Market Square, 1986

Market Square, 1986

This is the story of one city, but it’s every city. Struggling with the urban sprawl, de-industrialization, automobile culture, malls, and suburbs, cities all over North America have been fighting for decades against flight from the centre – often finding themselves astonished victims of the Law of Unintended Results. Nathan Storring does an amazing job in this essay of exemplifying the general trend with a particular case, in this instance, the redevelopment, destruction and rebirth of the downtown core in Kitchener, Ontario. He writes: “To me Kitchener’s history is the quintessential parable about the cost that these midsize cities paid to take part in Modernity because we tore down our bloody City Hall. We didn’t have a physical City Hall for 20 years, just a floor in a nondescript, inaccessible office building! It was the ultimate sacrifice in the name of ‘rationality’ – a complete disavowal of any historic or emotional connection to the city.” The beauty of this piece is Storring’s attention to the details – civic debate, architects, planners, theorists, trends, fads. An era comes clear. After reading this, you’ll walk around your town and see it in a different way.

Nathan Storring is a writer, artist, designer, and curator based in Toronto. A graduate of the Ontario College of Art and Design University’s Criticism and Curatorial Practices program, he is compiling a graphic novel depicting conversations that friends, family, colleagues and acquaintances had with renowned urban thinker Jane Jacobs. He is also the assistant curator of the Urbanspace Gallery in Toronto, a media intern with the Centre for City Ecology, graphic designer and webmaster for NUMUS Concerts Inc., and he has been performing archival research for the autobiography of Eberhard Zeidler, architect of the Toronto Eaton’s Centre (among many other things).

dg

.

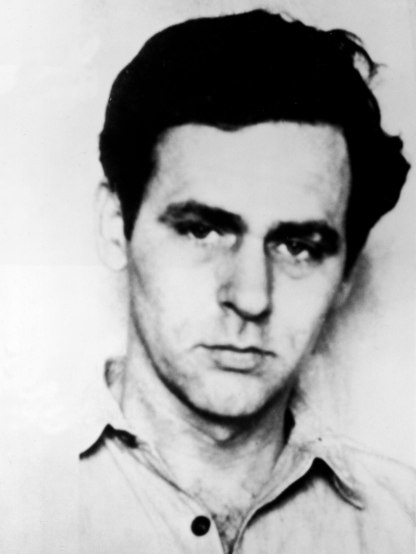

A man dines alone near closed stalls in the food court of the Market Square.

A man dines alone near closed stalls in the food court of the Market Square.

.

Introduction

.

A ruin lies at the heart of Kitchener, Ontario. As one looks East down King Street from anywhere in the downtown core, one will see its gleaming green edifice, its almost-Victorian clock tower protruding above many of the buildings, one of its spindly glass pedestrian bridges stretched over the road like the arm of a yawning lover at a movie. Kitchener’s inhabitants call this shabby emerald city the Market Square – a name it inherited long ago, whose meaning it slowly devoured. The Market Square block bordered by Frederick, King, Scott and Duke Streets once held Kitchener’s Neoclassical City Hall and Farmers’ Market building, but in 1974 both were demolished and the Market Square Shopping Centre was built in their place as part of an effort to revitalize the ailing downtown. The City Hall offices moved into a high-rise office building across the street that was erected as part of the shopping centre development, and the Farmers’ Market was granted a portion of the shopping centre itself, with the primary produce section occupying the parking garage. Today, most of the building has been converted into offices. The City Hall and the Farmers’ Market both have new homes. Only a meagre offering of shops remain, and what is left of the retail area is riddled with dead ends and empty storefronts.

A view down King Street in downtown Kitchener. The green glass clock tower of the Market Square Shopping Centre presides over the cityscape.

A view down King Street in downtown Kitchener. The green glass clock tower of the Market Square Shopping Centre presides over the cityscape.

For many, this ruin is emblematic of the loss of heritage and identity Kitchener endured during the numerous postwar redevelopment schemes that beset its downtown. But could it not be an emblem of another kind? To invoke the architect Augustus Pugin, who erroneously identified Gothic ruins as evidence of a medieval Christian utopia,[1] could the Market Square be interpreted as evidence of a modernist, post-industrial dream that preceded us?

Throughout its history, Kitchener has often imagined big plans for its urban development, but since the 1960s most of these grand plans for downtown Kitchener only ever found form in the Market Square Shopping Centre. Market Square is the most complete and concrete repository of Kitchener’s attempts at re-imagining itself in the postwar period. It is a chimera of styles and ideas – the symbolic and aesthetic laboratory in which architects and city planners forged alternative visions of this city. This thesis is a case study examining the methods by which the city of Kitchener, Ontario attempted to reinvent itself through the Market Square, and what these attempts have left in their wake.

.

Redevelopment: Trojan Horse Modernism in the Market Square

.

John Lingwood, Market Square development, 1974, Kitchener, Ontario. High-rise building that held the City offices on left side of the street, shopping centre and Farmers’ Market complex on the right side.

John Lingwood, Market Square development, 1974, Kitchener, Ontario. High-rise building that held the City offices on left side of the street, shopping centre and Farmers’ Market complex on the right side.

.

The Market Square acted as a flagship for Kitchener’s postwar project to recreate itself as a modern city. Fundamental shifts in the fields of architecture, city planning and economics dictated the shopping centre’s design, and its prominent place in the downtown displayed the importance of these new ways of thinking to the entire city. Its most significant contribution to Kitchener’s modernization, however, was its role as a skeuomorph. Rather than laying bare the magnitude of these shifts, the final design drew on the tradition of the region to recontextualize these shifts as part of a natural, inevitable progression.

.

John Lingwood, Ontario Court of Justice, 1977, Kitchener, Ontario.

John Lingwood, Ontario Court of Justice, 1977, Kitchener, Ontario.

.

The building’s near absence of ornament, its unusual rounded corners, and the choice of concrete as a primary building material in early designs reflected a shift in architectural tastes away from traditional forms. The building’s architect John Lingwood was recognized for his modernist buildings throughout Waterloo Region, including the Ontario Court of Justice (1977), Laurel Vocational School (1968),[2] and the Toronto-Dominion Bank at the corner of King and Francis Streets. Early sketches of the Market Square by the developers, the Oxlea Corporation, depicted the building with a more modern aesthetic than the final product, using cement as the primary building material.[3] One can imagine how Lingwood may have actualized these sketches by observing his work on the brutalist Ontario Court of Justice. Like many other architects in Ontario, Lingwood took advantage of the new materiality and formal freedom offered by concrete.[4] The building consists of several ribbed, precast concrete levels stacked into an imposing facade. Portions of the building are set closer to the street and others set further back like an imperfectly stacked column of building blocks. Such a novel use of concrete in a shopping centre would have had precedent at the time in Toronto’s celebrated Yorkdale Shopping Centre (1964) by John B. Parkin Associates. Regardless, in the final built product, Market Square was built in red brick rather than concrete, though it did retain Lingwood’s characteristic inclination toward austere geometric forms over traditional building types and ornamentation.

To observe many of the modern aspects of the Market Square, however, one must abandon the vision of it as a building entirely and instead consider the shopping centre as a phenomenon of modern city planning. In 1962, then planning director W. E. Thomson declared that Kitchener would have to take drastic and immediate action to ensure the downtown’s continued economic, social and cultural dominance in the region in the coming century. The following year, the Kitchener Urban Renewal Committee (KURC) was formed, and in 1965, after an extensive (though overly optimistic) economic study, they published The Plan… Downtown Kitchener – a document which proposed the near complete reconstruction of Kitchener’s downtown core into a rational, humanist utopia. The conclusions that KURC drew strongly resembled the projects of the Austrian-American architect and planner Victor Gruen, well-known for pioneering the first enclosed regional shopping centre in the United States as well as for his downtown revitalization projects.[5] Like Gruen, KURC recognized that because the city’s suburbs were built since the automobile’s rise to ubiquity, their topology catered to the new needs that this ubiquity presented, such as increased street traffic and parking. Meanwhile, an older downtown, whose design had been set in stone long before this shift, had to find ways to adapt. The Plan proposed that in order for downtown Kitchener to retain its significance in the region, a high-traffic ring road needed to be built around Kitchener’s downtown core, and the core itself needed to become a park-like pedestrian mall with a strict focus on retail activity.[6]

The Market Square Shopping Centre fit within these general goals of the new Gruenized downtown by offering a safe and beautified retail environment that segregated pedestrians from automobiles. The design of the building also embodied many specific city planning propositions put forth in The Plan. Firstly, its enclosed street-like structure alleviated anxieties about inclement winter weather affecting downtown activity.[7] Secondly, it combined multiple uses – retail, offices, the Farmers’ Market and the City Hall – in one development, providing an ‘anchor’ for the central business district.[8] Thirdly, it offered a second floor plaza on top of its first floor roof, overlooking the planned central pedestrian mall on King Street.[9] Finally, it provided new sanitary facilities for the Farmers’ Market and connected the market to King Street.[10] In this way, the initial concept of the Market Square can be seen as an extension of the infrastructure of the street, addressing the concerns of Gruen-esque modern city planning, rather than as a building. Gruen devised similar structures in his own downtown renewal schemes. In his plan for downtown Fort Worth, Texas (1956), for instance, Gruen designed a second floor, outdoor pedestrian area – a “podium” or “artificial ground level” as he calls it – upon which the rest of the central business district was to be built.[11] Gruen intended for his podium to provide people with a place of respite from the noise, smell and danger of automobiles, but unlike suburban solutions to this problem, Gruen’s approach refused to relinquish the density and liveliness of the city. The first Market Square development mimicked this intention on a smaller scale, creating a second floor oasis for pedestrians.

The placement of a shopping centre in such a prominent place in the downtown also foreshadowed a broad shift in North American economic thinking – the transition from a social market to a free market economy.[12] The architectural theorist Sanford Kwinter defines the social market as a society wherein economic activities are embedded in all social activities and directed by cultural organizations that occupy a specific time and place in the world.[13] During the first half of the century, Kitchener followed this economic/cultural model. Its downtown was the region’s centre of economic and cultural life, and there the economy and culture of the area were deeply interwoven. Before the construction of the shopping centre, the Market Square block epitomized this symbiosis of economy and culture. Containing both the City Hall and the Farmers’ Market, it was both a meeting place for political and cultural events as well as a place for the exchange of goods and capital – essentially a descendant of the Greek “agora.” However, by the time The Plan… Downtown Kitchener was published in 1965, the city had recognized that this model was no longer viable in the same way it once was and that something must be done. The new shopping centre that replaced the City Hall and old Farmers’ Market building seemed, at the time, to be a logical solution to this demand for “economic modernization,” or less euphemistically, the emerging demand for a neoliberal free market. In this new paradigm, it was expected that economic activities would be given “freedom from constraint,” both political and social. Initially intended to protect the market from governmental interference, Kwinter argues that this ideal of “freedom from constraint” extends into a social condition in which the market also takes precedence over social practices.[14] In other words, the system of economic activities embedded in social relations that prevailed in the first half of the century had to be inverted, into a system where social relations were embedded in economic activities. Shopping centres epitomizes this subsumption of social relations into the economy. Within the shopping centre, all human activities, transactional or otherwise, are considered within the scope of a financial output. Despite the presence of atriums, seating areas and garden arrangements – social areas that seem autonomous from the shops that constitute the rest of a shopping centre – these apparently innocuous areas are still designed with the goal of stimulating pecuniary activity. Sociologist Richard Sennett describes these areas as “indirect commodification” or “adjacent attractions” that promote shopping by eliding it with other leisure activities.[15]

The City of Kitchener and the Oxlea Corporation were aware that these departures in thinking that marked the fields of architecture, city planning and economics in the 1960s and 1970s may not have been greeted with open arms by the general public, so they appointed Douglas Ratchford, a local painter and graduate of the Ontario College of Art, to find a way to “skeumorphize” and “vernacularize” the building. That is, they challenged Ratchford to normalize these radical shifts for the local population by disguising this flagship building in a skin that referenced the region’s past. Ratchford proposed that the exterior of the shopping centre be built of red brick, rather than concrete as the early sketches intended, and the interior should similarly utilize red brick with garnishes of wood finish on elements such as furniture, appliances and pillars. Furthermore, Ratchford provided the building with a series of Pennsylvania Dutch hex signs painted on five-foot-square wooden plaques, hearkening to the history of the area as a Dutch settlement.[16]

In the first chapter of his book The Language of Postmodern Architecture, the architecture historian and architect Charles Jencks criticizes such use of superficial historical styles in developer architecture as a continuation of the meaningless, impersonal character of Modernist public architecture. Public architecture (exemplified by Pruitt Igoe in Jencks’ opinion) is known for its austere and uncompromising character. The CIAM and other Modernist architects they inspired believed in the ‘universal’ aesthetics of functionalist architecture without any ornament or historical reference. Jencks argues that while developer architecture reinstates ornament and historicism to make their projects more marketable, it suffers from the same impersonal temperament as public architecture because developers make stylistic choices through the statistical analysis of popular taste, rather than through a meaningful connection to their clients or users. Architecture by developers simply decorates the cement slab high-rises or other ‘rational’ forms of public architecture with arbitrary veneers and pseudo-historical ornamentation.[17]

>Ratchford’s skeuomorphizing of the modern forms and functions of the Market Square Shopping Centre fit within Jencks’ definition of developer architecture at face value; however, as a public and private venture, Market Square actually bridged the public and the developer architectural systems, which Jencks portrays as mutually exclusive. The impetus behind the Market Square was twofold: it satisfied the city’s prescriptive ambitions of modernizing and revitalizing the downtown, and it satisfied a developer’s ambitions to generate capital. This type of compromise was a common strategy for mid-size Ontario cities, who lacked the funding of larger cities like Toronto, to pursue the dream of a modern downtown.[18]

Because Ratchford invoked Kitchener’s regional history in his skeumorphic treatment of the Market Square, rather than choosing a more general ersatz historical aesthetic as seen in Jencks’ example of developer architecture, Ratchford formed a narrative between Kitchener’s past and present. In particular, Ratchford’s contribution to the Market Square attempted to smooth out the transition into the neoliberal economic order by placing the shopping centre as the next logical step in Kitchener’s economic development. By appropriating the Dutch hex sign as a design element, Ratchford produced a chronological relationship between the mostly Dutch Mennonite Farmers’ Market and the new shopping centre, which shared the same building. The placement of these signs on both the market and the shopping centre attempted to analogize one to the other, thus justifying and naturalizing the shopping centre as the next logical step in a history of entrepreneurial capitalism, and ipso facto defining the Dutch Mennonite Farmers’ Market as an outmoded form. Furthermore, these signs also falsely suggested that the Dutch Mennonite community (quite literally) gave the project their blessing. Like the old gods of Greek mythology, recast as demons and vices on Christian tarot cards, the Farmers’ Market had been allegorically stripped of its own identity and made to play a part in this theatre of modernization, made to reassure the modern onlooker that history is a process of betterment and that this new development, the shopping centre, was the product of a natural progression.

.

Renovation & Expansion: The Megatendencies of the Market Square

.

Cope-Linder and Associates, addition and renovation of Market Square Shopping Centre, 1986, Kitchener, Ontario.

Cope-Linder and Associates, addition and renovation of Market Square Shopping Centre, 1986, Kitchener, Ontario.

.

Despite the combined efforts of Oxlea Corporation and the City of Kitchener to integrate the new shopping centre into Kitchener’s downtown, other factors such as the small number of merchandisers, a lack of retail variety and poor traffic flow,[19] not to mention the building’s imposing, fortress-like facade that “reminded some of the Kremlin wall in Moscow’s Red Square”[20] led to unsatisfactory profits. So to revitalize the building and fix these initial errors in the building’s design, the new owners, Cambridge Leaseholds Ltd., hired the Philidelphia design firm Cope-Linder and Associates[21] to renovate and expand the Market Square.

In 1986, Cope-Linder gave the Market Square “an overdue facelift” as one reporter put it.[22] The front entrance of the building, originally consisting of a piazza at the corner of King and Frederick Streets as well as an adjacent grand staircase, were removed, and the area they occupied was put under a two-storey steel and glass enclosure, complete with a matching clock tower intended to return a sense of place to the once-important intersection.[23] Two glass-covered pedestrian bridges were also built on the second floor to connect the mall and market building to an adjacent office building and the nearby Delta Hotel.

The renovation did its best to eliminate any evidence of the building’s former identity. It abandoned past attempts at justifying the shopping centre’s presence through pseudo-historical materials and murals in favour of creating a dazzling retail experience similar to those found in the suburbs. Where possible, the re-designers applied veneers or replaced fixtures; they placed new cream, green and baby blue tiles overtop of the red brick flooring, replaced wood railings with brass ones, and so on. The mall’s red brick exterior, which was not so easily muted, was made to look like the support structure for the mall’s new glass frontage, as though John Lingwood had built the brick structure as an armature knowing that the glass would come later.[24] Cope-Linder built their steel and glass addition mostly upon the Gruenesque pedestrian terrace of Lingwood’s design as though it were literally ‘an artificial ground level’ – an elevated empty lot, a neutral plinth to hold their cathedral of consumption. Etymologically, the word “renovation” may be inaccurate in describing the process that the Market Square underwent. It was not merely made new again (renovate = re- ‘back, again’ + novus ‘new’), but rather made to look as though it was never old – always-already new.

At the time of the expansion’s unveiling, the Kitchener-Waterloo Record reported on the event with two counterbalanced articles by columnist Ron Eade. The first article presented the new development as a welcome change from the heavy-handed, Kremlin-wall architecture of the original building,[25] while the second article offered a counter-argument against the renovation by Donald McKay, then Assistant Professor of architecture at the University of Waterloo. Ironically, McKay suggested that rather than opening up the Market Square’s internally-focused architecture with a steel and glass showcase effect as Cope-Linder intended, they had actually created a building that was even more introverted than before.[26] McKay argued that the new glass galleria, complete with 25-foot tropical trees imported from Florida,[27] created “a self-contained, climate-controlled inside wonderland – an imperial concept instead of a complementary one for the downtown core.”[28] Furthermore, he considered the addition “a project conceived by Americans who are preoccupied with protecting shoppers from muggers on the streets – hence the overhead pedestrian bridges so no one need venture outside.”[29] These covered walkways extended the initial impetus of the Gruen-esque raised podium, as seen in the Market Square’s first incarnation, to not only protect the pedestrian from the automobile, but more specifically to protect the middle-class consumer and office-worker against automobiles, weather and ‘undesirables.’

Architectural critic Trevor Boddy terms this protective sensibility the “analogous city,” wherein tunnels or covered bridges between private buildings begin to usurp the public functions of the city street. Boddy argues that passageways that float above or tunnel below the street should not be mistaken for “mere tools, value-free extensions of the existing urban realm”;[30] on the contrary, because they are private space, “they accelerate a stratification of race and class, and paradoxically degrade the very conditions they supposedly remedy – the amenity, safety, and environmental conditions of the public realm.”[31] More pertinently for Kitchener,[32] like the shopping centre, such passageways subject their occupants to the logic of the free market. For instance, in Montreal’s underground city (the most extensive analogous city in Canada), Montreal’s urban planner David Brown observed that many sections of the labyrinth:

effectively screen clientele by keeping a watchful eye out for ‘undesirables’ and ‘undesirable activity.’ Occasionally these definitions may go so far as to embrace all non-shoppers and all non-shopping activity. […] The guards at many locations are instructed to move people along when they have sat for more than fifteen minutes.[33]

All social activity in these ostensible extensions of the infrastructure of the street must yield to economic activity – free from constraint.

.

.

.

.

Left: early proposals for covered sidewalks, K-W Record, 1977; Below: proposal for the King Street

“bubble,” enclosing the entire street, K-W Record, 1981.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In the years leading up to the Market Square’s new addition from 1977 to 1984, the City of Kitchener had plans to build such an analogous city throughout the entire central business district along King Street. Initially, the Chamber of Commerce, led by manager Archie Gillies, began discussing proposals for “an acrylic glass canopy constructed over the sidewalk and attached to building fronts with curved steel beams,”[34] or alternatively, a network of interior doorways connecting adjacent shops directly to one another and overhead walkways (like the ones attached to Market Square) connecting buildings across the street from one another.[35] These ambivalent suggestions eventually coalesced into a single proposal for a massive arcade stretching from one end of the central business district to another.

While this new plan shared similarities with Boddy’s notion of the analogous city, two other architectural typologies also seem to have been at play here – the megastructure and the megamall. Despite still being concerned with the protection and management of pedestrians, megastructures were more intent on controlling architectural form on the scale of the city by treating buildings as units within a larger superstructure. Like a crystal (or fool’s gold), the ideal megastructure would guide any future growth of these units with a set of rules enforced by the superstructure, ensuring a mostly cohesive aesthetic while also allowing for some variation in the subsystems. The strongest synergies between the Market Square, Kitchener’s bubble over King Street and the megastructure movement, however, lie in the movement’s peripheral interests, rather than its central ones. In Reyner Banham’s Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, Banham describes the various theories and projects of this late modernist movement. Very few buildings were actually constructed by proponents of megastructures, and most of the buildings that were finished only partially articulate the tenets of the movement. Geoffrey Copcutt’s Town Centre (1966), Cumbernauld, UK, “‘the most complete megastructure to be built’ and the nearest thing yet to a canonical megastructure that one can actually visit or inhabit,”[36] follows none of the points set out in architectural librarian Ralph Wilcoxon’s definition of a megastructure. It is not truly constructed of modular units, nor is it capable of ‘unlimited’ extension; it is not a framework supporting smaller units, and said framework is not expected to outlive these smaller units.[37] For this reason, Banham begins near the end of the book to describe buildings like Cumbernauld Town Centre as having “megatendencies,” instead of adhering to this rigid definition. In particular he recognizes several high-density downtown shopping centres in English provincial towns that echo the methods and aesthetics popularized by canonical megastructures like the one in Cumbernauld.[38] Like these English shopping centres, Kitchener’s bubble and the Market Square’s subsequent addition are not built to be megastructures, but show “megatendencies.”

Both the enormous scale of Kitchener’s planned “bubble” over King Street and its treatment of public transit echo Banham’s megatendencies. If the arcade were built between Frederick and Water Streets, it would have stretched four tenths of a mile and would have been the largest of its kind in Canada. This plan rivaled the ambition of some of the megastructuralist projects, which similarly occupied vast swathes of land. Also, the immense brutalist facades of megastrutures would often allow transportation to move freely into or through the building, as seen in Ray Affleck’s Place Bonaventure (1967) in Montreal, Quebec. Likewise, part of the King Street arcade was imagined as a transit bay that would allow buses to penetrate the bubble’s membrane.

The carnivalesque atmosphere of the bubble that Peter Diebel, then chairman of the Kitchener Downtown Business Improvement Association, imagined also echoed the idea of Homo Ludens (man at play) within megastructural discourse. Diebel described the climate-controlled contents of the mega-arcade as comprising “jungle-like rest areas, mini golf courses, skating rinks, gazebos, bandshells, play areas for children, fountains and even a waterfall.”[39] Diebel’s dream imagined the reconstruction of Kitchener to accommodate the utopian inhabitants of a post-industrial city, recalling the technological optimism that had been put forth at Expo ‘67 fourteen years earlier: the Expo guidebook promised that with all the wonderful emerging technologies in production, medicine, and computers, “Man is moving towards an era where working hours will be less and leisure hours will be substantially more than at this moment of time.”[40] Many megastructuralists, from Yona Friedman to Archigram, also took this projected transformation into a society of leisure as the point of departure for their projects.[41] While the megastructuralists tended to envision the ludic pleasure of the new urban environment in terms of the malleability and mobility of architecture, Diebel, on the other hand, imagined a more conventional approach, drawing on theme-park-like imagery in his description.

.

A highlighted map showing the area covered by the proposed arcade, stretching from the King Centre in the West to the Market Square in the East.

A highlighted map showing the area covered by the proposed arcade, stretching from the King Centre in the West to the Market Square in the East.

.

Diebel’s dream of the pleasure dome over King Street more closely resembles the megamall’s conception of an architecture designed for the new desires of Homo Ludens, as seen in the West Edmonton Mall (WEM). Like a megastructure the megamall is a building on the scale of a city whose focus is the accommodation of a leisure class (though not an entire leisure society). However, whereas the megastructuralists sought pleasure through a radically adaptive, improvisational architecture, the megamall seeks pleasure through spectacle and simulation. The West Edmonton Mall pilfers Spanish Galleons and New Orleans Streets; it provides wave pools and gardens, but there is nothing radical about the West Edmonton Mall. It simply extends the already well-founded science of mall-making to a massive scale, recycling and embellishing content that can even be seen in a mall like the Market Square (consider the Floridian trees).[42] Descriptions of Kitchener’s proposal for the King Street arcade follow a similar trajectory to the WEM’s extension of basic “mall science” principles, and in fact would have used the Market Square Shopping Centre and the King Centre (another shopping mall built on the other side of Kitchener’s downtown in 1981) as “anchors,” like the department stores of a traditional barbell-shaped regional shopping centre.[43]

Unlike the megamall, which created a utopia of consumption as an alternative to the city, the King Street bubble imagined this utopia of consumption as the city. It superimposed the mall science of the regional shopping centre – designed to produce profit at any non-monetary cost, including the widespread abandonment of urbanity – onto the modernist motivations of the megastructure movement – to create a new society to suit the needs of capital-M Man. This elision of the megamall and the megastructure finds its apotheosis in Michael Anderson’s film Logan’s Run. Anderson used an amalgamation of the Hulen Mall in Fort Worth, Texas and the Dallas Market Center in Dallas, Texas to create much of the megastructural bubble city in the film.[44] For Anderson and the people of Kitchener alike, it seemed as though the consumerist utopia (or dystopia if you are Logan) of 2274, where all production is hidden and automated, was only a step beyond the regional shopping centres of the time.

But like the Gruenized downtown core that never was, this dream of the downtown as a megastructural wonderland ran aground, and its remnants washed up on the shores of the Market Square. Only the beginnings of Market Square’s analogous city – the pedestrian bridges and glass galleria – stand as a testament to this grand scheme of a controlled, connected and protected downtown core. The invasive “climate-controlled inside wonderland” that McKay saw in the Cope-Linder addition to the Market Square two years after the dome proposal was deemed too expensive, represented only a fraction of what Gillies, Diebel and others envisioned for the entire downtown core.

.

Reuse: Junkspace and Jouissance in the Market Square

.

In the years since the Market Square’s last major renovation, its identity has become increasingly unclear. Throughout the 1990s, the mall fell into decline. It endured a recession early in the decade, the loss of the City offices across the street after the new City Hall was built in 1993, the loss of Eatons as the Mall’s anchor in 1997,[45] and finally the loss of the Farmers’ Market in 2004 as it moved into its own building. This most recent chapter in the Market Square’s history, characterized by rapid tenant turnover and constant conversions, has shaken the building’s definition as a shopping centre.

.

Left: the Eaton’s anchor store of the Market Square has now been converted into an office for the K-W Record; Right: rows of exercise bikes currently occupy the food-court-cum-fitness-club.

Left: the Eaton’s anchor store of the Market Square has now been converted into an office for the K-W Record; Right: rows of exercise bikes currently occupy the food-court-cum-fitness-club.

.

The history of Market Square and particularly its final descent into entropy is what Rem Koolhaas terms “Junkspace” – “what remains after modernization has run its course, or, more precisely, what coagulates while modernization is in progress, its fallout.”[46] It twists Kitchener’s dream of the megastructural wonderland into a dystopic parody. Where megastructures attempted to reign in aimless, kaleidoscopic growth by placing it within the cells of a unifying, modernist superstructure, “in Junkspace, the tables are turned: it is subsystem only, without superstructure, orphaned particles in search of a framework or pattern. All materialization is provisional: cutting, bending tearing, coating: construction has acquired a new softness, like tailoring.”[47] In Market Square, spaces have been divided and subdivided with makeshift walls, and in other places once-permanent walls have easily been dismantled in attempts to reprogram the space. Half the food court has become a fitness club; the entire bottom floor of the mall and the old Farmers’ Market area have been converted into offices for a design consultation company.

Because it was once a mall, the Market Square also bears the “infrastructure of seamlessness” that Koolhaas finds crucial to Junkspace. Escalators, air-conditioning, atriums, mirrors and reverberant spaces make the Market Square an interior world autonomous from the surrounding city, and these techniques also constantly strive to disguise the many disjunctures – nonsensically intermingled styles and functions, leaky ceilings, abandoned cafés, elevators that can accidentally whisk an unwary shopper off into the building’s hidden office space. This aesthetic and proprioceptive muzak binds these fragments into a “seamless patchwork of the permanently disjointed.”[48]

Koolhaas defines this mutational, systematic approach to building as the death of architecture and the architect, in a sense: “Inevitably, the death of God (and the author) has spawned orphaned space; Junkspace is authorless, yet surprisingly authoritarian…”[49] Evoking Roland Barthes, Koolhaas insinuates that like writing, architecture has lost its filial origins – its author-God – and has become instead a rhizomatic phenomenon. Furthermore, just as the signifier in the Text has forever lost its signified, the architectural form has forever lost its intended function: “soon, we will be able to do anything anywhere. We will have conquered place.”[50] However, where Barthes sees the death of the author as an opportunity for the play of the reader, who could now engage with the Text unfettered from the singular voice of the author’s intentions,[51] Koolhaas only sees the effect of Junkspace on its inhabitants as “the central removal of the critical faculty in the name of comfort and pleasure.” [52]

.

Left: a bank of TriOS College classrooms, converted from empty storefronts; Right: the courtyard created by the design consultation firm that converted the first floor of the shopping centre.

Left: a bank of TriOS College classrooms, converted from empty storefronts; Right: the courtyard created by the design consultation firm that converted the first floor of the shopping centre.

.

Taking Barthes as a point of reference, could the collapse of architecture into Junkspace not also be seen as an opportunity for the endless play of functional potentials within architectural forms? Because the building’s original program is not considered sacred in the floundering Market Square, some recent conversions have produced playful conversations with the leftover forms of the building’s life as a shopping mall. For instance, TriOS College, which has taken over one bank of shops on the main floor of the mall, exploited the superficial similarities between the topology of a school and that of a shopping centre. They converted a row of shops into a row of classrooms that are now closed to the central walkway of the mall, and converted the utility hallways behind the stores into the new main hallways of the school. Likewise, the aforementioned design consultation company that now occupies the entire bottom floor of the mall, adapted their office plans to the conventions of the shopping mall, rather than adapting the mall to their needs. To accommodate the gap in their ceiling that once served as a balcony overlooking the lower level of the mall, their floor plan includes a central courtyard mimicking the quintessential gardens of the regional shopping centre, such as the Garden Court of Perpetual Spring in Victor Gruen’s seminal Southdale Centre.[53] Like the play of words in Barthes’ concept of the Text, these interventions play on the orphaned post-shopping-mall forms of the Market Square’s Junkspace.

In How Buildings Learn, writer Stewart Brand recognizes the joy of reuse – or the jouissance of play as Barthes might put it – revealing how Market Square’s reuse may yet give the building a new significance. In the book, Brand explores a series of case studies investigating how buildings adapt to the needs of their many tenants over time, and more importantly, which buildings age well and which do not. In a chapter on preservation, Brand discusses the joy of reuse that emerges in buildings when they survive long enough to become well-liked. He quotes architectural columnist Robert Campbell on the subject of adaptive reuse:

Recyclings embody a paradox. They work best when the new use doesn’t fit the old container too neatly. The slight misfit between old and new – the incongruity of eating your dinner in a brokerage hall – gives such places their special edge and drama… The best buildings are not those that are cut, like a tailored suit, to fit only one set of functions, but rather those that are strong enough to retain their character as they accommodate different functions over time.[54]

While perhaps the reuse of commercial architecture lacks some of the romance of “eating your dinner in a brokerage hall,” the Market Square’s character (generic though it may be) continues to shine through in the conversions of its new tenants. They do their best to integrate seamlessly (as Koolhaas’ Junkspace would have it), but ultimately the compromises and “the slight misfit” they produce give them a certain awkward appeal and quirkiness outside of Junkspace’s anaesthetic program.

Furthermore, the mere fact that the Market Square was built to endure may eventually earn it the reluctant respect of its community. Ironically, those solid, imposing walls of the original building that so quickly fell out of fashion may be the complex’s salvation in the long term. Brand observes that a common pattern for buildings that do not adapt well is graceless turnover; a rapid succession of tenants streams through the building without making any permanent contributions to it, until eventually “no new tenant replaces the last one, vandals do their quick work, and broken windows beg for demolition.”[55] However, Brand notes that time-tested materials, like red brick, and simple, adaptable layouts, like that of a factory or the empty box of an anchor store, are one way that unsuccessful buildings are often saved from the wrecking ball. Underneath the veneers and atriums of its addition, the integrity of the Market Square’s design earned it a masonry award for construction excellence the year it was built.[56] This, if nothing else, may guarantee the Market Square’s survival and eventual appreciation.

.

Ruins: Market Square and the Ethics of Re-

.

Thus far, I have intentionally considered the Market Square primarily through a lens of progress. Even in the last chapter on reuse which described the entropy of the current state of the shopping centre, the creative potential of the building has been given far more recognition than the decaying reality. If one wished to, one could easily construct a history of the Market Square as a recurring process of ruination and failure; however, as a resident of Kitchener, I have seen that perspective represented all too often and felt it was important to offer a counter viewpoint of the Market Square as a repository of Kitchener’s utopian aspirations and potentials. That said, it would be naive to not acknowledge this building as a ruin, because this is the position it most often occupies in the cultural imagination of Kitchener.

.

Left: the pediment of Kitchener’s old City Hall mounted above the doorway of THE MUSEUM; Right: the clock tower of the old City Hall as a centre piece of Victoria Park.

Left: the pediment of Kitchener’s old City Hall mounted above the doorway of THE MUSEUM; Right: the clock tower of the old City Hall as a centre piece of Victoria Park.

.

Even from its outset, the project has been a ruin of sorts. In an article written three years before the opening of the Market Square, artist Douglas Ratchford commented that he was surprised to hear about the project because only four months earlier, he had created a painting titled Market Place depicting the City Hall and Farmers’ Market in ruins from the perspective of a Mennonite horse carriage. In the article, Ratchford commented, “I painted it because I think that’s our society’s hang up. The loss of that building is going to affect us more than the people who use it, like the Old Order Mennonites.”[57] His words were prophetic, for this is primarily how the Market Square has been remembered: as “the city’s ultimate pledge of allegiance to the wrecking ball,” [58] as a byproduct of the destruction and deterioration of Kitchener’s distinct cultural heritage in the downtown. Today, the dismembered City Hall building haunts the downtown still; its clock tower sits in Victoria Park and the pediment that sat atop its doors hangs inside the front entrance of a local museum. But even such ruination could have potential.

The art critic and historian Cesare Brandi’s theories of art restoration could be useful as a model for thinking about how architecture could engage with its history. In his article “Facing the Unknown,” historian D. Graham Burnett explains that Brandi believed the only ethical way to restore a painting would be a method that recovered the original ideological content of the painting that had been erased by time, while simultaneously not denying the work as an archaeological object that had been shaped by decay over time, like a ruin.[59] To extend Brandi’s approach, the ideal renovation or reuse of a building would then retain a sense of the building’s original identity, and record the changes the building has undergone since its construction, including decay and the contributions/adaptations of users. But of course, architecture’s relationship to such historical significance is complicated by something art need not worry about – function.

Throughout the Market Square’s history, it has always put function first, in spite of both the identity of the buildings on the block and their condition as archaeological records of decay and change over time. In redevelopment, the City Hall and Farmers’ Market, were completely wiped out and replaced with a new identity – the rationalized and Gruenized market/shopping centre. During the renovation and expansion, in order to improve the functionality of the shopping centre, Cope-Linder attempted to rebrand the building by erasing Lingwood’s design. In both cases, the original identity and the history of change in the building are jeopardized to some extent for the sake of function. Only in the recent adaptive reuses of the building have drastic changes been made while creating a dialogue between the past and present identities of the Market Square, as seen in the design consultation firm’s homage to the Garden Court of Perpetual Spring. While functionality is crucial in architecture, in order to facilitate a sense of shared, built history in a city, renovations and reuses of public or pseudo-public buildings should attempt to provoke a dialogue about the origin of the building or the way that time has affected it.

.

Alar Kongats, Hespeler Public Library expansion, 2007, Hespeler, Ontario. Left: exterior view, showcasing Kongats’ glass addition; Right: interior view, revealing the original Carnegie building inside the glass cube, like a ship in a bottle.

Alar Kongats, Hespeler Public Library expansion, 2007, Hespeler, Ontario. Left: exterior view, showcasing Kongats’ glass addition; Right: interior view, revealing the original Carnegie building inside the glass cube, like a ship in a bottle.

.

In response to this challenge, two buildings come to mind that I believe fully engage with their history, rather than concealing it. The first, the Hespeler Public Library (1923) in Cambridge, Ontario, engages with its origin particularly well through a Brandian approach to renovation. To address his great impasse of how to restore the original idea of an artwork while not hiding time’s effect upon it, Brandi decided that all inpainting must be done using the abstract technique of tratteggio.[60] Thus, when looking at the painting from afar, the viewer could see the painting in its original form, but if he/she were to approach it, they would clearly see that it had been altered.[61] Similarly, the addition and renovation of the Hespeler Public Library by Alar Kongats (of Kongats Architects in Toronto) utilized a form of abstraction to distinguish between the old and the new. Rather than erasing or fundamentally disfiguring the original identity of the building and hiding the process of renovation and expansion that took place, Kongats’ modern steel and glass addition was built around the original Carnegie library. At a glance, the viewer can only see Kongats’ addition from the exterior, but as he/she moves around the building, glimpses of the old facade can be seen through the glass. When the viewer enters the building, nearly the entire original library structure becomes visible. The ceramic tiles built into the windows of the new addition (which serve the practical purpose of lowering solar heat gain) cast the shadow of a broken line onto the old brick facade, as though it were placing it sous rature. It acknowledges the insufficiency of the first building, and yet allows this insufficient element to remain legible. Like with Brandi’s tratteggio, the viewer can oscillate between experiencing the original identity of the library, and the redesigner’s intervention depending on their bodily placement in relation to the object.

.

Rapp & Rapp, Michigan Theatre, 1926, Detroit, Michigan. Partially demolished in 1976, but elements remain to ensure structural integrity of adjacent buildings.

Rapp & Rapp, Michigan Theatre, 1926, Detroit, Michigan. Partially demolished in 1976, but elements remain to ensure structural integrity of adjacent buildings.

.

The second building, Rapp & Rapp’s Michigan Theatre (1926) in Detroit, Michigan, presents a more provocative approach to history. In 1976, the building was partially demolished and the remainder converted into a parking garage. While it does not hermetically seal the building’s origin in a glass cube like a display in a museum, the Michigan theatre fully engages with its own history of failure and decay. It has not concealed time’s decomposing effect on the building or the destructive force that adaptive reuse often necessitates. Koolhaas criticizes architecture for becoming soft and malleable like tailoring, but the ruin exposes the hard truth of building reuse – it comes always at the expense of a partial destruction of the building. I call the Michigan Theatre’s new life as a parking garage a Benjaminian approach to reuse. Walter Benjamin wrote about the evocative character of the ruin in The Origin of German Tragic Drama. As Craig Owens synthesized Benjamin’s musings, “here the works of man are reabsorbed into the landscape; ruins thus stand for history as an irreversible process of dissolution and decay, a progressive distancing from origin.”[62] By leaving a sense of ruination when adapting a building to a new use, the building acknowledges the inevitable and sometimes tragic “distancing from origin” that a building must undergo. In the Michigan Theatre, the tattered 1920s ceiling has been kept intact despite the building’s profound transformation into a parking lot. Furthermore, where walls have been cut to make way for parking spaces, there has been no effort at concealing the damage to the building. This treatment gives a sense of the tragic and sacrificial quality of reuse, the partial destruction a building must endure in order to survive, rather than trying to conceal the process as redesigners customarily do.

These two examples only begin to represent the multiplicity of methods that could be employed to actively engage a building’s history. I believe, however, that they both create particularly poignant dialogues about the issues that haunt all built history. On one hand, the Hespeler Library recognizes the tension between preservation in the face of functionality. On the other, the Michigan Theatre evokes the tragic necessity and inevitability of destruction in architectural practice.

.

Conclusion

.

As factories in Kitchener are being quickly claimed by developers, the city must consider judiciously whether the historical significance of these sites is being retained in these adaptations, or whether these projects are reducing history to a skin no thicker than the murals painted by Ratchford for the Market Square. We must consider whether history is being allowed to exist for its own sake, or whether it is being appropriated to further an agenda, like the Farmer’s Market as a precursor to the shopping mall. As new plans for a light rail transit system declare it will boost positive urban growth in the region, we must listen for the echoes of a modern, utopian downtown Kitchener that never was.[63]

As for the Market Square itself, I hope that the city does not repeat its mistakes and tear down this piece of our recent cultural heritage. It may represent the destruction of historical sites in downtown Kitchener to many people, however that too is a part of our city’s history. Whether we like it or not, history is not always progress. Charles Jencks once said,

Without doubt, the ruins [of Pruitt-Igoe] should be kept, the remains should have a preservation order slapped on them, so that we keep a live memory of this failure in planning and architecture. Like the folly of artificial ruin – constructed on the estate of an eighteenth-century English eccentric to provide him with instructive reminders of former vanities and glories – we should learn to value and protect our former disasters.[64]

Like the iconic Pruitt-Igoe project, the Market Square may have been folly, but it is the most palpable record of an ambitious half-century of plans and compromises, dreams and failures in Kitchener, Ontario, and should be maintained if only to remind us of our former vanities and glories.

—Nathan Storring

Nathan Storring

Nathan Storring

.

.

The story takes place at the Mendelsohn’s apartment one evening in 1941. The central dramatic action surrounds Haller’s visit for Abbie’s twenty-fifty birthday, a party that Abbie says she doesn’t want to celebrate. Haller enters the home carrying a gift, two albums of the

The story takes place at the Mendelsohn’s apartment one evening in 1941. The central dramatic action surrounds Haller’s visit for Abbie’s twenty-fifty birthday, a party that Abbie says she doesn’t want to celebrate. Haller enters the home carrying a gift, two albums of the