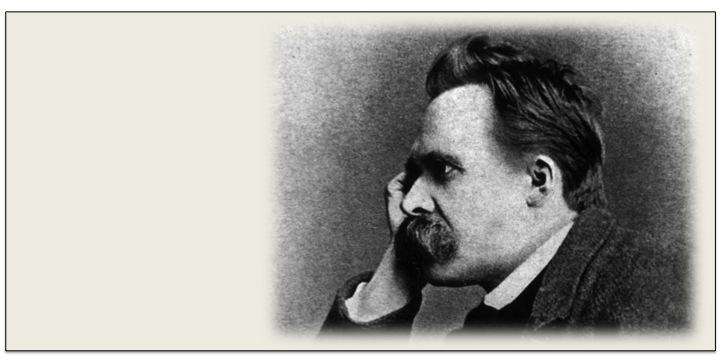

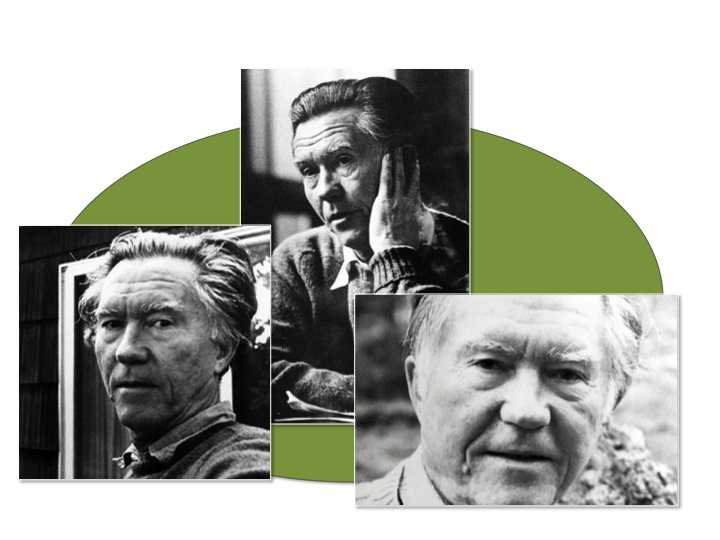

Yeats, 1932 by Pirie MacDonald

Yeats, 1932 by Pirie MacDonald

.

Does the imagination dwell the most

Upon a woman won or woman lost?

If on the lost, admit you turned aside

From a great labyrinth….(“The Tower,” II)

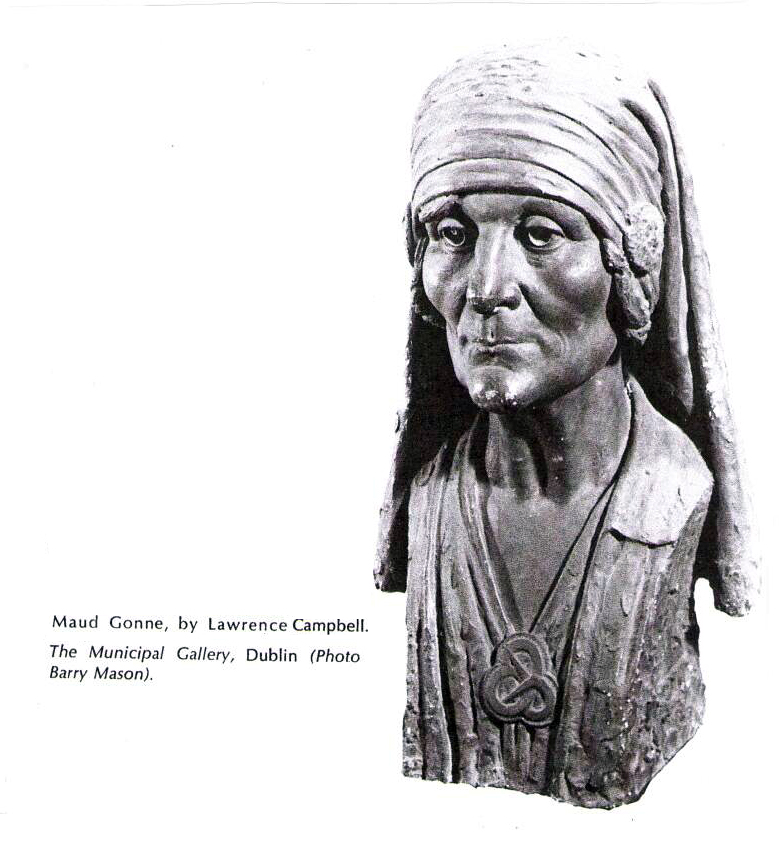

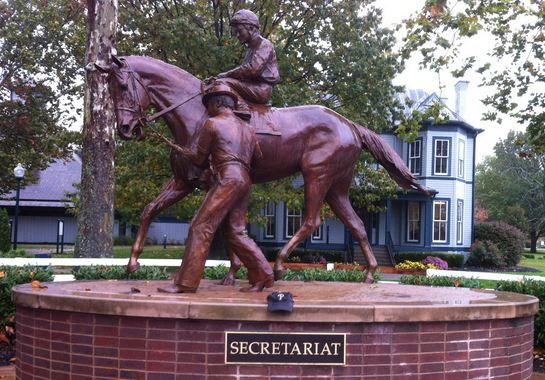

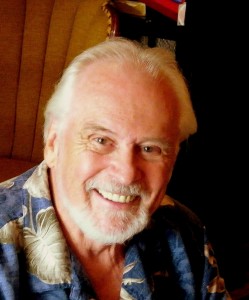

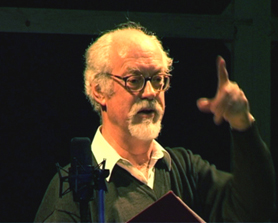

The genesis of this essay was a talk I was invited to give as part of Le Moyne College’s commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the birth of W. B. Yeats. I’d been asked to say a few words, in the Bernat Special Events Room of the Library, about three of the books to be displayed, and then, widening the gyre, to try to present what I took to be the “quintessential” Yeats: the Identity of the Man beneath the many Masks (to fuse the titles of Richard Ellmann’s two pioneering Yeats studies). To prepare for the next event in our anniversary celebration (the Curlew Theatre production, The Muse & Mr. Yeats), I was also asked to recite some poems to and about his principal Muse, the improbably beautiful and never fully-attainable Maud Gonne. She is the “woman lost,” the “great labyrinth” that fascinated Yeats and from which, he admits in the surprising lines cited in my epigraph, he somehow “turned aside.” I’ll return to this point.

Of the three first editions I discussed, the first was my copy of the pamphlet, On the Boiler (1939). The other two are rare volumes: my signed copies of the Fountain Press edition of The Winding Stair (1929), and of the Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats (1957). What follows begins with, but goes far beyond, what I said in the library, though I’ve retained some of the talk’s casual tone. Taking advantage of the essay format, I’ve added many poems to those I quoted in the library, most related to Maud Gonne. That is true even of the major poem on which (to borrow Soul’s language) I have most “fixed” my “attention”: “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” the dominant poem in both versions of The Winding Stair. I focus primarily on Self’s life-affirming emblem, the ancestral sword wound in embroidered silk, and on Self’s peroration, affirming that most painful yet “most fecund” experience of Yeats’s life, his unrequited love for Maud Gonne. Finally, here as in the talk, I try, at some risk of “reducing” the poetry to autobiography, to get beneath the various Yeatsian masks in order to reveal, as he himself did in several late poems, the man at his most human, the poet who moves us most.[1]

§

In the final movement of “A Bronze Head” (1938), the last Maud Gonne poem, Yeats seems to use her as his mask, imagining her “supernatural,/ As though a sterner eye looked through her eye/ On this foul world in its decline and fall,/ On gangling stocks grown great, great stocks run dry, / Ancestral pearls all pitched into a sty.” In On the Boiler, also written in 1938, Yeats comments on what he saw as the current decline of European civilization. He had earlier employed female personae, “Crazy Jane” and the “Woman Young and Old,” as masks through which he could speak with remarkable sexual candor. The considerably less appealing mask in On the Boiler is male: the persona of an old seaman (the depiction on the cover is from a design by the poet’s artist-brother, Jack) Yeats once heard ranting from atop a ship’s boiler. Ill, cranky, but energized by what he called (in “An Acre of Grass,” a late fusion of Blake and Nietzsche) “an old man’s frenzy,” Yeats vents some of his least inhibited notions about preserving aristocratic values threatened by cultural, intellectual, and physical “degeneration.”

He had been reading about eugenics, a pseudo-science that infects the final stanza of “A Bronze Head,” as well as “Under Ben Bulben,” too often taken as his last testament (I will conclude by suggesting other candidates for that honor, including Yeats’s own surprising preference). Coupled with the nightmare aspect of Nietzschean Recurrence, eugenics also figures prominently in the remarkable play Purgatory, first published in On the Boiler (along with three previously unpublished poems, one, “Crazy Jane on the Mountain,” featuring the reappearance of his best-known female persona, now commenting on politics). Eugenic theory is most notoriously prevalent in the section of the pamphlet titled “To-morrow’s Revolution,” where Yeats laments biological and cultural “degeneration” and calls for war as a preferable alternative.[2] Though Yeats, a man of the theater after all, is being theatrical, flamboyant, and hyperbolic, there doesn’t seem to be nearly enough daylight between the poet himself and that old seaman ranting from atop the boiler.

But it must be added that Yeats, attracted to Fascism, was repelled by National Socialism. Nor, despite his praise of the most skillful of the German submarine commanders of World War I, could he have foreseen the full horror of the Second World War, let alone the most rancid and horrific fruit of eugenic theory in practice: the genocidal extermination carried out in the Nazi death-camps. Like James Joyce and his own “strong enchanter,” Nietzsche, Yeats was resolutely opposed to anti-Semitism (the same cannot be said of Maud). Like many others, he underestimated the threat presented by Hitler when he first came to power. But, for all his reckless talk about a coming revolution and salvation through destruction, the sole substantive reference he makes to the Führer has to do with cruelty. As he reports in a February 1934 letter to his most intimate correspondent, Olivia Shakespear, Blue Shirt neighbors had put to death a collie Mrs. Yeats believed (mistakenly as it turned out) had eaten her prize white hen. After quoting the neighbor’s brutally brusque response, “have done away with collie-dog,” Yeats comments: “note the Hitler touch.”[3]

§

We can turn now from lesser to greater Yeats and to those two signed editions. In the library talk, I discussed the provenance of both, and, taking up the teaser in the flyer that had been distributed, explained how it was that I came to own a signed copy of a book published in 1957, almost two decades after the poet’s death. It takes no ghost from the grave to explain that posthumous signature. Shortly before he died, Yeats signed 825 sheets to be bound into selected volumes of the long-delayed Edition de Luxe of his complete works, to be published, finally, in 1940. Two events intervened: Yeats died in January 1939, and, eight months later, World War II broke out. The deluxe edition was cancelled, and the signed sheets disappeared. Until they were discovered in a vault in the mid-1950s, just in time to be bound into selected copies of the much-anticipated Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, published eighteen years after his death. Precisely eighteen years after that, I was married, and my best man gave one of these signed copies (No. 49) to my wife Ann and me as a wedding present. That was in 1975. Much has changed since then; but I’ve hung on to the book, which has appreciated tenfold in value from the $300 paid forty years ago.[4]

Yeats’s signature in the Variorum requires no ghostly explanation. But is it true (as the poet prophesied in September 1938) that “Under bare Ben Bulben’s head/ In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid”? I’m no fan of the poem where that dramatic announcement was made, just four months before Yeats died but ten years before his headstone was erected. For decades, “Under Ben Bulben” was printed at the end of the Collected Poems, not Yeats’s intention, as we know from a list he prepared shortly before his death. He meant it to open his final volume, so that everything else in what we know as Last Poems would seem, as it were, spoken from beyond the grave.[5] We should all be loath to accept as Yeats’s final testament a poem whose occasional magnificence is tainted by bombast about “the indomitable Irishry” and Anglo-Irish “Hard-riding country gentlemen” accompanied by a picturesque “peasantry,” not to mention (On the Boiler versified) the eugenic revulsion from “Base-born products of base beds.” And yet the poem rises from its detritus at several points, certainly in the final funereal drumbeat, ending with the “unconventional” and enigmatic epitaph:

Under bare Ben Bulben’s head

In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid,

An ancestor was rector there

Long years ago; a church stands near,

By the road an ancient Cross.

No marble, no conventional phrase,

On limestone quarried near the spot

By his command these words are cut:

…………Cast a cold eye

…………On life, on death.

…………Horseman, pass by!

The famous epitaph should be read, as should most of Yeats, as an interaction with tradition. The epitaph becomes less cryptic when we interpret it as a vital equestrian and notably pagan response to morose admonishments to travelers to stop (Siste, viator) and reflect that, as the dead are, so shall we be. Instead, Yeats’s “unconventional” advice for visitors to his grave is to look on life and death with equanimity, then, energized rather than enervated, to “pass by,” getting on with our own lives. It should be added that “cold” for Yeats is often an exhilarating adjective. He speaks of the “cold and rook-delighting heaven” (“The Cold Heaven”), hopes to someday write a “Poem maybe as cold/ And passionate as the dawn” (“The Fisherman”), and presents the girl in the opening poem of “A Woman Young and Old,” less responsive to ethical demands and village morality than to aesthetic impulses, as thrilled that her young man’s “hair is beautiful,/ Cold as the March wind his eyes.”

The epitaph’s mystery can be illuminated. The mystery still surrounding precisely what is buried beneath it is less easily resolved. The poet died in southern France on January 28, 1939. “He disappeared in the dead of winter,” Auden begins his great elegy “In Memory of W. B. Yeats,” and that wasn’t the end of the disappearances. Yeats was buried in Roquebrune cemetery, near the French-Italian border. When a friend and late lover, Edith Shackleton Heald, who had attended the funeral, visited the cemetery in 1946, the marker was still there. But the following year, when she returned, the marker was gone and she was told that the remains had been moved to a common area. The cemetery records were ambiguous. In September 1948, three years after the war’s end, the poet’s supposed remains were exhumed, shipped to Ireland, and reinterred under the great mountain he had made even more famous. The Sligo Chamber of Commerce, benefiting from the thriving Yeats Industry, doesn’t want to hear about it, but the truth is that we’re not altogether certain what “is laid” under Ben Bulben and beneath that commanding epitaph. One thing that is certain is Yeats’s posthumous literary reputation. Despite shifts in styles and sensibility over the three-quarters of a century since he died, Yeats continues to be generally considered the major poet of the 20th century—“certainly,” as T. S. Eliot said in commemorating his rival in the first Yeats Memorial Lecture, in 1940, “the greatest in this language, and so far as I am able to judge, in any language.”

§

I want now to distinguish the 1929 Fountain Press The Winding Stair from the 1933 Macmillan The Winding Stair and Other Poems, Yeats’s longest volume and, along with The Tower (1928), his greatest. I purchased the Fountain Press edition for $225, after phoning the leading expert in the world, my friend the late George Mills Harper, to confirm my decision. That was in 1979, precisely a half-century after its publication. It’s a slim volume, containing two very short poems (“Death” and “Oil and Blood”) and four major texts, beginning with “In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz,” its beautiful first lines, “The light of evening, Lissadell,/ Great windows open to the south,” establishing the volume’s mixture of elegy and affirmation. Then come “A Dialogue of Self and Soul” and “Blood and the Moon,” and the volume ends with the eleven-poem sequence, “A Woman Young and Old.” Despite the many “other poems” later added, both the 1929 and 1933 volumes begin with an elegy for two women (recalled as “Two girls in silk kimonos, both/ Beautiful”) and end with a concentrically-structured sequence spoken by a woman, its final framing poem an elegy for Antigone.[6]

And that rondure is continued beneath the surface since that concluding elegy, “From the Antigone,” was drafted at the same time as the volume-opening elegy for Eva and Con; we know because the ink has leaked through the manuscript page. As suggested by the titles alone, as well as the omphalos-structure of “A Woman Young and Old,” the 1929 and 1933 editions of The Winding Stair are “female” in orientation, countering the preceding, essentially “masculine” volume The Tower—though the fact that, in Yeats’s actual Norman tower, the inner spiral staircase is, of course, part of a unified structure, suggests that the poetic as well as architectural tower and winding stair are ultimately complementary rather than antithetical. The same is true of the relationship between the sword and the silken embroidery wound about its sheathe in the crucial symbol in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” a poem that figures centrally not only in both editions of The Winding Stair, but in Yeats’s work as a whole.

The “Dialogue” also interacts with the whole canon of Body-Soul “debates.” That tradition, going back to Plato and to Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis (“The Dream of Scipio”), can be traced in Middle- English debate poems and, in the 17th-century, among others, George Herbert’s “The Collar” and Milton’s masque, Comus. Though wit complicates the tension in Marvell’s “A Drop of Dew,” “A Dialogue between the Resolved Soul and Created Pleasure,” and “A Dialogue Between the Soul and Body,” Yeats stands the whole venerable tradition on its head, affirming life and human sexuality in the struggle with soul’s commands and demands. In “Father and Child,” opening the Woman Young and Old sequence concluding both versions of The Winding Stair, Yeats echoes “The Collar” in order to alter it. Herbert’s rebellious speaker, who “struck the board and cried, ‘No more!” grows ever more strident, proclaiming himself to be “free as the wind.”

But as I raved and grew more fierce and wild

…………………….At every word

Methoughts I heard one calling, Childe!,

…………………….And I replied, My Lord.

Whereas the Childe in Herbert’s poem ultimately submits to divine authority, the Yeatsian Child remains quietly defiant, oblivious to Father’s ranting. Unmoved by what troubles him (conventional morality reflected in village gossip), she affirms instead beauty and the dangerous, liberating wind of sexual awakening:

She hears me strike the board and say

That she is under ban

Of all good men and women,

Being mentioned with a man

That has the worst of all bad names,

And thereupon replies,

That his hair is beautiful,

Cold as the March wind his eyes.

The victor in the “debate” between “Father and Child” is clear because Yeats makes it so, the poet in him overcoming his own paternalism (the poem is based on a breakfast-table exchange between Yeats and his daughter Anne, a child he advances to puberty for the song’s sake). We may turn now to the related but more momentous agon between opposites in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul.”

Some critics have thought The Winding Stair a book misleadingly titled. Presumably because, influenced by the Soul’s opening line: “I summon to the winding ancient stair,” they have taken the book’s emphasis to be on the transcendent ascent rather than the cyclical winding. But the “winding stair” of this volume, the spiral staircase within Thoor Ballylee—that “winding, gyring, spiring treadmill of a stair” which Yeats declares, in the opening movement of “Blood and the Moon,” to be his “ancestral stair,” still bearing the “Odour of blood”—is not only, or even primarily, a scala coeli or Jacob’s ladder by which we mount to spiritual vision.[7] Soul would have it so, of course, in “Dialogue”; but the protagonist, the antithetical Self, is not to be bullied into submission. Imperiously commanded to fix his “wandering” attention “upon” spiritual ascent and “ancestral night,” Self remains diverted by the greatest of Yeats’s fused symbols: the “ancient blade” (given Yeats as a gift by a Japanese admirer, Junzo Sato) scabbarded and bound in complementary “female” embroidery. That sheathed and silk-wound sword—“emblems of the day against the tower/ Emblematical of the night,” fusing the sacred and the profane, war and love, the phallic and the vaginal—becomes Yeats’s symbol of gyring life, set against the vertical ascent urged by the Neoplatonic Soul. And the sword’s winding embroidery is associated, as we shall see, with the labyrinthine Maud Gonne.

In the opening movement of the poem, the half in which there is still a semblance of actual dialogue, hectoring Soul repeatedly demands that Self “fix” every thought “upon” the One, “upon” the steep ascent, “upon” the occult Pole Star, “upon” the spiritual quarter where all thought is done. But the recalcitrant Self remains diverted by the Many, by earthly multiplicity, by the sword wound in embroidery replicating the windings of mortal nature. In unpublished notes to the poem, first printed in full in 1987 in my Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition, Yeats describes “Dialogue” as “a variation on Macrobius.” The reference, here as in “Chosen,” is to the Neoplatonist to whose Commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis Yeats had been directed by his friend F. P. Sturm. In Cicero’s text, despite the rhetorical admonition of Scipio’s ghostly ancestor, “Why not fix your attention upon the heavens and contemn what is mortal?” young Scipio admits he “kept turning my eyes back to earth.” According to Macrobius, Scipio “looked about him everywhere with wonder. Hereupon his grandfather’s admonitions recalled him to the upper realms.” Though the agon between the Yeatsian Self and Soul is identical to that between young Scipio and his grandfather’s spirit, the Soul in Yeats’s poem proves to be a considerably less successful spiritual guide than that formidable ghost.

Turning a largely deaf ear to Soul’s advocacy of the upward path, Self (revealingly called “Me” in the drafts of the poem) has preferred to focus downward, on life, brooding on the consecrated blade upon his knees with its tattered but still protective wrapping of “Heart’s purple.” That “flowering, silken, old embroidery, torn/ From some court-lady’s dress and round/ The wooden scabbard bound and wound” makes the double icon “emblematical” not only of “love and war,” but of the ever-circling gyre: the eternal, and archetypally female, spiral. When Soul’s paradoxically physical tongue is turned to stone with the realization that, according to his own austere doctrine, “only the dead can be forgiven,” Self takes over the poem. He goes on to win his way, despite considerable difficulty, to a self-redemptive affirmation of life.

Thoor Ballylee, Yeats’ 14th century Norman tower house.

Thoor Ballylee, Yeats’ 14th century Norman tower house.

Self begins his peroration defiantly: “A living man is blind and drinks his drop./ What matter if the ditches are impure?” This “variation” on Neoplatonism, privileging life’s filthy downflow, or “defluction,” over the Plotinian pure fountain of emanation, is followed by an even more defiant rhetorical question: “What matter if I live it all once more?” “Was that life?” asks Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. “Well then! Once more!” (Zarathustra 3.2). But Self’s grandiose and premature gesture is instantly undercut by the litany of grief that Nietzschean Recurrence, the exact repetition of the events of one’s life, would entail—from the “toil of growing up,” through the “ignominy of boyhood” and the “distress” of “changing into a man,” to the “pain” of the “unfinished man” having to confront “his own clumsiness,” then the “finished man,” old and “among his enemies.” Despite the Self’s bravado, it is in danger of being shaped, deformed, by what Hegel and, later, feminist critics have emphasized as the judgmental Gaze of Others. Soul’s tongue may have turned to stone, but malignant ocular forces have palpable designs upon the assaulted Self:

How in the name of Heaven can he escape

That defiling and disfigured shape

The mirror of malicious eyes

Casts upon his eyes until at last

He thinks that shape must be his shape?

This would be, as Yeats says in “Ancestral Houses” (1921), to lose the ability to “choose whatever shape [one] wills,” and (echoing Browning’s arrogant Duke, who “choose[s] never to stoop”) to “never stoop to a mechanical / Or servile shape, at others’ beck and call”: Yeats’s rejection of “slave morality” in favor of Nietzschean “master morality.” The centrality of “A Dialogue of Self and Soul” is enhanced by its repercussions in his own work and its absorption of so many influences outside the Yeatsian canon. Aside from the Body/Soul debate tradition, and the combat between Neoplatonism and Nietzsche, this Yeatsian psychomachia incorporates, among other poems in the Romantic tradition, another Browning poem, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” and Blake’s feminist Visions of the Daughters of Albion.[8] Self’s eventual victory, like Oothoon’s, is over severe moralism, the reduction of the body to a defiled object. In Yeats’s case it seems, above all, a triumph over his own Neoplatonism or Gnosticism: an instance of Nietzschean Selbstüberwindung, creative “self-overcoming,” for, as Yeats said, “we make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry” (Mythologies 331).

Since “Dialogue” is a quarrel with himself, the spiritual tradition is not simply dismissed, here any more than in the Crazy Jane or Woman Young and Old sequences. For Yeats, the world of experience, however dark the declivities into which the generated soul may drop, is never utterly divorced from the world of light and grace. The water imagery branching through Self’s peroration subsumes pure fountain and impure ditches. There is a continuum. The Plotinian fountain cascades down from the divine One through mind or intellect (nous) to the lower depths. As long, says Plotinus, as nous maintains its gaze on and contemplation of God (the First Cause or “Father”), it retains the likeness of its Creator (Enneads 5.2.4). But, writes Macrobius (Commentary 1.14.4), the soul, “by diverting its attention more and more, though itself incorporeal, degenerates into the fabric of bodies.”

Viewed from Soul’s perspective, Self is a falling off from the higher Soul. When the attention, supposed to be fixed on things above, is diverted below—down to the blade on his knees wound in tattered silk and, further downward, to life’s “impure” ditches—the Self has indeed degenerated into the “fabric,” the tattered embroidery, of bodies. And yet, as usual in later Yeats, that degradation is also a triumph, couched in terms modulating from stoic contentment to fierce embrace:

I am content to live it all again

And yet again, if it be life to pitch

Into the frog-spawn of a blind man’s ditch,

A blind man battering blind men;

Or into that most fecund ditch of all,

The folly that man does

Or must suffer, if he woos

A proud woman not kindred of his soul.

I am content to follow to its source

Every event in action or in thought;

Measure the lot, forgive myself the lot!

When such as I cast out remorse

So great a sweetness flows into the breast

We must laugh and we must sing,

We are blest by everything,

Everything we look upon is blest.

Following everything to the “source” within, Self spurns Soul’s tongue-numbing doctrine that “only the dead can be forgiven.” Instead, having pitched with vitalistic relish into life’s filthy frog-spawn, Self audaciously (or blasphemously) claims the power to forgive himself. In a similar act of self-determination, Self “cast[s] out” remorse, reversing the defiling image earlier “cast upon” him by the “mirror of malicious eyes.” The sweetness that “flows into” the self-forgiving breast redeems the frog-spawn of the blind man’s ditch and even that “most fecund ditch of all,” the painful but productive folly that is the bitter-sweet fruit of unrequited love. It would violate decorum—and is hardly necessary—for Yeats to name the “proud woman not kindred of his soul,” but I will return to her at the end.

That sweet flow also displaces the infusion (infundere: “to pour in”) of Christian grace through divine forgiveness. It is a claim to autonomy at once redemptive and heretical, and a masterly fusion of Yeats’s two principal precursors. “Nietzsche completes Blake, and has the same roots,” Yeats claimed. If, as he also rightly said, Blake’s central doctrine is a Christ-like “forgiveness of sins,” the sweetness that flows into the suffering but self-forgiving “breast,” the breast in which Blake also said “all deities reside,” allies the Romantic poet with Nietzsche. He had been preceded by the German Inner Light theologians, but it took Nietzsche, the son of a Protestant minister, to most radically transvalue the Augustinian doctrine that man can only be redeemed by divine power and grace, a foretaste of predestination made even more uncompromising in the strict Protestant doctrine of the salvation of the Elect as an unmerited gift of God. One must find one’s own “grace,” countered Nietzsche in Daybreak, a book read by Yeats. He who has “definitively conquered himself, henceforth regards it as his own privilege to punish himself, to pardon himself”—in Yeats’s phrase, “forgive myself the lot.” We must cast out remorse and cease to despise ourselves: “Then you will no longer have any need of your god, and the whole drama of Fall and Redemption will be played out to the end in you yourselves!” (Nietzsche, Daybreak §437, §79)

In 1902, enthralled by his “excited” reading of “that strong enchanter,” Yeats drew in the margin of a Nietzsche anthology a diagram crucial to understanding much if not all of his subsequent thought and work. He grouped under the heading NIGHT: “Socrates, Christ,” and “one god”— “denial of self, the soul turned toward spirit seeking knowledge.” And, under the heading DAY: “Homer” and “many gods”—“affirmation of self, the soul turned from spirit to be its mask & instrument when it seeks life.”[9] That diagrammatical skeleton, anticipated by the pull between eternity and the temporal in such early poems as the crucial “To the Rose upon the Rood of Time” (1892), is later fully fleshed out by Yeats’s own chosen exemplar in “Vacillation” (1932)—“Homer is my example and his unchristened heart”—and Self’s choice of Sato’s sword wound in “Heart’s purple,” flowers “from I know not what embroidery”: “all these I set/ For emblems of the day against the tower/ Emblematical of the night.” While Yeats could never bring himself to endorse Nietzschean atheism, the final chant of Self in “Dialogue”—“We must laugh and we must sing/ We are blest by everything,/ Everything we look upon is blest”—is clearly the product of Yeats’s brilliant in-gathering of Nietzsche and Blake, whose Oothoon cries out climactically, “sing your infant joy!/ Arise and drink your bliss, for every thing that lives is holy!” To be sure, Self’s final lines are riddled with other echoes.[10] But the critical figures remain Blake and Nietzsche. It is under their twin auspices, as manipulated by Yeats, that Self finds the bliss traditionally reserved for those who follow the ascending path. Yeats’s alteration of the spiritual tradition completes Blake, who considered cyclicism the ultimate nightmare, with that Nietzsche whose exuberant Zarathustra jumps “with both feet” into “golden-emerald delight”:

In laughter all that is evil comes together, but is pronounced holy and absolved by its own bliss; and if this is my alpha and omega, that all that is heavy and grave should become light, all that is body, dancer, all that is spirit, bird—and verily that is my alpha and omega: oh, how should I not lust after eternity and the nuptial ring of rings, the ring of recurrence? (Thus Spoke Zarathustra 3:16)

We might say that Zarathustra here also “jumps” into a cluster of images and motifs we would call Yeatsian, remembering, along with Self’s laughing, singing self-absolution, “Among School Children,” where “body is not bruised to pleasure soul,” and we no longer “know/ The dancer from the dance”; the natural and golden birds of the Byzantium poems; and the final transfiguration of Yeats’s central hero, both in The Death of Cuchulain and “Cuchulain Comforted,” into a singing bird.

In “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” the Yeatsian-Nietzschean Self, commandeering the spiritual vocabulary Soul would monopolize, affirms eternal recurrence, the labyrinth of human life with all its tangled antinomies of joy and suffering. In subverting the debate-tradition, Yeats leaves Soul with a petrified tongue, and gives Self a final chant that is among the most rhapsodic in that whole tradition of secularized supernaturalism Yeats inherited from the Romantic poets and from Nietzsche. In a related if somewhat lower register, it is also the vision of Crazy Jane and the Woman Young and Old: the female embodiments of the often anguished but ultimately life-affirming vision that dominates, first, The Winding Stair, and then— four years later, when the volume was fleshed out by Words for Music Perhaps, beginning with “Byzantium” and concluding with the Crazy Jane sequence—The Winding Stair and Other Poems.

§

One purpose of the original library talk had been to prepare the audience for a more formal celebratory event: the Curlew Theatre production of The Muse & Mr. Yeats, written and produced by Irish poet Eamon Grennan. I therefore said a few poems I had by heart, centering, inevitably, on the poet’s only-once-named but known-to-all Muse, Maud Gonne—according to George Bernard Shaw, not an easy man to awe, “the most beautiful woman in the British Isles.” I began with an early, mythologically-disguised Maud poem, “The Song of Wandering Aengus,” from The Wind Among the Reeds (1899), originally and reductively titled “A Mad Song,” which at least clarifies the action-initiating “fire” in the speaker’s “head.” The speaker and seeker in this almost miraculously beautiful lyric is the Celtic god of poetry, love, and youth, though here he ages in his eternal quest of the transfigured beauty, palpable but elusive, he had once glimpsed in the evanescent form of one of the shape-changing women of the Celtic Sidhe:

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire aflame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl,

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

That “glimmering girl with apple blossom in her hair,” however magically transformed (even that is connected to Maud by the self-pitying “The Fish,” in this same volume), [11] will remind us that when Yeats first saw Maud, in 1889, “she seemed,” he recorded in 1922, “a classical impersonation of the Spring, the Virgilian commendation ‘She walks like a goddess’ made for her alone. Her complexion was luminous, like that of apple-blossom through which the light falls, and I remember her standing that first day by a great heap of such blossoms in the window.” By then he had described her in a poem, “The Arrow” (1901), as “Tall and noble but with face and bosom/ Delicate in colour as apple blossom.”[12] Nevertheless, the exquisite “Song of Wandering Aengus” is cloaked in mythology. An earlier, even more covert Maud poem, “The Cap and Bells” (1893), was accompanied by an evasive note when it was published in The Wind Among the Reeds. Describing it (as Coleridge had described the genesis of “Kubla Khan”) as coming to him in a dream or vision, Yeats concludes, “The poem has always meant a great deal to me, though as is the way with symbolic poems, it has not always meant quite the same thing. Blake would have said, ‘The authors are in eternity,’ and I am quite sure they can only be questioned in dreams.”[13]

He had reason to deflect the curious. For him, “The Cap and Bells” was, in retrospect, a counter-poem to the beautiful but abject “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven,” which he described as “the way to lose a woman.” Being “poor” (the nonce word in this poem “Enwrought with golden and silver light”), he cannot afford “the heaven’s embroidered cloths,” and so “I have spread my dreams under your feet;/ Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

This is to invite the female response Nancy Sinatra threatened a half-century ago: “These boots are made for walking, and that’s just what they’ll do. / One of these days these boots are gonna walk all over you” as well as the recent pictorial spoof by Annie West.

Annie West cartoon from her series “Yeats in Love”

Annie West cartoon from her series “Yeats in Love”

If he was not engaging in either massive repression or sardonic irony in describing the even more beautiful and even more masochistic “The Cap and Bells” as “the way to win a woman,” Yeats must have believed that Maud Gonne was to be won only through total sacrifice.

In a chivalric scenario set in the evening in a garden beneath the palace-window of a young, beautiful, and aloof queen, a lovelorn jester bids his blue-garmented soul, “grown wise-tongued by thinking” of her “light foot fall,” to rise upward to her window-sill. Unresponsive, she decisively “drew in the heavy casement/ And pushed the latches down.” He then sends her, in a “red and quivering garment,” his heart, “grown sweet-tongued by dreaming/ Of a flutter of flower-like hair.” It “sang to her through the door.” But the dismissal of the heart is even more painful because so nonchalant: “she took up her fan from the table/ And waved it off on the air.” With soul and heart, thought and dream, both rejected, he sends the young queen what is most quintessential, at once the symbol of his occupation and (it takes no Freud to tell us) of his manhood: “I have cap and bells,” he ponders; “I will send them to her and die.” And, “when the morning whitened/ He left them where she went by.”

She laid them upon her bosom,

Under a cloud of her hair,

And her red lips sang them a love-song

Till stars grew out of the air.

In the original draft, “She took them into her chamber/ Her breast began to heave,” less in grief than triumph. Though Yeats deleted these lines disturbing the poem’s ethereal tone, their morbid eroticism (which would flower perversely in his late dance plays where lowly fools are decapitated to appease haughty queens) offers a psychological glimpse into the poem’s human, all-too-human origins. When, at last, the queen lets in soul and heart, they set up a “chattering wise and sweet,/And her hair was a folded flower/ And the quiet of love in her feet.” But it seems too little too late. Soul and heart had “grown” through suffering. Now her “red lips” sang his final offering “a love-song/ Till stars grew out of the air.” Grew, because, in a variation on the mythic origin of the constellation Coma Berenices,[14] her star-making song’s genesis lies in his lethal self-sacrifice. Here as “always” in Yeats, a “personal emotion” has been “woven into a general pattern of myth and symbol” (Autobiographies [1955] 151). But on the “personal” level of this medieval Poet/Muse drama, the belle dame sans merci to whom the lowly jester gives “all” is unmistakably Maud, “that one” who (in “Friends”) “took/ All till my youth was gone/ With scarce a pitying look.” “The Cap and Bells” ends with “the quiet of love in her feet”; but they are the very “feet” under which he had “spread my dreams” in the abject poem supposedly rebutted in a ballad of terrible beauty, lyrically lovely but psychologically rooted in a symbolic act of self-castration.

These are covert Maud poems. The most overt, the only poem in which Yeats claims, in his own name, that his passion for Maud was reciprocated, is “To a Young Girl” (1915) in The Wild Swans at Coole.[15] The girl addressed is Maud’s daughter Iseult (not adopted, as she publicly claimed, but the fruit of her liaison with the French activist, Lucien Millevoye). Like many of Yeats’s middle poems, this one is short and “thin”: a single sentence, one syntactical unit spun out over eleven three-beat lines. In another irony, Iseult had come to Yeats, of all people, for advice in love. His response contains perhaps more than Iseult needed to know:

My dear, my dear, I know

More than another

What makes your heart beat so;

Not even your own mother

Can know it as I know,

Who broke my heart for her

When the wild thought,

That she denies

And has forgot,

Set all her blood astir

And glittered in her eyes.

He acknowledges his own intensity in “Friends,” written four years earlier. “Now must I these three praise—/ Three women that have wrought/ What joy is in my days….” Naming no names, he begins with Olivia Shakespear, praised because, over fifteen “troubled years,” no thought “Could ever come between/ Mind and delighted mind.” Next is Yeats’s friend and patron, Lady Augusta Gregory, whose steady “hand” had the strength to unbind “Youth’s dreamy load, till she/ So changed me that I live/ Labouring in ecstasy.” But the third and climactic figure to be praised presents a challenge. Yeats poses two questions, and answers them:

And what of her that took

All till my youth was gone

With scarce a pitying look?

How could I praise that one?

When day begins to break

I count my good and bad,

Being wakeful for her sake,

Remembering what she had,

What eagle look still shows,

While up from my heart’s root

So great a sweetness flows

I shake from head to foot.

That image will be repeated in the “Dialogue,” where “So great a sweetness flows into the breast” that it absorbs and absolves the “folly” the Self “does or must suffer” if he loves a “proud woman not kindred of his soul”: that most painful yet “most fecund” ditch of all. If there were no Maud Gonne, Yeats would have invented her, requiring, like most poets in the Romantic and Celtic traditions, a Muse, an enchantress, a femme fatale who is a life-giving yet destructive goddess. But there was a Maud Gonne, a pre-Raphaelite “stunner” who combined all three roles, along with being a committed and passionate Irish patriot. The impact on Yeats as a man and as a poet is attested to by innumerable shorter lyrics, and she figures in major poems as well—in “The Tower,” II, as the “woman lost,” and in the “plunge…/ Into the labyrinth of another’s being.” And she is at the heart of one of Yeats’s indisputable masterpieces, “Among School Children.”

Maud serves as warning and counter-example in the paternalistic, conservative, but nevertheless beautiful “A Prayer for my Daughter.” The protective father prays that Anne, “half-hid/ Under this cradle-hood and coverlid,” yet born into the violent world and “rocking cradle” evoked in the immediately preceding poem, “The Second Coming,” will be granted moderate rather than excessive, troubling beauty and “natural kindness” free of rancorous political hatred. For “Have I not seen the loveliest woman born/ Out of the mouth of Plenty’s horn,” because of her politics and “opinionated” mind, “Barter that horn and every good/ By quiet natures understood/ For an old bellows full of angry wind?” I’ll later propose a relationship between “Among School Children” and the final Maud Gonne poem, “A Bronze Head.” But for now let’s browse through some earlier Maud lyrics.

§

Beautiful as many of them are, most of the poems to his “Beloved” in The Rose (1893) and even in The Wind Among the Reeds (1899), are too “heavy” with dream and dew, too perfumed with fin-de-siècle “lilies of death-pale hope, roses of passionate dream” (“The Travail of Passion,” 1896), too filled with languor and dim hair, to move most modern readers. My favorite poem in The Rose—the song James Joyce sang in lieu of the requested prayer at his mother’s deathbed and that haunts Stephen Dedalus throughout Bloomsday—is “Who Goes with Fergus?” The king of Ulster who put aside his crown to live in peace and “pierce the deep wood’s woven shade” invites a young man and maid to join him in his forest paradise, where they will “brood on hopes and fear no more”;

And no more turn aside and brood

Upon love’s bitter mystery;

For Fergus rules the brazen cars,

And rules the shadows of the wood,

And the white breast of the dim sea

And all disheveled wandering stars.

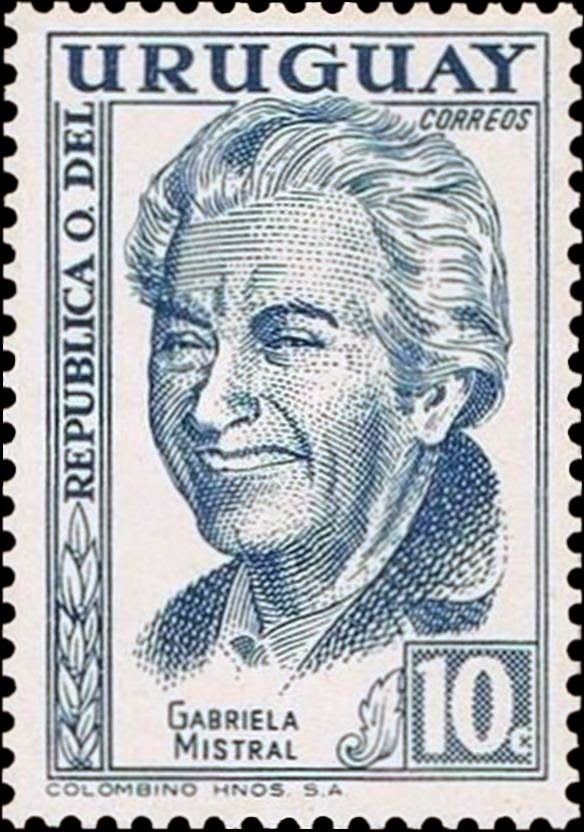

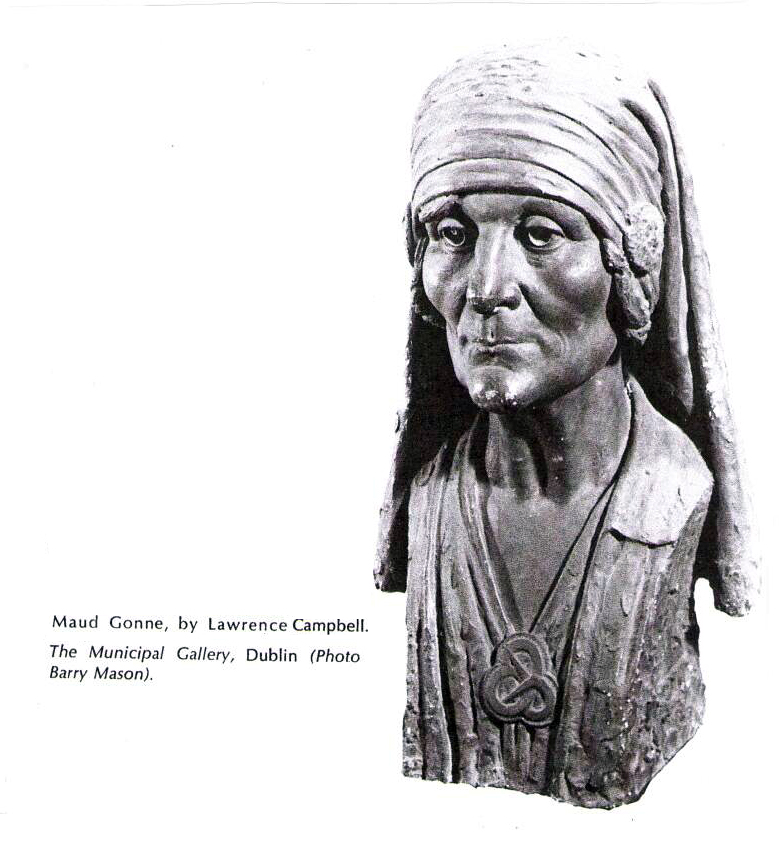

Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne

But despite the emotional respite promised, the poem’s imagery—“shadows” of the wood, the “white breast” of the sea, the “disheveled” stars –extends to this supposedly peaceful paradise all the erotic tumult of “love’s bitter mystery.” That phrase alone might summon up Maud, but the beautiful final line suggests a deeper connection. “All disheveled wandering stars” fuses Eve’s “disheveled hair” (Paradise Lost 4:306) with Pope’s echo in The Rape of the Lock, which ends with Belinda’s shorn tresses consecrated “midst the Stars”: “Not Berenices’s Locks first rose so bright,/ The Heavens bespangling with disheveled Light.” A year after writing the Fergus poem, Yeats would have his young queen, a medieval version of Maud, place her lovelorn jester’s cap and bells under “a cloud of her hair,” and “her red lips” would sing “them a love song/ Till stars grew out of the air.”

Stars reappear in the most familiar poem in The Rose, “When You Are Old,” which departs from its original in Ronsard. As Maud grew older, Yeats obsessively summoned up her youthful beauty; here, he imagines her, at the age of twenty-five, “old and grey and full of sleep,/ And nodding by the fire.” Then, he tells her, take down “this book,” written by the “one man” who “loved the pilgrim soul in you”;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

But the first Maud poem in Yeats’s more naked style is “The Arrow” (1901), which opens the Maud-cluster in In the Seven Woods (1904), poems addressed to a Muse now in her ‘thirties. The enjambed lines of “The Arrow,” in tension with its taut couplets, are all in “feminine” or double rhyme, a stressed followed by an unstressed syllable, a falling pattern established with the title-word itself :

I thought of your beauty, and this arrow,

Made out of a wild thought, is in my marrow.

There’s no man may look upon her, no man,

As when newly grown to be a woman,

Tall and noble but with face and bosom

Delicate in colour as apple blossom.

This beauty’s kinder, yet for a reason

I could weep that the old is out of season.

In the next poem, a “kind” friend (in fact, Lady Gregory), counseling “patience,” suggests that “time” and the diminution of Maud’s extravagant youthful beauty should “make it easier to be wise.” But

…………………………….Heart cries, “No,

I have not a crumb of comfort, not a grain.

Time can but make her beauty over again:

Because of that great nobleness of hers

The fire that stirs about her when she stirs,

Burns but more clearly. O she had not these ways

When all the wild summer was in her gaze.”

O heart! O heart! If she’d but turn her head,

You’d know the folly of being comforted.

He has, he tells Maud and us in “Old Memory,” thought and written about her “Through the long years of youth, and who would have thought” that it would all have “come to naught,/ And that dear words meant nothing? But enough,/ For when we have blamed the wind we can blame love.” In “Never Give all the Heart,” he advises us to “never give the heart outright” to passionate women. For they

Have given their hearts up to the play,

And who could play it well enough

If deaf and dumb and blind with love?

He that made this knows all the cost,

For he gave all his heart and lost.

In the next poem, the plangent “Adam’s Curse” (1902), Maud sits silently by while her sister Kathleen and the poet discuss on a late summer evening various forms of “labour.” They include the poet’s quest, even if a line “takes hours” to write, to “make it seem a moment’s thought,” and Kathleen’s intuitive knowledge that a woman “must labour to be beautiful.” It’s certain, he responds, that “there is no fine thing/ Since Adam’s fall but needs much labouring.” There have been

……………..“lovers who thought love should be

So much compounded of high courtesy

That they would sigh and quote with learned looks

Precedents out of beautiful old books;

Yet now it seems an idle trade enough.”

We sat grown quiet at the name of love;

We saw the last embers of daylight die,

And in the trembling blue-green of the sky

A moon, worn as if it had been a shell

Washed by time’s waters as they rose and fell

About the stars and broke in days and years.

I had a thought for no one’s but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.

So much for the courtly love tradition. This same year, Yeats had put Maud on stage as Ireland herself in Cathleen ni Houlihan. That “Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland” was her favorite Yeats poem is unsurprising. Written in 1894 but now incorporated in this sequence, it makes Maud indistinguishable from Cathleen as Ireland. Most readers are thrilled by the couplet on one queen’s mountain cairn: “The wind has bundled up the clouds high over Knocknarea,/ And thrown the thunder on the stones for all that Maeve can say.” But it was surely this stanza’s final lines—echoing “the quiet of love in her feet” from the finale of “The Cap and Bells,” written a year earlier—that appealed to Maud, servant of another queen: Angers like “noisy clouds” may have “set our hearts abeat;/ But we have all bent low and low and kissed the quiet feet/ Of Cathleen, the daughter of Houlihan.”

The Green Helmet and Other Poems (1910) opens with a cluster celebrating Maud as a Helen of Troy redivivus. He has dwelt on and written about her for so long that he dreams he has “brought/ To such a pitch my thought/ That coming time can say/ ‘He shadowed in a glass/ What thing her body was.’”

For she had fiery blood

When I was young,

And trod so sweetly proud

As ‘twere upon a cloud,

A woman Homer sung,

That life and letters seem

But an heroic dream.

Now that he has “come into my strength,/ And words obey my call,” he hopes, in the next poem, “Words,” that, “At length,/ My darling understands it all.” Yet “Had she done so who can say/ What might have shaken from the sieve?/ I might have thrown poor words away/ And been content to live.” But Yeats does not really believe that the poetry was a mere substitute for life and sex. Even if it is in part sublimation, the poetry itself matters. It is in a poem, after all, that he speculates that, had his love been requited, he “might” have “thrown poor words away.” It wasn’t; he didn’t. The poet in him “turned aside” from Maud to “words.”

“Words” is followed by the more famous “No Second Troy,” consisting of two five-line rhetorical questions, followed by two more, each distilled to a single line. We are initially seduced into sharing the poet’s complaint; he had abundant reason to “blame” her, she having “filled” his days, not with joy, but “with misery.” But Yeats is setting us up; his rhetorical strategy reveals our own pettiness faced with a Helen born out of phase, a classic figure living in a modern age unworthy of her.

Why should I blame her that she filled my days

With misery, or that she would of late

Have taught to ignorant men most violent ways,

Or hurled the little streets upon the great,

Had they but courage equal to desire?

What could have made her peaceful with a mind

That nobleness made simple as a fire,

With beauty like a tightened bow, a kind

That is not natural in an age like this,

Being high and solitary and most stern?

Why, what could she have done, being what she is?

Was there another Troy for her to burn?

With no Troy to burn, her incendiary energy had to be directed to what was at hand: whether Ireland or Yeats himself, both, perhaps, lacking “courage equal to desire.” But she could do no other. In acting as she did, she was being true to her quintessential being: “what she is.” What is to “blame,” outrageously enough, is not the terrible beauty of Yeats’s magnificent heroine, “high and solitary and most stern,” but the low, gregarious, and ignoble modern world itself, for not being (as Richard Ellmann once wittily remarked) “heroically inflammable.” The question of “blame” is also raised in the opening line of the next poem in the sequence.

During a public lecture in 1903, Yeats was suddenly informed of Maud’s marriage. The unexpected news struck him like a thunderbolt. “Reconciliation,” the poem immediately following “No Second Troy,” records that reaction. The background includes her subsequent separation from John MacBride (later an Easter Rising martyr, but at the time a drinker abusive to Maud and, perhaps, Iseult), and the reunion of Maud and Yeats, at long last, if briefly, sexual (in Paris in December 1908).[16] Like “No Second Troy,” “Reconciliation” is twelve lines of iambic pentameter, though this time in couplets:

Some may have blamed you that you took away

The verses that could move them on the day

When, the ears being deafened, the sight of the eyes blind

With lightning, you went from me, and I could find

Nothing to make a song about but kings,

Helmets, and swords, and half-forgotten things

That were like memories of you—but now

We’ll out, for the world lives as long ago;

And while we’re in our laughing, weeping fit,

Hurl helmets, crowns, and swords into the pit.

But, dear, cling close to me; since you were gone,

My barren thoughts have chilled me to the bone.

The sequence ends with “Peace,” depicting her fascinating and oxymoronic mingling of “charm” and “sternness,” Scripture’s lion and the honey-comb (“All that sweetness amid strength”), and concluding, “Ah, but peace that comes at length,/ Came when Time had touched her form.”

Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne

Responsibilities (1914), much more focused on public issues, contains only a handful of Maud-related poems toward the end; but the volume is prefaced by intimately personal untitled lines directed to his ancestors, asking their “Pardon that for a barren passion’s sake,” he has no child, “nothing but a book,/ Nothing but that to prove your blood and mine.” The little cluster of Maud poems begins with “A Memory of Youth.” Reminiscent of “Adam’s Curse,” it records moments of play and wit, until “A cloud blown from the cut-throat north/ Suddenly hid love’s moon away.” Praise of his beloved’s body and mind had brightened her eyes and brought a blush to her cheek, “Yet we, for all that praise, could find/ Nothing but darkness overhead.” They sit in stony silence, knowing, “though she’d said not a word,/ That even the best of love must die.” They had been “savagely undone,” but for a sudden burst of emotion-revivifying illumination, when “Love upon the cry/ Of a most ridiculous little bird/ Tore from the clouds his marvelous moon.”

Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne

The next poem, “Fallen Majesty,” records “what’s gone.” Although “crowds gathered once if she but showed her face,” now one might gather, and “not know it walks the very street/ Whereon a thing once walked that seemed a burning cloud.” Following “Friends,” cited earlier, come two somewhat mysterious, almost apocalyptic poems, “The Cold Heaven” and “That the Night Come.” The latter presents a woman who so “lived in stir and strife,” that her soul, desiring what “proud death may bring,” could “not endure/ The common good of life,” seeming “To bundle time away/ That the night come.” The thrilling but enigmatic “The Cold Heaven” requires A Vision to be fully explicated, but no mumbo-jumbo about the posthumous “Dreaming Back” stage of the “Spirit” is needed to explain why

…………….imagination and heart were driven

So wild that every casual thought of that and this

Vanished, and left but memories, that should be out of season

With the hot blood of youth, of love crossed long ago;

And I took all the blame out of all sense and reason,

Until I cried and trembled and rocked to and fro,

Riddled with light.

The next volume, the autumnal The Wild Swans at Coole (1919), is haunted by the memories of a man in his fifties, but feeling older. He is thinking of Iseult in “The Living Beauty” (“O heart, we are old;/ The living beauty is for younger men:/ We cannot pay its tribute of wild tears”); but the heartache in the volume’s title poem mingles echoes of Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” and Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” with memories of Maud and of his own lost youth. In autumn, at twilight, he has looked on the swans, paired lovers, “And now my heart is sore.”

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

The swans seem changeless, but “All’s changed” with him, not only because the “nineteenth autumn has come upon” him since he first counted those wild and “brilliant creatures,” but because he is writing in the immediate aftermath of Maud’s recent rejection of yet another proposal of marriage. Perhaps that is why there are “nine-and-fifty swans,” one unpaired and solitary.[17]

Five poems in The Wild Swans at Coole focus on Maud herself (“Her Praise,” “The People,” “His Phoenix,” “A Thought from Propertius,” and “Broken Dreams”); and the poem preceding them, “On Woman,” is a Maud poem in biblical disguise. Since “Her Praise” and “The People” pay tribute to her work on behalf of the Irish people, they are not quite Muse poems.[18] The lighthearted “His Phoenix” ticks off, in jaunty hexameters, a “crowd” of women “through all the centuries,” starting with Leda and including the famed dancers Ruth St. Denis and Pavlova. “And who can say but some young belle may walk and talk men wild/ Who is my beauty’s equal,” though that his “heart denies.” For none could reproduce her “exact likeness”: the “simplicity of a child,/ And that proud look as though she had gazed into the burning sun,” as well as that “shapely body” with not the slightest detail “gone astray./ I mourn for that most lonely thing; and yet God’s will be done:/ I knew a phoenix in my youth, so let them have their day.”

In “A Thought from Propertius,” echoing the second Elegy of Sextus Propertius, Yeats imagines Maud “fit spoil for a centaur/ Drunk with the unmixed wine,” yet “so noble from head” to foot that she might have “walked to the altar/ Through the holy images/ At Pallas Athena’s side.” (In 1938, enumerating “Beautiful Lofty Things,” images of “Olympian” nobility impressed on his memory, Yeats concludes with “Maud Gonne at Howth station waiting a train,/ Pallas Athena in that straight back and arrogant head”—the single reference to her by name in his poetry.) The Propertius poem, eight tight lines, is followed by “Broken Dreams,” 41 lines of artfully rambling reverie, rhymed but written in a semblance of free verse to match its almost free associations. Maud was now in her early fifties, a fact registered in the poem’s opening lines: “There is grey in your hair./ Young men no longer suddenly catch their breath when you are passing.” Yet

For your sole sake—that all heart’s ache have known,

And given to others all heart’s ache,

From meager girlhood’s putting on

Burdensome beauty—for your sole sake

Heaven has put away the stroke of her doom,

So great her portion in that peace you make

By merely walking in a room.

He imagines some young man asking an old man, “Tell me of that lady/ The poet stubborn with his passion sang us/ When age might well have chilled his blood.” In a desperate certainty reflecting his reading of Plotinus and Swedenborg, he is confident that “in the grave all, all shall be renewed,” and that “I shall see that lady/ Leaning or standing or walking/ In the first loveliness of womanhood,/ And with the fervor of my youthful eyes.” And yet, though she is “more beautiful than anyone,” she had a flaw; her small hands were not beautiful, and he is afraid that she will run, and “paddle to the wrist” in “that mysterious, always brimming lake/ Where” the blessed “Paddle and are perfect. Leave unchanged/ The hands that I have kissed,/ For old sake’s sake.” The “last stroke of midnight dies,” ending a day in which he has “ranged” from “dream to dream and rhyme to rhyme,” in “rambling talk with an image of air:/ Vague memories, nothing but memories.”

This Maud-cluster is preceded by “On Woman” and framed by two short lyrics to be discussed in a moment. Written in May 1914, “On Woman” anticipates the 1918 “Solomon to Sheba” and “Solomon and the Witch.” But unlike those poems, composed after his marriage and addressed to his wife, this Solomon and Sheba poem has to do with Maud. We are told that Solomon “never could,” although “he counted grass,/ Count all the praises due/ When Sheba was his lass.” The sexual “shudder that made them one” anticipates “Leda and the Swan,” but the lines that immediately follow (and conclude the poem) anticipate Self’s choice, in the “Dialogue,” of eternal recurrence, with its “fecund” intermingling of joy and pain. The thought might make you “throw yourself down and gnash your teeth,” says Nietzsche’s demon in the passage introducing the thought-experiment or ordeal of Eternal Recurrence. But have you, even “once,” experienced a “moment” so “tremendous” that you “fervently craved” it “once more” and “eternally”? (The Gay Science §341). The speaker in “On Woman” prays that God grant him, not “here,” for he is “not so bold” as to “hope a thing so dear/ Now I am growing old,”

But when, if the tale’s true,

The Pestle of the moon

That pounds up all anew

Brings me to birth again—

To find what once I had

And know what once I have known,

Until I am driven mad,

Sleep driven from my bed,

By tenderness and care,

Pity, an aching head,

Gnashing of teeth, despair;

And all because of some one

Perverse creature of chance,

And live like Solomon

That Sheba led a dance.

‘The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon’, oil on canvas by Edward Poynter, 1890.

‘The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon’, oil on canvas by Edward Poynter, 1890.

Here, as in “Broken Dreams” and, a decade and a half later, in “Quarrel in Old Age,” Yeats invokes renewal beyond the grave. “All lives that has lived,” he announces in “Quarrel” (1931); “Old sages were not deceived:/ Somewhere beyond the curtain/ Of deceiving days/ Lives that lonely thing/ That shone before these eyes”: Maud, who seemed armed like a goddess and “Trod like Spring.” It is a recurrent hope, compounded of Plotinus, Swedenborg’s vision of frustrated lovers posthumously united, and the embrace, by Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, of the eternal recurrence of passion and joy, no matter the attendant and inevitable suffering. And “all because of one/ Perverse creature”—“that one.”

The two short framing lyrics I referred to both consist of six trimeter lines rhymed abcabc, and both emphasize the indelible imprint of the One among the many. Again, she is unique; there are all the “others,” and then there is Maud. The title of the first, “Memory,” could refer to all the Maud Gonne poems:

One had a lovely face,

And two or three had charm.

But charm and face were in vain

Because the mountain grass

Cannot but keep the form

Where the mountain hare has lain.

What better image for the impress of memory than the crushed grass where the elusive mountain-rabbit has lain? She is gone, but the “form” remains forever.

Maud told Yeats she would never marry him, and that he should be “glad,” since “you make such beautiful poetry out of what you call your unhappiness.” But she also swore she would marry no one else. She did. “A Deep-sworn Vow” registers that broken oath and its sexual consequences for him. Yet he has been faithful in his fashion; for “always,” at intense moments of truth, when the defense mechanisms are down, there is a sudden return of the repressed:

Others because you did not keep

That deep-sworn vow have been friends of mine;

Yet always when I look death in the face,

When I clamber to the heights of sleep,

Or when I grow excited with wine,

Suddenly I meet your face.

However expected, the revelation is sudden. As in the discovery of true love in Poem IV of “A Woman Young and Old”—“And now we stare astonished at the sea”—Yeats is here recalling the sestet of the sonnet in which Keats compared his discovery of Homer to the awed moment when the ocean’s Spanish discoverers “stared at the Pacific,” and the conquistador and his men looked at each other “with a wild surmise—/ Silent, upon a peak in Darien.” In “A Deep-sworn Vow,” Yeats does not fall asleep; instead, he vigorously “clambers” to its visionary “heights.” He also repeats (heights, excited, wine) the long i of Keats’s wild, surmise, silent. And both poems end with a double-caesura preceding the abrupt revelation: in the case of “A Deep-sworn Vow,” Maud’s “face” looming up from the subconscious. It is a chthonic apparition; the highly unusual exact rhyme makes her “face” indistinguishable from the “face” of death, as befits a femme fatale.

§

Since the death’s-head image culminates in the last and most somberly impressive of the Maud Gonne poems, “A Bronze Head” (1938), I will move directly to that poem, deferring comment on two Maud-related poems (“An Image from a Past Life” and “Under Saturn”) from Michael Robartes and the Dancer (1921), the volume that follows The Wild Swans at Coole. I have already noted the presence of Maud in the 1921 volume’s “A Prayer for my Daughter.”

As mentioned earlier, “A Bronze Head” is related to “Among School Children.” Just as Purgatory is the dark twin of “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” animating the terror implicit in Nietzschean Eternal Recurrence (the enactment “again, and yet again,” ultimately embraced in the “Dialogue”), so “A Bronze Head” seems a darker reexamination of the relationships explored in “Among School Children” between unity and division, the One and the Many, underlying substance and its various manifestations. The crucial philosophic question and speculation in the later poem is restricted to Maud, ever a shape-shifter: “who can tell/ Which of her forms has shown her substance right?/ Or maybe substance can be composite….” This would be no less at home in the poem in which the Yeatsian old man walks through the long schoolroom “questioning,” dreaming of a “Ledaean body,” Maud’s, and what came before and after: the beloved as “child” and in her “present” form, feeding on the insubstantial, her image (visually Dantesque, verbally Shakespearean) “Hollow of cheek as though it drank the wind/ And took a mess of shadows for its meat.”[19]

That is the image, though even further time-ravaged, sculpted in the plaster of Lawrence Campbell’s bronze-painted bust in the Municipal Gallery. But not even the titular sculpture could permanently fix the protean image of his beloved for Yeats. She is an artifact, but also something “Human, superhuman, a bird’s round eye,/ Everything else withered and mummy-dead.” Though now a “great tomb-haunter” sweeping the “distant sky” and terrified by the “Hysterica passio” of her “own emptiness,” she was “once” a “form all full/ As though with magnanimity of light.” Yet she is also “a most gentle woman.” And there is more. As the poet first saw her, she was an unmanageable filly—“even at the starting post, all sleek and new,/ I saw the wildness in her”—and a vulnerable human creature, her animal wildness transferred by empathy to the protective poet-lover, who “had grown wild/ And wandered murmuring everywhere, ‘My child, my child!’” Finally, returning to the “bird’s round eye” of the opening stanza, Yeats describes her in her anything but vulnerable aspect: “Or else I thought her supernatural;/ As though a sterner eye looked through her eye/ On this foul world in its decline and fall….”

Dispensing round his magnanimity of images, Yeats goes beyond the triads of “Among School Children”—though there too Maud had been evoked as child, beautiful woman, and aged crone, even as bird (a Ledaean “daughter of the swan”) and animal (a wind-drinking chameleon). “Among School Children” questions the chestnut-tree of the final stanza: “Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?” It is of course all three since we can no more break down the organic unity of that “great-rooted blossomer” than we can “know the dancer from the dance,” or isolate Maud as child from Maud as “Ledaean body,” or from her “present image” as hollow-cheeked but still voracious crone. Yet it is as a crone that Yeats compels us to envisage Maud Gonne in “A Bronze Head”—compels us by ending his poem in a repetition and intensification of that “present image.” The birdlike “sterner eye” looking through Maud’s eye—that “mysterious eye” that, Yeats reports with fascination and dread (Memoirs, 60), British journalists felt “contained the shadow of battles yet to come”—seems not only Yeats’s own eye, as I suggested at the outset, but that of the Morrigu, the one-eyed “woman with the head of a crow.” It seems to be that Celtic war-goddess who presides here, as in The Death of Cuchulain, her “sterner eye looking through [Maud’s] eye/ On this foul world in its decline and fall,” and wondering “what was left for massacre to save.”

The Morrigu, the Celtic demoniac bird of the dead who haunts corpse-strewn battlefields, is the dark side of the Old Woman, Cathleen ni Houilihan, who demands “all” of her devotees in the passages Yeats wrote for Maud in the 1902 play in which she personified the oppression and resurrection of Ireland: the old crone transfigured into “a young girl” with “the walk of a queen,” rejuvenated by blood-sacrifice. That climax was anticipated, reports Stephen Gwynn, present on opening-night, when Maud’s Cathleen rose, “still bent and weighed down with years or centuries; but for one instant, before she went out at the half-door, she drew herself up to her superb height; change was manifest; patuit dea.” Gwynn’s Virgilian allusion is apt; though she is disguised as a Spartan huntress, Venus was revealed to Aeneus as she walked away, vera incessu patuit dea, “the true goddess revealed in her step” (Aeneid 1.405). But Gwynn also “went home asking myself if such plays should be produced unless one was prepared for people to go out to shoot and be shot.”[20] As we will see, Yeats asked himself that very question preparing for his own death. Maud, too, comes full circle: from the beautiful woman, bent and hidden under the rags of the Old Woman of Cathleen ni Houlihan, to an actual old woman: the literal terrible beauty of “A Bronze Head.”

No wonder there were “others,” none as magnetic as Maud, yet minor Muses. Olivia introduced him to sexual love, but could not uproot Maud. “I had a beautiful friend,” he mourns in an 1898 poem, “And dreamed that the old despair/ Would end in love in the end:/ She looked in my heart one day,/ And saw your image was there.”[21] Despite the tearful parting that followed, lovely Olivia remained his lifelong friend and most intimate correspondent. In one late letter (December 18, 1929), Yeats sent her the moving “After Long Silence,” its heartache distilled in the single word “young” hovering at the end of the penultimate line:

Speech after long silence; it is right,

All other lovers being estranged or dead,

Unfriendly lamplight hid under its shade,

The curtains drawn upon unfriendly night,

That we descant and yet again descant

Upon the supreme theme of Art and Song:

Bodily decrepitude is wisdom; young

We loved each other and were ignorant.

Olivia Shakespear

Olivia Shakespear

The late marriage to his wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees, in 1917 (he was 52, she half his age) ushered in Yeats’s most creative period. Her interest in the visionary and occult matched his, her gift of automatic writing generating his book A Vision (1925, 1937). In “Under Saturn” (November 1919), he asks “how should I forget the wisdom that you brought,/ The comfort that you made?” But he has to ask the question in the first place because, having “grown saturnine,” he fears she might “Imagine that lost love, inseparable from my thought/ Because I have no other youth, can make me pine.” Like Olivia, George (as Yeats preferred to call her) saw Maud’s image there. In “An Image from a Past Life,” the immediately preceding dialogue-poem, She, possessed like George of occult powers, senses that

A sweetheart from another life floats there

As though she had been forced to linger

From vague distress

Or arrogant loveliness,

Merely to loosen out a tress

Among the starry eddies of her hair

Upon the paleness of a finger.

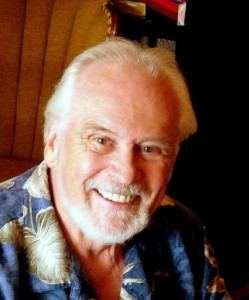

William Butler Yeats and his wife Georgie in the late 1920s.

William Butler Yeats and his wife Georgie in the late 1920s.

He reassures her that any such image, “even to eyes that beauty had driven mad,” can only “make me fonder.” Unconvinced, She does not know whether the uplifted arms of the spectral figure intend to “flout me,” or “but to find,/ Now that no fingers bind,/ That her hair streams upon the wind.” What she does know is that “I am afraid/ Of the hovering thing night brought me.”

Given the context of the ghostly and mysterious wisdom brought to the poet through Mrs. Yeats’s occult “Communicators,” it is unsurprising that his greatest “love poem” to his wife should occur in the Browningesque dramatic monologue, “The Gift of Harun Al-Rashid” (1924). The “gift” the great Caliph gives to his friend and learned treasurer Kusta Ben Luka is a woman who “shares” his “thirst” for “old crabbed mysteries, “yet “herself can seem youth’s very fountain,/ Being all brimmed with life” (85-90), Whatever the “Voice” of the Djinn she heard, Kusta comes to realize that his young wife is not simply a conduit; that that mysterious voice has drawn

A quality of wisdom from her love’s

Particular quality. The signs and shapes,

All those abstractions that you fancied were

From the great Treatise of Parmenides;

All, all those gyres and cubes and midnight things

Are but a new expression of her body

Drunk with the bitter sweetness of her youth.

And now my utmost mystery is out. (179-87)

But this revelation is followed immediately by the poem’s concluding lines, in which Kusta-Yeats insists that, while “A woman’s beauty is a storm-tossed banner,” he is neither “dazzled by the embroidery, nor lost / In the confusion of its night-dark folds.” Within the poem, this imagery echoes the opening lines about the “banners of the Caliphs” hanging “night-coloured/ But brilliant as the night’s embroidery” (6-7). However, in the context of the full canon of Yeats’s love-poetry, the image inevitably recalls “the heaven’s embroidered cloths”— “Enwrought with golden and silver light,/ The blue and the dim and the dark cloths/ Of night and light and the half-light”—the young, Maud-infatuated poet wished to “spread…under your feet.”

Now, a quarter-century later, he is no longer “dazzled” by the storm-tossed and night-dark but brilliant embroidery because, ostensibly, he is choosing wisdom over beauty—autobiographically, George over Maud. This is what he had actually done in January 1919, when he turned Maud from the door of her own house, 73 St. Stephen’s Green, which she’d rented to the poet and his wife. Returned from London to relish the Sinn Fein victory in the December 1918 elections, Maud was in Ireland illegally. George was not only pregnant with Anne, but gravely ill of the influenza that killed millions in the aftermath of World War I. Fearing the police might burst in during such a crisis, Yeats, soon accused of cowardice by Maud and her supporters for his threshold rejection, “turned aside” from her, choosing the Vesta of hearth and family over his storm-tossed night-visitor and Muse.[22]

Still, as we’ve seen, and as suggested by the intrusion of the embroidery-image on the heels of Kusta-Yeats’s tribute to his bride, Yeats’s genuine feelings for his wife did not preclude ghostly visitations by past images of Maud—and present images of Iseult, to whom Yeats, in September 1917, having been rejected yet again by Maud and before approaching George, had proposed marriage. Like mother, like daughter. As Yeats’s “Heart” tells him in a poem written the following month: “How could she mate with fifty years that was so wildly bred?/ Let the cage bird and the cage bird mate and the wild bird mate in the wild.” This poem, “Owen Aherne and his Dancers,” was saved for The Tower, where it leads directly into the sequence “A Man Young and Old,” autobiography masked as Everyman. The emotional/ erotic tensions involving Yeats and his new wife, Maud and Iseult, also play out symbolically in The Only Jealousy of Emer (1919), the most lyrical of the Cuchulain plays. That play opens with the First Musician’s “Song for the folding and unfolding of the cloth,” in which the “loveliness” of “a woman’s beauty” is compared to that of a “white sea-bird alone/ At daybreak after a stormy night,” and to an “exquisite” sea-shell the “vast troubled waters bring/ To the loud sands before day has broken” : a beauty-producing violence “imagined within/ The labyrinth of the mind,” an autobiographical maze intricate enough to enfold three women barely detectable beneath the otherworldly mythology.

Iseult Gonne

Iseult Gonne

There were more palpably intimate post-marital relationships,[23] including a late liaison, following others with Margot Ruddock and Ethel Mannin, with Edith Shackleton Heald, who, as we’ve seen, visited Yeats’s grave in Roquebrune cemetery. His relationship with Lady Dorothy Wellesley was poetic (they collaborated on “The Three Bushes” and its attendant lyrics, and talked much of poetry) and, though passionate, was non-sexual; she was lesbian. But she did inspire the eerie and rather overwrought “To Dorothy Wellesley” (1936), in which he imagines her stretching her hand “towards the moonless midnight of the trees,” and, “Rammed full/ Of that most sensuous silence of the night,” climbing to “your chamber full of books.” The poem strains toward, and attains, a final sublimity:

……………………..What climbs the stair?

Nothing that common women ponder on

If you are worth my hope! Neither Content

Nor satisfied Conscience, but that great family

Some ancient famous authors misrepresent,

The Proud Furies each with her torch on high.

But, to state the obvious, there can be no doubt that it was, above all, Maud— “that one”—who simultaneously broke Yeats’s heart, fascinated him, and inspired the greatest love poetry of the twentieth century. Harold Bloom, an anything but uncritical admirer, has rightly said of Yeats as a love poet: “one can wonder if any poet of our century enters into competition here with him.”[24] She also transfigured him in the process. I’m alluding to “First Love,” the opening poem of “A Man Young and Old,” which concludes The Tower just as “A Woman Young and Old” concludes The Winding Stair.

Here, Yeats’s mask as Everyman slips from the outset, and the lunar figure is clearly based on Maud. “Though nurtured like the sailing moon/ In beauty’s murderous brood,” she “walked” and “blushed” awhile and “on my pathway stood/ Until I thought her body bore/ A heart of flesh and blood.” But since he “laid a hand thereon,/ And found a heart of stone,” he realizes that “every hand is lunatic./ That travels on the moon.” She “smiled and that transfigured me/ And left me but a lout,” wandering aimlessly, “Emptier of thought/ Than the heavenly circuit of its stars/ When the moon sails out.” And this final stanza of the first poem leads directly to the lunar opening of the next in the sequence: “Like the moon her kindness is/ If kindness I may call” what has no “comprehension” in it, “But is the same for all/ As though my sorrow were a scene/ Upon a painted wall.”

It should be mentioned that, in contrast to most of this man-centered sequence, poem IV, “The Death of the Hare,” expresses unexpected empathy for the female in the love-hunt. The Man’s “heart is wrung,” when he remembers her “wildness lost.” He experiences the “yelling pack,” and, finally, the death of the pursued animal. “The Death of the Hare,” looking back to “Memory,” anticipates the “stricken rabbit” whose death-cry “distracts” Yeats’s “thought” in “Man and the Echo.” It also anticipates the empathy with the female perspective expressed throughout “A Woman Young and Old.”

The poems that follow in the “Man” sequence emphasize the tragedy at the heart of the Yeats-Maud relationship. Poem VI, “His Memories,” and VIII, “Summer and Spring,” allude even more unmistakably to that relationship. In the guise of an anonymous old man, his body “broken,” Yeats can claim, even more graphically than in the poem addressed to Maud’s daughter, “To a Young Girl,” that the relationship with his Helen was sexually consummated. His “arms” may be “like twisted thorn/ And yet there beauty lay”;

The first of all the tribe lay there

And did such pleasure take—

She who had brought great Hector down

And put all Troy to wreck—

That she cried into this ear,

“Strike me if I shriek.”