“I simply wrote stories whenever I got bushwhacked by inspiration and kept my fingers crossed in hopes that in the end they would somehow cohere…” — Steven Heighton

——-

“The writing life, like life in general, has a sacramental and a secretarial side,” Steven Heighton writes. “As years pass and debts and duties accrue, the secretarial, clerical mode spreads like a lymphoma and starts to squeeze life from the sacramental, creative side.” Heighton’s own writing stands in defiance of this clerical mode. Prolific and diverse, he has published more than a dozen books, inlcuding collections of poetry, short stories and essays as well as four novels. He is a writer hell-bent on summoning the sacramental in his ever-expanding body of work, yet one dedicated and disciplined enough to sustain a steady output of consistently superior writing.

Heighton works and lives in Kingston, Ontario. His most recent book is a collection of short stories, The Dead Are More Visible (read my review at Numéro Cinq). In 2011, Heighton released Workbook: memos & dispatches on writing, a lively, eclectic gathering of aphorisms and memos about writing and art. I first encountered his work in the essay “The Admen Move on Lhasa” (from a collection of essays with the same title). This essay remains one of the finest I’ve read on writing and the process of making art.

We exchanged a series of emails over the course of several weeks in preparation for this interview. I confess to some initial nervousness. How often do we get to talk with the people whose work we truly admire? But Heighton was both generous with his time and personable in our exchanges. He asked me about San Diego, about my family and my writing. He confessed to a ‘minor’ bike accident which he described using the term cheese-grater in reference to the skin on right side of his body. He talked about camping with his daughter, about finding a way to earn a living as a writer, about the blazing summer heat and the long, uncertain process of books being optioned to films. (Two of his novels have been optioned recently, Afterlands and Every Lost Country).

This sort of informal formality bleeds over into his writing as well. His stories are accessible but carefully crafted. They are filled with recognizable, often working class characters but written with a meticulous detail for language—a poet’s ear for melody combined with a prose writer’s eye for drama, a sort of genre-bending, cross-pollination of W.S. Merwin and Raymond Carver, Ann Carson and Alice Munro.

Talking to Heighton, I feel myself in the presence of an affable high priest, a hardworking visionary whose polite chit chat is really just clearing the way for what he does best, which turns out to be two distinct things: both writing and talking about writing. The former is obvious; but the latter—the ability to articulate the process, to demystify the act of creativity, is a much rarer thing. Not every succesful and talented writer is able or willing to do this. At times, and especially in Workbook, it feels as if Heighton is lowering a rope ladder down from the Elysian fields and inviting others up. He offers no schmaltzy shortcuts, no write-your-novel-in-a-weekend workshops here. “Interest is never enough. If it doesn’t haunt you, you’ll never write it well. What haunts and obsesses you into writing may, with luck and labour, interest your readers. What merely interests you is sure to bore them.” Haunted is a good word to describe his stories, poems and essays. To read Heighton is to intuit the effort that goes into the creation of something important and lasting. It is to “gape and loiter” in the sacramental, and all the while wonder what it means.

—Richard Farrell

————-

Richard Farrell: Your latest collection of short stories, The Dead Are More Visible, contains eleven stories. Can you talk a bit about how long it took you to gather that collection?

Steven Heigthon: I wrote the eleven stories over a period of six years—2006 to the end of 2011—but during that time I also worked on other things: a novel, a book of poems, and a book of aphorisms & fragmentary essays. I wrote a few other stories as well—stories that my editor, Amanda Lewis, suggested we cull from The Dead Are More Visible on the grounds that they didn’t fit the book tonally. In the end I agreed with her. I’m hoping those orphaned stories will fit into some future collection.

RF: Does making a collection of stories influence the way you write the individual stories? In other words, do you have a thematic sense of where the collection is going before you start, or do you cobble together the book after the stories are written?

SH: In the ’90s I published a book called Flight Paths of the Emperor—a collection of linked stories that use Japan as a point of thematic reference and departure. At a certain point in that book’s making, I did start writing stories with a view to filling in thematic gaps, filling out a larger project. Not so with The Dead Are More Visible. I simply wrote stories whenever I got bushwhacked by inspiration and kept my fingers crossed in hopes that in the end they would somehow cohere, not in an overtly “linked” fashion but through loose tonal kinships imposed by my voice, my angle of vision, the particular mannerisms and mechanisms of my writing.

RF: In “A Right Like Yours,” a female boxer falls in love with her sparring partner. I daresay it’s a love story with a happy ending. I might make an argument that a few other stories in the book have happy endings, or at least resolutions that favor the protagonists. Are happy endings harder to write?

SH: Like any romantic, I have to keep an eye on myself. I want to avoid lapsing into sentiment, avoid poeticizing or aestheticizing the world. So I’ve trained myself to avoid positive endings, or at least prettified endings. With “A Right Like Yours” I took a different approach. I decided to tune out my captious, critical faculty and allow myself to end on a slightly sentimental note. I’m glad I did. It felt like a reprieve, a remission, for me as much as for the main character. There’s a simple sweetness to her voice and I decided not to mute or undercut it at the end.

RF: By contrast, “Journeyman” and “Heart & Arrow” strike me both as particularly sad stories. I’m wondering if the process is different for you.

SH: The female boxer in “A Right Like Yours” is very young. Like anyone, she has experienced a certain amount of loss, but not nearly to the extent that a middle-aged person has. The protagonists of “Journeyman” and “Heart & Arrow” are, respectively, in late and early middle-age—and the tone and point of view of those stories are, in contrast to “A Right Like Yours,” retrospective, elegiac. They’re stories about loss and how we decide what to do with it. But does the writing process differ—is writing a comedy (“comedy” in the classical sense: a story that ends with a wedding instead of a funeral) fundamentally different from writing tragedy? It’s a good question. I guess I’d have to say the process doesn’t differ, if only because the technical demands of writing a story are always the same: keeping it tight, choosing the right words so that each word resounds forward and backward through the text, nailing each physical detail, somehow defibrillating those characters who won’t come to life.

But on second thought: in a “comedy” you can get away with caricatured secondary characters, which makes the process of creation a touch less demanding, and maybe you can also have a bit more fun in writing certain scenes, certain passages of dialogue. But it’s still going to be hard to get the thing right and fictionally true.

RF: Do you ever abandon stories? If so, do those stories haunt you or do you let them go?

SH: I do abandon stories. Do they haunt me after the fact? Rarely. They failed because their material didn’t haunt and obsess me enough during the process of composition. They failed because they lacked the power to haunt in the first place. So I move on to new work and forget them.

But the essence of one jettisoned story stayed with me for years. Around 1992 I started something I called “Nearing the Sea, Superior” and over several drafts it bloated up to thirty pages, and I kept adding more, trying to make it work—like an engineer trying to fix a flying machine that’s too heavy to fly by adding more and more heavy parts. In the end I threw up my hands. Then, a few years ago, I thought I’d take another run at the basic narrative concept—or what I remembered of it. So I searched for a print-out of the original version. Couldn’t find it, and I believe that was a lucky break, because if I’d read that original I might have mined it for a few good details, or lazily used the whole story as a platform for the new version and its protagonist. Instead, I had to take a fresh run at the whole thing. It’s just ten pages long now and, published in The Dead Are More Visible, I think it finally works.

RF: You write novels, stories, poems, essays, and reviews. Do you write all these forms during the same period or do you compartmentalize your writing brains?

SH: During the same period, yes, but usually not on the same day. If the things I’m working on are alive, molten, inclined to flow toward their natural culmination, I can walk away and write something different for a week—say, a review for which I have a deadline—then return to the abandoned thing and, within an hour or two, be back inside the vortex. Partly it’s a matter of sheer curiosity. I never know how my poems or stories will end—I want to write toward my endings with the same interest and excitement I hope readers will feel, reading toward them—so my curiosity about where things will end up helps draw me back into whatever I’m writing.

RF: I recently completed your novel Afterlands, which was terrific. In many ways, it felt like a 400 page poem, yet it was fully articulated as a dramatic story too. Are you a poet who writes novels or a novelist who writes poems?

SH: I think of myself as a writer who channels his narrative impulses into fiction and lyrical impulses into poetry—I don’t write typical “poet’s novels” and I don’t write narrative poetry—but there’s definitely some spillover on the level of language. The thing is, poets like me who also write fiction are saddled with a sensitivity to verbal acoustics. They can’t help lugging their poet’s tool belt into the atelier where they build their stories. So, unlike pure fiction writers, who work stylistically at the level of the sentence, the poet/fiction writer works at the level of the word, even the syllable. Worse, they habitually, helplessly use poetry’s staple technique, re-enactive writing (i.e., the orchestration of verbal rhythm, sound, level of diction, punctuation etc. so that the writing embodies and becomes the action or sensation being described). Bummer. There are ten thousand syllables in the average story and a few hundred thousand in the average novel.

Come to think of it, one of the reasons I’m more and more drawn to narratives that involve physical action and overt dramatic momentum—as with Afterlands—is because I’m hoping those traits will balance the prosodic density of the writing. I don’t want to create 400-page blocks of static, preeningly poetic prose. I’m not writing “re-enactively” to show off—I’m just trying to make my narratives more vivid and vital. So, yes, the poetry is there, but in service to the narrative and the characters.

RF: Is there a style (genre) of writing that feels most natural to you?

SH: Depends on the day. Honestly. Some days I’m a poet, pure and simple. Other days I want to tell a story.

RF: A friend of mine recently told me that she often tries to quietly do ‘beautiful things as an act of defiance.” You quote a Buddhist teacher, Thich Nhat Hahn, who says, “Don’t just do something, sit there.” You’ve indicated that you see the making of art as a defiant or subversive act. Could you expound a bit on this?

SH: Making something slowly and conscientiously, the way you have to build a poem, story or novel, is subversive in the context of a hyperkinetic culture that promotes haste and speciousness—speed and loudness over slowness and quiet, surface over substance. On the other hand, as that second quote suggests, Nhat Hahn extols the importance of sometimes doing no work at all—or at least no material, external work. He too wants people to defy our culture’s manic forward momentum, but by simply sitting, breathing and smiling—“being”—rather than getting too caught up in doing and achieving.

RF: In Workbook you write, “If it doesn’t haunt you, you’ll never write it well.” Do you remember the moment when you first felt haunted?

SH: The truth is I can’t remember a time when I didn’t feel haunted—haunted in the sense of inspired to try to make meaningful things: first drawings and paintings, then poems and stories, and for a while, in my last year of high school and throughout my twenties, songs.

An interesting point about the songwriting. I’ve probably written about a hundred songs and they’re all bad or mediocre except for one, which is pretty good. One good song in three decades. At this rate I’ll have a solid album in about three hundred years.

RF: You bang the drum loudly for the purity of art, for art as a haven apart from the corrupting influences of capitalism and advertising, schlock. But how do you encourage a young writer starting out, who has to pay the bills and feed the kids? How do you advise her or him to stay true to this calling?

SH: Cultivate low material aspirations; you’re going to need them. Remember you can live on a lot less money than consumer culture would have you believe. Abolish all bourgeois vanities about the source and branding of your clothes and other stuff; you can dress yourself decently at a thrift store. Try to find jobs that leave you time to write, real time, three to five hours a day (waiting on tables at night is perfect: decent and quick money, good exercise, and your days stay free). Don’t marry anyone who cares a lot about material comforts and possessions, or who has high ambitions for you. Never marry anyone who doesn’t see your calling as worth a lifetime of effort—and deep down, you know how he or she feels.

[Sheepish addendum: If you have a strong enough constitution, you can produce a stream of books by writing, say, from five to eight every morning before going out to earn a conventional nine-to-five living. I doubt I could do it—manage a tandem twelve-fourteen hour workday on five or six hours’ sleep a night, and with no idling time—but there are people who can. Famously, Laurence Durrell wrote The Alexandria Quartet on the small-hours shift (and I mean small hours—he got up and started writing at three a.m.) before going off to teach schoolchildren. He also managed to make time in that crushing schedule for committed boozing. Stephen Henighan (people are always mixing up our names) is a tenured academic and works on his fiction and non-fiction books in the very early morning, every morning, before going off to teach at the University of Guelph. So that approach is an option for the athletic, the heroic, or persons of Paleolithic toughness.]

RF: I’ve been travelling a bit this summer, and I pay attention to what people are reading. And people are still reading, but sadly, it seems like many people are reading the same few books. (This summer, in particular, it seems the majority of people I’ve seen buried in a book were reading Fifty Shades of Gray.) In Workbook you call lazy readers narcissists. Do you suppose there’s any redeeming value in such group think? From reading anything as opposed to just watching television?

SH: It’s a great question. I guess I’ll say that reading is always different, less passive than TV, more interactive, collaborative, even if you’re reading trafe. And who can blame people for reading trafe? We’re all stressed and scared, one way or another. I fully understand why most readers would prefer an unchallenging, escapist book to The Golden Bowl. (Actually, I think I might find the Shades of Gray series an enormous challenge—which is my way of admitting I haven’t read a word and shouldn’t be commenting on it.)

To get back to that quotation from Workbook. It was part of a three-part “memo” in a section called “On Reading.” I argued in the first part that “Lazy readers are unwilling or unable to empathize with characters different from themselves. Seeking some kind of personal corroboration, they want to read about versions of themselves.” I added that lazy readers are unable to love a work of fiction—or even respect it—if they don’t love the protagonist. Hence my charge of narcissism. I could as easily have accused lazy readers of a failure of empathy, a narrowness of sympathy.

In your question I think you’re addressing a different kind of laziness: the simple need for escape and diversion, which we all share to some extent. Frankly, escapist readers don’t bother me compared to those readers who think of themselves as literary but nevertheless read in the narcissistic way I describe in Workbook. They want to have it both ways. They want to associate themselves with books that look and smellliterary—just as they want to have jazz records, modern paintings, and a decent wine cellar in their home—but they don’t want to read things that actually confront, wobble, even upend their tidy haute-bourgeois vision.

RF: I would use the word prolific to describe you as a writer and the oeuvre of your work. Could you talk about diligence and persistence in terms of your success as a writer?

SH: The prospect of the poorhouse—of failing to support myself and my daughter, then ending up in a rooming house eating Puss ‘n Boots—is a potent creative motivator. I simply lack the luxury of suffering from writer’s block.

RF: In “Heart & Arrow” (which is an absolutely heartbreaking story, lovely, true, haunted), you play with memory as a structural device in the story. The themes of faulty memory appear in Afterlands as well. How important are your memories, both of the real and of the literary variety?

SH: Flannery O’Connor once said (roughly: I’m going on memory here, speaking of memory) that anyone who has reached the age of twelve has enough material to fuel a lifetime of writing. I doubt I was nearly as attentive a child as O’Connor, so probably I didn’t hit that threshold until twenty or so, but I think the point is essentially right. I know that if I concentrate now and revisit some part of my life I haven’t thought of for a while, I’ll quickly locate riches—not because my life has been exceptionally rich in experience or adventure, but because significant stuff is happening to all of us, all the time.

A key thing about the memories we draw on is that time and compound mental revisions have corrupted them—and that’s a good thing for a fiction writer. I travelled through Tibet in 1986 but didn’t start writing about it till twenty years later (in my novel Every Lost Country). Friends asked if I planned to go back, revisit the country, do some on-site research, and I told them no, I couldn’t bear to see how the Chinese occupation had changed Tibet. My rationale was only true to a point. Mainly, I didn’t want my contaminated memories of the place and people to be jarred, readjusted by reality. I was embarking on a novel, not a non-fiction project, and for better or worse the Tibet of my book had to be my version and vision of the place.

RF: You are going to be marooned for the rest of your life on a desert island. You can only take 1 book. What will you take?

SH: You’re not going to let me take a big fat anthology, right? Or the collected works of Shakespeare? Or Proust’s magnum opus, which is really a number of books, a roman fleuve? Fair enough. You want to make it hard for me. I get just one book. So let me spend the next year or two pinning down an answer, because that’s how long it’s going to take me to narrow my longlist of seventy or eighty favourites.

RF: What are you working on now?

SH: For the past year I’ve been working on new poems and stories. Last month I finally got started on a novel, as I have to, since realistically the novel is the only form that can put bread on the table. I think I’ve just finished the first chapter. Now I’ll turn my back on it and work on other things for a few days. When I return to that opening it will either hook me, haul me in and surprise me, in a good way, or leave me cold. If I detect no vital signs, I won’t go on tinkering endlessly the way I used to—a process I now compare to doing chest compressions on an Inca mummy. Nowadays, I just tag the toe and start over.

Thanks for your careful reading and your questions.

— Steven Heighton & Richard Farrell

——————

Steven Heighton is the author of the novel Afterlands, which has appeared in six countries; was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice and a best book of the year selection in ten publications in Canada, the US, and the UK; and has been optioned for film. His first novel, The Shadow Boxer, was a Canadian bestseller and a Publishers’ Weekly book of the year for 2002. Heighton’s fiction and poetry are translated into ten languages; have appeared in London Review of Books, Poetry, Tin House, Brick, London Magazine, TLR, Agni, Numéro Cinq, and Revue Europe; have been internationally anthologised (Best English Stories, Best American Poetry, The Minerva Book of Short Stories, Best Canadian Stories, Modern Canadian Poets); and have been nominated for the Governor General’s Award, the Trillium Award, and Britain’s W.H. Smith Award. He has received the Gerald Lampert Prize, the P.K. Page Award, and four gold National Magazine Awards for fiction. He writes occasional reviews for the New York Times Book Review and in 2013 will be the Mordecai Richler Writer-in-Residence at McGill University.

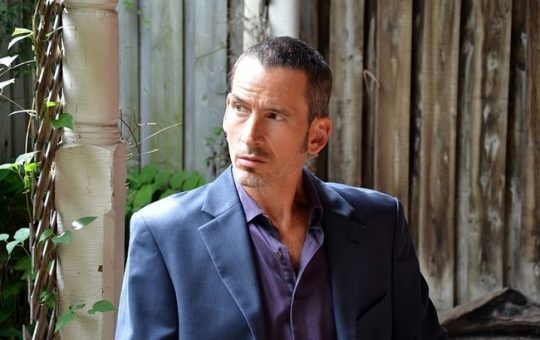

*Author photo credits: Mary Huggard & Michale Lea