Mark Anthony Jarman

Mark Anthony Jarman

.

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, poet (1792-1822)

.

Pope Rat watches Euro Cup, the blind man wanders our hotel halls, and I wander Rome’s swarming city. I soak my head and T-shirt in cold water to escape the Roman heat, I inhale cold bottles in a dark bistro, then I creep into another empty church – simple, not a rock-star church, but I must look. The streets burn in wild daylight, but inside is shadow, inside my eyes rise to a blue dome where a young Italian artist painted night stars inside the cupola before spilling from his high scaffold, the falling man ending his art and life in one downward stroke.

Ever so slightly sunburnt and intoxicated, I am in the precisely right state to take in the swooning gift of these stars glowing in a tiny compass of sky, this is exactly what a place of worship should do, lines of light guiding my eyes from the well bottom up to these high stars in a circle.

My cells vibrate happily, my mind and eyes ready to receive this perfect sacrament. Light like blocks of white stone fills the church windows, and in my head Gene Clark’s tremolo voice singing, ain’t it good to be alive. This temporal bliss won’t last, but in the moment its echo is beautiful.

Our world revolves about me for a few hours until like Galileo I know, what heresy, it doesn’t circle me, I remember I am millions of miles from the centre. But I’ll survive, I have options. What of the woman from Iraq with her injured eyes? She was once so happy, on her way to college she steered a blinding gold Mustang through the heart of Baghdad and courted bright ambitions, but after the invasion she has nothing, finds herself so far from the centre.

American soldiers liked the woman from Iraq and Americans ran over her gold Mustang with a tank while she was trapped at the steering wheel and then I meet her in her new life in Rome, in her exile. Birds and countries flying through the air like scalding shrapnel, all these wax nations, all these melting borders and homes. Our hotel rooms have teensy televisions bolted to the ceiling and mine pulls in a German MTV channel, rock unt roll, the VJ’s narration an unsettling mix of Teutonic Girl and Valley Girl. Our alliances and kingdoms fidgety as a blackbird’s eye.

.

Loaded down by buckets of dirt and rocks, men trudge out of the earth carrying rocks by hand through the hotel atrium, lugging buckets to a tiny truck the size of a scooter. In a silent prayer I call upon the backhoes of the nation to help them.

I want to chat up the soft-eyed Spanish woman who inhales cigarettes in the atrium. In her white sundress blood speaks in her skin and she reminds me of Natasha, a similar face and hair, as if I know this person, a sister-messenger, though Natasha is too health-conscious to smoke, Natasha is more green tea than Pall Malls.

.

Angelo owns the rambling hotel, Angelo delivers to our atrium party a giant vat of purple-black wine that resembles Welch’s grape juice, a giant ham, prosciutto di Parma, and a giant knife; Eve and I glance at the knife warily. Angelo moves slowly to a long table, his grey hair slicked back, a beaked nose like a hawk; he is generous to us, he is regal.

“Tonight we have a super-big party!” exclaims a smiling Angelo.

Eve can’t take the wine’s sweet taste, but Ray-Ray and the others like the hooch well enough. We also carve up a spicy sausage the size of a small pig and an amazing cake filled with light custard. Food is so good in Italy; it’s like being stoned.

Father Silas makes a toast, “Thanks to the hotel owner for a festa with real Italian girls.” And it’s true, Angelo did arrive with smiling Italian girls with big hair like Amy Winehouse or the Shirelles.

“The bigger the hair the closer to God,” says Eve.

“Grazie, grazie,” we all intone. Grazie. Am I saying it right?

Basta, Angelo says modestly. Enough.

Father Silas whispers to me, “If Angelo says Ciao to us, then we can say it to him.” Otherwise Father Silas worries we might be too informal.

.

The Spanish woman says Angelo’s men are digging a cellar for a basement cafe and gym. Angelo is ambitious, owns many buildings, and I find myself wondering how much real estate he has. Or how he owes. The crew has no jackhammer or bobcat. Excavators and dump-trucks are too wide for the narrow lane. So the work is done by hand and back and legs, like labour scratched out thousands of years ago. Will the men’s picks and crowbars stab into artifacts, find bones in a well? Will our hotel collapse?

Every time they dig in Rome they find something, the Spanish woman says, reading my mind. It is impossible to do anything. If they try to expand the subway, the new line they can dig, a tunnel is narrow, that is okay, but a new station means excavating a much broader space and then they find a temple to Saturn, to Venus, they find a villa, they find rude frescoes, and work is halted. A stray cat crawls into lost catacombs and they must bring in specialists in archeology and incest. So apologies to the world, but Rome will have no new subway lines.

.

Bottles of champagne arrive, like the hand-cut prosciutto, courtesy of generous Angelo, and the champagne thrills Tamika, she scrambles for her camera to snap photos of the large dark bottles. I find this endearing, and wonder if Tamika wants the photos to show her parents or grandparents that she moves in champagne circles. Or perhaps they worry she isn’t having fun in Rome and here is evidence to send them, truthful or not.

I feel guilty lounging around with Eve and Tamika and the Spanish woman while the men work in this heat, passing by us with buckets of rocks and earth. They must think me a rich tourist, that I am lazy, that I am lucky. Am I lucky, I wonder. They dig under the hotel and I hope the undermined foundation will be all right.

.

Angelo’s cured ham is scrumptious and the soft-eyed Spanish woman sips spring water inside her cigarette fog, says, “I am here from Madrid to help a friend at the hotel, a woman. I am not staying at this hotel, I am staying by Termini. Do you know my friend? Do you know Madrid?”

“Madrid is a beautiful city; I was there many years ago.” I struggle for memories: such striking architecture and art deco and oil paintings in the Prado and parks and tabernas, but what I recall mostly is summer heat ballooning in an airless upstairs room by the Puerto del Sol, the temperature driving me from the old hotel and driving me from the city to a cooler sea and a smaller harbor town. Perhaps the Spanish woman loves the heat, like Natasha. The Madrid hotel was shelled during the Spanish civil war. And I remember St. Sebastien and the threat of bombs in Basque country. Does Natasha still keep her hair long, light striking her like a saint?

.

Eve wears a fichu cape and a cute Oriental coolie hat to fend off the sun. An Italian man in the courtyard stares at my cousin Eve’s white t-shirt, a low scoop top that reveals the top of her breasts. He speaks to her breasts in heavily accented English.

“Oooooh, look at you! That is a very nice shirt. My wife has been in the hospital for eight weeks, that’s her over there.” He points to a weary-looking woman glued to a phone, but his eyes stay riveted on my cousin’s chest.

“She was really sick. Yes, her kidneys I think, I’m not sure, but oh she was in so much pain. It was hard to take, but she’ll be all right.” His eyes never lift from Eve’s t-shirt. “You look so goooood!”

My cousin backs up, trying to get away.

“Oooooh yessss, I very much like your beautiful shirt.”

.

I chat with the Spanish woman several times in the atrium, but find I cannot ask her out because I am sure she is waiting for me to ask her out and I hate the moves and the knowledge and the lack of knowledge.

“Are you interested in zombies?” the Spanish woman asks me. Her name is Elena. How do you say dinner and drinks in Spanish (the dream of a common language)? How do you say that you are so very tired of zombies? I wish I had my old phrase book from years ago in Spain. Mucho gusto.

.

Whenever I walk onto my room’s terrace I hear two women talking on their terrace.

We went to Australia, one woman says. We went camping, it was fun. They offered me all kinds of seafood and I said no. We didn’t have money to buy. Well, we had some.

Don’t you wish you’d done some of those things?

You look back. There are memories.

Those are positive memories! Mary, you still have memories to come.

You think so?

Absolutely! Life isn’t over. It’s a new chapter. And another chapter. A set of problems is just a new chapter.

.

I make noise with a chair on my side of the terrace so they know I am there, but it has no effect, the two women keep talking, so I abandon my comfy terrace to zigzag bridges crossing the Tiber.

I step inside out of habit and curiosity; every church has a relic, fragments of the true cross, bones, thorns, nails. What chance that they are real? There is Christ’s alligator suitcase retrieved from the Holy Land, there is Christ’s hairdryer, and his first report card signed by Mary.

.

On the terrace Mary the nervous woman says, In the old days I’d talk to men. Now I hold back.

Her more confident friend says, You’ve forgotten who you are.

I lost that. You understand?

Absolutely! What if he knew you were looking for someone new. I’d be interested in his reaction. I’d be very interested.

Maybe we’ll meet some Italian men!

.

Ray-Ray says to me, “I hear you’re running for Pope. Very cool. If there’s an interview, just remember he’s human, he puts his pants on one leg at a time.”

Ray-Ray, so tall and smiling, has a girlfriend and a baby waiting back in Canada, but in Italy he’s on a quest for an Italian woman, even asking the Spanish woman for advice.

“Where can I meet them? What do Italian women like, what should I say?”

“It will not happen,” she says, “they live in another world. My apologies, but you must be Italian to seduce.” Ray-Ray has a few words of Chinese, but little Italian.

“One leg at a time,” she says, “yes, I understand such a motivational concept, but does a Pope even own pants?”

“He probably wears sweat pants at home,” says Ray-Ray, “you know, to chillax, eat chips and watch Euro Cup on the boob tube. But the man’s from Dusseldorf or somewhere. So what team does the Pope pull for? He’s deep in this crazy-ass palace in Italy, but, really, the man’s from Germany, right? And he’s got these Swiss Guard dudes, who do they pull for?”

“Is there a Swiss team in the Euro Cup?”

“The Swiss Cuckoos?”

“The Swiss Army Knives?”

“Ye Gods,” mutters Father Silas shaking his head while enjoying cake and custard.

South Africa is killing Italy in the Euro Cup; Angelo and the girls with beehive hair grimace as one. The goalie moves the wrong way with his ski gloves out-stretched. Italy has a gifted team, but they seem jinxed, they lose every match. For the locals this is heart-breaking and suspicious: are the matches fixed?

Angelo holds one hand up high: “How the team should play,” he says. Then a hand low: “How they are playing instead.”

As a child in Nigeria Ray-Ray went to old style British schools, obeyed a headmaster, wore school uniforms in the Nigerian heat. I try to imagine him in a blazer. Later he may try to kill himself in the Don Valley, but how can our group know that?

Ray-Ray says to the Spanish woman, “Did you know the Etruscan language was never deciphered?”

“That’s really a shame,” she says.

Ray-Ray keeps saying that he was a celebrity in China, the girls on campus loved him, flocked to him, thinking he must be an NBA star because he was so tall. But he is not so well loved in Italy. In the hotel Ray-Ray doggedly pursues the chambermaids room to room, his big wolf teeth in a grin.

“How you doing today, ladies?”

The chambermaids’ boss, a severe Aryan looking woman, shoos the towering Ray-Ray away from her staff. “Go! Go! Let them do their work!” And we smile at the ribald drawing room spectacle.

But what of my gaze, and my crush on Irena, our Croatian chambermaid? Am I so different than Ray-Ray? Every day I speak to Irena on the stairs or when she knocks on the door of my room to ask if I need my room cleaned.

Irena gently scolds me in the hall: “You should not walk about in bare feet! You might step on broken glass! You are a free spirit. It is America.”

“It is not America.”

I delay wearing socks as long as possible, not to upset Irena the chambermaid, but because in bare feet the day remains somehow mine, I feel the chains when I have to don socks and shoes and move out into the world to take care of something dubious or pay money to someone when I’d rather not pay. When I get in the door I can’t wait to peel off shoes and socks, especially in this hot climate. And what chance of stepping on glass when Irena guards our sparkling halls? Being scolded by Irena is enjoyable. She first showed me the long route to my rooftop room. Why do I feel my pursuit of her is not base, but is high minded, a noble romantic quest? “It is Canada.”

.

Marco the intern laughs about the hotel’s Croatian chambermaids. Three women were washing a floor and Marco had to get in the room for inventory, so he took off his shoes to tiptoe past. They were incensed; the clean wet floor should be made dirty rather than Marco take off his shoes. A man should just walk through.

“When I had to move out of my room and stay with the chambermaids I made my own bed every morning, but they would unmake it and make it their way. They are still very old world.”

.

On my way out of my room one fine morning I see Irena making up the beds next door, in what I think of as the sex room, as this room is used by so many mysterious couples. Irena pauses by the bed, looks over.

“Do you need your room made up?”

“No, thank you. My room is fine.”

She asks me every day and I have the same reply. I have everything I need. Grazie.

You are lucky, she may say. That is the usual extent of our talk. But today she stops her work, today she wants to chat.

“You are wearing shoes today,” she notes with approval. “You are from Canada,” she says, “what is it you do in Canada? What is life like there?”

She knows some Croatians who like Canada. She says, “Canada has more interest in culture. Here in Italy it is all business.”

“It is?” I’m surprised.

“Here it is who you know. Want anything done? You need a friend, a connection. And if you have no friends? Nothing can be done for you.”

“I think of North America as all business. With Italy I think of art and culture.”

“No, no. Clearly it is the other way around.”

Now I’m puzzled. Irena tells me of her home in Croatia, the hills of white stone above the sea, she says in Croatia there are mountains, but not too high, they are just perfect. Her town once a Roman colony and now she is drawn to Rome, her town once a key port in the salt trade, but now its beaches are covered with roasting Germans, the Germans are everywhere, the EU accomplishing what Hitler could not.

Irena says, “I’d like to move to London and go to school there, but it’s hard.”

Irena has been working in Rome two years to save her pennies. London a magnet for her, but London is so expensive and school in England is so dear, thousands and thousands of pounds Sterling. She worries, she worries about the crash of the Euro and the terrible economy and the backlash in Rome and Athens and Madrid and she sees the TV news of arson and riots and jobless males battling police and attacking foreigners (do we have that in common, Irena, we are both foreign?) She is an immigrant, as were my parents, but her hill town is close to Italy, she did not need to step in a sinking boat, she rode to Italy by fast train.

Irena says she worries that what is happening elsewhere is sure to spread here and become far worse. Greece is a disaster, Spain, Tunisia, Libya, Syria in rubble, Iraq in convulsions.

“It’s not over yet,” she says, “on the contrary, it is just the beginning.”

She has worries and hopes, Irena seems impossibly nice. She asks where else I’m going and I mention Napoli and Pompeii.

“Ah, Capri,” she says dreamily. “And you must go to Elba. Though Napoli has the best food. It is the best city.”

I wonder if Irena lives and works in Italy legally, but can’t bring myself to ask. Irena has three languages and I have none. I heard her speaking Croatian and the language sounded like jagged Russian colliding with musical Italian. How long must Irena clean tile floors in Rome, work in a hotel and save a few Euro to put herself through school? She has no iPhone or tablet, no college student pub-crawls, no fast Bimmer or fake and bake tan, no Mom and Dad paying the credit card for a trip to the capitals of Europe.

Irena served and fed Marco, the hotel’s American intern when he was kicked out of his room. The hotel was over-booked, desperate for a room, so for a few days he was farmed out to the apartment shared by several Croatian chambermaids. A male guest in their home was not allowed to lift a finger, they cooked full meals and fed him plums from a mother’s garden in Croatia, plums a storm-cloud purple, taut yet dripping sweetly with juice, and sliced wrinkled apples that tasted like summer wine, as if the apples were ready to ferment. The young chambermaids treated him like a lord.

Irena’s stern blonde boss bursts out of the coffin-sized elevator, an unwelcome genie with dyed hair. The woman stares, suspicious of a shirker, suspicious of what I am after. Irena’s face alters, eyes scared, and she scampers back to cleaning the sex room.

Sometimes I feel like an exact saint of restraint, sometime I worry I possess the virtues of a dog running loose. At times I’ve been called a dog, but my mien leans more to milquetoast, surely I am more custard than canine. Galloping miles of halls and stairs to the Roman street (I don’t use the elevator), I hope that Irena’s Aryan boss won’t make trouble because she spoke to me. But I am happy Irena wanted to chat with me about her future life in the U.K.

.

A sickle moon hangs over the curved brick portal arch, moon and brick permanent fixtures both. And statues everywhere in Rome, long lines of anemic statues peopling rooftops, huge armies of silhouettes and future suicides crowding ledges, arms spread as if losing their balance or to leap from the ledge and get air in their beards, fly off and shudder like shaky kites around the white columns and spires and tourist piazzas.

I stare at chalk-white eyeless statues and older Italians in the subway car stare baldly at Tamika’s dark round face and wire-rim glasses and dainty dreads. They are not shy about staring wide-eyed, as if Tamika is some amazing piece of furniture perched beside me on a subway seat.

Tamika is super-shy and doesn’t fit into the group of young drunks and Tamika is very aware of the open stares as we ride buses or the Metro. In Philly she fits in fine; in Rome her dark skin draws unwelcome attention, eyes on her.

Tamika asks me, “Do people stare at you here?”

“Not really.” I am becoming invisible and to be invisible has its uses.

Tamika tells me that she ate something that disagreed with her and warning she became sick on a moving public bus.

“I felt horrible, but I couldn’t get off in time. The driver stopped the bus and he called the police.”

“The driver called the police?”

“They took me off the bus and I sat for ages in the police station. No one seemed to be paying any attention, so after three or four hours I slowly stood up and walked out the door with some other people and came back and hid at the hotel. I get nervous when I see any police or a uniform.”

Shy Tamika the outlaw. Italy has an uneasy relationship with colour, with Africa, Africa once part of its old Roman Empire and still so close, a slow boat-ride away from Sicily or the Italian island of Lampedusa far to the south where refugees swim to shore at this exact moment or they fail to swim to shore.

.

Some citizens in northern Italy prefer the north, would like to be part of Switzerland or Austria or Friuli, Venice wants to be an independent serene republic. Italian cousins in the south are seen as uncouth, un-north, they are Terroni, of the earth, swarthy peasants, lazy, corrupt, brutish, violent, invaded and tainted by Arabs and Moors and Algerians, by heated kingdoms of darker blood, by invasion after invasion.

Men ask Tamika, Are you Africano or Americano? They want to be sure.

Father Silas surprises us, saying, “Some Italian men have a fetish for black prostitutes.”

“A fetish? North Africa? West Africa?”

“I really can’t say, it’s not my fetish.”

.

“It’s not that I’ve been cold to him.”

The two woman talk on the next terrace and I imagine my wife saying similar words to her best friend over a glass of shiraz, adjusting decades of memories. To hear this is depressing.

“You ask yourself what happened to all those years.”

The years of connections and cities and good times don’t alter or disappear. But now those years are different to my wife, now tainted, though not to me. The women talking on the next terrace are a vocal reminder of what I’ve done wrong and how I will be misunderstood and maligned over a glass of shiraz, perhaps at this very moment.

“This new therapist, he lets me come to my senses, he doesn’t tell me.”

“I like the advice this doctor gives you.”

“Is it out of fear I’m doing this or out of love?”

“You do what you have to do.”

“I don’t want my kids to be vulnerable. Damaged people gravitate to someone like, to damaged people. I can empower my two children by standing on my own two feet. Or they’ll step into the exact same scenario. It’s a valuable lesson.”

“You know in your heart you did everything you could.”

Don’t the women know that I’m on my side of the trellis and vines, that I hear every word and sigh? I make noises on my terrace to alert them, but they are like oblivious shoppers who block the whole aisle with their carts, no one else exists.

“What if he came back? He’s not open, he’s not going to be expressive or lively or please me. He can’t find it in himself to be happy.”

“Can’t go down that road. Tell the kids when they’re older.”

“If I’m giving 150 per cent and he’s giving 80, it ain’t gonna work. Is that flame too high?”

“I don’t think so.”

“That fire worries me. Should we get some water?”

“It’s citronella. It smells nice. Ah, this is the life. Shopping in Rome.”

“Can we put it out?”

“Okay, okay. Feel better?”

“I do.”

.

Jesus, I think, let the stupid fire burn. I’ve lost my euphoric mood under the perfect cupola of chapel stars.

So once more into Rome I wander footsore, that one church on the edge, marble underfoot, tombs underfoot, reading graffiti, stepping over graves, over a lost city. Eve and I gaze at The Conversion of Saint Paul, but the canvas is so dark for an epiphany, it seems more the reverse of an epiphany, I see no light or illumination.

Saints line every rooftop and I pass the spot where the dead rat has been resting every day on cobblestones and when I wander back the two women still talk on the next terrace. Like me, like the woman from Iraq, these two women on a terrace so dedicated to their dead country.

.

“I told him wish you were here, she says. Why did I say that?”

“Because that’s how you feel. Mary, you’re allowed your emotions.”

“If he was here he’d know every temple where Caesar was stabbed. I think women a generation or two back were stronger.”

“Hey, we’re two powerful women — we put out the fire.”

“Safety first, ha!”

“This is fun. More vino?!”

“We are having fun.”

“Be grateful for small things. The here and now is important.”

“You’re wise.”

“Life isn’t over. It’s a new chapter. Life is a book. And each chapter….”

“See in a marriage…well…he betrayed me. But I’m more angry about the car than that woman.”

“Tell him you’re looking for someone. Did you do that before?”

“Fool around? No.”

“To grow.”

“No.”

“I did, I went to someone else. I felt those feelings. It scares me that I don’t care. Is it because I’ve dealt with it? It’s wonderful to feel that close to someone. If I stumbled across her in a social setting, what does she look like, I don’t care. It’s almost creepy. It is creepy, a creepy creepy feeling. Every day I wake up and expect it to change.”

“The Mole called me back.”

“Who? Not him.”

“Turned me down, but he called me back.”

“You’re better off without him.”

.

The woman’s last words make me wonder: in the long run, am I better off without Natasha? I resist, but I need to believe this, need to take it in like an arthroscope to the knee.

Something in me can’t accept the finality, some part of me still wishes for contact, to hear of Natasha’s mother and father, the farm, her sisters. “My dad’s youngest brother died, only 62; my poor dad, such a shock for him. My crazy sister is okay, but her boyfriend bonked her on the head with his laptop and she’s depressed a bit.”

And I want to tell Natasha all my Italian news, I feel a wave at times, a physical command: lift the phone, click Reply on her last email. But I have decided: no more.

It’s difficult, as we were so comfortable with each other; how to find that lost empire again in the stone mountains? It seems impossible. The anatomy of desire and the anatomy of loss – I have them mixed up in my sun-burnt head. Brushing my right ear is the fever song of mosquitoes, then a mosquito frittering inside my ear, wanting my brain. I smack my own head hard, then cry out, OW! And Eve laughs at me: is such slapstick exactly what this mosquito aims for as evening entertainment? Like me, the mosquito has a soft spot for the Three Stooges. Rome’s hills and marble temples built above a marsh and winter mosquitoes felled an emperor. In Trogir I leapt off a water-taxi to see a Norman fortress in palm trees and walked Malarjia Park. In Rome we will devour delicious blood oranges and pray to Madonna della Febbre, the protectress of victims of malaria.

.

At night in the hotel stairwell I bump into a thin blind man. The blind man is shirtless and wields a long white cane, a slim stick, a pilgrim of sorts. His pale wonky eyes aim into deep space.

“I’m above you on the steps,” I say.

“Are you with that group?” His voice is assertive, angry about noise in our hotel. Would I be so confident if I might fall down an open stairway?

He says, “I have a wife and a two year old trying to sleep. Can you tell them to stop chit-chatting?”

He may mean a noisy group up on the roof. I don’t know them, but I lie to the blind man, saying I will pass on his message. Is it more of a sin to lie to a blind person? Or is the sin pretty much the same?

.

Eve and I are crossing manic streets like expat experts, we’re leveraging complex transactions in fruit market bedlam. When was it I met the exiled woman from Iraq in a supermercato? She told me later that I did something and she knew she could trust me, she told me that she can read people, was trained in it.

Was it posture, I wondered, how I clasped my hands?

She wouldn’t tell me what it was, but it was enough for her to believe in me.

I had no idea what I would learn about her family, her fiancé. At the time she was simply someone interesting I met by chance, one of Iraq’s numerous exiles, Iraq coming to pieces and so many forced to become gypsies, wandering like brimstone butterflies, the first to appear after winter.

She worked in a hospital in Jordan after fleeing Iraq, liked her job and the people and the dialect was similar, but Jordan was overwhelmed by refugees from Iraq. Every month she had to make her way to a police station and pay a monthly fee to stay legally in Jordan. The fee rose every month until it was too high for her to pay and she had to leave her job and had to leave Jordan and look for work in Italy.

She does not drink, is devout, well-schooled in the Koran, but she does not wear traditional garb, does not wear robes or a veil. She can look very western in stylish jeans, makeup, nail polish, even a Mickey Mouse T-shirt if she is in a happy mood.

The woman from Iraq told me her father had kidney problems, she worried about him. She said to me with a serious face, “Drink only water when you wake up and cleanse your kidneys.” No one else speaks to me quite like this. I enjoyed such times. She was always very clean, concerned with health and hygiene. At one café she wouldn’t sit on the seat cushions because they seemed dirty and she was used to better.

I bought her tea from Ceylon, Akbar big leaf, and one afternoon over tea I guessed her age.

“How did you know?”

I said I liked the henna tint in her hair and she asked, “How you know that word?”

“I know some things.”

Much of what I said seemed to surprise her. I told her about Natasha and she did not approve. “So she left after causing trouble with your marriage?”

“It’s not that simple.”

“No?”

She showed me the ring her brother gave her years ago. “He loves me. He is very handsome. And in Iraq it is real gold, 21 karat, not like here, 10 or 11. In the Middle East men don’t wear gold. Only women. Men don’t have earrings like here. If men wear jewelry, or a lot of gold, we think, eh, no.”

She looks at my hand. “There are no rings on your fingers? All those years, did your wife not give you a ring in all those years?”

.

The women’s voices continue on the next terrace.

“I fall for people. You understand? I fell into that trap.”

“Are you mad at me? What I said about the Mole?”

“He was nice. He’s ok. He had the Asian wife. He did seem interested in me.”

“He’s a microbe, a creepy little creep. He had an affair with the cleaner, can you imagine, creepy, on the desk.”

“No.”

“Yes. He’s a pervert. She got pregnant.”

“Maybe that’s why he was so hot and heavy to get a vasectomy.”

“He’s a perv. He has to send her cheques and his other wife has to get up at 5 a.m. to catch a bus and work at a factory.”

“She probably has no background.”

“Treat your spouse like that. It’s unbelievable. A perv.”

.

I listen to the women and think, Now I have joined the club of those sending cheques, joined the club of those termed a perv.

The woman from Iraq says, “Everyone I meet here, divorced, separated, divorced, separated. I think our system is better.” She may have a point. My drunken question to popular opinion: Why does the phrase “night falls on Rome” sound cool, but “morning falls on Rome” sounds clunky and wrong?

She doesn’t drink, but young males stagger our hotel halls shouting, MAKE SOME NOISE! Rome has no history, Rome is a drinking binge with no parents to harass them. They lug huge jugs of rotgut wine, yelling Yo Yo Yo Yo!

Young and loose and full of juice, drunk with what seems possible. Their shop has not yet been bombed to rubble, to molecules.

In the Roman night someone is insisting over and over that she is not a hollaback girl. My high room is well removed from the inebriated and industrious fray, but poor Tamika’s hallway is the epicenter of several open-door party rooms.

Eve walks by bent to her tiny clamshell phone, her face serious, saying, “She told me three of the drugs she was on.”

Tamika says, “I can’t get any sleep with their drunken racket.”

Father Silas says, “I’ll see what I can do,” and walks over to a noisy open door.

“You ain’t my daddy,” yells a drunken female voice inside, “and you sure ain’t ….” And then the voice trails off, seemingly stumped, and we all wonder: what else is he ain’t?

Tamika does not like the drunkards, Tamika a lone wolf roaming Rome while the others seem blind to the ancient city, see Europe as a hotel, an outlet shop, a humongous nightclub. They are the same age as Tamika, but she dismisses them with a world-weary wave.

“It’s so awesome here in Rome, but all they do is complain about everything, they bitch about the food, bitch about their room, bitch about walking through amazing cathedrals. They complain if they have to walk uphill! They bitch about having to look at Bernini’s marble and paintings by Caravaggio.”

Tamika mimics their voices: “It’s not fair! You can’t tell me what to do. This is boring. I’m hungry.” Tamika pauses for breath. “Rome is not boring, they’re boring.”

From my backpack I dig out a tiny sealed bag from my days in a loud band: the baggie is not drugs, but a packet of disposable foam earplugs for Tamika. Eve asks for some as well, worth a try to help her sleep and she is wary of depending on sleeping pills.

Tamika takes the earplugs a skeptical look on her face, and eases the door closed on the drunken mayhem. She longs for sleep.

.

My cousin Eve has an uneasy relationship with sleep, uneasy with Morpheus and Hypnos, the father and son team running our sleep and dreams. I never know if she is awake or asleep, she has a night language, uses her hands to make a point or ask a question, wakes up laughing. It’s odd to watch. Eve dreamt the two of us were trying to find our way out of a city-sized department store and I fell down an open elevator shaft.

“People were running down stairwells to find you. Is that a 9/11 dream?”

Is the blind man’s sleep a steep grey cinema? Has he ever seen stars at night? Can you imagine colours and faces and fields in your dreams if you are born blind and have yet to see colour or a face? Can you dream light if you don’t know light? When the blind man is in a better mood I must ask him.

To shutter my own eyes at night seems not always to deliver quietude; my sleep chaotic, unnerving, festive. I close my eyes to a strange movie-house in my head, fragments and half-lit clips, an unseen projector constantly grinding. A huge cast and the footage never stops. I have no idea where these night films come from, but I like them.

.

“Someone called him, did you hear of the bomb downtown. I begged him not to go.”

The woman from Iraq told me about her fiancé, though she did not tell me this part right away, it took her some time to get to the chapter of her fiancé.

“His business was in the bombed building, he wanted to see if his shop was hit. Can’t you wait? I had a bad feeling, I pleaded with him.”

Sorry, sweet one, he said, I must go see the damage; perhaps his shop would be spared, God willing. His shop was his livelihood, his hope, their future, her fiancé was worried and he drove into town to see the damage.

The second bomb exploded later, timed to kill those who came to walk the rubble of the first bomb. The second bomb exploded and her fiancé vanished and she was a widow without yet marrying. As Trotsky said, You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.

“He was good to me,” she stated calmly, “he was modern, he told my parents when asking for my hand that he didn’t mind if I wanted to go to school or have a career.” The bomb was only months before, but she stared off speaking flatly. It happened to someone else a long time ago in a world that no longer exists.

.

Thursday at dawn our art group rises grumpily to inspect the Sistine Chapel. Father Silas has a connection, he knows an ancient Irish monsignor who arranges a select viewing, but we must arrive very early, before the mad throngs block the front of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Eve and Tamika crave more sleep and the party animals cradle monstrous hangovers from their dubious cooking wine. For a few cents more decent plonk can be had, but they scoop up huge jugs of cheap cooking wine, amazed by bargain prices, but this is stuff the Romans don’t drink. At dawn they feel the hurt big time, at dawn they can barely move, can barely text or kill aliens.

In my arms I once carried my dead dog from the street where it had been hit by a driver who did not stop: my dog’s beautiful brown eyes lost their light to a machine, the brown eyes had no depth, no engagement, no awareness. Some in the group have that dead canine look as we shuffle down the block to Michelangelo and the vaulted ceilings of Sistine Chapel.

My head! Man, why does this asshole make us go out so fucking early? Who wants to see some stupid Listerine chapel? Dude’s seriously harshing my mellow. And we’re missing the coolest Shark Week like ever. Got any Advil? Man, I can’t deal with fizzy water, going to hurl.

Father Silas hates alcohol and some suspect he has made us rise early to punish those with piercing hangovers. He reacts strangely when I happily tell Tamika that Eve and I found an “Italian American-style Irish pub” called Fairy Tales of New York, a great little underground bar.

“American and Irish and Italian?” asks Tamika, interested. “What was that like?”

Before I can answer Tamika, Father Silas gets right in my grill.

“A place for American college students to get DRONK!” he shouts, his big reddening face in my face.

I want to say the pleasant arched cellar is not for drunken college students, but he won’t give me a chance. Everyone I meet in the cellar is Italian, lives in the neighbourhood, and the young musicians are local. But Father Silas hates any mention of pubs and pub-crawls and Rome is crawling with pub crawls, posters and ads everywhere; Father Silas is furious when he spots Ray-Ray in a souvenir T shirt from a pub-crawl that reads APPRENTICE ALCOHOLIC.

Ray-Ray complains to Eve. “Man, why does he get so mad like that?” Ray-Ray says, “I’m not a child. I can travel and check into a hotel, he’d be surprised. I can do all sorts of things.” The younger people in the art group hate it when he lectures them on how to behave in Italy.

.

Father Silas may not win a popularity contest, but he finagles us past the giant lineups in front of St Peter’s, skipping mobs and security checks; his Irish connection in the palace of Popes pays off. As early-birds we have time to check out the Sistine Chapel before the crowds arrive. How many times have I joked about some half-ass project, Don’t worry, it’s not the Sistine chapel. Now it’s the real article, now it is the Sistine Chapel!

Father Silas expertly guides our eyes through each brushstroke and painted image on the ceiling, nude bodies and fresco skies of pale pink, robin egg blue, pale canary yellow, Noah drunk and disgraced and martyrs and mild saints flung about hallucinatory heavens floating in this chamber. I love it. Grotesque figures and prophets lean out from high dizzy corners and sinners pulled to hell in this ecstatic artifice.

Noah a drunk! News to me.

Don’t let Father Silas know, says Eve.

The guards yell at us, No fo-to!

A young German backpacking couple elbows me, pushing past me to cram closer to Father Silas and hang on every word; they are not in our group, but they are eager for Father Silas’s narrative of the Sack of Rome in 1527; our group couldn’t care if the Sack of Rome is in five minutes.

Eve nudges me, signals with her eyes at a bench where some of our disgruntled comrades perch: one art lover cradles his pained head in open hands, one holds his giant Dr. Dre headphones tight, one poor soul manages to tap out a text. In the Sistine Chapel they are all looking down! I will say this once and then let it go: the fucking Sistine Chapel and they can’t see, can’t lift their eyes to Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment, blind to the arches and lunettes and miracles hovering above their dehydrated heads, blind to treasures floating over their trauma brains.

Above us God divides light from darkness and we linger in the centre of the chapel, Father Silas ecstatic, the longest visit he’s ever had here. But as the room fills with travelers, guards spring up to move the crowd along the marble, to herd us to the exit.

“Keep moving. No fo-to.” Does the blind man know the chapel? “Keep moving! No fo-to. Keep moving! No fo-to.”

A woman from Delaware asks me, “Where is Noah?” And I have the answer! I show her the ark and his drunkenness and we chat easily, she charms me, looking me in the eye – how to describe that permission to engage her eye, the face, that magnetic connection? But her tour group is gone from the tidal room and she worries she has lost them.

Bye! she says hurriedly, eyes still on my eyes. Very nice talking to you, she says.

I want to say more: woman from Delaware, you seem important. But what to say quickly that doesn’t seem lame? I fail to utter key words and she vanishes from sight. Sometimes I feel my own mind staring at me and judging like a separate person. Delaware: I’m picturing a river, a green valley.

.

In the Vatican cafe Ray-Ray buys three sandwiches and three drinks and thirty Euro vanish in seconds; Ray-Ray puts it on plastic, does this over and over, Ray-Ray is always hungry.

A button on his tote bag says, I was Raised by a Pack of Wild Corn Dogs. “Does the Vatican sell corn dogs? I’d kill for a corn dog.”

I don’t know if the Vatican has corn dogs. I will return from my travels to be murdered in the bath. It is the 40th anniversary of the White Album; the Osservatore Romano says that the Vatican forgives John Lennon his “boast” that the Beatles were bigger than Jesus.

“Weird to drink beer in the Vatican.”

My parents loved the church and hated the Beatles. I am going to get me religion, maybe I’ll start a church, the church of cold toast. Natasha likes cold toast and cold butter, as I do. No one else likes cold toast. It’s a sign, she sank her nails into me, haunts me still. Like Pompeii after the volcano, the shore altered.

.

Through marble halls and chambers we find our way and stumble outside to battle sunlight in our slit eyes, we are in the vast pillared piazza in front of St Peter’s Basilica, the floating dome, the silver spaceship, the mothership and its rows of myriad Doric pillars moving out like great arms enclosing a flat open space larger than a football field.

.

This is not the way we entered; this morning we slipped in the north side, and now we move under the church of churches, the rock of Peter. Byron admired this view, this architectural marvel, Melville stood here, Goethe, Dickens, Dostoevsky, Jethro Tull.

“Are there any zombies in Rome? Yeah, zombies in the Vatican! That’d be a very cool movie.”

Ray-Ray yells “HEY” and runs across the space to question an Italian man who is missing one leg and has an amazing comb-over, his hairdo a monument to tenacity.

“Hey man, is it true about phantom limbs, that you get an itch in the limb that’s not there anymore?”

Non capisco. He doesn’t understand English.

In the endless white light, in the corner of vision, a bear cub gallops through the forest of pillars. The bear must be panicked, but it looks very cute: dark fur, a pale brown muzzle, outsize ears and that rolling stiff-legged lope past our hungover group, past Saint Peter’s, and barreling toward the sidewalk men selling leather purses and sunglasses.

“How did a bear get here in the city?” asks Eve.

Is there a gypsy circus camped in Trastevere or the Piazelle del Gianicolo? The poor animal swiftly crosses a road, speeds down a narrow medieval passage and I can’t see it anymore. People scatter before the bear cub, but some follow behind attempting shaky photos and videos. A tiny blue police car joins the chase and when the men selling sunglasses see the police car, they gather up their squares of cloth and footstools and vanish, a form of magic.

“Oh shit, where’s my iPhone?” calls out one of our group, half of a star-crossed tragic couple who have fallen for each other on the trip, but are betrothed to others back home. They spend much time in Rome pacing and staring at each other and exaggeratedly sighing like silent film stars. “Did someone steal it? I put it down for like five seconds max. My mother’s going to freak!”

In Italy eyes are on us, waiting for the moment when we put down our laptop or briefly ignore our camera on the table. The thieves love us.

Eve says she was mugged for her phone in Chile: she laughs telling us, says the man asked for her phone, looked at it, an old clamshell with a duct tape hinge, and handed it back to her, her phone not worth stealing.

“What’s it like to not have a phone?” They ask me this with genuine curiosity.

Discarded phone cards litter the ground. They are so afraid to not be connected; everyone staring at a tiny screen, that slow zombie walk, zombies in Rome.

Our hungover group walks away from the mothership’s giant field of pillars. Taking our place, a new batch of amiable tourists line up to display their girth and sunglasses; we are all part of a giant art installation, the pure products of America abroad, trodding leather and considering miracles in marble and wondering about beer and lunch and dinner menus with no inkling that a cute bear cub rambled past us moments ago.

Ray-Ray stops me: “What kind of pants is this?”

He’s studying a woman swishing past in gold harem-pants; her walk has a pronounced twitch, her pants moving about her like shimmering drapes.

“Looks like MC Hammer.”

“Who?”

“You can’t touch this.”

“Touch what?” He looks suspicious; what am I talking about?

With the harem-pants woman we try our limited Italian. Dove un internet café?

There follow many speedy sentences and in seconds I’m lost.

Wait, non capisco. Holdo, signora, parla lentamente per favore, lentamente, please speak slowly, I am a foreign simpleton in your speedy empires of talk. Our group did not invent stupidity, but we are the latest visible practitioners.

.

My cousin Eve leans conspiratorially toward Tamika and says, “Those Italian men on the street! Their eyes, they look right into your soul.”

Tamika mutters, “It’s not your soul they are after.”

Amore, amore. Look at the eyes here, eyes like slow sunsets and foxfire and Friar’s lantern, eyes like the feral cats in the temple ruins, diamond-eyed cats after rats.

My eyes roam the world too, looking for stars held in a cupola, looking for the right person, a person who likely does not exist, like my childhood guardian angel, an ideal that may lead only to disappointment. I’m not unlike the two women on the next terrace in that respect.

.

The promise of Rome and the promise of the Spanish blonde in the leafy hotel atrium, her adherence to smoke and water bottles; I work up my nerve for the question. And I never do this.

“Would you, um, care to go out for dinner?”

“No,” she says too quickly. “I’m having dinner with my friend when she gets off work.” So Elena was expecting the question and ready to say no. What is it like to believe in an anthem, I mean really belt it out?

I need a wee drink. The others keep working away on vats of sweet wine. In the laneway a few feet away a sweaty man with no shirt hits a motorcycle with a piece of wood, setting off a loud alarm. The man tosses the piece of wood and casually lights a smoke to wait for the resulting beneficial social interaction.

His hope: someone will approach and fight.

Our hope: he will go away.

All our tiny wretched hopes like cartoon thought balloons over each block of Rome, multiply these across the city street-map, across the wide world, all these hopeless little balloons of our hopes, like markers on a board game, like hotels on Expedia.

We are not always pleasant, but we all have our tiny hopes.

.

The blind man wanders the stairways in search of culprits and the women’s voices continue on the next terrace.

“I asked that nun for the time. In Italian.”

“We fit in.”

“We’re doing so well, we went right to the edge of our map!”

“No one would know we are tourists.”

.

Sun beats on our skin, leathers our lives of quiet desiccation, sun on lovely hours of fountain spray as Hotwire and Orbitz fight over my soul and then the strange lost look of my street before dawn.

Get some sleep behind scrolled blinds and rise late and the sun always there until it must enter the horizon like a burning airship and a million emails jetting out to everyone in the world say A Special Offer Just for YOU! and at dusk swallows circle and blur in a mosquito frenzy and in her famous T-shirt my cousin walks out in the garden of green parrots just before rains sweep in from some distant sea.

The Italian man has eyes. As do I. I resent him as cousins might.

“It’s so cozy here,” says Eve. “I love the sound of the rain.”

Night and the light on Eve’s face may change your mind about the world. I have to gaze, to compensate for the blind man who can’t see her. Behind the city a wall of rain like green glass, like some remnant of hurricane season. She climbed above me in the fig tree and I was allowed a vision of her muscled legs and beyond, I see Paris, I see France, I dream of her at the beach, half nude at the shore, her freckled skin so lovely, to live inside it, to kiss her in the eelgrass, light under the harbor swell like light inside a fountain, to see her at the sea where she is almost naked with strangers, but I never go with the group to the beach, it is too scorching or I am not inspired.

Perhaps I’m a winter person, a touch of winter in me always. I should drop everything and be a ski bum in the blue glaciers before they melt and vanish, I could work on the hill, work as a liftie putting skiers on the Angel chairlift.

Eve knows the mountains and resorts, says, “No, don’t quit your day job. Being a lift-operator is a killer on the back and people are always falling over and poking you with their ski poles. Definitely join a band. Chicks dig that.”

The lifties use shovels to level the snow where skiers load on the chairlift, like shoveling coal, and Eve says at shift’s end they’d set their ass down in the scoop shovels and race each other in shovels to the bar at the bottom of the mountain.

.

God is irritable, God recently gave up cigarettes. At our subway stop I let Eve and Tamika step out first, but the doors close hard on my arms as I step out just after them. Why do the subway doors attack me when I was so chivalrous? Perhaps the gears and sensors know something of my true nature, gods alive in our machines and devices. I must have offended the elders of the internet, a major disappointment to You Tube. I need to learn to love technology, must dab datum on me like cologne from a dollar store.

.

In the neighbourhood café Francesco knows our faces and gives us free morning coffee. Angelo, the aged hotel owner, joins us for a late breakfast. Eve picks up an espresso and an Italian newspaper.

“Tell me, Marco,” Angelo says to the American intern. “Is it true that Americans eat donuts for breakfast? That is wrong.” But for his breakfast Angelo fills a sweet croissant with whipped cream and chocolate Nutella.

Angelo says he used to know the Vatican crowd, but no more. I assume those men he knew are dead now (and there rose a pharaoh that did not know Angelo). He doesn’t look that old, but Marco says that Angelo is over eighty; he never stops working on his hotel, moving walls, refurbishing rooms, digging a cellar.

Eve and Tamika run off to a pro-choice rally gathering in front of Pope Rat’s place at St. Peter’s; Angelo finishes his whipped cream and Nutella and leaves; Marco lowers his voice to tell me of an old friend of Angelo’s at the hotel.

“The man paid me cash for three different rooms. Seventy years old if he’s a day. He books the rooms for four hours and I swear five different women showed up.”

.

I wonder if the noisome couple in the next room paid by the hour, the minute, or down to the second. Or hotel staff who know it to be free? Or was it Angelo’s old friend with his harem? Does his harem wear shimmering harem pants?

.

Every hotel, every guest house, every B&B, has offered me “an arrangement” to pay cash. No receipt, but the room costs much less. I find it hard to say no as it saves me so much, hundreds easily, perhaps thousands given enough weeks or months. Factor in millions of tourists wheeling luggage down Europe’s cobblestones and dropping cash only and one sees why lawmakers and accountants have such trouble chasing their cut of the haul. As a spoiled North American I am so used to plastic, but cash is king here and my best deals are off the books.

.

Marco’s work at the hotel has to do with the books; Marco’s task is to nudge the hotel into the computer age. The French woman still consults a huge old-fashioned ledger book with our names and reservations written by hand. Marco is setting up a computer. Businesses in Italy often need two sets of books; after Marco is done, will the hotel need two sets of computers?

God enriches, but cash is king, so we all must stash envelopes of cash, cash on my person or hidden in my room, more cash than I am comfortable carrying or hiding.

.

Eve’s purse was stolen from her hotel room a year before; she found a small footprint in a flowerpot on her balcony and her bag tossed to the next balcony. Luckily, the young thief missed Euros she had hidden in the WC. The art historian’s phone lifted as he walks a crowded street, a religion teacher’s wallet eased from his front pocket on the bus, a beatnik backpacker swarmed by children, turning and turning, a dizzy whirligig to keep their nimble fingers from his pack pockets, and a pink rental car stolen as a woman from Banff opened the car door for the first time, she possessed the car for seconds and it was gone.

.

Marco and Eve traveled to the police station to interpret for the hotel’s American family who lost a ring handed down from a great-grandmother, lost blown glass from Venice. A sweltering night, an open window or balcony door. The police type up a report, but what can they do, a waste of ink.

Who expects someone from the roof? In all corners of Europe such a complex economy dotes on our purloined phones and cameras and we oblige, we carry cash, wallets and laptops, and we deliver them to the thieves. How they long for us like lost lovers in their damp winter and each year we come back like the blossoms of spring.

.

Angelo had to sack an employee who lit rubbish on fire in a stairwell; the employee hated the guests, the noisy party animals, and he wanted to get off work early. So a fire against the exit door is the answer. Could he be the hotel thief? Or is it the blind man, bounding like a cat across the roof?

.

Father Silas tells our group a farmer’s daughter joke. And Natasha sent me email from her parents’ farm in northern B.C. Why did I not think of this all these years: Natasha is a farmer’s daughter. I broke off contact with the farmer’s daughter, for my own well-being, but every day I have a physical urge tell her what I see in Italy.

In Canada Natasha said we must stay in contact, an unbearable empty place if we stop talking, a huge hole in both our lives. She said those words, admirable thoughts. But in her life, in her distant city, she has someone there to turn to, to say she had a bad day, to say, He’s really upset, I just don’t know what to tell him. She can say to say to someone, Let’s go out for a drink, can say later, Hey, love you so much.

..

Irena the chambermaid greets me, Come ve? She does not ask, Come stai. Is she being formal with me as a hotel guest? Irena is always so friendly with me. Is she just as friendly with the others? I want her to like me. She wears cargo pants with numerous pockets to hold cleaning gear, waistband low on her belly from weighted pockets and pulled tight on her round rear. Irena’s shirt rides up as she cleans the room and I notice a puckered scar on her belly like a hieroglyph, a story scripted in a scar. In her supple hands a large sheet rises and settles as if on a breeze: her levitating art.

Come stai? I ask.

Sto male. She is sick. But she is working anyway. Maybe she caught whatever Ray-Ray had when he arrived from China. Some afternoons I see the chambermaids walk away from work in their street clothes, altered in their clothes, happy to be free on the sunny avenue, happy to be free of us.

“I hope you feel better,” I say. She nods.

Irena leaves the sex room, Eve leaves Italy like a merry sleepwalker, “Excuse me,” says Our Lady of Madrid, “I must go.” Soon all leave the city, the mountain frontiers, leave Europe’s stone quarters and catacombs, say goodbye to the orchards and marble excavations.

..

It seems so long ago that Natasha phoned after silence to say there was someone else. I knew something was wrong, but did not know what. I was married to the sound of her voice, talking to each other when she was almost asleep, part of something beautiful and spooky and rare and rich, but part of nothing now, and another woman in a doorway or an airport says, I’d hate to lose touch with you, you know I love you in so many ways, who says, It’s been wonderful. My half-buried past, my layered Pompeii, my quiet buried city.

That day my faith was tested. Phil Ochs in exile from Ohio, kicked out of Dylan’s car, no more songs and the rope on the pipe beckoning. The snake handler’s look of disbelief as he died in his own church, as he recalibrated his idea of being exempt from the fang.

I KNOW I AM NOT SPECIAL: I must repeat this until it sinks into my head like a spike into a rotten log. Exiled from dopamine, from the snowshoes of yesteryear, I tape a piece of white paper to a mirror: For sleep, riches and health to be truly enjoyed, they must be interrupted.

.

On a map I showed her Canada, showed the woman from Iraq where I grew up. She is well educated, but has rarely seen a map with Canada. And America there right below Canada.

“They have has so much space; why did they want to invade our country when they have so much land?” She peers at the map with utter puzzlement.

The billion dollar question: why did Bush and cohorts invade the wrong country? Oil an easy answer or they got their Auto Association maps mixed up. Or rumours say the invasion was revenge for an earlier plot by Hussein to kill Dubya’s father, George Bush, Senior.

“Bush is in town; you could ask him.”

“Bush is here? Where? I’ll go see him. Did you see him smiling on the aircraft carrier, he was so happy while we suffer. Bush is always talking of terror. My brother is not a terrorist. I am not a terrorist, I want to hurt no one. He has killed more than anyone else in the world. Will someone hunt down Bush and hang him on a rope?”

The woman from Iraq is very charitable, she is not anti-American, has relatives in Chicago and wonders about moving to live there.

“I hate no one,” she says, “but I hate that man. When they threw a shoe at Bush, I was glad.”

I do wonder about Bush, what he really thinks. “Did you ever see your Mustang again?”

“Oh no, nothing was left.”

Blow upon blow, her pleasant world dismantled by this man Bush, her fast American car transformed into a tin can, her brother kidnapped and dumped in the desert in plastic cuffs, her mother going mad with worry, her fiancé dead in the rubble, her happy life stolen by a thief. And the banner on the aircraft carrier: Mission Accomplished. After meeting her, I swear I’ll never complain again.

Her mother misses her bright laughter in the house, now the house is quiet, but for the noisy generator running outside the house; the power off and on since the invasion, so they must run a generator in the yard.

“I was always laughing then,” she says. “Now I only laugh with you.” And somehow we do laugh a lot. Our odd connection.

She says her mother needs to go to the hospital, but the power grid is so damaged that doctors are afraid to start any complicated surgery for fear the lights will go dark while a patient is cut open. She grew up in a prosperous, stable country, her father a professor, but now it is too dangerous for him to leave his home and risk the roadblocks where someone in a mask may execute you if you say the wrong word or drive the wrong part of the city.

She misses driving her car in Baghdad.

“Was your Mustang fast?”

“Oh yes. I’m not a crazy driver, but on the highway one must go fast.”

Marco convinces Angelo to lend me a two-door Fiat so I can take her for a spin and let her drive a car once more. I am nervous in Rome’s traffic. Sniffing Rome’s oily exhaust, she claims the petrol in Iraq is so pure that her car’s exhaust was sweet as perfume. Before the war every road was brightly lit and the roads smooth and broad, not so narrow as here.

“Summer must be hot in the desert. You must need air conditioning.”

“Desert? Iraq is not desert. There is a river, how can that be desert? There are plants, a hundred varieties of dates and olives, such flavours.” She is offended. “Iraq was a great civilization. Why do you say desert?”

Sorry, but on TV with the rolling tanks and dust it looks like desert. When her car was too hot in the Baghdad sun she kept a special aerosol spray in her purse to cool the hot metal so she could touch the car door without burning her hand.

Sipping leafy tea, we chat and laugh and by accident I discover my power over her: if I reach out in conversation, touch her shoulder or neck, the woman from Iraq swoons, falls into some half-awake state, not used to touch from a male who is not a cousin or betrothed.

I ask, Has this happened with anyone else?

No one else has touched me, but you and my fiancé. How you do that?

I don’t know; it’s never happened before.

Please don’t right now, I want to go out, I don’t want to be sleepy.

I touch her and her knees buckle, but she acts as if it is normal to have such power. She casually asks me to be careful. Yes, I will be careful. I have the strangest life.

She asks me, “In Chicago, are there many blacks? I’ve heard there is work in Chicago, but it has many blacks.” She worries about blacks. “They scare me,” she confides.

“Winters can be cold in the Windy City,” I say, “and you’re used to the heat.”

“Yes,” she says, “I don’t know how you go outside in that cold. You whites are tough!”

I get an inordinate kick out of being called a white. I put my arm by her arm and her skin is lighter than the skin on my tanned arm.

The woman from Iraq jumps at any noise, even the sound of feet running on stairs in her building. I strum a quiet Townes Van Zandt song on guitar and she says, “That’s nice, soft music.” She can’t listen to loud rock or rap, she can’t take bright light, must wear her big sunglasses.

At night she wakes from nightmares, has a frightening nightmare immediately after telling me the story of her fiancé and his bombed shop, her eyes closed in sleep she relieves the scene and I feel guilty for bringing on the nightmare. Any noise in a room above, a shoe dropping or a door slamming and she jumps in panic. I’m no physician, but these seem classic symptoms of trauma. The young American soldier in the graveyard may suffer from the same set of ailments, the war that always follows the war.

Odd that I meet both in Italy, two brains creased slightly by trauma, two brains moving through train stations of beautiful flowering vines and thuggish teens.

I heard this mother and daughter weep on the phone when a connection worked. Often her phone rang briefly and then went dead. I bought her time at a grubby internet café. She told her mother all was well in Rome, she didn’t want her mother to worry.

We’ll talk soon, she said to her mother, God willing. She often ends sentences with this careful phrase: God willing.

“If there is a God,” I commented once.

“No if!” she said. “No if. Believe me, there is a God.”

But is it the same God George Bush believes in?

She has such faith in God, that God will look after her, but she must sell the gold ring from her handsome brother who loves her, she must enquire into jewelry or coin shops. She can’t understand why this has happened, her father trapped in his eerie house, the old land of Persia laid low, his daughter exiled in a strange land, an orphan who is not an orphan, a widow who is not a widow, Babylon destroyed and giant tanks lumbering through the garden, tanks in the garden where we began as Adam and Eve. Then Adam and Eve forced to pack their bags, exiled to a less fashionable suburb.

.

The woman from Iraq’s last email to me: Happy Birthday, I wish you the best wishes, I hope I’m the first one who remember your birthday, have a nice day and might be when I have time will do it again coz I will be busy tomorrow, have fun and wish you the best.

Her name translates as some kind of desert blossom. And like her fiancé, she vanishes as if never there, like an ancient civilization, like dew leaving a blossom as the sun rises. No answer on her phone, no reply to email, no answer to a knock at her door. Weeks went on and I finally received email from her, but it was spam, her email account hacked. I see her name, but it is not really her, she has been taken over, a regime change.

At a hockey arena in Canada I once heard a man say, “My truck’s got the same tranny as a tank in Eye-rack.” I never thought I’d meet someone who’d been crushed by an Abrams tank in Iraq. I hope the woman from Iraq finds a home, perhaps with her relatives in Chicago, a quiet home in the world.

.

Bush stands on an aircraft carrier in his flight jacket and Father Silas sits in his curtained hotel room where I drop by to return a book on art in Naples. Out of the blue Father Silas tells me that his favourite sister is a serious addict.

“She wakes up each morning and it’s a fight to not have a drink, not use something. I’ve seen it firsthand.”

So Father Silas detests levity about staggering drunks or stoners and he loathes people profiting from giant pub crawls. My eyes open: so this is why he is always angry at the group’s moronic drinking, so angry at Ray Ray’s APPRENTICE ALCOHOLIC pub crawl t-shirt, this is why he got in my face about the Italian American Irish pub.

“I worry some in the group will be on that same road because of Rome and I don’t want to encourage it. That boy from Madison, blotto every night, but he makes it for every class or trip, up wearing dark shades in the morning. He’s coping, which is a bad sign. I don’t want something like that to start on my watch.”

What about me, am I also coping on his watch?

If he told the group about his sister they might understand his anger, not dismiss him as a Puritan out to kill the party, to ruin Italy for them. Can one hold up a sign? My sweet baby sister is a heavy duty addict; please cut me a little slack.

.

“More vino?”

“Yes please.”

“I like to do a good thing now. Like today at the elevator, so they think about it and pass it on and it keeps going. It makes my day, it really makes my day.”

“A good feeling. I think I’m getting to that.”

“Mary, You’re almost there.”

“95%?”

“No.”

“91?”

“No, 80.”

“Only 80, only 80.”

“Sorry I’m so mean, I’m terrible, but Mary, I couldn’t lie to you.”

.

Go ahead and lie, I think on my terrace, please lie to Mary. For fuck’s sake, tell her she is 90%.

.

A lightning storm hangs over the mountains, an x-ray shudder, a heart attack of bleached light, then the world brought back to dark purple, back to now, a form of time travel, two worlds at once. Near our high terrace an invisible dog speaks in an urban cave and the barking echoes into every neighbourhood wall. Which window or room is the dog? The woman from Iraq was not used to dogs; in Iraq they are stray curs or guard dogs, associated with fangs or power, not a favoured pet in your bedroom.

Eve loves animals, bends to address every dog and cat she spies. This invisible dog speaks to something in the night and the two women on the next terrace speak their lines to the night as if in a play and I hear every word, yet my eyes never know their keen faces. Now I stop, now I close my terrace door on their secret mix of bonhomie and sadness.

.

We all believe we have a corner on sadness. In our Jetson future perhaps sorrow will be valued as a renewable resource. The immense power of sorrow will light our giant glass houses and pay the tab for our therapy and plastic surgery. In our jeremiad Jetson future they will mine our misery the way we frack the earth for shale gas pinned there like a cage wrestler. Our sorrow will fuel beautiful sports cars and sleek machines to Mars, our sorrow will employ our children’s nannies and reverse invasions and rescue the Euro and make shuddering markets rise in joy, our reliable sources of sorrow will make brokers rejoice and smile champagne smiles behind their complex buzzers and floodlit gates and blank limos.

.

An animal speaks, a piano echoes tidy counterpoint, and my small room sways above you in lightning, orbiting in a beautiful Roman sky, and the blind man walks our clean halls with his clicking white stick: Will you please ask them to be quiet!

He can’t stop the raucous partiers, those who drink themselves blind. I close my eyes and see Eve at the black sand beach in the bay under the volcano, her pale form stretched to the black sand – like looking at a negative. The blind man wanders eternally, I expect him to carry a lantern at noon, Diogenes searching the halls for an honest man, Diogenes searching the deck of an aircraft carrier lurking in the gloom offshore.

I walk down the stairwell with my eyes shut, I feel I owe the blind man that much, but on the stairs I fail, I have to look. Train your eye, he seems to suggest, see better, live better.

I will try. We try on mysterious shoes, have mysterious offspring. One child wants to be a priest, one wants to be a pirate. Like the snake-handler, and like me, Adam and Eve felt exempt from the fang. Something changed. We sin and are forgiven, we fly to and fro, we are on earth, then we are in the heavens, then we are not, we are on earth, then we are back in the silent cup of stars, then we are not.

In this world tiny things make me irritable and tiny things make me greatly happy. Like a stone in my shoe, like stars inside a chapel ceiling, or my high window in the night sky, its glass moon shape, and moonlight over arched doorways and ivory rooftops, moonlight making shapes seem profound and unearthly, but only for those who have a moment, this staggering light so secretive and brief and only for you and me.

—Mark Anthony Jarman

/

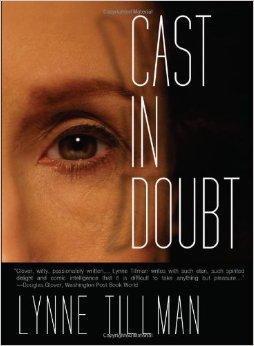

Mark Anthony Jarman is a short story writer without peer, heir to a skein of pyrotechnic rhetoric that comes from Joyce and Faulkner and fuels the writing, today, of people like Cormac McCarthy and the late Barry Hannah. He edits fiction for a venerable Canadian magazine called The Fiddlehead which, in the 1970s, published some of my first short stories (and another story is coming out in the summer, 2011, issue). Jarman has written a book of poetry, Killing the Swan, a hockey novel, Salvage King Ya!, four story collections, Dancing Nightly in the Tavern, New Orleans is Sinking, 19 Knives, and My White Planet, and nonfiction book about Ireland called Ireland’s Eye. “Exempt from Fang” will appear in Jarman’s forthcoming short story collection Knife Party at the Hotel Europa (Goose Lane Editions, 2015).

Fides Krucker in Julie Trimingham’s Opening Night

Fides Krucker in Julie Trimingham’s Opening Night

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto. Her film work has screened at festivals and been broadcast internationally, and has won or been nominated for a number of awards. Julie taught screenwriting at the Vancouver Film School for several years; she has since focused exclusively on writing fiction. Her online journal, Notes from Elsewhere, features reportage from places real and imagined. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was published in 2013.

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto. Her film work has screened at festivals and been broadcast internationally, and has won or been nominated for a number of awards. Julie taught screenwriting at the Vancouver Film School for several years; she has since focused exclusively on writing fiction. Her online journal, Notes from Elsewhere, features reportage from places real and imagined. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was published in 2013.

18 (2012)

18 (2012) blow up, the yellow house (2014)

blow up, the yellow house (2014) Levitation (2014)

Levitation (2014) Wolves Evolve (2014)

Wolves Evolve (2014) Apocalypse Now (2012)

Apocalypse Now (2012) Ghost Brides (2012)

Ghost Brides (2012) Merry Christmas (2013)

Merry Christmas (2013) On Sale! (2012)

On Sale! (2012) Willingly (2014)

Willingly (2014) Red Carpet (2012)

Red Carpet (2012)

Lise Gaston. Photo by Josh Davidson.

Lise Gaston. Photo by Josh Davidson.

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Samuel Bowles

Samuel Bowles

Shambhavi Roy

Shambhavi Roy

Translator David Need

Translator David Need

Photo by Fred Filkorn

Photo by Fred Filkorn

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau Karin Fossum

Karin Fossum Jo Nesbø

Jo Nesbø

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Lisa Moore

Lisa Moore

Figure 1. Steven Smulka. “Solar System.” 2011, Oil on Linen, 76.2 x 116.8 cm.

Figure 1. Steven Smulka. “Solar System.” 2011, Oil on Linen, 76.2 x 116.8 cm. Figure 2. Ralph Goings. “Double Ketchup.” 2006, Pigmented Inkjet on rag paper. 22×32.75 in. Edition of 30.

Figure 2. Ralph Goings. “Double Ketchup.” 2006, Pigmented Inkjet on rag paper. 22×32.75 in. Edition of 30. Figure 3. Randy Dudley. “Coney Island Creek at Corpse Ave.” 1988, Oil on Canvas. 28 1/2 x 54 in.

Figure 3. Randy Dudley. “Coney Island Creek at Corpse Ave.” 1988, Oil on Canvas. 28 1/2 x 54 in. Figure 4. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Vaatwasser” (“Dishwasher”). 1998, oil on canvas, 185 x125 cm.

Figure 4. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Vaatwasser” (“Dishwasher”). 1998, oil on canvas, 185 x125 cm. Figure 5. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Girl with a Pearl Earring in Plastic”. 2002, oil on canvas, 75 x 60 cm.

Figure 5. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Girl with a Pearl Earring in Plastic”. 2002, oil on canvas, 75 x 60 cm. Figure 6. Cynthia Poole. “Displaced Mints II.”2011. Acrylic on canvas. 100 x 120 cm.

Figure 6. Cynthia Poole. “Displaced Mints II.”2011. Acrylic on canvas. 100 x 120 cm. Figure 7. Tom Martin. “One of Five.” 2009, Acrylic on panel, 90 x 90 cm.

Figure 7. Tom Martin. “One of Five.” 2009, Acrylic on panel, 90 x 90 cm.

Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

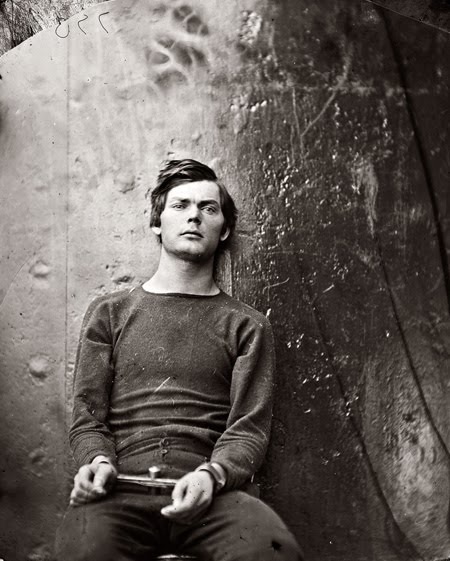

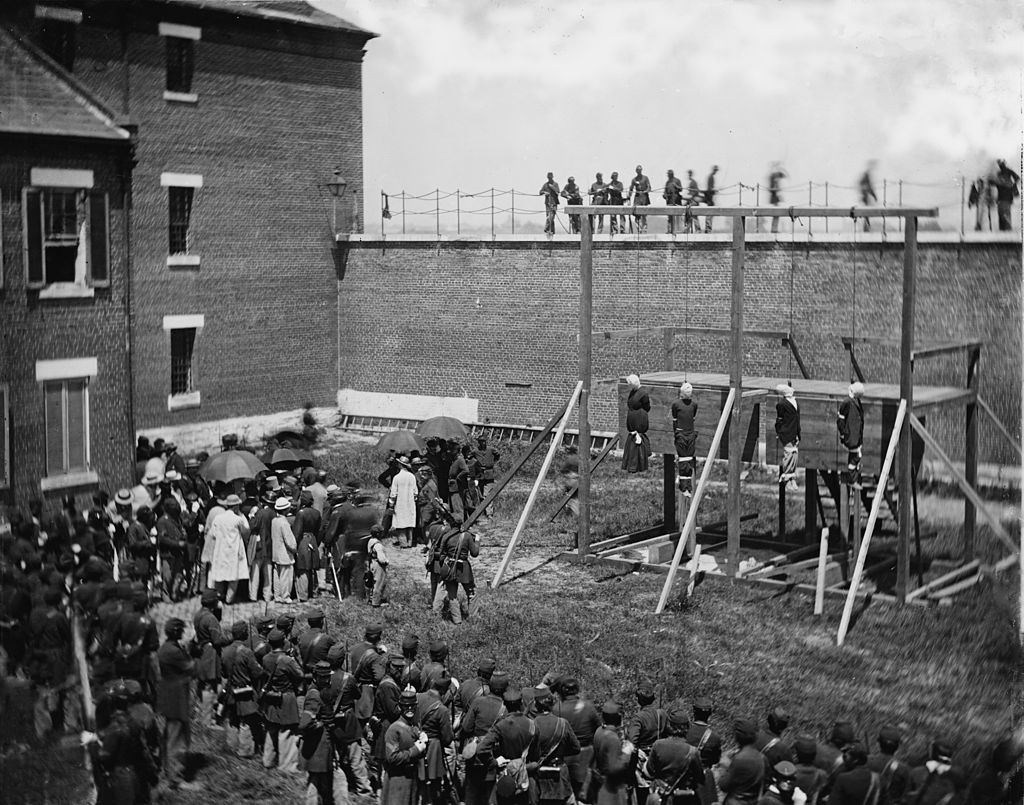

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Richard Farrell

Richard Farrell