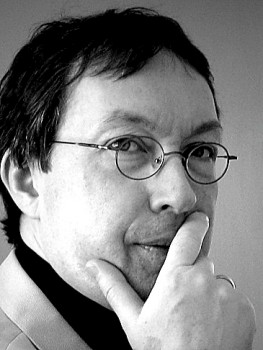

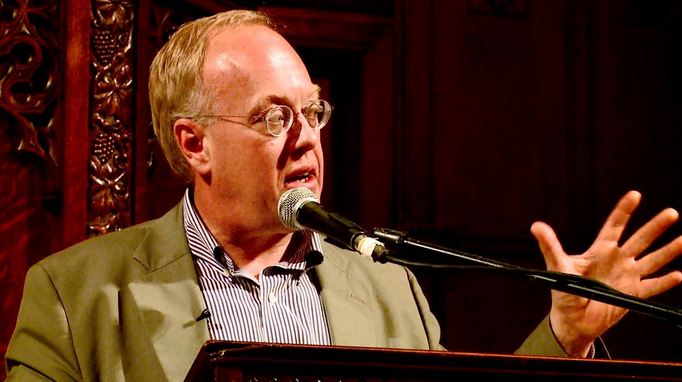

William H. Gass / Michael Lionstar New York Times

William H. Gass / Michael Lionstar New York Times

Eyes

William H. Gass

Knopf, October 2015

Hardback $26.00, 256 pages

ISBN: 978-1101874721

.

Everything is the same except composition.

—Gertrude Stein

William Howard Gass was born in July, 1924, the year Gertrude Stein first published portions of The Making of Americans. In one of many essays about Stein, a writer who became his literary role model and inspired his experiments in composition, Gass writes that the first time he read Three Lives, circa 1948 while a graduate student in philosophy at Cornell, he stayed up all night and that his “stomach held the text in its coils as if I had swallowed the pages.”[1] William H. Gass, newly minted Ph.D., would go on to write over a dozen books composed of sentences the details of which work both symbolically and literally, sentences whose sound and syntax and structure lift worlds from the page.

With a literary career spanning more than half a century, William H. Gass has been praised for his artistry, the beauty of his writing, and the depth of his analytical acumen. He is the author of four novels (including Omensetter’s Luck, The Tunnel, and Middle C), a collection of novellas (Cartesian Sonata), and nine works of nonfiction (including On Being Blue, The World Within the World, and A Temple of Texts). His numerous honors and awards include, among many others, the 1996 American Book Award for The Tunnel, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism (for Tests of Time, Finding a Form, and Habitations of the Word), the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award for Fiction (1975), and in 2000 the PEN/Nabokov award and the PEN/Nabokov Lifetime Achievement award.

For thirty years Gass taught philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, where he has been the David May Distinguished University Professor Emeritus in the Humanities since 2000. His most recent publications include a book of essays, Life Sentences (2012), Middle C in 2013 (winner of the 2015 William Dean Howells Medal), and in October of this year from Knopf, his newest book of fiction, Eyes, a superb collection of two novellas and four short stories. Now ninety-one, he lives in St. Louis with his wife Mary, to whom he has been married since 1952.

Despite the accolades, periodically Gass’s fiction has been accused of being “difficult” or “opaque” in much the same way as the usual postmodern suspects he is associated with, authors such as John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkins, and John Hawkes. Like most artists, Gass dislikes labels, although when pressed, he has called himself a “decayed modernist.”[2] His fiction is language driven, his characters “locales of linguistic energy,”[3] his plots secondary to astonishing metaphorical matrices. When asked about criticism Gass once replied “How can you write well enough to write about Colette?”[4] He’s right. The writing should always speak for itself. For me, discovering Gass was like his discovery of Gertrude Stein the night he read Three Lives. I cannot write well enough to write about William H. Gass; nevertheless, I hope to lure you to trust an artist and master of fiction and explore the world through his eyes.

/

Through a Glass, Darkly

In Camera opens as all the stories in this collection, with its own frontispiece: a black and white “selfie” of the author, possibly from the 1980s, with Gass standing in front of a large storefront window on an urban street. Thus the first image in a story bursting with imagery shows a literal camera, serves as a symbolic representation of the primary theme (our perception of reality), and is a visual pun on himself—a glass Gass. In the background, across the street, is a building with a door of steel panels similar to the steel shutters that protect the shop of Gass’s character Mr. Gab, a collector of vintage photographs—prints by Stieglitz, Atget, Sudek, and many more. The analogy of a camera shutter couldn’t be clearer.

The story is set in the present. Mr. Gab, seventyish, hides out in his shop in a derelict neighborhood where he spends long hours staring at his precious photographic prints. The shop itself becomes the next image, the shop as a camera—the first term for which was “camera obscura,” or “dark chamber,” which is exactly how Mr. Gab’s shop is described, except for the light that leaks through the shutters, projecting the image of shadows on the rear wall, shadows of external objects, objects outside Mr. Gab’s chosen hideaway. And so the images of cameras, photographs, shadows, and projections, begin piling up—all within the first few pages. If the imagery hasn’t been clear, Gass tips the reader to think beyond the surface story he’s telling to its philosophical underpinnings with the clause “but genius was a dark cave full of flickers” and we know we are in Plato’s allegory of the cave.

The seventy-five page novella is divided into four approximately equally long chapters. The third-person point of view uses the indirect internal monologue of Mr. Gab’s assistant (variously named the stupid assistant, you stupid kid, hey-u-stew-pid, u-Stu, Stu, and Mr. Stu in a wonderful progression that parallels the narration of the backstory), but the focalization shifts seamlessly when needed, and through Stu’s thoughts and Mr. Gab’s exposition (and thoughts) we learn how much the photos mean to Mr. Gab; they are his obsession, his raison d’être. The photographs are both for sale and not, as Mr. Gab would prefer to hoard his treasures; however, occasionally he is forced to sell a few prints to make ends meet and he acquires new stock by haggling with shady characters who visit the shop from time to time. His is a cash-only business, and he keeps no receipts so there will be no paper trail.

The stupid assistant, Stu, actually Mr. Gab’s stepson (Mr. Gab “had been his mother’s husband, but was not known to be his father”), is assumed by everyone to be mentally handicapped because of his physical handicaps, which are numerous. Although Stu walks with a limp, has only one good arm, and one good eye—like a camera—he is actually highly intelligent and during the long hours he spends observing the empty shop, perched on his stool like Quasimodo atop Notre Dame, he reads library books, including Walter Pater (another writer famous for his prose style and works on aesthetics, art criticism, and Plato).

During the course of the story, which covers Stu’s history with Mr. Gab, Mr. Gab explains his theory of art and life to Stu using his favorite prints as examples. Gass’s language is so intriguing and beautiful it is difficult to resist the temptation to Google the photos, which are real (at least the ones I looked up), and Mr. Gab’s tone of reverence is pitch perfect, as in this excerpt where he is describing a photograph:

There’s a dark circle protecting the tree and allowing its roots to breathe. And the dark trunk, too, rising to enter its leaves. In a misted distance—see?—a horse-drawn bus, looking like a stagecoach, labeled AI, with its driver and several passengers. In short: we see this part of the world immersed in this part of the world’s weather. But we also see someone seeing it, someone having a feeling about the scene, not merely in a private mood, but responding to just this . . . this . . . and taking in the two trees and the streetlamp’s standard, the carriage, and in particular the faint diagonals of the curb, these sweet formal relations, each submerged in a gray-white realm that’s at the same time someone’s—Alvin Langdon Coburn’s—head.[5] [Gass’s ellipses]

The phrase “in a private mood” works not only in context, but as a metaphor for “in camera,” Latin for the legal term meaning “in chambers” or “in private,” for we are in the most private of chambers imaginable, inside a mind, submerged in a “gray-white realm,” i.e. the gray and white matter of the seer’s brain. This description works metaphorically for the relationship between Gass and his reader as well, with Gass the “someone seeing” a scene and writing it down for us to experience (and don’t forget the frontispiece). Mr. Gab expands on his description, driving home the primary question Gass would have us contemplate:

Such shadows as are here, for instance, in these photographs, are not illusions to be simply sniffed at. Where are the real illusions, u-Stu? They dwell in the eyes and hearts and minds of those in the carriage—yes—greedy to be going to their girl, to their bank, to their business.[6]

Mr. Gab sees the photographers as “saviors” who “bore witness,” each a “stand-in for God . . . who is saying: let there be this sacred light.” The image of God, or gods, is present in all the stories of Eyes and is one of many intertextual links. The religious imagery continues with Stu stealing fruit from the local street market, a metaphor for the forbidden fruit and the tree of knowledge.

Gass once remarked (somewhat flippantly by his admission) that he writes to “indict mankind,”[7] and although that’s hardly the whole story, Gass’s pessimism is conspicuous throughout the collection, as in this example of Mr. Gab’s assessment of the world: “It is misery begetting misery, you bet; it’s meanness making meanness, sure; it’s calamity; it’s cruelty and greed and indifference . . . .”[8] Mr. Gab wants the pure perfection shown in the photograph. For Mr. Gab, the camera is rescuer and redeemer; for him, although the world is “full of pain, full of waste,” through the work of the photographers, “every injustice that the world has done to the world is forgiven.”[9] Stu isn’t so sure. He lives in the outer world, beyond the shop’s shadows, where he walks to and from his flophouse room, exposed before the world’s judging eyes.

Stu stands opposite to Mr. Gab, juxtaposing sun-filled reality with the illusory (though comforting) world of the shop’s shadows. The window in Stu’s flophouse room is unshaded and open all the time, compared with the shuttered shop, and Stu’s single form of recreation is to read (expanding his consciousness) in “sun-filled vacant lots”[10] while the entrance to Mr. Gab’s bedroom (above the shop, i.e. he never leaves) is described as a “hole that was even darker than the inside of a hose.”[11] However, it isn’t so neat and tidy; there is a distinct tension within Stu, the lure of the outside world—a world of color photography—versus his fear of losing the comfort of the concrete world of the shop, not to mention his meager wages. This serves as the story’s plot, as Stu becomes increasingly worried Mr. Gab will be arrested for dealing in stolen photographs. In many ways he wants to stay in the cave with Mr. Gab, and in an ending where the accumulated images culminate in a crescendo as achingly beautiful and sublime as Joyce’s “The Dead,” Stu’s choice is as subtle as a shadow.

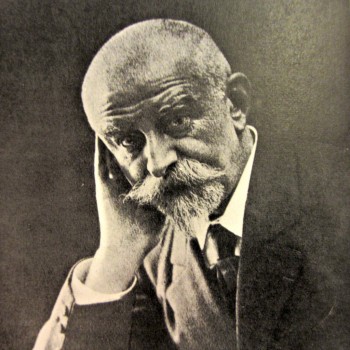

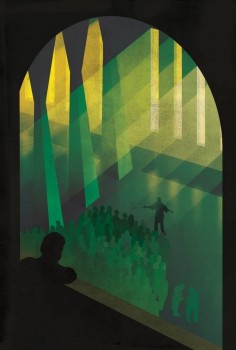

Joseph Sudek, St. Vitus’s Cathedral, 1924-28

Joseph Sudek, St. Vitus’s Cathedral, 1924-28

,

The Giver

The second novella, Charity, presented as a continuous block of text without paragraph indentations, tells the story of a single character, a Washington D.C. lawyer named Hugh Hamilton Hardy and his obsession with being asked for charity. Continuing with Plato’s theory of Forms, the primary theme of the second novella is the Form of the Good. Like the first-person stories “The Toy Chest,” “Soliloquy for a Chair,” and “Don’t Even Try, Sam,” Charity delves into a single character’s consciousness, but here Gass uses a third-person point of view, allowing him to shift between levels of psychic distance and explore a stream of consciousness style. The narrative also shifts in time, cycling (often abruptly) between Hardy’s past and present, and sometimes these shifts can be jarring and force one to reread a sentence or two. The first few pages, in particular, can prove obfuscating in the same way Benjy’s thoughts cycle between past and present during the opening pages of The Sound and the Fury. Gass expects his reader to trust him and move forward, and it is worth the effort.

Despite such speed bumps, the story effectively pulls the reader into Hardy’s consciousness. The style creates a claustrophobic feeling, keeping the reader trapped in Hardy’s mind, where Hardy, of course, is trapped, imprisoned by his feelings of shame and humiliation and guilt, anger and resentment, hating all the beggars and hating himself for his inability to say no. Regarding obsessional characters, Gass said “I want closure, suffocation, the sense that there is nowhere else to go”[12] and this is exactly what he achieves in Charity. On one level, Charity can be read as an inventory of all the people and organizations pleading for his aid. Gass loves a great list, and he indulges his genius for multiplicity, using exaggeration as a rhetorical device to engender in the reader the same frustration Hardy feels upon opening yet another letter that begins “I understand you have helped people like myself in the past.”

As with In Camera, there isn’t a conventional plot, only the rising tension of Hardy’s obsession with giving. Hardy’s obsession is tearing his psyche apart and his work only makes matters worse. His job requires him to travel around the world to various companies who are failing to deliver quality products—either from negligence or fraud—and inform them that unless they fix the problem, huge lawsuits will follow. He’s basically legal muscle, an “enforcer,” and his presence is a de facto threat to force the companies to comply, an ironic parallel with the panhandlers asking him for money.

Hardy works for “Health and Haven”—Haven an allusion to Heaven and God as the ultimate good, the ultimate giver. Hardy sums up his situation:

although I can walk into a Prague or Padua or Paris office and terrify the paperclips simply by saying hello and unsnicking my slick black briefcase, shiny as Mephistopheles’s mirror, I can’t face down a scheming beggar on the street.[13]

The irony of his situation is clear: the big scary lawyer is terrified of panhandlers. Gass creates a wonderful double meaning for paperclips: first, the literal—Hardy is so intimidating that the actual paperclips tremble (and a nice intertextual link to “Soliloquy for a Chair” where all tools are sentient); and second, the metaphorical—that the people Hardy confronts are as witheringly insignificant as paperclips. The simile of Hardy’s briefcase being like a mirror—shiny and clear, something to stand before and be judged guilty—is pushed that extra notch by assigning it to the devil. And that mirror, held up for us too, won’t let Gass escape either, recalling the reflection photograph of Gass (as if in a mirror) that opens In Camera.

Hardy’s continuous internal rant is punctuated by thoughts of Molly, the woman he is dating; their relationship constitutes a subplot. In this excerpt, Gass uses parallel structure (isocolon) to emphasize Hardy’s torment and then segues by association to his thoughts of Molly:

He’d been shaken down at high noon, shaken in full public view, shaken till his change withdrew from an embarrassed pocket and fell out of his crestfallen paw. It was humiliating but she loved to have him lick her like a puppy. Why did he do it? He did it because he was a coward. He did it because she was better at being beautiful than any woman he would ever be likely to know.[14]

Hardy’s mind leaps from “paw” to “puppy,” effecting the transition of his thoughts, but then his thoughts aren’t so clear. Does Hardy’s question apply to Molly, to giving money panhandlers, to both? Gass delays the answer, mimicking how thoughts can overlap. Such mental flights are occasions for Gass to have some fun with transitions, allusions, and imagery. For example:

Hardy would slowly kiss her cute feet: toe one, toe two, toe three . . . She would grow moistly abundant. Resplendent, the thigh skin, stretching away to the mount. He thought just then of the Mount of Olives. Absurd the adventitious bridges between words. Yet it was astonishing how a sacrifice, a catastrophe could comprise a gift.[15] [Gass’s ellipsis]

The sentence about “adventitious bridges” is Hardy’s thought, but it is also a metafictional wink to the reader, a reminder to pay attention and a way for Gass to comment on the possibilities of language. In this passage Gass doubles the image of charity beyond the use of the word “gift”: the Greek for charity is agape, the love associated with brotherly love and the love of God, as opposed to eros, or sexual love. Hardy is capable of the latter, but not the former. The reference to the Mount of Olives and the sentence about sacrifice as a gift brings in the image of Jesus and thus again God as the ultimate giver, and finally, charity is one of the three theological virtues in Christianity, together with faith and hope.

Bad parents run like a scar through much of Gass’s fiction, figuring prominently in The Tunnel, the novella Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s, and in “The Toy Chest.” In Charity, the protagonist’s parents are two of the worst, and the psychology that shaped young Hardy emerges as we learn of their stingy, insincere attempts at charity. During a pivotal episode of Hardy’s childhood, when his parents brought him along on an ill-fated attempt to deliver a box of donated items to a less fortunate family, Gass’s style amplifies the emotional resonance of the scene to such a degree, we cringe and squirm with discomfort. And it is this traumatic memory that will haunt Hardy to his breaking point.

/

The Utes

For Gass, a character can be “any linguistic location in a book toward which a great part of the rest of the text stands as a modifier.”[16] Ideas can be characters. It should come as no surprise then that in the next two stories inanimate objects are the main characters. In the tradition of Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, Gass offers us narrators in the form of a piano and a chair, and if Calvino (of whom Gass is an admirer) can write a convincing story from the point of view of a subatomic particle, Gass can certainly do so with a piece of furniture.

In “Don’t Even Try, Sam,” the piano featured in the 1942 film Casablanca speaks as if being interviewed and regales us with the inside story of this icon of American film. We get all the juicy backstage gossip—fastidiously researched, naturally—and for anyone who has seen the movie, it is obvious which actors (e.g. Beauguy and Miss Visit Stockholm) the piano is speaking about with her distinctly feminine voice. The story begins with a photo from the movie: a dour Rick leaning against the back of the piano as Sam plays, singing, the smiling crowd watching. This twenty-page story is the perfect thematic companion piece to In Camera and uses much of the same imagery. For what is Casablanca but a series of black and white photos? It is Mr. Gab’s stock, only animated—each frame its own collection of shadows, reflections, and glistening eyes, each only a simulacrum of reality. The piano’s grievance with the movie, and by extension, the world, is just this: it’s all a fraud. In the piano’s words: “If this is real life, real life must be a frigging fraud . . . . I go dum diddily dumdum but I don’t feel dum diddily dumdum.”[17] Of course the movie was false, movies are only representations. But the piano’s point is that there were layers of deception. For example, Dooley Wilson (Sam) wasn’t actually playing the piano—nor could he—and thus the title of the story sounds like what the piano might have said to Mr. Wilson during the famous scene when Ilsa asks Sam to play “As Time Goes By,” i.e. “Don’t even try, Sam.”

“Soliloquy for a Chair” is another first-person biography told by an object—a foldable steel chair, named Mr. Middle. The chipper Mr. Middle (named for his placement among a group of seven similar chairs as seen in the opening black and white photo) introduces us to the Mississippi barbershop where he and his six companions have spent most of their lives. We learn he is a member of the race of Utes, who speak Utile or Toolese, for they are descendants of the first tools humans made “Back when the world had meaning.”[18] Mr. Middle’s tale consists of his observations of humanity interwoven with his story of how the barbershop became the target of a mysterious bombing. Gass uses rhyme and meter and sentence structure to engender a whimsical voice for the chair:

It was a friendly place, a little stuffy from piped-in warmth through the winter, but blossoming with habitués at all times of year because, as every person not cursed by baldness knows, hair in plenty grows, through droughts and blights and snows, but not in tidy rows. Not them. Not those.[19]

The philosophical parade continues with the story’s closing sentence (don’t worry, it isn’t a spoiler): “If it suits him in his heart to say it went this way, why not say it went this way, say I.”[20] Mr. Middle is commenting on the belief of Natty Know-it-all (who “got his name by being just the opposite”) that the Utes were the target of the bomber. The phrase “in his heart” implies the opposite of “in his head” (irrational versus logical); likewise “if it suits him” implies an irrational basis for his decision. Mr. Middle grants Natty the permission to believe whatever he wants, and stresses how little he cares with “why not.” If In Camera proposes the existence of an objective world, then this sentence suggests the opposite, and is as succinct as subjectivism can be. Leaving nothing to chance, Gass inverts the syntax, allowing him to end the sentence with “I”—a play on point of view and a pun (a favorite device) on “eye.”

.

A Folktale and a Nightmare

For the frontispiece of “The Man Who Spoke with His Hands,” Gass chose an illustration from William James’s Principles of Psychology that diagrams the neuronal pathways necessary for writing. Sensory information enters through the eye, travels through the occipital lobe to the thalamus and parietal cortex and then motor control is delivered down to a writing hand. The image of the hand figures prominently in the story, and Gass ensures we pay attention for he repeats the title (or slight variations) as the first line in 14 of the first 19 paragraphs. Gass combines this anaphora with his usual rhetorical and lyrical devices to create the tone of a folktale; you can almost hear the missing “Once upon a time” at the beginning.

The narrator of this fifteen-page story is slippery, for although the story reads like a traditional third-person narrative, there are suspicious intrusions of a first-person “I.” The tale is about Arthur Devise, music teacher, widowed father of a college-aged daughter named Dottie, and the man who speaks with his hands—that is, he is constantly making gestures with his hands that don’t necessarily relate to what he may or may not be speaking about. Juxtaposed to Arthur are the other members of the music department, including Professors Rinse and Paltry (names to join the pantheon of such academics as Henry Fielding’s Mr. Thwackum and Mr. Square). The professors speculate extensively on what Arthur’s hand gestures might mean, only to find out that Arthur believes his hands are controlled by God. Paltry discounts this claim as madness and perhaps it is, since Arthur, whose wife was “terribly killed” and who must endure the “nymphomaniacal imposture” of his daughter (who is a student in Paltry’s class) might be suffering from a nervous disorder—which brings us back to William James’s Principles of Psychology. Much is left up for debate and the narrator delivers a barrage of sentences beginning with “perhaps” to close out the last two pages. Once again, the nature of reality is questioned, and the only conclusion is that nothing is certain and reality is subjectively determined.

The last story in the collection is also the darkest. “The Toy Chest” is told in the first person by an unnamed narrator, now an adult, reminiscing about his childhood, his toy chest a Proustian source of involuntary memory. The narrator is agitated, claiming “Today is one of my more lucid days,”[21] and the text is fragmented in places suggesting both a broken typewriter and a fractured mind. Here Gass uses textual spaces as a rhetorical device in a manner reminiscent of his novels Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife and The Tunnel. In fact, the narrator shares many family motifs with Kohler in The Tunnel including an alcoholic mother, a critical father, and an odd aunt. The narrator produced his own newspaper as a child and wrote headlines such as “Death Day Extra” and “Drunken Mother Throws Up At Birthday Party” and as he drops deeper into memory, we are delivered into the solipsism of a single mind’s reality.

l

Worlds Within Words

When asked what he would concentrate on if he were to write an essay on his own work, Gass replied that he would “immediately start talking about the manipulation of language” and that he would “write about writing sentences.”[22] Anyone who has read Gass’s incredible essays knows what we might expect: detailed analysis of the structure of the sentence, spiral diagrams, etc. In the spirit of such an essay, consider the following excerpt from In Camera; it is from Stu’s point of view concerning a certain type of customer:

but occasionally there’d be some otherwise oblivious fellow who would fly to a box, shove off the bag of beans, and begin to finger through the photos as you might hunt through a file, with a haste hope might have further hastened, an air of expectancy that suggested some prior prompting, only to stop and withdraw a sheet suddenly and accompany it to the light of the good lamp in the rear, where he’d begin to examine it first with a studied casualness that seemed more conspiratorial than anything, looking about like a fly about to light before indifferently glancing at the print, until at last, now as intent as a tack, he’d submit to scrutiny each inch with tight white lips, finally following Mr. Gab, who had anticipated the move, through the rug to the card table and the cat in the kitchen, where they’d have what Mr. Gab called, with a pale smile that was nearly not there, a confab.

Concerning cost. This is what his stupid assistant assumed. The meeting would usually end with a sale, a sale that put Mr. Gab in possession of an envelope fat with cash, for he accepted nothing else . . .[23]

The first sentence (199 words including the part not shown) reports movement; it is what Gass would call a “scroll” sentence and describes a journey, a journey the customer takes from his entry into the shop, to the box of photos, to the rear of the shop, and finally to Mr. Gab’s kitchen. We are moving with the customer, and we are going to learn things about the world—including who lives in it—along the way. The sentence’s rhythm modulates as the traveler is either speeding along or stopping to contemplate the scenery.

A clear sound effect comes from the abundant alliteration, for example: “bag / beans / begin,” “hunt / haste hope / hasten,” “prior prompting,” etc., and assonance with “each inch” and “tight white.” Alliteration and assonance can create harmony or dissonance, and Gass uses both. Before the customer becomes “intent,” the alliteration is harmonious, mimicking his movement; however, after “until at last” the alliteration of the sharp ts becomes dissonant. The dissonance symbolically reflects the customer’s mood, his intense scrutiny, his eye attacking each square inch of the photograph. But the effects of Gass’s alliteration don’t stop there, it also affects the tempo of the sentence. Before “finally following” there are sixteen sharp ts beginning with “about to light” and two sharp ks (tack and scrutiny); after “finally following” there are seven sharp ts and seven sharp ks (including the sentence “Concerning cost”). The alliteration of all those stressed ts slows the pace as the buyer is scrutinizing the photograph (pronouncing all those ts slows the reading with almost a tongue-twisting effect). Further slowing the tempo while the customer scrutinizes his prize is the meter. Reading from “a fly about to light,” the meter is iambic until “last,” where there is a natural caesura and a convenient place for a comma. The meter then shifts to dactylic through “submit,” but breaks down between “scrutiny” and “lips” with multiple stresses. There are also caesuras between “submit” and “to” and between “scrutiny” and “each.” If you read this sentence aloud, you must pause, otherwise the words will overlap. Gass is constraining the system for effect, he wants us to move and stop with the customer. “Finally following Mr. Gab” with its easy alliteration and dactylic meter, releases the tension and resumes the forward momentum of the sentence as the customer is once again in motion, now being escorted by Mr. Gab; furthermore, now the sharp “k” sound predominates, symbolic of the location change. At the end of the sentence we have arrived.

Not so fast. It isn’t just sounds that Gass uses to create his effects, there is syntax (reflected in the meter) and structure as well. What about that odd paragraph break? If this were verse, we would call this an enjambment.

Enjambment is characterized by a line break without an end stop where the sentence carries over to a new line for poetic effect, for example for emphasis or surprise. Here Gass uses punctuation and a line break to alter the cadence just as enjambment works in poetry. Even though a period follows “confab,” it is clear this sentence doesn’t really end until after “Concerning cost.” Gass adapts enjambment to slow the cadence once again, to force the reader to pause and dwell on the secret haggling taking place behind the rug curtain. The reader makes a full stop at the period after “confab”; there is a natural pause in shifting to a new paragraph with the line break, and then there is another full stop after the two-word sentence “Concerning cost.”

What about Gass’s choice of words? “Concerning cost” is Stu’s assumption. The enjambment’s emphasis lends a sense of mystery—as if “concerning cost” was a euphemism for bribery or blackmail or theft, i.e. it is a genteel phrase Stu can apply to his master’s actions to maintain the illusion that all’s well and fair and legal and he need not worry about anything. If Gass had written (dreadfully) “About the price,” this effect would have been lost. The word “contraband” is used two sentences later with the same implication. There is also Mr. Gab’s “pale smile that was nearly not there,” which suggests conspiracy and coyness (and parallels the customer’s “tight white lips”), and the word “confab” is euphemistic for something less respectable, less legal. The customer first flies to the box of prints and is then compared to a fly directly—and flies are associated with refuse, carrion, disease. The history of each word becomes a part of the metaphor. Gass’s composition creates a metaphor for the customer’s movement, a metaphor for the customer’s and Stu’s state of mind, and metaphor for the moral character of the customer and Mr. Gab.

Lastly, the second sentence in the second paragraph brings the preceding into focus. This is all Stu’s interpretation, his judgment of what is happening, and where the larger metaphor of the story comes in: Because Stu can’t be certain of what is taking place behind the curtain—he can only assume—we know we are dealing with a question of epistemology, and that is the thematic base of the novella and a theme continued throughout the collection.

René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1928

René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1928

Although each of the stories in Eyes was published separately, the themes and images connect them to produce an eclectic, yet unified whole. Gass’s ideal work of art is a thing in itself, a system of internal relations, and he hasn’t missed many opportunities to integrate these stories. Above all, there is the dominant image of the eye, around which other themes circle like “subordinate suns” according to his description. In Camera is replete with references to eyes, vision, observation, seeing; it is a story about photographs, images captured on film that were focused with eyes for eyes to see. Charity, a novella about a man who suspiciously regards the world, depends on the word “eye” as a verb (and as a noun); and all the stories draw from the definition of “eye” as a point of view, as judgment.

But beyond metaphors, shared themes, and intertextual links, the real quality unifying William H. Gass’s work is the composition, composition born from a belief in the beauty of language, composition that transcends the writing as a thing in itself to become a sublime affirmation.

The frontispiece opposite the title page is a black and white photo of a sculpture called Der Augenturm (The Eye Tower). It looks remarkably like a rocket ship, complete with a passenger sitting in the nose cone, ready for a journey. Marcel Proust wants us to believe that “The only real journey . . . would be to travel not towards new landscapes, but with new eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them can see, or can be . . . .”[24]

Be assured that William H. Gass’s journeys deliver some of the most exceptional views you will ever see.

—Frank Richardson

.

Frank Richardson lives in Houston and received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His poetry has appeared in Black Heart Magazine, The Montucky Review, and Do Not Look At The Sun.

.

.

The Questioner of the Sphinx, Elihu Vedders, 1863

The Questioner of the Sphinx, Elihu Vedders, 1863

Bill Hayward

Bill Hayward Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone)

Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone) Broken Odalisque

Broken Odalisque Al Pacile (from The Human Bible)

Al Pacile (from The Human Bible) Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

Dragon Smoke Behind Tree