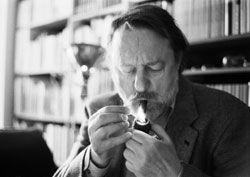

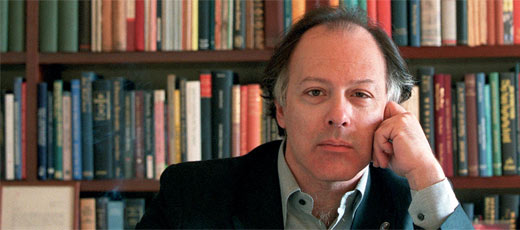

Bruce Stone pens here a stylish, exuberant review essay on the latest Thomas Pynchon novel Bleeding Edge. Phrases like “polymathic autism” and “swarming with goombas of paradox” are alone worth the price of admission (not to mention gorgeous encapsulations of Pynchon’s prose). But Stone, himself a literary polymath of sorts, brings all the weight of long reading and intelligent discernment to a serious and important analysis of the legendary American author.

dg

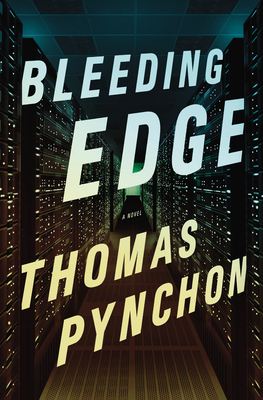

Bleeding Edge

By Thomas Pynchon

Penguin

477 pages; $28.95

.

Bleeding Edge, the new novel from Thomas Pynchon (yes, that Thomas Pynchon, our Thomas Pynchon), could prove to be his most saleable book to date. This is either an insult or a compliment, depending on your loyalties. The novel taps two deep and plasma-rich veins of contemporary culture: digital technologies and the “11 September” catastrophe. In the historical coincidence of the Internet’s accelerated rise and the Towers’ unthinkable fall, the book finds causality, elaborating a convoluted link between the two phenomena. Because this is Pynchon’s world, Bleeding Edge also encompasses Korean karaoke, progressive school curricula, classic video games, a recipe for Tongue Polonaise, Madoff ponzi schemes, designer Russian ice-cream, the continental drift of Manhattan’s urban landscape, the defunct playlist of WYNY, IKEA rage, time travel and much more. Conveniently, this compact encyclopedia of a book volunteers two apt phrases to describe its own agenda: it’s both a kiss-off “Valentine to New York” and, like the Deep Web interface that anchors the plot, a “dump, with structure.”

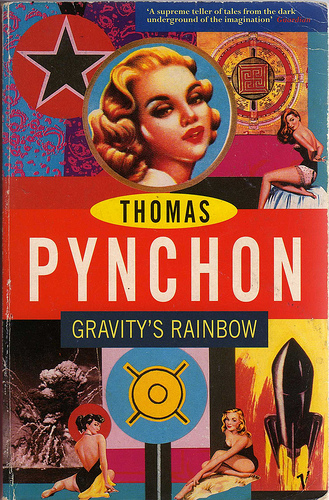

As a novel, Bleeding Edge is the work of a master yet in his prime, the Indian summer of a legendary career (at 76, Pynchon is still chronically hip); it’s funny, wise, handily plotted, unerring in its style, generally user-friendly and eminently readable. If anything, the book is a little conventional, almost pulpy: embarrassingly linear, with off-the-rack noir clichés and oodles of dialogue (albeit excellent dialogue) to carry the narrative along. What’s most surprising about Bleeding Edge is its fluency in classic novelistic techniques: it features an artful density in its character portraits, a subtly echoing plot. That is to say, Gravity’s Rainbow it ain’t. However, if you can imagine that magnum opus narrated, or shot, from a single stationary tripod, manned by a competent and sane operator, with turn-of-this-century America for a backdrop, you might get something like Bleeding Edge. If the work disappoints somewhat as art, it remains a welcome—no, a priceless—addition to the Pynchonian catalogue and to the archeological record of Western letters: the book is a chemical peel for the face of the modern nation, a tactical assault on some cherished cultural pieties.

Set among the pan-ethnic precincts of millennial Manhattan, the novel chronicles the events—both the domestic day-to-day of the protagonist and the international intrigue of the dot-com bad guys—surrounding the 9/11 attack, and the intention is to stoke, determinedly, those period rumors of US complicity in the event. The heroine is Maxine Tarnow, a private fraud investigator, recently decertified by the fraud-investigator certification board (apparently such a profession exists), and the whole novel fits in her hip pocket as she chases down an array of bookkeeping irregularities that lead her straight into the heart of the Deep Web and its corollary 9/11 conspiracy theory. If, like me, you have no idea of what the Deep Web is, the novel offers an erratic user’s guide: the term refers to a layer of cyberspace invisible to web crawlers and search engines, a repository of sites criminal and goofy, unfit for public consumption, as well as a junkyard of surface-web offerings that have expired from “linkrot.” Applications in this domain can be accessed by invitation only, with a special passkey. For this sub-hyperspatial dimension, Justin McElmo and his partner Lucas, California transplants, have built a platform called DeepArcher (a pun on departure) with a diabolical security design that makes it untraceable and unhackable, script features that are especially attractive to Web-giants and poachers (think, Microsoft and the US government). In this case, the code is more interesting than the content because DeepArcher appears to be a kind of SecondLife for cultural dropouts, those surfers who plug in with the sole purpose of vanishing from the grid (it’s ironic).

Maxine logs a lot of hours at the keyboard, “dowsing” this cyber-landscape, clicking on its nested links, and the time isn’t entirely misspent. Some of the novel’s most artful lines arise in the act of evoking screenscapes:

The screen begins to shimmer and she is abruptly, you could say roughly, taken into a region of permanent dusk, outer-urban somehow, … underpopulated streets increasingly unlit, as if public lamps are being allowed to burn out one by one and the realm of night to be restored by attrition. Above these somber streets, impossibly fractal towers feel their way like forest growth toward light that reaches this level only indirectly….

What’s more, the virtual world courses with the book’s thematic energy, its peculiar mysticism, its antagonism of capitalist economics, its potential to steer actual human destinies, and even its promise to sustain a digital afterlife for the departed. The biggest thug in the scrum surrounding DeepArcher is Gabriel Ice, impresario of a computer-security company named, with an improbable pun, hashslingrz. Like most of the novel’s men—from Bernie Madoff (offstage) to Vip Epperdew, a peripheral point-of-sale fraudster—Ice is a crook, embezzling funds from his company through the undecryptable back alleys of the Deep Web: he might also be funneling money to the Middle East, financing the terrorist attack with the government in cohoots. But readers should notice how carefully Ice’s biography echoes that of Nicholas Windust, the novel’s ersatz-Rocketman figure, a black-ops agent who is either abetting or hampering Maxine’s investigation. Both men start out with clear eyes and fresh faces—Ice in the computer sciences, Windust with a nonspecific government agency—yet time and experience corrupt both men irreparably: fully fledged, they both engage in pseudo-sadistic sex practices, and both appear to have blood on their hands (in roughly similar quantities).

These harmonic character portraits are, in fact, typical, almost ubiquitous, in the novel, with its populace of male embezzlers and female adulterers (Ice’s wife, Tallis, nicely synthesizes these gender-skewing malfeasances). Of the latter faction, one dramatic example is Maxine’s long-time friend, the City College professor Heidi Czornak, who has overlapping affairs with Carmine Nozzoli, a cop with a hard-on for petty street crime, and Conkling Speedwell, a “professional nose” (someone with superheroic olfactory senses) who helps Maxine sniff out criminals; she also admits to some more distant hanky-panky with Maxine’s estranged day-trader husband, Horst. Of the men, besides the likes of Vip Epperdew and the Russian mobster Igor Dashkov, Lester Traipse also engages in Icy behavior, having the gumption to siphon money out of hashslingrz’s Deep Web accounts. These lists go on, and while this is old-school novelistic artifice, here Pynchon seems to exacerbate the technique, which might contribute to the book’s big-picture obscurity: it becomes a little hard to keep straight who’s doing what when everyone’s up to the same narrow range of no good. Even so, by Pynchon’s standards, Bleeding Edge is a breeze: call it beach-reading with fangs.

Along with the combustible subject matter, what most recommends Bleeding Edge to a wide audience is its impeccable style. Pynchon’s facility with language is unrivalled—he’s an expert voice imitator, but in the new book, rather than pillage the history of literary manners, he plies this talent only to render the idiosyncratic voices of his characters. As a rule, the prose in Bleeding Edge has a studied laxity, a colloquial inflection; of these playfully virtuosic sentences, most channel the cluttered, wise-cracking speech, wry and hardboiled, of his Jewish-mother protagonist. Pynchon shows a special taste for vexed syntax, a kind of deadpan convolution, in the book; see this description of Tallis Ice:

Black silk slacks and a matching top unbuttoned halfway down, which Maxine thinks she recognizes from the Narciso Rodríguez spring collection, Italian shoes that only once a year are found on sale at prices humans can afford—some humans—emerald earrings weighing in at a half carat each, Hermès watch, Art Deco ring of Golconda diamonds which every time she passes through the sunlight coming in the window flares into a nearly blinding white, like a superheroine’s magical flashbang for discombobulating the bad guys.

Against the glitz of the accessorizing, the syntax preserves a homespun feel, and in a similar spirit, Pynchon also stoops repeatedly to retread clichés, some of which are especially pungent with age: “Maxine approaches the address from the other side of the street, and as soon as she catches sight of it, her heart, if it does not sink exactly, at least cringes more tightly into the one-person submarine necessary for cruising the sinister and labyrinthine sewers of greed that run beneath all real-estate dealings in this town.” This might be a dubious practice if the results weren’t so routinely excellent, and besides, the novel is, in certain lights, a cultural salvage yard, so we might as well spruce up the place with some recycling.

Over all, this is Pynchon at his most companionable and readable, and yet, there’s a steady brilliance luminescing in the prose, which occasionally flares up into bravura genius. In one of the novel’s best set-pieces, Pynchon offers this description of an actual island garbage dump, with a bird sanctuary cordoned off in its middle: “Neglected little creeks, strangely luminous canyon walls of garbage, smells of methane, death and decay, chemicals unpronounceable as the names of God.” The place evokes comparison with DeepArcher: “This little island reminds her of something, and it takes her a minute to see what. As if you could reach into the looming and prophetic landfill, that perfect negative of the city in its seething foul incoherence, and find a set of invisible links to click on and be crossfaded at last to unexpected refuge, a piece of the ancient estuary exempt from what happened, what has gone on happening, to the rest of it.” Perhaps the most breathtaking passage of the novel arrives later, as a “Geek Cotillion” breaks up, on the night of September 8; as partygoers head for the exits, one metastatic sentence lightly captures the spirit of the dot-com bubble while throbbing with the awful burden of foreknowledge:

Faces already under silent assault, as if by something ahead, some Y2K of the work-week that no one is quite imagining, the crowds drifting slowly out into the little legendary streets, the highs beginning to dissipate, out into the casting-off of veils before the luminosities of dawn, a sea of T-shirts nobody’s reading, a clamor of messages nobody’s getting, as if it’s the true text history of nights in [Silicon] Alley, outcries to be attended to and not be lost, the 3:00 AM kozmo deliveries to code sessions and all-night shredding parties, the bedfellows who came and went, the bands in the clubs, the songs whose hooks still wait to ambush an idle hour, the day jobs with meetings about meetings and bosses without clue, the unreal strings of zeros, the business models changing one minute to the next, the start-up parties every night of the week and more on Thursdays than you could keep track of, which of these faces so claimed by the time […]—which of them can see ahead, among the microclimates of binary, tracking earthwide everywhere through dark fiber and twisted pairs and nowadays wirelessly through spaces private and public, anywhere among cybersweatshop needles flashing and never still, in that unquiet vastly stitched and unstitched tapestry they have all at some time sat growing crippled in the service of—to the shape of the day imminent, a procedure waiting execution, about to be revealed, a search result with no instructions on how to look for it?

The book can be majestic when it peers into the near future or the not-so distant past, but usually, as it roots through the gutters of the fictional now, its beauty is matter-of-fact: consider this description of Ground Zero: “They’re up on the bridge again, as close to free as the city ever allows you to be, between conditions, an edged wind off the harbor announcing something dark now hovering out over Jersey, not the night, not yet, something else, on the way in, being drawn as if by the vacuum in real-estate history where the Trade Center used to stand, bringing optical tricks, sorrowful light.” If the tone sometimes edges into an apocalyptic gravitas, comedy is never very far away either: to describe a phenomenon that the book calls “virtuality creep,” minor ruptures in spacetime as “DeepArcher … overflow[s] out into the perilous gulf between screen and face,” Pynchon writes, “Out of the ashes and oxidation of this postmagical winter, counterfactual elements have started popping up like li’l goombas.” A pidgin contraction has never before made me want to throw my arms in gratitude around a writer, but this one does.

As the antic style suggests, for all its catastrophic events and big-ticket conflicts, Pynchon’s novel is scrupulously unsentimental; it draws what little emotional heft it has from the agonies of 9/11, evoking these deftly, often by indirection and understatement. One of the rarest feats of Bleeding Edge is that it renders a strange hiccup in stock-trading activity that will cause you to catch your breath. In the same vein, one of the most haunting passages is an inconspicuous moment, a mere paragraph, in which Horst, shortly before the 9/11 attack, lightheartedly translates the term Inshallah, as spoken by a Muslim cab driver: “‘Arabic for “whatever,”’ Horst nods. They’re waiting at a light. ‘If it is God’s will,’ the driver corrects him, half turning in his seat so that Maxine happens to be looking him in the face. What she sees there will keep her from getting to sleep right away. Or that’s how she’ll remember it.” This tendency toward attenuation emerges radically in the depiction of the event itself, which arrives about two-thirds of the way into the book; the attack is viewed only on television, almost casually glossed in two scant sentences: “Maxine goes home and pops on CNN. And there it all is. Bad turns to worse.” But this just goes to show that Pynchon’s interest lies in the matrix surrounding the event, rather than the epicenter itself. And the book might miff a few readers as it punctures the patriotic illusions that sprouted from the ruins of the Towers. Bearing the brunt of the abuse is the NYPD, whose officers, per Bleeding Edge, menacingly brandish their mantles of heroism. Also, the real-estate wolfpack gets its comeuppance for crimes past and present: they not only rapaciously churn under Manhattan’s urban identity in a death march to a capitalist dystopia, they also start wrangling immediately, even as the rubble smolders, for the rights to profit from this sudden cavity in the downtown realty market. The book reserves a special venom for Republican politics, which it implicates in the terrorist attack for the usual reasons (to keep us scared, etc., maybe also to herd us online), but Democratic standard-bearers aren’t spared either. One of the book’s heroes is a crusader of the far-left named March Kelleher, but her virtue lies precisely in her distance from the capitalist position trumpeted in the Newspaper of Record, as the book contemptuously refers to the Times.

The targets here are clear, yet the book’s plot still feels diffuse. Like many Pynchon novels, this one has a stately sprawl: he seems to construct a narrative centrifuge that holds a Byzantine myriad of bright shards in orbit, but ultimately succumbs to entropy, tapering off rather than converging climactically. That is, we get a lot of Windust in our eyes, but nothing in the kaleidoscope really comes into sharp focus. The novel breeds new characters as a matter of convenience (including an oracular bike messenger) to carve fresh turns in the labyrinth, and the narrative shuttles rather abruptly between its bipolar storylines: the homely arena in which Maxine tends to her family and friends and the pot-boiling Web-thriller action. At times, these segues veer into the implausible. When Maxine, in the course of her sleuthing, stages an amateur performance at a strip club—a set-piece that concludes with her gifting a footjob to the code-geek Eric Outfield—the action feels flimsy psychodramatically.

A few other red herrings surface in the plot: for example, the 9/11 conspiracy includes a dubious Plan B, involving rooftop operatives with surface-to-air missiles, to ensure the mission’s completion. However, the strangest glitch in the narrative fabric arrives when Maxine breaks into Ice’s Montauk hideaway and discovers a secret passage giving on to an eerie lair, a government laboratory with shades of alien encounters and time travel. It’s not entirely clear why Ice’s mansion would be the designated site for this government-sponsored creepiness, but in any event, the threat dissipates with cartoonish ease as Maxine puts her Air Jordans to work. The strangest thing, to my mind, about the episode is that the book seems self-aware of this cranial soft spot. In the wake of the 9/11 attack, the city’s residents, we learn, have been “infantilized,” and characters report encounters with weirdly childlike adults, figured in the novel as a variant of time travel. Elsewhere, the book reminds us that irony was another casualty of the 9/11 event: “Everything has to be literal now,” one flummoxed character gripes. The book appears to tease readers persistently with this interplay between the literal and the figurative: maybe the Montauk incident wants to be read as a literal translation of the metaphorical changes experienced by the populace. As such, the chapter might be dubious by design, a means of making transparent, or aggravating, this alteration between irony’s twin poles. That is, if the figurative infantilization of the city is irrational and scary, so is its literal corollary.

Here, we start to see the book’s carefully counterpointed plot construction, which, though subliminal amid the tsunami surge of the narrative, is almost Shakespearean in its precision. Early in the book, those small-time point-of-sale crooks have gadgets that allow them to both dip into unsuspecting tills AND to neutralize such invasive technologies: the same guys play both economic ends—demand and supply, crime and security—against the patsy of the middle. Later, the Deep Web plotline also hinges crucially on the manufacture and use of vircators, devices that similarly disable machinery through electromagnetic bursts. On a smaller scale, the novel evokes the pop-cultural cliché of rival East and West Coast rappers; the same bicoastal rivalry informs the portrait of the tech-sector gurus. More pointedly, the devastating collapse of the Twin Towers also has its miniaturized antecedent: the reported destruction of a pair of “colossal” Buddhist statues in Afghanistan. We find calculated artifice underlying even the worst of the novel’s mayhem.

Maybe the most resonant of these correspondences emerges when Maxine’s kids beta-test a jokey FPS videogame for the Deep Web, designed by Justin and Lucas as an offshoot of DeepArcher: the gameplay requires the kids to punish, vigilante-style, typical New York obnoxious behavior: shoppers illicitly grazing on supermarket produce, parents abusively reprimanding children, etc. Surprisingly, the novel’s plot appears to replicate the experience of the game: on the Thanksgiving following 9/11, as Maxine stands in line, waiting to purchase the bird for her main course, an aggressive patron, cutting his way viciously to the front, is felled by a frozen turkey lobbed in from the wings. In touches like this, the book suggests some link between the experience of the Deep Web and that of reading this novel, as if truly “the Internet is only a small part of a much vaster integrated continuum” that spans the poles of cyberspace and “meatspace.” This existential permeability works the other way, too, as some intrepid explorers of the Deep Web actively seek out a mystical “horizon between coded and codeless.” It’s hard to say if this is simply a proposition that the novel floats without leading to some rational terminus, or if it’s another teasing iteration of those phase-shifts between the literal and the figurative, or if in fact, there is something urgent and apprehensible to be drawn from the pattern (could it be all three at once?).

In any case, this convergence of Deep Web and Bleeding Edge begins to blunt some of the otherwise devastating critique of the Digital Age in its infancy (with proleptic nods to its current adolescence). Through the tech-savvy cast of characters, Pynchon skewers both the Net’s capitalist designers and its end-users almost equally. Reg Despard, the filmmaker who initiates Maxine’s investigation of hashslingrz, has a distinctive non-narrative, mindlessly-point-and-shoot aesthetic, which he sums up as a self-deprecating prophecy: “someday, more bandwidth, more video files up on the Internet, everybody’ll be shootin everything, way too much to look at, nothin will mean shit.” Later, the same proliferating trend is glossed more sumptuously: “The Internet has erupted into a Mardi Gras for paranoids and trolls, a pandemonium of commentary there may not be time in the projected age of the universe to read all the way through, even with deletions for violating protocol.” Maxine’s father, Ernie, gets the final word on the subject when the two debate the Net’s cultural potential: “It was conceived in sin, the worst possible. As it kept growing, it never stopped carrying in its heart a bitter-cold death wish for the planet.” Ernie also seems to anticipate the NSA’s Big-Brother machinations presently making headlines; however, all of this incendiary commentary founders when the book suggests that it is itself an analogue of DeepArcher and its offshoots. Is the book dramatizing the coercive power of the Internet, or does it betray, in a self-negating turn, its kinship with those pernicious virtual worlds? The latter seems more likely. Against the retail cacophony of advertising and masturbation that is the surface web (which houses some pretty fine magazines and blogs, as well), the Deep Web is, at least initially, in the hands of Justin and Lucas, an idealistic enterprise, a push for some antidote to the murderous virus of the US economy. And maybe this is what Pynchon has in mind with regard to his own novel: it too is an anarchistic affront to the status quo, but maybe, like DeepArcher, it is inescapably mired in the very economic forces that it attacks.

The current of nostalgia that courses throughout the book is also likely to dull the impact of the counter-cultural rabble-rousing. Bleeding Edge features occasional montages that seem to eulogize the comparatively innocent era of Times-Square peepshows and video arcades where kids once plugged quarters into the cabinet consoles of Galaga and Robotron 2084. Web apologists and urban planners might jeer at this as a dated technological conservatism, but one thing the book isn’t is naïve. Against an endemic pessimism and paranoia, the book does, however, hint at a few imperiled stays; in the end, it suggests that there might be at least one last sanctuary for nesting birds available, a safe harbor for citizens of the twenty-first century.

Pynchon’s work has long been notorious for its polymathic autism, its astounding range of erudition but its bumbling trade in human emotion. However, Bleeding Edge reveals a clear affection for its scrappier cast members, and Pynchon records convincingly the freezes and the melts in familial relations. The book warmly portrays the resurrected affection between Maxine and Horst, and as the plot trips along, we’re led to worry about their respective well-beings, but just a little. Maybe Pynchon’s appetite for, and startling ability to retain, cultural trivia tends to suppress the naturalistic heat of the characters’ relationships. There might even be a thematic upshot to these off-kilter balances between private desires and public detritus, as if identities are both saturated and dwarfed by the culture that houses them. My sense, however, is that these artistic cross-currents are Whitmanian in origin, reflecting the limitless fecundity of Pynchon’s imagination. (While this talent allows him to write metaphors that seemingly storm off into other novels, I wouldn’t mind if the book’s Ace Ventura reference, for example, fell victim to linkrot.) That is, the debris-collecting flair might not motivate the character portraits; instead, maybe the character portraits help to catalyze the wash of period details. The cast in Bleeding Edge is rigorously, even myopically, sketched, fully alive and breathing. Consider this little vignette of a tag-team Russian goon squad, distracted by Game Boys as they ineptly proctor an investigative tete-a-tete:

For a while, Maxine has been aware of peripheral armwaving and hand jive, not to mention quiet declamation and deejay sound effects, from the direction of Misha and Grisha, who turn out be great fans of the semiunderground Russian hip-hop scene, in particular a pint-size Russian Rastafarian rap star named Detsl—having committed to memory his first two albums, Misha doing the music and beatboxing, Grisha the lyric, unless she has switched them around.

Amid the roiling of world events, the minor dramas of these characters, their peculiarity and quiddity, their loves and triumphs, seem soft-pedaled, muted, whittled down to flashes of tenderness. But it’s here, at home, where a select few characters manage to bypass the socioeconomic matrix of criminal capitalism and mercenary sex, ultimately hinting at the book’s moral center. It’s a surprisingly domestic, even conventional space, but the novel insists that we hearken to it. As the book cycles to its close, these family affairs come to the foreground, eclipsing the convulsions of global terrorism. The dramatic switchback recalls the epilogue to War and Peace: against the marital relations of Pierre and Natasha, Napoleon is just a dissolving memory.

Of the many things that add some (bleeding) edge to this fuzzy familial warmth is that most of these characters, the surviving good-guys, possess a kind of ESP, a talent that leads the novel’s vision beyond the mundane. Maxine routinely exercises her intuitional second-sight when she detects, unaided, the lies and evasions of her suspects (even her bladder is a sensory detector of this type). Horst also uses his idiot-savant instincts to strike it rich in the market and avert disasters. The two share this ability with one of Speedwell’s colleagues, a “proösmic” nose, who can foretell catastrophes: after an olfactory premonition, she abandons Manhattan late in the summer of 2001. The novel appears to honor ratiocination and scrupulous domestic bookkeeping, but it lays down a healthy wager, as well, on the side of the supra-rational. Moreover, notice again how Horst blandly exercises the same preternatural ability as that clairvoyant nose: Bleeding Edge continually crosswires its twinned narrative poles, as if maybe all along a closer artistic correlation binds the private comedies and the public tragedies. The book doesn’t argue for a moral equivalence between domestic misdemeanors and terrorist atrocities, between the family tree and the body politic, but it does force us to view these loci and their transgressions on a behavioral continuum. In our last glimpse of Ice, we see him as just another rabid ex-husband-to-be, hell-bent on custody-battle payback: a strange curtain call for a supervillain, but there it is.

In the end, the book might be a Mobius strip, more artistic Easter egg than ideological hand-grenade. Maybe the digital-doomsday prophesies, the 9/11 conspiracy mongering, and much else besides are driven and subsumed by an aesthetic necessity, the book an involute web of sound and fury, ultimately signifying nothing. If this sounds like writerly passive-aggression, it helps to remember that art has always been so, going back at least to the Grecian urns memorialized by Keats. Some readers might accuse Pynchon of bad taste in bending such high-stakes material to his novelistic purpose, but I take the opposite view: I can’t shake the feeling that, in the novel’s evasive and ultimately peaceable vision, as the characters roll with the world-historical punches and reclaim their ordinary lives, Pynchon has missed an opportunity to etch some harsher, less delible mark on the national psyche. The book’s conspiracy theories, its demonization of dot-com capitalism, feel like the whirrings of a historical novel, a little feeble, an accurate snapshot of what was (and is) rather than some more revolutionary glimpse of what might be.

Even under these vitiated conditions, swarming with goombas of paradox, Bleeding Edge still offers one handy brick to hurl at the heads of thick-skulled Republicans, hypocritical Democrats and tech-sector pollyannas alike. As the book calls bullshit in the face of the collective storytelling enterprise that is our civilization, it manages to deliver a serious wallop before retreating, almost reluctantly, into its artful silence. (Above, behind, or below everything else, the loathing for “post-late capitalism” sticks, even if it grades, by force, into self-loathing.) And if the narrative surface is a little slushy and porous, the deep structure is taut, intricate and humming with voltage. Such a performance suggests that Pynchon has, to this point, staved off the decline that often befalls writers in their autumn years. Instead, he seems to be morphing (agreeably, for some, churlishly, for others) into your average marketable novelist with closet-virtuoso skills. But just as the book imagines a future in which cybergeeks might topple the capitalist forces of the Web, maybe we too can hold out hope for even greater things from this one-man panopticon and his omnidextrous English. If nothing else, Bleeding Edge will surely boost Pynchon’s notoriety for twenty-first century readers. But who knows, maybe it will prove to be a gateway to harder stuff, all around.

— Bruce Stone

,

Bruce Stone is a Wisconsin native and graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts (MFA, 2002). In 2004, he served as the contributing editor for a good book on DG’s fiction, The Art of Desire (Oberon Press). His essays have appeared in Miranda, Nabokov Studies, Review of Contemporary Fiction and Salon. His fiction has appeared most recently in Straylight and Numéro Cinq. He’s currently teaching writing at UCLA.

.

.