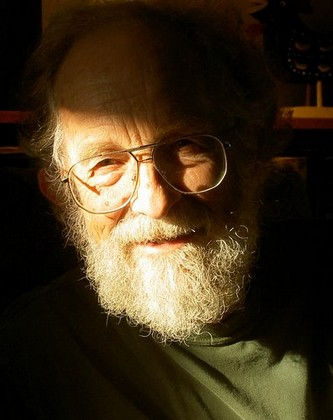

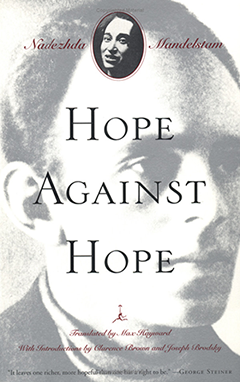

Whether you write fiction or nonfiction, here’s a practical look at the utility and felicities of research from a former journalist and Pushcart Prize-winning fiction writer, Russell Working. I met Russell years ago when he was staying the Yaddo, the art residency in Saratoga Springs. I wasn’t at Yaddo, but I live about six minutes away and am always going over there to visit (or rescue) friends. Russell won the Iowa Short Fiction Award for his first book The Resurrectionists and then spent six years as a freelance reporter in the Russian Far East and the Middle East. His fiction and humor have appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, TriQuarterly Review, Zoetrope and Narrative. Of his 2006 collection The Irish Martyr (the title story won a Pushcart Prize) I wrote: The Irish Martyr is a powerful, brave and dangerous book that takes us to the borderlands where religion and geopolitics rip apart the lives of ordinary people. These are stories about torture, decapitation, rape, kidnapping and trafficking in women and babies. They are about men and women caught in the meat-grinder of history, caught between trying to survive as human beings and the vicious tools of dogma, ideology and greed. Russell Working knows the dark corners of the world, he knows the personal underside of the news stories we have become all too accustomed to seeing on our TV screens. He writes straight from the heart, with a moral indignation that is palpable.

dg

—

Many years ago, I was working on a novel that involves a husband who is searching for his missing wife. In it my protagonist, Paul, goes into a morgue with a cop and a coroner to identify a body that might be hers. The question was, how to describe the morgue? No problem! I knew all about that. I had never been in a morgue, but I had seen them on TV and the movies. Good enough.

Plus, I am a fiction writer. That means I can just use my imagination, right? And unlike in journalism, nobody gets to demand a correction. So I wrote it just like on TV, the walls were lined with stainless steel drawers. The coroner pulls one open. And there’s the body, covered by a sheet.

But wait a minute. Dead bodies: it must smell bad. So I had my coroner light up a cigar to cover the odor. He offers cigars to the detective and poor Paul, who thinks he is about to see the corpse of his murdered wife.

“Smoke, gentlemen?” the coroner says.

“He smokes the good stuff,” the detective says. “Cuban seed.”

*

Needless to say, I never sold that novel. And as for that scene, it bogged down in the writing. It was lifeless. I was stuck. I fought my way through it, but the description never stopped smelling dead. The trouble was, I needed to report my story, in the way that a journalist might, to pick up the phone, make an appointment with a coroner, and head out to the morgue with a notebook in hand.

I needed to go to take in the sounds and smells. To interview a staff. To investigate. To research. Scribble notes. Record the interview. Look around the crypt where the bodies are kept. Did it have a high vaulted ceiling or a low one? Were there bare light bulbs or phosphorescent track lighting? Were the walls tile or plaster? Then take it all back to my computer, throw out the dross, and turn the key elements into fiction.

I was a newspaper reporter, yet I had never taken that basic step, at least for this particular scene.

Now, wait a minute, you may say. Why do we need to do this? If we’re fiction writers, don’t we get to make things up? And if the fiction is autobiographical, can’t we just rely on our own memories? We lived it, after all. What if we’re magical realists? What if my protagonist is a centaur or a flying squirrel who thinks he’s Batman? And as for creative nonfiction, aren’t many of us writing memoirs, which means the topic is subjective? Who needs research, to say nothing of shoe-leather reporting?

Well, when we write a scene, whether it is magical realism or a noir tale of murder, we strive to imagine a narrative world that is vivid and believable within the rules it agrees to play by. In one way or another, we seek to establish a sense of verisimilitude. Beyond that, we want our construction of events to seem plausible within the universe of writing. We wish to speak with authority. Reporting and hands-on research will inspire stories and suggest images and characters and the plotline itself.

When a reader takes up a book, he and the author are engaged in a joint act of creation, and he must reconstruct that world in his mind based on the details the author presents in words.

Think of the reader as Hellen Keller: she is blind and deaf and, for that matter, let us imagine that she doesn’t even have a sense of smell. All she relies on is touch: the touch of our words. We sign into her palm, telling her what is out there. She must trust us. We as authors are all she has to experience this created world. She clings to our arm, eager to know what we see and hear, forming pictures of her own within her mind. Thus she, too, participates in a joint creative act by envisioning the scenes and the characters that we sketch with words.

But when we hit a false note, Ms. Keller perceives the author behind the artifice of fiction, dressed in sweats, unshaven, unshowered, slouching in a chair with a cup of microwaved coffee, trying to think of some event to move the story along.

There are days when we all may feel we’re staring at a screen going nowhere. Perhaps these, most of all, are the days that could stand the help of reporting. The writer who thinks his job is confined to his desk at home is much more likely to trip up readers with phony descriptions or outlandish turns of plot. He yanks Ms. Keller out of the joint act of dreaming and thrusts her into the role of skeptic.

In 1989, Harpers Magazine published an essay by Tom Wolfe titled, “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” a manifesto that was as bombastic and full of itself as its title. Wolfe quoted his own fiction approvingly and at length, and took it upon himself to denounce many of his contemporaries, who were angered and bewildered by his tone. The New Yorker described him as crashing a cocktail party and throwing writers around like a professional wrestler. A literary brawl ensued (always a fun thing), with some of America’s leading writers weighing in in the letters to the editor. But amid the uproar, Wolfe outlined some important lessons for writers, and I would argue that these apply both to fiction and creative non-fiction. He stated:

[The] task, as I see it, inevitably involves reporting, which I regard as the most valuable and least understood resource available to any writer with exalted ambitions, whether the medium is print, film, tape, or the stage.

He goes on:

Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Balzac, and Sinclair Lewis assumed that the novelist had to go beyond his personal experience and head out into society as a reporter. Zola called it documentation, and his documenting expeditions to the slums, the coal mines, the races, the folies, department stores, wholesale food markets, newspaper offices, barnyards, railroad yards, and engine decks, notebook and pen in hand, became legendary. To write Elmer Gantry, the great portrait of … a corrupt evangelist … Lewis left his home in New England and moved to Kansas City. He organized Bible study groups for clergymen, delivered sermons from the pulpits of preachers on summer vacation, attended tent meetings and Chatauqua lectures and church conferences and classes at the seminaries, all the while doggedly taking notes on five-by-eight cards.

Fine, you may say. That was Tom Wolfe, the guy in the white suits and high-collared shirts. The showman. Sure, he writes novels, such as Bonfire of the Vanities, but he cut his teeth on nonfiction like The Right Stuff. Of course he would recommend playing the reporter.

And as for me, I am a newspaper reporter by profession. Of course I am going to plug the skills of my dying medium, which is going the way of the town crier.

So how about a literary figure who is more in tune with the spirit of our times?

As it happens, not everyone agrees with Wolfe. Consider Jonathan Franzen, author, Freedom, which propelled him onto the cover of Time magazine. He argues that these days research doesn’t matter much—including, presumably, the reporting, notebook in hand, that I recommend.

In February he was asked to contribute a list of rules of writing to the Guardian. Number 5 was this: “When information becomes free and universally accessible, voluminous research for a novel is devalued along with it.” Likewise, in an interview, he says, “I avoid [research] as much as possible. It gets in the way of invention.”

So is Wolfe wrong, or embarrassingly passé? Are we at our best when we discipline ourselves to remain at the desk and just pound the words out, unleashing the magical forces of our creativity?

In the age of Google, are we just wasting our time when we go out and scribble notes about the slaughtered lambs hanging in a halal butcher shop or the Chicago ex-cons selling jars of organic honey at a farmers market? If we are out jotting impressions in notebooks, aren’t guys like Franzen racing ahead by sitting at his desk and applying himself to the actual writing of books?

Time magazine hailed Franzen as “A Great American Novelist,” and nobody has called me up to sit for a cover portrait. No doubt his greatness contains such multitudes that he could write just as well from a padded cell. Perhaps only we hacks need to actually look at the things we are describing, the way minor artists like Michelangelo and Da Vinci looked at live models when they drew the human form.

But I shall let you in on a secret: even Franzen doesn’t really believe what he is telling you. It strikes me as so unhelpful, I almost wonder if he is trying to winnow the competition by sending young writers up the wrong path.

Ha! They believed me, the suckers!

Here is why I know he isn’t being entirely straight with us. In the very next sentence of that interview I just cited, he admits that he traveled to West Virginia for four days to investigate coal mining communities for Freedom. He also said he had the help of others in researching Minneapolis neighborhoods, even though he himself is from Minnesota.

The research shows. He writes of the “matchstick Appalachian woods and the mining-ravaged districts.” He describes an hourglass-shaped vein of coal that lies under the mountains, at the center of which lives a clan headed by a man named Coyle Mathis, who is refusing to sell his ancestral home to a company that plans to remove the mountaintop, mine the coal, and create a nature reserve. When Mathis receives an offer to buy his property, Franzen writes, he “didn’t even wait to hear the details. He said, ‘No, N-O,’ and added that he intended to be buried in the family cemetery and no one was going to stop him.” When Mathis threatens to sick his dogs on the man making the offer, even shoot him, the scene has an authenticity that surely owes something to Franzen’s reporting in West Virginia.

So how do we use research and reporting to enhance, rather than obstruct, creativity? Here are some recommendations:

1. Get out.

As writers, we tend to feel that the only work that matters is that spent in front of the computer, pushing up the word count displayed at the bottom of the page. But simply getting up and getting out into the world can make the words flow afterwards, whether we’re heading to an A&P, like John Updike, or a scrap metal yard or a foreign country.

In Michelle Huneven’s novel Blame, an alcoholic history professor with a wild streak, Patsy MacLemoore, wakes up in jail after blackout. Patsy’s story begins thus:

Patsy MacLemoore came to on a concrete shelf in a cell in the basement of the Altadena Sheriff’s department. Her hair had woken her up. It stank.

She had said she would rather die than come back here. She’d said that both times she’d been here before.

The little jail had no windows. Fluorescent tubes quivered night and day. A fan clattered, off-kilter. Each of the three connected cells contained a seatless stainless-steel toilet and a tiny, one-faucet sink.

Lurching to the undersized sink, she drank from it sideways, cheek anchored against the greasy spout. The dribble was tepid and tasted of mold. In the next cell over, June’s haughty face loomed. Did she fuckin live here? Every time Patsy’d been in, she was, too. June’s top lip was like two paisleys touching. What’d you do this time, Professor? said the lips.

Don’t know, Patsy said. …

Not what I heard, June said. And lookit your face.

Patsy’s fingers went to a ridge of scab crystallizing along her cheekbone. No wonder her head hurt.

Returning to the shelf, she noted the itchy rasp of the prison gown. Lead-blue, unrippable, it was made of 45 percent stainless-steel, according to the label. She was naked beneath, not even panties.

I hear you’re in deep shit, Professor, [June said].

It is not until Patsy is sitting opposite two cops and her own lawyer does she begin to comprehend what she has done. She is tossing out flippant remarks—“We have to stop meeting like this”—when she sees a file in front of the detective. On it is written, HOMICIDE.

She learns she has been accused of running over and killing a mother and daughter while driving drunk. Her whole life as she knew it is over and she is heading for prison.

In an email, I asked Huneven how she was able to portray so convincingly the events including Patsy’s time in jail and a prison firefighting camp. Her discussion of how she researches illustrates my point. Huneven interviewed widely. She talked to everyone she knew, male and female, who had been in prison or jail. She unearthed subplots and storylines in real life.

She wrote me, “One woman in particular—she’s essentially Gloria in the book—talked to me at length; she’d been sober forever, but was manic depressive. With twenty years sober, she got off her meds, stole a hundred thousand bucks from her boss and drove across country delivering it to poor people she met at McDonalds and the like. She was sentenced to 4 years, served two, part of it in fire camp. For the firefighting details I interviewed a young woman I know who recently spent two summers fighting fires in the Sierra.”

Equally important, she visited the scene. Lacking Franzen’s mystical abilities as a seer, she was forced to trudge on down to a courtroom in person and spend a day observing what went on.

She writes:

“I interviewed prosecutors, who in turn did research for me about how much time a drunk driving/ criminal negligence charge would get you in the early 1980’s. I was momentarily stumped when I found out that they couldn’t prosecute for drunk driving because the accident happened on [private] property, but that ended being up a rather interesting part of the narrative, I thought. I interviewed a probation officer, I actually made my husband, who is a lawyer, write the declaration that frees Patsy from responsibility in the end. He gave me SUCH a dull document my agent made me slice it back to the few salient sentences.”

In my own writing, getting out of the office has inspired some of my best-received stories. I used to live in the Russian Far East, and I made five reporting trips to China. On one trip I encountered a couple whose lives would inspire a short story in my collection, The Irish Martyr.

In China when a freelance reporter such as myself asks around in a hotel for an interpreter, an uncomfortably friendly middle-aged man with hair dyed shoe-polish-black will show up in a white sedan with a soldier at the wheel and red flags flapping from the bumpers. Because I usually did business reporting, this never was a problem.

But on one visit I wanted to write about a highly sensitive topic, North Korean refugees. I couldn’t rely on the official story. Through friends I found an interpreter, and by sheer luck he knew of a refugee.

She had escaped North Korean, her hair thinning from malnutrition, and was sold as a wife to a Chinese peasant. In my story, “Dear Leader,” I described the day she is taken to meet her new husband. Let me do a Tom Wolfe and approvingly quote my own fiction:

An ethnic Korean marriage broker named Bong-il drove her to her new home near Yanji, rasping dire warnings all the way in the back seat of his smoky Land Cruiser while his driver adjusted the music on the stereo. “If you run away, we will find you, understand? He is paying good money for you, and we are men of our word. We will return you, and you’ll discover what an angry husband can do to a girl. I know this one guy, he chained his wife to the bed and gouged her eyes out the third time she tried to run away. If we don’t find you, the police will, and you know what that means: back to North Korea. Stay put. Even if he beats you, you’ll be fed, unlike in Hongwan, right? You will live. Seems like a fair bargain.” He threw his cigarette butt out the window and asked, “Are you listening?” She was. “Good,” he said, “because I’m not trying to scare you, I hope you’re happy, I truly do, you are such a pretty girl, or you will be when you fatten up and your hair grows back. … Incidentally, it’s his prerogative to resell you if he wishes. Maybe that isn’t so bad. Think of it this way: if you don’t get along, maybe you’ll end up with someone more compatible.”

This monologue was inspired by the refugee’s description of the conditions under which she arrived. In fact her very predicament is drawn from my interviews with the real-life refugee woman and the husband who had bought her.

We mere scribblers cannot invent such situations. We go out and sift through the infinite range of stories the world offers us. And it amazes us.

2. Find a Guide.

Dante had Virgil to guide him in his pilgrimage through hell, purgatory, and heaven. If you are overwhelmed in an unfamiliar area or topic, find a guide.

By way of example let us consider George Packer, a reporter for the New Yorker. In a 2007 nonfiction piece, Packer described meeting two young Iraqis in Baghdad. Othman was Sunni, Laith was Shiite.

Packer met them at the Palestine Hotel, where, two years earlier, a suicide bomber driving a cement mixer had triggered an explosion that nearly brought down the hotel’s eighteen-story tower. He writes:

It had taken Othman three days to get to the hotel from his house, in western Baghdad. On the way, he was trapped for two nights at his sister’s house, which was in an ethnically mixed neighborhood: gun battles had broken out between Sunni and Shiite militiamen. Othman watched the home of his sister’s neighbor, a Sunni, burn to the ground. Shiite militiamen scrawled the words “Leave or else” on the doors of Sunni houses. Othman was able to leave the house only because his sister’s husband—a Shiite, who was known to the local Shia militias—escorted him out. Othman took a taxi to the house of Laith’s grandfather; from there, he and Laith went to the Palestine, where they enjoyed their first hot water in several weeks.

These two men became his guides. Packer says in an interview with the Poynter Institute that this is his general practice. “I need someone who can provide me with the introduction to the place and give me sense of the landscape,” he says.

For a story on the U.S. Senate, Packer relied on the insights of beat reporters who knew the ins and outs of the institution, along with the staffers familiar with its obscure rules. When he decided to investigate the roots of the financial meltdown, he chose Tampa in part because a friend there could show him around. The two canvassed the Tampa Bay area, driving through subdivisions and taking to people randomly. What he learned in those interviews became the core of the story.

“Once I get there, I’m constantly saying, ‘Who else should I talk to?’ ‘Do you know anyone in this situation?’ ” Packer says. “And people tend to be quite generous with that information, and most people want to tell their story.”

Fiction writers also may find a guide helpful in unfamiliar territory. In interviews, Colum McCann has talked about how he lived with homeless people in the subway tunnels and traveled to Russia to research another novel. But the book I wish to discuss is Zoli, is about a Roma, or Gypsy, singer and poet born in Slovakia in the 1930s during the height of fascist power in Europe.

In it, the six-year-old Zoli, who will become an acclaimed singer and poet, learns from her grandfather that fascist militiamen have driven her clan and its wagons and horses out onto the winter ice and encircled the shore with fires. The ice collapses and the people drown. Zoli tells us, “My mother was gone, my father, my brothers, my sister and cousins, too.”

The book has been praised for its realistic portrayal of the life of Roma, a society that has long been persecuted and also closed to outsiders. Its descriptions struck me as deeply authentic. Consider this description of a visitor enters a Roma settlement:

Doorframes used as tables. Sackcloth for curtains. Empty çuçu bottles strung up as wind chimes. At his feet, bits of wood and porridge containers, lollipop sticks and shattered glass, the ground-down bones of some dead animal. He catches glimpses of babies hammocked from ceilings, flies buzzing around them as they sleep. He reaches for his camera but is pushed on in the swell of children. Open doorways are quickly closed. Bare bulbs switched off. He notices carpets on the walls, and pictures of Christ, and pictures of Lenin, and pictures of Mary Magdalene, and pictures of Saint Jude lit by small red candles high above empty shelves. From everywhere comes the swell of music, no accordions, no harps, no violins, but every shack with a TV or a radio on full volume, an endless thump. …

He is led around a sharp corner to the largest shanty of all. A satellite dish sits new and shiny on the roof. He knocks on the plywood door. It swings open a little further with each knuckle rap. Inside there is a contingent of eight, nine, maybe ten men. They raise their heads like a parliament of ravens. A few of them nod, but they continue their hand, and he knows the game is nonchalance—he has played it himself in other parts of the country, the flats of Bratislava, the ghettos of Presov, the slums of Letanovce.

In an interview McCann discusses his research methods. He says his guides, Martin and Laco, introduced him to writers, musicians, ethnographers, sociologists and Roma activists. He went to the most notorious Slovakian settlements to see the conditions of life there: the mud and wattle huts, the poverty, the desolation. No electricity, he says. No running water. He sang old Irish songs, hung out and watched what they did. He was an outsider, dependent on others to show him around, but he showed empathy and tried not to intrude.

He adds:

[O]ne day I was in Svinia … [and] a big group of kids and I went down to the local soccer pitch to play football together. We were playing away happily, quietly. But then these “white” women started shouting at us from a distance. Before we knew it we were hounded out by the mayor and the local policemen who called us “fucking Gypsies.” Except they were a bit puzzled by me. They kept staring at me. As if to say, Who’s the white boy? … We got kicked out. They locked the gates behind us. I tried to protest in English and apparently they were calling me another bleeding heart, another European sentimentalist. We walked away, back to the settlement. A half-mile along this country road. Quietly. No fuss. No fights. There was lots of broken glass at the field near the settlement. That’s why we couldn’t play there and had to go to town.

But therein lies the dilemma. I could make this a story about being treated terribly by the local authorities. That’s true, but it’s also true that nobody smashed glass on that field other than the Roma themselves. The kids had ruined their own field. That’s the heartbreak. That’s the contradiction that fiction, too, has to find.

Moments like that are hard to create from an office chair in front of your laptop.

;

3. Talk to sources who have lived the life you’re writing about.

Interview taxi drivers, garbage men, street preachers, beauticians, aldermen, astrophysicists, the homeless Poles who sleep in dumpsters in Chicago—whomever you’re writing about.

In November 1959, two ex-cons entered a farmhouse in Holcomb, Kansas, and murdered the owner, his wife, and their two children. It was a horrific, senseless, random crime of the sort that makes headlines nationwide and then vanishes into the criminal system. But Truman Capote saw behind the headlines a powerful story worthy of a great writer’s attention, and he decided to pursue it for his so-called “non-fiction novel,” In Cold Blood. He and his assistant, Harper Lee, traveled to Kansas. At the courthouse they tracked down the Kansas Bureau of Investigation agents who were handling the case.

In 1997 George Plimpton wrote an oral history on the writing of the book for the New Yorker. He recounts how Capote left a singular impression with the people he spoke to.

One agent tells Plimpton, “Al Dewey [a KBI agent], invited me to come up and meet this gentleman who’d come to town to write a book. So the four of us, KBI agents, went up to his room that evening after dinner. And here [Truman] is in kind of a new pink negligee, silk with lace, and he’s strutting across the floor with his hands on his hips telling us all about how he’s going to write this book.”

My point is not that we all need to wear pink negligees when we’re interviewing cops. Rather, is that Capote, a gay New Yorker, was bold enough to go into an alien milieu, that of homicide detectives, and win their cooperation, despite some outrageous behavior. He obtained extensive interviews with nearly every major person in the book, including the murderers themselves.

KBI agent Alvin Dewey said, “He got information nobody else got, not even us.”

(Truman’s breach of ethics in achieving this scoop are a matter of discussion for another day.)

*

Last year I dug up that old novel of mine—the one with the cigar-smoking coroner—and I blushed when I read some of the scenes. But still, I thought it was worth another go, and after a revision, so did my agent.

When I first dove into the manuscript again, I decided to research every major element of the plot. I interviewed cops and day laborers and a guy who paints houses for a living. I found two University of Chicago surgeons who treat bullet wounds, and I sat in on the class of an Aikido instructor.

A cult plays a central role in the novel so I interviewed a woman who had spent two decades in Tony Alamo Christian Ministries; its leader is now serving a 175-year sentence in federal penitentiary for taking girls as young as nine across state lines to have sex with them. I listened to sermons by the Rev. Jim Jones, who led 900 of his followers to their deaths. I interviewed the CEO of a nonprofit dedicated to the rescue of big cats such as lions and tigers.

Since writing the original draft I had visited a morgue in Russia, but I still sought out an investigator at the coroner’s office in Los Angeles. That, after all, was where the book was set. She agreed to talk to me, but she said we could not under any circumstances, see the crypt—the area where they store the bodies—or the rooms where the autopsies are done. All we could do is meet in her office.

I was a little disappointed, but it was better than nothing.

We looked at all kinds of grisly photos. As I described the situation in my novel, she would show me pictures. She saw that I wasn’t going to throw up on her desk when we saw the grim images. When I asked about the layout of the crypt, she said, “Oh, hell. Let’s just go look at it.”

And suddenly we were trotting downstairs, donning surgeon’s masks—which kind of hindered our cigar-smoking—and marching in to see the room where several hundred bodies were stored.

Now, I’m not going to give away all my hard-earned research to other writers. Needless to say that in this particular morgue, at least, was nothing like what you see on TV.

There is no substitute for seeking out sources. If your character is a high school football coach, call one up and ask if you can drop by practice some afternoon. If she is a lawyer or a foot masseuse or a Ukrainian baker, go find one to talk to. If you want to write about a journalist, talk to one.

If you are writing a memoir, be willing to interview your family or friends or others who lived the experience you are writing about.

All right, but how do you reach the people you need to talk to? Admittedly, it is harder for a fiction writer than a newspaper reporter, but it is not impossible.

For the LA County Coroner’s Office, I dug up a story that quoted a woman extensively, and called her directly. I simply told her I am a writer working on a novel, and I wanted to get things right. She seemed pleased at my diligence. To talk to a cop, I called the LAPD public affairs office. The spokeswoman told me she doubted any detective would talk to me, but she said she would ask. It turned out the head of the department was intrigued by my project and was willing to help.

If the official sources say no, try a back door. Talk to friends and put out feelers to reach people.

Record your interviews. Interestingly, Capote didn’t do this, but he claimed to have had near perfect recall. He said that when he was a boy, he would memorize pages of the New York telephone book. Then he would have somebody quiz him: “On line so-and-so, what’s the name there and what’s the telephone number.” He didn’t even take notes; he and Lee would return to their rooms and write down their recollections of conversations afterwards.

For mere mortals, a good recorder is essential. In writing Executioner’s Song, Norman Mailer and his collaborator Lawrence Schiller said they recorded hundreds of hours of interviews amounting to thousands of pages of transcripts. This is why the voice so closely parallels those of the characters whose lives it recounts. I have a little Sony digital recorder that you can plug it into your computer when you get home, so you can download the audio file and transcribe it later. As you do, this will help you accurately recall what they said. It gives you a sense of your source’s voice, character, thought patterns, and manerisms.

Once you have talked to your sources, something interesting happens. They become a Council of the Wise whom you can consult with further questions. Ask them for their email address. You need to use them judiciously, but they are great for checking out details. Don’t send lists of 20 questions or they won’t reply, but use them.

I did this with the coroner’s investigator. The missing persons detective had told me a rather amazing story about how a cadaver dog sniffed up a homicide victim. But I needed to know who would respond to a scene where a body is found in a backyard. I emailed my source in the coroner’s department, asking how many personnel would show up, and she sent me a long email in reply. Here is just a small part:

Shallow Grave in a backyard: Personnel present: Police Department Homicide Detectives & Photographer, Coroner Special Operations response team (Handling Investigator, Criminalist, Forensic Anthropolgist, Photographer and Cadaver Dog & Handler -remaining team members consisting of other Investigators, Forensic Attendants and Criminalists).

.

4. Do your homework.

Fine, but how do we know what sources to seek out? Of course, this is often plain from the work itself. But it also helps to do your homework. Before McCann traveled to Europe to research the Roma, he spent a year in the New York Public Library. Huneven had done a major investigative piece on the California Youth Authority years ago, and she drew off of the contacts she made them.

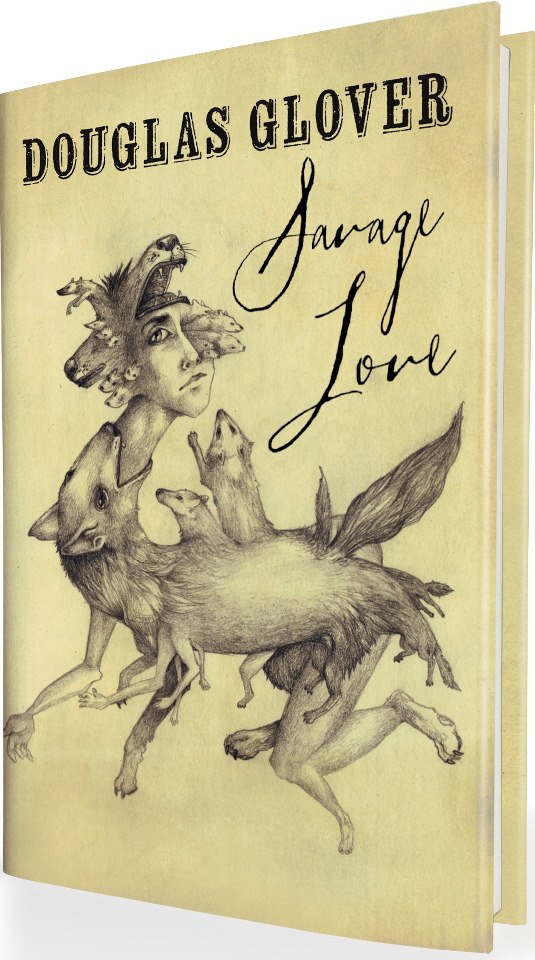

Doug Glover has a novel named Elle, about a lusty young French girl whose shipmates abandon her on an island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence during an early expedition to colonize Canada. She is found by a native hunter, who becomes her lover and helps her survive, and she is drawn into what has been called “a bear-haunted dream world.” She even shape-shifts into a bear.

The novel makes heavy use of aboriginal mythology and magic. And yet what also interested me was the vivid realism in its portrayal of 16th century France and native life in its newly established colonies. It feels grounded in reality. The myths it describes are convincing. In his acknowledgments Doug, says he plundered many books to come up with a compelling vision of life that era. But he also tells me that in researching the novel, he talked to a librarian at a reservation who had archived tapes of interviews with old Indians.

Doug also hunts through bibliographies looking for papers published in journals, especially old ones. He would find a paper, and from its bibliography and get even more sources.

“The key to research is that you’re looking for the fact that is not commonly known,” he told me. “It infuses your writing with authenticity, if it’s real yet somewhat surprising.”

He also offers a hint for those who are uncomfortable with the idea of interviewing. Doug says he would never go up to an Indian and ask him about anything directly. But if you hang around, you start to get a feel for things such as way they name and nickname people and the kind of humor they have.

Thus he gives his characters names like Comes Winter, an Indian girl who was kidnapped and taken to France and is dying of consumption. One little boy is named Old Man, while an old man is named Gets Close to Caribou.

Gets Close to Caribou earned his name one winter when a panicky caribou spooked in the wrong direction and almost trampled him to death. Gets Close was unconscious for a week—he dreamed the caribou lifted him in its mouth and carried him to Caribou Mountain, north of the Land of Nothing. He stayed with the king of the caribou, a former hunter who had fallen in love with a caribou-woman. All present-day caribou are descended from this hunter and his caribou girlfriend.

In my own case, in reporting for my fiction, I have gone to the federal courthouse in Chicago and pulled records on an ongoing Russian mafia trial, including indictments and transcripts of FBI wiretaps. This gave me the chance to read about the father-son team of money launderers Lev and Boris Stratievsky. The father was nicknamed Dollar, the son Half-Dollar. Great names! I didn’t use those in my fiction, but they set my imagination running.

The two were laundering millions of dollars as a part of a broader criminal network of Eastern Europeans. They were shipping stolen cars and heavy machinery abroad, peddling drugs and guns to Chicago street gangs, committing mortgage fraud, and trafficking in young women. These reports provided a rich background that allowed me to think more expansively about the mobster at the center of my story. For one thing, I moved my mobster out of a Chicago two-flat into a mansion on Lake Michigan.

Think creatively. You can also request military records to find out if that veteran you are writing about is telling the truth about the Navy Cross he claims he won or whether he even was in Vietnam, let alone butchered all those women and children he butchered there.

You are all familiar with the Internet, but I will say two things.

1. It can be a marvelous research tool for original documents, even if you don’t have access to legal databases. For example, there is a web site that has extensive documentation, including original court records, on American jihadists who have been convicted on terror charges.

Elsewhere, you can find FBI transcripts of Jim Jones urging his followers to commit suicide in Guyana, and one woman arguing, futilely, that the children should be spared.

2. But the Internet can be a deadly trap. It keeps you at your desk, rather than getting you out into the world. It’s tempting to check out Google street view rather than drive to that neighborhood with a notebook in hand. It is also a distraction. Franzen warns about this with his usual hyperbole: “It’s doubtful that anyone with an internet connection at his workplace is writing good fiction.”

§

Let me conclude by returning to Tom Wolfe. His point is not merely that on-scene research and reporting create verisimilitude and make a novel gripping or absorbing, although these are important. Rather, he states, this kind of reporting is essential for the very greatest effects literature can achieve. Wolf writes:

In 1884 Zola went down into the mines at Anzin to do the documentation for what was to become the novel Germinal. Posing as a secretary for a member of the French Chamber of Deputies, he descended into the pits wearing his city clothes, his frock coat, high stiff collar, and high stiff hat … and carrying a notebook and pen. One day Zola and the miners who were serving as his guides were 150 feet below the ground when Zola noticed an enormous workhorse … pulling a sled piled with coal through a tunnel. Zola asked, “How do you get that animal in and out of the mine every day?” At first the miners thought he was joking. Then they realized he was serious, and one of them said, “Mr. Zola, don’t you understand? That horse comes down here once, when he’s a colt, barely more than a foal, and still able to fit into the buckets that bring us down here. That horse grows up down here. He grows blind down here after a year or two, from the lack of light. He hauls coal down here until he can’t haul it anymore, and then he dies down here, and his bones are buried down here.” When Zola transfers this revelation from the pages of his documentation notebook to the pages of Germinal, it makes the hair on your arms stand on end. You realize, without the need of amplification, that the horse is the miners themselves, who descend below the face of the earth as children and dig coal down in the pit until they can dig no more and then are buried, often literally, down there.

The moment of The Horse in Germinal is one of the supreme moments in French literature—and it would have been impossible without that peculiar drudgery that Zola called documentation.

— Russell Working

——————————-

Russell Working is the Pushcart Prize-winning author of two collections of short fiction: Resurrectionists, which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award, and The Irish Martyr, winner of the University of Notre Dame’s Sullivan Award. His stories and humor have appeared in publications including The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, TriQuarterly Review, Narrative, and Zoetrope: All-Story. A writer living in Oak Park, Ill., he spent five years as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. His byline has appeared in the New York Times, BusinessWeek, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the South China Morning Post,the Japan Times, and dozens of other newspapers and magazines around the world.

Robert Day‘

Robert Day‘