x

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

— W. B. Yeats

x

x

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Perennial Relevance of “The Second Coming”

PART ONE

The Poem as Response and Anticipation

I. Vexed to Nightmare: The Financial Crisis; the Iraq War; the Rise of ISIS

II. A Vast Image: From Political Genesis to Archetypal Symbolism

PART TWO

Things Fall Apart, Contemporary Crises, 2003-2016

III. Mere Anarchy: Polarization at Home; the Challenges of ISIS and Syrian Immigration

IV. Things Fall Apart: The American and European Political Center Threatened

V. What Rough Beast?: Can (Should) the American Center Hold?

x

x

INTRODUCTION

In his 2016 foreword to the 20th anniversary edition of Infinite Jest, novelist Tom Bissell asks how it is that, two decades after its publication and almost eight years after its author’s suicide, David Foster Wallace’s complex and groundbreaking fiction, though “very much a novel of its time,…still feels so transcendentally, electrically alive?” Wallace himself, as Bissell notes, “understood the paradox of attempting to write fiction that spoke to posterity and a contemporary audience with equal force.” In a critical essay written while he was at work on Infinite Jest, Wallace referred to the “oracular foresight” of writers such as Don DeLillo, whose best novels address their contemporary audience like “a shouting desert prophet while laying out for posterity the coldly amused analysis of some long-dead professor emeritus.” But in the case of those lacking DeLillo’s observational powers, Wallace continued, the “deployment” of, say, contemporary pop-culture “compromises fiction’s seriousness by dating it out of the Platonic Always where it ought to reside.” This observation demonstrates the usual disconnect between Wallace’s lucid critical prose and the enigmatic, multi-layered, funhouse of his fiction. For ought is not is. As Bissell observes, Infinite Jest “rarely seems as though it resides within this Platonic Always, which Wallace rejected in any event.”

Infinite Jest, as its Shakespearean title confirms, is the work of a modern Yorick, a man acutely aware of the contemporary world, especially of the play-element in culture. And yet it is “infinite,” a novel transcendent both in its linguistic exuberance (language being Wallace’s only religion) and in terms of its ambition to express “everything about everything,” even if we are left, 20 years later, still unable to “agree [as] to what this novel means, or what exactly it was trying to say.”

Unlike Wallace, W. B. Yeats did believe in the “Platonic Always”: in that “Translunar Paradise” to which he had been initiated by his studies in the occult and by his later immersion in the Enneads of the Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus. And yet Yeats could, in the same poem (“The Tower,” III) in which he evokes Translunar Paradise, “mock Plotinus’ thought/ And cry in Plato’s teeth.” For the antithetical tension that generated the power of Yeats’s poetry required allegiance as well to the things of this world. Even as he yearned for his heart to be consumed in spiritual fire and gathered “into the artifice of eternity,” he remained “caught in that sensual music,” the very fuel that fed the transcendent flame. These antitheses (cited here from “Sailing to Byzantium”) play out in all those dialectical poems leading up to and away from the central “A Dialogue of Self and Soul” (1927).

In the case of Yeats’s apocalyptic poem “The Second Coming,” written eight years earlier, the “Platonic Always” is present in the poem’s archetypal symbolism: that of a bestial image rising up in the desert. The vision is at once concrete and sublimely vague: timeless, universal, transcendent. Its genesis, however, was thick with particulars. In the process of revision, Yeats deleted (aside from “Bethlehem”) all specific references; but examination of the poem’s drafts reveals that Yeats’s symbolism and apocalyptic prophecy were rooted in his response to contemporary events. In registering details of the moment in time in which he was writing, the immediate aftermath of the First World War, the drafts reveal a poet looking back, into earlier history, and ahead, to our own time, with what David Foster Wallace called “oracular foresight,” and birthing a beast that, a century later, “still feels…transcendently, electrically alive.”

Written almost a century ago, “The Second Coming” has emerged as the prophetic text of our time, uncannily and permanently “relevant.” The best-known poem by the major poet of the twentieth century, it has become something of a requiem for that century, now carried over into the first decades of the twenty-first. That “The Second Coming” is the most frequently-quoted of all modern poems testifies to its remarkable applicability to any and all crises—not only to the Communist Revolution to which Yeats was initially responding when he wrote the poem in 1919, and to the rise of Nazism, which, almost twenty years later, prompted Yeats to quote his own poem; but to the domestic and international crises we ourselves face in 2016, a crucial election year.

A decade ago, “The Second Coming” was often cited in connection with the Iraq War. The 2007 Brookings Institute report on Iraq was titled “Things Fall Apart”; the following year, Representative Jim McDermott called his House speech demanding a strategic plan for Iraq “The Center Cannot Hold.” These days, the disintegrating “center” evokes the polarization of American politics, or the European economic and migration crises, while Yeats’s slouching “beast,” its “hour come round at last,” portends current eruptions in the Middle East, especially the specter of ISIS rising up in the desert and its exportation of terror within and beyond the region. In addition to substantial ISIS-claimed or ISIS-inspired attacks in Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Turkey, Tunisia, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Lebanon, European jihadists inspired by ISIS have launched large-scale attacks in France and Belgium. At the moment I am writing, March 28, 2016, there are threats of further, and imminent, attacks on European targets. As noted at the end of Chapter I, ISIS jihadists have announced that Paris and Brussels are “just the beginning of your nightmare,” and that networks already positioned in Europe are ready to unleash “a wave of bloodshed.” Are “Mere anarchy” and Yeats’s “blood-dimmed tide” about to be “loosed”? And the fearful prospect of radioactive materials in the hands of radical jihadists is now no longer a nightmare but an approaching certainty.

At home, as the survivors of an increasingly sordid and embarrassing primary campaign, the two remaining principal contenders for the Republican presidential nomination out-bellow each other, each boasting, based on zero experience in foreign or military affairs, that he and he alone is the man needed to utterly defeat and destroy ISIS. Listening to simplistic Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, one is reminded of Pauline Kael’s devastating synopsis of John Wayne’s 1955 anti-Communist propaganda movie Blood Alley: “Duke takes on Red China—no contest.” One way or the other, a rough beast is slouching to the Republican convention in Cleveland.

Such Yeatsian allusions have, of course, become commonplace. In accounting for the extraordinary power and perennial relevance of “The Second Coming,” I will illustrate its near-ubiquity and show how Yeats’s revisions of his original (historically-specific) manuscripts universalized the final poem, making it, oracle-like, applicable to all crises, our own included.

↑ return to Contents

x

PART ONE: THE POEM AS RESPONSE AND ANTICIPATION

I. Vexed to Nightmare: The Financial Crisis; the Iraq War; the Rise of ISIS

The genesis of “The Second Coming” is to be located in Yeats’s troubled response to contemporary history, specifically, the European political and economic crises attending the immediate aftermath of the First World War. As I noted in an essay published four years ago in Numéro Cinq, the genesis of my own thoughts on the poem’s timelessness, as an ode for all seasons, was my observation—nearing the tenth anniversary of 9/11—of the remarkable frequency with which “The Second Coming” was being applied—in magazines, newspapers, and blogs—to almost every contemporary crisis or division, foreign and domestic. Centers weren’t holding, conviction was lacking, passionate intensity defined the worst, and rough beasts seemed to be slouching in every direction. It was an old story.

Yeats’s poem in general, and its ominous yet expectant final line in particular, provided, back in 1968, the title for Joan Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” and the iconic collection of the same title. The essay describes an outer and inner de-centering: the ’60s druggy counterculture and the author’s own disintegration as a result of her immersion in the ethos initiated by Haight-Ashbury. The collection as a whole dramatizes the breakdown of order and civility when rough beasts slouch to Los Angeles and New York City. That line continues to inspire allusions. While some found comic relief in Slouching Towards Kalamazoo (the ’60s novel by Peter and Derek de Vries), that judgmental judge, conservative legal scholar Robert H. Bork, titled his grim 2003 projection of an America in cultural and moral decline Slouching Towards Gomorrah. The great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, echoing Yeats’s poem (its first four lines appear as the epigraph), titled his 1958 elegy over the breakdown of Igbo culture Things Fall Apart. In our own contemporary Culture Wars, things continue to fall apart, with communal decency ruptured, on both sides, by political ideology.

Surveying the decline in the quality and civility of specifically conservative discourse, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, himself a conservative, alluded to Yeats’s poem in observing: “It’s a climate in which the best often seem to lack a platform commensurate to their gifts, while the passionate intensity of the worst finds a wide and growing audience.” Rush Limbaugh, who repeatedly moralizes, though with none of Judge Bork’s civility, comes to mind. Notable among Limbaugh’s many pontificating violations of taste and decency was his public branding of a Georgetown law student (an advocate for women’s health issues seeking inclusion of contraception in her college’s insurance coverage) as a “slut” and “prostitute.” That was in 2012, three years before Donald Trump, out-Rushing Limbaugh, found his wide and growing audience.

That famous line made even more famous by Achebe—“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”—has also been aptly applied to the European debt crisis, and its threat to the world economy. In 1919, when he wrote the poem, Yeats was looking out at a postwar Europe torn apart by crippled economies and various national revolutions. Though today we have a “European Union,” it is, economically and demographically, gravely imperiled. Complete financial collapse has been averted by cheap loans from the European Central Bank, and the actions of German Chancellor Angela Merkel (Time Magazine’s 2015 “Person of the Year”). But failure to resolve the underlying problem of the inefficient economic policies of the most indebted nations (Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal) means that we may still face the prospect of what some prominent economists were envisaging—to cite the blood-red cover and banner headline of the August 22, 2011 issue of Time—as nothing less than “THE DECLINE AND FALL OF EUROPE (AND MAYBE THE WEST).”

The cover article itself, titled “The End of Europe,” following in the line of Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart’s 2009 history of sovereign debt, This Time is Different, noted that Europe was not experiencing a typical, correctable recession or even facing “a double-dip Great Recession.” Rather, wrote Rana Foroohar, “the West is going through something more profound: a second [post-1929] Great Contraction of growth,” with investors “suddenly wary that the European center is not going to hold.” Doubling down on that allusion to Yeats, Foroohar began her lead article in Time’s October 10 “special issue” on the economy: “If there is a poem for this moment, it is surely W. B. Yeats’s dark classic ‘The Second Coming’.” She compared what the poet faced in 1919—“the darkness and uncertainty of Europe in the aftermath of a horrific war”—with the current situation. After quoting the poem’s opening movement, and connecting the “centre cannot hold” with the “shrinking” of “the middle class,” Forohoor observed of the poem as a whole, “It’s hard to imagine a more eloquent description of our own bearish age.” Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, saw, even after emergency help, “dark storm clouds looming on the horizon.” The resistance to the austerity pushed by Merkel and the stubborn lack of growth had led to violence in the streets and to the emergence of extremist, fringe parties. Coupled with Muslim immigration and the rise of Islamic extremism, that trend has since continued and intensified: in France, Poland, even in Germany, with the emergence of revanchist and authoritarian parties. Politically as well as economically, it would seem, “the center cannot hold.”

§

Shifting from Europe to the Greater Middle East and beyond, the crises have also intensified, with responses to them participating, rhetorically, in the same pattern: the compulsion to return in times of turmoil to the resonant images of “The Second Coming.” Over the past three years, the poem has been repeatedly quoted in regard to the increasing instability of the international order. Though not the first to consider Yeats’s lines uniquely relevant to their own time, we have a better claim than most. The poem’s opening movement, posted on the website Sapere Aude!, was singled out as the “best description” we have of “the dismal state the world is in right now.” Stephen M. Walt, Professor of International Relations at Harvard, responded to the dangerous “crumbling” of the old “international order” by quoting the whole of “The Second Coming,” a poem that “seems uncannily relevant whenever we enter a turbulent period of global politics.” He concluded “A Little Doom and Gloom” (his sweeping survey of crises in Europe, the Middle East, Iran, and Asia) on a note of foreboding: “I hope I’m wrong, but I think I hear Yeats’s ‘rough beast’ slouching our way.”

Walt’s concerns resonate, and Rogoff and Reinhart may have been right; perhaps “this time” (for, as of March 2016, the European economic crisis is hardly resolved) is “different.” Or it may be that such projections as those sensationalized by that blood-dimmed Time cover were alarmist hyperbole—as charged by one sanguine respondent to the Time issue, who thought “our shifting economies” more likely to be “birth pangs of a new day.” Perhaps; indeed, Yeats’s eternal gyre can be read optimistically, though the birth pangs of his annunciatory rough beast suggest otherwise. When we consider the rise of ISIS and the metastasizing international threat presented by jihadist terrorism, along with Europe’s current immigration crisis, we may conclude that there may be even more terrifying doomsday scenarios in the future. Either way, Yeats’s “The Second Coming” will remain in attendance, ready to supply apt metaphors embodying our sense of an ending: the dying of one age, with another, yet unknown, “to be born.”

This talismanic poem’s projection of cyclical and violent rebirth in the form of a sphinx-like beast rising in the desert eerily foreshadows today’s Middle East, most dramatically, the rise of ISIS out of the wreckage of Syria and Iraq. The once hopeful Arab Spring has long since turned autumnal. Caught up in the region’s cross-current of sectarian, ethnic, and tribal tensions, overwhelmed by military elites and by long-suppressed but well-organized Islamists, the young rebels who actually initiated the Arab Awakening quickly became yesterday’s news. Revolutions devour their own children. History “Whirls out new right and wrong,/ Whirls in the old instead,” to quote Yeats’s “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” a poem originally titled “The Things That Come Again.” As two Middle-East experts, Hussein Agha and Robert Malley, accurately predicted as early as September 2011: whatever the outcome of this struggle, “victory by the original protesters is almost certainly foreclosed.” And so it has turned out. Optimistic anticipations of beneficial change were shattered by what Agha and Malley called, perhaps echoing the Yeatsian widening gyre, “centrifugal forces” (“The Arab Counterrevolution”). Many in the chaotic Middle East are now, as various Islamic sects vie for power, and ISIS galvanizes jihadists, wondering what comes next—or, in Yeats’s stark image of expectation-reversal, what rough beast is slouching their way.

The long-sustained hostility has also intensified between Israel and the Palestinians, with the elusive two-state solution further away than it was when the UN partitioned Palestine 2/3rds of a century ago. That embittered stalemate is epitomized in the title of a recent book, Side by Side: Parallel Narratives of Israel-Palestine. In lieu of advancing any proposals to resolve the issue, the book offers, on facing pages, differing perspectives on the same events. The “sheer reciprocal incomprehension” in these parallel narratives, with “two sides locked in…a dialogue of the deaf,” reminded British journalist Geoffrey Wheatcroft of a famous phrase of Yeats (for once, not from “The Second Coming,” but from “Remorse for Intemperate Speech,” a poem written a dozen years later): “Great hatred, little room.”

Like many lines from “The Second Coming,” this phrase, too, applies throughout much of the Greater Middle East. In Syria, Bashar al-Assad, militarily propped up by Vladimir Putin, continues to barrel-bomb his own people, while we puzzle over how, now that one plan to arm the Syrian “moderate” opposition has ignominiously failed, we might prevent further carnage. In Afghanistan, what began as a justified attack on the Taliban sponsoring al Qaeda now seems a futile counter-insurgency: a struggle hampered by our putative “ally” in the region. Playing both sides in its own self-interest, Pakistan covertly supports the resurgent Taliban it originally created and funds extremist madrassas (now over 1,300) intended to displace Afghan state schools, where secular subjects are taught as well as religion. And Pakistan is itself an unstable nation, its nuclear arsenal partially dispersed and therefore vulnerable to seizure by its own Islamist radicals.

And then there is the nuclear game-playing of a truly paranoid regime. North Korea is already in possession of several nuclear weapons, and its erratic dictator, 33-year-old Kim Jong-un, has become increasingly provocative. North Korea’s nuclear bomb test in January was quickly followed by a rocket-launch, part of a project whose goal is to eventually mount a nuclear warhead on an intercontinental missile. The rocket was launched not only in violation of several UN Security Council resolutions, but even in defiance of the Hermit Kingdom’s powerful neighbor, China, the only nation thought to have the leverage to restrain its unpredictable ally. Apparently not; Kim Jong-un is spinning out of control, threatening, in March 2016, to aim nuclear missiles at Seoul and Washington. A propaganda video released the same month depicted a submarine-launched ballistic missile visiting nuclear devastation on the US capital.

There is a double threat involving Iran: the danger of that theocracy violating the recent accord by surreptitiously working to develop a nuclear weapon, and of the predictable and unpredictable ramifications of an Israeli and/or US preemptive strike. Should our policy be to prevent, to contain, or to attempt to destroy? This issue, politicized in this election year, has become as polarized as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And yet, unless the nuclear agreement works, unless reason on both sides prevails and the center holds, we may be careening into yet another, and potentially even more profoundly destabilizing, war in the Middle East.

In Iraq, we have ended our large-scale military presence after a war we should never have started. But in toppling Saddam Hussein, we rid Iraq of a brutal and megalomaniacal dictator whose tyrannical reign had at least one positive aspect: his repression of militant Islamists. As a result we have left behind not only an economically ravished country (35% of those fortunate enough to have survived Operation Iraqi Freedom live in abject poverty), but one divided along predictably sectarian lines. The discrimination against the ousted Sunnis, not yet redressed by Haider al-Abadi, who succeeded Nouri al-Maliki as Prime Minister in 2014, not only affects every aspect of life, but alienates (since they have little incentive to protect the Shiite government in Baghdad) the very Sunni fighters needed to resist ISIS.

The negative consequences of our misguided disbanding of Saddam’s Sunni army after its defeat in 2003 were compounded by our decision to back Maliki over secular Shiite Ayad Allawi, whose party won the March 2010 parliamentary elections, but fell two seats short of a majority. Maliki, pressured by Shiite Iran, broke his pledge to integrate the government and instead institutionalized the repression of the Sunnis. Obama was urged to cease supporting Maliki by, among others, Ali Khedery, who served as special assistant to five US ambassadors to Iraq and as a senior advisor to three CentCom commanders. Khedery concluded a 2014 opinion piece:

By looking the other way and unconditionally supporting and arming Maliki, President Obama has only lengthened and expanded the conflict that President Bush unwisely initiated. Iraq is now a failed state, and as countries across the Middle East fracture along ethno-sectarian lines, America is likely to emerge as one of the biggest losers of the new Sunni-Shiite war, with allies collapsing and radicals plotting another 9/11. (Washington Post, 3 July 2014)

Shortly after we initiated the Iraq War, a Syrian businessman, Raja Sidawi, a friend of Washington columnist and writer David Ignatius, offered a prescient observation. Ignatius cited it, somewhat skeptically, in his July 1, 2003 Washington Post column, “The Toll on American Innocence.” A dozen years later, in October, 2015, he reprised it; and its second coming—in a cover-piece in The Atlantic, “How ISIS Spread in the Middle East”—was far more somber. What Raja Sidawi told his American friend in June 2003 was this: “You are stuck. You have become a country of the Middle East. America will never change Iraq, but Iraq will change America.” Given his cultural and practical knowledge of the region, Sidawi’s remark may not quite match the oracular clairvoyance so many of us have found in Yeats’s “The Second Coming.” But it will do. We stormed into Iraq with “shock and awe”; and with hubris, a mixture of political duplicity and the American confidence of Innocents Abroad—“innocence” indistinguishable from ignorance. We changed; the region didn’t. The result: a variation on the old Sunni-Shiite war, “with allies collapsing and radicals plotting another 9/11.”

§

Principal among those plotting radicals, their brutal implementation of an apocalyptic theology flourishing in the implosion of Syria and Iraq, is of course the Islamic State: ISIL, or Da’esh, best known as ISIS. Confronted by the spectacle of ISIS, commentators from Left and Right, including experts on Islamist terrorism, turned in 2015 to Yeats’s “The Second Coming.” In a Huffington Post piece titled “ISIL: The Second Coming,” composer Mohammed Fairouz, whose setting of Yeats’s poem premiered in New York City on March 10, applied his epigraph, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity,” to President Obama’s failure to confront barbarous ISIS early on. A June 2015 posting on a West Coast socialist website, titled “Iraq: ‘Things Fall Apart’,” cited the opening three lines of the poem, noting that Yeats “might have written today, and nowhere is this more true than in Iraq.” In a blog posted in August, a former liberal turned Neo-conservative announced, “Read this, and think of ISIS.” The “this” was the full text of “The Second Coming.” The poem had been haunting her, she reported, since 9/11, and “these days it seems more than ever that the rough beast is on the march.”

Between these two, in a July Wall Street Journal essay, “A Poet’s Apocalyptic Vision,” David Lehman, himself a poet, described “The Second Coming,” extrapolating from the moral anarchy of 1919, as a fearful pre-vision of our present anarchy. “If our age is apocalyptic in mood—and rife with doomsday scenarios, nuclear nightmares, religious fanatics, and suicidal terrorists—there may be no more chilling statement of our condition than” this poem, in which Yeats envisages no Christian “second coming,” but “a monstrosity, a ‘rough beast’ threatening violence commensurate with the human capacity for bloodletting.” The accompanying color illustration— a slouching leonine creature with light beaming from mouth and eyes—attempts to visually capture that “gaze blank and pitiless as the sun.” But the image, in this case, is a counter-example to the cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words, or even (if they are Yeats’s) seven words.

Photo by Yao Xiao

Photo by Yao Xiao

After sketching its historical, psychological, and occult contexts, Lehman focuses on the text, celebrating the poem’s “metrical music,” “unexpected adjectives,” and such “oddly gripping” verbs as “slouches,” as well as Yeats’s “epigrammatic ability,” best exemplified in the last two lines of the opening stanza: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity.” The aphorism, says Lehman, retains its authority as both “observation” and “warning.” We may, he suggests (yielding to the irresistible impulse to specify politically), “think of the absence of backbone with which certain right-minded individuals met the threats of National Socialism in the 1930s and of Islamist terrorism in the new century.” He concludes by recommending that we read the poem aloud to appreciate its “power as oratory,” and then ask ourselves which most “unsettles” us: “the monster slouching towards Bethlehem or the sad truth that the best of us don’t want to get involved, while the worst know no restraint in their pursuit of power?”

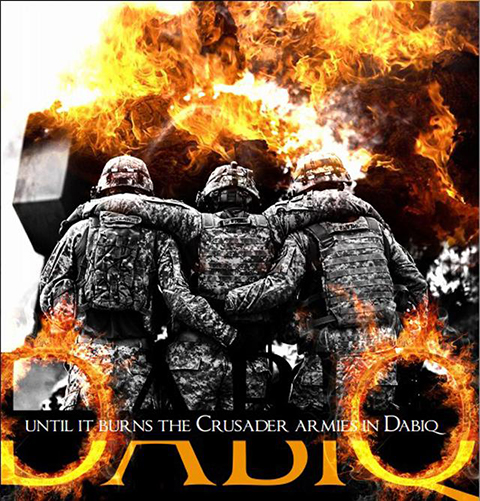

Lehman’s question is valid, despite his being unaware that Yeats, interpreting Marxism-Leninism as a second coming of the Jacobin Terror of the French Revolution, initially identified the “worst” with the Bolsheviks, perpetrators of such revolutionary crimes as the slaughter of the Russian royal family; while the putative “best” were vacillating European moderates and liberals who had failed to respond to, much less resist, revolutionary brutality. In its initial drafts, “The Second Coming” reflected Yeats’s response to the violence in Russia in light of the violence in France a dozen decades earlier. But in its final version, the poem also looks, almost clairvoyantly, ahead to the future. And even French and Russian revolutionary brutality can seem tame in comparison with the theologically inspired and politically intimidating barbarism of ISIS, with its mass rape and enslavement, beheadings and crucifixions, and its growing capacity to inspire and ignite terror attacks well beyond the borders of its Caliphate in Syria and Iraq. ISIS is also seeking radioactive materials. As in the past, “The Second Coming” is at hand to supply metaphors. In the final pages of ISIS: The State of Terror, two noted experts on Islamist jihadism, Jessica Stern and J. M. Berger, quote “The Second Coming,” and then conclude:

It is hard to imagine a terrible avatar of passionate intensity more purified than ISIS. More than even al Qaeda, the first terror of the twenty-first century, ISIS exists as an outlet for the worst—the most base and horrific impulses of humanity, dressed in fanatic pretexts of religiosity that have been gutted of all nuance and complexity. And yet, if we lay claim to the role of “best,” then Yeats condemns us as well, and rightly so. It is difficult to detect a trace of conviction in the world’s attitude toward the Syrian civil war and the events that followed in Iraq….

The double point made by Stern and Berger epitomizes their theme as well as the current crisis, marked by the bloodlust and passionate intensity of the “worst,” and the lack of conviction the civilized world, the “best,” has thus far displayed in fully engaging this religiously inspired death cult. Reviewing this book, and two others on ISIS, Iraq specialist Steve Negus remarks that “only one quotes Yeats’s ‘The Second Coming,’ but the others must have been tempted” (New York Times Book Review, April 1, 2015). Negus was writing before the publication of the latest book-length study, counterterrorist expert Malcolm Nance’s Defeating ISIS: Who They Are, How They Fight, What They Believe (2016). He was also writing five months prior to the publication of perhaps the best of the bunch: The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State, by William McCants. His deep knowledge of ISIS’s political strategy and apocalyptic theology reflects McCants’s immersion in primary Arabic sources. His good-news, bad-news conclusion is that ISIS will be defeated, but that its example will inspire future jihadists. McCants does not cite “The Second Coming.” However, given his richly informed apocalyptic emphasis, it seems safe to imagine that he, too, “must have been tempted.”

In the month I am writing, March 2016, US commandos killed the Finance Minister of ISIS, and, as a result of coalition bombing and Iraqi army advances, ISIS is losing some ground in Syria and Iraq. But even as its Caliphate contracts, ISIS is expanding—geographically into Libya and elsewhere, and exporting terror throughout the Middle East and Africa, and into the heart of an under-prepared Europe. Last November’s coordinated attacks in Paris, which took 130 lives, were replicated by members of the same Molenbeek-based Belgian cell in Brussels on March 22, when two brothers and a third suicide bomber slaughtered 31 and wounded almost 300. Hundreds of alienated European Muslims, radicalized and militarily trained by ISIS in Syria, are now back in Europe, organized in operational cadres. In a video released on March 25, two Belgian ISIS fighters warn that “This is just the beginning of your nightmare.” Promising more “dark days” ahead for all who would oppose them, the terrorists in command of ISIS have threatened that jihadists already positioned in Europe are prepared to unleash a “wave of bloodshed.” Once again, “Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,/ The blood-dimmed tide is loosed.…”

↑ return to Contents

II. A Vast Image: From Political Genesis to Archetypal Symbolism

In accord with the mystery of the Sublime, Yeats’s sphinx-like beast slouching blank-eyed toward Bethlehem is a horror capable of many interpretations but limited to none, and, therefore, all the more terrifying. For that very reason, as I’ve just illustrated, “The Second Coming” is perennially relevant. Almost a century after the poem first appeared, pundits in books and essays, newspapers and magazines, routinely draw upon Yeats’s evocation of cultural disintegration and imminent violence, and lines from the poem (the whole poem, in Joni Mitchell’s 1991 riff) riddle popular culture, as we can see by consulting Nick Tabor’s recent compendium of dozens of pop-culture allusions, itself titled “No Slouch.”[1] More gravely, as part of our common crisis-vocabulary, we intone that “things fall apart”; that “the centre cannot hold”; that “the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity”; that “the ceremony of innocence is drowned”; that we confront forces “blank and pitiless as the sun”; that one era, symbolized by a “widening gyre,” is ending and another imminent, signaled by the loosing of a “blood-dimmed tide” of “mere anarchy,” dreadfully attended by a “rough beast” slouching towards Bethlehem to be born. How has the poem achieved this Bartlett’s-Familiar status?

An Endless Source

x

In addition to those already mentioned in the text, there are many titular allusions to “The Second Coming.” Canadian poet Linda Stitt considered calling her 2003 collection Lacking All Conviction, but chose instead another phrase for her title: Passionate Intensity, from the line of “The Second Coming” that immediately follows. Describing a very different kind of disintegration than that presented by Judge Bork in Slouching Towards Gomorrah, another law professor, Elyn R. Saks, called her 2007 account of a lifelong struggle with schizophrenia The Center Cannot Hold.

x

Detective novels, crime fiction, and pop culture in general have drawn liberally on the language of “The Second Coming.” The second of Ronnie Airth’s Inspector John Madden novels is The Blood-Dimmed Tide (2007). H. R. Knight has Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle tracking down a demonic monster in Victorian London in his 2005 horror novel, What Rough Beast. Robert B. Parker called the tenth volume in his popular Spenser series The Widening Gyre. I refer in the first endnote to Kevin Smith’s Batman series appearing under that general title.

x

Science fiction writers seem particularly addicted to language from “The Second Coming.” Among the episodes of Andromeda, the 2000-2005 Canadian-American sci-fi TV series, were two titled “The Widening Gyre” and “Its Hour Come Round at Last.” But the prize for multiple allusions goes to a project that originally appeared as a six-part e-book in 2006 (marking the 40th anniversary of the original Star Trek series). An omnibus edition, Star Trek: Mere Anarchy, was published in 2009. This “Complete Six-Part Saga” takes from Yeats more than its main title (also borrowed by Woody Allen for his 2007 collection of comedy pieces). All six of the individual novellas in Mere Anarchy (each by a different author) derive their titles from “The Second Coming”: Things Fall Apart, The Center Cannot Hold, Shadow of the Indignant, The Darkness Drops Again, The Blood-Dimmed Tide, and Its Hour Come Round.

A friend, Bill Nack, biographer of the great racehorse Secretariat and an informed reader of Yeats’s poetry, remarked of “The Second Coming” in a letter: “So many lines and images are written indelibly, chipped in stone on that wailing-wall we call the 20th, now the 21st century.” The poem is a mine of incisive and quotable phrases, from the opening movement’s bullet-point declarations (fusing metaphor and abstraction, chaos and order) to that final momentous question. The presentation is cinematic, with the “vast image” looming gradually, and dramatically, into focus: a mere “shape,” then “lion body,” then “head of a man,” then a zooming in on the creature’s “gaze,” followed by a panning movement back out, since that gaze is “blank and pitiless as the sun.” In addition to the tensile strength of its unforgettable verbs (loosed, troubles, reel, vexed, slouches), the poem’s extraordinary power is attributable to its sources in the occult and the unconscious, its Egyptian and mythological reverberations, and, above all, its alteration of the Bible (Daniel, the gospels, Revelation), culminating in the shock value of the subversion of the Christian interpretation of the “second coming.” “The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out” than the poet envisages, not the return of Christ, but the advent of a sinister rough beast. Apparently moribund for two millennia, it is now, ominously and sexually, “moving its slow thighs,” while “all about it/ Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.” Indignant because those circling scavengers had mistakenly thought the immobile creature mere carrion; but the beast, imperceptibly stirred into antithetical life by the rocking of Jesus’ cradle two thousand years earlier, is alive. Now, initiating a new cycle, it slouches, provocatively and precociously, towards that infant’s birthplace in order itself “to be born.”

But the poem’s universal relevance, its adaptability, is, above all, testimony to the success of Yeats’s method in revising the original manuscripts. Written in January 1919, first printed in The Dial in 1920, and collected the following year in Michael Robartes and the Dancer, “The Second Coming” had its sociopolitical roots, as the poet’s widow confirmed in the 1960s, in Yeats’s troubled response to the political situation in Europe in 1917-19. And the drafts of the poem, some of the pages preserved by his wife, reveal that Yeats’s apprehensions about the socialist revolutions in Germany, Italy, and, above all, Russia, during and immediately after World War I, were associated, as we’ve seen, with his reading of the Romantic poets and of Edmund Burke, and their responses to the French Revolution: what Shelley called “the master theme of the epoch in which we live.”

As earlier noted, Yeats initially identified the “worst” with the Bolsheviks, perpetrators of such revolutionary crimes as the slaughter of the Russian royal family; while the putative “best” were those who had failed to resist, eventually epitomized, for Yeats, by the British King, George V. As it happens, Kerensky’s Russian Provisional Government had initiated an offer of asylum, promising to send the Tsar and Tsarina and their children to England for safety: an offer rejected by the King (fearful of reaction from the British Labor Party), even though he was Nicholas’s cousin. This cowardice and violation of the family bond, not known to Yeats at the time he wrote “The Second Coming,” surfaced two decades later in “Crazy Jane on the Mountain,” where Yeats’s most famous and least inhibited female persona is revived to bitterly decry the fact that

A King had some beautiful cousins

But where are they gone?

Battered to death in a cellar,

And he stuck to his throne.

Tsar Nicholas II and family, ca. 1914 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Tsar Nicholas II and family, ca. 1914 (via Wikimedia Commons)

But “The Second Coming” resonates far beyond that old atrocity. It looks back from the Bolshevik to the French Revolution, as filtered through Yeats’s reading of Edmund Burke and the Romantic poets.[2]

Yeats’s natural affinities were with his major poetic precursors, those permanent revolutionaries Blake and Shelley. But in his own political response to revolution, Yeats found himself closer to the great Anglo-Irish conservative statesman Burke, the chief intellectual opponent of the French Revolution and chivalric champion of the assaulted Marie Antoinette. He also found himself aligned with a former supporter of the Revolution (“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,/ But to be young was very heaven”): the largely if not completely disenchanted William Wordsworth. At this time, Yeats was reading the French Revolutionary books of Wordsworth’s Prelude as well as Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. His own ambivalent response to catastrophe (horrified and yet strangely exultant), as projected in “The Second Coming,” registers the differing perspectives of Burke and the Romantics on the French Revolution, now refracted through the prism of what Yeats took to be its rebirth in Bolshevism.

An idiosyncratic yet often complex and even profound visionary, Yeats was as much a disciple of Nietzsche as of Blake and Shelley, and an occultist to boot. All of these influences, along with his conservative reverence of Swift, Burke, and of an idealized Anglo-Irish aristocracy, as well as his response to Wordsworth’s Prelude, converge in “The Second Coming,” as in its close relatives, “A Prayer for My Daughter” and the sequence “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.” All three reflect, along with the Great War and the Bolshevik Revolution, the beginning of the War of Independence in Ireland. And they all recapture Burke’s elegy over the fall of Marie Antoinette, and his premonition of “the glory of Europe…extinguished forever,” of “all…to be changed.” The sequence’s recurrent “nightmares” and the drowning of “the ceremony of innocence” in “The Second Coming” echo Burke’s “massacre of innocents” (with the palace at Versailles “left swimming in blood”) and Wordsworth’s “ghastly visions” of “tyranny, and implements of death,/ And innocent victims,” in passages of The Prelude dramatizing his reaction to revolutionary massacre. Such echoes confirm Yeats’s juxtaposition of the excesses of the French Revolution with the postwar turmoil in which he was writing in 1919.

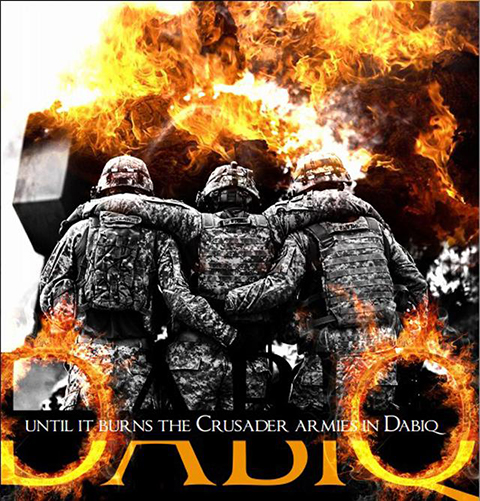

Deciphering Yeats’s handwriting and interpreting his associative connections, we can trace in the drafts of “The Second Coming” his linking of Burke’s lamentation over the assaulted Marie Antoinette with the spectacle of the Russian royal family, including the Tsarina Alexandra, “battered to death in a cellar” (as he would have Crazy Jane later put it). Yeats connects Bolshevik brutality with such French atrocities as the September Massacres and the Jacobin Terror—what, annotating Wordsworth, he characterized as “revolutionary crimes.” In the face of “unjust tribunals,” with admitted royalist “tyranny” replaced by “mob-bred anarchy,” Yeats laments that there’s “no Burke to cry aloud, no Pit[t]”—no one, that is, to “arraign revolution,” as Burke had in the Reflections and in later speeches and William Pitt in ministerial policy. In further noting that “the [G]ermans have now to Russia come,” Yeats seems to combine the 1917 military invasion of Russian territories with the decisive German role in spiriting Lenin, and thus Marxian Communism, into Russia. As a result: “There every day some innocent has died” in revolutionary purges epitomized by the Bolsheviks’ July 1918 slaughter of the Tsar, the Romanov children, and the Tsarina Alexandra: “this Marie Antoinette,” who “has more brutally died.” The crucial point is that, as he continued to revise, Yeats stripped “The Second Coming” of all these particularized references. What prompted him to do this? The drafts themselves offer intriguing clues.

Pages from drafts of “The Second Coming”

Pages from drafts of “The Second Coming”

Deciphering Yeats’s handwriting

x

Despite the conjectures necessitated by the rapid scribbling of a man whose handwriting was maddeningly difficult to begin with, most of the specifics and the gist of what Yeats means are clear in this early draft (page 1., image above):

x

Ever further h[aw]k flies outward

from the falconer’s hand. Scarcely

is armed tyranny fallen when

when this mob bred anarchy

takes its place. For this

Marie Antoinette has

more brutally died and no

Burke [has shook his] has an[swered]

with his voice, no pit [Pitt]

arraigns revolution. Surely the second

birth comes near—

x

……….intellectual gyre is thesis to

The/ gyres grow wider and more wide]

The falcon cannot hear the falconer

The germans have now to Russia come

There every day some innocent has died

The [ ? ] comes to [?fawn]…[?murder]

x

In other drafts (all Box 3, Folder 39, W. B. Yeats Collection, SUNY, Stony Brook), Yeats confirms his regret that there’s no Burke or Pitt to arraign Bolshevik crimes as they had French Revolutionary terrorism: “—no stroke upon the clock/ But ceremonious innocence is drowned/ While the mob fawns upon the murderer/ And there’s no Burke…nor Pitt….”; and, again, “there’s no Burke to cry aloud no Pit[t].” Astutely analyzing the drafts in 2001, Simona Vannini had no doubt about the coupling of French and Russian atrocities. But, resisting the “scholarly consensus” (she refers to Donald Torchiana, Jon Stallworthy, and myself), she doubts, based on the drafts alone, that Yeats intended an “explicit correspondence between the murder of the French and the Russian royal families.” But one does not live by the drafts alone.

x

Finally, as slowly but surely as the rough beast itself, the poem as we know it begins to emerge (pages 2.-4., image above).

§

In the most dramatic of the visions induced in Yeats during some 1890 symbolic-card experiments with MacGregor Mathers (the head of Yeats’s occult Order, the Golden Dawn), the poet suddenly saw, as he records in an unpublished memoir, “a gigantic Negro raising up his head and shoulders among great stones”—a vision transmogrified, in the published Autobiographies, into “a desert and a Black Titan.” Even in this dramatic instance, Yeats continues, “sight came slowly, there was not that sudden miracle as if the darkness had been cut with a knife.” In the drafts of “The Second Coming,” groping for figurative language to introduce the mysterious moment immediately preceding the vision of the vast image rising up out of “sands of the desert” and “out of Spiritus Mundi,” Yeats first wrote: “Before the dark was cut as with a knife.” Whether examining the finished poem or the drafts, we are surely justified in locating one of the principal origins of the rough beast in Yeats’s occult experiments with MacGregor Mathers.

We may also have, in the cautionary example of Mathers himself, a key to Yeats’s abandonment, in the course of revision, of the historical figures and events specified in the drafts. Yeats found his occult friend’s apocalyptic imagination, “brooding upon war,” impressive when it remained “vague in outline.” It was when Mathers “attempted to make it definite,” that “nations and individuals seemed to change into the arbitrary symbols of his desires and fears.” Yeats was aware of the tendency of literalists and cranks to apply the obscure symbols of Revelation to the world-historical crisis of their own particular moment in time. This is what Mathers was in the habit of doing and what Yeats had initially done, as evidenced by the drafts of “The Second Coming.” Of course, it was what the Apocalyptist himself had done in producing a text that was less an inspired prophecy than a coded account of events happening at the time he was writing. But there was one clear prophecy. John insists, following Paul and Jesus himself, that the promised second coming was imminent. Implicit throughout Revelation, that prophecy is explicit and particularly resonant at the end, where John puts the premature parousia in Christ’s own mouth, “Surely, I am coming soon” (echoed by Yeats: “Surely the Second Coming is at hand…”), and concludes by intensifying the urgency in his own voice: “Come, Lord Jesus!” (22:20)

Less interested in correlating specific events with Revelation or in predicting the future than he was in artistically mining Revelation as a rich source of resonant symbolism, Yeats was particularly fascinated by sublime aspects of the apocalyptic Beast: simultaneously menacing, exciting, destructive, and potentially renovative. (In depicting the first coming of Christ, he had referred, in the turbulently sublime final line of his visionary poem “The Magi,” to “The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.”) Above all, Yeats, as visionary, would have had no desire, by binding his prophecy to particular events, to make himself ridiculous—as had many biblical scholars, or MacGregor Mathers. That would be to succumb to what Alfred North Whitehead would later call (in one of Yeats’s favorite books, Science and the Modern World) “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.”

St. Jerome, aware of the many strained, historically specific misreadings preceding his translation of the Bible, was content to revise previous commentaries on the Book of Revelation rather than venture one of his own. As he observed in a letter, “Revelation has as many mysteries as it does words.” The same might be said of the final version of “The Second Coming,” which retains Yeats’s own “desires and fears” without limiting those generalized (“abstract”) emotions to the specific (“concrete”) historical events that originally provoked them. That the beast slouches, in the single vestige of specificity, towards Bethlehem makes the creature a type of the Antichrist. But Yeats was hardly a conventional Christian pitting sectarian goodness against Satanic and bestial evil. In fact, while the final poem and title refer to Christ’s parousia, the original drafts repeatedly refer, not to the “second coming,” but to the “second birth,” echoing Wordsworth’s “nightmare” premonition in The Prelude that the “lamentable crimes” of the September Massacres were not the end of revolutionary violence in France, but a precursor of the far worse Terror to come: “The fear gone by/ Pressed on me like a fear to come…”

For the spent hurricane the air provides

As fierce a successor; the tide retreats

But to return out of its hiding-place

In the great deep; all things have second birth. (Prelude 10:71-93)

Wordsworth’s image of a malevolent and returning tidal sea may remind us not only of the loosing of “the blood-dimmed tide” in Yeats’s poem of “second birth,” but of another powerful, and no less apocalyptic, prophesy of “coming” destruction. In Robert Frost’s 1926 couplet-sonnet, “Once By the Pacific,” the water is “shattered,” and “Great waves looked over others coming in,/ And thought of doing something to the shore/ That water never did to land before.” This is an unprecedented rather than repeated act of destruction, but its premeditated “thought” makes Frost’s ocean even worse than Yeats’s “murderous innocence of the sea” (in “A Prayer for My Daughter,” where revolutionary violence takes the form of “sea-wind…/ Bred on the Atlantic”). Though Frost’s shore “was lucky in being backed by cliff,/ The cliff in being backed by continent,” the sea seems backed by God himself, whose creative fiat in Genesis, “Let there be light,” is soon to be superseded by his apocalyptic extinction of light:

It looked as if a night of dark intent

Was coming, and not only a night, an age.

Someone had better be prepared for rage.

There would be more than ocean-water broken

Before God’s last Put out the Light was spoken.[3]

In that final line, Frost moves from Genesis (1.3) to the Book of Revelation (21:1). In reversing Christian expectation (in Matthew 24 and Revelation), the poet of “The Second Coming” echoes the whole of the Prelude passage, which ends with Wordsworth returning to Paris, scene of the worst atrocities of the September Massacres, to find the place “unfit for the repose of night,/ Defenceless as a wood where tigers roam.”[4] Yeats’s “strong enchanter,” Nietzsche, author of The Antichrist, invoked a Dionysian and eternally recurrent “savage cruel beast”: an eruptive force incapable of being “mortified” by what he called, in Beyond Good and Evil, these “more humane ages.” Unsurprisingly, since Yeats believed that “Nietzsche completes Blake, and has the same roots,” and that “Nietzsche’s thought flows always, though with an even more violent current, in the bed Blake’s thought has worn,” Nietzsche’s beast (first trotted out in Yeats’s 1903 play Where There is Nothing) later resonated in his archetypal mind with Blake’s Tyger and his half-bestial Nebuchadnezzar, slouching on all fours (as in Daniel 4:31-33) on Plate 24 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

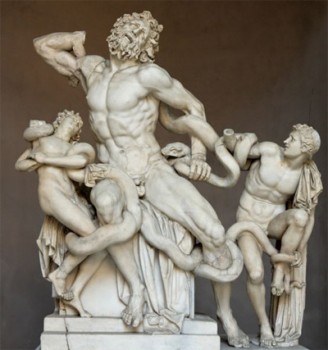

Nebuchadnezzar by William Blake (via Wikimedia Commons)

Nebuchadnezzar by William Blake (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Rough Beast

x

The vast image or animated sphinx “out of Spiritus Mundi” has many “sources.” It can be traced back to the most dramatic of the mental images induced in Yeats during the symbolic-card experiments he conducted in 1890 with MacGregor Mathers, the dominant figure in the occult Order of the Golden Dawn. In his most memorable vision, Yeats saw a “Black Titan” rising up ominously from the desert sands. Other components are drawn from Shelley’s stony pharaoh Ozymandias (his wrecked statue almost lost among the “lone and level sands”) as well as from his Demogorgon (in Prometheus Unbound): a nightmare denizen, along with the “rough beast” of “The Second Coming,” of the mysterious “Thirteenth Cone” in Yeats’s occult book, A Vision.

x

Around 1902, Yeats “began to imagine” a brazen winged beast “afterwards described in my poem ‘The Second Coming’.” In that same year, in his uncanonical play Where There is Nothing, he envisaged a laughing, destructive beast resembling the eternally recurrent “savage cruel beast” of Nietzsche: a Dionysian, libidinal, eruptive force incapable of being “mortified” by what Yeats’s “strong enchanter” called (in Beyond Good and Evil) these “more humane ages.”

x

In perhaps the most momentous of his imaginative fusions, Yeats believed that “Nietzsche completes Blake and has the same roots,” and that Nietzschean thought “flows always, though with an even more violent current, in the bed Blake’s thought has worn.” The rough beast of “The Second Coming” can be seen as a fusion of Nietzsche’s savage cruel beast with (along with the dragons of Revelation and of comparative mythology) aspects of Blake’s Urizen, his Tyger, and his bestial Nebuchadnezzar, crawling on all fours at the conclusion of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

x

In the 1795 color print reproduced here, Blake returned to the image he had engraved on the final plate of The Marriage. In Daniel 4:33, the Babylonian king, cursed and “driven from men,” ate “the grass as oxen”; his hair “grew like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws.” Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar, his mind darkened, stares, unseeing, directly at us. Though his “gaze” is as “blank” as that of Yeats’s “rough beast,” Blake’s king is more terrified than terrifying. But his bestiality and slouching posture is likely to have contributed to the composite beast of “The Second Coming.”

All precursors of the “rough beast.” But Yeats’s response to French revolutionary violence, and its rebirth, was at least as powerfully influenced by the bestial imagery and conservative politics of Edmund Burke. For conservative Yeats, the September Massacres and French Reign of Terror foreshadowed the emergence in Bolshevik Russia of that “Marxian criterion of values” he described in a letter of April 1919 as “in this age the spearhead of materialism and leading to inevitable murder”: the same inevitability Burke had early and uncannily prophesied in 1790. In terms of imagery, attitude, and actual verbal details, “The Second Coming” would be a very different poem if it had not had precisely this twin historical genesis. Finally, however, the poem, in its final, published text, is not “about” either the French or the Russian Revolution.

Nor is it about the National Socialist revolution. Many readers have taken it that way, citing a 1936 letter in which Yeats, refusing to politicize the Nobel Prize by recommending a German dissident writer, also condemned Nazism, quoting the most Burkean line in the poem as evidence that he was not “callous”: “every nerve trembles with horror at what is happening in Europe, ‘the ceremony of innocence is drowned’.” While Hitler, with the help of Goebbels, read himself positively into the Book of Revelation, as a secular Aryan Messiah and initiator of the thousand-year Third Reich, Yeats, though a man of the Right, saw the Führer as a type of the apocalyptic beast. In applying to Nazism and the threat of a second world war an image he drew from Burke and applied to the First World War and the threat of Jacobinism reborn as Marxist-Leninist Communism, Yeats was being neither hypocritical nor intentionally misleading. Indeed, he was participating in a tradition of allusion that goes on to this day. And justifiably. For if “The Second Coming” were “about” any one of these historical cataclysms, it could hardly accommodate, as it does, all of them.

§

No less a figure than Goethe has said that to be fully understood, works of art must, to some extent, “be caught in their genesis.” The manuscripts of “The Second Coming” serve a legitimate purpose in revealing the original historical counterparts of what became a universalized prophecy of an unleashing upon the world of anarchy and blood-drenched violence. The speaker has had an apocalyptic vision, a “lifting of the veil” (the Greek meaning of Apokalypsis) and the disclosure of something hidden from the rest of us. But when “the darkness drops again” over the manuscripts, as it should, we are left with what really matters—the public text of the poem, freed of the umbilical cord attaching it to its genesis, and thus limiting its evocative power.

If, in studying any poem, particularly one responding to contemporary events, we were to focus unduly on generative intention, and on the immediate context of its creation, the poem would inevitably dwindle in meaning and impact as that particular moment receded. Yeats’s realization of this explains his deletion, in revising “The Second Coming,” of specific historical details. In Waiting for Godot, Yeats’s fellow Irishman and fellow Nobel Prize winner, Samuel Beckett, achieved symbolic resonance by avoiding all overt reference to the historical-political matrix of the play: the German Occupation and French Resistance. Similarly, by cancelling allusions to the Irish situation and all specific references to past and contemporary revolutions, to Burke, Marie Antoinette, Pitt, Germany, and Russia, Yeats liberated his poem from those localized events destined to be assimilated like so many grains of sand in the desert of time. As an anti-Marxist, Yeats would have enjoyed the effect, since it is Marxist critics above all who have been disturbed by the autonomy of works of art, by their capacity to outlive their particular hour—what Geoffrey Hartmann has memorably called art’s “aristocratic resistance to the tooth of time.”

Insistent that the power of his images derived in part from their roots, Yeats declared in “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” one of his late retrospective poems: “Those masterful images because complete/ Grew in pure mind, but out of what began?” As we’ve seen, “The Second Coming” arose out of two sources, particular and universal. The specific events that provided its initial stimulus helped to shape the final poem. But Yeats, who was, like Carl Jung, fascinated not only by the occult but by alchemy, knew what he was doing when he transmuted the base metals of his historical minute particulars into the poetic gold of universally resonant archetypes. The archetypal symbols he received, or evoked, especially that mysterious and bestial “vast image” taking form “somewhere in sands of the desert,” came, he asserts, “out of Spiritus Mundi”: out of the World Soul that Jung—who reported strange beasts troubling the dreams of his own patients during the First World War—called the Collective Unconscious. That storehouse of archetypes causes universal symbols to arise in individual minds. But if the symbols in “The Second Coming” reflect Yeats’s own immersion in what he called the “Great Memory,” it is also, since each mind is linked to it, our Unconscious as well. In the dialectic of Yeats’s symbolic poems, myth is personal and experience is mythologized. In a similar reciprocity, allusions to “The Second Coming” register individual responses to current crises, contemporary forebodings which, simultaneously, resonate with eternally recurrent archetypes transformed by a great poet into “masterful images.”

“The Second Coming” obviously and dramatically transcends the minutiae of its origins. But it is one thing to simply be general and abstract, quite another to universalize after having delved deeply into, and worked through, materials that are concrete and specific. The method of Yeats—who always insisted that “mythology” be “rooted in the earth,” that we must delve “down, as it were, into some fibrous darkness”—falls into this second category. Influenced, as was Joyce, by the cyclical philosophy of Giambattista Vico, Yeats agreed with Vico that “Metaphysics abstracts the mind from the senses; the poetic faculty must submerge the whole mind in the senses. Metaphysics soars up to the universal; the poetic faculty must plunge deep into particulars” (Scienza Nuova, 1725). Yeats has it both ways in “The Second Coming.” The specific details of the poem’s political genesis have been buried; but the poet’s rooting of his fears and cryptic prophecy in contemporary history—significant soil enriched by the conflicting responses of Burke and Wordsworth, Blake and Shelley, to the great upheaval of their era—surely contributed to the unique power of a disturbing poem whose universalized vision of violent transformation haunted the rest of the twentieth century, and shows every sign of haunting ours. Without that rooting in Viconian and Blakean “particulars,” idiosyncratic theories and his obsession with what Joyce mockingly called Yeats’s “gygantogyres” could easily have produced oracular bombast that would be truly “callous” and shapelessly rather than sublimely vague.

What we have instead is a poem in which Yeats has it several ways at once. The seer casts a cold eye on the whirling of gyres beyond our control, yet seems, at least in part, excited by the rebirth of cyclical energy. But the note of boredom-relieving anticipation detectable in “its hour come round at last” is offset, not only by the elegiac Burkean music of the opening movement, but by the poem’s deepest tonality. For the real surprise, trumping the Nietzschean irony that this “second coming” will take a very different “shape” than that expected by naïve, optimistic Christians, is that Yeats’s own expectation will be exposed as a pipe dream. We must trust the tale and not the teller. For the poem itself, less aloofly visionary than human, suggests that the antithetical era being ushered in will not assume the hopeful form of the Nietzschean-aristocratic civilization welcomed (“Why should we resist?”) in Yeats’s long note to the poem. Instead, the newborn age is likely to take the chaotic shape prefigured by its brutal engendering. With that deeper insight, that peripeteia or sudden plot-change and readjustment of apocalyptic expectation, both the theoretician and the cold-eyed oracle in Yeats yield to the poet and man whose vision of the beast truly “troubles my sight.” This troubled vision is also rooted in apocalyptic literature. Yeats is doubtless recalling the response of the prophet Daniel (two hundred years before an echoing John of Patmos) to the final and most “terrifying and dreadful” of the “four great beasts” he sees in a dream: “my spirit was troubled within me, and the vision in my head terrified me….I was dismayed by the vision and did not understand it” (Daniel 7:19-20, 8:15-27; cf. Revelation 13:7).

Yeats’s dramatic plot-change, foreshadowed in the poem’s drafts, is reflected in his final punctuation. Violating the grammatical logic of its own peroration, “The Second Coming” ends in a question, leaving us with an open, apprehensive, awestruck glimpse of imminent apocalypse, or transformation, or the loosing of a blood-dimmed tide of terror that may constitute (to again quote Shelley on the French Revolution) “the master-theme” of the post-9/11 “epoch in which we live.” Yeats was even more honest when, in the drafts of the poem, he explicitly acknowledged that whatever gnosis was involved was not his, but the beast’s: “And now at last knowing its hour come round/ It has set out for Bethlehem to be born.” In the poem as published, we are left with human uncertainty rather than prophetic certitude. The syntactical and vatic momentum that follows “but now I know…” is retained, and yet the poet ends, as Daniel had, with a cryptic, troubling vision he “did not understand,” and therefore with a genuine question: the mark of interrogation that always, according to the unknown Greek author of the great treatise On the Sublime, attends that mystery.

Peering into the dark forward and abysm of time, their sight “troubled,” readers of Yeats’s poem are easily persuaded that something ominous is afoot. But we are left wondering which of our own current crises might emerge as no less transformative than the events Yeats was responding to in the manuscript-drafts of “The Second Coming,” specifically his connection of 1919 with the bloodshed following 1789. As those drafts reveal, Yeats was paralleling the two most momentous events in the history of the modern Western world: the French Revolution, and its blood-dimmed aftermath, with the First World War and its various sequelae. The consequences of the Great War include the global influenza pandemic that swept away at least 10 million more people than the 37 million fighters and civilians lost in the war itself, as well as the slicing of the modern Middle East out of the rotting carcass of the Ottoman Empire. Before the 1921 Cairo Conference, which created, ex nihilo, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Syria, John Maynard Keynes warned the man who had presided over this division, British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill: “If you cut up the map of the Middle East with a pair of scissors you will still be fighting wars there in a hundred years’ time.” Five years from that centennial, Keynes seems no less prophetic, and rather more specific, than the poet who envisaged anarchic disintegration and a beast rising from “somewhere in sands of the desert.”

Though excised by the poet, and partially erased from our collective memory by a historical flood bringing even greater calamities, those World War I-related events sowed the seeds of much that followed. Even Yeats’s stress, in the manuscripts, on the execution of the French queen and its repetition in the massacre of the Russian royal family, were not idiosyncratic choices. Whatever one thinks of Yeats’s politics or of the hapless Romanov dynasty, Yeats was not simply—in Tom Paine’s trenchant critique of Burke’s tear-stained apostrophe to Marie Antoinette—“pitying the plumage while forgetting the dying bird.” Alexandra (“this Marie Antoinette” who has “more brutally died”) was battered and shot to death with her husband and children in the “House of Special Purpose” in Ekaterinburg. Though there was no signed order, the ultimate decision was Lenin’s. Those murders marked a pivotal moment when—in the summation of historian Richard Pipes in his magisterial The Russian Revolution—history made a turn toward genocide, when human beings were placed on a list of expendables and the world entered “an entirely new moral realm.”

Yeats sensed this seismic change and registered it in the drafts from which “The Second Coming” evolved—though he saw it not as “an entirely new” moral phenomenon but as a “second birth” of revolutionary massacre. The execution of the Russian royal family—the barbarous slaughter, in particular, of the children, shot, clubbed, and stabbed to death by drunken incompetents—was Yeats’s contemporary example of the loosing of a blood-dimmed tide and slaughter of the innocents that, for him, hearkened back to the French Reign of Terror and, for us, as readers of “The Second Coming,” prefigures all the horrors of the twentieth century and beyond: war, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, genocide, famine, economic chaos, ecological degradation, melting ice shelves and rising sea levels, and political anarchy—in the form, in our own country, of an ideological and special-interest polarization so intense that the center can no longer hold.

Yeats’s prophetic poem—as open to interpretation as the Beasts and Dragons and Horsemen of the Biblical Apocalypse—envisages, or, rather, can be made to envisage, any and all of these nightmares. Front and center at the moment is ISIS: the apocalyptic cult of fanatics operating out of their medieval Caliphate and able to ignite or at least inspire terror wherever the Internet and the various forms of social media they have mastered can reach. ISIS does not exhaust the legion of threats our own century of stony sleep has vexed to nightmare. Like Yeats, we are left wondering “what rough beast, its hour come round at last, /Slouches towards” us?

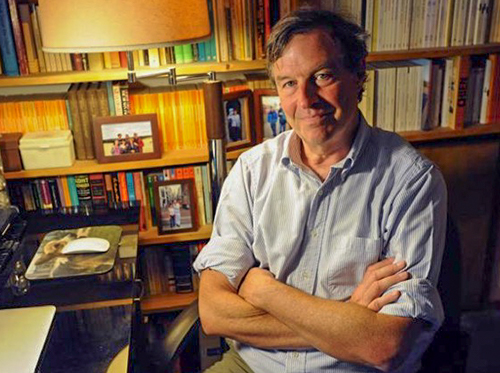

W. B. Yeats, 1932 (photo by Pirie MacDonald)

W. B. Yeats, 1932 (photo by Pirie MacDonald)

In Part Two, we will revisit the turmoil of the Middle East and the rise of ISIS. Though both have deep causal roots, both are the immediate result of our 2003 decision to invade Iraq: a disaster exacerbated by its antithesis: President Obama’s understandable but consequential decisions and then indecisions regarding the Syrian civil war. The US invasion and occupation of Iraq are the roots of the tree from which most of the poison fruit has fallen, but the carnage and chaos in Syria not only expedited the rise of ISIS but produced the current immigration crisis. It is a tragic history.

When various moderate factions first rose up against the Alawite tyranny of Bashar al-Assad, it seemed part of the hopeful Arab Spring. Obama, who had been criticized for his alacrity in abandoning President Mubarak in Egypt, was now criticized for his reluctance to urge the ouster of Assad. After several months of calibrated diplomacy and sanctions, Western policy shifted to regime change. In tandem with French President Nicolas Sarkozy, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and British Prime Minister David Cameron, President Obama announced that, for the good of the Syrian people and before his regime was utterly rejected by them, the time had come for “President Assad to step aside.” The policy became distilled to three fateful words: “Assad must go.”

That was in August, 2011, when perhaps 2,000 had been killed in the conflict. Figures differ, but a consensus estimate is that, in the subsequent five years of civil war, well over 300,000 Syrians and non-Syrian combatants have been killed, while another 70,000 have perished because of lack of water, medicine, and other basic necessities. Assad alone is responsible for the slaughter of 10% of his own people, over 40% of them civilians. In 2013, President Obama, in a decision as fateful as the announcement that Assad must go, drew a red line, threatening to attack Assad if he used chemical weapons against his own people. When the Syrian President crossed that line, twice, Obama, on the verge of ordering airstrikes, reversed himself, for reasons, and with consequences, we’ll revisit. Meanwhile, the slaughter continued. In addition to the deaths, nearly two million people have been wounded in the ongoing conflict, and approximately 120,000 are currently starving and freezing in towns besieged by government or anti-government forces, and subject to bombing—from the air by Assad and (until recently) by his Russian ally, and, on the ground, by the various warring factions, especially ISIS, which recently launched its worst bombing attack of the war, killing at least 130 people.

The continuing horror in Syria has also created a wider humanitarian and political crisis. Millions of refugees have inundated not only the region but a Europe already buckling under the burden of debt and demography, and giving rise to right-wing anti-immigrant movements that are now threatening centrist governments. The primaries leading up to our own 2016 presidential election—driven by populism on the Left and, most dramatically, on the Right—exposed a fragile political center that, here as in Europe, may not hold. Thrilling some, dismaying most, a nativist rough beast, Donald Trump, is slouching towards Cleveland to become the presumptive Republican nominee, or to hurl the convention into anarchy.

↑ return to Contents

x

PART TWO: THINGS FALL APART, CONTEMPORARY CRISES, 2003-2016

III. Mere Anarchy: Polarization at Home; the Challenges of ISIS and Syrian Immigration

Its evocation of imminent yet mysterious catastrophe has made “The Second Coming” the swan song of our time. As the 20th century’s preeminent visionary poet, Yeats, alert to the dangers of hubristic Enlightenment faith in reason and the utopian myth of collective moral progress, was also telepathically attuned to the paradoxically related loosing of the tides of irrational fanaticism. Religion obviously plays a role in a cyclical poem in which the Christian era’s twenty centuries of “stony sleep” are said to have been “vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle”: a nightmare that takes the shape of an apocalyptic beast returning to Bethlehem to be born. But in the twenty-first century, there is an even more terrifying twist on the visionary “nightmares” that rode upon Yeats’s sleep in “The Second Coming” and “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.” For today, the forces of irrationalism threatening civilization are quintessentially theological and not only committed to terrorism, but, potentially, armed with the most nightmarish, even apocalyptic, weapons.

In part a reaction to Western colonialism and more recent US intervention, militant Islam has deep theological roots in the “sword-passages” of the Quran. Though we have no choice but to confront the threat of jihadist terrorism, our “global war on terror” is both quixotic and often counter-productive. In the Bush-Cheney administration, Neo-conservative hubris joined with the evangelical notion that it is our messianic mission to extend to all cultures, however little we may understand the ethno-sectarian complexities, what President Bush invoked as “the Almighty’s gift of universal freedom.” The result was the disastrous decision to invade Iraq, worsened when “liberation” became occupation. Worst of all, in the case of such stateless actors as al Qaeda and affiliated jihadists, and now, in the case of ISIS, our global war tends to generate more terrorists than we can kill. We face a metastasizing religious fanaticism impervious to traditional forms of rational or military deterrence and driven by the mad conviction that any and all forms of terror against the infidel West are part of a holy war carried out to avenge past injustices, all under the auspices of their approving God.

President Obama’s anti-terrorist policy, militant but limited, and only partially effective, will doubtless be intensified, whether Hillary Clinton or a Republican is the next President. If the latter, the principal competing visions may once again become apocalyptic, with each side embarked on a sacred mission to eradicate perceived evil. Along with religious-right hawks, we have militants ranging from Rapture-ready End-Timers to apocalyptic Christian Zionists to unreconstructed theoconservatives still clinging to a version of Bush’s Bible-based foreign policy. Despite Ted Cruz’s hyperbolic pledge to make the desert sands “glow,” there is a significant difference between the combatants: a distinction made graphic in the recent nuclear threats by apocalypse-hungry ISIS jihadists, whose suicide belts and Kalashnikovs will seem a quaint memory once they have acquired enough radioactive material to build a divinely sanctioned dirty bomb.

And then there is Iran. Its Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khameinei, insists that the endlessly reiterated chant, “Death to America,” is aimed, not at the American people, but at the US government and its “arrogant policies.” There is a danger of that distinction blurring should Khameinei—despite the more “moderate” elements in his government and against the majority wishes of the Iranian people, as reflected in the March 2016 elections—choose to resume Iran’s drive to acquire a nuclear weapon. Iran is already defying UN sanctions by testing missiles, tests not covered in the recent US-Iran strictly nuclear agreement. Any cheating on that nuclear accord would invite, well beyond sanctions, harsh retaliation, probably in the form of a massive preventive airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities—by the US alone, or in concert with Israel. No one knows what geostrategic repercussions might follow.

A greater nightmare scenario involves actual rather than potential nuclear weapons, with more to come. Pakistan is planning to more than double its arsenal of 100 warheads, including tactical (“battlefield”) weapons, which lower the threshold to nuclear war. And Pakistan, which would then be the fifth-largest nuclear power, is a state (to cite the title of Ahmed Rashid’s recent book) “on the brink” of chaos, perhaps in the form of an Islamist coup. Nine years ago, a matured Benazir Bhutto returned to Pakistan, determined to resist such militants. “Extremism” can be contained, she said, “if the moderate middle can be mobilized to stand up against fanaticism.” Just before the general election, she was assassinated. No Pakistani since has mobilized any “moderate middle,” and there is no prospect of any “center” likely to “hold.” Even if there is no full-scale coup, Pakistan’s arsenal—widely dispersed to deter the perceived enemy, India—will become still more vulnerable with the addition of those smaller, easier-to-steal “battlefield” nuclear weapons. They, or larger warheads, could be seized by a now more globally oriented Pakistani Taliban or by a post-bin Laden al Qaeda still inspired by 9/11: in both cases, terrorists clearly willing to use even these ultimate weapons in the name of Allah.