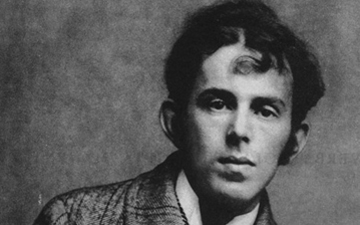

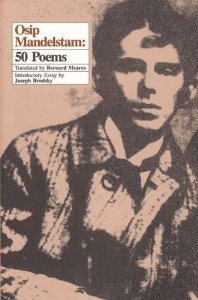

Poetry is a fickle profession. The muse is fickle, the audience is fickle, fame is fickle. Critics and scholars have Alzheimer’s — the one-time darling is often simply forgotten. This happens to an author whether his or her work deserves neglect or not; great poets go down before the scythe of forgetfulness. Today NC is launching a new series called Undersung to try to fill in some of the gaps for the dementia-riddled reading class. Contributing Editor Julie Larios suggested this, and there is none better to write the series because she has a reading memory like a wolf trap and can call to mind verse at the drop of a hat. She is also just really smart about the technical aspects of a poem. And she has her favourite neglected poets to whom she brings brio and passion. Today, we have George Starbuck, the man whose manuscript beat out Sylvia Plath for the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1960 but whose life was less notorious. Often wrongly pigeonholed as a light verse poet, he was a technical master and superb ironist. He should not be forgotten.

dg

—-

“Do not go into the light,” the woman screams. “Stop where you are. Turn away from it. Don’t even look at it.” Fine advice, if your name is Carol Anne and you’re the victim of a poltergeist. Listen to your mother as she shouts to you through the television static. Believe her: The light is not your friend.

But in poetry, you might be better served by ignoring the voices that discourage the light (verse, that is) in favor of the dark, or that denigrate the light in favor of what is “heavy.” As in “Wow, that’s heavy, man.” For “heavy,” you’re expected to understand significant and serious; it weighs something and is important and has a chance at entering The Canon. It should not (repeat: should not) make you laugh. And it probably should not come wrapped up in anything sneaky that makes you think what you’re reading is dandy candy but then turns out to be good for you. That’s not fair.

Enter the poetry of George Starbuck, once named “the thinking man’s Ogden Nash.”

His reputation for “light” verse (a misnomer, I think – if that’s what it is, then Starbuck’s version of it is a sledgehammer disguised as a feather) kept him out of several of our most important anthologies and thus out of Poetry 101 classes across America. Actually, one of his poems (“A Tapestry for Bayeux”) did make it temporarily into the influential Little Treasury series edited by Oscar Williams, but was dropped from the anthology (and Starbuck “consigned to a special poetic oblivion,” according to poet Anthony Hecht) when Williams was informed that the initial letters of the first 78 of 156 lines spelled out “Oscar Williams fills a need, but a Monkey Ward catalog is softer and gives you something to read.” Who does that, writes a brilliant poem about naval operations during WWII, and builds in an acrostic poking fun at the anthologist who can make or break your reputation? George Starbuck, that’s who.

A Tapestry for Bayeux

1. Recto

Over the

….seaworthy

cavalry

….arches a

rocketry

….wickerwork:

involute

….laceries

lacerate

….indigo

altitudes,

….making a

skywritten

filigree

….into which,

lazily,

….LCTs

sinuate,

….adjutants

next to them

….eversharp-

eyed, among

….delicate

battleship

….umbrages

twinkling an

anger as

….measured as

organdy.

….Normandy

knitted the

….eyelets and

yarn of these

….warriors’

armoring—

….ringbolt and

dungaree,

….cable and

axletree,

tanktrack and

….ammobelt

linking and

….opening

garlands and

….islands of

seafoam and

….sergeantry.

Opulent

….fretwork: on

turquoise and

….emerald,

red instants

accenting

….neatly a

dearth of red….

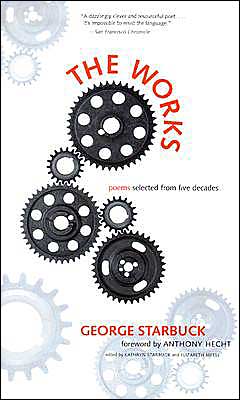

On it goes, for twelve 13-line stanzas, every single line three syllables, accent always on the first syllable (dactylic monometer.) And it makes sense, in terms of its subject matter. And the language – vocabulary, music – is brilliant. And it’s an acrostic. As Hecht says in his introduction to The Works, published after Starbuck’s death, it is a poem of “needlework intensity.” Starbuck himself, in this poem, praises “opulent fretwork.” Of course, that might be exactly the problem. Fretwork and needlework are delicate, and American poetry – as with many things American – prefers muscle.

Perhaps no one needs to scream at us to stay away from the light. After all, we’re culturally drawn to the dark side, James Cagney with his tommy gun, Bruce Willis with an AK-47, aren’t we? It’s often High Noon in America, and whoever comes out of the fight alive wins; America seems, even in the year 2013, predestined to favor the gunslinger over the Quaker (as Starbuck says, “Saturday night’s a longshot / Contraption as it is. / A man without a Magnum’s / A piece of agribiz. // He might as well push daisies / And model for a wreath / And pick a granite afghan / To cuddle up beneath.”) Arnold Schwarzenegger takes out Fred Rogers in the first minute of the first round, no doubt about that.

Heavyweights rule the American roost. Farther down in the pecking order come middle and welter, then featherweight, and even farther down is the pesky bantam. Does flyweight even need to be mentioned? The boxing analogy holds for poetry: The lighter the fighter, the smaller the size of the prize. Come to think of it, the analogy holds for theater and film, too – Sean Penn’s suffering father in Mystic River gets the 2003 Oscar over Bill Murray’s sardonic film star in Lost in Translation. Who said comedy is king?

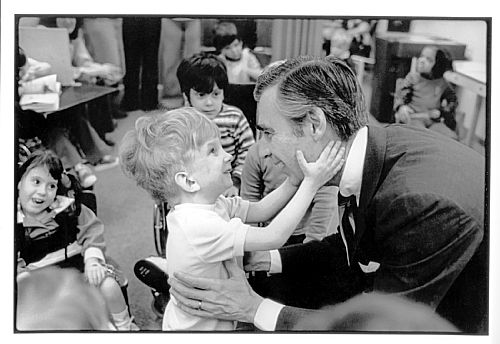

Anne Sexton, definitely a Canon-weight poet, once wrote “I have to be great,” and many people admired her and still admire her for it. Ambition is more attractive to some people than it is to others. (My own reaction, when I read those words: Imagine an artist thinking that, much less confessing it – unless confession is your thing.) Fellow poet Starbuck – who was Sexton’s lover early on while she honed both her poetry and her appetite for fame – seemed not to care as much about the size of his pistol or his reputation, nor did he spend time thinking about categories like welters, bantams, flies and feathers, not unless he could turn the words themselves to good use with a clever rhyme (feathers / weathers / death spurs / breath verse / meth purrs…no, I can’t do it, not the way George Starbuck could.)

This rhyming thing is hard, god-awful hard if you want to do it with panache; that’s why so many poets, caring not just about the basic message of a poem but about the messenger’s ability to deliver it in a breathtaking way, appreciate George Starbuck’s gifts.

Fable for a Blackboard

Here is the grackle, people.

Here is the fox, folks.

The grackle sits in the bracken. The fox hopes.

Here are the fronds, friends,

that cover the fox.

The fronds get in a frenzy. The grackle looks.

Here are the ticks, tykes,

that live in the leaves, loves.

The fox is confounded,

and God is above.

Technically dense, emotionally delicate, intellectually profound. Try doing that – hitting that trifecta. He was a poet’s poet, as they say. And Starbuck himself said, about his choices, “For me, the long way round, through formalisms, word-games, outrageous conceits (the worst of what we mean by ‘wit’) is the only road to truth. No other road takes me.” His obituary in the New York Times echoed the sentiment: “If the scope of his verbal talent sometimes seemed at war with his reputation, Mr. Starbuck could not seem to help himself.”

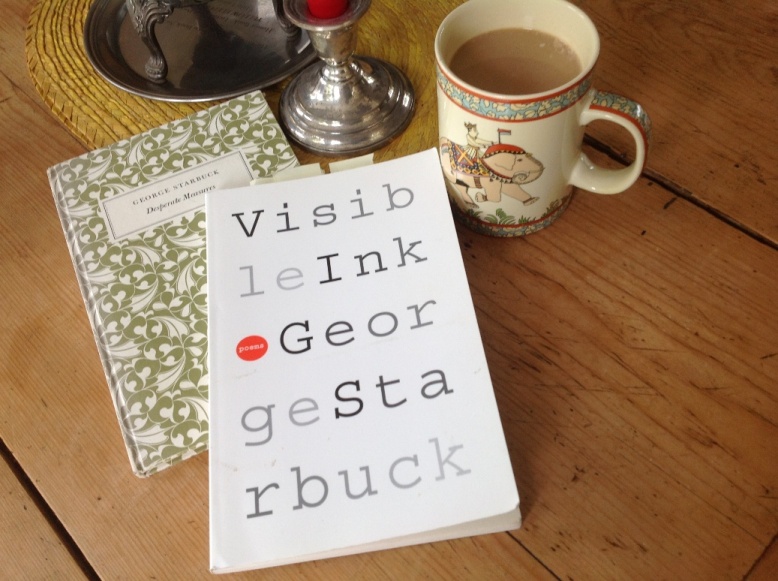

If you haven’t read his work, do so. He published individual poems widely during his lifetime and gathered them into books only occasionally (two excellent collections, Visible Ink and The Works were put together by his widow and published posthumously.) His first collection, Bone Thoughts, was awarded the Yale Younger Poets prize in 1960. Sylvia Plath’s manuscript for The Colossus competed with Starbuck’s that year; they studied together (along with Sexton) in one of Robert Lowell’s famous workshops at Boston University. Plath, in her journals, rails against losing out to Starbuck.

Certainly, not everything Starbuck wrote for that first book would be considered light verse, though it did produce an introduction by the judge – the critic Dudley Fitts, who took over the Yale Younger Poets series from W. H. Auden — which indicates Fitts didn’t quite know what to think of it. Not only did Fitts state, in that introduction, that Starbuck was “a man awake in the nightmare of our day” and predict that “a great song is begun,” but he also wrote, “I was also attracted, and sometimes repelled, by Mr. Starbuck’s wit….[He] could use an intellectual sedative.” Fitts cites this poem as an example:

War Story

The 4th of July he stormed a nest.

He won a ribbon but lost his chest.

We threw his arms across the rest

…………..And kneed him in the chin.

…………..(You knee them in the chin

…………..To drive the dog-tag in.)

The 5th of July the Chaplain wrote

It wasn’t much; I needn’t quote.

The widow lay on her davenport

…………..Letting the news sink in.

…………..(Since April she had been

…………..Letting the news sink in.)

The 6th of July the Captain stank.

They had us pinned from either flank.

With all respect to the dead and rank

…………..We wished he was dug in.

…………..(I mean to save your skin

…………..It says to get dug in.)

The word when it came was three days old.

Lieutenant Jones brought marigolds,

The widow got out the Captain’s Olds

…………..And took him for a spin.

…………..(A faster-than-ever spin:

…………..Down to the Lake, and in.)

Unfortunately, Fitts’s early assessment in 1960 turned out to be the final critical assessment when Starbuck died of Parkinson’s in 1996: Critics admired his work (perhaps not as much as fellow poets) but were unnerved by it because tonally and technically it was so complex, at once delicate and obsessive, intricate and blunt, playful and brutal. After an extended time with it, even a respectful reader becomes exhausted, or better said suspicious, and a real tumble of questions begins to overtake the pleasure: If it is “bravura technique” (as Hecht says – and he goes on to say “it has no match among English-language poets of this century”) does it come from the heart or is the poet himself intoxicated with formal intricacies? Does the man never come up for air and write a more relaxed poem? Do the technical restrictions inflict a straightjacket on the poet rather than provide a source of inspiration? In fact, is it a poem or is it a math puzzle? Starbuck began his university studies at Cal Tech in mathematics at only 16 years old – was he more interested in mathematical patterns or in poetry? Even the cover of his collected work shows us a system of interlocking gears, more mechanical than human:

Maybe the answer to both parts of all the questions above is yes…and yes. One of my favorite poems in the book (“Unfriendly Witness”) begins this way: “I never played the Moor, / I never looked to see, / I don’t know what my hands are for, / I know they’re not for me” and ends with this: “And yet the world is heavy / and filled with men like me—/ with tired men, with heavy men / that slip my memory / if that be perjury.”

We hear a nursery rhyme in the treble clef of “War Story” and “Unfriendly Witness,” but there is no doubt they are serious poems, with a bagpipe-type dirge underneath the melody.

Ahh, “serious.” There it is again, that word. Can a poet who says in his poems “Love is a strange coot” and who indulges extravagantly in clerihews and double dactyls ever be taken seriously? Take this double dactyl from “Troves from the Natives of 1992”:

Higgledy piggledy

Fifty Columbuses,

Fifty times richer in

Trinkets and beads

Couldn’t provision the

Quinquecentennial

Memorabilia

Business’s needs.

Far be it for Starbuck, of course, to be satisfied with one complete double dactyl; instead, he continues this poem for another eight stanzas (four more complete double dactyls) in a tour de force of the form, which requires not only the double dactylic line for each 4-line stanza, but a six-syllable single word, often as the entire second line of the second stanza. Notice how one six-syllable word is followed by another in the Starbuck excerpt – “quinquecentennial memorabilia” – which few poets could pull off.

Starbuck goes for those multisyllabic lines with gusto: “miniconquistadors,” “made-in-Rumania,” “demimillennial”…that’s where the challenge and the fun of the form come together and burst into flame, and that’s where you’ll find Starbuck at his game-playing, neologistic best. Does he self-combust? The answer to that is a matter of taste, a little like the fried grasshoppers sold by the handful in Oaxaca – tasty but scary. Fitts, remember, was both delighted and repelled, and Starbuck is an acquired taste, that’s for sure. He was, as one NPR commentator described him, “high bard of the big pun and the even bigger idea.” That’s a heady and unusual mix. Sometimes you want to stand back from that kind of chemistry.

George Starbuck should be well-known to anyone who writes and teaches. When he was just a young man working at the library of SUNY-Buffalo, he was fired for refusing to sign the loyalty oath required of all employees. Starbuck recognized the repressive abuse of power inherent in New York’s Feinberg Law (enacted in 1949) which sought out teachers who used “propaganda” in the classroom on “children in their tender years.” Three faculty members joined Starbuck in suing the university, but it was Starbuck himself who was the acknowledged instigator of the suit (this is well-documented in Marjorie Heins’s Priests of Our Democracy: The Supreme Court, Academic Freedom and the Communist Purge.) Ultimately, the case was taken up by the Supreme Court, which ruled in the group’s favor and found the law unconstitutional. Starbuck remained a fiercely committed political activist, most visibly in his opposition to the war in Vietnam. For a blistering example of that, read his poem, “Of Late,” addressed to Robert McNamara, about Norman Morrison, the Quaker who burned himself alive to protest the war (he “…burned and was burned and said / all there is to say in that language.”) You can see the whole poem here.

A read-through of obituaries which followed Starbuck’s death at age 65 is impressive: He studied for two years at UC-Berkeley, three years at the University of Chicago (where he met and became friends with Philip Roth, whose work he later edited for Houghton Miflin), a year at Harvard, and additional time at the American Academy in Rome, never earning even a BA degree. He was an inspirational teacher at SUNY-Buffalo, the Iowa Writers Workshop and (returning to his roots) Boston University. Both Maxine Kumin and Peter Davison studied under him. He won the coveted Lenore Marshall Prize in 1983, administered by the Academy of American Poets (other winners have been Mary Oliver, Philip Levine, Stanley Kunitz, John Ashbery, Robert Pinsky, Adrienne Rich, C.D. Wright – the entire list reads like a Who’s Who of American Poetry.) He invented an entirely new poetic form called the SLAB, a “Standard Length and Breadth” poem written in fourteen-letter lines that form a “slab,” typographically as does this excerpt from one SLAB entitled “Cargo Cult of the Solstice at Hadrian’s Wall” [Note: slabs are at their best using Courier font, which lines up precisely]:

OTinyBombOTiny

BombWhatGangOf

MadmenMadeThee

OMiddleeastern

MasterpieceNoT

NTBetrayedThee

OEensieWeensie

IndyCarOCreamy

HalvahCandyBar….

Well, as I’ve said before, it goes on for quite a few more stanza. Or slabs. The man was unstoppable.

There are a few poets who “played” (read “worked”) with language the way Starbuck did. John Hollander and Anthony Hecht, his contemporaries, famously invented the double-dactyl, which Starbuck took up with glee. The British poet James Fenton, slightly younger, found the same strength in nursery-rhyme rhythms, especially in his anti-war poem, Out of the East:

Out of the South came Famine.

Out of the West came Strife.

Out of the North came a storm cone

And out of the East came a warrior wind

And it struck you like a knife.

Out of the East there shone a sun

As the blood rose on the day

And it shone on the work of the warrior wind

And it shone on the heart

And it shone on the soul

And they called the sun – Dismay.

I sometimes hear Fenton as I read Starbuck, though I find myself missing Starbuck’s humor. Auden often had both light and dark in the same poem, as in his poem “As I Walked Out One Evening,” which starts out with its Mother Goose images this way:

As I walked out one evening,

Walking down Bristol Street,

The crowds upon the pavement

Were fields of harvest wheat.

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway:

‘Love has no ending.

‘I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you

Till China and Africa meet,

And the river jumps over the mountain

And the salmon sing in the street,

‘I’ll love you till the ocean

Is folded and hung up to dry

And the seven stars go squawking

Like geese about the sky.

Like Starbuck, Auden provides us with a light melody at the surface, and a funereal bass-clef as the poem proceeds:

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

‘O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.

‘In the burrows of the Nightmare

Where Justice naked is,

Time watches from the shadow

And coughs when you would kiss.

‘In headaches and in worry

Vaguely life leaks away,

And Time will have his fancy

To-morrow or to-day.

Both Auden and Starbuck manage to use child-like rhythms to subvert our expectations – and subverting expectations is an important element in poetry. Starbuck, however, gave himself permission to be more relaxed with breaks in the rhythm, as well as to break words in two at line endings, and to invent words in order to reach a rhyme, as these lines do from his poem “Dylan: The Limerick”:

He did his Old-Man-Memphis

Empathy with emphys-

…………..Ema schmooze.

Did his minstrel Ham-and-Shem fuss.

Did THE OLD MAN’S ABM FAC-

ILITY DEEMPHAS-

…………..IS BY DEMOLITION BLUES.

…………..He brung the teenyboppers their bad news.

Starbuck’s rambunctious combination of Low Culture and High Culture has become more common in the postmodern, post-9/11 poetry world – I’m thinking of the recent work of poets like Richard Kenney, who can be equally witty, compressed and riveting, and sometimes equally hard to parse:

March

Sky a shook poncho.

Roof wrung. Mind a luna moth

Caught in a banjo.

This weather’s witty

Peek-a-boo. A study in

Insincerity.

Blues! Blooms! The yodel

Of the chimney in night wind.

That flat daffodil.

With absurd hauteur

New tulips dab their shadows

In water-mutter.

Boys are such oxen.

Girls! — sepal-shudder, shadow-

Waver. Equinox.

Plums on the Quad did

Blossom all at once, taking

Down the power grid.

Another poet who comes to mind is Cody Walker. I read him with the same pleasure as I do George Starbuck. Walker is not afraid of going for a laugh, and in his book Shuffle and Breakdown he tosses in those same wry High/Low Culture references that not every poet is brave or crazy enough to make:

With Ms. Rule on One Arm

Impolitic as it may sound,

gimp-witted idiots abound.

They give the lexicon a whirl.

The get the gasworks and the girl.

MacArthur? Guggenheim? Booby

prizes, we find. Better to be

a stumbler, a throttlebotom.

Lower our eyes. And don’t dot ‘em.

Sometimes the work of Kay Ryan, a recent Poet Laureate, takes on rhyme in a similar, playful way:

Lime Light

One can’t work by

lime light.

A bowlful

right at

one’s elbow

produces no

more than

a baleful

glow against

the kitchen table.

The fruit purveyor’s

whole unstable

pyramid

doesn’t equal

what daylight did.

But Starbuck was unique. So why have so many people never heard of him? Well, as one obituary pointed out, he indulged in such a “dazzling display of pun, parody and pyrotechnic wit that critics sometimes seemed too busy laughing out loud to take him seriously….” Starbuck tried to excuse his weakness in one stanza of a long poem titled “Tuolomne.”

I have committed whimsy. There. So be it.

I have not followed wisdom as I see it.

You avalanche me sermons and I make

Rhymes for the sake of rhymes.

This sinner, Lord, of his lamented crimes.

That poem is from his 1978 collection Desperate Measures – even Starbuck’s titles are double entendres. The poet Eric McHenry suggests you have three cups of coffee as a way to prepare for reading the buzzy, caffeinated work of George Starbuck. I suggest you do just that: Sit down, sip, read, marvel.

—Julie Larios

——————————–

Seattle poet Julie Larios has had poems published in a variety of print and online journals. Her work won a Pushcart Prize and has been selected twice for inclusion in the Best American Poetry Series. Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University on July 13th.

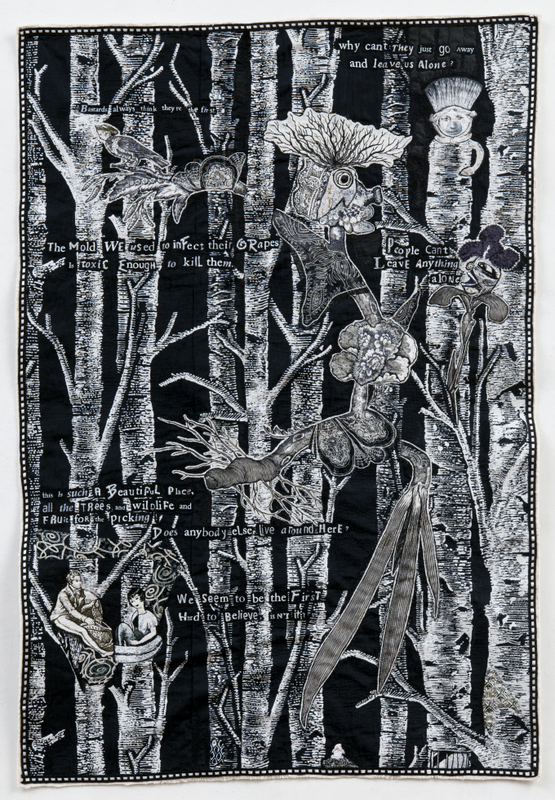

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011

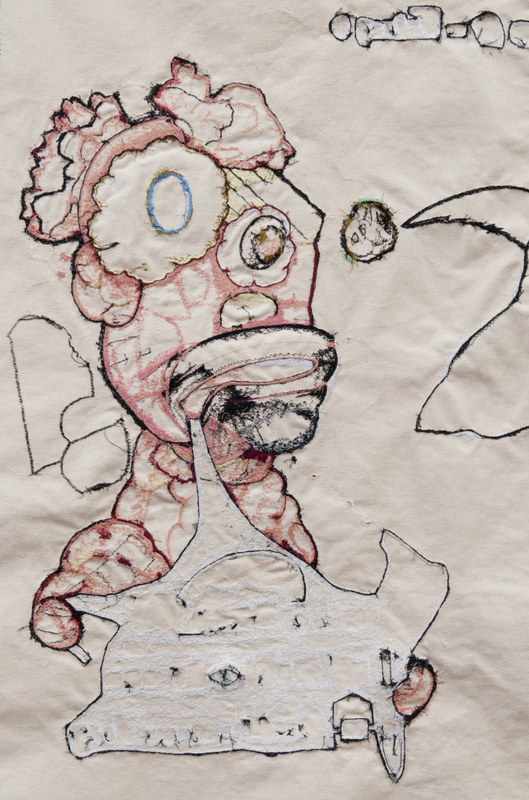

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011 Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

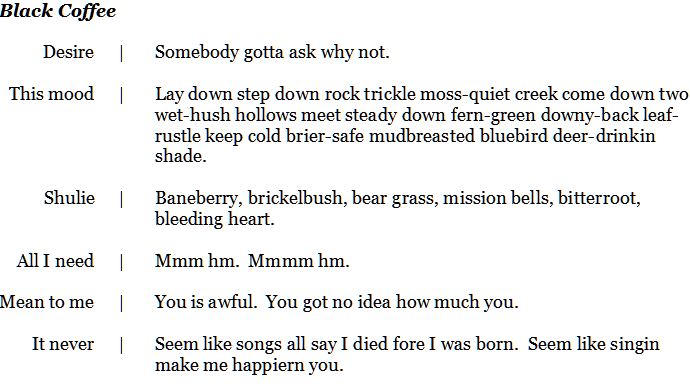

The Language of Flowers, 2012

The Language of Flowers, 2012