My main intention here, anyhow, is simply to say,

Go read the work. — Sydney Lea

Angular Unconformity: The Collected Poems 1970-2014

Don McKay

Goose Lane Editions

584 pages ($45.00)

ISBN 978-0864922403

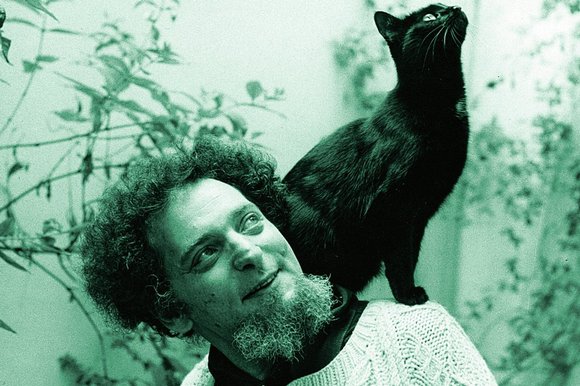

Someone once said of art historian E.H. Gombrich that it seemed pretentious even to praise him. That phrase, whose origin has disappeared from memory, swam back into my ken as I considered the forty-plus years of work contained in Don McKay’s collected poems, Angular Unconformity. While I might not hyperbolize to quite that degree, I do confess to feeling daunted in the face of such unusual achievement as this poet’s, and am somewhat embarrassed that we, his neighbors to the south, seem to know so little of it.

Even if I could adequately consider the whole of this hefty volume, to do so would demand more time, frankly, than I have just now. Though retired, I am all but frantically busy raising funds—against an imminent deadline—to complete a conservation project in a part of Maine dear to my heart. This latest acquisition will be the final tile in a mosaic of protected land—some private, some state, some (in New Brunswick) crown—amounting to 1.4 million acres.

There are many so-called ecological reserves among these holdings. In our own latest case 7100 acres of fabulous wetland are set aside, including a rare domed bog of almost two thousand acres. This zone will be immune from human alteration whatever until the end of time, and will provide nesting and feeding grounds for any number of bird species.

Don McKay, I believe, would approve. Indeed, I first came upon his work over twenty years ago on a visit to Montreal, when I picked up a used copy of his Birding, or Desire (1983), whose principal speaker, like McKay, is an avid amateur ornithologist. (As I indicated in a blog post some time ago, I then unaccountably forgot McKay until lately reminded by another fine Canadian poet, John Lee.)

Not that birds are McKay’s only wild interest. For all its complexity—or perhaps because of it—I highly recommend his philosophical essay collection, Vis à Vis: Field Notes on Poetry & Wilderness (2001), which, far more than I’ll do in this short compass, may provide insights into McKay’s poetics and poetry. Indeed, prior to considering Angular Unconformity, I think it useful to make a brief divagation into Vis à Vis, because McKay increasingly sees himself as one of several fellow Canadian “ecopoets,” keenly attentive both to the natural world and to its crisis in our time.

It’s all very well for the hip, urbanized postmodernists to dismiss such concerns, no matter their own domains will likely be the first and worst to suffer, as appropriate only to bumpkins or sentimentalists. As McKay himself notes in “Baler Twine,” the penetrating initial essay of Vis à Vis, “admitting that you are a nature poet, nowadays, may make you seem something of a fool, as though you’d owned up to being a Sunday painter…. By this time ‘nature’ has been so lavishly oversold that the word immediately invokes several kinds of vacuous piety, ranging from Rin-Tin-Tinism to knee-jerk environmental concerns.”

McKay seeks another path. His acknowledgment of the postmodern stance, however, is crossed by resistance, for reasons that are “merely empirical: before, under, and through the wonderful terrible wrestling with words and music there is a state of mind which I’m calling ‘poetic attention.’ I’m calling it that, though even as I name it I can feel the falsity (and in some way the transgression) of nomination: it’s a sort of readiness, a species of longing which is without the desire to possess, and it does not really wish to be talked about.”

The author distinguishes between his poetic attention and romantic inspiration; in the case of the latter, McKay notes the aptness of the Aeolian harp to the romantic author’s poetry, such poetry yearning for perception to become language. This is less, he points out, a celebration of nature itself than of the creative imagination for its own sake. “Poetic attention,” on the other hand, “is based on a recognition and a valuing of the other’s wilderness; it leads to a work which is not a vestige of the other, but a translation of it.” The author who pays such attention is in search of an awareness released, however incompletely, from the “primordial grasp” involved, say, in building a home; he or she will pay tribute to the wilderness of the other.

No matter its density, Vis à Vis is a joy simply from a stylistic point of view. For example—and I could find scores—“whenever I see (a raven), I feel absurdly gregarious, and often find myself croaking back, hoping it might decide to perch a spell. Yes, there’s a kind of reverence in this. I do imagine receiving wisdom from this creature, but not packaged as wisdom. It’ll come dressed as talk, palaver. And it will have content, unlike, say, the pure lyric of a white-throated sparrow.”

This prose work is not merely to be read; it is to be re-read and re-read. The same can be said, even more emphatically, of Angular Unconformity. I make no claim, as I’ve already conceded, to having considered each of the book’s hundreds of pages: I have, with a sort of willful non-muscularity, roved through it, and I savor the notion that it will always be close at hand, for even to rove here is to encounter abundant pleasure and challenge.

McKay’s “A Note on the Title” defines angular unconformity—savaged as a title term in a smug, self-indulgent, and stupendously wrong-headed rant against the whole book by gadfly Michael Lista (National Post, October ’14)—as “a border between two rock sequences, one lying at a distinct angle to the other, which represents a significant gap—often millions of years—in the geological record… It might also be described as a fissure through which deep time leaks into history and upsets its authority.” The realms that fascinate this poet, then, are so vast and so imponderable that, as in Vis à Vis, no mortal man or woman may dream of containing them, not even in the 554 pages that go into this grand collection.

I mean, therefore, to “review” Angular Unconformity in an entirely unorthodox, even a dilettantish way, but one which may, I hope, indicate certain abiding themes and motifs, not to mention the sustained high quality, of this poet’s oeuvre. Just as if, in fact, the book lay at my bedside, I’ll dip at literal random into portions of the collection, not even responding to every last one, or, in some cases, responding with mere generalities, and ultimately snapping shut in the interest of space.

My main intention here, anyhow, is simply to say, Go read the work.

I preface what follows with a poem from Strike/Slip (2006). In several ways, I believe, it synopsizes a good deal of what I’ve been discussing. The poem’s omni-referentiality, in fact, may account for the publisher’s decision to replicate it on the dust-jacket:

Astonished

Astounded, astonied, astunned, stopped short

and turned toward stone, the moment

filling with its slow

stratified time. Standing there, your face

cratered by its gawk,

you might be the symbol signifying eon.

What are you, empty or pregnant? Somewhere

sediments accumulate on seabeds, seabeds

rear up into mountains, ammonites

fossilize into gems. Are you thinking

or being thought? Cities

as sand dunes, epics

as e-mail. Astonished

you are famous and anonymous, the border

washed out by so soft a thing as weather. Someone

inside you steps from the forest and across the beach

toward the nameless all-dissolving ocean.

Such an utterance, like so many of McKay’s, illustrates (how impoverished a verb!) that radical distinction of poetic attention from Aeolian Harpism, to call it that, in which the natural and the imaginative are presumed to be deeply correspondent—so much so as ultimately to become one. McKay eschews any such notion as Emerson’s “transparent eyeball,” whose possessor dares to say “the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me.” In the moment “translated” by the poem above, otherness is so radically other that it parries even such billowy, Emersonian definitions. True, every “border” is “washed out,” but this leads to no seamless interfusion, to nothing like what Coleridge describes, precisely, in “The Aeolian Harp”:

O the one Life within us and abroad,

Which meets all motion and becomes its soul,

A light in sound, a sound-like power in light,

Rhythm in all thought, and joyance every where…

As one often introduced as a nature poet myself, I equally often hear that I take my inspiration from the natural world. But if I am “inspired” (a term at best equivocal to me anyhow)—if I’m inspired at all, it’s because, like McKay, I contemplate nature as otherness, a dimension in which our fixities and definites are idle, and anthropomorphisms simply Disneyesque. As the poet asks here, “Are you empty or pregnant,” “thinking/or being thought”? And of course these rhetorical questions themselves subside at length into the unanswerable, into “the nameless all-dissolving ocean.”

The trouble is, and none is more aware of it than McKay, the moment we say a thing about that otherness we have at least partially removed ourselves from it. Our “translations,” however hard we try, are always partial and rough. To that extent, the lit-theorists have made much of a truth, usually rendered in inscrutable prose, quite evident to any “nature writer” within the first day of his or her career: as McKay knows full well, to mouth or write the word raven, say, is instantly to depart its mystery for a human construct, to enact what he—again in Vis à Vis—calls our “primordial grasp.”

From this self-evident datum, the theorists elaborate, however variously, perspectives that are ultimately nihilistic. Since the very gesture of articulation compromises some putative, absolute truth, then the world from protozoon to planet is one big carny gig, and absolute truth the silliest sort of pipe dream. The poet, however, or at least the poet who like McKay resists such inclinations, finds beauty and even, yes, meaning in the provisional truth to which he or she is reduced perforce. Wallace Stevens, in a poem aptly called “Of Modern Poetry,” described poetry’s actual subject as “the mind in the act of finding what will suffice.” That nothing will ever suffice entirely is merely a goad to keep trying for that unattainable sufficiency, to write more poems.

I’ve always found it strange that contemporary theory bothers with arguments at all, since those arguments must surely be susceptible of deconstruction themselves; and it’s nearly amusing that it costs so many (cloudy) words to demonstrate the inutility of words. To proceed from that sense of inutility, to go on from insufficiency: that is the mission of so-called creative writing, and not just of the naturalist variety.

Yet of course the natural world is McKay’s principal bailiwick. Notice how he responds, for example, in this excerpt from an early poem in Long Sault (1975” called “Off the Road:”

The kids float sticks

down the creek behind the campsite

while we sip our coffee by the fire.

The moon

hangs over the tent like a neutral traffic light that leaves us

uhh just about to say something that

we don’t–

Dusk is almost better than a word.

I recognize that scene: something as fabulous as the moon may move us to verbal response that, even when lyric or clever or both, seems banal, premised as it is, say, on some simile from our quotidian world, such as “like a neutral traffic light.” It might indeed be the better option, as here, not to “say something” at all, for “Dusk is almost better than a word.”

It is, however, that almost I batten onto, because if dusk—or any other natural phenomenon—were entirely better than a word, then we would have no poetry at all, and in Don McKay’s case, we’d lose something which I’d hate to be deprived of.

I’d be deprived, among other things, of his gift not only as lyric but also as narrative poet. Indeed, had I space, I’d quote sections in many of his volumes that contain marvelous, straightforward prose accounts, which are poetic only in the sense that by his very instincts this author must make them so.

“Along About Then,” again from Long Sault, begins like this:

Along about then this new Mountie, Macmillan,

MacDonald, something like that come down here

Sayin how he’s going to clean up all the stills,

And they was plenty in the township.

…………The others grinning steady, they’ve

…………heard it from uncles or grandfathers

…………in kitchens scrubbed like this one with a Scot’s

…………ferocity…

That is to say that, all through their lives, everyone on hand has heard this story unfold, with various modifications. The cultural studies crowd would call these versions, even the originative one, factitious (or some such), and to that extent, I suppose, lies. But McKay has been exposed to what remains of oral culture in North America. So have I: I know such kitchens or log landings, or campsites, or lumberjacks’ cabins, though in my case the vestiges of those cultures are to be found particularly in northern Maine. McKay is aware that these men (and women?) know the “truth” of a story to be all but irrelevant. What counts is, precisely, its facticity, the degree to which it is a made thing, but one that, almost like a natural organism, has evolved over time and has therefore become, in effect, community property.

It is not the Mountie but the game warden who uncovers the local trade in bootleg booze. The warden walks right up to a deer and touches it, whereupon the animal falls over. Dead drunk.

…old Lalonde and his boys been getting lazy and just

tossed their mash across the fence.

Probably polluted half the game in the township…

Listen to how the poet renders the audience response:

The chuckle’s more a rumble deep down. Everybody

has a sip of beer.

Now the story

will be mulled and tinkered with a rickety

contraption made of names

……………………………..names

……………………………..names like the roads

they cut and stomped and rode…

In recent decades, the very notion of narrative has been viewed with opprobrium by certain scholars, regarded as a vehicle for all the usual suspects (for elitism—no matter the importance of story to all tribal cultures—and racism and colonialism and sexism: ism after ism). Indeed, many a contemporary poet shares that disaffection, for similar reasons or others. And one can’t help thinking that to this poet himself the conversion of experience—especially wilderness experience—to tale-telling is a blasphemy against that revelatory realm that lies beyond words.

But even if they be guilty pleasures for McKay, I, who don’t entirely share such scruples, am happy he makes time to indulge them. His austerer vision is the one for which this poet may remain most remarkable, but praise be, like a health food nut who sneaks to the 7-11 for an occasional Moon Pie, he now and then resorts to this one. Indeed, even in the “new poems” section of Angular Unconformity, and in the latest full volume preceding it, Paroxides (2012), the author persists in including those prose narratives.

The plain fact is that, like an Edward Abbey’s, McKay’s oeuvre exists in an area of tension between his affection for narrative and his propensity toward what is now often called Deep Ecology. The work may stray into one realm now, into the other next, and back again. That’s its very nature.

The volume succeeding Long Sault, it seems to me, explores this tension in a unique way. It is a sustained narrative—which persistently questions the validity of narrative, at least as we understand such a format as westerners. Lependu (1978) is immensely complex, and it would be an insult simply to synopsize, not to mention an impossibility. The historical premise (even if the poem at large pokes holes in the notion of any history that’s authoritative) goes as follows.

In 1829, Cornelius Burley, an illiterate and impoverished citizen of London, Ontario, was convicted of murdering a city constable. He may have been prodded into confession by a Methodist preacher named James Jackson, who may in turn—or so at least McKay insists—have shaped the supposed confession to his own ends, especially a love of publicity. (Jackson read the confession to an assembled crowd and later made it into a handbill, which he sold for considerable profit.) The hanging took place in the courthouse square in the summer of 1830.

A grotesque aspect of the whole affair was that a Yale medical student got ahold of the victim’s skull; a budding phrenologist named Orson Fowler, he displayed it all over North America, showing its various bumps and cracks as indications of Burley’s murderous temperament. What remains of the cranium is now on display in a box at London’s Eldon House, along with other relics.

The poem’s speaker visits that house at the outset of Lependu (French for the hanged man, and the epithet by which McKay usually refers to his protagonist). He sees

Hallways lined with trophies, the skulls and antlers of

………………………………………………………exotic animals:

Hartebeest, Waterbuck, Sable Antelope…

………………………………………………………and (slight pause) Cornelius

Burley.

In “The Confession: notes toward a phrenology of absence,” McKay writes,

Burley, your silence is the wound in our

speech.

We have to climb inside,

into the box we built you, armed with ears

to scavenge and invent…

By way of such scavenging and invention, the poet transforms the pathetic Burley into the mythic Lependu, who comes to epitomize everything in the universe that will not fit into any of our boxes. Various characters throughout the poem, the poet included, will now and then be “inhabited,” however briefly, by his ineffable energy:

When Lependu flu hit Western U

there wasn’t an allusion free from the phlegm

that fell from the air,

Scoffed at profs.

Chalk him not meet blackboard

square but ugh– squawk– sending

shivers of où sont les neiges d’antan

down each individual backbone.

Among other things, Lependu recalls not only a pre-colonial continent (suggested by the pidgin “Chalk him not meet blackboard”) but also a pre-human one. In “Shadow City Shadow City,” the hanged man

lays the absence of his body on the city like a long

black negligee, wakens the buildings

softly, so the bricks remember

being earth.

So in our bones a new

Precambrian weight begins.

The feeling of that weight—which is really a temporary absence of weight—marks, I believe, the typifying moment of McKay’s “poetic attention,” referred to earlier on. Under the influence of Lependu, anyone can experience such moments—and won’t be the same thereafter. There is a prose sector here, for example, called “The Report of an Old Man Whose Life Was Changed After Briefly Becoming Lependu Back in 1946.” The unlikeliness of the title character betokens the omni-availability of these revelations, provided we get out of those boxes of ours; the old man has been on a days-long bender, puking his guts out until “I threw up everything that tied me down… I hung above myself, the zinging moving through like a breeze without a message, asking and making nothing of itself, a time not long but round, still round in my mind when I think back.”

“No message” in the “zinging”—only, as we recall from Vis à Vis, a “readiness, a species of longing which is without the desire to possess.” The prospect of such readiness arises over and over in Lependu. It’s the untying that matters. At poem’s end, the author notes that when the hanged man invades our consciousness,

the only writing is the writing of the glaciers on the rocks

the only thinking is the river slowly

knowing its valley

until the city, seen

in a stutter of light between the branches

nests in the river’s crotch

our own tongues

speaking in a slightly different language and our heads

antlered with images

Now here I am, all these pages later, and I have not even made it halfway through McKay’s collected poems. So I will now accelerate, again with the advisory that anyone interested in contemporary poetry of international importance give this book more time than I can allow myself.

So as I warned, I leap ahead—first, to the volume that caught my attention more than two decades ago, Birding, or Desire (1983). I have spoken of the tension in this poet’s sensibility between an affection for story and an attraction to the natural world’s inarticulable vastness. In Birding…, I think, that tension is especially conspicuous. On one hand, the author is a birder in the Audubon Society sense, field guide in hand, seeking identification, a mark of the desire his alternate title names. (There is erotic desire in this collection too, but I’m scanting that, as so much else, for economy’s sake). Yet he simultaneously longs for the natural domain’s pure otherness. In “A Morning Song,” for example, as he drives to his professorial job, he thinks how

Soon I will be erasing Latin declensions left by the night class

while the dog, sleeping in the kitchen

nurtures my huge laziness in dreams

which are deep and cold

and speckled with uninhabited islands.

The poet has his own Latinisms (in a later collection, for instance, he’ll entitle a poem not “Starling” but “Sturnus Vulgaris”) but his further dreams, like his animal companion’s, are wild and uncatalogued. His “laziness” lies in his sporadic refusals to count and to list. As he says in another entry, “Audubonless/ dream birds thrive…/undocumented citizens of teeming/ terra incognita.”

The urge to document and the longing for pure abandonment to the unspeakable will persist, I suspect, so long as Don McKay writes—a long, long time, I pray—even, or especially given the world’s eco-crisis, in which we

…watch the nesting instinct of the Bald eagle weaken

shells grow thin

its brilliant mind go dim with pesticides.

Let’s tell cuckoo eagle jokes, e.g.

“Why did the cuckoo eagle forget where she laid her eggs?”

Let’s train the kamikaze starlings.

Let’s plan the street map of Necropolis

let’s have statues of everybody.

Let’s learn our own

dead weight.

We may well not recover from such crisis, as McKay suggests all through the poems from 45 years ago to now, and certainly won’t until we gain awareness of that Audubonless world, the world personified by Lependu, or by, for instance, the peregrine falcon in “Identification.” On seeing the bird,

I write it down because of too much sky

because I might have gone on digging the potatoes

never looking up because

I mean to bang this loneliness so speech you

jesus falcon

fix me to my feet and lock me in this

slow sad pocket of awe because

my sinuses, those weary hoses,

have begun to stretch and grow, become

a catacomb my voice

would yodel into stratospheric octaves

……………………………….and because

such clarity is rare and inarticulate as you, o dangerous

endangered species.

The speaker “might have gone on digging the potatoes / never looking up” locked in his quotidianness, which includes the desire to possess. But as I remarked at the outset, the very desire to possess is implicit in the very act of writing things down: this makes for the frustration in the process—

I mean to bang this loneliness so speech you

jesus falcon

fix me to my feet and lock me in this

slow sad pocket of awe….

True clarity, truth itself, exists in a realm as “rare and inarticulate” as the soaring falcon’s. Given such a reality, a lesser mind would retreat into silence, or perhaps into what I’ve called the nihilism of many recent literary commentators. McKay knows that an utterance adequate to the monumental world of nature, or perhaps to any world, is beyond him. But he moves on from such awareness of insufficiency. He does so not altogether happily, though we as readers should be more than happy for his persistence.

— Sydney Lea

Sydney Lea is Poet Laureate of Vermont. He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. His poetry collection Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Another collection, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner. His 1994 collection of naturalist essays, Hunting the Whole Way Home, was re-issued in paper by the Lyons Press in 2003. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont College of Fine Arts and Middlebury College, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in September, and Skyhorse Publications just released A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife. His eleventh poetry collection, I Was Thinking of Beauty, was published in 2013 by Four Way Books.

.