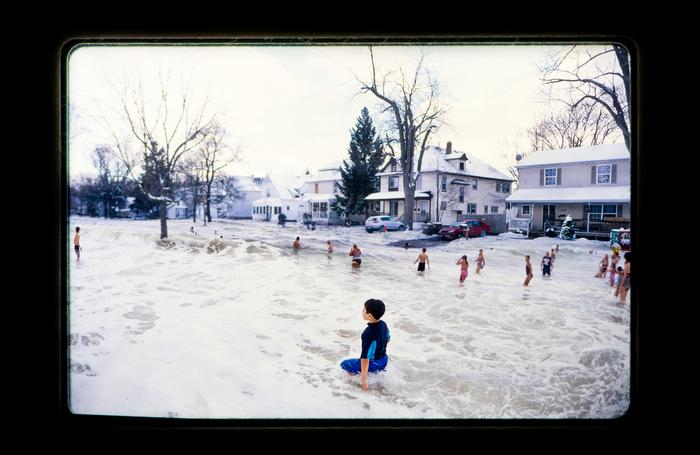

Michigan (2016) —Mark Reamy

Michigan (2016) —Mark Reamy

.

This is the first issue of the eighth year of publication for Numéro Cinq, an astonishing and unexpected turn of events, neither foreshadowed nor forwarned in the long gone early days when we thought we’d do this for six months tops. The cover image for the issue is from Mark Reamy, a brilliant discovery brought to us via the scouting efforts of Contributing Editor Rikki Ducornet. Reamy’s unsettling, hybrid images are both surreal and prophetic, counting the days before the ice caps melt completely the the oceans quietly lap the sandy shores of Utah. This fits the issue line up in more ways than I can list.

Headliners this month include the illustrious Dawn Raffel doing a stint as a guest reviewer at NC, writing about Samuel Ligon’s Among the Dead and Dreaming, and the legendary poet Donald Hall interviewed for us by Allan Cooper, who also contributes a review of Hall’s The Selected Poems of Donald Hall.

From Ireland this time, we have a gorgeous, lively story by Mia Gallagher about an eccentric Dublin hooker, her biscuit-tin money box and a snake named Kaa.

But besides the Gallagher story, we have an epic haul of fiction in this issue — stories by John Madera and David Huddle and a novel excerpt from Eugene Mirabelli. And a first publication by Laura Fine Morrison who wrote for us a delightfully winsome makeover of Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” — a little African boy turns into a yam.

We also have poetry — an epic haul, a veritable flood — from the inimitable Kathy Fagan, also Mary di Michele from Canada, Stuart Barnes from Australia, and Alison Prine. And our translation this month is a selection of poems by the Slovenian poet Marjan Strojan (scouted for us by Contributing Editor Sydney Lea).

Gary Garvin contributes an essay on Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” that cannot escape contemporary parallels. Laura Michele Diener has a poignant essay about her beloved father, ailing with dementia. And Noah Getavackas, who has been here before, continues his satiric progress through the great philosophical and religious works of the West.

We have more reviews. Frank Richardson on Thus Bad Begins by Javier Marias, Jason Lucarelli on Assisted Living by Gary Lutz.

And there is more! Late and or feverishly awaited. Perhaps this month we’ll get a new NC at the Movies.

As usual, it’s a miracle we made it.

Mia Gallagher

Mia Gallagher

I picture her not on the canal, but across the city, on the other strip; the Golden Mile near Heuston train station. Sun slants over the low roofs, striping the Liffey gold. A man pulls up in his Punto, winds down his window. Another girl is nearer but the man beckons to Susie, smiling his slow, investigative punter’s smile. Susie leans over. A waft of fag smoke, sweat and Magic Tree. —Mia Gallagher

Kathy Fagan

Kathy Fagan

I went out looking

at Europe & all its stones

its diagonal churches & bronze

horses my shoes clattering like their

shoes my eyes as wild

If the heart is a cup

if coins are diamonds

well then we are

full & we are rich

—Kathy Fagan

Samuel Ligon

Samuel Ligon

In Ligon’s world, every emotion and impulse shimmers with its opposite, every moment is saturated with the consciousness of others, and every boundary is subject to erasure—as when Mark says of Cynthia, “Her presence was everywhere and then her absence, and then her presence again, so that her presence and absence felt like the same thing.” —Dawn Raffel

Dawn Raffel

Dawn Raffel

Donald Hall

Donald Hall

My lowest point coincided with my divorce and five years of booze and casual promiscuity before I met and married Jane. When we were first married, it took me a while to get started. Actually I wrote the first parts of The One Day, although I couldn’t bring it together for another dozen years, and started “Kicking the Leaves” (the poem not the book) before leaving Ann Arbor to move into this New Hampshire house. Here the place and the marriage to Jane flowered, and I wrote the book Kicking the Leaves, with my horses and my cows et cetera. It was my breakthrough. —Donald Hall

Allan Cooper

Allan Cooper

Laura Fine Morrison

Laura Fine Morrison

My body began to transform anew. Dark blotches established themselves on my skin. A crack developed in my side, with a crusty edge that flaked off to reveal more discolored tissue below.

At Mother’s request, Grandfather came by to evaluate my condition. He ran a thickly calloused finger along the fissure. “Yam rot,” he confirmed.

Mother twined her fingers. “Can he be saved?” —Laura Fine Morrison

Gary Garvin

Gary Garvin

We contemplated her gaze and that gesture, at least for a while, as she faced us, the smiling Army Specialist Sabrina Harman, who aided in the gathering of intelligence at her station, Abu Ghraib, the prison deep inside occupied Iraq. Or rather we saw her in pictures brought to light after years of subtle horrors in a war we thought was going well and whose mission we were sure of, the pictures bringing a clarification, an obviousness, a relief, their own kind of rightness. She does not look at what she smiles over or what she thumbs up but we see them, the pile of grotesquely hooded, naked men, the blackened corpse. —Gary Garvin

Laura Michele Diener & father

Laura Michele Diener & father

About the time when my father, Abraham Morganstern, started to lose his memory, he began to sort through the household trash on a daily basis, picking out with surprising care bent hangers, sole-less shoes, cracked mirrors, unattached buttons, and other items he deemed worthy of resuscitation. His triumphant scavenging at first irritated my mother, Hadassah Morganstern, and me when I happened to return for a visit to the ever-more-cluttered house of my childhood, but after a while we both accepted it as a permanent facet of his new personality. I suppose if you are falling away into some sort of mental darkness, you hold onto anything concrete, even if it’s broken. —Laura Michele Diener

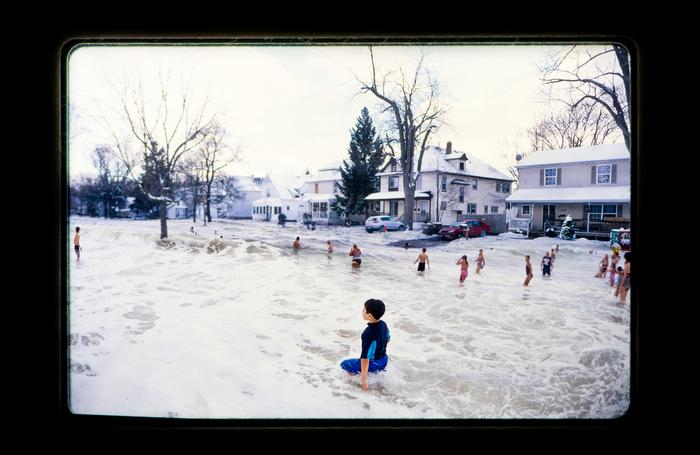

Beach Day (2016) —Mark Reamy

Beach Day (2016) —Mark Reamy

I believe every photograph is a memory, an exact moment of time and space. By combining photographs, I am conflating accounts, adding them together and forming new stories. Domestic interiors are overrun with something unexpected, something other. The incredibly banal shifts into the transcendent, and so on. I’m interested in how the present influences the past, and I’m investigating why we selectively remember or forget. I’m fascinated that our history is constantly changing, that something so seemingly concrete can slip away. I welcome the surreal, psychedelic and uncanny. —Mark Reamy

Mark Reamy

Mark Reamy

Marjan Strojan

Marjan Strojan

So, in the cobwebs of Saint Petersburg’s

Railway Station (in snow) Madame Karenina

still waits to throw herself under a train.

And I’ll probably never find out what Vronsky

could have done at the time, if anything.

Tatiana never finished her letter, though I presume

she had turned down the poet, who ages ago,

in his small neat hand, had been scribbling

in his notebook the names of his lovers.

—Marjan Strojan

Mary di Michele

Mary di Michele

when my mother started to lose her memory she kept

this photo in her pocket; it’s folded into quarters

and badly creased. Some might say it was ruined. Red mail truck, red

mailbox, it’s a cheerful colour on a dull day in No

Damned Good. How did I get here? I grow old, I grow old, I

will wear the bottoms of my blue jeans rolled.

—Mary di Michele

Alison Prine

Alison Prine

You said, watch the wood storks as they circle,

their grace disappears so utterly when landing.

Hard to decipher the dank smell of the paper mills

from the old salt of the marshland.

Soon we’ll forget both and in our absence

the nests of these egrets will fall, stick by stick.

—Alison Prine

Stuart Barnes

Stuart Barnes

High tide: the drunk drops a line where salt

water, fresh converge: subtropical trompe

l’oeil: honeyeaters squeak on asphalt,

stab redly at chalk grapes: the Coral Sea, salt

like speech, scallops trawlers, fault on fault:

sudden whoosh, O God! from mangrove swamp:

the meth head rehydrates the brat: sugar, water, salt:

the black hour pitches: four thousand bats tromp.

—Stuart Barnes

David Huddle

David Huddle

After I moved out, I got pretty crazy and went into what I’ve thought of as my “Sound of Silence” phase. I listened to that song a lot, but it was “The Boxer” that I fixated on. The verse of it about the whores on Seventh Avenue just kept ripping my heart out. For several months I was at its mercy. I needed to feel the pain of it again and again. —David Huddle

Gary Lutz

Gary Lutz

Sort of heartbreaking is the girl’s response if you fuss with it, and you must because meaning-making is up to you. Has it been years since she loved only once? This is as funny as it is sad. Her phrase widens the gap that has been there from the beginning. She shows her age, her lack of experience. The narrator’s hurts turn out to be worse than hers. —Jason Lucarelli

Javier Marías

Javier Marías

We all have secrets. We all have secrets we would never divulge and secrets we wish had never been revealed. That we cannot fully know another is axiomatic, that we deny our own history and the histories of others, commonplace. Where, then, the place for truth? We live in a time when the Oxford Dictionaries awarded “post-truth” word of year. —Frank Richardson

Eugene Mirabelli

Eugene Mirabelli

It’s a privilege to love someone and I loved Alba. “I’m so happy you found me,” she used to say. I was handsome, her man from the sea, and the one she loved best in the whole world. She’s gone, so I’m not handsome anymore. I’m an old man driving home with a pizza and I’m sobbing because some cheerful asshole is singing on the radio about his love who is gone beyond the sea and the moon and stars, but she’s waiting and watching for him, and someday he’ll find her there on the shore and they’ll be together and he’ll embrace her, just as he did before.—Eugene Mirabelli

.

.