Curious and maze-like story behind this delightful essay about an atypical Mennonite childhood in southern Ontario: Rick Martin lives in Kitchener, Ontario (it used to be Berlin, Ontario, but was renamed after a famous English general—Lord Kitchener—during the First World War). He lives next door to dg’s old friends Dwight and Kathy Storring. Long ago in the Triassic or, maybe, the Cretaceous, Kathy was a reporter at the Peterborough Examiner while Dwight took photos and dg was the sports editor (yes, yes, we all have a secret, sordid past). Kathy showed Numéro Cinq to Rick and Rick got inspired by the NC Childhood series to write his own story. Kathy showed Rick’s essay to dg, and here we are. (Accept this is a peek into the byzantine editorial apparatus behind NC—if you want to get published here, it helps to move next door to the Storrings.)

Rick Martin is a technical documentation and training consultant. He has taught technical and business writing at the University of Waterloo and York University. He has had dozens of technical manuals published and has written numerous essays and poems for his own pleasure and the enjoyment of family and friends.

dg

/

“What is a true story? Is there any such thing?” Margaret Laurence, The Diviners

I was a shy child and bewildered by almost everything around me.

My mother and father were born into horse-and-buggy Mennonite families in Waterloo County, Ontario. My father’s family were regular Old Orders, who eventually moved to the more modern Conference (or “red-brick”) Mennonite church so that my grandfather could have a truck to haul his produce to the Kitchener market. My mother’s family belonged to the more extreme Dave Martin Mennonite sect (founded by her grandfather), and when my grandparents were born again and joined the small Plymouth Brethren congregation in Hawkesville, they were completely shunned by their family and friends.

My father was a long-distance truck driver, so he was often absent. My parents’ first child died in his crib when he was four months old, so there was always a ghost in our lives. When I was 18 months old, my little sister was born several months premature and lived in an incubator at the hospital in Kitchener for months. With no means of transportation to the city and no one else to look after my older brother and me, my mother was stuck at our rented farmhouse near St Clements, unable to care for her fragile new baby.

When I was still quite young, my mother, on the verge of mental collapse, had a spectacular conversion, in which Jesus appeared to her in a vision and assured her she was saved and going to heaven. This experience gave her strength to carry on through the adversities of near blindness from a childhood eye infection, too many kids (there were soon 5 of us), poverty, and a mostly absent husband who, she was convinced, was not saved: Dad drank and smoked and swore, had an explosive temper, and didn’t much like going to church.

When I was 5, my dad was transferred to Sault Ste Marie, 500 miles from family, friends, and any sense of security we had. We lived in a rented farmhouse about 5 miles west of the city for the first year, then bought an unfinished 3-bedroom house in a barely developed subdivision on the eastern fringes of town: gravel roads, no municipal water or sewers, roadside ditches, and no bus service for the first few years. Because my mother couldn’t see well enough to drive a car, we were stuck in the neighbourhood except on the weekends, when Dad was home.

With her fundamentalist mixture of Dave Martin Mennonite and Plymouth Brethren beliefs, fed by radio preachers like Theodore H. Epp, my mother thought that TV, movies, card-playing, and dancing were all worldly, if not sinful. We grew up believing that everyone around us was a heathen, headed for hell, intent on tempting us into lives of sin. We could play with neighbourhood kids, but we understood they were different than us, and we shouldn’t get too close to them (in the summer, my mother held Daily Vacation Bible Schools in our yard, in an effort to convert our friends).

I knew, from the time I was conscious, that I was a sinner, headed for hell unless I accepted Jesus as my saviour. And I knew—from my mother’s and grandparents’ experience—that such a conversion was dramatic, that when you were saved, you knew it. Jesus never appeared to me, despite my nightly pleading, and I was never able to find the assurance that he lived in my heart.

Dad, of course, was a worry. I was pretty sure he wasn’t saved, and I knew he was in constant danger: fellow drivers were periodically killed in spectacular crashes, skewered by steel against some rock-cut on the winding road to Toronto. We prayed on our knees for his safety and his salvation, among other things, every night before bed.

And we believed in the Rapture, that Christ could appear at any moment and sweep true believers up into heaven, leaving the unsaved to a horrible stint with the anti-Christ. This was a concept invented by the founder of the Brethren, John Darby.

In many ways, the east end of Sault Ste Marie was a wonderful place to be a child. Just a block south of our house, on the other side of Chambers Avenue, there was bush all the way to the St Mary’s River, and on the other side of highway 17, a half mile north of us, it was bush pretty much all the way to James Bay.

The neighbourhood was all young families with lots of kids and not a lot of discipline. We ran wild, exploring and building tree-forts. We played baseball in empty lots and kick-the-can and hockey on the streets. At night, there were hide-and-seek games that ranged across the whole block of back yards.

We’d take day-long hikes back into the bush on the other side of the highway, cutting across the Indian Reserve and getting lost in the meanderings of the Root River. We built rafts in the drainage ditches and ponds down towards the river. We rode our bikes down to Belleview Park in the city and 7 miles out to Hiawatha Park to go swimming. In winter, we would hang onto the rear bumpers of cars and slide along behind them until they got going too fast and we rolled off into the snowbanks.

Mom often didn’t have a clue where we were or what we were doing; she just prayed constantly that we’d all get home safe and sound for supper.

Every Sunday, there were three services at Bethel Bible Chapel on North Street: 9:30 Breaking of Bread, 11:00 Family Bible Hour with a sermon for the parents upstairs and Sunday School for the kids in the basement, and 7:00 Gospel Hour. We rarely went to the first service, but almost always to the other two. If Dad was too tired, Mom would arrange for someone else to take the rest of us.

It was at Sunday School, we understood, that we could make real friends: these were Christian people, unlike our neighbours in the east end. So Sundays were the high point of the week. Often I would be invited to a friend’s place for the afternoon, between services. I soon realized that not all Brethren families were like ours. Most of them had much nicer homes and furniture and toys than we did, some of them had TVs, and many of them had a happy, easy-going, fun-loving approach to life. A few of the kids, whose parents had invited me, were selfish and nasty and treated me like dogshit on their shoes.

We’d often have Sunday School friends come home with us, too. Dad was the cook on Sundays, and he usually made a big mid-day meal of roast beef or pork and mashed potatoes and gravy and tossed salad. After dinner, we’d often go for a drive and a hike at Gros Cap or somewhere along the Lake Superior shore. I was always sad when the Sunday evening service was over and we’d pile into the car for the drive home to another week of school and neighbourhood friends.

Mom read stories to us every night before we said our prayers, things like The Five Little Peppers. It seemed our house was full of reading material (especially compared to those of our neighbours): the Bible, of course, but also novels, magazines, and newspapers. Mom was always reading, with her book held close to her nose, and—when he was at home and awake and not fixing something—Dad was often in his easy chair reading the Family Herald or National Geographic or some trucking journal. I can remember starting to learn to read, identifying letters and words, sitting on Dad’s lap while he read the newspaper.

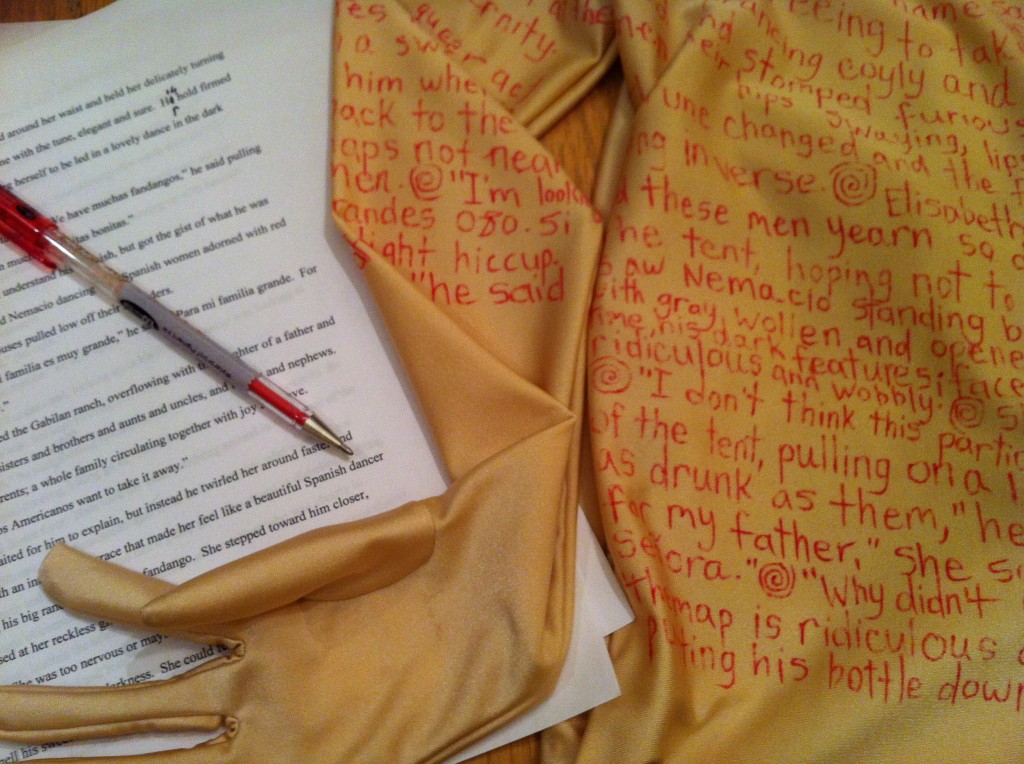

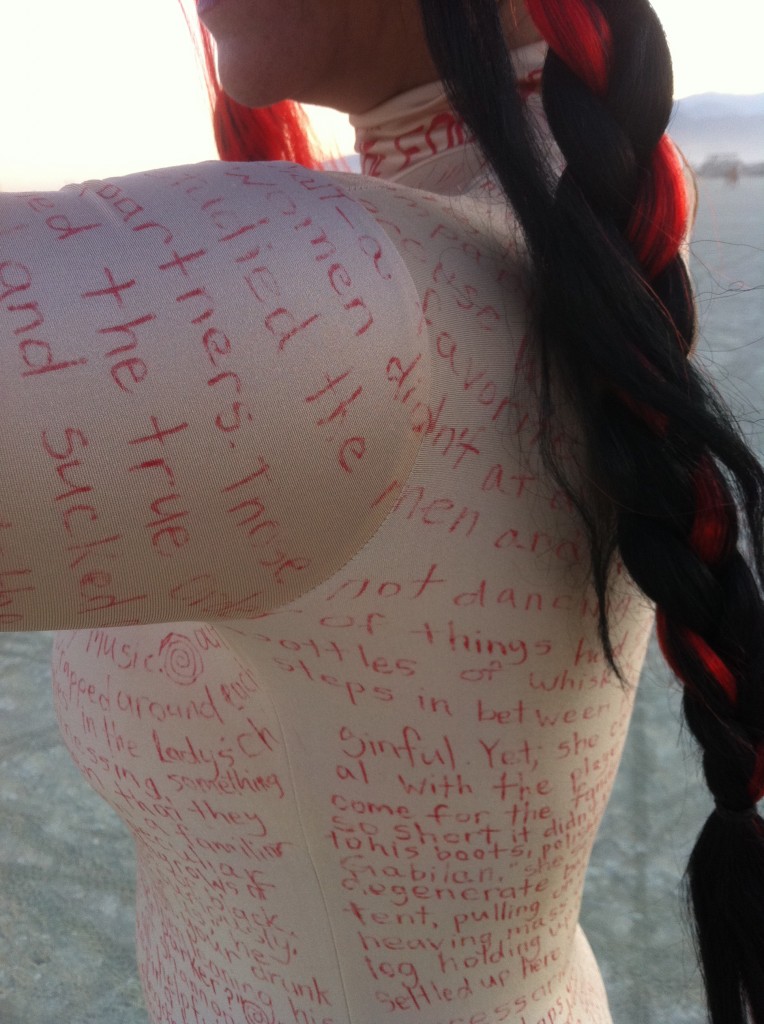

At first, most of our reading material other than newspapers was religious in nature. Every Sunday, we got little pamphlets from Sunday School, and every Christmas our Sunday School teachers gave us story books and, later, novels with blatantly evangelistic aims. But when we got access to school and city libraries, we read the Hardy Boys, Enid Blyton’s several series, the Swallows and Amazons books, and all sorts of stuff: pretty much anything we could get our hands on. Eventually, in high school, I graduated to Steinbeck, Hemingway, Kerouac, and Kesey.

My older brother was always pursuing some hobby—stamp collecting, oil painting, magic, photography—with a passion that was infectious. I’d always end up doing what he did. I sent money off to some mail-order place in BC to get bags of stamps and bought an album to put them in. I got hold of an old Brownie somewhere. I helped my brother develop our film in the little dark room he carved out amongst the boxes in the tiny attic off our bedroom. But somehow, I could never generate the enthusiasm he had for these activities. It was always a borrowed interest, not strong enough to sustain me.

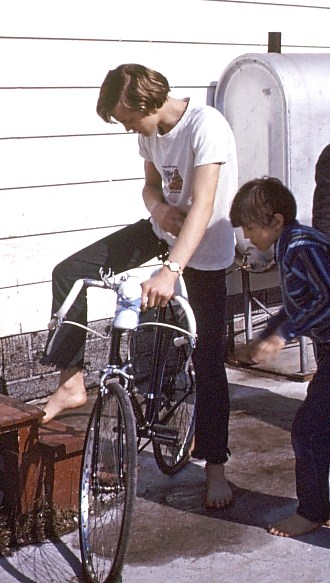

The one thing I did take up more or less on my own was a fascination with bicycles. I collected old frames and wheels in the annual spring clean-up, and from them I’d assemble strange bikes: I remember one that had a 28-inch front wheel and a 20-inch back wheel. About grade 8, I put together one of the first 10-speeds in town from parts I had lying around, parts I scrounged, and parts I bought at my friend George’s father’s hardware store. I would ride all over town, exploring every neighbourhood, and out into the countryside as far as Island Lake and St Joe’s Island.

I was also infatuated with cars and knew the year, make, and model of almost everything on the road by the time I was 5 or 6. Dad subscribed to Mechanics Illustrated, and I’d avidly read Tom McCahill’s car reviews every month. We would go to the annual Auto Show at the Memorial Gardens, and I’d drool over the new models. I remember the first Mustang I ever saw and the first MGB. I thought I’d gone to heaven when my dad’s friend took me for a ride in the ’66 Dodge Charger he bought with insurance money from the truck he’d crashed on highway 69.

Our family was always short of money, usually running up a bill at Jean’s Handy Store for bread and milk between pay-cheques. Among other methods of getting cash, we’d pick wild blueberries in the late summer and sell them door-to-door in the neighbourhood for 10 cents a quart.

When he was still pretty young, maybe 10 or 11, my older brother got a paper route, delivering the Toronto Telegram across the whole East Side, and I was conscripted as his helper. The first night was miserably cold and snowing, and we wandered about through the snow drifts looking for addresses on Boundary Road and Trunk Road, a mile or more from home. We split up to find the last few houses, he in one direction and me in the other, and I never did find the one I was looking for. I arrived home what seemed like hours later, freezing and wet and miserable, feeling a failure.

When I was 12 or so, I landed a Sault Star route, and my dad loaned me the $50 to buy a brand new Super Cycle 3-speed, electric blue, with chrome fenders. I had about 50 customers spread along a 3- or 4- mile route that wound through the neighbourhood and ended up at the Husky Truck Stop down the highway at the very edge of town. For awhile, I had several customers across the tracks on the Rankin Reserve. I cleared about 5 dollars per week.

In the summer, I’d strap the paper bag on the back of the bike and race through the route in just over an hour, but in the winter, it was a long, slow slog in the dark, with the bag biting into my skinny shoulder and my hands freezing. When I got home, everyone else would have already finished supper, and I’d eat alone while Mom washed the dishes and my younger sibs dried them and put them away.

One year—1966, I think—as a bonus for signing up new customers, I won a trip to Toronto with a bunch of other carriers and some crusty old newspaper types as chaperons: it was the first time I’d been away from home with strangers. We stayed at the King Edward Hotel. We saw the Toronto Maple Leafs play the Detroit Red Wings, the first time I’d seen a professional hockey game (no TV, remember). And we went to see the movie Fantastic Voyage. It was the first time I’d ever been in a movie theatre, and my lack of familiarity with the conventions of either film or science fiction rendered the narrative completely unintelligible. The whole weekend was equally surreal and disturbing.

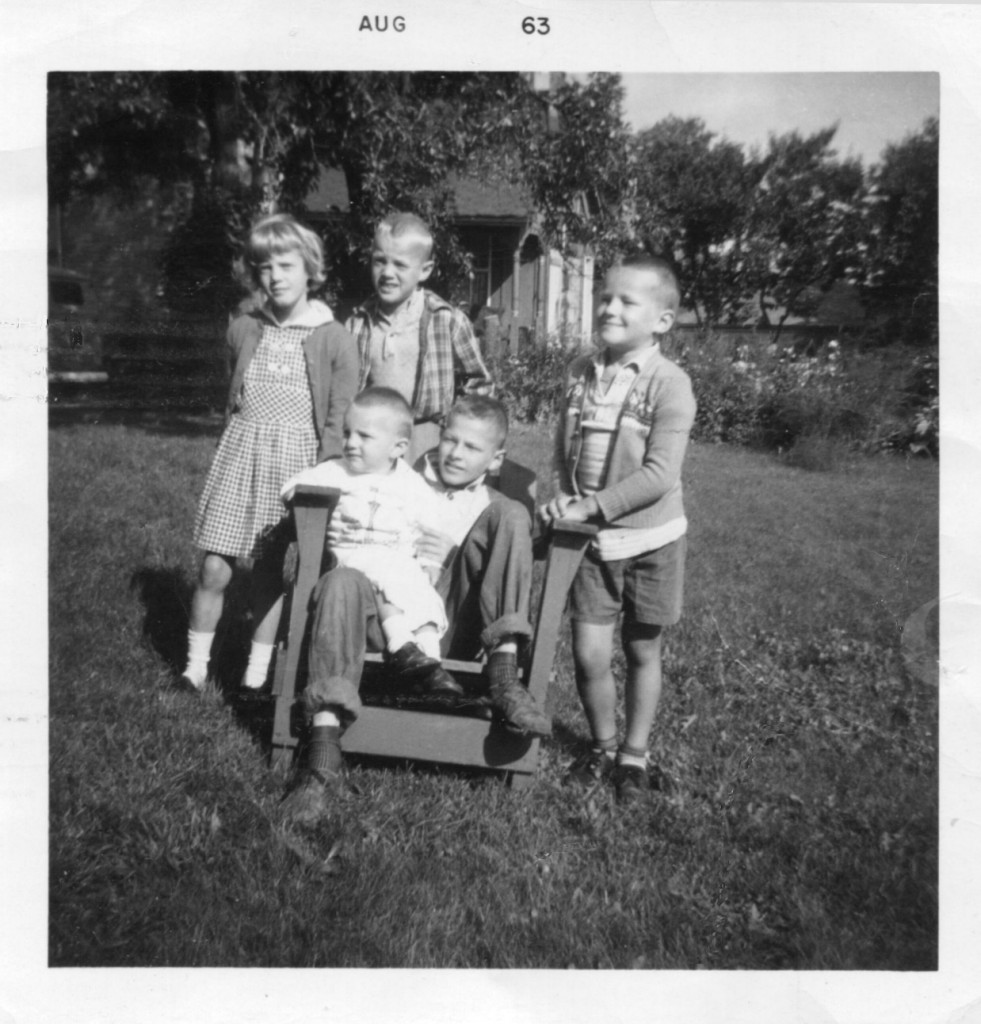

Sunday Afternoon at Grandma’s in Waterloo, 1963.

Sunday Afternoon at Grandma’s in Waterloo, 1963.

Mom always put a very high value on education (she and Dad had only gone as far as grade 8), and I did well in school, usually at the top of my class. But there was really little competition, given the sub-working-class character of our neighbourhood, and there was only one other boy, Roger, who did anywhere near as well as I. The other boys were all rough and rowdy, bigger than me and barely literate.

I was lousy at sports and a wimp on the playground. I was always in the Crows in singing class. I had to stand out in the corridor with the Jehovah’s Witnesses when the class sang God Save the Queen and recited The Lord’s Prayer. I had to sit out while they learned to dance in Phys. Ed. and learned about sex in Health. I was entranced by the girls, but afraid to speak to—let alone play with—them. I hung around the edges of things, much like my ghostly eldest brother.

We often went to my grandparents’ place in Waterloo for our vacations—Christmas, sometimes Easter, and usually a couple weeks in the summer. If my dad couldn’t get off work, Mom would somehow find a ride with somebody who was heading down that way: she and her 5 kids crammed into the back seat for the 10- or 12-hour journey “home.” Our times in Waterloo County were usually a whirlwind of visits with all the relatives. Unlike my siblings, I had no cousins my age, and I wasn’t really close to any of them, but I’d often end up spending a few days in the home of some aunt and uncle I barely knew, homesick and struggling to decipher the strange habits and rhythms of my cousins’ lives.

Every summer, Dad would take some time off to go camping. He loved the outdoors, and he loved fishing. We had a big orange canvas tent that we’d pitch at Echo Lake or Twin Lakes on St Joe’s Island. Dad would rent a boat, put his old 5-horse Johnson outboard on it, and go out fishing, taking any of us who were willing to go. My mom and the others would hang around the campsite, reading, paddling in the water, or playing on the beach.

Dad was not a patient man, and I could never get the hang of casting. I never caught a fish and couldn’t see the point of just sitting in a small boat in the sun all day, bothered by mosquitoes, worried about storm clouds. But it was better than the ice fishing, when we’d be huddled out on Lake Superior in our thin ski jackets and rubber boots and home-knit mittens, freezing as the sun set in the late afternoon behind the rim of ice. In both cases, I endured the misery only for the opportunity to be doing something with Dad.

§

Perhaps it is because they are relatively rare that I remember my times with Dad so vividly. He gave me access to a different world than my mother’s. It was Dad who helped me realize I could fix things. I remember one evening helping him disassemble and repair the coaster brake from one of my bicycles on the back porch. He showed me how the parts went together and where to put the grease (probably Vaseline) and explained how the brake worked. Later, he showed me how to change spark plugs and set the points on his car.

I would sometimes hang around the garages where he worked on the trucks he drove: changing the oil, fixing the brakes, or overhauling an engine. Because he worked for fly-by-night operators during the 60s, most of the garages were awful places, old warehouses with dark puddles in the corners and rats scurrying around in the trash piles. He and the other drivers worked on the trucks under feeble lights, getting me to fetch tools or rags, swearing and laughing, and drinking beer when they took breaks. They were always friendly with me, giving me bottles of Coke and teasing me.

Once in awhile, I was allowed to go on a trip with Dad in his truck. It was wonderful, heading out into the night way up in the cab of that roaring machine, stopping in truck stops for hot hamburger sandwiches, going to places I’d never been before: Hamilton, Windsor, Muskegon, Grand Rapids. But it was also terrifying, being away from the familiar rituals of Mom and home, conscious of the 50 tons of steel or lumber on the trailer behind, worried that Dad would fall asleep or enter a curve too fast. And I always had to pee, but was afraid to tell Dad, to force him to pull over on the soft shoulder of the highway.

§

As it turned out, we got home safely every time. Both Dad and I survived my childhood, perhaps thanks to Mom’s prayerful intervention.

I somehow managed, out of all of this, to cobble together a persona: about grade 6, I adopted the role of class clown, with little respect for rules or authority and with what I thought was a clever and cynical wit. That carried me, not especially happily, through high school.

—Rick Martin

.