After all, that was only a savage sight while I seemed at one bound to have been transported into some lightless region of subtle horrors, where pure, uncomplicated savagery was a positive relief, being something that had a right to exist—obviously—in the sunshine.

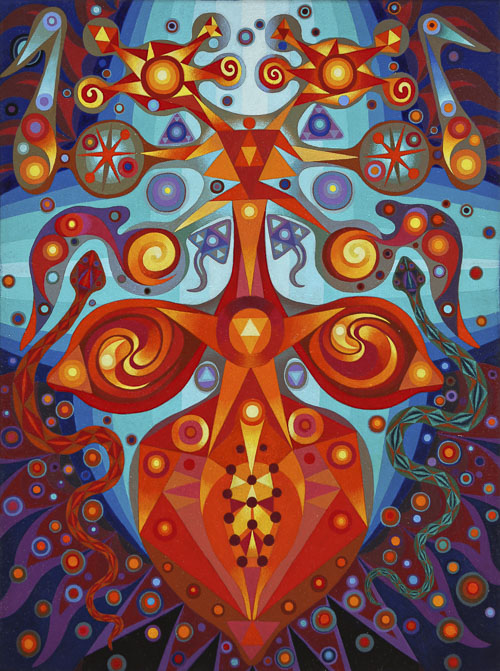

In Heart of Darkness, Marlow, captain of a slight and halting steamer, after many weeks navigating the treacherous Congo has reached his destination deep inside Africa, the inner station of the trading company where chief agent Kurtz presides, Kurtz the emissary of profit and reform, a model of the hopes of Europe, the leader of the native tribes, a genius at acquiring ivory. The subtle horrors are as much the fruit of Kurtz’s efforts as of what lies within the jungle, but also are Marlow’s own black projections on its darkness, not returned. The pure savagery brought to light is Kurtz’s symbolic gesture, heads of native rebels he had cut off and put on stakes, lined before the station house. The heads, however, do not face outward to warn tribesmen from transgression but inward towards the house, where Kurtz can contemplate their gaze.

I kind of picked up the thumbs-up from the kids in Al Hillah. Whenever I get into a photo, I never know what to do with my hands, so I probably have a thumbs-up because it’s just something that automatically happens. Like when you get into a photo you want to smile.

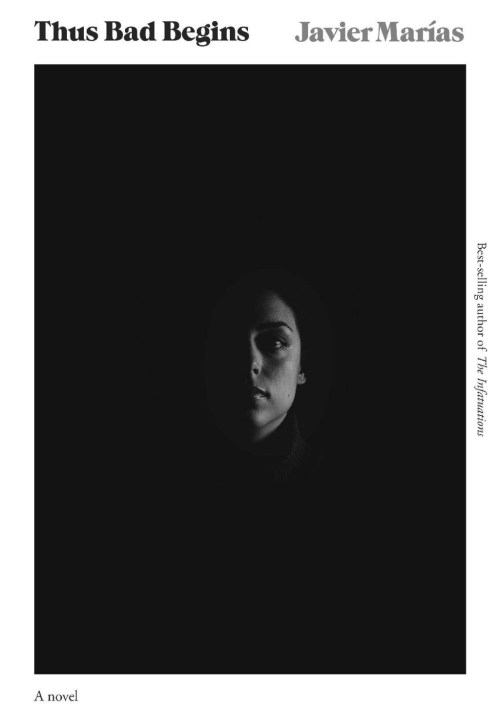

We contemplated her gaze and that gesture, at least for a while, as she faced us, the smiling Army Specialist Sabrina Harman, who aided in the gathering of intelligence at her station, Abu Ghraib, the prison deep inside occupied Iraq. Or rather we saw her in pictures brought to light after years of subtle horrors in a war we thought was going well and whose mission we were sure of, the pictures bringing a clarification, an obviousness, a relief, their own kind of rightness. She does not look at what she smiles over or what she thumbs up but we see them, the pile of grotesquely hooded, naked men, the blackened corpse.

Was it over a decade ago or a century? It is hard to keep track of time in a world that recreates itself afresh every day. Somehow the Abu Ghraib pictures have been washed aside in the stream of things, of other disturbing images that continue to flow past. The distance between our purpose then and our behavior, between our professed ideals and the horror, however, has not been closed and the pictures still haunt me. I have not found a way to explain or discharge them, or come to terms with other lingering subtleties in a world where I do not know where I stand. I have no idea where we’re headed, though the world tells me we are moving forward. I do not know what to with my hands either.

Against all the sharp narratives that have played out the last years, in battlefields imagined on screens and in the world actual, it is to the muddy story about a captain who just goes up a river and back I most often return, a journey that resembles my own. I have only observed the horrors of history, of the present, from a distance, yet they still belong to my world and I have felt their currents, as well as sensed all that lies beneath them, unseen, unknown. Like Marlow, I work for a trading company of sorts—we all do—and my station is modest and my task simple. Like Marlow I have been on a long trek and kept my shoulder to the wheel. I think I am good person, or good enough, and have provided some service, though I know not to make anything of either or rest easy. Like Marlow I keep my distance, like Marlow I do not have any answers, like Marlow I do not forget easily. I have yet to meet face to face, however, anyone with the revelatory power of a Kurtz.

Kurtz’s virtue is that he can front the terrors that lie without and he holds within, face their contradictions, and feel their full effect. This is what redeems Kurtz in Marlow’s eyes against all others in the company who stumble through their corruption without pause. And Kurtz has a voice, though we hear few of his words, most significantly the two that refer to his black vision. Marlow stays detached—he has to—and observes the horror through Kurtz, one step removed, just as Conrad has us observe Marlow, when he does not speak, through the narrator, adding one more frame to the layering of frames. There was a morbid fascination, but Sabrina Harman’s reaction was one of mute disjunction, not approval, a frozen reaction to the horror she witnessed but could not contain. No one framed her, though she was following orders.

I would like at last to be able to look into the heart of things, within, without, and come to an understanding, though I have got no closer over the years and have yet to find a frame. I do not know what I project on the world, nor can separate that from what it returns. And I would like to find a solid voice I can live with, that sustains me and helps me reach out, though still it wavers. Like Marlow I need to keep distance without losing sight so I can find perspective and maintain it. There are times, however, I see myself as Harman, transfixed, stunned and speechless, though without a smile.

The thumbs up—it is our universal gesture now for everything, that graces all we have seen and done, that we sign above where we’ve been and where we are headed, whatever we happen to be doing at the present moment, which, along with an open face and guileless smile, the captured gaze we show the world and that defines us, has replaced the two-fingered sign of benediction, pointing to a another kind of transcendence..

.

As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Donald Rumsfeld. His remark received the status of pop wisdom and circulated widely.

Any life is a mission and every mission has a life, each a journey into the unknown, each a story whose plot charts the trajectory of beliefs and desires against the ground of reality over the course of time. It is the tension between the first and the latter that propels the action and moves us through the telling, leading us to climax, the locus of dreams and nightmares.

Marlow as a boy was fascinated by the mystery of Africa, as was Conrad, who made a similar journey upon which his novel is based, inner Africa then a white, undifferentiated patch on the map, a blank slate that stirred his curiosity. Rumsfeld, our Secretary of Defense, talked about what we know and what we do not know in a press conference to justify the invasion of Iraq based not on the possibility of the presence of weapons of mass destruction but upon the possibility of possibilities unknown, the blank space where he plotted his course and let his imagination sail.

There were no weapons of mass destruction.

What do we know we know?

We live in a culture that believes in itself and in us, in the value of our individual existence and our collective endeavors. We also recognize the necessity of managing material needs for survival and growth, which can lead to compromise and sacrifice. It is difficult to put our ideals and the physical world together. War, when deemed necessary, brings its own realities that unsettle any equation. The temptation is to consider ideals airy and insubstantial, thus suspect, and practical decisions defensible because they are grounded in reality, to favor realists over idealists, though ideals can have concrete manifestation and reality does not make sense without some kind of basis. Nor can concrete action be promoted without abstract justification or even be coherent. Then there are our desires, which do not fit easily with either reality or ideals, but flit fretfully between them.

Conrad’s Belgium, like Europe, was a champion of progress and enlightenment that it wanted to pass on to the peoples of the rest of the world to free them from misery and confusion, though not raise them to its level and give them power over their own lives. It also had a stake in claiming territory in Africa the other European countries were carving up in their dreams of conquest. And Africa had ivory, a symbol of purity, the mystical white growth of the tusks of huge beasts, a substance that is hard but suggestive to the touch and can be carved with delicacy and precision into curved and intricate shapes that endure, that was used to make billiard balls and piano keys and inlays and jewelry and knife handles and figures of saints, which at the time returned enormous profit.

We inherited the ideals of the Enlightenment, which we wish to pass on by example. We also debate our relationship with imperialism, where we struggle with distinctions. Of course there is our need for oil to warm and transport us and create our synthetic products, where we all are more involved than any of us might like to concede. Then there was the attack in New York and the fallen towers, the necessity to protect ourselves from invaders as well as appease whatever vestiges remain of tribal revenge, which shouldn’t be taken lightly. Bin Laden and Afghanistan, however, were soon abandoned, and plans had been made for decades to destabilize the Middle East and gain control of world oil supplies. Rumsfeld made Iraq a priority well before the towers fell, which event provided pretext for the invasion.

Past and present, our world has depended on the transmutation of pliable substances and unsettled values, and it is difficult to find stable ground.

Justification was provided, however, to allow action and keep our ideals intact, based on essential difference. Africans were seen as savages, thus fell outside standards reserved for civilized people. Kurtz himself wrote an eloquent tract for the International Society for the Prevention of Savage Customs. The difference was supported by concrete observation and physical proof, the contrast between skin white and black. For us the difference was that between free people and terrorists who oppress, which the Bush administration used to freely suspend the guidelines of the Geneva Conventions and allow brutal interrogation at Abu Ghraib, this supported by concrete evidence of the violence turned against us by the people of occupied Iraq, though we found no links between Saddam’s regime and Al Qaeda. Instead we brought them in.

Both differences, however, are based not on known knowns, or even known unknowns, but unknown unknowns. Marlow never penetrates the jungle to observe the people and their customs. He does not know the language, nor does Conrad give the natives a voice, except a handful of words they speak in broken English, the last to inform us of Kurtz’s death. Our government listened to no one except Chalabi, the Iraqi exile they wanted to put in power, and knew almost nothing about the Arab people’s beliefs and desires and customs, only just enough to humiliate them. Intelligence gathering had to come later, at Abu Ghraib. In Marlow’s story all we see are shots fired blindly into the jungle and dilapidated outposts at the fringes; in ours we largely saw our mechanized race through the desert, our guided missiles flying through the air, whose cameras showed us their blind destruction, and our command post at Saddam’s Palace, surrounded by tall concrete blast walls that separated it from the rest of Baghdad, from which civilian leaders of the occupation only timorously ventured.

And we saw what we now know we know but still strains belief. In Conrad’s novel Africans are taken from their villages, some set against the others, most forced into labor and chained, starved, beaten, and left to die. In real life Congo Free State, women, men, and children were freely mutilated. Failure to meet production quotas at the rubber plantations was punishable by death, and King Leopold ordered the hands of the guilty be cut off and sent back to Belgium as proof of execution. Natives also saw their children slaughtered, their villages burned. In the some two decades of Leopold’s occupation, the population decreased by an estimated ten million, this caused by murder, abuse, neglect, disease, and drastically fallen birth rates.

During the decade of the war in Iraq and since, civilian deaths from violence runs almost two hundred thousand, most caused by the sectarian violence we unleashed in a country we occupied but could not control, the total still rising. At Abu Ghraib, where thousands were detained, most civilians who posed no threat, prisoners were deprived of food and sleep and warmth; burned, beaten, flooded, and attacked by dogs; hooded with sandbags or forced to wear women’s panties on their heads; made to stand naked separately or huddled into piles; and raped or forced to commit sexual acts with each other or sodomized by a broom handle and a chemical light stick. The pictures we finally saw were part of the process, taken to double their exposure and multiply the humiliation. Specialist Harmon took one of the pictures of the hooded man standing on a box in a shower, loose wires attached to his fingers to make him fear he might be electrocuted if he stepped off, his arms raised high by his sides like wings or like those of another well-known figure, providing us perhaps with the most clarifying image from the war. The corpse she thumbed up had been beaten to death and put in a body bag and packed with ice, waiting to be taken out secretly to cover up his murder. Then there were the Abu Ghraib pictures we did not see because they were not released, along with the unseen torture at Guantanamo Bay and rendition at unknown places.

It is the excess of reality, known knowns, that taxes belief, not any buried secret or flight of ideals. Not seen, not known, not even known they were unknown and stretching belief further, were the horribly obvious ironies that sent our values soaring, that white civilized people savagely brutalized blacks they labeled savage, that our torture was carried out in the very prison Saddam Hussein had created to terrorize his own people, whose freedom and well being had become the final justification for our invasion.

Or that when we entered the heart of darkness we were looking at ourselves..

.

America stands against and will not tolerate torture.

President Bush to the United Nations, well after the fact.

Exterminate all the brutes.

The note Kurtz scrawled with a shaking hand at the end of the pamphlet he wrote for the International Society for the Prevention of Savage Customs.

Marlow returns to Europe with nothing to sustain him other than the memory of Kurtz, who helped him see more clearly what he didn’t see well before. He is more distant from the world, or rather more aware of his distance. One’s journey to find oneself in the world begins and ends at home, perhaps to realize one has never left it, or that one has no home to return to. But the novel ends without conclusion, without resolution of plot, and Marlow himself reaches no larger understanding.

My challenge, then, is to see if I can pick up where Marlow leaves off. But I feel naive yet at the same time presumptuous for looking at what is so obvious and attempting to explain what should be self-evident, as well as perverse for looking at it again, the obviousness made no less obvious by its magnitude, or no more. And it is difficult to take on the obvious, what offends in its absurd and utter simplicity, with a straight, with any kind of face, and not lapse into sarcasm or ridicule. But there I run the risk of trivializing my opposition without effect, who simply can dismiss me, and alienating anyone else who might listen. Already I’m beginning to lose myself. But there remains the perplexing problem, perhaps not obvious, of why the obvious isn’t obvious.

So I persist and look at the severed head that rests on a pole and stares back at me, and ask the obvious question: Why wasn’t demolishing Abu Ghraib a first priority? Given how efficiently the Bush administration managed our perception of the war with its manipulation of the media, why weren’t we immediately shown the razing of its walls? The images could then have been coupled with those of pulling down Saddam’s statues, which we did see many times. The act would have brought cause and effect together and provided a conclusion that would have at least given the appearance of validity to their justification for the war—saving the Iraqi people from oppression—which might have satisfied the rest of the world and us, at least for a while. Doing so, however, might not have served their real purpose. It is also possible they did not understand the terms of this argument. Another possibility is that we weren’t especially interested in seeing that footage.

Bush did offer to tear down the prison, but Ghazi al-Yawar, the interim Iraqi president, refused because he couldn’t justify the cost. Given Yawar’s tenuous command and our administration’s overwhelming influence, it is impossible to believe he could not have been persuaded otherwise. Also the Abu Ghraib pictures had already been aired, so Bush was only trying to control damage, and his proposal was to build a modern prison in its place, which would have better suited his plan.

I can go no further, if I hold any human value, without stepping back, separating myself, and standing opposed, which is what I did at the time, a decade of total disaffection with our government, of skepticism about government itself. But to stand apart I need a justification to support my foray into interpretation and keep myself intact, and the justification will require creating my own essential difference: I am moral and they were not.

Our leaders were ruthless and corrupt, and acted without conscience, looking only to their own interests—both Bush and Cheney’s roots ran deep in oil—and those of the wealthy few who shared them and stood to profit from the war. Their only motive was to protect those interests and extend their power. There was the risk, however, that by ignoring the ideals of democracy they might undermine their standing in the world and the basis that kept them in power during elections. The only way they could justify their action was to create the difference between free people like themselves, like all of us, against terrorists, not like any of us, but they had no interest in freeing anyone. They needed a prison, and stuck with Abu Ghraib because it was convenient, so they could maintain control and gather necessary intelligence as well as intimidate the people of Iraq through fear. They had to maintain distance from the torture by keeping the details unknown so they would not be implicated or caught in contradiction as long as they could. By the time their hypocrisy was exposed, if that ever happened, it wouldn’t have mattered because by then they would have had control, what was done was done and could not have been reversed, and there was no other power at home or, with the fall of the Soviets, in the rest of the world strong enough to oppose them.

That interpretation to some may smack of glibness and political bias, and often leads to such accusations. It has always been hard to make it stick. Yet there is so much to support it and little that contradicts. Still, it doesn’t account for their behavior. Understandably they rushed to war and did not want to build a broader coalition. Time lost and shared participation might have weakened our support and their grip. What it does not explain is their haste. They likely did not have to worry about losing our support, not after 9/11. The Vietnam syndrome had run its course, and the war in Afghanistan was well received. If they did have to worry, they had created the fear of more attacks on us that would have bolstered our support if it flagged. So they ripped through Iraq, facing little resistance because Saddam had little resistance to offer, destroyed the regime, and planned a quick withdrawal, yet had no strategy for occupation, which makes no sense at all because they ran the risk of losing what brought them to Iraq in the first place, control of its people and their oil. And still left out is the excess of violence at Abu Ghraib, where, by so many counts, most of the intelligence gathered was of little use and often false. Tortured men will tell you whatever you want to hear.

Unless they were worried they might lose resolve themselves, that their justification, their distinction, might lose momentum. There may be a categorical mistake in assuming anyone can act without conscience, however perverse the outward signs. Also a political interpretation rests on the assumption their behavior was rational and they knew what they were doing. There is another way to understand their actions that takes us further into darker places, and I need to make another distinction to go there: I am sane and they are not.

Erich Fromm, in The Heart of Man, explains how our natural aggressive urges, our love of ourselves, and our affection for others, unchecked, can run rampant and grow malignant into necrophilous, narcissistic, and incestuous formations. In the powerful, the three can merge and lead to a syndrome of decay, where destruction becomes an end in itself and source of delight, as we saw in Europe the last century. Leaders need the support of their followers, of us, to build power, and do so by building our attachments to sterile things and hollow abstractions that flatter and melt reserve but do not strain us with difficulty, investing both with meanings they cannot hold, meanings that avoid meanings and deflect troubling questions. Stronger incentive is still needed, however, along with concrete proof, so leaders appeal to our sense of rightness by setting us against those who are not right, less human, or not human at all, and to make the argument conclusive, set us against those who can be readily identified and who are weaker and can be easily disposed of.

The only way the process can work is to remove the difference from reality and keep the unknown unknown so we do not see into hearts of those we oppose even as we attack, or see who we really are and what we are really doing. Otherwise the edifice of destruction loses its foundation and collapses. No wonder the statue of Saddam had to come down first. But it is difficult to maintain the illusion and keep the unknown unknown, yet the only way to support it is to push it further and step up the attack. Perhaps a guilty conscience did come into play, which only would have increased the strain, and with the strain, the necessity to put that voice aside and return more viciously to their argument. Proving superiority not only leads to paranoia and sadism, it depends on them.

And Rumsfeld’s logic of unknown unknowns was a spiraling ascent into paranoia. By controlling all intelligence, bypassing standard channels and having all intelligence run through him, accepting what fit and rejecting what did not yet at the same time removing himself from other intelligence, he was left to his own devices and worst fears. Perhaps he was merely being calculating when he thought he could pass off on us the reports of yellowcake uranium from Niger or the purchase of aluminum tubes made in China—both which might have been used by Saddam to develop nuclear weapons, both reports quickly rejected by the intelligence community worldwide—but his plan depended on weapons of mass destruction, so he bracketed them in unknown unknowns yet acted as if they did exist. He needed Saddam to have active ties with the terrorists, though Saddam had no use whatsoever—they only would have weakened his position—so Rumsfeld left known knowns, Bin Laden and Al Qaeda, behind to chase the phantoms. Saddam’s paranoia has to be factored in, along with his smoke and mirrors, but the only way Rumsfeld’s scheme works is to take them at face value and not try to see past them, assuming he could make that distinction. Meanwhile pending, what might have been the greatest deterrent to the mission and helps explain his haste, was Saddam’s offer, once he saw our forces mass, to bring inspectors in—he was begging—and show he had gotten rid of the weapons of mass destruction for the obvious and convincing reason that he did not want to give the U.S. cause to invade and lose his power.

The racial difference of Conrad’s day had one advantage: positing savagery into color provided obvious identification to clarify the European mission and even open the possibility, however immense the task, of a total solution. Terrorism gave no such advantage, as the only way to identify terrorists from non-terrorists was by their behavior, or, in the absence of such behavior, signs to suspect possible terrorist behavior, and if those could not be found terrorists had to be created. Perhaps there was a racial element involved as well, but then the search spread here at home with the endless surveillance. By keeping the details of Abu Ghraib unknown and propping up the terrorist distinction, the Bush administration allowed the violence to go unchecked, and without definite limits there was no way to complete the mission and close the circle as it was impossible to know when to stop. There is no telling how far the torture might have spread had the pictures not turned up.

One way to interpret their plan for a quick retreat is that, unconsciously, they wanted to escape the terrifying strain of what they envisioned. Or perhaps they wanted to pass the violence off on someone else but instead got stuck. Either way, the evidence points to wholesale destruction as the end result, consciously planned or not.

Somehow, in this context, I have to find high ground to better see and chart a clear course. But if I divest myself of my government I remove myself from power, without even a thought of representation or possible action unless I discover or create a space outside it. To consider myself moral leaves me with a burden that is difficult to bear alone, where it is too easy to stumble, the burden made enormous by the enormity of the abuse I try to face. I will always have to walk stiffly erect on a narrow path. To consider myself sane in the face of monstrous insanity removes me from my own internal debates and narrows the path further, the path already twisted by pursuit of the monsters it created for me, ever present.

But our leaders were somewhat genial men, not charismatic tyrants, who at least feigned humility, and they genuinely wanted our support. And their appeal, however conflicted, was for freedom, not conquest, which might have been sincere. Also they knew they needed us, as we could could topple them in the next election if they fell out of our favor. We love our freedom and want to feel good about ourselves, about our attachments to our reflexive devices and to each other. The fall of the towers might most have upset us when we realized what they did not support and how much they did not support it. Or what upset us was what we didn’t know but lay hidden in our own unknown unknowns, which vexed us even as we fled them. We, so many of us, believe the purpose of government is to turn us loose and set us free. We want to protect our self-interest and the interests of those who freely gather wealth. The market collapse at the end of Bush’s second term did not take us to Wall Street but elsewhere to find causes. And what distinctions do we make? Savagery is not rejected but openly embraced, an appetite fed endlessly on our screens in an unending crescendo of climaxes. A case could be made that we weren’t misled by tyrants, but rather with open hearts shaped the men we elected to represent us, then gave them a free hand.

Irony requires a context, and if none of us, our leaders or the free people of the U.S., saw the irony of Abu Ghraib, it may have been because we did not have one. Either we didn’t want to see the irony or we simply did not understand it.

I need to step back further and make another distinction, but I am running out of room.

I have gone too far, I haven’t gone far enough. Reality is more complicated. Reality is always more complicated, though complexity might have been pursued in order to avoid it. The Iraq invasion rested on decades of pressing concerns along with questionable and ambiguous involvement with allies and enemies alike, themselves questionable and ambiguous, including American covert support of Iraq in its war against Iran where Saddam did use gas, that support not stopped when he used it against Iraqi Kurds. Or perhaps our leaders just got lost in the vast complexity of what they were trying to do. Factoring in incompetence offers some relief. To deny psychological or moral interpretations, however, is to concede values have no influence and that our minds do not come into play. That the Bush administration really believed, that we believed, with all our hearts, that by toppling Saddam’s regime and pulling out we would build allies in the Middle East and restore world order, that the Iraqi people would welcome us with open arms and, left alone, follow our example and build a democracy of free people, that oil would freely flow once more—does not contradict the moral and psychological interpretations, or, if it does, sends us all into chaos, which might be where we are.

.

Marlow falls silent without finishing his last thought, leaving it in ellipsis, then sits apart from the other men on the deck of the cruising yawl on the Thames where he has told his story, returning to a cross-legged position, his back straight, arms down, and palms out, like a Buddha. Behind him, the brooding gloom of London. Before him, passage to the open sea.

But Marlow ultimately is a practical man, more occupied with managing his life than understanding it. Managing, in fact, is his answer, as, in a version of Freudian sublimation, he believes one should find oneself in one’s work, though he distances himself from the value of the work he performs. Efficiency is the key, and his main criticism of Kurtz is that he lacked restraint, that he couldn’t control the primitive forces inside him, inside all of us, and in nature itself, both forces coming together in Kurtz, corrupting and destroying him.

Freud in his later work, trying to account for the destructive course the world had taken, speculates that guilt from the conflict between our collective conscience and our dark, inner urges caused the malaise, the force of our desires unconsciously working on the guilt and taking a malicious turn.

What has held us back the last century, what have we not openly, freely tried? What does anyone feel guilty about now?

He also debates a death instinct, somehow somewhere inside us, maybe throwing up his hands.

Fromm prefers inside us a lighter, more creative force, which, when corrected by objective knowledge gained from science, might lead us from self-absorption and self-destruction.

What has our creative force brought to light, or our science? What hasn’t been explored by science in the mind, in nature? What hasn’t been diminished in both by the search?

All three, Marlow, Freud, and Fromm, posit some unconscious force, making a thing of the question they are trying to answer and thus avoiding it, leaving it in unknown unknowns that continue to haunt. And they miss what escapes them in their pursuit, what frightens us yet moves us and gives us the terror of hope—

There is nothing in the heart of darkness, except, perhaps, the heart.

I reread Heart of Darkness not looking for answers but a place to linger, and it is the novel where I most feel at home. The meaning of the story, as the narrator tells us, lies not in the core of the plot but outside it, this meaning enveloping it with an indistinct yet present glow, like a halo. It is the glow that draws me and keeps my doubts alive as I wander through a world only dimly perceived and try to navigate the jungle of Conrad’s thoughts, and of ours.

I am human and that matters. It is always the starting point and the point to which all journeys should return.

But I wonder if my best course now is not to sit apart, like Marlow, away from all fears and desires, and rest with the understanding that does not try to understand, the voice that does not speak.

There are moments, however, I am moved by bright visions and red passions, and I hear fresh voices from a distance speaking a strange language, and they come, and they gather, massing, and I join them, and they join me, and I lead them to light, and words come, and I hear a beating in dark places that matches the beating of my heart, faster, faster…

— Gary Garvin

.

.

Notes and Selected Readings

It is difficult to know what can be taken for common knowledge when so much still remains disputed and denied, but all factual claims in this essay made have been extensively researched and supported elsewhere. Another irony of the war is that it has taken careful, responsible writers years of painstaking research to discover what happened so quickly and was hidden so long.

Seymour Hersh, in Chain of Command, provides details on the abuse at Abu Ghraib and traces the chain of command involved, as well as reviews other matters touched on, such as the questionable evidence for Saddam’s ties with Al Qaeda and the existence of weapons of mass destruction. He cites a 2003 poll that showed 72% of the American people believed Saddam was personally involved in 9/11. To what extent the poll reflects the effectiveness of the Bush spin on the war or our own desire to make the connection would make an interesting study, though it’s unlikely the two factors could be sorted out.

At least one operative knew Conrad. Hersh describes the clandestine special-access program (SAP) that was created to track down terrorists. Few were aware of it. According to one former intelligence official, “We’re not going to read more people than necessary into our heart of darkness. The rules are ‘Grab whom you must. Do what you want.’”

George Packer, in The Assassin’s Gate, also reviews the events and influences leading up to the war and our subsequent occupation, our isolation and detachment during that time. He cites an early draft of the Defense Planning Guidance, written in in 1992, commissioned by Dick Cheney, then Secretary of Defense, and overseen by Paul Wolfowitz, then undersecretary for policy, which states: “Our first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival.”

So many of us quickly leap to accept conspiracy theories while others too quickly reject them out of hand. Peter Dale Scott, in The Road to 9/11, carefully and convincingly reviews decades of U.S. covert operations around the world, the questionable ties with allies and enemies alike, including terrorists; the administration’s ties to business; the secret policy decisions; and the hidden efforts to centralize power that led up to and influenced the invasion. The full details are dizzyingly complex and extend across the globe.

Only one example. He reviews U.S. covert policies under CIA Director William Casey and Vice President Bush at the time of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, in the 1980s, policies that continued and had effects later:

(1) to favor Islamist fundamentalists over native Sufi nationalists, (2) to sponsor an “Arab Afghan” foreign legion that from the outset hated the United States almost as much as the USSR, (3) to help them to exploit narcotics as a means to weaken the Soviet army, (4) to help expand the resistance campaign into an international jihadi movement, to attack the Soviet Union itself, and (5) to continue supplying the Islamists after the Soviet withdrawal, allowing them to make war on Afghan moderates.

Note also the view of business:

In 1997 the Wall Street Journal declared: “The Taliban are the players most capable of achieving peace. Moreover, they are crucial to secure the country as a prime transshipment route for the export of Central Asia’s vast oil, gas and other natural resources.”

That Rumsfeld’s behavior approached paranoia has been commonly discussed. I sketch my own interpretation for comparison. Scott develops the idea further in his theory of deep state politics.

The Report of the Constitution Project’s Task Force on Detainee Treatment has only recently been released and can be downloaded at http://detaineetaskforce.org/report/

Our support of Iraq in its war with Iran, in spite of its use of gas, is discussed in two New York Times articles:

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/18/world/officers-say-us-aided-iraq-in-war-despite-use-of-gas.html

http://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/15/world/us-says-it-monitored-iraqi-messages-on-gas.html

America stands against and will not tolerate torture. Bush’s full statement on United Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, 2004, can be found at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=72674

The Yale Genocide Studies Program reviews the abuses and genocide in the Congo Free State at http://www.cis.yale.edu/gsp/colonial/belgian_congo/

The death toll in Iraq has been tallied and analyzed at Iraq Body Count at http://www.iraqbodycount.org

That the intelligence gathered at Abu Ghraib and other detention centers was unreliable is reviewed extensively, with links to many sources, at http://thinkprogress.org/report/why-enhanced-interrogation-failed/

This Wikipedia page reviews fully, with many sources, why Saddam’s ties with Al-Qaeda were insubstantial: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saddam_Hussein_and_al-Qaeda_link_allegations

Philip Gourevitch and Errol Morris wrote a long piece on Sabrina Harman, “Exposure,” reviewing her behavior and reactions, in The New Yorker (March 24 2008), the source of the opening quotation.

Edited picture of Rumsfeld from The Huffington Post.

Picture of Sabrina Harman via The New York Times.

Man on a box picture via Wikipedia.

.

.

Gary Garvin, recently expelled from California, now lives in Portland, Oregon, where he writes and reflects on a thirty-year career teaching English. His short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel. His architectural models can be found at Under Construction. A catalog of his writing can be found at Fictions.

.

Map of a Utopia

Map of a Utopia

Photo credit: Leigh Backhouse

Photo credit: Leigh Backhouse