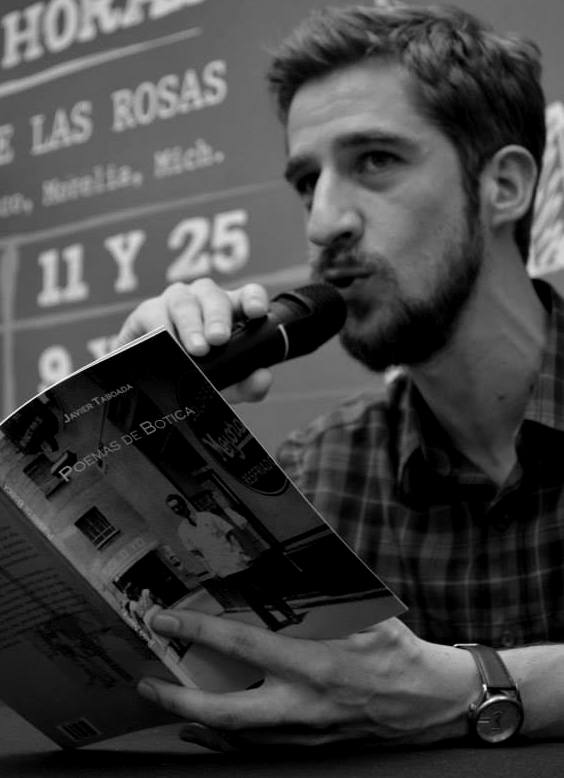

Gabriel Josipovici

Gabriel Josipovici

.

The first time I read Gabriel Josipovici, it was a slim, glossy brown volume sent to me by Carcanet that looked at first glance as if it might be poetry. It wasn’t, it was a short novel entitled Everything Passes, but I was struck by the amount of white space the reader is confronted with on each page, the writing being confined to a slender column of dialogue that is itself intermittent, fragmented by vertiginous silences. I began to read the first few words and felt myself slipping, slipping, as if down a polished chute, those aching blank spaces dragging me across to the next portion of dialogue as if across a dangerous precipice. I had to put it down for a while because it frightened me. And for the same reason I had to pick it up again. When it was finished, I was stunned. It was quite the most extraordinary piece of writing I had encountered in a long time.

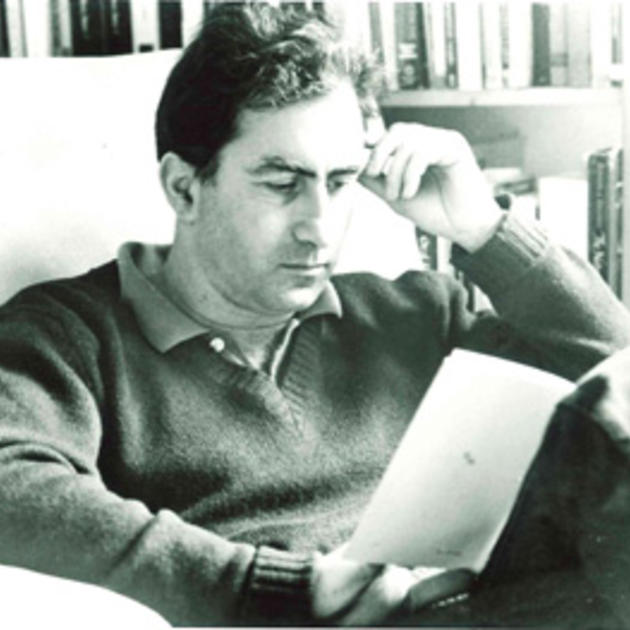

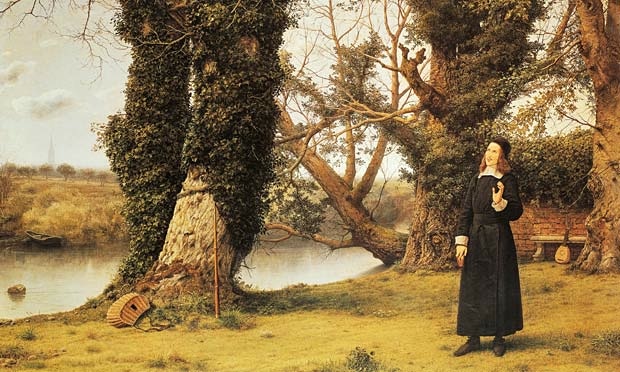

Why has Gabriel Josipovici never won the Man Booker Prize? Or the Goldsmith’s, or the Costa Book Award? It’s a common question among those of us who are thrilled by his work. His reception by the British critical establishment has been a rocky one over the past 45 years, which remains perplexing to me. A man who spent his career teaching literature, a published academic critic and a writer of novels, short stories and plays of striking originality, should surely tick the right boxes? Maybe there is an otherness about his writing that stems from his childhood in Egypt[1] that lingers in his books just sufficiently to disturb the mainstream mind? Maybe he has been too far ahead of his time, and only now are we able to catch up with him?

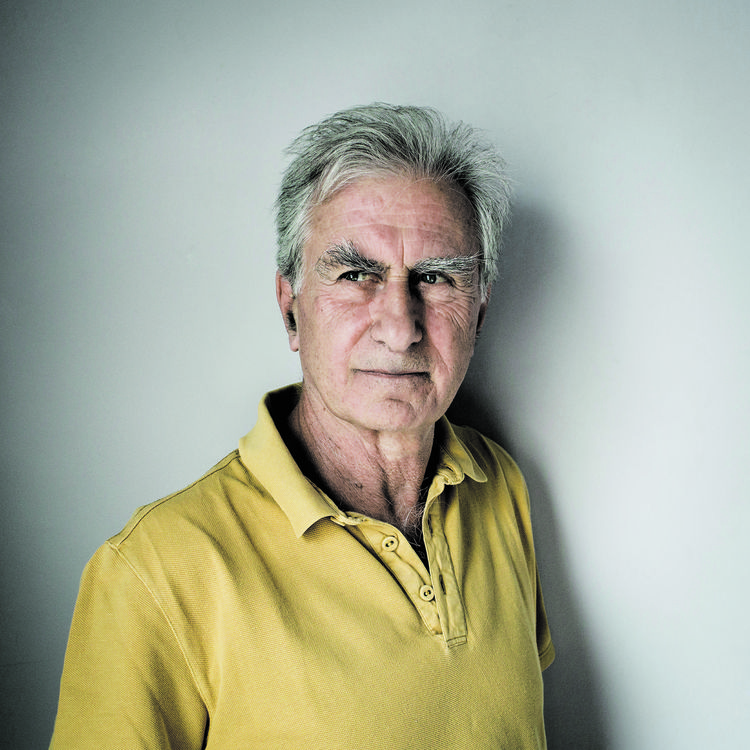

Over the past few weeks, Gabriel and I have put this interview together over email. During this period he celebrated his 75th birthday and a strong sense of retrospection grew out of our conversation, a chance to look at the entirety of his writing life. I told him our focus would be on creativity: his creativity, the creativity in his texts, the creativity that his writing draws out of the reader. This was the result.

§

Victoria Best (VB): Let’s begin with The Inventory, your first novel published in 1968. I’d like to get a clearer picture in my mind of your mid-twenties self, a literary critic by now but embarking on a work of fiction. What was the inspiration for this novel?

Gabriel Josipovici (GJ): I wrote The Inventory before I wrote The World and the Book (1966, 1965-70). I had been writing fiction at least since my early teens – Monika Fludernik, when she was researching for her book on my fiction and drama, came to the house to look through my files and unearthed a short story I’d published in the Victoria College school magazine in 1954 in Cairo, when I was thirteen. It concerned a road waiting for the road-mender who comes every day to work on a stretch of it and who doesn’t come that day and will in fact never come again because he’s dead. I read it with amazement, because though it was naïve and didn’t really know what it was doing it had the voice I associate with my later writing, showing that this ‘voice’ is something one is born with, or that is the product of one’s earliest years, and, however ‘formative’ the experiences of one’s teens and later life, it remains constant. I went on writing stories, and in the year I had off between school and university I tried to write a novel but it was so bad and I believed in it so little that I burned it. But a story I wrote then was kept for ages by Encounter, the leading cultural journal of the time, who eventually wrote to say that after long consideration they’d decided not to publish it, but they’d like to see anything else I wrote, which was encouraging. Then at Oxford I wrote and published stories in University magazines, and an enterprising publisher (now an agent), Gillon Aitken, got in touch and asked to see more of my work. I was tremendously excited, of course, but it turned out he only wanted a novel. I said I didn’t have one but would naturally send it to him if and when I did. Despite this, I couldn’t seem to write anything longer than short (very short) stories.

I have often spoken about how I came to write The Inventory. It was such a breakthrough for me and emerged out of such turmoil and anxiety that – I now realise – it has acquired in my mind something of the status of a founding myth. But I’ve recently been reading through some of my early working notebooks and I can perhaps take this opportunity to round the picture out a bit, to release it (for myself at any rate) from its mythic dimensions.

After two years as a graduate student at Oxford and two as a young assistant lecturer at the University of Sussex, writing short stories no-one wanted to publish, I was getting more and more frustrated, feeling the need to write something longer than a short story, partly because I desperately wanted to have something substantial to work on for months rather than weeks at a time, and partly because I felt that if I didn’t write a novel I couldn’t really consider myself a proper writer (I had not yet read Borges or Robert Walser, who might have made me think differently), and partly of course because, as Gillon Aitken had shown me, publishers weren’t interested in short stories from unknown authors. I had even got to the point of feeling that much as I loved my work at Sussex, I would have to give it up, since I didn’t want to spend the rest of my days living the comfortable life of an academic but feeling deep down that I had betrayed the most intimate part of myself out of laziness or fear or for some other unfathomable reason. But the trouble was that, as I’ve said, much as I wanted to write something extended I found myself totally incapable of doing so. For if I worked out a plot I found it so boring to flesh out that the whole business of writing suddenly seemed meaningless, while if I didn’t have a plot the impetus petered out after a few pages.

A word had come into my head: inventory. Simply repeating the word to myself gave me gooseflesh. I realised that this was because the word seemed to pull in two totally opposed directions at once: in the direction of unfettered subjectivity, invention, and in the direction of absolute objectivity, an inventory list. I discovered that they actually derived from two different Latin words, invenire and inventarium, but that didn’t matter, there they both were, nestling inside the single English word. And suddenly I had a subject I was excited about: someone has died and the family, with the help of a solicitor, is making an inventory of the objects he (it soon became obvious to me it had to be a he) has left behind. As they do so the objects lead them into recollection or perhaps even invention of the person they had known and of their relationship to him.

But though I elaborated my basic plot I could not get the novel going. There seemed to be an insuperable gap between what I sketched out in my notebooks and any actual novel I might write.

I had a term of paid leave coming up at the end of my third year of teaching, and all through that year I pushed myself to write The Inventory (I knew my title) and all through that year I found I just could not get started. The three months I would have to myself (officially to write a critical book) grew and grew in importance. This was going to be the crunch. If I failed here I knew I would have to leave academic life for good and I had absolutely no idea what sort of job I would be able to get to keep myself and my mother – all I knew was that it would be a good deal less enjoyable and satisfying than the job I had. So, once the summer arrived, I knew there were no longer any excuses.

A beloved cat of mine had recently died and I decided, to take my mind off my anxiety, to write a children’s story about him. I had no children of my own but I did know and like very much a colleague’s three little girls, who had been very fond of my cat. So I imagined myself telling them his ‘story’. Day after day I simply sat down and wrote what I heard myself telling them. He had been a large neutered Tom, already an adult when we had got him, and when he sat out in the garden contemplating the world he looked rather like a triangle with soft edges. I called the story Mr.Isosceles the King.

The advantage of a children’s story was that I had no great expectations of myself and so no inhibitions to be overcome. I also had a clear audience in mind. And so I found myself, day after day, while on holiday in Italy, writing about Mr.Isosceles, until one day it was finished and I realised I had a book there which I had had no idea I would write and certainly no idea of the form it would take a month or two previously. So, as summer turned to autumn and autumn to winter, I had a new sense of confidence that just sitting and writing for a few hours every morning would yield something. Yet that did not allay my mounting sense of panic. I would wake up every morning drenched in sweat, my heart pounding. I knew it really was now or never. But fear, I discovered, can be a very useful thing. It can push one past all the inhibitions that have been holding one back and get one across that seemingly insurmountable barrier between notebook and novel.

VB: You’d already discovered the Modernist writers you loved and your relationship to them as a critic is clear. But what was your relationship to Modernism as a fledgling artist at this point? What did you hope to explore or elaborate in creative writing?

GB: The answer to the second question is: nothing. One writes because one has to, not to explore or elaborate anything. The answer to the first is, I suppose, that I had read Proust and Mann and Kafka, and Mann had made me understand that our modern situation is different from anything that has gone before, and fraught with difficulty; Kafka had made me understand that I was not alone in my sense of not belonging anywhere or having any tradition to call on; and Proust had given me the confidence to fail, had driven home to me the lesson that if you come up against a brick wall perhaps the way forward is to incorporate the wall and your effort to scale it into the work. I had read Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras, and been excited by the way they reinvented the form of the novel to suit their purposes – everything is possible, they seemed to say. But when you start to write all that falls away. You are alone with the page and your violent urges, urges, which no amount of reading will teach you how to channel. ‘Zey srew me in ze vater and I had to svim,’ as Schoenberg is reported to have said. That is why I so hate creative writing courses – they teach you how to avoid brick walls, but I think hitting them allows you to discover what you and only you want to/can/must say. Not always of course. The artistic life is full of frustrations and failures as well as breakthroughs. You are alone. No-one can help you. I think that’s what Picasso means when he says that for Veronese it was simple: you mapped out the territory, started at one corner and worked forward. But for us, he says, the first brushstroke is also the last.

So: to go back to the genesis of The Inventory. I had my first scene in my head: the solicitor arrives at the house and meets the family of the deceased. I could visualise the street and the house. But how to put that down in words? Now I was sitting at the desk determined to write the book rather than simply thinking about it, this suddenly became a crucial issue. Did I use one sentence, one paragraph or one page to describe the scene? As I scribbled I found myself rejecting one effort after another: they were not in my voice, not what I wanted. They were in all the voices of all the novels I had ever read. How then to find how I wanted to say it? And suddenly, under pressure, the breakthrough occurred. I realised I was not interested in describing the scene, what I wanted was to get the characters talking to each other, to get the thing under way. And it came to me that I could simply drop all description and find ways of conveying the scene entirely through dialogue. With that the book became a challenge and a pleasure instead of a dutiful chore. I had my lists of possessions, my inventory, and I had my characters, and that was all I needed.

Years later I read Stravinsky’s account of a similar breakthrough he had experienced as a young composer (it was when working on Petrushka I think): ‘It was as though I had suddenly been given an extra joint in my fingers,’ he said. And years after too that I began to understand why I was so resistant to description, and why dialogue on the contrary seemed exciting. It was not description as such that I felt I simply could not (my body would not) do; it was that I could not countenance the introduction of an impersonal narrator who would be able to describe the scene from a privileged position outside space and time. It might seem that a first person narrator would solve the problem, but unless he was a sort of Tristram Shandy (and I found that much as I loved that book its wonderful playfulness was not something I was drawn to emulate) there would be exactly the same problem: in life things slip past us, we are always in the midst of them, we do not stop and describe, we simply take in our environment as we go. The traditional novel pretends to be doing that but in fact the first person narrator, when there is one, stands free of such pressures and simply tells the story. The descriptions he or she provides are meant to orient the reader, to act like stage directions. But I did not want such dead wood in my book. I wanted it to be alive from start to finish, from the first word to the last. And in dialogue it could be alive, for what dialogue did was provide words where (in the fiction) the characters would be providing words. Why the words are spoken, how speaking them affects the situation and what they ‘mean’ can be left as open as in any encounter in real life.

That was how, much later, I came to explain my peculiar aversion to description and my recourse, here and later, to dialogue. At the time I merely felt that I was embarked on an exciting journey and it was up to me to keep going till I got to the end.

VB: I’m also intrigued by your use of repetition – very strong in The Inventory, but also to be found in many other of your works. What is it about repetition, do you think, that brings us closer to the real?

GJ:I discovered, as I worked, that I could do without transitions. I could simply juxtapose fragments of dialogue and build up a rhythm in that way. Repetition was part of that process. As I soon discovered, Stravinsky worked in rather the same way. Instead of the development so central to the Western classical tradition he worked with small cells which he juxtaposed with others or transformed by various processes. And his descendants, I realised, were living and working in here England – Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle, then young radicals setting out on their own paths, influenced by Stravinsky as well as by Varèse and Messiaen, but also harking back to late medieval and early Renaissance ways of building large works by other means than classical development. I spent many exciting hours at the concerts of the Pierrot Players, the Fires of London and the London Sinfonietta. And in the course of that discovered Stockhausen, Berio and Ligeti, very different composers, but all rejecting the linear, developmental processes of classical music and finding their inspiration in the musics of the Middle Ages, India and the Far East. It was an exciting time.

VB: What did the experience of writing this first novel teach you?

GJ: One other thing I discovered on the way was that under pressure of the situation all sorts of unexpected things occur. A writer I had not really thought about much, Raymond Queneau, became a great source of strength as I struggled with the book. Recalling his ability to maintain wild flights of fancy and yet hold on to ‘the real world’ of the France he knew, particularly in Zazie dans le métro, gave me the confidence to let go in ways I had never been able to do in my short fiction. It was frightening but exhilarating, a roller-coaster ride with no assurance that I would land on my feet at the other end. But, somehow, I did (I learned that if you let go you often do).

Raymond Queneau

Raymond Queneau

VB: How was it received?

GJ: Respectfully. I think it was possible to read it as a version of the English realist novel. And those were perhaps more open times, in the late sixties. Iris Murdoch’s first novel, Under the Net, was, after all, dedicated to Queneau and this was the time when John Berger and David Drew, Europeans to their core, were writing in the back pages of the weeklies. Critics only turned against me with my fourth novel, Migrations, which was a break from the predominantly dialogue novels I had been writing till that point.

VB: As a critic, how would you define the role of the reader?

GJ: I’ve no idea. Perhaps we should drop such notions as ‘the role of the reader’. Reading, as you know, is the most natural of activities. I’ve seen children who can’t yet read grab the book from their father’s hand and sit there, imitating him, turning the pages, willing themselves to read, as it were. I was fortunate to grow up in a pre-television and pre-computer age, so that there was nothing else to do if you were on your own except kick a ball around or draw or read. There came a moment when my mother put down the book she was reading to me to go and do something and I picked it up and went on with it. She came back and I handed the book to her to continue, but she only smiled and said she was busy and perhaps I could go on on my own. And of course I did. I wanted to find out what happened next. And I remember lying by the pool in the sports club in Maadi, near to Cairo, where I grew up, and looking up at the big clock on the wall and thinking: soon it’ll be time for lunch and after that I can go on with my book. And I felt a tingling in my whole body at the thought. I think the book in question was Enid Blyton’s The Castle of Adventure – I’ve never read anything more thrilling, though I’ve had many similar moments of looking forward to a blissful evening with a book I was absorbed in.

VB: I ask this because Migrations is an exemplary novel in the singular effect it has on me as a reader. Your narratives have such extraordinary elasticity; they open up new spaces in my mind. I find myself drawn to the trope of migration itself, and the way your characters often walk and talk, or walk and think; their movement echoes the mental travel I undertake reading you. Do you have such a figure as Iser’s ‘ideal reader’ in your own mind when you are writing? What do you think your novels ask of the reader?

GJ: I think one writes the books one would like to read but that no-one has written. So as you write you write for yourself as reader. That figure is not in your mind so much as in your body. He is not ideal at all, he is this person: you as reader of books.

But the first part of your question deserves a fuller answer. Quite a few years ago now I received a letter from a reader of my work who told me she had had M.E. [Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, the name previously used for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, though some argue the two illnesses are different] for many years, and for a long time no doctor would take her seriously, though she had fought hard to get her condition recognised (as of course it now is). She said reading my work had a physical effect on her, actually did what medicine and therapy could not do, that while she was reading my work she started to move better, to feel more like her old self. We corresponded and it turned out she was actually in a wheelchair, but clearly a very determined lady (in earlier life, she told me, when the disease was less virulent, she had acted and even taken a small company on a tour of Africa). She asked me if I thought she should do a PhD on my work, and tried to get in to various universities to do that, but for one reason or another it didn’t work out. I suggested to her that PhDs were probably not a good idea in the Humanities (a view I hold generally), and that if she felt driven to write about my work she should just do so. Over the course of the next years she did that and in the end had a substantial book. I read it with interest because I had always been fascinated by the kind of thing Oliver Sacks was doing and loved the idea that books could have a physically, not just emotionally or intellectually, restorative effect on the reader, not just on the writer. I had hoped that in the wake of Sacks’s popularity a publisher might be persuaded to publish her book, but alas no-one would and I remain one of its sole readers. But I cherish my copy as a witness to the effect art can have.

I don’t think there’s anything uniquely ‘restorative’ about my work; if she had happened to read someone else I’m sure that would also have done the trick. Not anyone else, but I have certainly found that the authors I warm to affect my body and not just my mind. And in essays and books like Writing and the Body I’ve tried to explore in an amateur way why that should be the case. But while neurologists have been (rightly) alert to the therapeutic effects of music, and even painting, poetry and fiction have not in the past been examined from the same perspective. This has, though, recently become a topic of research, and Terence Cave, for example, has devoted some of the money he received from his Balzan prize to setting up a team in Norway to look into it, while Paul Davis and a team at Liverpool are engaged in the same enterprise. Both of them though seem to me overly scientific and abstracting. I just wish the topic would find its Oliver Sacks.

As for Migrations and migration, that work was indeed another breakthrough for me. I had grown to feel that the dialogue form I had developed in The Inventory and which I had adopted for my next two novels, Words and The Present, was no longer satisfying. I had had a few plays publicly performed and been made welcome in the wonderful BBC Third Programme and the Radio Drama department, presided over by Martin Esslin, and full of great producers able to call on the best actors in the land. My play Playback, which I worked on with that great producer, Guy Vaesen, kicked off a season of radio plays exploring the possibilities of the form. I felt more at ease in my teaching role at Sussex now it was established that part of my time at least would be spent writing. Yet in personal terms 1972-5 were very difficult years for me. A good friend committed suicide. My beloved collie dog, who had developed epilepsy in a very violent form, grand mal rather than petit mal, with fits lasting all of 36 hours, had finally had to be put down, and I could not get out of my head the look in his eyes as he felt a fit coming upon him and with no idea, of course, as a human being would have, of what was about to engulf him. I had behaved very badly to a number of people who were very close to me. All I wanted to do was beat my head against the wall and scream. In those circumstances the lightness and humour of my early novels did not seem to be of any help. I wanted to be engaged in something that went deep and that (as I put it to myself) wound round and round and round, and in the writing of which somehow the shackles I felt were binding me tight might get released. I felt I needed to go down into my own life, but when I did so I found I had no ground to build on – I had no maternal country to dream about, not even a maternal language. I felt I was a sort of absolute migrant – someone on the move from my birth on, with no place to return to and no place to go to. How, in that condition, to find any solid base on which to stand to build something substantial? Yet as I thought about all this I began to wonder if perhaps my condition was more typical of the human condition at large than our culture (any culture?) was willing to recognise. Most people have a patria and a maternal language and the notion that these are primal is somehow unquestionable. But is it true? Or is it perhaps just another myth. Perhaps if one dug down deep enough one would find only shifting sands. I started to read quite a lot of French psychoanalysis (my close friend John Mepham was a great resource there), and in particular André Green. And I began to feel that perhaps I could find a fictional form for all this.

Two images came into my mind under the pressure of trying to find my form: a Francis Bacon image of a man vomiting into a lavatory, bent double over it, a painting I must have recently seen; and Epstein’s great sculpture of Lazarus rising, the shrouds that had been wrapped about his body starting to come loose, which I had discovered in New College chapel when I was a student down the road at St.Edmund Hall and which I often used to go and contemplate in my time at Oxford. I was also listening to the current work of Peter Maxwell Davies, those enormously slow, enormously long works audiences at the time were walking out of, like Worldes Blis and the Second Fantasia on John Taverner’s In Nomine, which developed almost imperceptibly, like their great late medieval models, from tiny cells to monumental structures. And then I heard Harrison Birtwistle’s The Triumph of Time, and I knew I had to write my book. It knocked me backwards, that long long slow ritual on strings and percussion, punctuated by the piercing, beautiful descant of the clarinet. Towards the end of the huge single movement there is a glimpse of something found, then that too is swallowed up in the funereal march. Finally, I was just starting to learn biblical Hebrew in order to read the Hebrew Bible in the original language. I was also reading the Bible in English quite intensively. I came across this phrase in the prophet Micah: ‘Arise and go, for this is not your rest.’ (Micah 2.10) I loved the sound of it in Hebrew: c’mu velochu ki lo zot ha-menuchah, and I was excited to discover that the word for rest, menuchah, is also to be found in various other places in the Bible, notably when the dove is sent out of the ark by Noah but can find no rest for her feet because the earth is still covered by water. I knew then that I had found the epigraph to my book, and, after much internal debate, decided to leave it in Hebrew to give a sense of its otherness and strangeness, and since the precise reference would allow anyone interested to look it up in an English Bible.

I had been driving up and down the road that leads from Brixton to New Cross, a road that filled me with horror every time I took it, it was so endless, so run down and desperate (it must have changed dramatically, like all of London, in the forty years since I was there), and I took that as my location. I hoped that by facing that despair and the despair of the man in Bacon’s sealed room vomiting into the lavatory, by finding a way of writing it, I might regain a modicum of balance. But I was terrified that so instinctive a procedure would lead to nothing more than a mess, so that though I wrote it straight, day after day, never looking back, once that first draft was done I subjected it to more analysis and drew more grids than I have ever done before or ever want to do again. I found that the pattern 9+1 was a recurrent one, tweaked it here and there, and decided on a title with nine letters plus the sign for the plural. And so Migrations was completed.

I had been so deeply immersed in it, and it had seen me through such a bad time, that, once my only reliable reader (relied upon to criticise as well as praise, which is essential), my mother, had read it and said she was deeply moved, I felt happy to send it to Gollancz, who had published my previous three books, including my first volume of short stories, Mobius the Stripper: Stories and Short Plays. That volume had been awarded the Somerset Maugham Prize, a wonderful accolade for a young writer, news I had received on returning from a brief holiday to try and come to terms with my friend’s suicide, but at the last minute the prize was withdrawn on a technicality (I had not had an English passport when I was born, a fact I had never tried to hide, but which it seemed was a stipulation by Maugham for the award of the prize, even though in his lifetime he had waived that requirement in a couple of instances, and which the publishers, who submitted the book, had overlooked) and Gollancz, who had slipped bright yellow wrappers announcing the award on all copies of The Present, which they were about to publish, had to hurriedly remove these. Insult was added to injury when the chair of the Society of Authors, which managed the prize, Antonia Fraser, wrote more or less accusing me of deliberate fraud and ended with the chilling words: ‘However, I am sure you will agree that the publicity you are getting more than makes up for the withdrawal of the prize.’ Be that as it may, Gollancz took one look at Migrations and turned it down. When it was eventually published it was rubbished by the critics, Susan Hill, for example, saying (was it in The Observer?) ‘If you like that sort of thing then that is the sort of thing you will like.’ It was my first encounter with the entrenched conservatism of the English media and especially of established English writers, a conservatism I now suspect (after the similar outburst of bile that greeted my recent critical book, What Ever Happened to Modernism?) is due more to anxiety than to anything else.

VB: The other figure that recurs across your works is the figure of the man alone in his room. This makes me think of both the reader and the writer, who are often in such a situation. What draws you to this figure, or perhaps better to ask, how was this figure thrust upon you?

GJ: I think I’ve answered this in relation to Migrations. As for its larger or deeper significance, all I can say is that my pulse quickens when I see paintings or listen to music or read books where the constraints are fairly tight – where a room hems in the figures, as in Vermeer or Hammershøi or some of Giacometti, or the musical resources are limited, as in Renard and Histoire du soldat. Why it should do so is a difficult question, better left to others.

VB: I wonder if we might bring in your notion of art-as-toy here; something material and real in its own right but invested with imagination and fantasy. Do you think, as both author and critic, that the ‘toy’ of art is different – invites different kinds of play – for its creator than for its consumer?

GJ: Not sure I understand this. Art is making, poiesis, and what I like about much modern art is that it acknowledges this, indeed, makes a virtue out of it. We may be nostalgic for the organic, for art growing as a tree grows, but to accept that art is made by someone at some moment is exhilarating for me. That’s why I love Tristram Shandy. Of course there are dangers. If one starts to think of it as simply artificial one is set firmly on the conceptual route, and though I am interested in Duchamp, who was a complicated and conflicted figure, I am not much interested in his followers. A key moment in What Ever Happened to Modernism?, to my mind, though no-one has mentioned it, is the confrontation I set up between Duchamp and Bacon. Both of them want nothing to do with mere description, nor do they want to go down the road of abstraction, but where Duchamp views every artistic gesture with suspicion, Bacon is prepared to trust the moment, to trust his painterly gesture. Duchamp has all the philosophical answers, but Bacon is a bit like Dr.Johnson confronting Bishop Berkeley: he kicks the stone. Duchamp will never be accused of self-indulgence or losing the plot, but my heart is with Bacon. And more than my heart. I believe that if we realise that a child lives the toy, lives with the toy, while never for a moment thinking it is anything other than a toy, then we perhaps have a better model of our relationship to art than the conceptual one. I at any rate dream of making a work that is like some complicated toy you can dismantle and put together again and that is always not just more than the sum of its parts but in a different dimension. So I love works like Perec’s La vie mode d’emploi or Birtwistle’s Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum and Steve Reich’s percussion pieces – but of course I also love works which are not like that at all, such as those of Kafka and Beckett and Stockhausen and Kurtág.

VB: Perhaps we might address the influence of Jewish elements in your works. It would be foolishly reductive to call you a ‘Jewish writer’; yet patterns of migration and exile are evocative, and many of your protagonists identify themselves as Jews (in a way that is often serious and amusing at once). How would you describe these elements in your writing?

GJ: Until well into my thirties I knew I was Jewish, knew my mother and I had survived in France during the war more by luck than anything else, yet I had no connection with things Jewish. My first books were written by someone without any contact with organised religion or with any religious tradition. So I was intrigued when, years later, a German colleague at Sussex, who was working on the way in which the Nazis took over the flats of Jews in Vienna after the Anschluss, told me she felt The Inventory was a very Jewish work: ‘It’s a book about the fragile remains of one person’, she said, ‘and the memory of that person in the objects he leaves behind and in the lives of those who survive. Surely you were obliquely writing about the war?’ I assured her that that was not the case, but of course accepted that sometimes we write more than we know.

Then, as I have said, at the time of writing Migrations I was starting to read the Hebrew Bible intensively. And what I found in the narratives there was a kind of writing that I had only come across in the work of Marguerite Duras: narratives denuded of description or psychologising, narratives which draw their power from the way dialogue and the stark description of ‘what happens’ hint at depths which evade even the speakers themselves. It was very exciting. And at the time too I became friends with a number of wonderfully thoughtful and interesting religious Jews, mainly Reform, Francis Landy, Geoff Newman, Jonathan Magonet. I found they shared one of the central attitudes I had been delighted to find at Sussex when I joined the University, a belief that one need not always have the answers, that sometimes genuine puzzlement is more fruitful than clear solutions. I admire and respect their devotion but because I never had any religious education or went to synagogue as a child I feel a little bit outside it all, but they – and they are still good friends – seem to accept me as I am. And like them too I despair of what is happening in and to Israel. The Jewishness I cherish is the one that stresses wandering as the human condition, not any sort of possession of a promised land.

So I would say that the feeling that I am Jewish is now more informed than it was, but it remains, like my awareness of Proust and Kafka, a support and a comfort rather than anything else.

VB: When I put down one of your novels, I feel that something significant and real has happened, and maybe it’s a case of Eliot’s belief that ‘mankind cannot take too much reality?’

GJ: Naturally I’m delighted you feel that way about my books. I suppose what I discovered in writing The Inventory is that I want a work to live its own life from the first word to the last. With the first word something unusual is happening, something for which there is no justification, which is a cheat, and yet which is also magical, wonder-full. I want to celebrate that, embrace it, not deny it, as do most works of fiction. I’m not interested in telling a story. I love the narratives of the Hebrew Bible and the narratives of the Border Ballads and of the Grimm tales, but most so-called classical novels turn me off – I don’t want to be filled with Stendahl’s or George Eliot’s inventions, or even Tolstoy’s, all those descriptions of clothes and rooms and the rest – I want books that leave a space for me to discover myself, like Proust’s or Kafka’s, or that get my body dancing, like those of Queneau and Muriel Spark. Lots happens in Balzac and Dickens, but I’d rather read Chandler or Wodehouse, writers who know that what they are doing is neither ‘significant’ nor ‘real’. But that’s no criticism of the classic novel (or the contemporary Goncourt or Booker contender), just that it’s not for me. As Stravinsky said of Mahler: ‘Our pulses beat at different rates.’

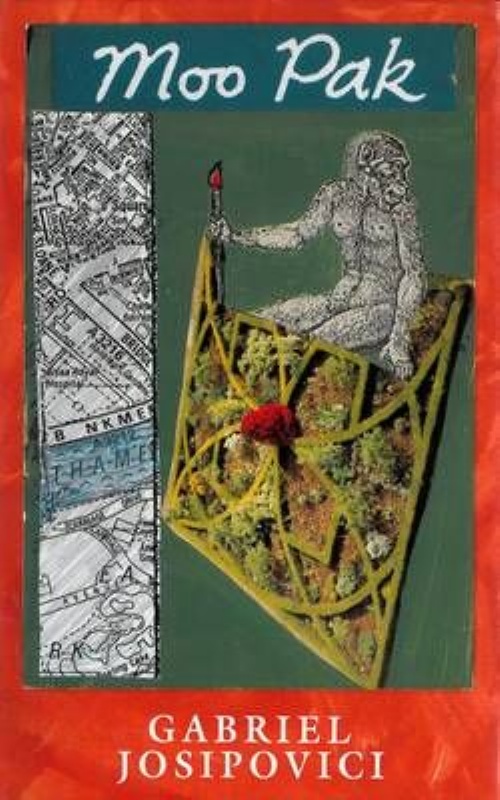

VB: And yet, I’m not sure I’ve read anything in which you abandon full characters. I’m thinking now particularly of the monologue novels like Moo Pak and Infinity, where you have Jack Toledano and Tancredo Pavone vividly depicted by their friends and servants, Damien Anderson and Massimo, who frame their stories. Wodehouse gives his characters easy, ridiculous, robust emotions, but what touches me about these two novels in particular is the love, friendship and loyalty, the very real emotions that drive the narrative. Friendship, suffering, the drive to create; I feel your works are very rich in emotion ‒ but entirely empty of sentiment. Would that be fair to say?

GJ: I’ve always felt that while a short story can spring out of an idea or a phrase a novel has to have characters I can empathise with. You have to have something genuinely invested in it if you are to spend a year or three of your life with a piece of fiction – there has to be something you want to explore and something you are moved by. For a long time I worked with the initial conceit of Infinity, and with the figure of the eccentric avant-garde Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi, but it was only when I opened myself to the human dimension of the relationship between Pavone and Massimo that the novel finally came. On the other hand I always conceived of Moo Pak as a dialogue novel with one part of the dialogue missing. ‘Rich in emotion but empty of sentiment’ – I can’t think of a nicer description of my work or one I would be happier with.

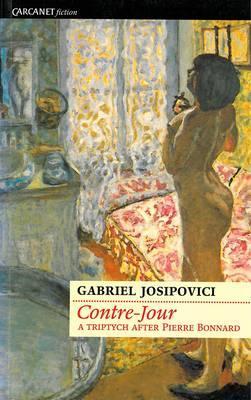

VB: I’m also very intrigued by the ghosts of real people behind some of your novels – Giacinto Scelsi in Infinity, Pierre Bonnard in Contre-Jour, Joseph Cornell in Hotel Andromeda. I don’t for one second think this is a biographical urge, so what do these real figures offer you in terms of inspiration or structure or… maybe something else entirely?

GJ: I too have been intrigued by that question ‒ ever since I worked on The Air We Breathe, behind which lies the figure of Claude Monet, and which was sparked off by my looking at a book of photographs of the aged Monet and his wife – sitting on the beach in Dieppe, pottering about the garden in Giverny, etc. – and then found myself following it up with a book loosely based on the life and work of Pierre Bonnard, Contre-Jour. Enough, I said to myself, or people will start thinking of you as a novelist who only writes oblique biographies of painters. And then I found myself writing a book at the centre of which was Marcel Duchamp, The Big Glass, and fifteen years later a book in which Joseph Cornell figured prominently, Hotel Andromeda. It’s true that in between I wrote a number of novels – Now, Only Joking, After, Making Mistakes – which do not have an artist at the centre, but even so, what was going on? All I can say is that something in the life of this or that artist does more than intrigue me, it grabs me to such an extent that I cannot rest till I have had a go at discovering why, and doing so in the only way I know, by writing a piece of fiction. With Bonnard it was hearing a talk about why he painted his wife Marthe so frequently lying stretched out in the bath (because, said the speaker, she was a compulsive washer); with Duchamp it was reading about how, when he learned that the work on which he had spent so much time and energy, The Large Glass, had been damaged in transit to an exhibition, the glass panels cracked beyond repair, his response was: ‘Wonderful!’ With Scelsi it was reading the crazy remarks he made to interviewers and some of which were printed in the sleeve-notes to his CDs (‘I was born in Mesopotamia 2800 years ago’; ‘Other composers like to hold up their profiles to the photographers and to show off their noses; I have a finer nose, a perfect Roman nose, much finer than any of them but I have never let myself be photographed.’). With Cornell it was seeing those photos of him in old age in his garden or his study in the house in Utopia Parkway he had lived in most of his life, looking like a figure already passed over to the other side. But in every case I had to love the art or at least to find it highly interesting. I could not spend a year or more of my life with someone with whom I was not in some sort of sympathy.

And I think too that the combination of work that I found fascinating and a life that intrigued me and which I could identify with acted a bit like the double focus of that word ‘inventory’ with my first novel – it gave me the rudiments of a plot, and a form. Already in some very early stories I had found myself trying to find literary equivalents of paintings by Picasso, Vermeer, Dix, and others, and taking as the ‘content’ of the story what the painting represented: two large women running on a beach, a woman at the harpsichord, a mirrored room in Brussels during World War I. So it’s clearly more than a passing fad.

VB: I am particularly interested in the depiction of creativity that comes out of your work. There seems to me to be one constant feature uniting the artists in your pages and that is their absolute dedication to art. What makes this something you want to write about?

But I am also curious about the way that these characters suffer ‒ or make those around them suffer ‒ for creativity. Do you think that creativity is necessarily costly; that it always demands a measure of sanity or love or peace of mind to be paid?

GJ: That, I suspect, is the deeper reason for my fascination with these artists. Artists are the saints of our day, no? Surely, they argue by their choices, life is in the end about something other than money and status, life is a quest, a puzzle and a gift. On the other hand there is something ridiculous about this stance. Something quixotic. For already in the early seventeenth century Cervantes sensed that the dedicated life was an absurdity, whether that life was passed in dedication to God or to knight errantry or to the writing of books. I think that is one reason why I write novels and not critical books about Bonnard, Duchamp etc. Because fiction can show up the absurdity, even the self-delusion (Infinity), or the costs to others (Contre-Jour) of the obsessive artistic life, as well as its wonder and glory. That’s the beauty of art, of fiction, that it can accept and reveal complexity, even contradiction, and leave you simply pondering how life is.

VB: On that note of costly creativity, maybe we can return to you in the 80s and 90s. You’d been a young man longing to create works of literary fiction and here you are doing so, an established author. Had the experience been as you expected it would be? How had it changed you (if indeed it had)?

GJ: I’m not sure about ‘established’. After the débacle of the Somerset Maugham Prize and Migrations (1977) I had been labeled an ‘experimental’ writer once and for all and routinely abused and dismissed in reviews or else ignored altogether. With each new book of course I thought: This time they’ll get it, this time they’re bound to see what I’m after, but it didn’t happen. Publishers would take one book, swear they were in it for the long haul, then drop me when no-one bought the book, until I finally found a home in Michael Schmidt’s then expanding Carcanet fiction list. Carcanet have stood by me for the past thirty plus years, though during that time their fiction list has had to shrink and almost disappear (I think I am the last remnant of a once-vibrant list that included Clarice Lispector, Natalia Ginsberg, Leonardo Sciascia and Christine Brooke-Rose). When Contre-Jour was taken by Gallimard I thought: at last I will find a public to appreciate me. But Gallimard pushed it as a novel just about Bonnard and it fell flat and they lost interest. It wasn’t till the late nineties that a Swiss publisher, Gerd Haffmans Verlag, began to take my work and to publish it in Germany that I felt I had found a public. It wasn’t just that reviewers were kinder to the work, it was that the reviews were intellectually on a different level to the English ones and engaged with the work (Haffmans Verlag brought out Now, Contre–Jour and Only Joking when that book had not even found an English publisher) in ways inconceivable to English editors and reviewers. When I gave readings from my work in Germany I found people responding to it on its own terms, instead of more or less asking me to justify myself, as I felt on the rare occasions I had done readings or interviews in England. But then Haffmans went bankrupt, a seemingly common fate with any press that took me on. Finally in the new century dedicated small presses in France (Quidam) and Spain (Raig Verde, Complices) began to bring out my books in those countries, and first Zweitausendeins and then Suhrkamp and Jung & Jung in Germany. But it’s really only in the last few years (with the rise of the internet and blogs like yours and Steve Mitchelmore’s) that I’ve ceased to feel I’m there on sufferance and the sooner I disappear the happier the literary establishment will be.

Of course all that has its good as well as its bad side. I remember my Oxford friend, the composer Gordon Crosse, saying to me all those years ago: ‘For the artist there are two dangers, success and failure.’ Wise words. I’ve seen what success has done even to writers I admired (Golding and Pinter for example, even Claude Simon) and felt in a way glad it had never come my way. Failure – it depends how you define it. When all public responses are not just negative but dismissive it’s sometimes hard to keep going. We are not Buddhists, we need some sense that what we are doing is more than self-indulgence. But of course in the end we go on writing because we have to/want to. (David Plante once said to me: ‘Remember, Gabriel, no-one asked you to do this.’ More wise words.) I have now accepted that I will always only appeal to a very small section of readers, anyway in this country, but probably everywhere, but I have also come to feel in the last few years (not in the eighties and nineties) that there is a growing body of people for whom my writing really matters, and that is heart-warming and encourages me to keep going.

VB: You have written the most moving tribute to your mother, the translator Sacha Rabinovitch, in A Life, the memoir of your relationship. What do you think she gave you as an artist?

GJ: It’s so difficult to say. She gave me life, of course, and then she saved us both when we were stranded in France during the war. When I was fifteen she once again showed courage and determination when we left Egypt for good in 1956, just before the Suez crisis. She left her sister, her only remaining family apart from me, her beloved dogs and all her possessions to face a totally unknown future. She had no idea if she would be allowed into England, where I was going to finish my schooling, and, if not, what would happen to her. So my being in England and becoming an English-language writer I also owe to her forethought and determination.

All that might have been a heavy burden for me to bear, but she was also the most generous and the most loving of people, and gave me all her love without (I think) spoiling me – a difficult balance. But the real miracle was that as I became an adult (in fact from the moment I came back from Oxford, where I had been on my own for three years, for the first time in my life) we found we had a great many shared interests ‒ and even tastes – in books, in music, in art, animals, in walking – and became firm friends. Which doesn’t mean of course that we did not have quarrels, sometimes terrible ones, when people are that close it’s probably inevitable. But it was wonderful to have a friend in her to whom I knew I could always turn. When I began to write she was naturally the first person to whom I showed my work. And she was invariably encouraging though quite ready to make critical comments when she thought they were justified. Her response to The Inventory was typical. When a draft of that book was finally finished I left it with her to read and went off to London for the day. When I entered the house on my return my heart was beating. I felt that this was the moment of truth. I had no idea if what I had done was very good, quite good, or just plain rubbish. Her first words were: ‘It’s wonderful.’ And as the sense of relief flooded through my body she added: ‘I think you’ll have to work on the ending, though.’

So I suppose in answer to your question I have to say: she gave me everything. The deep confidence of knowing that, however out of step I was with the prevalent culture of the time, someone else thought the work good, someone I could trust. I would not have written what I have had it not been for her, and one of the hardest things about her death was losing my best and most reliable critic.

VB: Let’s talk about Goldberg: Variations, which strikes me as your most widely-reviewed novel to date. I also find it quite different to everything else you’ve written without being able to put my finger on why that should be so. It is such a unique piece of fiction – how did it come into being?

GJ: I think it was in the early nineties that I came across that anecdote about Bach’s writing of the Goldberg Variations. It derives from Forkel, Bach’s first biographer, but I can’t remember if I had been reading Forkel or another book on Bach or perhaps it was just a passing mention of the story in something on quite a different topic. (Scholars, it is worth saying, now cast doubt on every aspect of the anecdote.) It seems that Count Keyserlingk, a Leipzig nobleman, had insomnia, and he asked his court musician, the harpsichordist Johann Gottlieb Goldberg to play to him at nights in the hope that that might send him to sleep. Goldberg in turn asked Bach to write him a suitable piece, and that was how one of the greatest works of music ever written came into being. I thought it would be fun, as a sort of homage to Bach, to see what happened when I transposed the story to Britain and turned Bach from a composer to a writer. And I conceived the idea of an English nobleman in the late eighteenth century developing a debilitating insomnia and calling up his not too distant neighbour, the renowned writer of German-Jewish descent, Samuel Goldberg, to come and read to him, and then to insist that he read something he had written that day. It was an amusing jeux-d’esprit, and I got it written without too much difficulty. As I was finishing it I heard Judith Weir, a composer I knew slightly, talking on the radio about the importance to her and to so many modern composers, of Bach. I decided to send her the story, something I regretted doing for the next few years, because she wrote back quite soon to say she had much enjoyed reading it on a train journey to Manchester and when would I have the other twenty-nine variations to show her?

Of course once the seed has been sown in your mind it’s impossible to dislodge. I loved the Variations and every time I heard them I was deeply moved by the fact that when the Aria with which it starts returns, unchanged, at the end, we hear it completely differently, because of the long road we have travelled. I also loved the idea of a piece that would be made up of a number of discrete yet interlinked parts and that would yet be more than the sum of its parts. But I had set my initial ‘variation’ in England in the late eighteenth century, and while it was possible (for me) to write a piece of historical fiction that covered twenty pages I was not sure I could – or would want to – keep it up over a whole novel. I am not a historical novelist and am not interested in historical novels. Certainly not in twentieth century ones. Nevertheless, I thought I ought to give it a go. After all, I greatly admired William Golding’s The Spire, set in the Middle Ages, admired it particularly for the fact that Golding made the setting feel completely authentic yet hardly went out of his way to ‘set’ his novel in a bygone time. Perhaps I could learn from him.

Over the next few years I struggled with the project, periodically growing sick of it and turning to other things, yet always coming back to it. I couldn’t get it off the ground and I couldn’t quite let it go. I cursed Judith Weir. But in the end I had to let it go. I had written half a dozen ‘variations’ and roughed out the end, but it seemed terribly false and arch to me and I dropped it. I turned to contemporary subjects with relief and wrote Moo Pak and then Now, both set in present-day London. But after my mother’s death and the emotional turmoil that followed, I found myself spending more and more time in Berlin where a friend had a flat and a bicycle to lend me, and perhaps it was the distance and the unfamiliarity of my surroundings, but I found myself turning to my abandoned novel again. As I cycled along the canal or river towpath in Berlin, stopping off at beer houses with shady gardens, I pondered the problems of my book and found myself starting to work at it again. I realised that perhaps what I should do was punch a window into the present in the fabric of the building I had erected, so to speak, and let the later ‘variations’ enter the modern world. And then other things began to fall into place. I had decided from the start that I would not follow Bach’s variations slavishly, writing a very fast or a heavily ornamented variation when he did, etc. Yet there were a few landmarks in the landscape of his mighty work that I felt I would like to incorporate into my feeble effort, in particular the moving slow and lyrical variations to be found, one towards the end of the first half and one halfway through the second, and also the rumbustious knockabout variation with which he concludes. I had also, like all listeners to the work, been struck by the fact that Bach does not, after the Aria, begin with any sort of overture, but keeps that back till variation 16, the start of the second half. I decided that for that grand piece ‘in the French style’, I would transpose another Bach anecdote to late eighteenth century England. The story goes that by the end of his life Bach’s fame and his ability to improvise complex music had spread to the court in Potsdam, and it was there that the King invited him and gave him a theme which he asked him to improvise on. The result was another astonishing masterpiece, The Musical Offering. I decided that my naturalised English writer would also compose a number of variations on a theme given him at court by George III.

I had had a postcard of an extraordinary late work by Paul Klee on my desk in Lewes for some time. Called Wander-Artist, which means something like travelling showman and performer, it depicts, in stark black, a crudely drawn figure striding from left to right across a red background, itself hemmed in by a rough black frame, and waving as he goes. The whole is painted to look more like a poster than an artwork, and I loved it and was moved by it, for reasons I could not begin to fathom. But as I worked with renewed energy on my homage to Bach that figure suddenly intruded into the fiction and even began to speak. That was when I knew that finally the thing was coming together and one day I would have a book.

When it was done and I had my thirty variations I racked my brains to try and decide how to compose the Aria that in Bach starts and finishes the work. And it gradually dawned on me that that may be the difference between our age and the age of Bach, that his can have an opening and closing Aria, which anchors the piece and set the parameters, while ours can only have variations. In other words, there was a good and profound reason why I could not find it in me to write my Aria. And with that thought came the further thought that for this book the Aria would have to be the Klee Wander-Artist, which I would ask the publisher to put on the front and back covers, as though the only Aria for us to countenance today would have to be a collage onto mine of someone else’s work, and would be a work that itself cast doubt on the notion of the artist, suggesting as it does, like other works of Klee, such as Ghost of a Genius, that today the word can only be used mockingly, artist reduced to artiste, genius to ghost.

With that my work on the book came to an end. But my feeling, after working at it for far longer than for any of my other novels, was mainly one of relief, not of triumph. And of course it was the first novel of mine that I could not show to my mother. As to whether it’s all that different from my other works, I’m not sure. In some ways of course it is, and I’ve tried to explain why. But the central figure of the Wander-Artist is another of my walkers, isn’t he? His roots I think probably go back to Migrations. But it’s really not for me to say.

VB: Goldberg was received wonderfully well in France. Reading the reviews, I feel they really ‘got’ you, if you know what I mean. As you mentioned with the German reading public, they responded so deeply to what you are doing in your fiction. I wonder why your writing works so well with a European sensibility that seems lacking in the Anglo-Saxon temperament of the British?

GJ: But it took twelve years to appear in translation. Haffmans Verlag had commissioned a translation but the firm went bankrupt before they could publish it, and so far no other foreign publisher has dared take it on, apart from Quidam, my intrepid and wonderful French publisher, who brought it out last year. I did finally feel then that I had found my public, something, as I said earlier, that I had hoped for with Contre-Jour but which never materialised at the time.

As to why my books get more intelligently reviewed in Germany and France, there must surely be many reasons. There is now a clear divide between the cultural life in England and America on the one hand, and on the continent on the other. You go into a French bookshop and the main table is spread out with books on philosophy; in an English bookshop, with books on food or gardening, or with biographies of footballers. The Net Book Agreement holds in France and hardly anyone uses Amazon, preferring always to buy through their local bookshop. And there are still several of these, independent bookshops, in every quarter of Paris, each with its devoted band of readers. Bernard Hoepffner, my brilliant French translator, and I read together from Goldberg in a small Paris bookshop last year. We occupied the only two seats they could get into the small space, but it was packed with people who had already read the book, listened attentively, and asked good questions, standing for over two hours. And that’s not just true of Paris, but of most French towns. With Bernard we took the train to Tours and read in a bookshop there (the tickets and our hotel paid for by the bookshop owner). Same story, except that the place was big enough for seats to be brought in. Drinks were served afterwards. When we did the same in Brussels, the owner said he couldn’t stay to have dinner with us. He had made his money, it turned out, in business, and then at the age of 30 retired and started the bookshop. At ten that night he was taking part in a 160-kilometre bicycle event. So he was living the life he wanted to live. In England I suspect someone in his position would have opened a wine-bar. So it’s a whole cultural thing. Proust, Blanchot, Merleau-Ponty, Derrida, Mann, Heidegger, Celan, are living presences for most educated readers in France and Germany. In England? One just has to ask the question to see the problem.

It’s a shame, though, because I feel a dose of English irony and even scepticism would sometimes be useful when French or German intellectuals ascend into the stratosphere, and I love the deflationary irony of the best of Evelyn Waugh and Kingsley Amis. But it can so easily become a cheap and sneering cynicism, which is really a kind of schoolboy panic in the face of what they feel is beyond them. In their disciples only the cynicism is left.

VB: I’d like to mention a couple of your novellas, now, beginning with Everything Passes, the first of your books I read and still one of my favourites. The pliancy of this narrative astonishes me every time. Can we talk about white spaces? They’re a feature of several of your works and give them a particular, striking effect. What does that blank space bring to your narrative, do you think?

GJ: Not sure I can answer your questions, but I’ll have a go. First of all, ‘novellas’. I don’t know when the term was invented, but it is clearly helpful when the expected length for a novel was between 500 and 1000 pages. It helps us distinguish Bartleby from Moby Dick and The Death of Ivan Ilych from War and Peace. But I’m not sure it’s helpful with the modern writers I’m interested in – Woolf, Spark, Duras, Bernhard, Appelfeld – very few of whom write long books. Proust wrote one enormous work of fiction, basically, but the many short novels of Woolf or Bernhard can also be seen as parts of a single project. Whether my books should be seen like that or not it’s not for me to say – they certainly feel like that from the inside.

I’m glad you responded to Everything Passes – I had been thinking about it for a decade or two before I wrote it and a great many different elements went into it – hearing Schoenberg’s late String Trio, that extraordinary expressionist work which, he said, attempted to describe what he felt like when he technically died and had to be resuscitated with an injection; a photo of Francis Ponge looking out of a dirty window with a broken pane I once saw in a newspaper and could never forget; much else. But you are asking me about the way it is written. One of my earliest pieces is a long ‘story’ called ‘Distances’. I think the epigraph is from Rilke: ‘those feelable distances’. I am drawn to the idea of the distance between people, and even between ourselves and ourselves, as a space that is vibrant with unspoken feeling. The works of art that touch me are those where that is in play – in Vermeer’s painting, in Velazquez’ Las Meninas, in Hammershøi’s silent rooms – works which have an enigmatic quality, a sense of waiting for something to happen, where the waiting is more important than the happening. I love the idea of a work of fiction which can catch that. And as I discovered with The Inventory, you really don’t have to spell out the transitions, and you can use repetition to convey rhythm. I love the border ballads for that reason, and the late medieval ballades and many of Dunbar’s poems. As with the Aria in the Goldberg Variations, these refrains and repetitions are never exactly the same when they return, precisely because now they have been heard before. And I suppose I’ve never got over my first hearing of those long slow works of Maxwell Davis and Birtwistle which seem quite static but where something is slowly stirring and by the end you find you have travelled a long long way, even if that way is not linear.

Does that start to answer it?

VB: Also in Everything Passes, your protagonist, Felix, discusses Rabelais and the moment in European culture when Rabelais understands that he has ‘gained the world and lost [his] audience’. I wondered what you felt about that in relation to contemporary audiences. Do you think we are undergoing another seismic shift in terms of the reader and his or her capacity for attention and understanding?

GJ: You know, I wanted Felix to sound pompous and just gave him something pompous to say. Schoenberg, who is vaguely behind Felix, lost his first wife to a much younger friend. I suspect she could not bear his ponderous certainties, his propensity to lecture one at the slightest opportunity. But of course I stand by the gist of his comments. I do think Rabelais and the whole tradition of which he is the head – Cervantes, Sterne – wrote out of just such a sense of print as both liberating and crippling. But whether this is being repeated today – are you referring to the internet etc? – I wouldn’t know. I still read books and trust that anyone who bothers to read me will do the same. And, interestingly, Patrick Wildgust, the director of the Laurence Sterne Trust who runs Shandy Hall, tells me he is sure the renewed interest of young people in Sterne has something to do with the internet. People blame the internet, he says, for sapping readers’ ability to stick with a linear narrative for several hundreds of pages, but by the same token Sterne, who is all digression and no linearity, is the ideal author for the internet age. Of course there are few works with the originality and zest of Tristram Shandy, and I suspect one needs to know how to commune with a book in silence to respond to Woolf or Duras or Bernhard.

VB: After is an extraordinary novella (published in a Carcanet edition with Making Mistakes). There’s an exchange in it that thrills me: ‘genuine puzzlement is much more productive than false clarity’, your protagonist says, to which comes the reply: ‘I wonder if your theory is not a little dangerous when applied to life and not to the problems of the mind.’ What gave you the idea for this story with its profound exploration of memory and knowledge?

GJ: I’m so glad you like After – and was so moved by your review of it when it came out all those years ago. It was another of those books which just refused to come. I eventually forced my way through to the end in a rather tense period of six months I spent in Paris, teaching once a week at the American University. I had had a bad two or three years in my personal life, compounded by the fact that my German publisher had gone bust and Carcanet were uncertain whether they would be able to go on publishing fiction at all. Writing it was a kind of lifeline for me. I felt I just had to write it to stay sane, and in fact it’s a pretty mad novel. I don’t know what I think of it. In a way it’s a reprise of The Echo-Chamber. At times I feel deeply embarrassed by it and ashamed of it, at others very proud. I can’t say any more than that.

VB: We haven’t really talked about your short stories. Would you like to say a few words about them?

GJ: There are writers like Bellow for whom short stories are really shards dropped from the novels or ideas for novels that never quite developed. And there are writers like Beckett and Robbe-Grillet who used the short story form to test out their style and vision in their early years. There are also writers like Borges or Ambrose Bierce whose fictional output consists of nothing but short stories. And finally there are those, like Hawthorne or Malamud, who have written both short stories and novels and recognised that these are rather different forms, each with its strengths and its weaknesses. I feel I belong to this group. I’ve always loved short stories, enjoy the fact that you can control every word in them in ways you can in a poem but not a novel, and some of my happiest moments have come when I realise I have finally nailed one. This happened with one of my earliest, ‘Mobius the Stripper’, with a small group of stories I wrote in the eighties, ‘Second Person Looking Out’, ‘He’, ‘That Which is Hidden is That Which is Shown…’, ‘Steps’ and ‘Volume IV, pp.167-69’, and with a couple of more recent ones, ‘He Contemplates a Photo in a Newspaper’ and ‘Heart’s Wings’. In fact, I’m not sure, if I were asked which of my books I feel happiest to have written, if I would not plump for ‘Heart’s Wings’ and Other Stories, a volume of recent and selected earlier short stories which Carcanet published in 2010, with a fine cover designed by my son.

VB: You used to write stage and radio plays. Why did you stop?

GJ:After my first two novels had been published a theatre was built in the new University where I had gone to teach, at Sussex, and the students asked me to write several plays for them. The challenge was very exciting. I wrote a monologue for Nick Woodeson, who later rose to become a distinguished actor, one of those Pinter regularly turned to, and two plays for a group of students. Then I worked very intensely on a collaboration with the Australian composer, Peter Sculthorpe, who had come to the University as a visiting professor while he was trying to get started on an opera commissioned for the opening of the Sydney Opera House. Our collaboration came to nothing, but as a result of our discussions and my immersion in things Australian I wrote a play, Dreams of Mrs Fraser, which was premiered at the Royal Court Upstairs. Then for a while I wrote for the little theatres which were starting to proliferate in Britain in the early seventies. Unfortunately they soon started to concentrate on more overtly political kinds of drama, and I found that my plays fell between two stools: too ‘avant-garde’ for the conventional stages but not political enough for the little theatres. Later, and for several years, I teamed up with a Brighton-based company, and wrote a number of lunchtime pieces for them, but they eventually disbanded and commissions dried up. I find that while I will always write fiction, which I do on my own in my own time, and which, thank God, I have always eventually found publishers for, with the theatre you have to have a specific commission, to know what kind of company and space you are writing for, even though you always hope that if the work is good enough it will find other homes elsewhere after a first outing.

I did have one very exciting commission at the time. The newly-formed Actors’ Company, which included Ian McKellen and Caroline Blakiston, invited me to write a half-hour play for five actors, with minimal props as they were short of funds, to be performed at lunchtime in Edinburgh where they were doing a season of Shakespeare and Chekhov. In half an hour you can’t really waste time having people go in and out, so this forced me into attempting something I had only ever half-thought about: a play of five intertwining monologues performed by actors seated facing the audience. I had always felt that my trouble with most post-Renaissance art is that you are meant to face it head on, while it stands still, so to speak, and stares back at you. Yet in life things are constantly slipping past us, just caught out of the corner of the eye, or only half-heard. I liked the idea of an audience trying to hold all five monologues in mind at the same time but of course being unable to do so, and gradually letting go of some in order to make sense of one or at most two. The rehearsals were very exciting, my brilliant and virtuoso cast rising to the challenge I’d set them. The trouble was there was no room for hesitation, and if you lost your place there was no way of finding it again. And invariably one or other of the cast would lose their way. In the end the director, Edward Petherbridge, had to decide whether to keep going with rehearsals to the end and hope for the best or cut his losses and set up lecterns in front of each so that they could read the words. And this is what he did. The result I felt (and Howard Hobson in The Sunday Times, agreed with me) was unnerving and powerful, but it was not nearly as powerful as it had been in rehearsal, where the actors’ anxiety and fear of not getting to the end without coming unstuck, became part of the tension of the whole and where their very vulnerability in front of the audience made for very powerful theatre. The play has been done once or twice since, but always with lecterns, and I long to see it done without. It would have to be a young and fearless company to do it though.

Flow, as I called it, and Comedy, the second of the plays I wrote for the Sussex students, and which almost got done professionally in a boxing ring, which would have been perfect (the backers pulled out at the last moment) – these are the plays I’d most like to see revived in really bold productions.

Though work in the theatre dried up by the end of the seventies, I was starting to write quite a lot for radio. I had always loved the idea of radio drama and in the radio drama team at the BBC, I found I had people who believed in me and were prepared to commission work with absolutely no strings attached. The result was a series of very happy collaborations, from Playback in 1973 to the mid-eighties. When Guy Vaesen retired (though he returned to produce my 90 minute monologue, Vergil Dying, written for Paul Scofield and performed by him on radio) I teamed up with another fine producer, John Theocharis and together we worked on a number of productions, two of which were chosen by the BBC as entries for the Italia Prize, AG, a mad and highly irreverent reworking of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, and Mr.Vee, an attempt to find an audial equivalent for the play of mirrors in Velazquez’s Las Meninas. Many of them were also translated into German, for Germany has a rich tradition of the Hörspiel. But by the nineties the BBC had begun to change, The Third Programme had become Radio 3, a mainly musical station, and had lost its glittering array of distinguished producers, while in Germany too the effects of reunification were felt even in the rarefied world of the Hörspiel, and there was a severe reduction in their transmission of foreign plays. I greatly miss those intense two or three days of working with dedicated actors and producers of the highest calibre, but it looks as if the days of really innovative radio drama are gone for good.

VB: I have concentrated on your fiction in this interview, because I feel that that is where you’ve done your most important work. But there is a question anyone who has read your criticism as well as your fiction will want to have answered, and that is what you consider the relation between the two to be. You’ve pointed out again and again in your answers to my previous questions that fiction certainly does not spring for you from any desire to make critical or theoretical points. But where then do you see your criticism, which is fairly substantial, with books on subjects as diverse as the Bible, the sense of touch, the notion of trust, and Modernism, fitting into your oeuvre as a whole?

GJ: I said at the start, talking of the genesis of The Inventory, that I thought I would have to give up teaching because living with books, talking about books all the time, made me unduly self-conscious and made it impossible for me to write my own fiction. But I wrote that novel and stayed on teaching at Sussex for 35 years, the last fifteen or so part-time, teaching from October to March and having April to September to myself. This actually was ideal. I did something I enjoyed doing and that I felt was worthwhile, so that even if I got nowhere with my writing I could still feel, at the end of the year, that I had made a contribution of some kind to the country that had after all taken me in and given me free university education with a job at the end of it. On the other hand come April I was not exhausted mentally and physically, as I had been by the end of June when I taught full time. In fact I had a free conscience and I felt I had earned my time to myself, so that those months of April and May were utterly blissful and a time of great creative upsurge. Since I’ve retired completely I don’t get that lift and if the work is not going well I have nothing to take its place, while I rarely feel I’ve earned any sort of break.

But teaching literature and writing criticism are not the same thing at all. I have always felt that writers make the best critics, and love the critical writings of Proust, Woolf, Auden and Mann, and the comments on books and writers one finds in the letters of Lawrence and Eliot and Beckett. Writing about the books and authors you love seems a natural extension of writing your own fiction or poetry, a little less fraught of course, since the threat of failure is not so imminent – I will always be able to finish an essay on a writer I love or a topic that interests me, but that is certainly not true of a story or a novel. In fallow periods Pinter turned to writing film scripts. They are often very good, and clearly by him, but obviously not of the same importance as his major plays. Alas, no-one asks me to write film scripts, and that is why in fallow periods I have found myself accepting reviewing and other non-fiction commissions or even following up an idea and writing a whole non-fiction book, as with Touch.