Like Paul Curtis, as a young writer I was enthralled by Lawrence Durrell’s four astounding novels — Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive & Clea — together known as The Alexandria Quartet. I can’t count the vivid snippets of scene and dialogue that still float up in my mind: especially the end of Clea when the painter’s wounded hand can suddenly “paint” as here healthy hand had never been able to do or the moment when the feckless journalist (a minor character throughout) returns from war in the desert, a tan, golden warrior who has suddenly found his place in existence. Yes, I love the transformations at the end of the quartet, when time suddenly moves forward. I loved the mysterious and ineffably sad hand prints on the brothel walls, Justine’s mad search for her stolen child, and Pursewarden’s epigrams (I began to learn to write epigrams reading The Alexandria Quartet). There are so many things I tried to copy here as a beginning writer (the faux Einsteinian structure and the Pursewarden endnotes, for example), so many ideals inhaled and transformed to my own uses.

I met Paul M. Curtis during my East Coast reading tour last November and we discovered a bond over beer at the Tide & Boar in Moncton, a bond that included dogs and Durrell. He offers here an all too brief glance backward at the novel of his youth. He began the project half afraid that what he had remembered so passionately might not hold up in the years of wisdom. But his essay sent me back, and when I went to my bookshelves to get the book, I realized my copy was gone, a gift to one of my sons in whom I hope it ignites the same conflagration it did in my heart. And I hope this essay sends our readers to the Quartet as well, an experience you should not miss, the brilliant, elaborate structure, the explosive lava flow of language, the stark view of modern love, the redemption of art.

dg

.

At the time when we knew [Pursewarden] he was reading hardly anything but science. This for some reason annoyed Justine who took him to task for wasting his time in these studies. He defended himself by saying that the Relativity proposition was directly responsible for abstract painting, atonal music, and formless (or at any rate cyclic forms in) literature. Once it was grasped they were understood, too. He added: “In the Space and Time marriage we have the greatest Boy meets Girl story of the age.” (B, 142)[1]

— you might try a four-card trick in the form of a novel, passing a common axis through four stories, say, and dedicating each to one of the four winds of heaven. A continuum, forsooth, embodying not a temps retrouvé but a temps délivré.

Pursewarden to “Brother Ass” (C, 135)

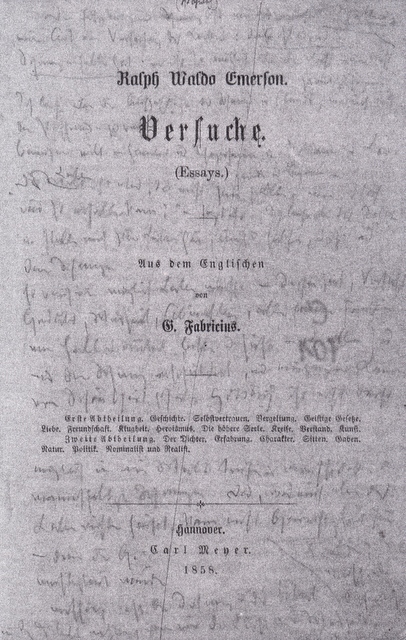

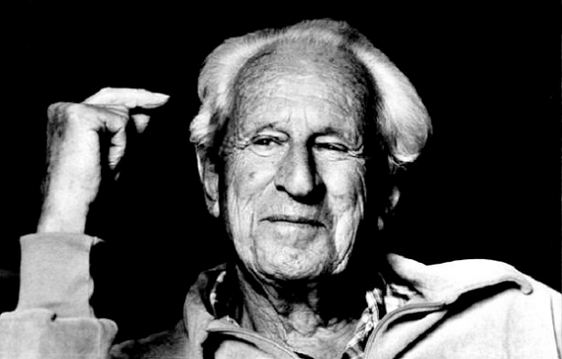

The year 2012 was the centenary of the birth of Lawrence George Durrell, and the event was celebrated with The Guardian’s online reading group of The Alexandria Quartet (1957-60), the publication by Faber of a new edition of the Quartet (with a specially commissioned intro by Jan Morris) and an important conference in London sponsored by the International Lawrence Durrell Society. Durrell was born in Jullundur in the Punjab, India, 27 February 1912, the son of Anglo-Indian parents who had never been to England. The circumstances of Durrell’s birth, while distant from the mother country, pluralized his identity as Anglo-Indian-Irish (Irish on his Mother’s side). Born into colonial exile, the religious and political ideologies of Edwardian England, “Home of the eccentric and the sexually disabled” (M, 85), haunted the young Durrell through his first three novels: Pied Piper of Lovers (1935), Panic Spring (1937) and the The Black Book (1938).[2] Since one is haunted only by what the senses cannot perceive, Durrell had to turn upon his inner self and to exorcise much of his Englishness in order to become an artist. Through the creation of his symbolist künstlerroman, The Black Book, he “first heard the sound of [his] own voice” (Preface, The Black Book, 1960, 13).[3] As a young bohemian in the London of the late 1920’s, Durrell was polymathic in his ambition, a lover of Elizabethan literature, an alluring presence with a powerful sexuality. Yet, he grew into a man of contradictions, best summarized by Marc Alyn:

Here is a recluse who loves being surrounded by people; a hedonist whose great pleasure is asceticism; a lazy man who never stops working; a man who finds joy in despair; a traveller who enjoys nothing more than quiet contemplation; a dandy truly at his ease in the company of tramps and vagrants; a novelist whose major preoccupation is poetry; an enemy of literature who gives the best of himself to his work.[4]

In celebration of the centenary I had the good fortune to embark upon a fresh reading of The Alexandria Quartet with several upper-year undergrads at l’Université de Moncton, and we were joined by several members of Moncton’s very vibrant and bilingual community of readers. Celebration aside, the objective of the reading was to determine if the Quartet still had ‘it’ – the power to hold today’s reader in an intimate and potentially redemptive connection with the work. I remember clearly thirty-two years ago when I read the Quartet, my first contact with Durrell. I spent one uninterrupted week in a glut of reading Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea. The set pieces are unforgettable: the hunt on Lake Mareotis, the Carnival in all its excess, or the Sitna Damiana celebration and the slaughter of the camels in the desert encampment. In the wake of the reading I remember feeling as if I were held in a cocoon of sensation generated by the exoticism of the setting – in particular Alexandria, “the great winepress of love,” “the capital of Memory” (J 14, 188), “the cradle of all our scientific ideas,”[5] “the Alexandria of the human estate” (C, 223) – and being moved equally by the literary ambition of the series. Rarely have I had such an intense reading experience, and I was aware at the time that the originality of the Quartet’s form had marked me as a reader. I was not aware to what extent, however. With the help of our Moncton reader/critics I wanted to determine, in the wake of the Egyptian Spring, if the Quartet would produce a similar effect on first-time readers, and, secondly, to test if the seductions of Durrell’s prose would leave me vulnerable and critically lame as they had the first encounter. As our reading proceeded, the effect on the first-timers was strong and positive, and this in spite of the apparent devaluation of Durrell’s reputation as a late Modernist writer since his death, a confirmed Buddhist, 7 November 1990. From a personal perspective, I came to realize that the Quartet had been my aesthetic standard for the novelistic treatments of time and love, and, even more destabilizing to realize, that this standard had been in silent, unconscious but continuous operation since my first reading. No small claim for one whose job is professing ‘objectively’. Then again, if the Quartet’s “Relativity proposition” holds true, the starting point for every reader, amateur or professional alike, partakes of a relativity particular to each and whose dictates determine each reading.

In celebration of the centenary I had the good fortune to embark upon a fresh reading of The Alexandria Quartet with several upper-year undergrads at l’Université de Moncton, and we were joined by several members of Moncton’s very vibrant and bilingual community of readers. Celebration aside, the objective of the reading was to determine if the Quartet still had ‘it’ – the power to hold today’s reader in an intimate and potentially redemptive connection with the work. I remember clearly thirty-two years ago when I read the Quartet, my first contact with Durrell. I spent one uninterrupted week in a glut of reading Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea. The set pieces are unforgettable: the hunt on Lake Mareotis, the Carnival in all its excess, or the Sitna Damiana celebration and the slaughter of the camels in the desert encampment. In the wake of the reading I remember feeling as if I were held in a cocoon of sensation generated by the exoticism of the setting – in particular Alexandria, “the great winepress of love,” “the capital of Memory” (J 14, 188), “the cradle of all our scientific ideas,”[5] “the Alexandria of the human estate” (C, 223) – and being moved equally by the literary ambition of the series. Rarely have I had such an intense reading experience, and I was aware at the time that the originality of the Quartet’s form had marked me as a reader. I was not aware to what extent, however. With the help of our Moncton reader/critics I wanted to determine, in the wake of the Egyptian Spring, if the Quartet would produce a similar effect on first-time readers, and, secondly, to test if the seductions of Durrell’s prose would leave me vulnerable and critically lame as they had the first encounter. As our reading proceeded, the effect on the first-timers was strong and positive, and this in spite of the apparent devaluation of Durrell’s reputation as a late Modernist writer since his death, a confirmed Buddhist, 7 November 1990. From a personal perspective, I came to realize that the Quartet had been my aesthetic standard for the novelistic treatments of time and love, and, even more destabilizing to realize, that this standard had been in silent, unconscious but continuous operation since my first reading. No small claim for one whose job is professing ‘objectively’. Then again, if the Quartet’s “Relativity proposition” holds true, the starting point for every reader, amateur or professional alike, partakes of a relativity particular to each and whose dictates determine each reading.

The scope of the novel is grand with various settings in Alexandria, Cairo and an unnamed island in the Cyclades. The novel begins with the Englishman Darley’s arrival in Alexandria in 1933 and concludes in 1945 after his second stay there through the war.[6] The grandness of the setting, however, is little compared to Durrell’s ambitions for the form of his novel. Durrell, a poet, novelist, playwright, painter (as ‘Oscar Epfs’) and a playful philosopher (an Epfsistentialist!), is everywhere concerned with form. As laid out in his important Preface to Balthazar, the second volume, he wanted to write “a four-decker novel whose form is based on the relativity proposition.” Durrell later called this ambition pompous presumably because the link to early Twentieth-Century physics is tenuous. I remember one waggish critic commenting that surely one couldn’t fly to Mars after reading the Quartet. Durrell later explained that he wanted to create a bridge between Einstein and Freud, whom he cites in the first epigraph to Justine. The young and aspiring writer Darley is the first-person narrator of the eponymous Justine. The narrative point of view is crucial here because Darley narrates his love affairs first with Melissa, a tubercular dance-hall girl of serene resiliency, and then concurrently with Justine, the deeply flawed mythical figure who is also a powerful and power-hungry Alexandrian Jewess. “When it comes to men who genuinely like women,” Durrell once observed, “each of them is quite simply a mythical being” (Conversations, 30). Melissa is described as “washed up like a half-drowned bird … with her sex broken” (J, 24). However powerless Melissa might be over her life and lovers, the acceptance of her solitude transforms her into a powerful force of agape.[7] Justine’s mythical being, by contrast, is aligned with beauty and a death-dealing political power. She has “the austere mindless primitive face of Aphrodite” (J, 109) — divine beauty, yes, but beauty unblemished by a conscience. Whereas Melissa’s presence is positive and loving, Justine’s influence is “death-propelled” (M, 197), hence thanatic. “[Justine] was not really human – nobody wholly dedicated to the ego is” (J, 203).

The scope of the novel is grand with various settings in Alexandria, Cairo and an unnamed island in the Cyclades. The novel begins with the Englishman Darley’s arrival in Alexandria in 1933 and concludes in 1945 after his second stay there through the war.[6] The grandness of the setting, however, is little compared to Durrell’s ambitions for the form of his novel. Durrell, a poet, novelist, playwright, painter (as ‘Oscar Epfs’) and a playful philosopher (an Epfsistentialist!), is everywhere concerned with form. As laid out in his important Preface to Balthazar, the second volume, he wanted to write “a four-decker novel whose form is based on the relativity proposition.” Durrell later called this ambition pompous presumably because the link to early Twentieth-Century physics is tenuous. I remember one waggish critic commenting that surely one couldn’t fly to Mars after reading the Quartet. Durrell later explained that he wanted to create a bridge between Einstein and Freud, whom he cites in the first epigraph to Justine. The young and aspiring writer Darley is the first-person narrator of the eponymous Justine. The narrative point of view is crucial here because Darley narrates his love affairs first with Melissa, a tubercular dance-hall girl of serene resiliency, and then concurrently with Justine, the deeply flawed mythical figure who is also a powerful and power-hungry Alexandrian Jewess. “When it comes to men who genuinely like women,” Durrell once observed, “each of them is quite simply a mythical being” (Conversations, 30). Melissa is described as “washed up like a half-drowned bird … with her sex broken” (J, 24). However powerless Melissa might be over her life and lovers, the acceptance of her solitude transforms her into a powerful force of agape.[7] Justine’s mythical being, by contrast, is aligned with beauty and a death-dealing political power. She has “the austere mindless primitive face of Aphrodite” (J, 109) — divine beauty, yes, but beauty unblemished by a conscience. Whereas Melissa’s presence is positive and loving, Justine’s influence is “death-propelled” (M, 197), hence thanatic. “[Justine] was not really human – nobody wholly dedicated to the ego is” (J, 203).

At the conclusion of the first volume, Justine disappears and Darley retreats to an island in the Cyclades to lick his love wounds. Once there, he writes an MS which becomes, metafictionally, the novel Justine, the first novel of the Quartet. The Balthazar of the second volume is a homosexual Alexandrian doctor and cabalist who lives and works at the centre of the novel’s ex-pat society. In Balthazar, related again from Darley’s point of view, Durrell creates the device of the “great interlinear” (B, 21), a massive and detailed commentary written by Balthazar on what must be Darley’s MS of Justine. The genius of Durrell’s technique is to relativize – or, better still, recreate — the events of the first novel through the device of Balthazar’s interlinear. Balthazar has an eye for association and the logic of continuum over that of sequence: “But I love to feel events overlapping each other, crawling over one another like wet crabs in a basket” (B, 125). From Balthazar’s interlinear the reader infers that her task is doubled: one should read between the lines of both Balthazar and the Justine it destabilizes. As Darley comes to realize that Justine has used him for political ends and that she loves the other older writer Ludwig Pursewarden, the reader shares his deception with an ontological frisson.

At the conclusion of the first volume, Justine disappears and Darley retreats to an island in the Cyclades to lick his love wounds. Once there, he writes an MS which becomes, metafictionally, the novel Justine, the first novel of the Quartet. The Balthazar of the second volume is a homosexual Alexandrian doctor and cabalist who lives and works at the centre of the novel’s ex-pat society. In Balthazar, related again from Darley’s point of view, Durrell creates the device of the “great interlinear” (B, 21), a massive and detailed commentary written by Balthazar on what must be Darley’s MS of Justine. The genius of Durrell’s technique is to relativize – or, better still, recreate — the events of the first novel through the device of Balthazar’s interlinear. Balthazar has an eye for association and the logic of continuum over that of sequence: “But I love to feel events overlapping each other, crawling over one another like wet crabs in a basket” (B, 125). From Balthazar’s interlinear the reader infers that her task is doubled: one should read between the lines of both Balthazar and the Justine it destabilizes. As Darley comes to realize that Justine has used him for political ends and that she loves the other older writer Ludwig Pursewarden, the reader shares his deception with an ontological frisson.

But the relativism continues with Mountolive. The third novel is remarkable for the political overlay it provides to the previous two, and especially because its apparently banal naturalistic technique is held in sharp contrast to the inventiveness of its content. Durrell called Mountolive the “clou”[8] of the series, and in it he re-shuffles the “four-decker” yet again. Within the omniscient third-person narrative technique, Darley becomes an objective character, much as he thought the others had been from his first-person perspective in Justine and Balthazar. Pursewarden, the political officer serving Ambassador David Mountolive, gets caught in the knot of plot and takes his own life, but not before he has revealed the cause of his deception by writing a message on a mirror. The message is the political and symbolic crux of the novel: politically, because it reveals Pursewarden’s unwitting self-deception with regard to Justine’s “Faustian compact” (M, 201) on behalf of the nascent Jewish state; symbolically, because the surface of this mirror reveals for once its depths that have been hidden in plain sight. As implied within Keats’ famous epitaph, “Here lies One / Whose Name was writ in Water,” the careful reader has a momentary and awful glimpse of the depths below the surface of reality that, to the more casual, has always seemed to be everywhere intact, constant, reliable. As we read very early on in Justine, “Our common actions in reality are simply the sackcloth covering which hides the cloth-of-gold — the meaning of the pattern.” Once we catch a glimpse of this meaning, we behold what Durrell has called the Heraldic Universe, the natural home of the imagination from where it makes “‘sudden raids on the inarticulate’” (Conversations, 136).

But the relativism continues with Mountolive. The third novel is remarkable for the political overlay it provides to the previous two, and especially because its apparently banal naturalistic technique is held in sharp contrast to the inventiveness of its content. Durrell called Mountolive the “clou”[8] of the series, and in it he re-shuffles the “four-decker” yet again. Within the omniscient third-person narrative technique, Darley becomes an objective character, much as he thought the others had been from his first-person perspective in Justine and Balthazar. Pursewarden, the political officer serving Ambassador David Mountolive, gets caught in the knot of plot and takes his own life, but not before he has revealed the cause of his deception by writing a message on a mirror. The message is the political and symbolic crux of the novel: politically, because it reveals Pursewarden’s unwitting self-deception with regard to Justine’s “Faustian compact” (M, 201) on behalf of the nascent Jewish state; symbolically, because the surface of this mirror reveals for once its depths that have been hidden in plain sight. As implied within Keats’ famous epitaph, “Here lies One / Whose Name was writ in Water,” the careful reader has a momentary and awful glimpse of the depths below the surface of reality that, to the more casual, has always seemed to be everywhere intact, constant, reliable. As we read very early on in Justine, “Our common actions in reality are simply the sackcloth covering which hides the cloth-of-gold — the meaning of the pattern.” Once we catch a glimpse of this meaning, we behold what Durrell has called the Heraldic Universe, the natural home of the imagination from where it makes “‘sudden raids on the inarticulate’” (Conversations, 136).

The first three novels are “siblings,” as Durrell explains in the note to Balthazar, “and are not linked in a serial form. They interlap, interweave, in a purely spatial relation. Time is stayed. The fourth part alone will represent time and be a true sequel.”

You see, Justine is written by Darley. It’s his autobiography. The second volume, Balthazar, is Darley’s autobiography corrected or revised by Balthazar. In Mountolive, written by me, Darley is an object in the outside world. Clea would be the new autobiography of Darley some years later, in Alexandria once again (Conversations, 41).

In Clea, the maturer Darley returns to Alexandria now engulfed by the Second World War. The Vichy frigates, “symbolising the western consciousness” (B, 105), lie under arrest at anchor in the harbour; the crew members, however, have the permission to carry small arms. The blonde blue-eyed painter Clea, modelled after Durrell’s third wife, the Alexandrian Claude-Marie Forde, has a significant presence in all three previous novels. Like Darley, she too is an artist evermore about to be, and she paints the portraits of several characters including that of Justine, with whom she had an affair. The tetralogy holds forth the promise of redemption by means of Clea’s transformation into the artist at the novel’s conclusion. Only art has the power to free humanity from its own perversions, eminently the case in Alexandria before a world run riot with fascist ego. In Clea’s apartment, defenceless against a night-time bombing raid, she and Darley become lovers. However genuine their love might be, it comes from a mismatched readiness and founders temporarily. Their love succeeds ultimately, however, through Darley’s newfound “willpower of desirelessness” (Conversations, 119), the Taoist posture from which one respects, contemplates and yet engages Nature.

In Clea, the maturer Darley returns to Alexandria now engulfed by the Second World War. The Vichy frigates, “symbolising the western consciousness” (B, 105), lie under arrest at anchor in the harbour; the crew members, however, have the permission to carry small arms. The blonde blue-eyed painter Clea, modelled after Durrell’s third wife, the Alexandrian Claude-Marie Forde, has a significant presence in all three previous novels. Like Darley, she too is an artist evermore about to be, and she paints the portraits of several characters including that of Justine, with whom she had an affair. The tetralogy holds forth the promise of redemption by means of Clea’s transformation into the artist at the novel’s conclusion. Only art has the power to free humanity from its own perversions, eminently the case in Alexandria before a world run riot with fascist ego. In Clea’s apartment, defenceless against a night-time bombing raid, she and Darley become lovers. However genuine their love might be, it comes from a mismatched readiness and founders temporarily. Their love succeeds ultimately, however, through Darley’s newfound “willpower of desirelessness” (Conversations, 119), the Taoist posture from which one respects, contemplates and yet engages Nature.

When you read Clea I hope you will feel that Darley was necessarily as he was in Justine because the whole business of the four books, apart from other things, shows the way an artist grows up…. I wanted to show, in the floundering Darley, how an artist may have first-class equipment and still not be one.[9]

Before Clea realizes herself as an artist at the novel’s conclusion, Durrell creates a remarkable parable of rebirth. The scene takes place in an underwater gallery off the legendary islet of Timonium, where, in the ruins of their world well lost, Antony and Cleopatra fled after Actium (C, 227). Clea’s right wrist, her brush hand, is pinned underwater accidentally. Darley must deform the hand to release her and to regain the surface. In a life-saving act of resuscitation that is the simulacrum of love-making, the forces of eros and thanatos are held in momentary equilibrium over the unconscious Clea before she splutters back to consciousness and, subsequently, to her new life as artist.

The second epigraph to this essay occurs in the second chapter of the second Book of Clea,[10] and appears in Pursewarden’s diary entitled “My Conversation with Brother Ass.” His imagined interlocutor is Darley. In addition to being the Quartet’s foremost novelist, Pursewarden serves as Durrell’s artistic consciousness of the series. On Pursewarden as character, Durrell observes teasingly, “You must become a Knowbody before you become a Sunbody” (Conversations, 73). Pursewarden knows the difficult lessons of love, even incestuous love, and his ribald wit shines through the entire novel. The reader’s reflex is to give weight to everything he says since he, in effect, compels it. “We live,” he declaims early on in Balthazar, “lives based upon selected fictions. Our view of reality is conditioned by our position in space and time – not by our personalities as we like to think” (B, 14). Pursewarden is the first to articulate the fiction of personality and, in particular, the danger posed by the ego. “My Conversation” is the greatest concentration of Pursewardian apothegms that “litter” the novel,[11] and it’s addressed to the Darley of his imagination, or “Brother Ass,” the aspiring author in the Quartet and the ‘author’ of the first-person ‘autobiographies’ Justine, Balthazar and Clea. Darley reads the conversation in the MS after Pursewarden has taken his own life, ostensibly for a diplomatic gaffe with international reverb. With a wink at the forthcoming literary post-modernism, Pursewarden describes neatly the sprawling structure of the Quartet from within its fourth and final volume. Such a metafictional irony enhances Durrell’s interest in the relativity proposition as he set out in the forward to Balthazar. Unwise as it is to trust any author’s self-evaluation, the four-decker novel is the Quartet’s principle conceit, and it arranges across the four novels, as we shall, see several “moments of connected recollection.”[12] Darley’s attempt at reading the past in order to understand his love for Justine and Melissa is ‘true’, however subjectively. What Darley doesn’t realize in the first two novels is that he cannot escape his own subjectivity in a multi-dimensional universe. By the time the reader has reached the fourth volume, she has been trained to read retroactively, that is to say, with a forward view of the plot at hand as well as simultaneously of its prior layerings. The overall effect is to hold before the reader’s mind a valence of several stories. More to the point, the book teaches us to look forward to looking back. The overall effect of these alternant plots is to make the reader, this reader at least, think about the Quartet less as a sequence and more as a “word-continuum”(Author’s Note to Clea).[13] The reading experience is quite unlike any other series of novels. As we shall see, each narrative layer contains a purposeful misconception on Durrell’s part. And as each layer dissolves with the information supplied by each succeeding volume, the reader experiences a sudden awareness that is compelling because an event first interpreted innocently must be reinterpreted through the powerful catalysis of each narrative development. Each event in the story is dynamic as if it has a life of its own, the plot of which we discover as we proceed. Each, therefore, has the potential to become an opening into time rather than a reified point in some Freytagian progression. Let us turn to one such example of narrative layering that will serve to illustrate Durrell’s finesse with form.

The first example depends upon the agency of a telescope. The scene occurs in Justine at the summer house of Nessim and Justine Hosnani, and I cite the excerpt at length in the hope that the reader will sense the planes of emotion Durrell evokes and superimposes as the passage proceeds. Darley is anxious that Justine’s infidelity has been discovered by her husband Nessim who is also Darley’s close friend.

This further warning was given point for me by an incident which occurred very shortly afterwards when, in search of a sheet of notepaper on which to write to Melissa, I strayed into Nessim’s little observatory and rummaged about on his desk for when I needed. I happened to notice that the telescope barrel had been canted downwards so that it no longer pointed at the sky but across the dunes towards where the city slumbered in its misty reaches of pearl cloud. This was not unusual, for trying to catch glimpses of the highest minarets as the airs condensed and shifted was a favourite pastime. I sat on the three-legged stool and placed my eye to the eye-piece, to allow the faintly trembling and vibrating image of the landscape to assemble for me. Despite the firm stone base on which the tripod stood the high magnification of the lens and the heat haze between them contributed a feathery vibration to the image which gave the landscape the appearance of breathing softly and irregularly. I was astonished to see – quivering and jumping, yet pin-point clear – the little reed hut where not an hour since Justine and I had been lying in each other’s arms, talking of Pursewarden. A brilliant yellow patch on the dune showed up the cover of a pocket King Lear which I had taken out with me and forgotten to bring back; had the image not trembled so I do not doubt but that I should have been able to read the title on the cover. I stared at this image breathlessly for a long moment and became afraid. It was as if, all of a sudden, in a dark but familiar room one believed was empty a hand had suddenly reached out and placed itself on one’s shoulder. I tiptoed from the observatory with the writing pad and pencil and sat in the armchair looking out at the sea, wondering what I could say to Melissa (J, 168-9).

The passage begins by establishing an earthbound perspective as the perspective descends from sky to minaret to hut, and the agency of the telescope serves to conflate the vision of Nessim and Darley. The telescope’s magnification brings to Darley’s eye the precise scene that it had previously brought to Nessim’s, and with an eerie irony Darley becomes an eyewitness to his own adultery as he rummages about in his host’s private quarters. The lovely personification of the breathing landscape in contrast to Darley’s breathlessness brings to bear the weighty hauntedness of the scene. Seeing through Nessim’s eyes magnifies, of course, Darley’s own blindness vis-à-vis the affair. Such shifting of visual perspectives is the Quartet’s primary motif, and the characters often encounter each other through the beguiling surface of a mirror, at one remove from unmediated vision.[14] Darley’s ostensible reason for his presence in the observatory is for paper to write Melissa, his other lover; but one can’t help but wonder how sincere Darley’s motivation to write her might be if he pursues it in the wake of a beach-hut encounter with Justine. The copy of King Lear is a clever device developed with increasing effectiveness by Durrell in his first three novels. Shakespeare’s play resonates powerfully in this scene more from an ambiguity of symbolic reference than through precise allusion. Does Darley’s revelatory moment of telescopic vision imply Gloucester’s blindness and fall to another beach? Or is the reference more general still, about the power of a genuine love unperceived, as is Cordelia’s by Lear and Melissa’s by Darley? The example is one of Durrell’s painterly touches where an image creates a plane of emotion that haunts a scene rather than appearing in full outline.

The telescope returns in the fourth volume, Clea, but with purposeful differences. The Egyptians have begun to expropriate Nessim’s things in punishment for his political adventurism, and his friends defend him in the interim by buying his possessions. Now Mountolive’s, the telescope re-emerges on the verandah of the British summer legation overlooking the Corniche. Clea, “with time to kill,” sees Mountolive and Liza Pursewarden, the dead writer’s sister (and former lover), opposite the legation walking along the Stanley Bay front:

As I had time to kill I started to fool with the telescope, and idly trained it on the far corner of the bay. It was a blowy day, with high seas running, and the black flags out which signalled dangerous bathing. There were only a few cars about in that end of the town, and hardly anyone on foot. Quite soon I saw the Embassy car come round the corner and stop on the seafront. Liza and David got down and began to walk away from it towards the beach end. It was amazing how clearly I could see them; I had the impression that I could touch them by just putting out a hand. They were arguing furiously, and she had an expression of grief and pain on her face. I increased the magnification until I discovered with a shock that I could literally lip-read their remarks! It was startling, indeed a little frightening. I could not ‘hear’ him because his face was half turned aside, but Liza was looking into my telescope like a giant image on a cinema screen. The wind was blowing her dark hair back in a shock from her temples, and with her sightless eyes she looked like some strange Greek statue come to life (C, 117).

Undoubtedly, Durrell wants the reader to telescope the two scenes across the four-decker novel, and in so doing to see the one through the other. Whereas Darley in Justine is haunted as if by a hand on his shoulder, Clea, in her mind’s eye, extends her hand as if to touch the lovers on the beach. Darley’s ‘blind’ love for Justine re-emerges as Liza’s physical blindness; but, whereas the blind Liza has insight into love, Darley must earn his insight through trial and experience. Such a compression of formal symmetries works with a crisp logic. If Darley can be the eyewitness to his own love affair in Justine, Clea’s view of lovers on another beach seals her own love Darley since, with a curious “optical democracy,”[15] she becomes Darley’s specular and, therefore, full partner. The extension of a telescope from volume one to four promotes the effect of looking forward to looking back and creates the illusion of the suspension of time, what Durrell calls disparagingly, the “Western deity.”[16] It’s as if each of these local smaller stories has a life that takes form within the larger narrative of the Quartet. As Darley considers Balthazar’s interlinear: “It was cross-hatched, crabbed, starred with questions and answers in different-coloured inks, in typescript. It seemed to me then to be somehow symbolic of the very reality we had shared – a palimpsest upon which each of us had left his or individual traces, layer by layer” (B, 21-2). Each reader might enjoy the layers singly or in their shifting ensemble.

If one reads the interviews with Durrell about the time of the publication of the Quartet, Durrell raises constantly the question of form. It must have taken considerable daring or confidence and financial need for Durrell to publish the novels separately since the form of the tetralogy was unalterable once the first came to light.

I suppose (writes Balthazar) that if you wished somehow to incorporate all I am telling you into your own Justine manuscript now, you would find yourself with a curious sort of book — the story would be told, so to speak, in layers. Unwittingly I may have supplied you with a form, something out of the way! Not unlike Pursewarden’s idea of a series of novels with “sliding panels” as he called them. Or else, perhaps, like some medieval palimpsest where different sorts of truth are thrown down one upon the other, the one obliterating or perhaps supplementing another. Industrious monks scraping away an elegy to make room for a verse of Holy Writ (B, 183)!

When one attempts to account for form in a novel, the necessary phrase ‘narrative technique’ might sound commonplace to the ear, especially after the metafictional ironies of Ackroyd, Calvino, Don Coles, and David Foster Wallace, to name but a few. Narrative technique is everywhere apparent in the Quartet because of the overlay of diary, letter, novel within novel, commonplace book, and the “great interlinear” which informs much of Balthazar and Justine. The characters as well have a bit of the artist about them: Clea, Nessim and Pursewarden are painters – the first professional, the latter two amateur. Pursewarden, Arnauti, and Darley are writers – again, the first two professional, the latter coming into being through the story of Quartet. Durrell was very conscious of the difficulties of writing a ‘great’ book in the wake of Proust and Joyce. He chose not to write a novel of temps retrouvé or a roman fleuve. Each novel in the Quartet is a “sibling” hence genetically kin rather than related through, say, religion, philosophy or the logic of cause and effect. The principal beauty of Durrell’s narrative technique lies in its enactment of relativity rather than an invocation of it at one remove by means of description. In a manifestly complicated novel, people and events occupy a single time, often a single moment. Each occupation of the moment creates considerable narrative momentum since we see the same moment repeatedly, but differently with each repetition, the familiar made fresh. As Durrell overlays narrative bits in the Quartet, each bit accrues about it its own story, such as Scobie’s apotheosis from a cross-dressing transvestite and alcoholic to the saintly El Scob with his annual feast day. Each overlay aligns planes of emotion that produce a greater impact in their ensemble than might any incident taken singly. Like Balthazar’s “wet crabs” each incident has a narrative ‘life’ as it expressed through the contact with or awareness of another incident. Examples come to mind such as that of Balthazar’s gold ankh (J, 94), a key he uses to wind his pocket watch and the loss and discovery of which triggers its own narrative. Justine has an eburnine ring (B, 200). During the masked Carnival, when rings or wedding bands serve as signs of identity, Justine gives her ring to a minor character, Toto de Bunuel, so that she might pursue an unknown mission anonymously. Toto, mistaken for Justine, is murdered that very night with her ring on his finger. Upon his return to Alexandria, Darley glimpses Clea for the first time “by chance, not design:”

My heart heeled half-seas over for a moment, for she was sitting where once (that first day) Melissa had been sitting, gazing at a coffee cup with a wry reflective air of amusement, with her hands supporting her chin. The exact station in place and time where I had once found Melissa, and with such difficulty mustered enough courage at last to enter the place and speak to her. It gave me a strange sense of unreality to repeat this forgotten action at such a great remove of time, like unlocking a door which had remained closed and bolted for a generation. Yet it was in truth Clea and not Melissa, and her blonde head was bent with an air of childish concentration over her coffee cup. She was in the act of shaking the dregs three times and emptying them into the saucer to study them as they dried into the contours from which fortune-tellers ‘skry’ — a familiar gesture (C, 76-7).

As Darley’s and the reader’s consciousness of the overlay grow, so does the potential for meaning. The story of Balthazar’s ankh – so redolent with suggestions of time — winds the time of its loss and discovery into a recursive loop. Justine’s ring, exhumed from an ancient tomb, partakes of death and confers it, however unintentionally. Darley’s vision of Clea superimposed upon the memory of Melissa “refund[s] an old love in a new” (C, 112). Melissa is the most vulnerable, marginalized and yet the strongest female in the Quartet, and Clea must be reborn before assuming her nature as artist. As Darley remarks to himself, as if speaking of a grammar of the heart, “And in my own life … the three women who also arranged themselves as if to represent the moods of the great verb, Love: Melissa, Justine and Clea” (C, 177). Enacting the relativity proposition across episodes, then, has everything to do with form. As Balthazar comments, “To intercalate realities is the only way to be faithful to time” (B, 226). Or, in Durrell’s own words:

The root [of the mirror game] is relatively banal like an Agatha Christie novel; but by changing the lighting the reality of the thing is changed. My primary game was to write a Tibetan novel rather than a European novel. I attempted to bring together the four Greek dimensions, which are the basis of our mathematics and the five skandas of Chinese Buddhism. For us the individual consciousness of each person is filtered through five perceptions and notions. I wanted to observe what would become an ordinary novel if one changed the lighting and if individuality became blurred. What seems stable in Mountolive in the Quartet is simply the collection of states that are always in agitation. In Chinese philosophy destiny is not limited to a single life; it is well known that you don’t learn anything in one life (Conversations, 197-8).

An essay such as this is can offer but a glimpse of the Quartet because the novel lends itself to multiple types of reading. We can read it for the exoticism of its setting, for its treatment of modern love and for Durrell’s skills as a literary innovator, “An assassin of polish.”[17] As Durrell himself remarked:

The thing was, I wanted to produce something that would be readable on a superficial level, while at the same time giving he reader—to the extent that he was touched by the more enigmatic aspects—the opportunity to attempt the second layer, and so on …Just like a house-painter; he puts on three, four coats. And then it starts to rain, and you see the second coat coming through. A sort of palimpsest (BS, 66).

Durrell noted often and brilliantly that the English language had only one word for love. “The richest of human experiences is also the most limited in its range of expression. Words kill love as they kill everything else” (M, 48). One paradox of Durrell’s treatment of “modern love” is its power to convince Darley of his own objectivity while he is in the midst of the purest egotism. “For observation throws down a field about the observed person or object” (M, 160). His reading of events, however sincere as a seeker of ‘truth’, is still bound unwittingly by the emotional perspective of the loving, and aching, ‘self’. [18] We learn as we read in Justine, “Egotism is a fortress in which the conscience de soi-même, like a corrosive, eats away everything. True pleasure is in giving surely” (53). The notion of the “impossible ego” (Conversations, 214), moreover, is the thematic bridge between the investigation into modern love with the birth of Darley and Clea as artists. Darley discovers his truer expanded self by letting go of his ego and by letting go of Clea and his love for her at the end of the fourth volume. The letting go of his love, and Clea’s intuitive acceptance of the gesture, serves in part to transform both Darley and Clea into artists. Such a pleasure in loving without attachment is the novel’s concluding redemptive moment.

In the investigation, the selfishness of modern love is so necessary, because through the narcissism one comes to the poetic realization and at the end they (Clea and Darley) are both fit to marry each other, so to speak. They have evaluated sexuality and attachment as its true function and they use it in the most spiritual way possible, because it’s information, it’s the algebra of love they’ve discovered” (Conversations, 243).

Durrell’s insistence on the spirituality of their love explains his choice of De Sade for the epigraphs of each novel. De Sade is as “infantile as modern man is: cruel, hysterical, stupid, and destructive – just like us all. [De Sade] is our spiritual malady personified.” [19] In order to release the love and the art within, one must conquer the ego in a Taoist sense. Another contemporary novelist obsessed with form is David Foster Wallace. In reference to the writer’s attitude to her work, he once commented, “The obvious fact that the kids [young writers of the 1990’s] don’t Want to Write so much as Want to Be Writers makes their letters so depressing.”[20] The phrase ‘Want to Be Writers’, in effect, erects statues in honour of and submission to the demands of the ego. The second ‘Want to Write’ presupposes an ‘I’ who creates from beyond the bounds of ego, as did Blake, so as not to be enslaved by the creations of another man. The Quartet concludes in a position of spiritual equilibrium. Clea and Darley are in love but are not together. Their love exists all the more powerfully in the egoless plenitude of its possibility. The “nudge” from the universe felt by Darley at the novel’s last page prompts him to begin a story with the words “Once upon a time.” The time has come for Darley to write from a posture of serenity, of actionless action. To those few artists who can perceive with the Taoist smile in their mind’s eye, such a cosmic nudge is nevertheless the most furtive and yet the most enduring.

To the lucky now who have lovers or friends,

Who move to their sweet undiscovered ends,

Or whom the great conspiracy deceives,

I wish these whirling autumn leaves:

Promontories splashed by the salty sea,

Groaned on in darkness by the tram

To horizons of love or good luck or more love –

As for me now I move

Through many negatives to what I am.[21]

—Paul M. Curtis

——

Bibliography

Alyn, Marc. The Big Supposer: A Dialogue with Marc Alyn. Trans. Francine Barker. London: Abelard-Scuman, 1973.

Durrell, Lawrence. A Smile in the Mind’s Eye. London: Wildwood House, 1980.

_______________. The Alexandria Quartet. 4 vols. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1961.

_______________. Collected Poems: 1931-1974. Ed. James A. Brigham. New York: Viking Press, 1980.

Haag, Michael. “Only the City Is Real: Lawrence Durrell’s Journey to Alexandria.” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, No. 26, Wanderlust: Travel Literature of Egypt and the Middle East(2006): 39-47.

Hitchens, Christopher. Arguably. Signal/McClelland & Stewart, 2011.

Ingersoll, Earl G. Ed. Conversations. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998.

Kaczvinsky, Donald P. “When Was Darley in Alexandria? A Chronology for The Alexandria Quartet.” Journal of Modern Literature Vol. 17 No. 4 (Spring, 1991): 591-594.

MacNiven, Ian A. “Lawrence George Durrell.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online (http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/39830). 11 July 2012.

______________. Lawrence Durrell: A Biography. London: Faber & Faber, 1998.

Max, D. T. Every Love Story is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace. New York: Viking, 2012.

McCarthy, Cormac. Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West. New York: Vintage International, 1992.

Morrison, Ray. A Smile in his Mind’s Eye: A Study of the Early Works of Lawrence Durrell (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005.

____________. “Mirrors and the Heraldic Universe in Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet.” Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 33 No. 4 (Winter, 1987): 499-514.

Wedin, Warren. “The Artist as Narrator in The Alexandria Quartet.” Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 18 No. 3 (July, 1972): 175-180.

Wood, Michael. “Sink or Skim.” London Review of Books Vol. 31 No 1, 1 January 2009. http://www.lrb.co.uk/v31/n01/michael-wood/sink-or-skim

Paul M. Curtis is Director of the English Department at l’Université de Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada, where he has taught English Language and Literature since 1990. He has published numerous articles on the poetry and prose of Lord Byron. Professor Curtis is preparing the first digital scholarly edition of Byron’s correspondence.

m

m

m

- All citations are from The Alexandria Quartet, 4 vols. (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1961) and are indicated by the initial of the volume: J, B, M, C and page number.↵

- Thanks to ECW Press at the University of Victoria, the first two novels have been recently republished. In the The Black Book, the protagonist Lawrence Lucifer transforms himself into an artist by liberating himself from the mind-forg’d manacles of England’s manufacture. Ray Morrison, in his A Smile in his Mind’s Eye: A Study of the Early Works of Lawrence Durrell (Toronto: U of T Press, 2005), is the only critic who has come to terms with the LGD’s debt to Taoism.↵

- Quoted in Ian MacNiven’s biographical article in the ODNB: http://www.oxforddnb.com/templates/article.jsp?articleid=39830↵

- The Big Supposer: A Dialogue with Marc Alyn, trans. Francine Barker (London: Abelard-Scuman, 1973) 11.↵

- Conversations, ed. Earl G. Ingersoll (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998) 207. Hereafter Conversations followed by page number. This collection of interviews is essential reading.↵

- On the chronology of the novel see, Donald P. Kaczvinsky’s “When Was Darley in Alexandria? A Chronology for The Alexandria Quartet,” Journal of Modern Literature Vol. 17 No. 4 (Spring, 1991): 591-594.↵

- “Monsieur, je suis devenue la solitude même. ”Melissa to Pursewarden as they dance (M, 168).↵

- Ian A. MacNiven, Lawrence Durrell: A Biography (London: Faber & Faber, 1998) 466.↵

- Quoted in Warren Wedin, “The Artist as Narrator in The Alexandria Quartet,” Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 18 No. 3 (July, 1972): 175.↵

- My attention to the detail of narrative divisions in the AQ is out of respect to LGD’s formal intentions. If one were to cast her eye over the entire tetralogy and divide each novel into its sub-headings of numerical division, book or chapter number, and then calculate the number of pages contained in each book’s smallest division, the reader would begin to get the impression of the formal (a)symmetries and narrative rhythms that LGD exploits.↵

- Michael Wood, “Sink or Skim,” London Review of Books Vol. 31 No 1, 1 January 2009. http://www.lrb.co.uk/v31/n01/michael-wood/sink-or-skim↵

- To pilfer one of Christopher Hitchens’ phrases, see the essay “Rebecca West: Things worth Fighting For,” [2007] in his collection, Arguably (Signal/McClelland & Stewart, 2011) 194.↵

- See Conversations, “If you remember scenes or characters and can’t quite remember which book they come in, it proves that the four are one work tightly woven, doesn’t it? The joiner is the reader, the continuum is his private property. One dimension in light of the other.” (71).↵

- As Ray Morrison informs us, mirrors occur 120 times in the AQ. “Mirrors and the Heraldic Universe in Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet,” Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 33 No. 4 (Winter, 1987): 499-514.↵

- This brilliant phrase is original to Cormac McCarthy in his Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West (New York: Vintage International, 1992) 247.↵

- Durrell’s notebook “A Cosmography of the Womb, London Jan 1939,” is quoted in Michael Haag’s “Only the City Is Real: Lawrence Durrell’s Journey to Alexandria,” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, No. 26, Wanderlust: Travel Literature of Egypt and the Middle East(2006): 42.↵

- “Style,” Collected Poems: 1931-1974, ed. James A. Brigham (New York: Viking Press, 1980) 243-4.↵

- “Then in the relativity field you get the relation of subject and object completely changed. In other words you can’t look at a field without influencing it. A very singular thing” (Conversations, 121).↵

- MacNiven, Lawrence Durrell, 433.↵

- See the first full-length biography on DFW by D. T. Max, Every Love Story is a Ghost Story (New York: Viking, 2012) 178.↵

- “Alexandria,” Collected Poems, 154, lines 1-9.↵

Robert Day‘

Robert Day‘

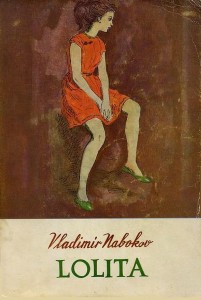

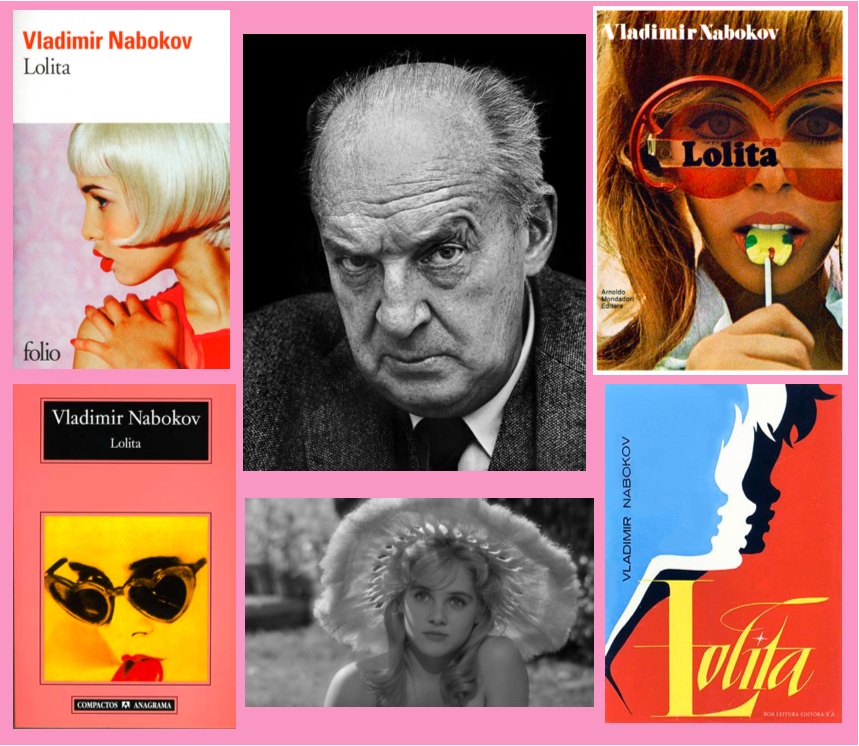

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.

From the Stanley Kubrick film Lolita.