Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast

by Megan Marshall

365 pages; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; $30

.

Elizabeth Bishop is a poet whose work during her own lifetime failed to reach as wide a readership as her more celebrated contemporaries. She published relatively few poems – approximately one hundred poems constitute her entire body of work. Since her death in 1979, however, Bishop’s reputation and readership have grown exponentially; she is now considered by many critics to be one the best American poets of the 20th century.

Many of her poems were considered masterpieces by her contemporaries. They are full of formal intelligence, clear and elegant language and charm. But they exhibit a complicated emotional distance and reserve; her work stood in direct contrast to the more popular work of confessional poets like Anne Sexton and Adrienne Rich who dominated American poetry in the last two decades of Bishop’s life. A famously private individual, she held information about her life and emotions close to the chest, even with good friends. Her books were few and far between. And living abroad for many years, she kept herself apart from the turbulent cultural shifts of the mid-1960’s. Readers heard little from or about her.

The renewed interest and celebration of Bishop’s work might be partially due to the discovery of letters made public in 2015, written by the poet to her psychiatrist and friend, Ruth Foster. In them, we learn much more about her early traumas and frustrations, her sense of abandonment, her experience with incest and physical abuse, her long struggle with alcoholism, and her consistent belief that poetry provided the one stabilizing force in her life. The satisfaction poetry gave her was more reliable, even, than love. Near the end of her life, she had this to say about her work:

“What one seems to want in art is the same thing that is necessary for its creation, a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration. (In this sense it is always ‘escape,’ don’t you think?)”

Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast, Megan Marshall’s much-anticipated new biography of Bishop, limns not only the poet’s work for insights about what made her tick but also the more confessional mode with her psychiatrist. Those letters, quoted from extensively by Marshall, help readers understand Bishop’s sense that she was an “outsider” among the privileged class of people who surrounded her. The biographer, who studied briefly with Bishop at Harvard, also uses her training in poetry to unpack many of the allusions in the poet’s work. With both of those perspectives – confessional and professional – the emotional core of Bishop’s poetry becomes even more powerful and accessible.

A father dead when she was eight months old; a mother institutionalized for mental illness when Bishop was just five; removal from a well-loved home in Nova Scotia; incest involving a paternal uncle; life among a privileged class of people with whom Bishop felt ill at ease: Is it any wonder the poet kept some of these insecurities and traumas hidden? Is it any surprise she searched for a “life preserver” that could help her survive her addictions as well as the string of broken relationships she had with her lovers?

Bishop began to write poetry after an exclusive prep-school upbringing and entrance to Vassar. She was very much influenced by Marianne Moore, to whom she was introduced by a Vassar librarian. Bishop admired Moore’s technical mastery and ability to write directly from experience without sentimentality. In “Efforts of Affection: A Memoir of Marianne Moore,” Bishop said that Moore’s book Observations was “the self portrait of a mind…not as a model, and not as beauty, but as experience.” Moore urged Bishop not to submit poetry for publication until it was absolutely ready to send in, or “not at all.” Bishop followed that advice throughout her life, leaving many fine, unpublished poems among her papers. Her desire for perfection comes across in the biography as almost pathological.

As important as Moore was to Bishop, it was the poet Robert Lowell who played one of the most important roles in Bishop’s life. They became fast friends after being introduced by the another poet, Randall Jarrell; Lowell was “well-positioned” to connect her with other influential poets, many of whom offered lovely places to stay and sometimes funds to go with them. It was Lowell who named Bishop to succeed him as Poet Laureate (at the time called Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress) when she was only thirty-eight years old and had published only one book. It was Lowell who “nudged” people at Harvard to hire her when she finally did need a job, and it was Lowell who “wangled” grant money for her from a series of organizations including the Rockefeller Foundation. He also brought her to the attention of another well-connected person, Howard Moss, poetry editor of the New Yorker, to whom Bishop sent most of her poems as she finished them.

Elizabeth Bishop with Robert Lowell on the beach in Brazil, 1962

Elizabeth Bishop with Robert Lowell on the beach in Brazil, 1962

Lowell was authentic in his admiration; he carried a copy of Bishop’s poem “The Armadillo” in his wallet for years. Granted, Bishop’s work was excellent, but what might have become of her without these Good-Old-Boy connections? The list of them is long. A small trust fund from the Bishop estate to “cover rent and necessities” helped her survive for years as a non-teaching poet. But, truth be told, she depended on the loving, patient, and sometimes indulgent support (economic as well as emotional) of many friends and long-term lovers.

Marshall does a fine job of explaining Bishop’s desire not to go public with her sexual orientation. The atmosphere of tension and persecution in the United States during McCarthyism – attacking communists and “perverts” during the straight-laced 1950’s – was intense; Bishop felt no need to have her homosexuality be a factor for people reading her work. Perhaps she avoided teaching in the 50’s and 60’s because she knew what kind of price would be paid if her sexual preferences became public.

Her long-term relationship with a Brazilian landscape designer and architect named Lota Macedo de Soares (described by Wikipedia as “well connected” – a phrase which comes to mind so often in the reading of this biography) began to fail in the late 60’s. But Bishop still preferred not to align herself with “women poets,” believing the phrase to be demeaning. She refused to let her poems be published in anthologies which contained only work by women. She did not admit her lesbianism even when social tensions dissipated and persecution was becoming a thing of the past.

In a letter to her psychiatrist Bishop once wrote that when she was young, “I got to thinking that they [men] were all selfish and inconsiderate and would hurt you if you gave them a chance.” But she never went public with that feeling, and she was no feminist. In fact, she was apolitical, describing the Watergate hearings on the “god damn TV” during the summer of 1973 by saying, “If this is witnessing history – I’d rather not.”

Bishop’s 16-year relationship with Macedo de Soares was the longest sexual relationship of her life, a life sprinkled with love affairs before, during and after that time period. Most of those sixteen years, minus a few periods of time spent at friends’ homes in New England, Bishop lived in Brazil. Possibly because of her long absence from the United States, her reputation suffered.

If so, she didn’t seem to care. She believed in working hard on both poetry and her love life, less so on her reputation. She took on domestic life with a passion, fantasizing about it with some humor: “I can set myself up with a little shop in Rio, an impoverished gentlewoman, selling doughnuts and brownies.”

Impoverishment, though, was never a real threat to her in Brazil. Macedo de Soares was very wealthy, and she supported Bishop during their years together. When she and Bishop returned from New York to Brazil after a short separation, they traveled with “twenty-six pieces of luggage, as well as three barrels, four large crates, and seven trunks, packed in the ocean liner’s hold.” Hardly an impoverished poet’s baggage.

Eventually, the relationship ended (with Bishop beginning another affair before the break-up – “How could finding love again when she needed it be a sin?” Marshall asks, imagining what Bishop herself might have been thinking.) Bishop came back to the United States in need of distraction, and she began reluctantly to teach. She was the first woman to teach a creative writing course at Harvard, and the first woman to be listed in the Harvard course catalog.

Her drinking, a problem throughout her life, grew worse. She fell several times over the next few years, breaking bones and making rumors fly about her alcoholism. As Marshall says, “…poetry and alcohol had become organizing principles” in Bishop’s life. A long list of pharmaceuticals were added on – pills to wake up, pills to go to sleep.

Eventually, another new lover, a young woman more than thirty years her junior named Alice Methfessel, proved to be a loyal partner, tolerant of Bishop’s alcohol and pills. Marshall takes advantage of a collection of letters to Methfessel unavailable to biographers until after the woman’s death. There was a short period when the two separated, but once Methfessel returned to Bishop, the couple stayed together until the end of Bishop’s life. Still, they did not express affection in public – they referred to each other as friends, and they behaved as the same, never embracing, never holding hands. In fact, they seldom touched, even around close friends.

Marshall, who studied for a brief time with Bishop at Harvard, justifies a unique approach to the book’s structure by quoting this passage from The Confessions of a Biographer by Gamaliel Bradford:

Every living human being is a biographer from childhood, in that he perpetually studies the souls of those about him, detects with keen and curious thought the resemblances and differences between those souls and that still more present and puzzling entity, his own, and weighs with the most anxious care the bearing and effect of others’ thought and actions upon his own life.

The book opens with Marshall’s recollections of the Harvard memorial service for Bishop. She then adds, in its entirety, a Bishop sestina titled “A Miracle for Breakfast,” from which the subtitle of the book is taken. The sestina – a particularly difficult and rule-heavy form involving lines with a series of six end-words repeated in a ornately strict order in six stanzas, followed by an envoy containing all six words – ends in a melancholy mood, suggesting that the “miracle” of happiness was happening just out of reach, on “the wrong balcony” – not Bishop’s.

Like the sestina, the book is organized into six chapters, using the same end-words Bishop chose for her poem (Balcony, Crumb, Coffee, River, Miracle and Sun.) Those chapters are interspersed with sketches which jump forward in time and involve Marshall’s interactions with Bishop. And like the sestina, the biography ends with an envoy.

Unlike some reviewers, I found the occasional chapters about Marshall’s first-hand experiences with Bishop to be intriguing, not disruptive. We see the poet through a different lens altogether, focused specifically on how she performed (or, sometimes, failed to perform) as a teacher. We also see the future biographer at work as a poet; we’re able to consider why poetry, for her, comes up short (and why she comes up short for poetry.) And, as the epigraph suggests, we are given a theme: How do we read biography as a way to understand the resemblances and differences between someone else’s life and our own?

Should a biography end by focusing on the biographer rather than the biographer’s subject, as this one does? It’s unusual, but the approach stays true to the opening epigraph. Marshall clearly wanted to explore, sestina-like, the “resemblances and differences” between her choices and Bishop’s, measuring the effect Bishop might have had upon her own life. She does know how to look at Bishop’s poems intelligently and understands how to describe their word-choices and intricate rhythms. Her early training in poetry, her understanding of the poetic toolbox, makes her well-qualified to take poems apart to see how they work.

I found myself wishing occasionally that more of Bishop’s poetry had been quoted at length rather than given to us in short bits and pieces. Taken out of context, a line of poetry – especially one by Elizabeth Bishop, whose control of tone and sound was unique – can lose its author’s idiosyncratic voice, its musical qualities and its mystery. Prose from Bishop’s journals and letters also suffers too often from being taken out and quoted in phrases and small snatches.

But Marshall does do a good job of letting her readers know what early versions of Bishop’s poems sounded like. The revision process – essential to Bishop, who sometimes kept her poems “in process” for years before publishing them – is underscored, and we see how perfect the final version is.

Much of the last section of the book (“Sun”) describes the writing and revising of a villanelle that is Bishop’s most famous. Titled “One Art,” it is everything a poem should be: restrained, wise, clever, technically perfect, and (in combination with these, and most important) heart-felt. Facts gleaned from Marshall’s biography (places Bishop meant to travel, names she forgot, homes she left behind, people she loved and lost) are evident. This is a poem written from Bishop’s own experiences, less emotionally distant than many previous poems. The sorrow in it increases with each interpretation of the word “losing”:

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it might look like (Write it!) like disaster.

The book ends with 44 pages of notes – interesting if you want to follow-up on some of the sources from which the author compiled her account of Bishop’s life.

Marshall’s research skills cannot be faulted, and this new biography makes for a revealing, if oddly structured, examination of Bishop’s complicated life and work. A fine follow-up book would be Colm Toibin’s examination of Bishop’s poetry (including biographical details) in his 2015 book On Elizabeth Bishop, part of the Writers on Writers series. You can also read a wonderful response by Toibin to the 92nd St. Y’s recording of Bishop reading her work in 1977, just two years before her death.

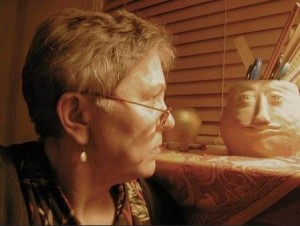

—Julie Larios

Julie Larios has written several reviews and essays for Numéro Cinq. You can find them archived here. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. She recently retired from the faculty of The Vermont College of Fine Art and currently lives in Bellingham, Washington, about ninety miles north of Seattle and forty-seven miles south of Vancouver, B.C. For approximately the next three and one-half years, until the election of 2020, she will be fantasizing about becoming a Canadian.

.

.