Bojan Louis reading.

Bojan Louis reading.

.

.

As long as he stayed ahead of the project manager’s bullshit for the next two days Phillip George could have the weekend to take Jared, his older cousin’s son abandoned to him, to the base of Mt. Elden, where unconnected caves offered refuge and seclusion to both amorous teenagers and the homeless transient. The kid had been cutting bat shapes—since a unit about volcanoes, caves, and bats in his gifted second grade class—from the delicate pages of the Bible he’d found in the dresser drawer of the weekly/monthly motel. Phillip’s health-major-minded girlfriend had protested that the distance might be too far for the kid’s physical and mental capabilities, no thanks to his down syndrome. But Phillip was intent on nothing obstructing his plans.

His shift ended after another twelve-hours and a call from his project manager asking him to remember to lock the gate to the job site, which he did every day since he always left last. Vick was a knew-enough-to-be-dangerous construction lackey turned PM, probably because he was the general contractor’s relative or a favor owed to a friend. He arrived to job sites in his overly chromed and small-dick lifted Ford F-350; clean shirt tucked into ironed jeans, boots more shiny than used, holding a clipboard of meaningless to-dos and a list of places where he’d eaten lunch and with whom. He was the perfect middleman between the GC and clients/investors for his readied knowledge of available tee-times and recipes for wine spritzes.

While Phillip chained and locked the gate he imagined Vick yammering among clients and contractors his annoyances regarding employees, the rising price of material, and the perpetual failure of other sub-contractors meeting deadlines. Shit-talk that made the workers seem like ignorant numbskulls, though most actually were, Phillip included. Without a false sense of dignity there was no assurance that what the clients and contractors paid for was actually hard work or craftsmanship, but projects completed just good enough.

When Phillip secured the site at the end of the day he rode the bus home, glared at his reflection in the opposite window; the florescent lights making him ashen, his negative-like image superimposed with dated storefronts the bus rumbled passed. He dozed, tried to ignore the lurch from potholes left after winter storms, and the conversations crackling around him.

§

The dusk sun left the clouded and smoke filled sky a flare of fire as Phillip side-stepped puddles and runs of mud on his walk across the parking lot of the Elden Motor Inn to the office. Inside the heavy glass door he set down his tool bucket and drill bag, rang the bell like he’d done every week for the past few months.

The motel owner/manager appeared in his typical collared rayon shirt rolled to his knotty elbows, a brightly patterned tie, and tight Wranglers stretched painfully over his large and well-sat ass. Boots, fashioned out of ostrich skin, creaked and clopped as he positioned himself behind the front desk. He often wore a white cowboy hat, but today he appeared with black hair bushed on top of his head.

“You just missed the hura cabrón,” he said. “Rolled out of here ten minutes ago.”

“No shit,” said Phillip. “Saw a couple cruisers from the bus on the way in. What was it? A little domestic violence, meth-heads exposing their freaky fucked up nature?”

“None of that, ese. Just the locotes from 1A and 2D arguing and coming to a half-assed fistfight over going halfies on the last bachita and who hot-boxed it. Pinche borrachos. You’d think they die of agua or straight oxygen.”

Phillip nodded. More of the same down and out, struggling to keep one’s head above water bullshit; generally meaningless and harmless, though as consistent and disheartening as shirked overtime pay. He slid two hundred seventy over to the manager who pressed his tree trunk like fingers on the crinkled bills until Phillip released them so that he could pocket the money. Phillip never saw him use the register or any sort of record book. The couple times he asked for a receipt the manager simply pulled a notepad from behind the counter, wrote the name of the motel, the date, Phillip’s name, the amount paid, and scrawled figures resembling a T and M; all an act of show, nothing official or legit.

“That chica of yours not being too hard on your pockets, hombre?” asked the manager.

“No,” said Phillip, “she’s too busy keeping her head in her books and fucking exercising. What makes you say that?”

The manager shrugged, tongued at something between his teeth, and opened his mouth to say more but didn’t. Phillip palmed the counter, waited for whatever might be said next.

“Well, hombre, just before the hura got here I found your niño playing around back, close to the basura. Nothing to stress about, I took him back to your pad. The puerta wasn’t locked and your chica was laid out cold, snoring on the bed. Don’t worry, ese, I didn’t see her tetas o coño. She had on one of those fantasía track suits.”

“Fucking hell,” said Phillip.

The evening reds had faded, the night air warm but cooling. Many of the other tenants had their doors open, the noise of reality television mixed with the dying traffic on Route 66. Phillip’s tool bucket and drill bag banged against his numbed calves, his shoulders felt as if nearly pulled from the socket. The single window of his room glowed at the edges of the drawn curtains. His eyes itched and watered slightly from the ever-present smoke of the first series of controlled burns. It was still early in the fire season, but he and the rest of town hoped a substantial monsoon might dispel the previous decade of drought.

§

Before Phillip moved into the Elden Motor Inn his lady, Benita, was living in the dorms at the university, which was required of freshman that didn’t already live in town. They’d dated a year long distance by then. He’d worked for a commercial electric company that landed most of its contracts with another company that built resort hotels in and around Phoenix. A large and temporary employee pool assured him work for no less than six months and also the knowledge he’d be laid off once a certain phase of the work was completed. He never saw the resorts in their final glory, never got the job to finish or trim-out the receptacles, light switches, or lighting fixtures. He only bent and secured what felt like miles of half-inch to two-inch conduit, pulled circuit-boats to and through junction boxes, and made-up and readied the wires for the eventual installation of chandeliers, sconces, dedicated circuits, and smart-dimmers. His work was invisible, necessary that it work the first time with nothing to troubleshoot once the main power was turned on. He would hump a slow Greyhound north every other weekend to visit Benita, play stow-away in her dorm room, flip idly through her textbooks while she studied and he waited for sex or a meal. It all seemed perfect. Fucking, eating, fidgeting through movies, and being asked to parties, since he had five years on her, where she drank drinks called skinny-something-or-others. The calorie count so low she could indulge in one or two, three maybe. She was consistently counting and calculating: calories, miles, reps, fat percentages, heart rates, cholesterol levels, grade point averages. Her major’s focus was on obesity and diabetes in Navajo communities, the lack of education in regards to healthy eating, and dispelling the myth of fry bread, which she told him was a significant health hazard due to its high calorie content. Fry bread was, in effect, a remnant of colonization and forced removal, The Long Walk. All of which he could understand though at the end of his long workdays could give a shit about.

When Phillip entered his one room domicile he found Benita snoring open-mouthed on her back, hands clasped death-like over her stomach. He grabbed her leg and shook. Her limp body moved as if her joints were loose. This incensed his anger, made him shake her violently until she woke.

“You can’t stay awake another hour to keep an eye on the kid?”

“What?” she asked drawing out the vowel. “Don’t shake me like that. I’m not some wasted, passed out ‘adláanii.”

He let go her leg, removed his hoodie and t-shirt, threw both toward the clothes piled beneath the sink outside the bathroom, and attempted to pull off one of his steel-toe work boots, which he didn’t unlace completely. It nearly hit him in the face once free and he shouted fuck, threw it against the wall, and got a muffled yell and pounding in response. While he fussed with the other boot Benita said she’d wanted to fit in a Body Pump class before picking up Jared from after school daycare. This was a tension grown between them; her poor time management and agreeing to get the kid no later than five so he wouldn’t risk losing overtime. There was no one affordable to look after the kid no matter how much overtime he worked. And anyway, who would want to look after a nine-year-old with down syndrome whose trust in strangers was lacking at best and who also took issue with anyone other than Phillip touching the back of his neck or ears?

“Jared was asleep and I locked the door. I thought we’d both nap until you got back. He’s never done anything like this before. Never wandered out alone. It’s something to pay attention to from now on. It won’t happen again.”

She faced him and smoothed her green warm-up top, curves tight beneath the soft, plushy material. Fuck his anger, he thought, and hoped she would turn away from him so he could see her from behind, approach and press his tired body to hers, caress the firmness between her breast and thighs.

“Fucking shit. You know the manager found him playing in the trash around back? What if those cops from earlier found him? Deep shit. We’d be in deep shit. Hell, his mom already fucked him over. We don’t need to, too. Even if it’s . . . because one of us fucks up.”

She turned, awaited embrace and apology, and blamed final semester stress and the need to carve out time to care for herself.

The argument waned and Jared, hunkered quietly beneath the round two-chair table next to the window, called out hello. Strange how he became invisible, thought Phillip, despite being what occupied his mind and energies most. Maybe that’s how he escaped earlier. His presence demanded all of one’s faculties, yet he could vanish and still seem to be all places.

“Hey, little man, I’m sorry. We didn’t mean to yell so much.”

The kid emerged from beneath the table to hug Phillip, a hug that forced the breathe from him. He wondered if the kid would ever become strong enough to crack his ribs.

“I’m cool, man. I’m cool, man,” he said.

Sure that Jared hadn’t been in any real danger, and the manager was a person who he could count on, though he’d never make it a thing between them, Phillip reassured himself by lightly squeezing Jared’s shoulder, and headed toward the bathroom.

“You need to pee or anything? Or is there some business that you need to finish before the weekend?” he said over his shoulder.

“I don’t need to go. I’ve got bat business.”

While Jared returned to his task Benita sat facing the opposite direction sobbing. Rather than reengage the argument they were having, or about to have, Phillip asked if she could keep an eye on the kid. She acknowledged by looking toward Jared, who waved at her. She waved in response and turned the TV on.

In the shower, Phillip imagined his life differently. His final years of high school and not quitting the club soccer team before a couple of college scouts had taken the time to watch a few matches, offer scholarships to a handful of players. Had Phillip stayed it was likely that he would have been one of the guys selected to play with a full ride to one of the state universities or, at the very least, a community college. Had he stayed he would have gone. From there was a life he never fully envisioned. Pro, semi-pro? Would he have finished his degree? Would he have had a major? Construction management or hotel and restaurant management? Something that required little academic vitality but with the potential to have made him more money than electrical work? Would he have dated Benita, or some sorority blonde who’d he fuck how and whenever he wanted? He most definitely wouldn’t have honed in on the young Benita giving him eyes; he the potential bad boy, though the truth was that he was the best thing for her. Stable, mature, and in no way related by clan. But there he was living check to check, with an abandoned retard, and a girlfriend who would probably leave him once he got fatter, once she found her dream job after she graduated. There he was, beholden to everyone else with the soap and hot water rinsing off the grim of another fucking day and maybe, more of him.

Relieved with clean he slid open the shower curtain, found Benita leaning naked against the door, her clothes piled neatly in the corner. He hadn’t heard her enter, so deep in his own head as he’d been. Her brown figure had toned up in the past couple of months. Her hair lay in black strands across her small breasts. He felt himself get hard.

“You’re leaving him alone again,” he said.

“That’s what’s special about you. You never think of yourself first.”

She grabbed a towel, dabbed his body, and used it to soak up clumps of his wet hair. She frowned, whispered that the kid was occupied with his bats; she would pay more attention later. He kept quiet, didn’t want the momentum to be lost, and guided her to the top of the toilet tank, lifted her leg, slowly pressed into her. He’d go to bed hungry: exhaustion and an apology his dinner.

§

He dreamed of volcanoes erupting suddenly, all at once. The town was the town he lived in but different, spread out with houses overlooking cliffs that didn’t exist. Lava poured from the angry cones, fire ash fell from above, and cracks opened the earth. Escape wasn’t likely. On a strip of land he watched the black sky descend; heat beneath and around consuming him.

At 4:30am, startled from the dream, he staggered to the bathroom to piss, began to dress. Work pants from the day before, a fresh t-shirt, and a collard button down. Back in the single-room he kneeled over Jared, woke him by smoothing his hair.

After the kid was showered and readied he took Benita’s keys from her purse and drove him, half-awake staring out the window, to his elementary school.

“Hey, kid,” he said poking him, “before we get you to school tell me what you’re going to tell the bats when we find them.”

“I love them being my friends,” he mumbled. “What will you tell them?”

Phillip wasn’t sure, but maybe something about how he appreciated the bats being Jared’s friend. He added that he thought it’d be a good idea if Jared brought along the bats he’d been making so that his bats and the bats supposedly in the caves at the mountain base might become friends, too. The kid told him, duh, that was why he’d been cutting them out.

Benita was never awake when he returned her car in the mornings. Wouldn’t even stir if he bumped the furniture or creaked the door open and closed. Girl can sleep through anything, he thought. A quality he both admired, looked down at.

He retrieved his tool-bucket and drill bag, walked the two hundred yards to the bus stop that took him across town. Every day the same ride: sparse traffic; chemical white billows above the toilet paper plant south of the train tracks; an abandoned steel mill turned junkyard that advertised auto-repair and estimates; the refurbished historic downtown beyond his price range.

At twenty past seven he arrived to the job site where Vick waited to tell him he was late.

“I’m this late every day,” said Phillip. “I don’t control the bus schedule and you can’t get me a ride, or anyone else, here on time. I’ve got the kid to take care of and there’s no use jerking off here before seven if the gate isn’t even open.”

Vick waved him off, muttered yeah, yeah, even though none of the other trades ever arrived before eight, and if they did it was always to stroll around with donuts then fuck off for the day. Phillip was the only electrician onsite; reliable, his lack of a vehicle the assurance he’d stay put, and still he’d never been given a key to the gate.

While Phillip unchained and positioned the ladders, Vick brushed the rat end of his ponytail against his lips and examined the conduit runs across the ceiling; traced each run to where they ended at the service panel or hung unfinished.

“Might get close to finishing the runs today,” said Vick. “If you can hustle and don’t fuck up. How are you on materials?”

Phillip needed spools of ground and neutral wire to begin pulling circuit boats by the end of the day, and asked if he could get off early, hoping Vick wouldn’t put too much thought to it. Vick sucked the tip of his rattail, took more than a minute to respond. Wouldn’t be possible. Not with all the added dedicated circuits, subpanel, phone, co-ax, and ethernet for the reception area, break room, and bathrooms. The facility was going to be top of the line, which meant as much distraction as possible. The patients would want to ignore the fact that they were in a dialysis center. There would even be TVs in the pisser. All overtime for the week and, Phillip suspected, through the weekend. He reminded Vick that he’d requested time off, who responded that it was out his hands. But with Phillip’s request in mind—which was bullshit—Vick had hired a helper; older guy who claimed ten years residential wiring experience and countless skills in other trades.

“Sure, that’s all a load of shit,” said Phillip.

“That’s what I’m thinking. But he’s got no qualms working for ten an hour without overtime despite the experience he claims to have. Shit, if he were a Mexican I could pay him seven. Anyway, you’ll probably have to teach him to bend pipe, pull wire, and whatever else. You’re going to have your work cut out for you. And I don’t imagine he’ll be too keen on a young tonto telling him what to do. Guy’s name is Nolen or something. Told him to show up around nine. Give you time to set up and get going. I should have your material here by then.”

Vick spat a loogie on the polished concrete floor, smeared it with the toe of his boot, and walked to his truck.

After he drove away Phillip cursed him for being an inept and ignorant piece of shit who had managed to fuck him by hiring some old lackey, probably a drunk if he possessed no real skill, who would only slow Phillip’s progress. Just another benign action from the managers that reminded Phillip of his unappreciated and unacknowledged skill being a reliable electrician who made twelve to the ten dollars an hour that his helper was going to be paid.

Around nine-thirty Phillip smelled the sour stench of cigarette smoke and days old body odor. He turned, looked down from the twelve-foot ladder he was working off of at a man, probably six-six, wearing clothes that hung off him like the tattered sails of a ghost ship. The man clomped across the job site in large desert boots, reached into what remained of a shirt pocket for a pack of cheap cigarettes, lit one using the one he’d smoked to the filter, and flicked it behind him aimlessly.

Phillip descended the ladder, uncertain if this was the guy Vick had hired or a random homeless.

“Can I help you with something?” he asked.

“That’s what I’m for,” said the man, “to help you.”

“All right. Vick said your name was Nolen? I’m Phillip.”

The man shook his head.

“It’s No-Lee,” he said.

Phillip watched him and the man explained that people always asked if he had any leads on any jobs and he’d tell them no, no leads. So the name No-Lee stuck. The two stared at one another quietly until Phillip told No-Lee that he would start him on running conduit. They’d work together until No-Lee got the hang of it; it’d be easy since they were only using half-inch, a little three-quarter.

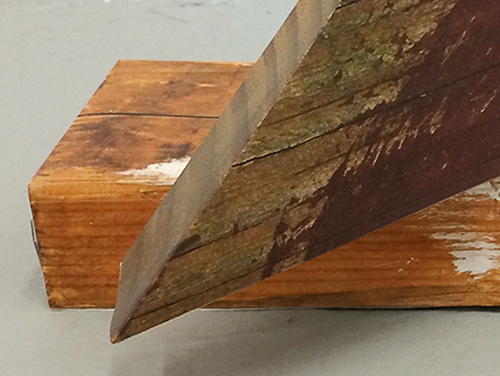

They worked atop ladders eight feet apart, the length of a single stick of conduit. At the butting end, No-Lee tightened the coupling with channel locks and secured the conduit to the base of a wooden truss with a half-inch strap, eight inches from the coupling. Phillip held the opposite end, measured off the wall to assure a straight run, and strapped the conduit loosely. They moved across the truss work in leapfrog fashion until they reached a point in the run that required a ninety-degree bend toward the service panel. Phillip explained the fundamentals of conduit bending: from the point of measurement mark back five inches, toward the dumb-end of the tape—six inches if using three-quarter—make sure the foot pad of the conduit bender faces the foot; make sure the bend is a perfect ninety by applying equal pressure on the foot pad and handle, and use a level to be precise.

No-Lee repeated the instructions and the work continued smoothly, faster than expected.

They took lunch at two. Phillip estimated that they’d accomplished a little more than the day’s anticipated work. Two more days working like this past sundown and he would have Saturday secured. While he jogged to the corner gas station, No-Lee sat where the breeze was strongest and smoked, eyes closed as if gathering substance from the tobacco and wind. Phillip returned with a microwave burrito, a bag of dollar chips, a gallon of water, and sat far from the rancid breeze.

“You eat that shit every day?” asked No-Lee.

“It’s cheap,” said Phillip. “I don’t have time to make lunch. I’ve got the kid I take care of. Eats up most my time.”

“You got a kid?”

“Not mine. My cousin’s. I raise him here so that he can go to a decent school, have more opportunity or whatever.”

“Mother drink herself to death, huh?”

Phillip crumpled his burrito wrapper, threw it to where it suspended for a second, and was blown backwards.

He was used to this passive-aggressive, not uncommonly aggressive, shit talk from white, conservative co-workers and bosses. Back in Phoenix was the worst ignorance he’d encountered. It was everywhere, as much as there was heat and blowing dirt. Proud right-wingers who boasted about the guns kept locked in their glove boxes, some with handguns strapped to their hips, talking God and country, rights, and who deserved to live and who to die. Sad harbingers of death that Phillip could only do his best to ignore, though he was often confronted because he was brown, mistaken for being Mexican, and always given a pass because he wasn’t them, but neither was he an us.

“None in my family drink,” he said. “The kid’s mom fucked off to Portland with a bunch of vortex, vision-questing dykes.”

No-Lee drew long and the cigarette ember flexed; dragon smoke fell out of his nostrils.

“Bitch can’t appreciate her own dying culture. Funny. All that pride you redskins powwow about and most of you fall for New Age bullshit. You sell out your faith then build fucking casinos.”

Phillip ate his last chip, dropped the bag. He rose, told his helper to sit and smoke for the rest of the lunch hour while he got back to it. No-Lee responded, I work when you work, and was told to clean up. He stood, examined the job site, which was clean except for some unusable scraps of conduit and the trash Phillip had tossed. No-Lee picked up the burrito wrapper and chip bag, stuffed them into his pocket, and organized the material without comment; his only noise the exhalation of smoke and the gurgled hack of clearing his throat.

Phillip called the day sometime after seven, watched No-Lee walk east beneath streetlights until he became a burnt match in the distance. He made note of the next day’s work—pull boats, pull lighting circuits, low volt, land the panel—grabbed his gear, and trudged to the bus stop.

§

He arrived back to his place late. It sat dark, still between the noisy brightness of the rooms on either side. The curious tunnel of it drew him in. Benita had left a folded note. The explanation was simple: she was tired, needed to consider herself and her final semester, had left Jared with the manager. Anger shook Phillip’s throat and he punched a hole in the wall, smashed one of the two chairs. On his way to the manager’s office he gathered himself by tapping his chest imagining he and the kid excited, out of breath before the mouth of a cave. They’d enter a cool damp darkness; shine lights on walls that held something he couldn’t think of. In the office, Jared and the manager watched a cartoon show Phillip didn’t recognize. Their laughter settled the tension in his shoulders and he watched for a few minutes before announcing himself. It wasn’t a big thing for the manager, since Phillip hadn’t ever been a problem, but it also couldn’t keep happening. Phillip needed to figure it out.

Back in the room he and Jared continued watching the cartoon until both dozed and slept, their shadows playing oddly on the wall behind them.

§

The morning bus that took Phillip and the kid to a stop a quarter mile walk from his school was empty. At the school, they waited until the doors opened for students who needed an early drop off. Before entering, the kid told Phillip that Benita would come back, she’d cried before taking him to the manager’s office. The kid was probably right, Phillip told him. They’d have a boy’s weekend and everything would be the same afterwards.

At the job site, No-Lee sat against the locked gate smoking, said there hadn’t been hide or hair of Vick. It was close to eight. Phillip made the decision to dismantle the tension bands so that the chain-link fence fell slack and the two could crouch down and through. Let Vick fix the goddamned thing; they needed to get to work. When Vick arrived after lunch he shouted at Phillip for fucking up the fence, went on about added cost and time. But the fence wasn’t damaged, only taken apart, and if Vick actually knew anything, he could reassemble it. In response, Vick threatened to fire Phillip, who packed up his tools and walked out the gate, where he was stopped, told to calm down, and asked what was needed in order to fix the fencing. Phillip told Vick that No-Lee knew. So, the two of them reassembled the tension bands, spoke quietly, and looked and nodded toward Phillip.

Before the day’s light began to fade Phillip told No-Lee that he needed to leave to pick up and return with the kid.

“You work late Fridays?” No-Lee asked.

“Twelve to fourteen is average. I don’t care if we to work all night. We’re getting this shit done.”

“Whatever you say,” said No-Lee. “I’ve got my cash in hand. See you when you get back.”

It took an hour to get the kid and what remained of daylight when they returned cast deep shadows throughout the interior of the job site. The gate was locked and from what Phillip could tell from behind the cold links the ladders had been left standing. Since he’d left his tools behind he told the kid to wait while he jumped the fence. Inside the unfinished building material was strewn about, his tools gone, along with a couple spools of solid wire.

Phillip dropped to his knees, held his head between them, and screamed into his shirt. No-Lee had probably been waiting for a moment when Phillip lent him any modicum of trust, so that he could leave him fucked. No regard for his livelihood, his need to care for himself and the kid. He dialed Vick, got voicemail immediately. Piece of shit had already disappeared into the weekend, obviously hadn’t even returned to check on the site.

He stood, a friction among the shadows, and threw his phone against the polished concrete, its shattered pieces skipping outward. He turned and jumped the fence once again, told the kid, to hell with it, it’s all fucked, and took his hand to walk to the gas station for a couple dinner burritos and provisions for their trek to the cave come morning.

§

The kid didn’t fuck around. He sat in the unbroken chair gazing out the window at thunderheads separated by cuts of sunlight that spotlighted down making dew of the predawn rain. Phillip snored on the bed, a pillow over his head. It was well past the time they’d planned to depart. The kid slid off his chair, opened the door: crisp, cool scent of vanilla from the ponderosas and the dusty mold of the morning’s moisture engulfed the room. Phillip stirred, woke to see Jared dressed, his pile of cutout bats ready on the table.

He rubbed his puffy face. “Guess I better get my lazy ass in gear, huh? Let me shower and we’ll get the hell out of here.”

The kid nodded, shut the door. He gathered the bottles of water, granola bars, and two Snickers that Phillip had bought. He took the flashlight kept in the nightstand drawer, located both his and Phillip’s bus passes. Everything was ready.

The trailhead lay northwest of them, the nearest bus stop next to a grocery store a half-mile walk away where Phillip lifted two oranges from an outside display of produce. He told the kid they needed to survive and they continued their trek. Beneath the shade of large ponderosas they paused to drink water. Phillip asked the kid if he was hanging in there ok, there was a mile and a half left to go. The kid said he was fine; they’d go on, they’d survive. The two pushed forward and the day warmed up, a little humid from the morning’s rain. Phillip felt the hardened shell of his heel crack, the tender flesh beneath sticking to his sock, which slowed his pace. The kid noticed, told Phillip there was no need to rush, the bats would be there. They stopped once more where the tree line broke into a clear cut for a natural gas pipeline and service road. Logs were piled into long triangles about twenty feet away from the treed edge, the brush cleared for when fire crews would come to complete controlled burns. Across the road the trail inclined into the shade of the ponderosas.

The mountain base was a jumble of volcanic boulders and hardened lava flows that created climbing opportunities, as well as, shelter in the caves and dead-end tunnels. Lichen, an assortment of small trees, ferns, and cacti covered the unreachable parts, higher up on the rocky ledges. The cover of tall ponderosa pines made the day appear later than it actually was. Phillip and the kid walked the base, went off trail to where a cluster of ferns grew, and came upon a small, man-sized entrance into the rocks. Phillip suggested they eat before entering. The kid ate quickly, reached into his pocket for his pile of bats, peeled one off, and handed it to Phillip, asked him to read its body.

“It just looks like notes from the bottom of the pages,” said Phillip. “This bat must be a nerd. Hand me a different one.”

The kid laughed, set the bat in what he deemed the nerd pile, and peeled another off.

“Let’s see, it says ‘11 Again, if two lie together, then they have heat: but how can one be warm alone? 12 And if one prevail against him, two shall withstand him; and a threefold cord is not quickly broken. 13 Better is a poor and wise child than an old and foolish king, who will no more be admonished.’ Damn, kid, these Bible bats are fucking intense. Let’s see one more.”

The kid off peeled bat after bat while Phillip read the bodies. The pile wasn’t substantial, but since Jared had worked slowly and meticulously cutting them out, Phillip was proud of his handiwork.

Some dexterity was required of the entrance, though the squeeze of it wasn’t tight. Cool air exuded the rancid stench of piss, body odor, and alcohol. Water trickled somewhere in the darkness. Once inside and on flat ground Phillip flicked on the flashlight the kid had brought, shined it toward the sound of the water. A figure, more detritus than man, wavered cock-in-hand, pissing against the far wall.

“You gonna come suck this thing or fuck off with that light?”

No-Lee’s smoke and drink broken voice. He’d been drinking all night, all morning; face a grotesque swell of skin.

Phillip panicked, more for the kid’s safety than his own, and hurried to push Jared back from fully entering the cave, but the kid tumbled off the rocks and in, yelped painfully, and lay holding his ankle in the faint light of the entrance. Phillip knelt to urge the kid up, didn’t see the spool of neutral wire thrown through the darkness. He felt the hard weight strike his temple, swirled into the void of his volcano dreams: pools and rivers of lava, the burning of his face and body, the burning of Jared and Benita’s bodies, screaming and laughter from someplace far.

“I was hoping you were some bitch,” echoed No-Lee. “Ain’t easy for a guy like to me to get any gash out here. When I’m lucky some stupid cunt will happen on me. It’s good. It don’t happen much, but when it does, oh, is it so good.”

Phillip stood wavering, felt blood beating out of his head, and fell back on his ass.

He couldn’t see No-Lee or the kid, but discerned Jared’s frightened sobs, the twist of a plastic cap against glass. He listened as No-Lee swallowed hard twice, twisted the cap back on. Heard the whoosh of something tumbling through the musty cave air and shattering near the kid’s noise. No-Lee laughed, gagged from the effort. Phillip rose and rushed into the black toward the sound; arms bent ninety at the elbow, hands curled to grasp what he could of No-Lee. When his hands met the man’s chest he gripped and drove his shirt collar to his neck. The two grappled, staggered in the darkness until No-Lee began to vomit and threw his body into Phillip’s, and they fell hard against the wall and ground. An object was knocked over and others crashed out of it near them. From what Phillip could feel with his hands and body, No-Lee was on his side, back against Phillip’s knees. He skimmed his right hand across the dirt, found what felt like a screwdriver. His left hand found the hair on the back of No-Lee’s head, gripped it tight. He rolled himself until he felt that he was on top of No-Lee’s back and brought the screwdriver in his hand to the head in his other quickly, with force. The body beneath him bucked. Phillip struck his left hand on his second stabbing attempt, deeply, and his grip on No-Lee’s hair went slack. So he hugged his head, shook it like he did when Jared was a small child and would ask to be picked up by Phillip to be swung back and forth so that his legs looked like a pendulum. He felt a pop, No-Lee’s body go limp. He collapsed, took his gashed hand in his shirt, and tried to focus on the dimming light of the cave entrance.

§

Phillip never carried a gun before working in Phoenix; had only plinked cans off dirt mounds with small caliber rifles out on the rez with his cousins. The day he decided to carry, a short Guatemalan man had been hired to remove the stucco and chicken-wire siding for an addition. Racial slurs and death threats were being slung at the man because he hadn’t completed the task before Phillip and his boss had shown up to remove the electrical wiring and outlets before the framing could be redone. He remembered the man’s panicked expression and watery eyes, the erratic swing of his sledgehammer, and pleas in Spanish, which Phillip couldn’t understand. The other contractors stood by in an arc, showed each other their handguns and crossed the man with the barrel ends. It would be a temporary thing for Phillip, carrying a handgun. Once he realized he was outnumbered and viewed as no better than the immigrant workers, the other contractors and tradesmen directing their attacks at him, he decided to sell the handgun to a cousin for a couple hundred less than what he paid for it. But the anger and humiliation remained, festered in him, made him judgmental and prone to hate anyone paler than he was. He often dreamed of shooting the racists, the far right-wingers, torching whatever ignorant, upper class project they were working on, and letting everyone and everything burn to ash.

The kid wasn’t crying anymore when he shook Phillip awake, shined the flashlight in his eyes.

“Are you cool? Are you cool?” he repeated until Phillip told him that he was.

“I want to go home,” he said. “We need to go home.”

Phillip sat up and held the kid, told him, ok.

Outside the cave a breeze rustled the pine needles and a far away dog barked once. Phillip felt nauseous and weak, the sensation of the air on his skin made him aware of the heat he felt flaring within him. He wanted to call Benita, have her come get him and the kid. She wouldn’t, he knew, even if he told her the truth. She was driven, career oriented. And, anyway, what good was there thinking about it, he’d smashed his phone yesterday. He felt lost, without purpose. He needed a solution, needed one given to him.

He thought of the body in the cave and his fucking tools. He needed his tools. He told the kid to wait, climbed back into the cave, and gathered his scattered tools; left the screwdriver plunged into No-Lee’s cheek where it was, and hefted the tool bucket and drill bag outside to the base where Jared waited. He smoothed the kid’s hair, told him to stay put, to keep his bats safe and the tools safe. The kid nodded, removed the bats from his pocket, and held them. Phillip, as if driven by instinct, headed toward the pipeline road, some sixty feet through the ponderosas, to a burn pile at the road edge. Something needed to be done about No-Lee’s hateful body, it’d be found sooner or later. Phillip estimated a half an hour to forty-five minutes, if he hustled and didn’t fuck up, in order to remove enough logs to cover No-Lee’s body back in the cave before the forest gave way to complete darkness. He would burn the motherfucker. Char any evidence of him or the kid ever being there. After, he and the kid would walk beneath the night, find a pay phone, if pay phones still existed, and call Benita, beg a ride back to the motel. She’d give in; she would, for him or the kid, it didn’t matter.

As Phillip finished building a pyre over No-Lee’s body, having stuffed the gaps with dry twigs and pine needles, the kid climbed quietly into the cave, sat next to where Phillip knelt, peeled off one of his Bible bats, and set it in an open space between the logs. Phillip began to hiccup and sob, the kid hugged his bruised ribs, and he winced.

The kid said, “We’ll leave them. The bats will protect us.”

Phillip took Jared’s dry and calloused hand, smoothed his hair, and began placing the bats in cracks along the perimeter of the pile. While the kid watched, Phillip ignited the kindling on the far side of the pyre. As it took flame and illuminated the already blackened walls of the cave the two noticed how the smoke wafted up through a natural chimney in the rock. As the bats burned their curled bodies drifted upward until the ash and char of them filled the interior. When the whole of pyre began to burn and the smoke was too much they exited, retrieved Phillip’s tools. When they came upon the far side of the service road they turned around, saw nothing of fire or smoke in the darkness.

Phillip’s tongue fat and course in his mouth. He asked the kid if he was thirsty. He was. But both were without water.

—Bojan Louis

.

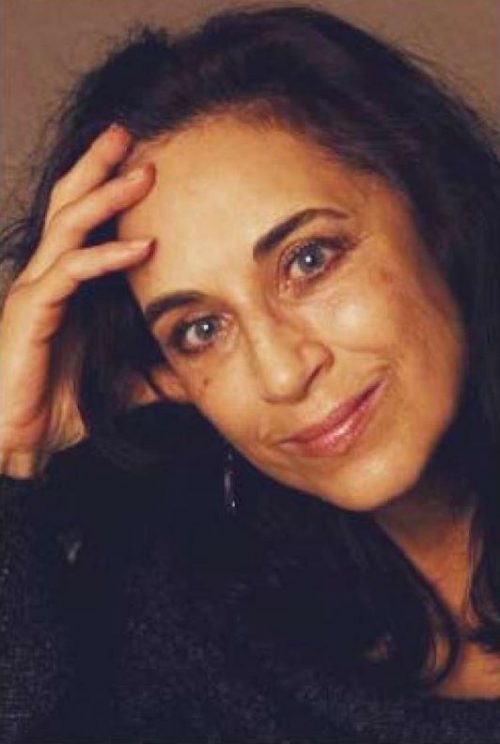

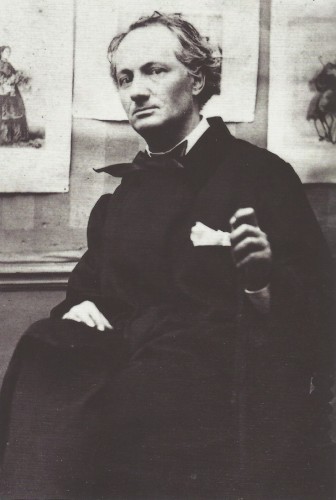

BOJAN LOUIS is a member of the Navajo Nation — Naakai Dine’é; Ashiihí; Ta’neezahnii; Bilgáana. He is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist who earns his ends and writing time by working as an electrician, construction worker, and a Full Time English Instructor at Arizona State University, Downtown Campus. He has been a resident at The MacDowell Colony.

Bojan Louis reading.

Bojan Louis reading.