Patrick J. Keane’s “Wordsworthian Sources” bears a title that slightly masks its poignant and human subject matter, that is, Emerson’s struggle to come to grips with the death of his beloved brother Charles from tuberculosis. It’s a beautiful essay, densely argued, replete with quotation, and full of link-lines to other essays Pat has published in Numéro Cinq, which taken together begin to look like a book on the Emerson-Wordsworth-Nietzsche-Twain constellation. What Pat does here is focus on the nexus of emotion (mourning), reading and tradition that helped form Emerson’s reactions to his brother’s death, the mental processes by which he dealt with his emotional surplus, as it were. Emerson finds, yes, hope in Wordsworth’s poems, but is not blinded by hope, is rather fascinated by the will to believe (that is, he foreshadows the modern move from ontology to phenomenology). He tries to honour his brother by setting his papers in order for publication, only to find them surprisingly inadequate. He even reaches for solace into a chilly transcendentalism, for which he is sometimes castigated. As always Pat Keane, immerses his readers in a world of the mind, a world of books (are they different?), the heady and inspiring world of great writers talking together.

dg

—

We tough modernists are frequently put off by Emersonian “optimism,” whether depicted as Emerson’s refusal to face hard facts, his lack of a “tragic vision,” or, more personally, as a relentless serenity and untroubled cheerfulness that can, at times, seem less admirable than repellent: an Idealist or Stoical detached tranquility bordering on coldness. There is, of course, some truth in this latter characterization, and Emerson will never be everyone’s cup of tea, especially in an age that prides itself on confronting dark realities and peering into the abyss. I come neither to praise Emerson’s equanimity nor to condemn his inveterate optimism and his more-than-occasional emotional chilliness. Instead, I’d rather try to understand where he’s coming from by exploring just a few sources of Emersonian “hope,” his ability, or determination, to find “light” in even the most profound darkness.

Aware of the traditions in which, and precursors in whom, he was spiritually, intellectually, and emotionally steeped, one might expect a Transcendentalist Emerson besieged by painful circumstances to turn primarily to his religion; or to the perennial philosophy of Plato and Plotinus; to the Stoicism of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius; to the Milton who offers, directly or through angelic personae, recompense for even the most grievous loss. Above all, perhaps, one might expect the more “realist” side of Emerson to fall back on his cherished Montaigne, that world-renowned counselor and practitioner of tranquility of mind and a constructive calmness in affliction—especially since Montaigne was no more a stranger to what Emerson called the “House of Pain” than was Emerson himself, who suffered, in a single terrible yet productive decade (1831-42), a harrowing sequence of familial tragedies. He does find comfort in these traditions and writers, but I want on this occasion, and in this context, to emphasize the crucial importance to Emerson of his reading of Wordsworth, in particular as a source of consolation in the immediate aftermath of the death of his dearest brother, Charles, in 1836.

The caricature of Emerson as an unfeeling man whose optimistic theory so blinded him to a vision of evil as to render him incapable of experiencing pain and suffering may be corrected by examining, through a Wordworthian lens, Emerson’s response to, and frequent transcendence of, harsh and apparently unregenerate reality: what Keats, in one of his remarkable letters, called “this world of circumstance,” a Vale of Tears we struggle to convert into a secular “vale of Soul-Making.” Like so many others in the nineteenth century, Keats was immersed in, and responding to, the same Wordsworth poems that shaped Emerson: “Tintern Abbey,” the “Prospectus” to The Recluse, the meditations of the Wanderer in The Excursion, and, above all, that Emersonian favorite, the great “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”—the ninth stanza of which was Emerson’s principle source of consolation in distress.

The caricature of Emerson as an unfeeling man whose optimistic theory so blinded him to a vision of evil as to render him incapable of experiencing pain and suffering may be corrected by examining, through a Wordworthian lens, Emerson’s response to, and frequent transcendence of, harsh and apparently unregenerate reality: what Keats, in one of his remarkable letters, called “this world of circumstance,” a Vale of Tears we struggle to convert into a secular “vale of Soul-Making.” Like so many others in the nineteenth century, Keats was immersed in, and responding to, the same Wordsworth poems that shaped Emerson: “Tintern Abbey,” the “Prospectus” to The Recluse, the meditations of the Wanderer in The Excursion, and, above all, that Emersonian favorite, the great “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”—the ninth stanza of which was Emerson’s principle source of consolation in distress.

Had we world enough and time, I would also discuss some of the many short Wordsworth consolatory lyrics Emerson loved, as well as the two substantial Wordsworth poems, “Laodamia” and “Dion,” that he consistently ranked second only to the Ode. These two poems, both based on classical sources, epitomize Emerson’s attraction to Wordsworthian austerity and to elegy: a genre that traditionally balances suffering with some form of compensation. Emerson believed, as Wordsworth put it in the remarkably balanced final line of “Elegiac Stanzas,” that it is “Not without hope we suffer and we mourn.” That kind of hope, allied with the Ode’s “truths that wake/ To perish never,” provided Emerson (who repeatedly alludes to these very passages) with light in the darkness as he struggled, personally and philosophically, to reconcile his philosophy with a harsh reality most painfully embodied in the early deaths of those he most loved.

1

In 1836, five years after the death of his young wife Ellen and two years after the death of his younger brother Edward, Emerson’s closest brother, Charles, succumbed to tuberculosis. The two had just been reading Sophocles’ Antigone and Electra, with Emerson—as Charles, the superior Greek scholar, told his fiancée, Elizabeth Hoar—“quite enamoured of the severe beauty of the Greek tragic muse.” To be thus enamored is to go some distance, at least aesthetically, toward what Emerson would call, a decade and a half later in his essay “Fate,” submission to the essence of Greek Tragedy: the will of Zeus in the form of “Beautiful Necessity”—or what Emerson’s disciple Nietzsche would later celebrate as amor fati. A month after their reading of Antigone, Charles, as though to put the beauty of tragedy to the test, was dead. Emerson wondered, as he turned from the grave with an enigmatic laugh, what there was left “worth living for.” Two weeks later, though declaring that “night rests on all sides upon the facts of our being,” he added we “must own, our upper nature lies always in Day.” (L 2:19, 20, 25)

Lying “in Day” and associated with the “light of all our day” in Wordsworth’s Ode, that “upper nature” reflected a higher law. Underlying all pain and tragic suffering, Emerson detected a “spiritual law” allied with Antigone’s pronouncement of an immutable higher law. In “Experience,” the great essay so closely related to perhaps the most devastating of all his familial tragedies, the death in 1842 of his little boy, Waldo, Emerson repairs to the locus classicus of that law: “Since neither now nor yesterday began/These thoughts, which have been ever, nor yet can/ A man be found who their first entrance knew” (E&L 473). Emerson is translating, rather awkwardly, from one of the most famous speeches in Greek tragedy. Responding to Creon’s charge that, in burying her brother, Polyneices, she had violated royal “laws,” Antigone archly observes that she did not think that Creon’s edicts, those of a mere mortal even if a king,

……….could over-run the gods’ unwritten and unfailing laws;

Not now, nor yesterday’s, they always live,

And no one knows their origin in time. (Antigone, lines 455-57).

This is the earliest, often-cited statement of the eternal, unwritten justice (themis): the inner, supreme, spiritual “law,” its origins unknown in time and for that very reason imperishable. The truths of this unwritten and immutable divine law are opposed to human, written legislation (nomoi), civil proclamations here today and gone tomorrow. These are the ever-living “truths that wake,/ To perish never,” to which Emerson repeatedly refers, quoting, as he almost obsessively does, from the numinous ninth stanza of Wordsworth’s Intimations Ode. As Emerson had said earlier in this paragraph of “Experience,” underneath the vicissitudes of chance and life’s “inharmonious and trivial particulars,” there is a “musical perfection, the Ideal journeying with us, the heaven without rent or seam,” in the form of a “spiritual law,” revealed to us by the very “mode of our illumination” (E&L 472).

That “illumination” is allied with the assertion that “our upper nature lies always in Day,” a phrase that deliberately echoes the repetition of “day” in Wordsworth’s Ode: not the fading (in the poem’s opening stanza) of celestial radiance “into the light of common day,” but that Plotinian “fountain light of all our day”—the line of the Ode to which Emerson most frequently alludes. The “Child” of the middle stanzas of the Ode had been addressed as “Thou, over whom thy Immortality/ Broods like the Day.” Wordsworth was at once sublime, certain, and vague about the source of that fontal light; he gives thanks for “those first affections,/ Those shadowy recollections,/ Which, be they what they may,/ Are yet the fountain light of all our day,/ Are yet a master light of all our seeing.” It is in this luminous yet shadowy region, a region of mastery rather than servitude, that, Emerson insists, “our upper nature lies”: Experience’s version of Wordsworthian blissful Innocence, when “Heaven lies about us in our infancy.”

The central issue, as confirmed by the title of Wordsworth’s Ode, has to do with “intimations of immortality” drawn from recollections of our earliest childhood when, in Platonic and Neoplatonic theory, we were closest to Eternity. By 1836, Emerson was having increasing difficulty believing in either a personal divinity in the sense of a god external to the self, or in a conventional, religiously orthodox sense of immortality. He had only that Wordsworthian and Plotinian presence brooding over him “like the Day.” What Wordsworth and Emerson, like Plotinus, describe as intuitive gleams do not pretend to be “rational” demonstrations, nor are they conventionally supernatural. What then, Emerson asks in his essay “Immortality,” is the source of the mind’s intimations of eternity or infinity? “Whence came it? Who put it in the mind? It was not I, it was not you; it is elemental….” It is also, for a reader of the Romantics, elementally Wordsworthian, mysterious and yet certain; a “gleam” and “a master-light”—which Emerson habitually, and significantly, altered to “the master light.” This “wonderful” idea, he says, “belongs to thought and virtue, and whenever we have either, we see the beams of this light” (W 8:333).

This “light of all our day,” along with inextinguishable “hope,” provide the crucial terms, for in assuming what is both mysterious and unproveable, Emerson is falling back on Wordsworth as his apostle of “hope” and his authority on the intuitive, rather than the cognitively demonstrable. As he said in all versions of “Immortality,” beginning with the 1861 lecture on which the essay was based, he would “abstain from writing or printing on the immortality of the soul,” aware that he would disappoint his readers’ “hungry eyes” or fail to satisfy the “desire” of his “listeners.” And, he adds,

I shall be as much wronged by their hasty conclusions, as they feel themselves wronged by my omissions. I mean that I am a better believer, and all serious souls are better believers in the immortality, than we can give grounds for. The real evidence is too subtle, or is higher than we can write down in propositions, and therefore Wordsworth’s “Ode” is the best modern essay on the subject. (W 8:345-46)

“We cannot,” Emerson continues in the very next sentence, “prove our faith by syllogisms.” This is yet another variation on the familiar point that the “shadowy recollections” and “visionary gleams” of numinous intuition cannot be categorized or proven—“be they what they may,” as Wordsworth says in the Ode, acknowledging his own ignorance of ultimate mystery. Nevertheless, those intuitive and compensatory gleams of light remain indisputable—proven, as it were, on the pulses. Wordsworth, like Emerson after him, anticipates the related but more recent “Testimony” (1999) of W. S. Merwin:

I am not certain as to how

The pain of learning what is lost

Is transformed into light at last.

Yet, as usual in Emerson, who refuses to dogmatize obscurity into a facile clarity, what matters is not doctrine but the mysterious, yet irresistible affirmative instinct. As he says, again in his crucial essay “Experience,” it “is not what we believe concerning the immortality of the soul and the like, but the universal impulse to believe, that is the material circumstance and is the principal fact in the history of the globe” (E&L 486; italics added). It is a matter, as Tennyson would put it in In Memoriam, of “Believing where we cannot prove”; or, as it was famously phrased by William James (who found that he could not obey his own imperative): “the will to believe.” Emerson was capable of correcting even what he took to be Wordsworth’s position when it came to the indispensable Intimations Ode. Mistakenly expanding Wordsworth’s comment about his employment of Platonic or Neoplatonic myth (making the “best use” he could of it “as a poet”) into authorial judgment on the revelations of the poem as a whole, Emerson, trusting the tale and not the teller, rose to the Ode’s defense: “Wordsworth wrote his ode on reminiscence, & when questioned afterwards, said, it was only poetry. He did not know it was the only truth” (TN, 2:262).

Though, even in the days immediately following Charles’s death, Emerson would echo the Ode in asserting that “our upper nature lies always in Day,” his own battered faith during this “gloomy epoch” offered little religious consolation in bereavement. We see the gloom in “Dirge,” a heartbroken 1838 elegy for his two brothers, his “strong, star-bright companions,” in which he envisioned, not a Christian heaven, but a classical or pagan sunset plain “full of ghosts” now “they are gone.” A more hopeful variation occurs in lines originally included in his long poem, “May-Day,” but subsequently extracted to form the conclusion of Emerson’s still-later poem, “The Harp.” “At eventide,/ …listening” for “the syllable that Nature spoke” (but which, aside from the “wind-harp,” has been “adequately utter[ed]” by none, not even “Wordsworth, Pan’s recording voice”), the old poet suddenly finds himself in the visionary presence of the lost companions of his youth:

O joy, for what recoveries rare!

Renewed, I breathe Elysian air,

See youth’s glad mates in earliest bloom…..

The “Aeolian” harp and “Elysian” air are classical, but Emerson is once again (if rather feebly) echoing the Intimations Ode. The recovery-stanza (his favorite) opens with the same exclamation—“O joy! That in our embers/ Is something that doth live,/That Nature yet remembers/ What was so fugitive!”—and ends with a vision of immortal “children” sporting on the shore of eternity. In the lines that immediately follow in his own poem, Emerson concludes by expressing the hope of an eternal Spring beyond the intruding grave: “Break not my dream, intrusive tomb!/ Or teach thou, Spring! The grand recoil/ Of life resurgent from the soil/ Wherein was dropped the mortal spoil.”

After three weeks of mourning the death of Charles, Emerson concluded that “We are no longer permitted to think that the presence or absence of friends is material to our highest states of mind,” for personal relationships pale in the light of the “absolute life” of our relationship to the divine. This austerely Neoplatonic perspective will emerge in the seminal if paradoxically-titled Nature, in that highest state when Emerson, “uplifted into infinite space,” becomes “a transparent eye-ball” and the “name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances…is then a trifle and a disturbance” (E&L 10). This epiphany is Emerson’s partial compensation for the loss of Charles. “Who can ever supply his place to me? None….The eye is closed that was to see Nature for me, & give me leave to see” (JMN 5:152). Now Charles’s metaphorical transmutation into an all-seeing but impersonal eye-ball leaves Emerson at once exhilarated and isolated, friendship reduced to the foreign and accidental, even brotherhood a trifle. Similarly, “Experience,” written in the aftermath of little Waldo’s death, will proclaim the “inequality between every subject and every object,” and, consequently, the superficial nature of grief and love: “The great and crescive self, rooted in absolute nature, supplants all relative existence, and ruins the mortal kingdom of friendship and love.” There is a “gulf between every me and thee, as between the original and the picture.” The soul “is not twice-born, but the only begotten,” and admits “no co-life,” since “We believe in ourselves as we do not believe in others” (E&L 487-88).

Emerson’s notorious announcement, earlier in “Experience,” that the loss of his precious boy “falls off from me, and leaves no scar. It was caducous” (E&L 473; italics added), is related to those idealist, sense-transcending “High instincts” at the center of the pivotal ninth stanza of the Intimations Ode. The offensive word, so deliberately and coldly technical, is of course “caducous,” which more often describes a floral or organic rather than a human “falling off” of connected but separable parts (leaves, or a placenta). Emerson’s point can be clarified, if not made much more palatable, by being compared to “those obstinate questionings” (again, in the ninth stanza of the Ode) “Of sense and outward things,/ Fallings from us, vanishings….” But if Wordsworth is abstract and austere in the ninth stanza, the crux of the Ode, Emerson seems, in “Experience,” positively cold, far removed from the spiritual and humane hope, expressed at the time of Ellen’s death, that he might retrieve that lost “beautiful Vision” by entering with her into what (echoing Milton’s “Lycidas”) he calls “the great Vision of the Whole” (JMN 3:230-31). In his new thinking, reflecting both a genuine Idealist vision of transcendence (as in the epiphany of the transparent eye-ball) and a need to numb himself to the pain of repeated loss, the human beings we love, the living and the dead, are said to have nothing to do with the “absolute life” of one’s relationship with God; for in “that communion our dearest friends are strangers. There is no personeity in it” (L 2:21; JMN 5:150-61, 170).

We may be reminded of what Keats termed “the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime.” For this is Transcendentalist Emerson at his most aloof and least humane, a momentary scandal to even his fiercest worshiper, Harold Bloom. But Emerson was, fortunately, not utterly caught up in his own theory of a friend-estranging and personality-excluding communion with God. Thus, collaborating with Charles’s fiancée, Elizabeth Hoar, he first sought for his brother a literary immortality by trying to put the dead man’s scholarly writings—that “drawer of papers” that formed Elizabeth’s heritage—into shape for publication. He was no more successful than Montaigne had been in his similarly doomed attempt to adequately represent his friend La Boétie by posthumously publishing his papers. In fact, Emerson was shocked to discover from Charles’s journals just how “melancholy, penitential, and self-accusing” his destructively-ambitious and self-doubting brother had been. He found “little in a finished state and far too much of his dark, hopeless, self-pitying streak,” the “creepings of an eclipsing temperament over his abiding light of character” (JMN 5:152). Emerson’s own affinities, in precise contrast, were with a finally uneclipsed and abiding light, hope, and self-affirmation. Writing on March 19 after having read Charles’s “noble but sad” letters to Elizabeth, letters containing “so little hope” that they “harrowed me,” Emerson declared no book “so good to read as that which sets the reader into a working mood, makes him feel his strength….Such are Plutarch, & Montaigne, & Wordsworth” (JMN 5:288-89). We can trace his recovery from the blow of Charles’s death in a crucial journal entry—one centered less on Plutarch or Montaigne’s “On Friendship,” than on Wordsworth, this time quite explicitly.

2

Writing in mid-May 1836, after ten days of “helpless mourning,” Emerson begins, tentatively, to recover. “I find myself slowly….I remember states of mind that perhaps I had long lost before this grief, the native mountains whose tops reappear after we have traversed many a mile of weary region from our home. Them shall I ever revisit?” These “states of mind” are reflected in the conversation of friends who have “ministered to my highest needs,” even that “intrepid doubter,” Achille Murat, Napoleon’s nephew, with whom Emerson had “talked incessantly” nine years earlier, during his return from his recuperative trip to Florida (JMN 3:77). The “elevating” discussions of such men, and these men themselves, “are to me,” says Emerson, “what the Wanderer” [in Wordsworth’s Excursion] is to the poet. And Wordsworth’s total value is of this kind….Theirs is the true light of all our day. They are the argument for the spiritual world for their spirit is it” (JMN 5:160-61).

Emerson was particularly impressed by the Wanderer, the composite character in whom Wordsworth concentrated, not all, but most of his own thoughts and feelings, and who reminded Emerson of his idealist friend Bronson Alcott. In Book 4 (“Despondency Corrected”) of The Excursion, Wordsworth has the Wanderer draw comfort from men such as himself: men whose hearts and minds, shaped in nature’s presence and able to convert pain and misery into a higher delight, attain a humanity-glorifying form of tragic joy. Such men are “their own upholders, to themselves/ Encouragement, and energy and will.” But there are others, “still higher,” who are “framed for contemplation” rather than “words,” words being mere “under-agents in their souls.” Theirs “is the language of heaven, the power,/ The thought, the image, and the silent joy.” And “theirs,” as Emerson says of such ministering men and once again echoing the Ode, “is the true light of all our day.” Familiar with The Excursion as early as 1821, when he inscribed in his journal a synopsis of its nine books (JMN 1:271-72), Emerson would have endorsed the following accurate synopsis, by critic Charles J. Smith in a 1954 PMLA essay on Wordsworth’s “dualistic imagery”:

Throughout this long poem, filled with the aspirations, struggles, and heartaches of humanity, Wordsworth tells us that even in the very midst of Mutability, loss and grief, there are, to the practiced eye, signs and symbols of eternal rest and peace. The Wanderer has the wisdom to perceive and the feelings to appreciate these symbols and has faith in what lies behind them.

Parts of the opening Book of The Excursion have always been admired, especially the account of the Wanderer’s boyhood (a Wordsworthian seed-time in Nature’s presence, much cherished by Emerson) and his tale of Margaret and the Ruined Cottage. But it was Book 4, “Despondency Corrected,” that many readers (including Lamb, Keats and, Ruskin; Emerson, his Aunt Mary, and his poet-friend, Jones Very) considered not only the best thing in The Excursion, but among the supreme achievements of Wordsworth’s career. Indeed, it was his previous experience in reading Book 4, and absorbing the philosophy and consolation offered by the Wanderer to the despondent Solitary, that made Emerson confident, when he picked up the latest volume of Wordsworth’s poetry seeking consolation in the painful aftermath of Charles’s death, that he would “find thoughts in harmony with the great frame of Nature, the placid aspect of the Universe” (JMN 5:99).

Anticipating Emersonian “optimism” and his precise dialectic of “conversion” in the essay “Compensation,” the Wanderer, a Romantic Stoic, describes in Boethian/Miltonic terms the operations of benign Providence, ever converting accidents “to good” (4:16-17). In his great speech at the opening of the final Book of The Excursion, the Wanderer tells his listeners, echoing his own earlier metaphor of the “fire of light” that “feeds” on and transforms even the most “palpable oppressions of despair” (4:1058-77), that

The food of hope is meditated action; robbed of this

Her sole support, she languishes and dies.

We perish also; for we live by hope

And by desire; we see by the glad light

And breathe the sweet air of futurity

And so we live, or else we have no life. (9:21-26; italics added)

Though far too heterodox a believer in the God within to be in accord with every aspect of the Wanderer’s religiosity, Emerson, through allusion and influence, in effect records his agreement with the Wordsworthian “Author,” in the coda to Book 4: that the words uttered by the Wanderer “shall not pass away/ Dispersed, like music that the wind takes up/ By snatches, and lets fall, to be forgotten.” They “sank into me,” Emerson could say as well, the Wanderer’s words forming the “bounteous gift”

Of one accustomed to desires that feed

On fruitage gathered from the tree of life;

To hopes on knowledge and experience built;

Of one in whom persuasion and belief

Had ripened into faith, and faith become

A passionate intuition; whence the Soul,

Though bound to earth by ties of pity and love,

From all injurious servitude was free. (4:1291-98; italics added)

Emerson’s reference in his 1836 note to the “reappearance of his native mountains” suggests his recollection of the final Book of The Excursion, which concludes with a mountain vision, an elevated and affirmative perspective adumbrated by a passage, earlier in this ninth Book, which appealed immensely to Emerson. I mean the Wanderer’s metaphor of advancing age not as a decline, but an ascent—a “final EMINENCE” from which we look down upon the “VALE of years” (9:49-52). Thus “placed by age” upon a solitary height above “the Plain below,” we may find conferred upon us power to commune with the invisible world, “And hear the mighty stream of tendency/ Uttering, for elevation of our thought,/ A clear sonorous voice…” (9:81-92). In his twenties, Emerson endorsed this attitude, that of a “poet represented as listening in pious silence ‘To hear the mighty stream of Tendency’” (JMN 3:80), and in later life he frequently alluded to the passage—once in the immediate aftermath of Waldo’s death—in advocating an elevated, enlarged, more affirmative perspective. Praising “serenity” in his essay on Montaigne,” Emerson again echoes Wordsworth’s Wanderer: “Through the years and the centuries, through evil agents, through toys and atoms, a great and beneficent tendency irresistibly streams” (E&L, 709).

This perspective—optimistic, providential, luminous, and elevated—is reified in the grand sunset viewed by the Wanderer and the “thoughtful few” (9:658), including the Pastor and the Solitary, in the scene toward the conclusion of Book 9. A sunset is seen from a grassy hillside among “scattered groves,/ And mountains bare” (9:505-6). The rays of light, “suddenly diverging from the orb/ Retired behind the mountain-tops,” shot up into the blue firmament in fiery radiance, the clouds “giving back” the bright hues they had “imbibed,” and continued “to receive” (9:592-606). In the shared spectacle of this mountain sunset, the natural Paradise envisaged in one of Emerson’s favorite Wordsworth poems (the “Prospectus” to The Recluse) seems actualized, so that “a willing mind” might almost think,

at this affecting hour,

That paradise, the lost abode of man,

Was raised again, and to a happy few,

In its original beauty, here restored. (9:712-19)

If he is recalling the conclusion of Book 9, Emerson would surely detect Wordsworth’s self-echoing there of the Intimations Ode. The “little band” descends and makes its way in the boat across the lake in falling darkness, no trace remaining of “those celestial splendours ” now “too faint almost for sight” (9: 760, 763; italics added). The Solitary’s parting words, he having “on each bestowed/ A farewell salutation; and the like/ Receiving,” seem casual: “’Another sun,’/ Said he, ‘shall shine upon us, ere we part;/ Another sun, and peradventure more…’” (9:779-80). The Solitary has been gradually converted from a recluse isolated and despairing to one engaged in amity and social responsibility. Even at its most morbid and misanthropic, the Solitary’s conversation had, the Wanderer noted, “caught at every turn/ The colours of the sun” (4:1125-26). Reciprocal salutation and anticipation of “another” and yet another shared “sun,” coming from that “wounded spirit,/Dejected,” indicates the degree of “renovation,” “healing,” and participation in “delightful hopes” (9:771-73, 793) that has been achieved by the end of The Excursion. Appropriately, Wordsworth gives the Solitary words—especially that repeated, hopeful “another…”—that echo the Ode’s hard-earned victory: “Another race hath been, and other palms are won.” Six years after the death of his brother Charles, pitting the latent power of the divinity within him against, and yet in concert with, the impersonal Fate that had just taken from him his precious boy, Waldo, Emerson ends one of his most justly-famous journal entries: “I am Defeated all the time, yet to Victory am I born” (JMN 8:228)

Though that audacity is, of course, a far cry from the acquiescence in the divine Will espoused by Wordsworth’s pious Wanderer, what binds these Romantic strugglers together is their awareness, however affirmative their vision, that life involves loss, misery, pain, and ultimately death. There would be no need to seek so ardently for despair-transforming “hope” if there were not ample cause to despair in the first place. Even “optimism” arises from an agon. “He has seen but half the Universe who never has been shown the house of Pain,” Emerson confided to his aunt while recuperating from tuberculosis in 1827. “Pleasure and peace are but indifferent teachers of what it is life to know.” In his opening words in “Despondency Corrected,” the Wanderer tells the Solitary that he is to find in hope the “one adequate support/ For the calamities of mortal life” (4:10-24). In his essay “Fate,” a more Stoical or proto-Nietzschean Emerson concludes that “Every calamity is a spur and valuable hint,” hints or intimations that “tell as tendency” (E&L 960; italics added). Affirmation and freedom are always under challenge from oppressive forces, ranging from the faculties of “sense” that would dominate imagination and darken the light of all our day, to the distinct yet related loss of “hope” in the state Wordsworth calls Despondency and Coleridge, Dejection. What we require, says the Wanderer, is a faith which, once it becomes a “passionate intuition,” liberates us “From all injurious servitude” (4:1296-98). Among the worse forms of human servitude is despair, the “Despondency” the Wanderer seeks to “correct.” He may not, even by Book 9, have succeeded completely. But the Solitary has come a long way; and that, too, is a victory.

As his 1836 journal-entry confirms, Emerson found solace, even Wordsworth’s “total value,” in the Intimations Ode, in the “blessed consolations in distress” promised in the “Prospectus” to The Recluse, and in the comfort offered by the Wanderer in The Excursion. When a grief-stricken Emerson, devastated by the death of Charles, hoped against hope to “revisit” his own “native mountains that reappear” after we have traversed many a weary mile from our “home,” he thought of the Wanderer and his various doctrines—pantheistic, Stoic, Christian—of all-encompassing hope, at length in Book 4 and, concisely, at the beginning of Book 9. But his mountain-imagery also evokes the mountain sunset toward the end of this final Book of The Excursion. Consoled and “elevated” by the intellectual and emotional companionship of Wordsworthian men able to convert “sorrow” into “delight,” the “palpable oppressions of despair” into the “active Principle” of hope announced by that stoical visionary, the Wanderer, the grieving Emerson saw his own native mountain-tops begin to reappear, to feel again that influx of hope, power, and “glad light” which is, in the familiar line he paraphrases from the Intimations Ode, “the true light of all our day”: a spirituality incarnate in, and indistinguishable from, such self-upholding men, “their spirit” being, as Emerson insists, “the spiritual world” itself (JMN 5:160-61).

As I said at the outset, were there time enough, I would have discussed the two Wordsworth poems Emerson ranked second only to the Ode. Both “Laodamia” and “Dion” are austere, tragic poems that reflect their classical origins, and yet hold out a vestige of consolation, either despite or because of their rather severe Neoplatonism. Emerson coupled “Laodamia” with the Intimations Ode as Wordsworth’s “best” poem on at least two occasions: in an 1868 notebook entry (JMN 16:129) and, six years later, in his Preface to Parnassus, his personal anthology of his favorite poems. If “Laodamia” and “Dion” are less than popular, even, in the case of the latter, barely known to most modern readers, that may be more a comment on the audience than on the artistry of two poems which are at once marmoreal and moving.

Certainly Emerson found them so, placing them just below the great Ode itself, which he considered the age’s supreme exploration not only of that “fountain light of all our day” and “master light of all our seeing,” but of the mysteries of human suffering and mortality. In lines Emerson had by heart, Wordsworth speaks of “truths that wake/ To perish never,” intimations so powerful that nothing, not even “all that is at enmity with joy/ Can utterly abolish or destroy” them. But, as that “utterly” suggests, this is no Pollyanna version of “optimism” The pain registered is real, and that original fontal light is poignantly and irretrievably lost. And yet he insists, as Emerson would after him, that it is “not without hope we suffer and we mourn,” and that implicit in even the most tragic loss there is a stoic and mysteriously spiritual compensation, a denial of grief uttered even as the heart aches:

What though the radiance which was once so bright

SPACEBe now for ever taken from my sight,

SPACESPACEThough nothing can bring back the hour

SPACEOf splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

SPACESPACEWe will grieve not, rather find

SPACESPACEStrength in what remains behind;

SPACESPACEIn the primal sympathy

SPACESPACEWhich having been must ever be;

SPACESPACEIn the soothing thoughts that spring

SPACESPACEOut of human suffering….

—Patrick J. Keane

——————————-

E&L Emerson: Essays and Lecture. Ed. Joel Porte. New York: Library of America, 1983.

JMN The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ed. William H. Gilman, Ralph H. Orth. Et al. 16 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960-82.

L The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson. 10 vols. Ed. Ralph L. Rusk (vols. 1-6), and Eleanor M. Tilton (vols. 7-10). New York: Columbia University Press, 1939, 1995.

TN Topical Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ed. Ralph H. Orth, et al. 3 vols. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990-94.

W The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Centenary Edition. Ed. Edward Waldo Emerson. 22 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1903-04.

For the poems—Emerson: Collected Poems and Translations. Ed. Harold Bloom and Paul Kane. New York: Library of America, 1994; and Wordsworth: The Poems. Ed. John O. Hayden. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

—

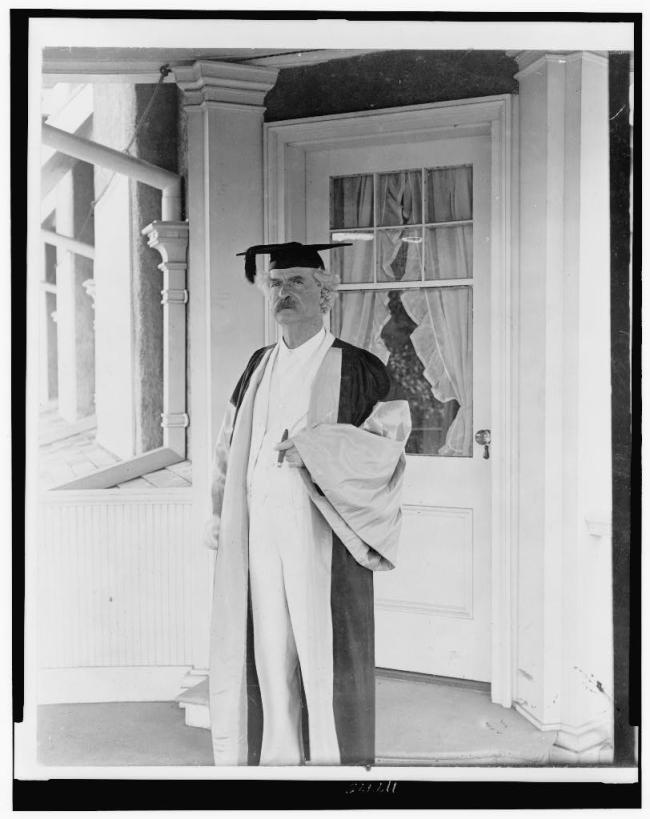

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

Contact: patrickjkeane@old.numerocinqmagazine.com

Robert Day‘

Robert Day‘