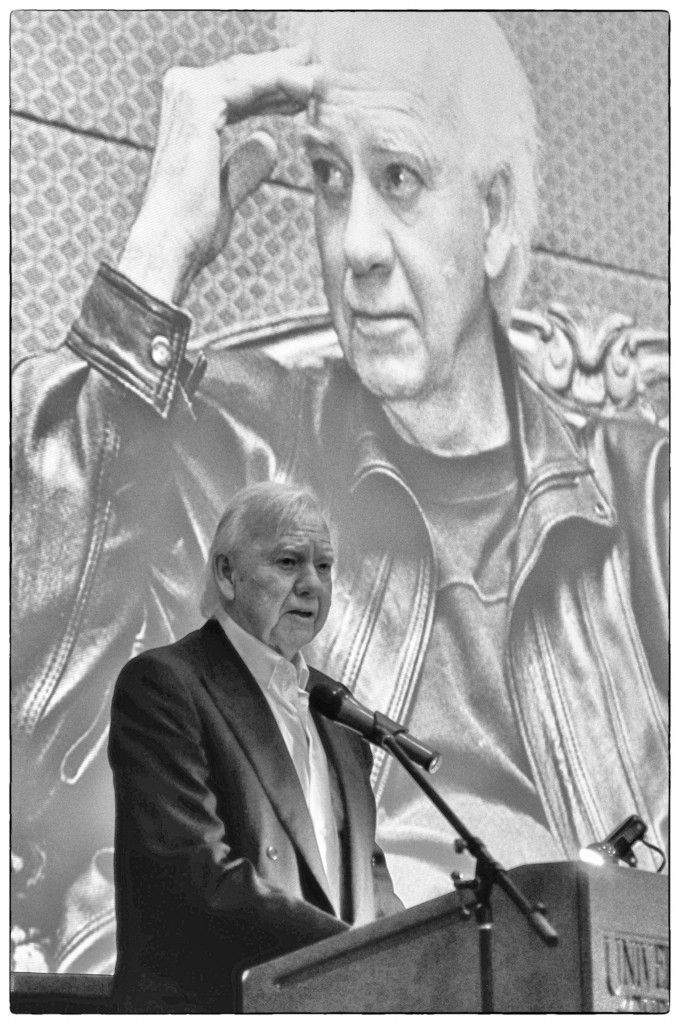

Leon Rooke. Photo by Tom King.

Leon Rooke. Photo by Tom King.

It’s a huge honour and pleasure to introduce to Numéro Cinq my old friend Leon Rooke who, all my writing life, has been an inspiration and a forerunner. This amazing story–“Son of Light”–appeared in Leon’s 2009 collection The Last Shot for which I wrote a review that ran in the Toronto Globe and Mail. There is possibly no better way of prefacing this story than to give you the review, the whole thing.

Leon Rooke is a Canadian from North Carolina with a list of books as long as your arm. He’s a national treasure, a huge and kindly promoter of younger writers, a Shakespearean reader of his own work–have I mentioned prolific? He writes out of a wagon load of traditions which include the American post-modernism of Barthelme, Coover, Gass and Brautigan and the school of southern bombast (William Faulker, Barry Hannah and Flannery O’Connor–and by “bombast” I don’t mean a negative; I mean the high-flown stentorian style of the great southern preachers, rhythmic, hammering, mellifluous and grand).

Rooke eschews the dreary wet wool blanket of conventional realism, salting his stories with magic, myth, vituperation and improbability. Often, out of the most dark and moribund situations, he wrestles a startling and uncanny beauty, an affirmation of life, a stunning reversal that does not bespeak any faith or philosophy but a joy in the exuberant play of language. Like his contemporary Alice Munro, he writes outside the box, he writes to push idea of story to the limits and beyond. You sometimes read a Rooke story just for the exhilaration of seeing whether or not he can carry off the high-wire experiment he has launched.

In his new book The Last Shot, you will find stories in the southern style (in the Appalachian demotic of his novel A Good Baby), also parables, myths, burlesques, tirades and tender, wistful love stories. The famously reclusive J. D. Salinger appears in one story, haunting the garbage dump where his refuse ends up to make sure no one steals it. In another story, a magical (or literary) plague of moths invades a Mexican village and delivers a kind of aesthetic grace; it ends “…I felt for the first time what a glory it was to be alive in such a dazzling, incomparably fantastic world.” In “Magi Dogs” a painter paints a dog into a picture of a house and the dog comes alive. In “Lamplight Bridegroom 360″ a mysterious angel robs a bank, mystifies a crowd of witnesses, and delivers the money to a woman dying in a hospital so she can pay for treatment. Somehow the bank staff doesn’t even know it’s been robbed. In “How To Write A Successful Short Story”, Rooke hilariously sends up creative writing how-to books and conventional ideas of story (all those the ideas and theories he actually avoids) and incidentally tells a story.

Lately, Rooke seems to be interested in the technique of intercalated stories: I don’t recall seeing him do this before in quite the same way. Stories interrupt and delay other stories. The darkly comic novella “Gator Wrestling” is a novella mostly because of the this structure–the heroine Prissy Thibidault just wants to get across town and see the gator Rufus Seed Junior has caught but Rooke interrupts her journey and her story to tell the stories of just about everyone in town before he allows her to get to Junior’s house and see a mob prodding the somnolent gator with paddles till it ups and rips off Acy Ducey’s arm. Then, in Rooke’s version of Aristotelean peripeteia, magic unfolds: Rufus Seed Junior and his entire family, who have always wanted to go to Africa, turn “a lovely light chocolate”. We refrain here from drawing allegorical conclusions–Rooke is not writing a politically correct racial parable; mostly he seems to be having fun playing with stereotypes and attitudes.

I deeply admire the story “The Yellow House” (I included it in Best Canadian Stories when I was the editor) which sets up camp in a dreamy, fairy tale universe (part-allegory, part Italo Calvino of, say, Cosmicomics): there are two houses across the road from each other; in one, every one is sickly, melancholy, hopeless and dying, with an expansive cemetery attached and one “untidy” peach tree (sort of an inverted Garden of Eden); in the other, everything is bright, cheerful, loving and yellow. One day, for no reason except love, a boy from the yellow house walks down through the cemetery to pick the peaches, then he approaches the sickly house and proposes to the last remaining sister Precilla and kisses her fingers.

Suddenly, in a burst of Rookean afflatus, things get better, the sick house is flooded with yellow light, health blooms, sex is about to happen. “Out at sea, storm clouds were forming, tumbling and turning. A tumult of wind swept low over the water. Over the roof of the yellow house could be seen schools of silver fish in flight inches above the water. School upon school of these silver fish, all flying.”

It makes no sense to ask precisely what this means–something about the mystery of love and the delight of story-telling: in stories, grace can strike like a bolt of lightning and fish can fly over houses.

But maybe the best thing in this book is “Son of Light”, a gorgeously written pseudo myth about creation and death (whose name, in the story, is Dark). “I am death, Dark thinks. I could change you utterly.” The passages in which Dark haunts a mysterious desert oasis, sleeping unseen amongst the nomads for company, are an extraordinary blend of the Biblical, inarticulate dread and amazing intimacy. Only Rooke could write death (Dark) as a lonely young man stuck in a desert, curious and affectionate towards humans who are only partly aware of his presence, awestruck, mistrustful, yet somehow able to live with him.

There is something here, some magic Leon Rooke does with a twist of his hand, a complex image of the relationship between life and death, strangely humanized and desperate, comic, sweet, uncanny and so achingly beautiful you wish it were real.

dg

/

BABY DARK

His presence on earth was not a known thing: Dark, the baby. But out here on the long plain, the flat horizon around him like one thinly-sliced peel of orange, he lived well enough. Well enough, that is, to keep living. Dark could sniff where there was water. He could sneeze, and there was water. Where water was he dropped anchor. Anchor and seed, seed from a full pocket. Animals came, first one, then many. Birds dropped down. Grasses grew. Strange fruits. And, from to time, in the beginning to his distress, people.

All these desert oases–not that many–were his. His work, we should say. Proprietorship as such did not interest him; the occasional nomads appeared; they appeared first on the long straight, trudging single file, cresting one solitary dune after another. Onwards to the oasis. Where the first dropped down, over time dropped down the many: their parched black bodies falling in a heap. Skin hard as leather. What did they do with themselves before this oasis existed? Well they would not have come this way would they? An oasis exists, one heads for it. How otherwise may this long plain be traversed? Let us not be silly.

They crouched in Dark’s water, studying the depths as though for monsters. What is that? A water lily. What does it do? It flowers. And then you eat it? They sat so for hours. They sat on rocks, in his palm trees, on the groomed sand he each morning raked with his fingers. They watched each other and the horizon. If a storm was to blow in, if a cold front threatened, they shouted the announcement, arms flailing. In what seemed initially to Dark’s mind to be gibberish. Some time passed before his ears–unaccustomed to any sound except wind, storms, heat so charged it had its own many tongues–consented to think twice about the jumble issuing from their mouths. They spoke a kind of bejangled song, often dirge-like–until one learned to make in one’s own ears specific tonal adjustments. Then–amazing–it was music.

Against the night’s cold they wore skins, frayed furry jackets, lamb it was. Or kangaroo, wallaby–the hides of tree monkeys to the south. Kangaroo were plentiful out here, together with foxes, wild dogs, sand rats, but where had they acquired lamb? Otherwise they went about largely naked. A wrapping of skin which flapped over the groin, occasionally over the buttocks. Over the head. Looping down the neck’s backside. Bones looping the ankle, the neck. White-ringed eyes to lessen the sun’s glare. Their bodies for the most part were tall and leanish, some might say emaciated. One was aware of bones–a frailty?–in a way that one normally isn’t. Tall? Well, he rid himself of that view soon enough: once he had placed himself beside them.

Who’s there? they would say. In that high-pitched squall their voices clung to when frightened or angry. Or were they merely inquiring, as a fox might? They looked tall only because such meagre flesh adhered to their bones.

Dark rushed to no judgement on this. He was scarcely more than skeleton himself.

Large flat feet with over-large toes, toes all but horned: eyes that were ever in drift towards the horizon. They marvelled at certain cloud formations: caravans of bodies not that much different from themselves. Their children, Dark noticed, even-those new-born, had coarsened skin. A child fresh from the womb was immediately pounced upon. The soles of the feat were beaten, the pinkish hands dipped in briny liquid. Brow and scalp roughened.

Dark held these infants sometimes in his arms, if their mothers were otherwise occupied. How strange! He had never before beheld an object so incredible buoyant. He probed inside these babies’ mouths. Into every orifice. Surely these bundles were not of this earth. It was like holding…nothing. Until it moved. Until it squiggled. Until it wrestled itself over, clutching for something. Well he knew what it clutched after. He had witnessed the deed often. The creatures attempted nursing at whatever object picked them up. Always hungry: how interesting. Propped against rock or tree, they would attempt to nurse that. It was funny. Dark liked it. True, a pup in the wild would do the same. Still, the instinct engaged him.

He could watch these newly-born–mesmerized–these elongated black lumps–for hours.

They seemed never to cry. He remembered with chagrin his own crybaby years. His own fondness for the teat. Crossing impossible hills–wind, rain–an endless freeze. The Death family, eternal voyagers. Nomads themselves. Endless freeze, yet a warmth that also seemed to go on forever. Take it, sugar. Take the sugar. It was not that long ago. Ages, but what were years to his kind’s reckoning?

A single season that time of his youth was: so it seemed to Dark now.

These bonesome nomads had a hardiness he lacked. A backbone he never had acquired. Yet they followed the sun–they tramped onwards–much as his own parents must have done.

Here they came. First one dark shape on a far dune. Hanging there. Gesticulating. Arms flaying like a beetle upended. Quaint, Dark thought. What transpires there? Then another cresting a more distant rise. The same flaying arms. Hither, come hither. My nose smells water. Onward, one dune after another, those solitary marchers–until, unbelievable, here were the many. All falling in a heap where the first had tumbled down.

Finished, you would think. By thirst, famine, disease–by whatever. Then the one eventually crawling on hands and knees from the heap, scuttling on all fours until some benign impulse arrested his progress. Slowly rising. Other heads lifting. Then a full crawl of black bodies. Finally, all in assembly, upright, gibbering and jabbering.

Often the nomads would unfold their cloth, their poles, tent themselves from the throbbing heat. Unfold their goods. Amazing, the multitude of goods. How were these objects transported, when they travelled so denuded?

A mystery.

Well was he not himself a mystery?

More and more the mystery. Over years–how many?–it came to Dark that he was interested. These nomads, they beguiled him. How could such bones–blackened as cooked rabbit, bony as plucked bird…how could they prevail? How was it they had come to imagine they could?

Sometimes they remained a night, remained several nights. Never more than a week, two weeks. A month–six?–at the most. Where were they going? What strange purpose drove them forward. To what purpose, what end? What was out there? Or there was this: often he would see them out on the dunes, first the one, then the next. He would drop more seeds, find more water. Prepare for their arrival. But where had they got to? He would himself advance over the sand to meet them–not easy!–and espy them miles and miles in the distance. Crossing the long straight, cresting a dune–advancing his way, yes!–but at a certain point, at one specific dune on the long plain, each arriving party veered. Turned away. Why? There they went, heading off elsewhere. He knew these dunes, knew better than any. A thousand times he had traversed them. Nothing was out there. No oases beyond his own. A thousand miles of desert, desert almost without end. Where were they going? Month upon month, and where were you? In a place no different from that place in which you had found yourselves the day before. Nothing to eat, no water to drink, nothing to see except the same stretch of sand, the same sky, the same nothingness. Desert waves, boiling sun. Kangaroo, foxes, dogs, yes–but fewer by the year. And no water. No vegetation other than the rare scrub bush. A tuft of…had this once been grass? Bones. A bird carcass now and then. Flinging itself along through bands of pulsing heat until, exhausted, the wings of a sudden fall still. Down comes bird.

Yet there these nomads went. The space was theirs, he supposed. Always had been. It must be occupied, surveyed anew, found and found again. Might an intruder such as himself otherwise establish domain? No, they cared not a whit about him. His like had always been present. His like explained the barrenness, the lifelessness, the hard grabbling for whatever stock came to hand: the odd growth of thistle here, the patch of grass there. A running hare, a bird, a fox, a snake, a frog, a turtle, a dog. Gristle uprooted from the sand. What more was required? What more had ever been theirs?

But they did come. A relief. Dark had come to desire, even prefer , their company. Often he remained with them in their tents–frayed cloth held aloft by thin sticks–intrigued: they spoke little, laughed rarely. At the antics of small children playing. There’s a beetle crawling over the sand. Let’s pour sand over this poor crawling beetle. When the beetle at last emerges–befuddled, lost, disoriented–they laugh. Let us heap more sand on the beetle, that we may laugh again. An entire day a child might do this–intent as scholars, the beetle’s fortitude against the abysmal heavens as relentless as their own.

Searching for lice in one another’s hair, grooming that hair, was likewise a serious business. Many bones, twigs, the odd stone, rolls of dead leaves, twists of rusting wire, were to be seen in these heads of hair. Each item carefully laid aside until the cleansing was done. Then washed with spittle and, as carefully, restored.

Any evidence of color was disavowed. Vermilion, any color with a reddish hue, most particularly. At his oasis, any leaf so saturated was discussed endlessly. Then buried. Buried deep. A man or woman, never a child, might spend an entire day digging, digging. Remove this leaf that it may never again be seen. Let the hot sands deal with this. Should it possess an afterlife, let it not be ours.

So, too, a child whose nose dripped the color. Bury him in hot sand until the color ceases. Then whip him so that hereafter

he may not make us endure the ordeal.

The dead were unhappy. It was their blood coloring the leaf.

It amazed him: all those laws laid down. From where? Excuse me, but what is your source?

They smiled, discussed the issue, when a wild dog howled in the distance. Who goes there? By twilight, already they were asleep. Side by side, often in piles, limbs entwined, with no sorting arrangement he could decipher. You slept where your body fell.

They ate little. In fact, next to nothing. A fire, in the general scheme of things, was not required. Fire, on a whippingly cold night, offered its rewards, generally without respect to supper. What would they cook? Could air be cooked and eaten? Perhaps. In fact, very likely. In fact, what else could so winsomely convey the fragrance? Was this not how he had been feeding?

But these nomads had not the knack. They carried sharpened sticks, tools for hunting. Lures, traps. But out here? Certainly there were desert foxes, moles, kangaroo–but how often in this wasteland did one see them? Spiders, aphids, mites. By day, sun baked the land relentlessly. By night, whistling wind, a near freeze. You could be sure that if a thing moved it was not a thing alive. Not a thing that could be eaten.

Dark they saw and did not see: it was that kind of business. He would be drowsing, the heat invited such, would open his eyes, and one or more gaze would be upon him. An elder, sometimes a child, often women, poked with a stick that space which he filled. No matter. Sticks could not harm him; their thrusting was a nuisance, no more. They made no attempt to rid themselves of him entirely. His presence was an oldish thing: it was dangerous, the sticks, the gazes, but they could not refrain from expressing their discontent.

Perhaps they understood the water, the grasses, the fruits–this oasis–was his creation and they sojourned within it by his pleasure. It could be. Or it could be that this had not occurred to them. Perhaps they believed the oasis had cast itself onto the sands in the same manner that they had been. He was an entity apart from them. A being in whom blood did not course as it did within themselves, but a being nevertheless. May it keep its distance, may it not sojourn into our flesh, may it do its hunting elsewhere: that is all they asked.

Many of these people Dark now knew from memory. He knew their names. Since his own infancy, in a manner of speaking, they had been arriving; now many were old. So he felt himself to be: old, abandoned, all but useless. He did not regard these interlopers–that they certainly were–as his friends, not exactly. Yet he admitted to queer satisfaction: he liked them. Liked their newborn, their aged, their in-between. He was entranced that their personalities adhered to such meagre variance over the years. A new tribe arrives, how much it is like the previous one? Yet in this regard they could surprise him. They could indeed. Uncanny, their presences in regard to this. Such a multitude of paths they struck, yet how frequently the paths circled back. A youth, now grown old, how the mantle of youth still clung to him. Look at that old man sitting in the sand playing with his beetle. Amazing. Well was he exempt?

Notwithstanding this: many, mean and unkind, pure devils in childhood, were gentle and caring later on. What explanation here?

He remembers from his own youth a storm at sea: lightning bolts by the hundreds, each striking simultaneously: like a tree upended, lightning along every limb, igniting from every bough, the sky lit from horizon to horizon. Days on end, no relief. Thunder so fierce its origin seemed to be within you, of and from those scuttling about the heaving deck. Fires everywhere, bodies picked up and flung into the sea. Six times he had himself been struck by lightning, all within the space of seconds. Lightning skating on water, the sea boiling.

All hands lost. The ship shattered into a thousand pieces.

His work? How could that be, when he was himself floating? Fish of a silvery hue drifted around him in untold number: schools of death; among them, lumbering black sharks split apart far within the depths.

*

Dark has endured similar storms here. Lightning without cessation, wind and rain without end. Wind strips away your being, rain soaks inside, lodges in the heart. Parts of himself are out in the desert, being nibbled at by sand rats, insects: excuse me, what’s this? Edible? No.

During these storms he now huddles within himself, shivering, locked in his own tight embrace, still as snakes coiled on cold chimney hearths. Lower than snakes, elsewise why his exile here?

His mother soothes him, opens her blouse. Fits a swollen nipple to his lips.

Eat. Sleep. Think nothing. Mother is here.

He wants to go home. Where is home?

A while ago at his oasis an old woman, arriving sick, so misaligned in her features that her sickness might have been diagnosed as leprosy, had died during the tribe’s stay.

Their eyes devoured him. You! they said. Ugly one!

He was innocent. He was not even certain he would remember how. He had in fact, out of curiosity, the intrigue of elements now beyond him, held the old woman’s hands as she slipped away. She had looked into his eyes, at first fearful, then nodding. Yes. Yes, she said. You are innocent. I absolve thee. Such a relief that was to him; his eyes moistened, he would have called her back had he the means. He was not her nemesis. Her nemesis was within.

Clean her body with sand. Elevate the face to the southerly direction. Oil the soles of the feet. Fold a bone within each hand. Seven times encircle her body. Each time snip away a cutting of hair, a cutting of nail, a snippet of cloth. Wedge of skin cut from the thighs, should the dead be unmarried; from the belly, if she is.

In the desert, a dog slunk near him, no more than its own space away; it whined miserably, regarding him through scarred eyes. In the distance other dogs watched. The dog inched forward, lay its head in his lap. Foam leaked for the ears and mouth. With a jerk of the head, the dog died.

I’m innocent, he thought. Death arriving as light from the primeval void, light’s speed versus known and unknown obstruction.

I must quit this place, he thought .

The tribe ventured north. He trekked along for the company. They came to rocky shelter whose inhabitants greeted them as though with little comprehension. They ate. Music of a peculiarly Old World kind was played–a somewhat barren sound, reedy, as though it had long been confined to earth.

He loved the cold caves they slept in. A very beautiful young girl slept beside him an entire night: his eyes open, watching the dark. Listening to her heartbeat. She knew someone was beside her–initially she was on guard, without being precisely frightened. Once during the night, she raised up, lifted her thin arms, yawned, then collapsed back into sleep.

He must himself have slept a long time–years perhaps. He waked to a feeling of emptiness, cold and trembling, unable to think where he was. The word ‘tomb’ came to him. Then, ‘entombed.’ That brought a laugh, and he felt better.

He was hungry, starving in fact, but whenever was that not the case? Insects were crawling over him. They must have believed him dead; if, that is, insects held beliefs–which thought brought on another smile. It was at this point that he realized he was enjoying himself. He held aloft one of those insects: a hard dull shell the color of the stony world it inhabited: all those wheeling legs, the waggling head, the bulging eyes–yes?– and found himself entertaining a ludicrous, if wondrous thought. What if he could mate as insects might?

In the cave the nomads had been digging a well. The digging had been going on for thousands of years. Workers were lowered by rope into darkness. If you listened carefully you could just hear the resounding hammer and chisel. No more than two could work at a time, and the best workers had to be down longest. No one wanted to be thought of as a best worker and for this reason they were habitually complaining about how worthless they were when it came to hammer and chisel. Workers who remained too long were blind for days and days. They emerged, walking in circles, babbling. Tumbling over. Blindfolds were affixed to their eyes. They had to be led by hand to food and water. They seemed to know no one. They believed a black cloud hovered about their heads; they succumbed to panic and flayed at the blackness. They had to be restrained, locked up, put into a cage, or they might do harm to themselves. They spoke of coming across strange parties down there–parties whose outside was inside, who flaked into nothingness when touched, a nothingness that then took shape inside themselves. They screamed through the night. Occasionally they did not emerge from this madness, and were ever venturing out upon the sun-drenched dunes. Disappearing.

No one could accurately assess the depth of the great well. Each measurement had a radically different result. A thousand years digging. Why?

The hours of the day admire their every tick. Each second is a thrill.

The day’s heat was tight knobs of air. You would see out over the desert a massive army trudging your way. But it was heat walking. Heat walked under your shade and the shade burst into flames. Flames out on the dunes, where the very air had caught fire. The very sands did. One’s very eyelids did. Red ants strode the horizon. Fire plants bloomed in the sky: a red forest. Clouds aflame.

He caught a cold, caught worse, and for months curled up into a corner, whining softly, in embrace of himself. Bats hung by day around him, at dusk, first one, then a second, then all in harmony stirring their wings–gone.

A letter was found. Who knows how long it had been buried in the sand? The paper disintegrated in his hand. This hardly mattered. Deciphering ancient texts was old stuff to him. Where he was defeated was in capturing the tone.

Come home, the letter said.

THE HOSPITALLER

In the city, at Dark’s favored hotel, the hospitaller rushes from his office to greet him. He bows effusively, smiles with the excesses of one in rapture. The hospitaller invites him inside his tiny office. Offers coffee, tea, a biscuit. A glass of plonk, my esteemed friend, or is it too early? Something stronger? This man, like Dark himself, is not native to these parts. He is a newcomer, like the Sikhs, the Germans, the Chinese with their restaurants, the Asians with their taxies. A hospitaller, he knows the importance of a grand welcome. Kiss the lady’s hand, marvel at the arrival of the hatless gentlemen from the desert. Let the man know that his heart beats only for such arrivals: in your absence I have been as a man sick with fever, afloat in apathy, aswim in self-pity. Incomplete. Now, my friend, you are here, and the sun has returned to its proper orbit. Here, let me take your coat. Loosen your tie, rest your feet on this stool.

Travelling so takes it out of one, I’m an innkeeper, do I not know? It tires one, it bags the bones–but, ah, the exhilaration, those new worlds, each of which must be conquered.

All the same, alas, dear friend, we have no vacancy, none at all. How wearisome, I am abject, my apologies! If only I had known you were coming, if only–dare I offer this criticism–if only you had called in your reservation.

The usual, then?

Why, yes, of course the usual. What you must think of me! That I, a newcomer like yourself, in exile, so to speak, like yourself, would turn away a traveller of your distinction! The traveller must be rewarded, must he not? Where would our universe be without the traveller? Marco, Marco Polo, did he not set the pace? Is he not our model, are we not in his shadow? Even you, signor, a foremost globe-trotter. Another glass, then, for our unparalleled Marco–cheers, skol, salud, salute, bottoms up! If we did not have business to summon us, I would say let’s empty the decanter.

The hospitaller’s sofa, then, as usual?

Of course, my sofa. The honor is mine. In there, the little toilette where you may shower and shave, the small shelf where you may stow your belongings. The same peg to hold your coat–oh my, oh my, is it ever dusty. Oh, you travellers, the endurance, the struggle, wind, snow, and rain, but the road is ever there, is it not, it ever beckons. Marco Polo, what travails were sent his way. But ever onwards, onwards, is that not the theory. Onwards, for what awaits us around the next curve, dear me, those spices, can we help being chilled with wonder! But forgive me this prattling, I see you are exhausted. Such long days, such long nights, and nothing but bedbugs, bad water, dust in the nostrils. Tomorrow, by all means tomorrow you must tell me of your sojourn in the desert. The desert, it changes one’s perspective, no? But later, yes later. For now, stretch out on my long sofa, pure leather, black as miner’s black lung, beautiful, is it not? Here, let me slip off your shoes, I shall have them polished. You need tending, sire, no question, you are looking bony, ragged, lustreless, if I may use that word. Near death, if I may speak frankly. But a wee catnap and you shall be yourself again. I’ll lower the lights, if I may, let me spread over you this soft coverlet. There you are, yes, close your eyes. That scalp will need looking after, you know, it’s baked, your poor noggin is a sea of blisters. You really must wear a hat, you know. Our friend Marco without his hat, what would he have accomplished? Signor, why did you not follow his example?

Ah, my voice tires you, my apologies, my pleasure in seeing you yanks my tongue one way and another. So sleep, my friend, rest the weary bones. Then onwards, onwards, side by side with dear Marco, eh? I understand, a man of your calling may not tarry, may not dally. My heart will ache, I shall brim with sorrow at your absence. But you will return, will you not? Of course, you are the hospitaller’s glory, without you what purpose would I serve? Until the next time, then, signor! A private room shall we waiting, I promise you, I shall keep the reservation open. Yes, always open, what, in this day and age, that a being of your distinction should be compelled to inhabit a stable?

What? Excuse me, signor, did I hear you correctly? You wish to go home? I am distressed, signor, I will weep tears, but it is as you say: even our friend Marco must from time to time return home. For restoration, to shore up one’s vitality, to see the family, to net our grievances–one or the other. It will be our loss, signor. As you say, your heart has too long been riding the bumpy wagon. Are those tears in your eyes? No worry, we all have them. Shall I say it, signor? Your work here has not gone unnoticed. Your presence has been remarked upon, and not, alas, always agreeably. People talk, you know. Callous remarks are passed. But take no notice, signor: beings such as ourselves, are we ever applauded in our own backyards? And yet, signor: a single drop of moisture on the dry tongue, is that not sweetness of a kind to keep us steadfast, even fertile, in our labor? The beetle on the green leaf, is he too not in part the dreamer? The cloud passes overhead, does not the worthy traveller say Hello, as to a fellow sojourner? So, go home, yes, signor: by all means make the journey. Was this not the motivation for dear Marco’s incredible journey? That his mother should kiss him?

Be assured, signor: the hospitaller shall make all arrangements. Putt-putt, yes, a ship, this is your one available choice. Unless you have learned to walk upon water. No? Then sleep the sleep of an innocent child, old friend. Leave all picky details to me, your hospitaller.

*

Dark, in his sleep, already walks the ship’s deck–the sea easy, a bright moon hanging. To see the world through the eyes of his blind hospitaller, he thinks: how strange that must be. I steer myself by the sound of another’s breathing, the hospitaller had said to him at their first meeting. On a city street this was, in the long, long ago–Dark lost, after an endless time drifting–the hospitaller’s hand a sudden gentle touch at his elbow. By my lights, this is among the heart’s major duties. But you do not breathe, signor, so it was with difficulty that a blind hospitaller could find you. And now that I have, as I am sightless, it must be you who guides me across this noisy street. Take my arm, signor.

Your arm? What was I previously touching, hospitaller?

My heart, signor. Mind the curb now.

*

Let us stroll along together for a while, signor. Like our friend, Marco, arm-in-arm with a spice merchant, negotiating terms, let’s say.

How did you come to be blind, hospitaller?

Who knows, signor? Every hospitaller is, that is how matters stand. Long ago,

a nail driven

through a board

split that board

A blind man

passing by

was first to notice

so it came to pass that every hospitaller, as a condition for employment, must be blind. Marco Polo, recall, told his crew his ship’s flag must flutter against wind. Otherwise the world’s true spice capitals would elude them.

I do breathe, hospitaller. Your exhalations are my inhalations. As your breath crests a wave, mine is the stilled water in wait between.

No, signor. This not breath.

SHIP AHOY

What a surprising cargo: in the ship’s hold are bags and bags of pomegranates.

Mice and their ferocious kin nose among the bags, nip the ripening fruit. For nourishment, they prefer the burlap. Dark secures a space for himself among the lumpy bags, here his head, there his feet. The vermin sniff his calloused soles, probe the thick curvature of his nails. They lift their gleaming, scornful eyes: why are you here? What business do you have with us? We want cheese, peanut butter, bacon, New Zealand beef. We want to lick grease, sing songs, dance. Pay attention. Open your eyes. Talk to us. Explain yourself.

Or it may be that they mistake him for one of their own. It is not as though they are given to civility even with each other. Only when cornered by a seaman with a broom is their affinity with common humanity displayed.

Water sloshes along the boards, wetting him. Back and forth, slosh, slosh.

No matter.

Scum, algae, wasp dens, dirtdauber lairs, seaweed, moss, barnacled growths–up there, light spilling between boards, a tropical fern– occupy the walls. A trapped bird flutters endlessly about–in misery, in consternation, scummy-eyed, the head bloody, feathers sparse.

No matter.

Dark rises sorrowfully: his bones ache, movement is a torture. The bird obligingly flies into his cupped hand. He strokes the bird until its tremors cease. Such a quick, urgent heart. It could be the hospitaller is right: he has no heart to beat such as this. A rat glares at him. No favoritism, the rat says.

Daylight. Blinding daylight, he must rub his eyes.

The bird crouches in his open hand. The small heart palpitates, wind ruffles its mite-ridden feathers. I don’t know why any of this has happened to me. Were I a thinking bird I would take up my situation with a higher authority.

Even up here away from the hole, in cutting wind, one can smell the lush aroma of pomegranates.

The bird lists away; it steers a faltering course before wind halts its progress altogether. It hangs motionless there, fighting the wind. Why will the creature not turn, let the current sweep it away? Matters are not as they should be. Must every breath be an ordeal? The bird’s wings close, wind releases its grip, the bird plummets. This it recognizes, this it knows. It has been here before: this is mere acrobatics, a question of instinct, something in the bones. Time to soar. But all at once the bird is swooping past him. It flits back into the familiar black hole.

Dark’s feet feel entangled as though by ropes.

Now rain. Hard rain. So much rain.

He remembers seeing once, in the desert, in rippling heat thick as lava pouring along a shelf, a fleet of tall ships skimming the sand. Then the ships one by one burst into flames.

One time, a scrap of paper flew up into his face. Worn by wind and time, tissue-thin, bleached by sun. Indecipherable.

The nomads encamped at his oasis were absorbed with his table, the table where sometimes sat to think deep thoughts. They sat on his table, eating their food. Each had to crawl beneath it to study the table’s underside. They turned over the table and laughed at the four legs thrusting into air. Like woman, someone said. They shook the legs, laughing. They counted the legs. Like two womans, someone said. They laughed harder. An elder dropped down, mounting the table. Not like two womans, he said. No one laughed. They looked with unforgiving silence at the table. After a few days they scorned it and him. The table to them became invisible.

In the ship’s forward hatch a seaman obsessed with walls is placing love inside a very small box. Carefully, as though he holds a precious vase. Now he is wrapping the box in material so much the color of his own flesh he seems to be without hands. He will pitch his little box over the side when no one is looking. That is how certain kinds of love are dispersed into the world, he tells Dark: an open sea, no one looking.

Out on the sea the waves lash out. Foam spews from every mouth. The waves curse the wind, which curses them. Each wave curses the day it was born. The wind loves what it is doing.

Just look, wind says, at those hideous waves. The waves will have nothing to do with each other until they strike shore, where they will attempt to chew every predecessor into tiny bits.

Look at that stupid box. Where does it think it is going?

Look, there’s Dark looking at us. He looks as beaten about as we are: he can hardly hold up his head.

He dreams. It amazes him, these other worlds that slumber inside him. The rabid dog crawling up to settle its head on his lap. Uninvited. Stroke me, the dog said.

In a forward cabin, the skipper too is resting his head, closing his eyes. Thinking, If only I knew where I was going. If only.

The Captain is plunged into solitude. That is why he is drinking. Something like this always hits him midway a journey. He is lulled into grief precisely at that point in a journey when a thousand ports are scant hours apart in terms of the time necessary to reach any one of them. The Captain is certain his cargo–pomegranates, how strange!–would be welcomed at any port visited. Shore leave for his crew would take much the same form, whatever the port: the same bars, the same black eyes, the same whoring.

The Captain dreams himself a sweetheart in every port. How mystical, how practical, is he different from any other seagoing individual? Well, hardly.

In the very port just departed the mistress he loves, loves deeply, will already be forgetting him. Another year until Who’s-its return, she will be thinking as she unrolls the bolt of fine silk he has dropped on her bed. Ahead, another he is himself just now beginning to remember.

He loves all of these women, loves them deeply–most of all those that exist only in his head. Over there a port and over there another port and over there a hundred other ports. Such and so many nautical miles to one, to another: scarcely any difference.

Docking is always for him the hard part. He has never got the hang of docking a ship of this size. A junior officer must take the helm. It is good training for them. They like the job. No one suspects.

Except for that curious passenger down in the hole, asleep among the pomegranates: the Captain is fairly certain this passenger knows the score. Their eyes have met.

But the passenger is listless, he exerts no authority. His power to influence matters will not be exercised on this trip. Like any other passenger, Dark is only leaving one place for arrival at another. He desires only a smooth crossing. No storms at sea, no failures in the engine room. Steady as she goes: he wants that.

The Captain pours more whisky into his glass. Shadows flit here and there. The ship rocks, relaxes back, rocks: boards buckle and groan: it knows how it must behave, and the sea too is, for the moment, merciful.

The ship cuts through the waves. It has no doubts. It is not a ship that has known heartbreak. Pomegranates, the ship is thinking. How beautiful.

A seaman sings in the crew’s shower room.

Sometimes I feel, sings the seaman. He sings with a throaty woman’s voice. All hands hold still when the seaman sings in the woman’s voice. They sit or stand alone, heads hanging, bereft and bedraggled, like rags about to be thrown overboard. Only when the seaman’s singing voice dies will they again be swashbuckling men of the sea. An interesting story is told about this seaman whose singing voice is like a woman’s. In Naples, in Odessa, in whatever rough dock bar, in whatever port city he has shore leave, he swaggers into these bars in his thick seaman’s coat, his black seaman’s cap and steel-toed seaman’s boots: he shouts out, And how are all you fine homosexuals this lovely evening?

Sometimes I feel, sings the singer, like a motherless child. But the seaman’s song must wait, since there happens at this time in Dark’s voyage the incident of the seaman who loved walls.

INCIDENT OF THE SEA MAN WHO LOVED WALLS

“What does the wall say? If it is raining, or cold, or a no-nonsense wind blows, the wall says, Would someone please close that window. The wall speaks politely for the most part. If someone arrives with mop and broom it says nothing. It puts on a gloomy expression, not wanting you to note its pleasure. At night the wall stands there thinking deep thoughts. It is prey to nostalgia. Sometimes–not that often, mind you–lust comes over it like a smile over the madonna. The walls have eyes and ears is a line you might have heard. But this is not strictly true. A wall has a nose, though, and smells you as you pass. I’ve heard them sneezing from time to time. There was a wall I once knew which could run faster than you or me or anyone. Certainly faster than other walls. Walls marry each other. They mate for life, just as does the occasional seaman, animal, or bird. If I ever was to fall in love with a wall I would want to marry it. It goes without saying that walls come and go. They go up, they come down: that’s the natural law of walls. A wall will fall on you, if you’re not careful. They would like to, that goes without saying. A wall hardly knows its own strength. Walls hate trees, whereas they have a warm respect for dogs, for cats–cats most particularly. You can hear their giggles, their pride, as a cat walks a wall. Walls are thirsty. They have a drinking problem. A wall is distrustful of other walls perceived in the distance. What’s that wall up to? You will hear this whispered to you as you pass by. Outside walls and inside walls have nothing in common, a fact which may strike you as obvious, but I mention it to you because the matter goes deeper than that. What does a wall say? If it is raining, or cold, or a no-nonsense wind blows, the wall says, Would someone please close that window. It speaks politely for the most part. Walls abominate each other. Wars have been declared. If at the end of these wars no wall is left standing, neither outside wall nor inside wall–of course they are both outside walls now–neither will say it is sorry. They have no regret about being seen as heaps of rubble. Regret is not a word in their vocabulary, which is small. Stop. Go. Listen. Quit that. Give me ice cream. Close the window please. Such as that. They are dense to the point of idiocy, or so claim a number of experts in the subject. They have little ambition. Education, travel, the arts–they could care less. But they’ll comfort you on a cold night. They’ll stay beside you when no one else will. They lead long lives. They rarely fall ill, which is why wall physicians are in such short supply. Death’s walls, however: no personality.”

*

A long way from home, sings the seaman with the woman’s voice. But the seaman now is stepping from his shower, he is drying himself with a thin blue towel: his ears, between his toes, his scrotum. Not in the slightest does he resemble a woman: burly, big-thighed, compact as a discus-thrower. He is humming, he softly hums, but no one has even the smallest interest in his womanly hums. Like I am almost gone, is his hum. A long way from home. Who cares? Shut up. Because there is beginning now the incident of the seaman trickster.

INCIDENT OF THE SEAMAN TRICKSTER

A seaman in the crew’s sleeping quarters does cap tricks. Find the cap, I pay you ten dollars. The cap cannot be found, you pay me one single. How can a party lose? There the cap is on the man’s head. Dollars flutter in every crew member’s hand. The trickster seaman’s arms whirl, he pirouettes along the floor. The arms fall slack. The cap is gone. The cap is nowhere to be seen. His money is collected.

Again, find the cap. Twenty to one, how can you lose? There he stands, under his cap, grinning. Okay, thirty to one, which of you is ripe for the plucking? Bills flutter, every crew member participating. Okay, but this time none of that spinning, don’t spin. Fine, no spinning. The hat is on his head, there it is. Every eye watching. The seaman is encircled by the crew, how can they lose? The man winks, his mouth opens, his tongue darts out. His ears wiggle. The cap remains on his head. He jiggles buttocks, walks a slow circle. Stoops. Stands. The cap has gone. Cries go up. You mean fucker! You cheater!

Find the cap, says the man. Or pay up.

But the crew must search his body. They must remove his every stitch of clothing. He stands naked before them, grinning. No hat. They search the floor, the walls. His cap is nowhere to be found.

“Fifty to one,” he says. “Make it easy on yourselves.” There the cap is on his head.

At midnight he is still going. Crew members have pledged to him their coming year’s wages. Fifty thousand to one, the odds now are. We are desperate. The rules have changed. The capman remains naked. He is bound by ropes hand and foot. He sits on a paint can in a tub of water.

“The trouble,” someone says, “–is with that cap.”

Sure, that’s the problem. What do you mean?

“It’s a what-do-you-it, that cap. An optical illusion.”

“But we saw it. We touched it.”

The capman, a muscular Japanese, sits naked and immobile in his tub of water. Grinning. That cap restored to his head; waiting the next turn.

“Let him do it without the cap,” a voice suggests.

“What do you mean?”

“He starts off capless. No cap. We have the cap. But when he’s done the cap must be back on his head.

This idea is applauded.

“Can you do it?”

“Sure thing. Even bet. My fifty against your fifty.”

I.O.U’s flutter. Every cap of every crew member is removed from the room. The entire crew decides it too must strip. They must all be naked. The trickster’s cap is secretly hurled into the sea.

“Ready?”

“Ready.”

The grinning trickster closes his eyes. His cheeks flare. The tongue darts. The men watch, utterly silent. Nothing is happening. Time passes. Such a long time passes. Every man is aware of the ship’s creaking, of this and that swell, the ship’s roll, the hum, vibrations from the engine room. Their destiny: a year without wages. What will their wives say? How will their children survive? To lose their wages on drink, the long binge, a spell in the brig, this a wife can understand. Such is her fate. But for a cap? Merciless Father, what have they done? But now all is not lost. Something can be recouped from their misfortune. Nothing is happening. The muscular Japanese is sweating. His eyes bulge. The little rat has out-foxed himself. They’ve got the little rat cornered.

“I want to raise the ante,” the little rat says.

“What? “

“Sign over your entire lifetime’s wages to me,” he says, “if I can make the cap return to my head.”

“And what do we get?”

“The satisfaction of learning how the trick is done. You can sign-on on other ships. Make your fortune.”

The crew talks this over. Debates rage. Finally it is decided. They will do it. They scribble these declarations upon scraps of paper.

The seaman’s body turns red, turn’s blue. Muscles ripple. Something is happening along the capman’s scalp. A vague whiteness is there. Something–can it be a cap?–is forming on his head.

Yes, there it is, that terrifying cap that a moment ago was hurled into the sea.

“Pay up,” he say. “Untie me.”

They stare at him. They stare at his awful cap.

Untie me, he repeats.

Not one among them will step forward. How they hate him. He owns their lives, but he is tied there, trussed up like a rat, with his bowl of I.O.U.’s. Finally someone does move. He strikes a match. He holds the flaring match over the assembled I.O.U.s.

The seaman trickster grins.

“Ah, but if you do that,” he says, “I shall own your souls.”

The man with the match hesitates. Seamen are superstitious folk, given to hallucination, rope dreams, dark nightmare. They know the sea is deep, the sky a mystery.

Even now, a mystery is unfolding. The trickster’s bonds are slackening. One by one ropes are falling like dead snakes about his feet. His grin has changed into a thing malevolent.

“The burning would not free you,” he tells them. “Nor would your knives inside my body.”

The seamen know that the man speaks the truth. They are helpless. Their fate is settled. Such is the destiny of every seaman sooner or later. This has nothing to do with disappearing caps. Their lives were never their own. Souls, less so.

*

Morning. One, after so many. Seamen rush about like bodies released from an asylum. Swash this, swash that, wrap rope to a hundred irons. Hurry up now. Gulls, other seabirds, laze in meditation over the ship, over the water, over one another. A bell rings. Whistles toot. Engines seek the deepest bass.

Secure the hatchets. Ready the anchor. Steady now.

Hail, Capitan! What shore?

Passing the Captain’s quarters, Dark sees a hooded figure just then emerging. A start of surprise. The figure is one of his own, though still a novice. Hardly more than a boy. But ardent in his enterprise, eager–Dark sees that. One of the old-fashioned kind. Dark can almost see the scythe in the boy’s hand. From the very air blowing through the cracks around the Captain’s door he can smell the boy’s work inside that room.

The boy at least has the grace to hide his head. He darts past. Then he is on the water, skimming that water to shore: black cloud above the foam.

Dark opens each porthole in the Captain’s cabin. He spreads pomegranate seeds over every space. Full fruits he stashes in the pockets of the Captain’s clothes. Bag after bagful he rolls under the Captain’s bunk. Linked fruit top the Captain’s charts. Dart likes the Captain. He interests him.

The Captain, pallid, stands by his junior officer at the helm. He watches the helmsman’s every move. At the dock a throng of people are waiting. The Captain is old: too many oceans. Soon enough he will know who has come to greet him.

HEART WING

The laboratories.

What guides Dark’s footsteps? How does Dark know? In no time at all he is entering the laboratory grounds. Security cameras, inside and out, might have caught a shadow whipping past. What was that? What? That shadow, there it is again. Well, whatever it was, it’s gone now.

I am death, Dark thinks. I could change you utterly.

Elevators frighten him; he takes the stairs. Locked doors prove no difficulty. Now he strides a long white corridor, shielding his eyes from the glare. So many lights, so much glare.

What is that pulsing? A sign, HEART WING. There to his front, a pair of swinging doors. Another sign, LONGEVITY UNIT. He sees endless aisles, tables placed end upon end, stretching a vast distance, the working surfaces covered with vials, tubes, bubbling liquids, microscopes. Cultures under glass. Workers in identical white tie-ons, most of them stationary, bent at these same tables, at these same microscopes. Scribbling onto color-coded tablets: white, yellow, blue.

His kind.

They work in silence, save for a vibrating hum emerging from the floor, the walls. The hum slows, ceases. He must exist as its cause. All turn now. Some rise, juggle spectacles, reduce a flame, slide one way and another this or that item. A hush settles. All are looking at him. They gawk, they murmur to each other. Smiles replace the quick frown. A few look away, down a far aisle. This or that one utters exclamation. Dark hears a voice–clear, precise, meant to be obeyed: Someone go tell Light her son is here. More whispering: a mutter. But now they are turning away: work calls them. So much work, so many years.

A woman’s heels are clattering. Not clattering, not heels exactly…a subdued sound, in fact, softest rubber. But in this hush, with these ears, in this pulsing, in the absence of the beating heart, every sound is magnified.

And here she is. Here someone is. Running his way. A screech. Another screech: his name. Daaaarrrkkk! The sound goes through him, hits the wall, bounces and echoes. His name. How long since he has heard it spoken? Such quivering in how she calls that name. Such heartbreak, such joy. Over there: a dart of whiteness along a far aisle, now that way, now this!

There she is, here she comes. Smiling, and such a smile. Dark feels his own face cracking open. He is leaving himself, he will fade as a shaft of darkness, a weightlessness of dust sifting beneath the floor.

“You’re here!” she cries. “You’re home!”

Arms enfold him.

Mother.

—Leon Rooke

(“Son of Light” appeared originally in The Toby Press edition of The Republic of Letters, compiled by Saul Bellow and Keith Botsford)

/

/

/

Laura Von Rosk

Laura Von Rosk

The writer and his double

The writer and his double