a “recognition.” Shklovsky again:

“And so, in order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to a knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition. By “estranging” objects and complicating form, the device of art makes perception long and laborious. The perceptual process in art has a purpose all its own and ought to be extended to the fullest. Art is a means of experiencing the process of creativity. The artifact itself is quite unimportant.”

This leads me to the topic of outliers, to stories which might be called experimental or unconventional, where some estrangement of the expected form is at work. In these stories, the conventional devices of plot, character, setting, point of view and theme are altered, often radically. Yet these stories still function and meet the expectations of a story, as opposed to a poem or an essay. In outlier stories, the goal remains to create what Leon Surmelian calls “a coherent account of a significant emotional experience, or a series of related experiences organized into a perfect whole,” but with the conventional forms ‘deformed’ into something that challenges the reader’s understanding of a story. It requires labor and effort to apprehend. The outlier story asks the reader to read as if for the first time, as if discovering something entirely new.

Glover, In Notes Home From a Prodigal Son, refers to this deformation of structural devices in his essay on the Canadian writer Hubert Aquin:

The primary devices of the well-made novel—plot, character, setting and theme—are designed to imitate the structures of this so-called reality. They situate and reassure the reader by promoting verisimilitude, the quality (or illusion) of appearing real. By emphasizing the difficulty, or even impossibility, of producing meaning over meaning itself, by piling up alternative but equivalent semiological systems, Aquin obliterates these conventional novelistic devices.

Notes Home from a Prodigal Son

The outlier story piles up alternative but equivalent systems to replace the absent devices. It works against convention, like the construction of a different type of cathedral, using different blueprints, different materials, but with the ultimate goal still the same. The risk, of course, is that such variance can lead to unstable, unsatisfying, or incomplete stories, a cathedral which collapses under the weight of its own design. The alternative methods risk making the story so abstracted that it becomes unreadable. Glover addresses this too:

For Aquin, difficulty resides in substituting the proliferating unsystematic, non-structures of “institutional delirium” for the conventional structures of the well-made novel. But this does not mean his novels are insane, nonsensical, unstructured or impossible to read. The phrase “institutional delirium” is itself a trope, a metaphor for the kind of structure Aquin uses to oppose the structures of the conventional, well-made novel. His novels only appear to be unstructured so long as we apply to them the same criteria for structure as we apply to the well-made novel. In fact, Aquin’s novels do have plots, characters, settings and themes; it’s just that when Aquin uses a conventional novelistic device, he deliberately and relentlessly deforms it in order to prove that he doesn’t need it. In the jargon of the Russian Formalists, Aquin makes things strange.

By estranging the conventional device, by bringing attention to it, or by directing attention away from it, the writer creates an equivalent structure that reinvigorates the reader’s awareness of form. By de-emphasizing conventional devices, by eliminating characters, narrators, settings, conventional plots, the reader is challenged to discover new criteria for the judgment of art and to reexamine the very idea of a story. If done well, I would argue, the outcomes of the well-made conventional story and the well-made outlier story are the same: the “perfect whole.”

In the following stories, each author has manipulated conventional devices and attempted to create an alternative version of a story. With varying degrees of estrangement, playfulness, cleverness and success, each of the following stories reorients the reader’s expectation. Yet outliers do not indict the conventional story. They are oppositional, but also complementary. They force the reader to acknowledge form as different, and hopefully to consider the purpose behind form. Glover puts it this way in The Enamoured Knight:

What seems to be the case with experimental fiction is that it is always written with other, more conventional books or conventional notions of reality in mind; one of the primary effects of experimental works is the denial of expectation, the surprise the reader feels when form is inverted or twists back on itself or is in some other way subverted. Most commonly the experimental artist does this simply by drawing attention to the work of art as a work of art. A painting isn’t about the image it represents; it’s about surface, shape and colour. A book is a book. In this way, oddly enough, the experimental novel is tied to the strict realist novel, the same but opposite, like the right and left hand. They are both committed to a species of honesty, authenticity, or “realism.” But the larger novel tradition swears allegiance to verisimilitude while the experimental tradition diminishes the importance of illusion and highlights the reality of the work itself, its materials, tools and process. The goalposts, as I say, have been moved.

Rather than goalposts, I’ll return to the religious metaphor: the pilgrim is asked to look beyond the walls of the Gothic cathedral, past the rituals of the mass, and into the realm of a different church, one that reminds him of the reason for all this prayer and devotion: not the building, but of the great mystery of being which the story tries to understand. It’s the reason for all the bricks and mortar in the first place.

“In the Fifties” by Leonard Michaels

Leonard Michaels’ six page, first-person short story “In the Fifties” uses an unnamed narrator to recount a list of events that happened during the eponymous decade. The story is told as a fragmented series of episodes from the narrator’s life, not unlike the structure of a list. No apparent chronological order exists in recounting this list beyond a loose geographical orientation (he mentions New York, Michigan, Massachusetts, and California as places he lived) plus the assumptive time period of ten years. Certain patterns repeat throughout the story: women, sex, roommates, an anti-establishment sensibility, language, academics, violence and suicide. At four points in the retrospective story, the narrator establishes a present narrative time period with the word ‘now’ or with a present tense verb construction, so that the reader knows the story is being told reflectively.

The story opens with the narrator learning to drive a car, studying, attending college, reading, having personal relationships, meeting card sharks and con men, and interacting with women. When a respected teacher is fired at NYU, the narrator expects an uprising that does not happen. He moves to Massachusetts and works in a fish-packing plant where he notices old Portuguese men cleaning the fish. He falls in love (though it is unrequited), becomes an uninspired teaching assistant, is arrested, does drugs, witnesses an abortion and drives a car recklessly through the fog. After this, the first named character, Julian, appears. Julian and the narrator spend a period of time as friends. Then the list resumes, and the narrator remembers playing basketball and shooting a gun. He then lives with a roommate who ‘suffers’ from life and eventually kills himself. The narrator then works as a waiter in the Catskills, lives the life of a hipster in Greenwich Village, and moves to California. After this, the second named character enters, a man named Chicky, who burns his face and wants to kill himself because his girlfriend is ugly. The story concludes with the narrator going to a demonstration in support of a friend who has been arrested. He witnesses a large crowd gathering to protest this injustice (the friend has been arrested for wanting to attend the HUAC hearings) and he hears a mother telling her little kid not to unleash a bag of marbles under the police horses. Within the chronicled ten years, the narrator experiences a range of events, including rigorous study, teaching, passion, despair, death, disillusionment, and maturity.

This story posits a number of difficulties for the reader expecting a traditional, realist story. The first challenge I’ll examine will be Michaels’ unconventional method of character development. The pattern in a conventional story typically involves two (or more) characters thrown into repeated conflicts, the progression of which gradually reveals more about each character. Michaels turns this convention around, primarily through an ironic foregrounding and backgrounding of characters.

While the first-person narrator’s presence dominates the pages, other characters exist mostly as un-named figures who weave in and out of the narrator’s awareness. Only two fictional characters are actually given names, Julian and Chicky, though twenty historical figures are mentioned by name. (A third character, Leo, is mentioned by name by never appears in dramatic action.) While this story involves a large cast of characters, most remain in the background because the narrator refuses to name them. They are called variously, “my roommate,” “a fat man,” “a man,” “two girls,” “a sincere Jewish poet,” “three lesbians,” “a friend,” and “a girl from Indiana.” Even though the narrator says “Personal relationships were more important to me than anything else,” very little about most of the characters in the story appears personal. Is there anything less personal than refusing to name a character?

Even the narrator remains elusive. We learn about events that happened to him, not how those events affected him. We do not know where he is now, how he views these events, nor how these events have shaped his character. Though present significantly on the page in the form of the pronoun, “I,” he remains hard to define. Curiously, he is more easily understood by his absence than by his presence.

About halfway through the story, a shift occurs. One character is given a name, another character is foregrounded, and the narrator begins to recede. This is first noticeable in a subtle point of view shift that occurs when Julian enters the story. The relentless first-person singular narration momentarily switches into the plural:

I drank old-fashioneds in the apartment of my friend Julian. We talked about Worringer and Spengler. We gossiped about friends. Then we left to meet our dates. There was more drinking. We all climbed trees, crawled in the street, and went to a church. (Italics mine)

This run of plural pronouns occurs after a string of fifty first-person, singular ‘I’s’. The effect is striking. The only other time ‘we’ is used in the story occurs at the story’s end. I will return to this point below.

The narrator (and the story) appears suddenly conscious of other people besides himself. Soon after the Julian section, the narrator returns to talking about himself, about his basketball scholarship and his classes, but then another character takes the stage. His roommate (unnamed) suddenly comes forward for an extended sequence. There is a run of twenty-three verbs all directly linked to the subject of his roommate.

Though very intelligent, he suffered in school. He suffered with girls though he was handsome and witty. He suffered with boys though he was heterosexual. He slept on three mattresses and used a sunlamp all winter. He bathed, oiled and perfumed his body daily.

This section ends with the simple statement: “Then he killed himself.” The entire paragraph centers on this roommate. The narrative “I” does not appear once. In a sense, this section operates as an inset story, a brief but complete story on its own and focused away from the narrator. It would seem that the narrator has slowly become aware of other people, and this trend continues.

One of the most stirring, un-self-conscious passages comes soon after this ‘roommate string’, when the narrator sees Pearl Primus dance. The images expressed are carefully composed as he watches her dance accompanied by an African drummer:

Pearl Primus

“I saw Pearl Primus dance, in a Village nightclub, in a space two yards square, accompanied by an African drummer about seventy years old. His hands moved in spasms of mathematical complexity at invisible speed. People left their tables to press close to Primus and see the expression in her face, the sweat, the muscles, the way her naked feet seized and released the floor.”

Absent from this passage is the narrator’s recurrent narcissism. Gone again are the “I’s.” He was captivated by what he saw, and we are captivated by his description of it: the spasms of the drummer, the seizing and releasing feet of the dancer. These images hearken back to the Portuguese men in the fish factory, as something that affects the narrator more deeply than the rest.

Michaels uses these shifts in narration to reveal the narrator’s character more deeply. When the narrator comes forward significantly, we learn only facts, nothing of depth. Though none of the other characters, named or otherwise, compete for the reader’s attention, true development of the narrator’s character occurs by omission. By repeating the first-person, singular pronoun, ‘I’ over ninety times in this short (maybe 2000 words) story, and by making the narrator appear simply obsessed with himself, especially in the beginning of the story, Michaels generates an effective pattern: when the narrator recedes, the readers understands more. Character growth occurs. Michaels makes the first-person narrator such a prominent aspect of the narration that the effect, when ‘I’ is not used, is jarring. It becomes what Glover calls an “anti-structure,” a structure that works by its absence rather than its presence.

Closely related to the way Michaels manipulates character development is his deformation of point of view. There are two distinct ways that the point of view shifts. The first way has to do with time, the second with perspective.

The majority of this story is told in the past tense. “In the fifties I learned to drive a car. I was frequently in love. I had more friends than now.” Michaels signals at the opening that the story is being told from a distance, but this narrative perspective remains vague. It could be six months or it could be twenty years. The reader never learns. The story continues to use this narrative distance until the narrator breaks in from his perspective a few more times in the story.

I knew card sharks and con men. I liked marginal types because they seemed original and aristocratic, living for an ideal or obliged to live it. Ordinary types seemed fundamentally unserious. These distinctions belong to a romantic fop. I didn’t think that way too much.

The shift in tense here on the verb ‘belong,’ acts again from the narrative present-time. The sentence works thematically, shedding light on the story. Are we supposed to think of this narrator as a ‘romantic fop’? There does seem to be a disowning here, a disavowal of the younger, more isolated self from the perspective of the future narrator, the narrator looking back for purposes of telling this story, but the narrator quickly undercuts the disowning by telling us that he “didn’t think that way too much.” The use of the present tense also reminds the reader that this narrator is out ahead of this story somewhere, but the narrator remains vague and unclear, almost detached from the story he is telling. The present-time narrator interrupts the flow of the recollection four times but offers no real commentary or perspective on who he is now, or how this story has affected him. The effect of this interruption forces the reader to ask a lot of questions that will go unanswered in the story. We will never learn who this narrator is ‘now.’ We will never learn what effect these chronicled events have on the present narrator. We will only have questions, but the effectiveness of this story rests more on the questions it raises than those it answers.

Michaels also manipulates point of view with respect to the narrator’s perspective. Again, the abundant use of the pronoun ‘I’ creates an unusual effect in the story. There are two points when the narrator’s consciousness seems to merge with the circumstances around him, when the ‘I’ becomes a ‘we,’ and these two instances indicate a significant shift in perspective. The first, already mentioned, occurs with his friend Julian. The use of ‘we’ in this small section is underscored by the fact that this is also the first named character in the story (other than the aforementioned historical characters.) The use of ‘we’ occurs only one other time, in the penultimate sentence of the story, after he has gone down to the courthouse to protest the arrest of a friend.

I expected to see thirty or forty other people like me, carrying hysterical placards around the courthouse until the cops bludgeoned us into the pavement. About two thousand people were there. I marched beside a little kid who had a bag of marbles to throw under the hoofs of the horse cops. His mother kept saying, “Not yet, not yet.” We marched all day. That was the end of the fifties.

Michaels’ whole story builds to this tiny point of view shift. The narrator’s expectations are confounded; instead of forty like-minded people, there are two thousand. He notices the kid, and for the first time, he uses attributable dialogue, then the shift in narration: “We marched all day. That was the end of the fifties” This merging of the narrator’s sensibility with that of the other protesters reflects a structural complexity that, while anti-conventional, works to achieve an important effect. These narrative ‘wobbles’, whether in tense or number, signify shifts are occurring. Were this story told without them, its effectiveness would suffer.

The final variation from the conventional story involves plot. Michaels writes this story as an extended list. There is no apparent causality, no apparent connection between the events. What he substitutes for plot steps, however, are thematic repetitions. There are several examples of this in the story, but social unrest is one of the most important, and I think it works as one of the thematic repetitions that stands in for the absence of a conventional plot.

The fifties were a time of growing social discomfort with the established institutions of American life. The tension between the old and the new social realities may have exploded in the following decade, but the roots of that social discord reach back deeply into the decade Michaels chooses to examine. I think this history, though outside the text, is important to the consideration of the thematic repetitions I’m about to examine.

In the second paragraph, the first example of this social-discord occurs, and this example is related to the House Un-American Committee, or HUAC.

I attended the lectures of the excellent E.B. Burgum until Senator McCarthy ended his tenure. I imagined N.Y.U. would burn. Miserable students, drifting in the halls, looked at one another.

The narrator expects the campus to explode, but instead, there are only sad looks. Two curious things occur: the intrusion of the conservative government into the life of the narrator, and the impotence of the response (especially on the part of the narrator.) Later, the narrator is arrested and photographed, and though the alleged crime is not mentioned, we can surmise that it had to do with his growing social awareness. He has likely done something subversive, but nothing so bad as to merit the arrest. “In a soundproof room two detectives lectured me on the American way of life, and I was charged with the crime of nothing.” The soundproof room, the crime of nothing, juxtaposed with the American way of life, point to a growing dissatisfaction, however muted, growing. The next example involves Malcolm X, and how the narrator no longer had black friends after the black activist became prominent.

In Ann Arbor, a few years before the advent of Malcolm X, a lot of my friends were black. After Malcolm X, almost all of my friends were white. They admired John F. Kennedy.

The unstated premise is that the black friends became active and followed their ideals, while the white friends placed their hopes in the system. Later, the narrator mentions meeting Jack Kerouac, an iconic figure of the counterculture.

The final paragraph though, is most interesting. A friend is arrested at the HUAC hearings. He goes to protest this arrest (the second act in a row of supporting a friend) and “expected to see thirty or forty people like me,” but instead finds that “about two thousand people were there.” Compare this scene to the earlier encounter with the HUAC, when he “imagined NYU would burn.” By the end of the story, he acts. And others are acting with him. He joins the swirling mass of protesters. He becomes subsumed by them. The last lines of the story underscore this transformation. “We marched all day. That was the end of the fifties.” After ninety references to “I,” the story and the decade closes with “we.” His idealism, his expectation to be part of a small (thirty or forty) group, is met with the reality of a huge crowd of people. Suddenly, the narrator is reduced. He disappears and is absorbed by the crowd, and perhaps by the decades which follow. These ‘steps’ are not created through traditional plot devices, but rather through a subtle repetitions of social disharmony, most clearly represented by the two instances where HUAC is mentioned and by the references to counter-culture figures or circumstances.

Michaels radically alters the form of the short story in a number of ways. By turning conventional devices of character development, point of view and plot into alternative structures, he creates a difficult but emotionally ‘whole’ story. The specific images are all grounded in realism, but the structural devices of conventional stories are manipulated and deformed to create an anti-story, a story that works off of a list rather than a plot, a story that works without named characters, and by raising many more questions than it answers.

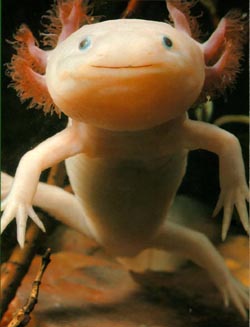

“Axolotl” by Julio Cortázar

“Axolotl” is a seven page short story told primarily by a first-person narrator who visits animals in a Paris zoo until he turns into an axolotl (a neotenic species of Mexican salamander.) Most of the narration occurs in the past-tense, though at times the story shifts into the present tense and also into the third person. During these shifts, the narrator-as-axolotl shifts also occur. There are only two characters in the story, the narrator and a zoo guard. The primary setting is the aquarium at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, and except for a short description of the city itself and a brief description of the library, the setting does not shift, though the perspective of that setting does, from outside the tank to inside the tank. There is only one line of dialogue in the story, spoken by the guard to the narrator.

The story opens with the narrator thinking about the axolotls then stating that he has turned into one. Then the narrator explains how he came to discover these creatures inside the aquarium at the Paris zoo. He feels an immediate and deeply personal connection with the axolotls, and he goes to the library and researches them. He begins to obsessively visit their tank, staring at them through the glass. His obsession at first seems mysterious, artistic, even resembling a love story. He visits daily, sometimes twice a day. The only other character, the zoo guard, coughs, and makes only one comment. The narrator begins to identify with one axolotl in particular, then, in a strange sequence, the human narrator becomes an axolotl. After this, a climatic reversal occurs, and the object (the axolotl) becomes the subjective narrator commenting on the new object (the human narrator from the first part of the story). The story ends with the narrator-as-axolotl looking out from the cage at the narrator-as-human, now transformed.

Cortázar creates a dramatic and narrative metamorphosis with the use of a shifting narrator. He accomplishes this playful transformation by manipulating the narrative consciousness of the story in very un-conventional ways. The point of view ‘bounces’ between the narrator-as-human and the narrator-as-axolotl—a transformation that occurs in three distinct steps. The dramatic, physical metamorphosis, from human to axolotl, parallels the actual physiologic metamorphosis of animals (and it represents an ironical reversal of reality, since the axolotl never undergoes metamorphosis and the creature remains trapped in a juvenile stage of development.) The narrator’s metamorphosis is dramatized through a sequence of narrative shifts until the transformation is completed. As the point of view shifts, the character shifts, the subject-object orientation shifts, and reversals of perspective take place. All these things occur in unconventional ways through the deformation of the point of view, a typically conventional device.

In the beginning, the narrator-as-human appears to be a typical first-person narrator:

There was a time when I thought a great deal about the axolotls. I went to see them in the aquarium at the Jardin des Plantes and stayed for hours watching them, observing their immobility, their faint movements. Now I am an axolotl.

Axolotl

From this opening paragraph, the reader might conclude that the narrator could be insane, he could be ironic, or he could be joking. The reader simply doesn’t know. What follows this opening statement are seemingly rational statements about the narrator’s growing obsession with the axolotls. While strange, nothing about his obsession is unconventional, except for the closing sentence of the first paragraph: “Now I am an axolotl.” This sentence triggers the reader to think that something very unusual is going on, and Cortázar’s decision not to comment on it underscores the weirdness of the story.

The next distinctly odd shift comes in the form of a parenthetical statement amidst a description of the animal cage: “The axolotls huddled on the wretched narrow (only I can know how narrow and wretched) floor of moss and stone in the tank.” Which ‘I’ is talking? The narrator-as-human wouldn’t know this fact, but the reader can’t be sure (yet) whether or not the narrator-as-axolotl will appear as a distinct voice. We’ve begun to see a narrative metamorphosis, the transformation from human narrator to axolotl narrator, but in this stage, both narrators coexist. Another example of this larval stage occurs when the narrator-as-human is staring into the cage and the perspective flips:

Once in a while, a foot would barely move, I saw the diminutive toes poise mildly on the moss. It’s that we don’t enjoy moving a lot, and the tank is so cramped—we barely move in any direction and we’re hitting one of the others with our tail or head—difficulties arise, fights, tiredness. The time feels like it’s less if we stay quietly.

It was their quietness that made me lean toward them fascinated the first time I saw the axolotls.

The first sentence is in the human perspective. He’s watching the movement from the outside. Then the divide is crossed and the perception becomes that of the narrator-as-axolotl. The point of view is now fluidly jumping across the narration divide between human and axolotl but the two narrators remain distinct. Then he breaks the paragraph and immediately returns to the narrator-as-human point of view. ‘We’ is replaced with ‘them.’

The final shift occurs near the end of the story. The narrator says, “So there was nothing strange in what happened,” though the clear irony of this statement makes the next sequence all the more strange. Once again, the narrator-as-human is staring into the tank of axolotls, his face pressed against the glass, when the final transformation occurs:

“Only one thing was strange: to go on thinking as usual, to know. To realize that was, for the first moment, like the horror of a man buried alive awaking to his fate. Outside, my face came close to the glass again, I saw my mouth, the lips compressed with the effort of understanding the axolotls. I was an axolotl and I knew that no understanding was possible. He was outside the aquarium, his thinking was a thinking outside the tank. Recognizing him, being him himself, I was an axolotl and in my world.”

The narrator-as-axolotl now refers to his human self in the third-person construction. The possessive pronouns shift again, from ‘my face’ to ‘his thinking.’ This metamorphosis completed, the narrator-as-human recedes entirely, becoming the object—the perceived animal—and the narrator-as-axolotl takes over as the subject for the rest of the story.

Cortázar has taken a traditional device, point of view, and deformed it radically. The narrator shifts occur fluidly, without any real conventional transitions like section breaks, scene shifts or asterisks. The transitions occur in mid-paragraph or even mid-sentence. Cortázar deforms the traditional device of consistent point of view and establishes a pattern that parallels dramatically the physical metamorphosis of nature.

But point of view shifts are not the only ‘deformations’ that occur in this story. Consider what other conventional devices are absent or backgrounded in this story: 1.) Characters. There are no real characters except for the narrator, and even he shape-shifts early and often. We know almost nothing about this narrator’s life outside the aquarium and no other people are even mentioned, such as family, friends, or lovers. 2.) Conflict. No force resists the narrator’s movement. The guard offers only the slightest resistance but does nothing to intimidate or stop the narrator. Nothing else (such as reason or science) interferes or prevents this most unusual transformation. 3.) Time. While there is forward movement of time in this story, it’s unclear when these events have taken place. We don’t know where the narrative time grounds itself with respect to the dramatic events presented in the story. 4.) Plot. While there is a semi-plot in the conventional sense, (“A unidirectional series of causally related events”: He obsesses on, then becomes, an axolotl.) the only real action in this story is staring, looking and gazing. There is very little physical movement, very little in the way of dramatic action. With so much missing, it becomes important to understand what stands in place of these holes, what works to undergird the missing framework.

Cortázar builds this story by the careful selection of recurring images and by ‘splintering’ those images to create a web of related images that effectively stand in for character, conflict, time and plot. Cortázar uses patterns instead of more recognizable devices and Glover, in his essay “Short Story Structure,” says that the patterns can help establish a quality of literariness in a story or novel, which works against verisimilitude.

“Now add to this some sense of how image patterning works: an image is something available to sensory apprehension, or an idea, as in Kundera, which can be inserted into a piece of writing in the form of word or words. An image pattern is a pattern of words and/or meanings created by the repetition of an image. The image can be manipulated or “loaded” to extend the pattern by 1) adding a piece of significant history, 2) by association and/or juxtaposition, and 3) by ramifying or “splintering” and “tying-in”. Splintering means splitting off some secondary image associated with the main or root image and repeating it as well. Tying-in means to write sentences in which you bring the root and the split-off image back together again. “

One pattern we’ve already seen in Cortázar is a point of view shift. The next pattern will be in the form of a primary image, the eyes, which Cortázar splinters and effectively ties-in repeatedly throughout the story.

“Above all else, their eyes obsessed me,” the narrator says. “‘You eat them alive with your eyes, hey’ the guard said laughing.” (Notably, this is the only line of dialogue in the entire story.) The word ‘eye’ repeats seventeen times, then splinters off into a variety of forms, including disc, orb, orifice, brooch, iris, and pupil. The main image also splinters into images of glass, transparency, color (especially gold, pink and rose) and shape. The verb ‘to see’ is repeated fifteen times, and splinters into other verbs, including watch, observe, look, peer, notice and gaze. The narrator’s obsession centrally recurs through images associated with seeing, which, in the end, leads to his metamorphosis. The earlier point of view shifts also occur through a primarily visual transformation. The narrator-as-human, which opens the story, observes intently the axolotls in their cage. The story concludes with the narrator-as-axolotl watching the human through the glass until he disappears. “The eyes of axolotls have no lids,” the narrator says at one point, a most fitting image to close out this reversal.

The reader is meant to witness a transformation, to read (visually) a story about a man turning into an axolotl and pronounce a judgment about the story. This would seem to be, in a thematic parallel, the fate of the fictional axolotl as well: “The axolotls were like witnesses of something, and at times like horrible judges. I felt ignoble in front of them; there was such a terrifying purity in those transparent eyes.” (p. 7) Cortázar renders this transformation through a shifting point of view and through repeated and splintered visual images. He concludes this story with a wonderfully playful passage that reflects back on the strangeness of the story that has been told. This passage occurs in the narrator-as-axolotl mode:

“I am an axolotl for good now, and if I think like a man it’s only because every axolotl thinks like a man inside his rosy stone semblance. I believe that all this succeeded in communicating something to him in those first days, when I was still he. And in this final solitude to which he no longer comes, I console myself by thinking that perhaps he is going to write a story about us, that, believing he’s making up a story, he’s going to write all this about axolotls.” (p. 9)

Conclusions:

Outlier stories work in defiance of conventional forms. They operate without the formal architecture and yet still attempt to function with the logic of a story. They are, after all, not essays, not poems. For all their deforming variance, the consciousness of the outlier remains a story. At times they alter conventional devices in strange ways, as both Michaels and Cortázar do with point of view. At other times, they substitute patterns and repetitions to stand in for conventional forms. Glover summarizes this well when discussing aspects of the experimental novel in The Enamoured Knight:

Essentially, experimental novelists do what Bakhtin did and flip an aspect of the strict realist definition to make a new definition. The late American experimentalist John Hawkes once said that “plot, character, setting and theme” are the enemies of the novel, while “structure—verbal and psychological coherence—is still my largest concern as a writer. Related and corresponding event, recurring image and recurring action, these constitute essential substance and meaningful density of writing.” Generally speaking, plot, character, setting and theme are the structures that promote verisimilitude in a work of fiction, whereas repetitions, image patterns and subplots, the sorts of repetitions and correspondences Hawkes is referring to, while necessary in a work of art, tend to undermine verisimilitude. Such structures promote coherence, focus and symmetry in a way that insists on the bookishness of the work rather than concealing the author’s guiding hand.

“Experimental novelists intensify these aesthetic patterns or accentuate literary process and technique or invent anti-structures designed to destroy the structures of verisimilitude.”

These substitutions, deformations and estranged methods can lead to a new way of appreciating the conventional story and can lead to more expansive understanding of the story form itself.

—Richard Farrell

Works Cited

Cortázar, Julio. Blow Up & Other Stories. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985)

Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory. (Minneapolis: The University of Minneapolis Press, 2008)

Glover, Douglas. The Enamoured Knight. (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive, 2005)

Glover, Douglas. Notes Home from a Prodigal Son. (Canada: Oberon Press, 1999)

Glover, Douglas. “Short Story Structure: Notes and an Exercise.” (The New Quarterly, No. 87, Summer 2003)

Michaels, Leonard. A Girl with a Monkey. (San Francisco: Mercury House, 2000)

Shklovsky, Viktor. Theory of Prose. (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive, 1991)

Sumerlian, Leon. Techniques of Fiction Writing: Measure and Madness. (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969)

Barthes, in his famous essay “

Barthes, in his famous essay “

What had happened? The room seemed really tiny and the smell much less mildewy than before. There were hooks on the wall to hang a broom and mop on. In one corner, two buckets. Along another wall, a shelf with sacks, boxes, pots, a vacuum cleaner, and, propped against that, the ironing board. How small all those things seemed now—he’d hardly been able to take them in at a glance before. He moved his head. He tried twisting to the right, but his gigantic body weighed too much and he couldn’t. He tried a second time, and a third. In the end he was so exhausted that he was forced to rest.

What had happened? The room seemed really tiny and the smell much less mildewy than before. There were hooks on the wall to hang a broom and mop on. In one corner, two buckets. Along another wall, a shelf with sacks, boxes, pots, a vacuum cleaner, and, propped against that, the ironing board. How small all those things seemed now—he’d hardly been able to take them in at a glance before. He moved his head. He tried twisting to the right, but his gigantic body weighed too much and he couldn’t. He tried a second time, and a third. In the end he was so exhausted that he was forced to rest.