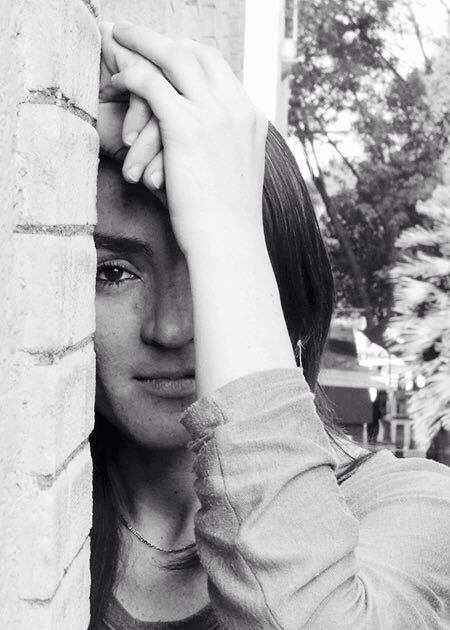

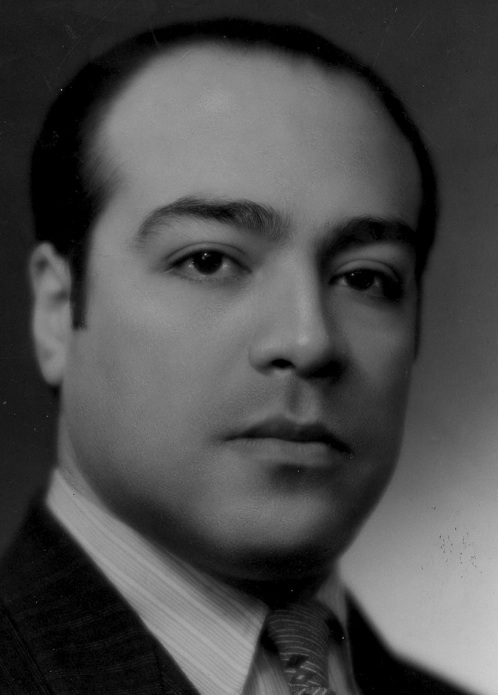

Elsa Cross

Elsa Cross

.

This month’s edition of Numero Cinco finds our newest addition to the NC masthead, Dylan Brennan, speaking with translator Anamaría Crowe Serrano about her work with Mexican poet Elsa Cross. They discuss Serrano’s involvement in bringing Cross’s work to an English audience, as well as the difficult decisions translators must make when doing so.

After the interview, we have a selection of poems by Cross, both translated from the Spanish by Serrano and in their original language.

— Benjamin Woodard

.

Dylan Brennan (DB): How did you get involved in this project?

Anamaría Crowe Serrano (ACS): I’ve been involved with Shearsman Books for several years, first with a collection of my own, and then with translations of some of Elsa’s poems that were included in a Selected Poems in 2009. The editor, Tony Frazer, publishes several titles in translation every year – as well as collections in English and the Shearsman poetry journal – and at some point he asked if I’d be interested in expanding on the original translations I had done. I didn’t have to think about it twice.

DB: How much did you know about Elsa Cross beforehand and how much did you have to learn as you went about translating?

ACS: I had met Elsa in London at the launch of her Selected Poems, so I knew a little about her. She teaches philosophy of religion and comparative mythology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and has published extensively, but I am always curious about the person behind the biographical note. It’s a bonus when I can make some connection with the poet I’m translating because I like to enter the poet’s world. In some ways translating is a little bit like method acting – for me, anyway – in that I like to absorb the poet and his/her mood if I can, in order to translate the work as faithfully as possible. It means that I adopt a slightly different persona each time I translate a different poet, and it’s one of the reasons why I’m not particularly experimental with the text of the translation itself.

What struck me about Elsa during our conversation in London was that her poetry reflected her personality: gentle, contemplative, self-assured. It seemed that the mysteries and uncertainties inherent in the world around us, which philosophy constantly probes, rather than cause angst, in some paradoxical way provide a source of strength for this poet. I got a sense that she accepts that not everything can be known, and there’s comfort in that place of acceptance. The idea of immersing myself for several months in Elsa’s poetic world and worming my way through her raw material was very appealing. As I’ve said, I had already translated some of the first section of Beyond the Sea, so I was familiar with Elsa’s style as well as the setting for the poems. Her collections are often written against the backdrop of a particular locale which works as an anchor for her thoughts. In Beyond the Sea, we find ourselves in Greece. The sound of waves, cicadas in the afternoon heat, plants stirring in the breeze, wings flapping, ancient ruins, are a constant accompaniment, like a leitmotif, to the philosophical thoughts and questions posed in the poems.

DB: Did you get in contact with Elsa Cross to discuss the poems? If so, how was that? Did she have any role in the translation process?

ACS: Yes, I did. I think all translators have questions about the text, so it’s an advantage to be able to ask the poet directly. In this case Elsa was very generous with her answers, clarifying specific words or images or nuances, such as what kind of “filo” she meant in the first line of poem 5 of “Dithyrambs”. I wasn’t sure if it might be a blade, a trickle of some sort, a thread… It’s wonderful to be able to consult the author because it means that the end result is as close to the intended meaning of the original as it can be; there’s very little guess work on the translator’s part, although individual lexical choices and phrasing are ultimately subjective. In my experience, poets are always happy to collaborate with the translator if they can because a translation can seem quite alien to the poet. Poets get attached to their specific lexical choices and even to the spaces between them. Every word of the original is so charged for the poet that it can be a terrible disappointment to realise that the translator has misinterpreted something that is very meaningful to you as a poet. Having some control over the translation process goes a long way towards assuaging those concerns.

Elsa’s English is excellent, which meant she could make very useful suggestions. The draft translation that was emailed from Dublin to Mexico City and back many times is peppered with comments ranging from uses of the definite article or prepositions or possessive adjectives, to whether the translation should include footnotes for words such as “tezontle”, to what the subject of a particular verb is (given that it’s not always specified in Spanish, which can sometimes allow for ambiguity, whereas it must be specified in English, destroying the ambiguity).

Over the years I’ve come to think of a translation as the child of both the author and the translator. A translation contains the linguistic DNA of each through a process that explores language at a microscopic level. When the translator can work with the author, the symbiosis is more complete: the child resembles both its parents more closely than it might had there been no collaboration between them. In Beyond the Sea, Elsa’s input was so valuable that I suggested the cover should read “translated by Anamaría Crowe Serrano with the author”, but she was too modest to want to claim any credit for the translation.

DB: Is translating poetry something you find easy or do you find it agonizing at times? What about the Greek elements of the book? Something you had to research or was it all known to you already?

ACS: Sometimes you come across a poem that you can translate quickly; the words just come to you and the result is satisfying. But those occasions are rare. Usually it requires many hours of thought – more than might seem apparent from the length of a poem. The end result that appears in print is just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that tip lies the bit the reader never sees – the process – which for a collection could be up to a year’s work. But I absolutely love translating. (The only thing I agonize about is the inadequate pay, completely out of line with the hours and skill involved in the process.) Lines or words that are problematic might take several days – or longer – but the process is hugely enjoyable, like trying to solve a difficult brain teaser. The funny thing is that often what seems relatively easy to translate, where the language itself is simple, might turn out to be the hardest thing because you want to avoid using a particular word (if it had been used before), or you want to keep the rhythm of the line nicely balanced and the literal translation won’t work. In the second line of poem I of “Las cigarras” (Cicadas), for example, the line reads: “las cigarras empiezan sus odas lentas” (literally: the cicadas begin their slow odes). There’s nothing complicated about the language here, and “the cicadas begin their slow odes” is acceptable in English except for the fact that I didn’t like the strong vocalic assonance of “slow odes”. If you say it aloud it sounds like you’re trying to say something with an egg in your mouth. I’m conscious of the phonic effect of words, so semantic exactitude doesn’t always satisfy my ear. The problem then is that there are so many synonyms of “slow”. It took me ages to finally settle for “unhurried odes”, which also reflects the lilting, languid rhythm of the original.

There are many references to Greek mythology in the collection, some of which I was familiar with, and some not. A quick online search can clarify that a kouros is a free-standing statue of a young boy, often a representation of Apollo, and while any reading of these poems is richer if you are familiar with the Greek references, from the point of view of translation, once I could find the English equivalent, lack of detailed knowledge about artefacts or gods was not a significant problem.

DB: Any crossover with your own work, similar themes or styles?

ACS: Not really. The work I translate is quite different in theme and style from my own work. That has happened by chance, but I’m not sure I’d like to translate someone’s poetry if it reminded me a lot of my own. It’s nice to take a break from the usual preoccupations and discover other ways of writing, images that would never have occurred to you because they’re very foreign or because they come from a discipline that you don’t often engage with. The process of discovery adds to the pleasure of translating.

DB: I’d love to know of any difficult translation decisions, if there were any for you, what were they, how did you go about resolving them?

ACS: The use of idioms often poses problems for the translator, of course, resulting in the classic case of something being lost in translation. There was one instance of that in this collection with the word “cántaros”, which are clay pitchers or jugs for water or wine. It appears as the title of one section in “The Wine of Things” and is also repeated in several poems in a general way. But it’s also used in the expression “A cántaros”, which means “cats and dogs”, as in “it’s raining cats and dogs”. Clearly, when it’s used in Spanish to mean “cats and dogs”, none of the generic English translations works. It’s a shame because it means that the repetition of the word throughout the entire section is slightly lost. Not only that, “cats and dogs” has a totally different connotation in English compared to the Spanish “cántaros”. Cántaros are receptacles, for a start. The fired earth they’re made from has some echoes of antiquity and domestic labour. In comparison, “cats and dogs” sounds completely trivial at best, and if we take the origin of the phrase to be related to Jonathan Swift’s “A Description of a City Shower”, where cats and dogs drown in the downpour and flow along the flooded streets, then it’s completely disgusting. Either way, it won’t work as a translation. Another option might be “pouring” or “pouring rain”, but you lose the image of the container. In the end, I opted for “Bucketing”, even though the tone is a bit colloquial.

That presented yet another problem. The cántaros of the title should ideally be the same word that is used in the poems. I had opted for “pitchers” as a generic translation, with “bucketing” when referring to rain, but I didn’t like either of these as a section title. I suppose I might have settled for pitchers and been forever dissatisfied with its ambiguity had I not mentioned the problem to Elsa. Her solution – to use the Greek word “kantharos” – seemed perfect. Not only does it encompass all versions of kantharos (jugs, pitchers, buckets), and is in keeping with the Greek setting of the entire collection, it slightly elevates the tone of the more common “cántaros”, making up to some extent for the fact that the idiom is lost in English.

The other translation difficulty that arose was in the Aeolides, Oceanides, and Nictides sections. Here, the poems are of haiku-like brevity, often beginning with a verb conjugated in the third person plural (“they”). The subject is the daughters of the wind, sea or night, depending on the section in question. The fact that Spanish does not require the subject pronoun to be stated – because it is incorporated in the verb conjugation – allows for a profusion of lexical diversity in each poem. Here’s an example from “Eolides, 7”:

Despeinan

…………..al joven eucalipto

hacen caer sus resinas

……………………………..sobre los barandales

Zumban amorosas

como abejorros

………………….en el hueco de las cañas

Llenan la mirada de hormigas amarillas

……………………de la avispa

English, being a language that requires the use of the subject pronoun, would transform each of the verbs (Despeinan, hacen, Zumban, Llenan) into “They uncomb”, “they make”, “They buzz”, “They fill”. Repeating the subject pronoun in each line of such a short poem creates unpoetic monotony compared to the breezy freshness of the Spanish. Avoiding the subject pronoun so often – there are many of these poems in the collection! – was probably the single greatest challenge that required various different solutions. Sometimes I use the subject pronoun once at the beginning but don’t repeat it for the second verb, in the hope that it will be understood to be implied, or I use gerunds for subsequent verbs. That’s what I did in the above example (They uncomb, making, Buzzing, Swarming):

They uncomb

…………………….the young eucalyptus

making its resin drip

…………………….on the handrails

Buzzing, amorous

like bumblebees

…………………….in the hollow stalks of canes

Swarming our gaze with yellow ants

On other occasions I changed the word order and/or the grammatical function from active to passive so as not to begin a line with the subject.

Someten a su ritmo (They subject…)

………..las flores encrespadas

………..el lomo de los cerros

Todo lo vuelven piedra lisa (They turn everything…)

becomes

Rimpled flowers

and hilltops

………..are subjected to their rhythm

Turned by them to smooth stone

DB: What do you think of the poems? How would you describe the book to someone down the pub? Why should people read this book?

ACS: If you don’t know Elsa Cross’s poetry, this book is as good a place to start as any. It’s a bilingual edition, which is always useful for the reader. Cross is considered one of Mexico’s leading contemporary poets and has been praised by Octavio Paz for her interplay of complex thought and clarity of expression. In my opinion, this is the key element in her work. There’s a strong sense of the poet sitting still, absorbing her surroundings through the senses first of all – sound, sight and touch in particular – as if she were meditating, then very deliberately using these senses as a conduit to something deeper. Small details of nature, or of a Greek statue, have the potential to reveal something worth knowing, but the slightest sound or movement, even too much sunlight, can shatter any meaning that might be contained in the moment (“meaning becomes / an incongruous stroke, / a particle that marries with dust.” Stones, 4). The elusiveness of meaning marries with vivid imagery ever so delicately, even when the poet paradoxically finds the image devoid of meaning. Take, for example, the opening of poem 3 of “Cicadas”:

The night swings

on the call of owls hooting.

Flapping,

words heard in a dream

……………………………take flight

at the sound of the first cicada

now fitfully cutting

……………………the silence of dawn.

Words wanted

……………………beyond what they are—

yet when we try to grasp them

their flight is slowly undone

………………………………like ritual gestures.

They empty of image,

are no more than voice—

……………………gloomy alliterations

……………………in a lower key,

resonance,

……………………the sea’s craving for its creatures.

I love her exploration of the ambiguity of what is real and what isn’t; her allusions to Dionysian indulgence, for which the poet clearly has a preference (“The only instrument is passion”, Cicadas, 4), counter-balanced by Apollonian ideals that are harder for humans to achieve (“You light up everything, / but who sees your shadow?” Offerings, “Paean”); the mysterious absence on occasion of a figure that seems to be central to the poet (“a presence not present”), whose footsteps she follows only to find that they disappear “mid-step”.

The book itself is divided into two sections: Beyond the Sea, and The Wine of Things. In keeping with the Greek theme, the first section is a series of Odes, while The Wine of Things contains dithyrambs that read, among other things, as a contemporary homage to the gods. The multiple layers of striking images, connotation, mythology, and the contemplative quality of these poems makes them endlessly fresh and appealing against the soothing backdrop of the Aegean.

DB: Tell us about yourself and your own work, what you’re working on now and what’s next.

ACS: At the moment I’m going through literary labour, waiting for a few books to be published. A collection of poetry is due out any day with Shearsman and will probably be available by the time this article is in print. It’s called onwords and upwords, and is a collection in which I continue to tease out the technicalities and function of language, and play around with form. I want to find different modes of expression all the time, which is quite hard – for me, anyway.

There’s another collection pending publication that was written with actress and poet Nina Karacosta where we challenge each other on a phonic level, with words in Irish (for Nina) and Greek (for me) to which we have to apply some kind of meaning in poetic form. That was a fun project, partly because we worked very closely together, spending a few weeks of the year deep in discussion, bouncing ideas off each other, developing a pattern of work that suited that particular project.

I’ve had these two collections in the pipeline for a while, along with Elsa’s book, and have found that I can’t think about the next project until I have these out of the way, so I haven’t done much writing recently. But I do have an idea up my sleeve which I might try to work on if I get some time. It should be a move away from poetry, though hopefully it will have poetic elements and, at the very least, I’d like it to be uncategorizable as a genre. I might approach it differently to my usual way of working. I work freelance, so my day is not dictated too much by a routine. I can usually write whenever I feel the need. One thing, though, I hate long hand! I hate the visual mess of text scribbled out, arrows pointing to afterthoughts, not being able to make out my own handwriting the next day… The pc ensures I always have a clean text in front of me. I edit and re-edit every line as I go along so that by the time I’ve written the last line, the poem is pretty much as I want it. I rarely make changes afterwards.

With poetry, I never have an overall vision for a book when I start. I write in response to some unconscious need to address individual issues, although in the process of writing, the form can take precedence over the substance. That’s what I discovered was the unifying element in onwords and upwords – hence the title. However, for the next project, I have a better sense of where it might lead. The reason for that is that, unlike with poetry collections, I have a theme in mind for this next experiment. I’ll put a few ideas together during the summer, a general skeleton. If it has decent limbs and a backbone I might try and flesh it out.

Another project I have to tick off the to-do list is a novel I wrote many years ago. It’s called The Big e, and has been fully edited and ready for publication for a while, very frivolous and fun, and unlikely to have a sequel or to appeal to publishers, so I’ll self-publish it at some point. With that, I was pretty structured in how I wrote, trying to get something on paper every day, usually in the morning. The fact that the writing went on for about three years didn’t really appeal to me, even though it’s fun to live in the parallel universe of your characters for extended periods and see things through their eyes. Overall, I prefer brevity, even when translating. I’ve translated a few novels and have found that the process becomes a bit tedious half way through because you still have another 150 pages left and will have to spend another few months with the same characters.

For translations I have a deadline that I stick to very rigorously. With poetry it’s always a generous deadline because poets and publishers of poetry understand the need for time to allow a text to settle (not so in the case of novels where there are commercial demands that don’t apply to poetry). I work methodically, setting aside the time I will need for a first draft, followed by a few weeks where I put the translation aside and forget about it so as to come to it from a fresh perspective for a full edit. During the first draft I put together whatever queries I have for the poet, incorporating the answers when they come back so that after the full edit I can send the manuscript to the poet for an overview. There are always more queries and comments at that stage. I go through several complete edits before the manuscript is ready for the publisher, and when it comes back for proofing I make additional final changes. Even after publication I wish I could make more changes. The process is never finished for me. I’m rarely fully satisfied with the result but have come to accept that a translation can only be the result of the translator’s reading of the original text at one particular moment in time. Tomorrow, the translator’s world view and state of mind and experience of language will have shifted ever so slightly.

§

Selections from Beyond the Sea, by Elsa Cross, translated from the Spanish by Anamaría Crowe Serrano.

From Beyond the Sea

WAVES

1

Your face appears.

Sinks into milk,

like the well-begotten Lamb

………………………………………….in the Mysteries.

The fire approaches without touching us.

Blue more intense

than the elation building towards the islands.

Trembling,

as if behind smoke,

…………………………………your face appears.

The conch mixes the sea

with wonder itself

…………………………………in our ear,

waves surging

………….where the mind’s islands navigate,

flashes—

……………………Beyond the sea.

Movements of thigh and hip

tentatively outline

……………………………….a dance.

…………..The sea stretches

…………………………………in unbreaking waves.

Movement—

the last vowel

……………………….reverberates in the ear.

…………..The sea stretches

…………..beyond time

…………..…………..immovable.

A tremble,

…………..…………..an echo of movement—

hushes

and speaks to us

…………..…………..in its other tongue,

like that fire burning within,plays and spreads

until it quietens in a vertical ray.

Omnipresent,

…………..…………..the language of touch without hands.

.

4

A manly sound, that language of the islands.

Strong syllables,

…………..…………..honed vowels

like colours separating the sea from the crags.

Island emerging from nowhere,

place where no one is born

…………..…………..…………..or dies.

Only the course of its ground is followed,

piling its broken signs

…………..…………..…………..…………..on the grass—

stelae

unfold their argument on the waves,

…………..hold it,

…………..…………..bend it, withdraw it

…………..…………..—seduce the eye—

…………..…………..…………..…………..…………..repeat it.

The music of that tongue rises to the retentive ear,

and the ear stays open

…………..…………..…………..in its intoxication—

maybe it translates the tumble

…………..…………..of the wave rushing to die on the sands,

or the delight

…………..…………..of she who is born from the spray.

Is there anything that does not come from the sea?

Names that don’t attract death

…………..…………..…………..but maybe sweeten its arrival:

…………..…………..She of the Delectable Voice

…………..…………..She of Nascent Desire

…………..…………..She Bathed in Light—

…………..…………..…………..…………..She the Inevitable.

.

5

Silent women,

chiselled plaster on the wall

…………..…………..…………..—asymmetries.

From the crest of a moon

olive trees balance

…………..…………..…………..precariously

as evening declines.

Summer carts make their way up

…………..…………..…………..…………..to hillside houses,

and with the setting sun

a bright snake

…………..…………..—a bicycle lamp—

meanders through the vineyards.

Venus and the waning moon

…………..…………..…………..…………..in conjunction

light up the waters.

The island

copies the shape of that half-moon

bending its back

…………..…………..…………..between two ridges—

remains of its body float

…………..…………..…………..like charred bones.

Thus the sea of dreams joins or devours

fragments of the divided substance.

On the wing of an insect the fabrics of vision:

the city twinkles

…………..…………..through veils of plumbago,

over beaches almost blurred from view.

In enclosed courtyards

the light seems to rise from a hidden well;

desires gleam—

…………..…………..such is the accumulated transparency.

And the memory of a disaster.

Fragments of consciousness

emerge

…………..………….. and submerge

…………..like those islands.

.

CICADAS

5

Jellyfish lesions on skin,

as if each cicada

…………..…………..were stabbing with a hairclip

or armies of ants were leaving burning trails

…………..…………..…………..…………..…………..in their wake.

Pale skies as summer unfolds.

And all that light,

…………..…………..the whiteness of a marriage bed,

those terraces where the night slips in

on a silver thread,

…………..…………..inaudible strumming,

are all still there,

when we’ve been around

the crest of the new moon

…………..…………..…………..at one end of our heart.

And the sea—

at twilight it takes on

the colour of our golden wines.

The wineskins are empty.

The hour bites our temples,

disrupts

…………..the journeys;

what we gave and didn’t give each other

sparkles

…………..under the sun as it moves away.

No sea as blue,

no light

…………..as white,

even though that splendour

may already have held

…………..…………..…………..the caress of darkness.

.

From The Wine of Things

NICTIDES

9

They are repeated insomnia

a little sting

…………..………….. the flapping

of memories not sheltered

…………..…………..…………..by presence

.

10

They are a white shadow

innocence in the yellow phrases

…………..…………..…………..……….of a dying man

the catastrophe of the voice

.

11

They are vague emotions

…………..…………..…………..in the stillness of the day

hollow bells

mist crouching

…………..…………..in your chest

like a doubt

.

12

They are transversal signs

…………..…………..…………..withered tributes

fragments lifted from the debris

They are hidden diamonds

.

THE WINE-RED SEA

(On the Dionysus Kylix)

…………..…………..…………..…………..for Ursus

O waves so red,

confluent streams

…………..…………..where grapes and dolphins almost meet,

and the vertical mast,

now trunk and branches,

…………..…………..…………..spreads its arms east and west.

And the dolphins freely swim

…………..…………..…………..…………..—old sailors

guarding the vessel.

And the sail bulging white

…………..…………..…………..under lavish grapes,

and the graceful ram at the prow,

what beach are they pointing at?

where will they dock

…………..…………..…………..if the blissful god

neither charts the course nor guides

but merely sips

the pleasant breezes

…………..…………..and the scent of the wine-red sea?

—

§

—

De Ultramar

Las Olas

1

Aparece tu rostro.

Se hunde en leche,

como el Cordero bienhallado

…………..…………..…………..en los Misterios.

El fuego se acerca sin tocarnos.

El azul es más intenso

que la ebriedad creciendo hacia las islas.

Tembloroso,

como detrás de humo,

…………..…………..…………..aparece tu rostro.

El caracol mezcla el mar

al propio estupor

…………..…………..en el oído,

oleaje donde navegan

…………..islas de la conciencia,

destellos—

……………Ultramar.

Movimientos del muslo y la cadera

esbozan al tiento

…………..…………..una danza.

…………..El mar se extiende

…………..…………..en olas que no se rompen.

Movimiento—

la última vocal

…………..…………..reverbera en el oído.

…………..El mar se extiende

…………..más allá del tiempo,

…………..…………..…………..inamovible.

Temblor,

…………..…………..eco del movimiento—

calla

y nos habla

…………..en su lengua otra,

parecida a ese incendio de adentro,

juega y se difunde

hasta aquietarse en un rayo vertical.

Omnipresente,

…………….lenguaje del tacto sin manos.

…………..

4

Sonido varonil, ese lenguaje de las islas.

Sílabas contundentes,

…………..…………..vocales definidas

como colores que separan el mar de los peñascos.

Isla salida de la nada,

lugar donde no se nace

…………..…………..…………..ni se muere.

Sólo se sigue el decurso de su suelo,

que apila sobre la hierba

…………..…………..…………..sus signos rotos—

estelas

despliegan en la onda su argumento,

…………..…………..lo sostienen,

…………..…………..…………..lo curvan, lo sustraen

…………..…………..–seducen al ojo—

…………..…………..…………..…………..lo repiten.

La música de esa lengua sube al oído retentivo,

y el oído queda abierto

…………..…………..…….en su embriaguez–

quizá traduce el tumbo,

…………..de la que corre a morir en las arenas,

o el gozo

……………de la que nace de la espuma.

¿Qué cosa no viene del mar?

Nombres que no atraen a la muerte

…………..…………..…………..pero tal vez endulzan su llegada:

…………..La de Voz Deleitosa

…………..La que Despierta el Deseo

…………..La Bañada en Luz—

…………..…………..…………..…………..La Inevitable.

…………..

5

Mujeres taciturnas,

cinceladuras de yeso en la pared

…………..…………..…………..…………..–asimetrías.

Desde una cresta de luna

los olivos se equilibran

…………..…………..…………..precarios

en el declive de la tarde.

Suben las carretas del verano

…………..…………..………………hacia los caseríos altos,

y al ponerse el sol

una serpiente luminosa

…………..…………..…………..–fanal de bicicleta—

ondula en los viñedos.

Venus y la luna menguante

…………..…………..…………..…………..en conjunción

iluminan las aguas.

La isla

copia la forma de esa media luna

quebrando su espinazo

…………..…………..…………..entre dos puntas—

restos de su cuerpo flotan

…………..…………..como huesos calcinados.

Así el mar del sueño junta o devora

fragmentos de la sustancia dividida.

En un ala de insecto los tejidos de la visión:

la ciudad parpadea

…………..…………..en veladuras de plúmbago,

sobre playas que apenas se distinguen.

En los patios cerrados

la luz parece ascender de un pozo oculto;

brillan los deseos–

…………..…………..…………..tanta la transparencia acumulada.

Y una memoria de desastre.

Fragmentos de conciencia

emergen

…………..y se sumergen,

………..como esas islas.

…………..

LAS CIGARRAS

5

Huellas de medusas en la piel,

como si cada cigarra

…………..…………..punzara con una horquilla

o legiones de hormigas dejaran rastros quemantes

…………..…………..…………..…………..…………..de su paso.

Cielos pálidos al transcurrir el verano.

Y toda esa luz,

…………..…………..esa blancura de tálamo,

esas terrazas por donde entra la noche

en un filo plateado,

…………..……………..rasgueo inaudible,

siguen allí,

cuando hemos recorrido

la cresta de la nueva luna

…………..…………..……….en un extremo del corazón.

Y el mar—

toma al crepúsculo

el color de nuestros vinos dorados.

Los odres están vacíos.

El vino muerde ahora la sien,

trastorna

…………..las travesías;

lo que nos dimos y no nos dimos

brilla

…………bajo un sol que se aleja.

Ningún mar tan azul,

ninguna luz

…………..tan blanca,

aunque ese esplendor

ya llevara consigo

…………..…………..la caricia de lo oscuro.

…………..

De El vino de las cosas

NICTIDES

9.

Son insomnio repetido

un pequeño aguijón

…………..…………..………….. revoloteo

de recuerdos no amparados

…………..…………..…………..…………..en la presencia

…………..

10.

Son sombra blanca

la inocencia en las frases amarillas

…………..…………..…………..…………..del moribundo

la catástrofe de la voz

…………..

11.

Son emociones difusas

…………..……….en lo inmóvil del día

campanas huecas

niebla que se agazapa

…………..…………..en el pecho

como una duda.

…………..

12.

Son signos transversos

…………..…………..…………..homenajes marchitos

trozos levantados de los escombros

Son diamantes ocultos

…………..

EL MAR COLOR DE VINO

(Sobre el kílix de Exekías)

Para Ursus

Oh mar tan rojo,

corrientes encontradas

…………..…………..casi juntan racimos y delfines,

y el mástil vertical,

vuelto cepa y sarmientos,

…………..………..abre brazos a oriente y a poniente.

Y van a su albedrío los delfines

…………..…………..…………..………..viejos marinos

custodiando la nave.

Y la vela tan blanca que se abomba

…………..…………..…………..bajo las uvas pródigas

y el espolón gracioso de la proa

¿hacia qué playa apuntan?

¿en dónde atracarán si el dios

…………..…………..…………..……….dichoso

no marca ruta o guía

y solo bebe

los vientos placenteros

…………..…………y el aroma del mar color de vino?

— Elsa Cross, translated from the Spanish by Anamaría Crowe Serrano

.

.

Elsa Cross was born in Mexico City in 1946. The majority of her work has been published in the volume Espirales. Poemas escogidos 1965-1999 (UNAM, 2000), but a new complete edition of her poetry appeared in 2013 from the Fondo de Cultura Económica in Mexico City. Her book El diván de Antar (1990) was awarded the Premio Nacional de Poesía Aguascalientes (1989), and Moira (1993) won the Premio Internacional de Poesía Jaime Sabines (1992), both in Mexico. Jaguar (2002), is inspired by different symbols and places of ancient Mexico. Her more recent books form a trilogy: Los sueños — Elegías, Ultramar — Odas, and El vino de las cosas, Ditirambos.

Her poems have been translated into twelve languages and published in magazines and more than sixty anthologies in different countries. She has also published essays. She has a M.A. and PhD in Philosophy from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where she holds a professorship and teaches Philosophy of Religion and Comparative Mythology.

In 2008, Elsa Cross was awarded the most prestigious poetry prize in Mexico, the Xavier Villarrutia Prize, an award that she shared with Pura López-Colomé.

§

Anamaría Crowe Serrano is a poet, translator and teacher born in Ireland to an Irish father and a Spanish mother. She grew up bilingual, straddling cultures. Languages have always fascinated her to the extent that she has never stopped learning or improving her knowledge of them. She enjoys cross-cultural and cross-genre exchanges with artists and poets, the most recent of which is her participation in Robert Sheppard’s EUOIA project and her involvement in the Steven Fowler’s ‘Enemies’ project.

She has published extensively and her work has been widely anthologised in Ireland and abroad. Her publications include Mirabile Dictu (blurb, 2011), one columbus leap (corrupt press, 2011), and Paso Doble, written as a poetic dialogue with the Italian poet Annamaria Ferracosca (Empiria, 2006).

Anamaría has translated some fourteen books, including Elsa Cross’s Beyond the Sea for Shearsman Books.

.

![[Now, the storm has arranged the insane]](http://dgvcfaspring10.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/1-again1.jpg)