An Apology for Meaning, Artist’s Book, Genese Grill

An Apology for Meaning, Artist’s Book, Genese Grill

http://wp.me/p1WuqK-kRQ

.

My real delight is in the fruit, in figs, also pears, which must surely be choice in a place where even lemons grow. —Goethe, Italian Journey

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendacity in the face of what is necessary—but love it. —Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo

In Torino, Italy, once called Augusta Taurinorum in honor of the bull sacred to Isis, goddess of fertility, where Nietzsche went mad, embracing a beaten horse and weeping, dancing naked in his room, and practicing Dionysian rites of auto-eroticism; where, before his collapse, he enjoyed the air, the piazzas, the cobblestones, and the gelato; where the ladies chose the sweetest grapes for this reluctantly German philosopher, it is easy to feel the sensual, life-affirming, Pagan roots of myth-making, to understand those humanistic allegories that sing of life, love, pleasure, and appetite. At the opera, I heard Tosca sing, “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore” (I lived for art, I lived for love). I indulged in long wine-drenched lunches on unseasonably-sunny piazzas, and gazed at gleaming artifacts from ancient times in dark museums. There was a secret restaurant where a small fierce woman named Brunilde roughly took my order, displayed magical cakes with her wide toothy smile, briskly removed the empty plates that once held the most delicious food I’d ever eaten, brought me a shot glass with grapes soaked in absinthe with dessert, if I pleased her by ordering it, but growled me out the door if I was too full or too stupid to partake of her pride and joy. I was in residence at the Fusion Art Gallery on Piazza Amedeo Peyron, presided over by the wise and warm painter, Barbara Fragnogna, who told me about the market across the way which sold beautiful mushrooms, wild strawberries, and bread sticks huge, juicy olives. When I wasn’t eating, or wandering in museums, I was building an elaborate book which folds and unfolds, and is painted and glued and stitched, and “gold-leafed” with foil wrappers from the many gianduji chocolates I enjoyed. I threw off the layers of the Vermont winter to feel the wind and sun on my body, and was reminded of how much our conclusions about what life means are influenced by the relationship between our own physicality and the material world which surrounds us.

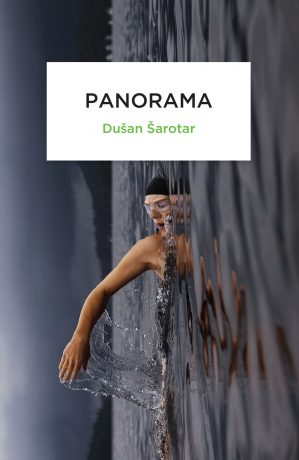

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Meaning is not something that we need to artificially superimpose on the objects and events of the world through some transcendental narrative or morality. It is not something we need to be taught or coerced into seeing by external social construction or manipulative indoctrination. If one is healthy, has an appetite, and senses for seeing, hearing, tasting, and touching, beauty will be everywhere, as “the promise of happiness” or, indeed, in the knowledge of happiness’s fleetingness or absence. We are given the gift of colors and sounds, of textures and of temperatures. And if all else fails, this should be enough reason to be grateful for life. In addition to this inherent meaning, this meaning without thought and evaluation, our intellectual response to the physical facts of the world makes us dream, imagine, and invent ever new celebrations and laments. These expressions will survive and proliferate insofar as other humans resonate with them. And what resonates will be made manifest in real made things, in built places, in enacted experiments. This is a discourse and manifestation over millennia, from the ancient cave paintings to today: humans trying to make sense of the terror and tenderness of the world. We do not despair, we artists and “creative subjects”. Nor do we invent meanings that attempt to twist the facts of nature: Gravity and Mortality are real. Instead, we work with what there is, and endeavor to embrace it in all its fractured glory. Thus, also, the things that we make with our hands, out of paper, pigments, wax, string, fire, earth, water and air, will fade, crumble, dissolve in good time. They are already fragile, already very imperfect, already mostly forgotten. And yet, their fleeting presence is of the utmost importance.

I am sitting on a bench in a church entranceway. A gray, cool, dreamy late morning. Some high school students, girls and boys, gather at the other end of the stone courtyard, gossiping, talking, laughing. Old people, alone, walk in and out of the church. It is a Monday, and most shops here are closed, their metal gratings pulled down. Dirty pigeons coo. In the back streets, a gentle squalor; clothing hanging from lines; abandoned bicycles resting against elaborate gates. On the walls, scraps of political agitation, left and right, shreds of old posters, graffiti scrawls. People talk, but I don’t understand. Markets everywhere, with abundance: artichokes and more artichokes, wheels of cheese, sausages, chickens, lamb shanks, lemons. People smoke and joke, are grim or warm. On my walk here I passed a waitress carrying a tray of espresso down the street from a café out of sight, and a silver piece of paper blew to the ground. I picked it up and handed it to her. Grazie, Signora. An elegant lady walks up the church steps now, in perfectly matching brown and gold, soft brimmed hat with gold trim, a brown cane, brown coat with fur collar, a purse of gold and brown plaid, little brown shoes, dark sunglasses. All her belongings and all her faith perfectly intact from another era. Trucks rumble by; otherwise it is quiet, peaceful. Balconies preserve foliage from the summer, not quite dead, but not quite blooming, vines dangling; a single bruised yellow rose lilts; while back in Vermont everything is covered in snow and ice. This is a life. Anywhere is a life. How different, how similar is it to and from mine, from or to yours? And how does it happen that it evolved to be like this here and some other way somewhere else?

As Goethe noted in his famous Italian Journey, an experience of difference both enunciates one’s individuated self and dissolves it. Visiting another world, you imagine that you might have been, could have been, still might be, sort of someone else, leading a different life in a different country, in a different language, with a different family, lover, children, vocation. Your certainties, the things you took for granted, are called into question. You would be more comfortable not examining them, not questioning: why do you and your fellows do what you do? Are these differences a result of customs, habits, social constructions, error, accident, nature? Are they the result of our upbringing, something atavistic in our blood, or determined by the atmosphere, the landscape, or the history that surrounds us? The external differences—are they petty? Do they alter from the outside who we are inside? Or are they representative of who we are, from the inside out? Ask a novelist or a method actor how much each gesture, each phrase, each seemingly minor choice reveals about identity. The way we eat, how much beauty we need, or how much labor, leisure, love, rigor, sleep, poetry, space, air, skyline, horizon, practicality, recklessness.

And now I am experiencing the differences, the strangeness here in Torino, among people for whom all of this is natural, normal. I enjoy this sense of difference, to a point, as most of us do. We seek it out, we are sometimes sick to death of our own lives and want to gaze at, play at others’ lives; but only for a spell. It can be tiring; one feels alien; sometimes wants to cry out of frustration because everything is so confusing and the simplest things seem impossible; and the people look at you like you are an idiot and you are in a way. You are an adult who does not know things that a child knows.

I get lost often. Sometimes a piazza will have four different entryways with a statue in the middle. Who can remember which way one entered or egressed from? Since I am not usually in a hurry, I wonder why this should matter to me. Maybe because we want always to seem like we know where we are going and as if we already have everything we want. And this has something to do with desire and the desire for love, which is sometimes shameful. As a stranger one wants something. Is looking for something. Has left home to find something that one does not already have. Desire is the need to become one with what is foreign, to take it into oneself and to be embraced by it as well. As Ann Carson tells us in Eros the Bittersweet, we long to be one with the other, but when we have assimilated what was once strange, it is no longer the other and no longer serves its purpose. Knowledge comes only at the cost of desire fulfilled; we can only seek out more and more things, people, places, books, mysteries we do not yet know, have not yet seen or solved or read so that we may experience that supreme thrill of coming to know again and again. We crave difference, but we also cannot keep from looking for likenesses. We seek both everywhere. And the new experiences we have are continually threaded back into what we already know.

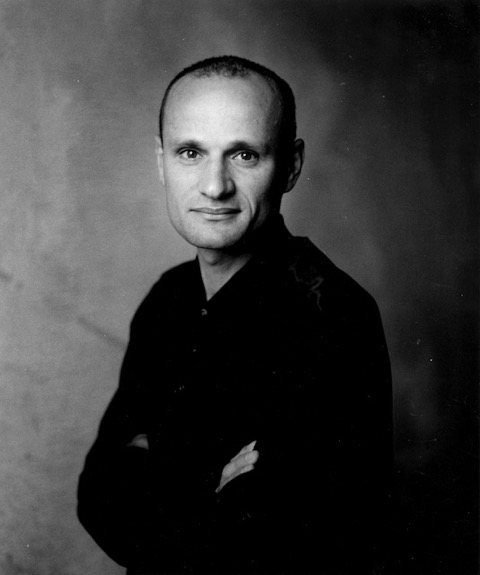

Nietzsche ca. 1875

Nietzsche ca. 1875

In the Egizio Museum in Torino I am astonished by the way the ancient Egyptians had the same instinct for symmetry as ours; for placing each depicted object or vignette centrally within a frame; for aligning each hieroglyph in a uniform square of space; for leaving the most graceful and harmonious negative space between the hand of the man holding a slaughtered bird by its neck and the fronds of the plant in a vase by his side. A sense of what is beautiful, evidently, is at least somewhat natural and universal. And the works of art or ritual made with this sense of what is beautiful still resonates with a mysterious significance, even if we today cannot fully understand or believe in the things that were sacred to the people who made them. Translation across time and cultures is needed for a more thorough comprehension of these artifacts, but something very powerful, something powerfully familiar is present even without a struggle. What we want is to maintain the strangeness, while approaching a comprehension. What we must avoid is to diminish difference in the interest of a complete and total homogeneity.

I am operating in a language I barely know, but I do make myself understood, more or less, with the few Italian words I mispronounce and the few I manage to understand. A good part of the pleasure of communication is in the frisson of partial misunderstanding, in the incommensurable distance between one mind and another, struggling to approximate a shared vision (as in the erotic desire to become one with the unknown). Translation is necessary even without a language barrier, and we all do our best to reveal and also to conceal our meanings from each other. It is a dance. Sometimes clumsy, but sometimes surprisingly beautiful. The differences between language, as Steiner suggests, may be a result of a human need to differentiate one group from another, to keep secrets, to individuate from what may be a basically universal commonality. There are twin drives to compare and contrast, to find analogies, metaphors, likenesses; and to delineate differences, incompatibilities, untranslatables.

Today our basic assumptions about correspondence and difference are paradoxical. On the one hand, there are those who insist that everyone is equal, the same, indistinguishable (or that they should be, were we to look beyond external, physical differences). On the other hand, these same people tend to insist that it is impossible to understand the other; that there are no universals; that there is no shared sense of value; and that language barely helps us to communicate with each other at all, since it is so very distant from the things it claims to signify as to be more deceptive than descriptive. Both of these assumptions depend on a denial of the importance of the physical world; on a denial of any meaningful relationship between nature and cultural norms, between the physical world and the language that describes it; between the human brain and its sensory apparatus; and, finally, between one human brain and another. In reality, things and people are self-similar and they deviate from sameness; but even the deviations do not prohibit some approximation of understanding.

Those who deny difference and simultaneously insist on incommensurability are trying to do two contradictory things at once: 1. to strip away differences that might cause conflict or justify hierarchies or discriminations, resulting in a neutering and neutralizing homogeneity, and, 2. still paradoxically denying that these newly neutralized beings will be able to understand each other despite the pervasive removal of the characteristics that seem to have caused all the trouble in the first place. Perhaps the unspoken hope is that the neutralization and leveling, the moral rejection of the physical world (beauty, ugliness, pain, pleasure, difference) will eventually really result in a homogeneity so complete that, even if we no longer have anything interesting to say or any unique artistic expressions to make, we will at least make no more war, at least harbor no more resentment or hate against the “other”—because there will be no more other. And no differential qualities whatever to get in the way of perfect passive niceness. On the one hand, we are ignoring the inevitable consequences of our neutralizations, neglecting to weigh how much difference makes life rich and strange and fascinating. And, on the other hand, by critiquing conceptualization, deconstructing symbolic archetypes, and undermining the significance of language, we are denying the natural affirmative instinct for finding likenesses and correspondences.

On one level, seeing shapes and patterns where they are not “really” present may be called “pareidolia,” most often ridiculed as a psychosis that sees Madonna and Jesus faces in rock formations and baked goods, endeavoring to prove through argument and scientific study that the piece of fabric housed in a crypt in Torino once was wrapped around no one other than Jesus Christ. The Shroud Museum has rooms filled with “evidence” of why we should believe the shroud belonged to Him: there are blood stains from where the crown of thorns would have been; stains in the shape of wounds suffered when he was tortured, an exemplar of the instrument with which he would have been scourged. The fact that there is just one wound mark where his feet would have been is explained by arguing that both feet were punctured, one atop the other, with but one nail. There is no mention in the museum of the carbon dating done on the fabric, which dated it to a time much later than Jesus’s supposed death; but there is an example of the loom upon which the cloth might have been woven and an example of a crown of thorns, which is arched like a dome and not open like a wreath. Image after image is presented to convince the skeptic that the shroud belonged to Jesus. At first it is hard to even see the shapes that would suggest any face or any body, but, as if one were gazing at one of those magical illusion pictures, if one looks long enough, the desired shapes begin to come into focus—and fade just as quickly into indistinguishable marks again. Desired shapes: the shapes one wants to see.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Fresh lovers often insist that they are “exactly alike,” noting that they both amazingly like chocolate or were born on a Friday as signs that they are made for each other. And even someone as wise and experienced as myself may choose to be deluded into reading into signs that may not be there at all, thinking that the intern at the artists’ residency is making eyes at me, when really he probably just looks at everyone like that. He had told me tales of rituals in his home town where someone would dress up as Dionysus in animal skins and horns, a bag of blood hidden under the pelts, and someone else would chase after him and “kill” him, spilling blood all over the streets. But what did that mean?

Of course, all of our seeing is a process of selecting out that to some extent overlooks the fact that reality is a mass of non-delineated color and light, a mass of shifting molecules temporarily huddled into seemingly distinct shapes and entities. We can question whether the things we see are really rightly to be delineated as separate or if our particular arrangements of what belongs with what or who belongs with whom are comprehensive contextualizations or merely constructed biases, wishful thinking, or limitations. We can say the same thing about words and the concepts that they form—that words are a crime against the multifarious differentiation of reality, that they name and delimit what is really irreducible and unnameable. Names and words and categories pull some things together with other things, leaving other things out, and ignore the qualities of the named and categorized things that do not fit in with the given names—qualities that might render these things more fitting to be named and arranged in different categories altogether. Is the creation of a concept a form of psychosis, hallucination, wishful thinking, pareidolia?

When we note a pattern, say, of bird or insect movement, of repeating forms in nature, in fairy tales, or of habitual actions in our own lives, are we ignoring all of the elements that would render the categorized thing, action, or thought unfitting to be classed within the desired arrangement? Or is there really a way to establish that something is enough like something else to conclude that it is a pattern and thereby attempt to draw meaning from it? Of course, this is essentially the scientific method, but we use it indiscriminately every day, without the necessary “controls” to make our experiments scientifically viable. And science itself is subject to the same kind of criticism: even if its trials are well-documented and avail themselves of responsible criteria for investigation, the scientists have, as we well know, already decided to ask some questions over others, thereby determining what kinds of answers might be found.

But here is the crux: we do all this because we want, we need to draw meaning. And we draw meaning most readily from things that repeat or seem to repeat, from something that seems to be universal or at least not a mere exceptional random aberration. It might be absolutely accurate to say that (at least on a molecular level) everything is everything and thereby all patterns and all names and all conceptualizations are inaccurate and limiting, that the only accurate vision of reality is of a moving mass of colors and light without delineation or individuation. Babies start by seeing that way, but over time begin to recognize (or is it imagine) shapes, distances, faces. Carl Sagan writes that pareidolia itself might be an evolutionary adaptation, since those babies who were able to recognize faces responded to expressions, inducing them to smile, and make eye contact, so that they were cared for, and thus survived. This is rather suggestive, because if we were to consciously try as a culture to repress conceptualization, arrangement, and the meaning-making that rests on this patterning process, we would end up being unable to communicate with each other, and we would simply not survive as either individuals or cultures. Autistic children have a hard time making the kind of eye contact that Sagan suggests was good for survival. And many say that we are now becoming a culture of autism, one in which people do not communicate, one in which people are trapped in their own worlds without the ability to share experience, emotion, ideas. Thus, although the process of making arrangements and making concepts does perforce leave things out, although it may sometimes be inaccurate, although it may sometimes look like psychosis or pareidolia, it is far better to make provisional arrangements and to use language and concepts (always acknowledging that they can change and rearrange) than to exist always in an undifferentiated sea of colors, sounds, and non-shapes, unable to communicate.

But after visiting the Shroud Museum in Torino (the actual cloth is carefully hidden inside its box, only to be taken out on rare jubilee days), I do not believe that the shroud of Turin belonged to Jesus. The form of the body suggested by it is simply not sinuous and beautiful enough to satisfy our mythic desire for him. The image that the experts draw from the bloodstains is of a bulky square-shouldered man, not at all the sweet beloved of the visionary mystics as depicted in paintings over centuries. Just as the scientists who discovered the shape of the DNA molecule knew that they had finally found it because the double helix was the most beautiful configuration, so we can see that the shroud did not belong to the son of God because of the gracelessness of its traces.

Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

There has to be a difference. Difference is thrilling, is frisson, is friction. If there were no difference, no distinction, no discrimination, no delineation, we would see nothing. Everything would be one blended morass, one moving, shifting mélange of everythingness. No shadows, no lights, no textures, no patterns or deviations. So we like to go away, discover new things, challenge ourselves, compare and contrast the familiar against the strange in order to understand, again, our expanded selves. And yet we find ourselves in a constant emotional oscillation, a cycle swinging between comfort, tedium, restlessness, curiosity, desire, risk-taking, danger, exposure, discomfort, exhaustion, home-sickness, comfort, tedium…ad infinitum.

Thus we come to the necessity of maintaining some borders at a basic level, personally, and then globally. We need secrets, mysteries in order to remain where we are, among our fellows in our homes, in our romantic relationships; or else it is as if we were running rampant around the neighborhood, around the world, continually searching for newness, making so many things the same as we unite with them, making everything homogeneous and known all too quickly. A promiscuous lover is someone who has not learned how to mine the depths of himself and his beloved; is quickly bored; doesn’t have enough inner resources to discern the depths hidden in his lover; thus he moves on quickly in order to stimulate his poor imagination. Curiosity, desire, conquest of new ideas and intellectual territory, all have their value: but they should not be gluttonous. If we are to feast, let us leave time for regeneration of resources; let us make sure we properly savor what we are sacrificing and devouring. The communion of the self with the other cannot be celebrated so swiftly that all differences are leveled out, sanded away, consumed by the Moloch of desire for newness. This touches on the problem and pleasure of materiality. The basic limitation of resources; that they are not infinite. You can melt down idols to make new ones, but then the old idols no longer exist. How can we contrive to keep the old ones and erect new ones, too? Of love we can barely speak in this regard: the old lovers are replaced by new ones, yet they remain, one hopes, still within us, and we within them, in traces, some very potent, as we continue to consume and appropriate and expand, becoming new ourselves and shedding strangeness as we go, exploring our anti-selves, the characteristics we harbor that are anathema to our primary identities and the identities of our native lands and cultures.

After writing The Sorrows of Young Werther, and serving many years as advisor to the Duke of Weimar, Carl August, Goethe “stole” away at three in the morning, from his friends, his duties, and his romantic (but non-sensuous) relationship with Charlotte von Stein, to sojourn in Italy for two years. There he found himself in contrast to the differences he experienced, searched out the ancient remains of classical Rome, learned about architecture at the foot of buildings designed by Palladio, learned to see by looking at Italian paintings, developed his concept of the universal Ur-Pflanze from which all plants metamorphose (Alles ist Blatt), and enjoyed, above all, the weather and the fruit. His wonderful account of his adventures includes detailed descriptions of the geology, flora, and fauna of the countries he passed through), along with evaluations of artifacts, architecture, painting, and peoples (he burdened down his pack with rock specimens as well as heavy books). Referring to the Greek god, who could not be conquered in wrestling matches as long as he remained in contact with his mother, Gaia, Goethe writes, “I see myself as Antaeus, who always feels newly strengthened, the more forcefully he is brough into contact with his mother, the earth”.

The Germans have always harbored a romantic longing for the physicality of Italy, “the land where the lemons bloom,” as Goethe writes, as mythic antithesis of everything Germanic (stoical, cold, disciplined, abstract). Nietzsche sojourned to Torino, a Dionysus on the River Po, in conscious ex-patriot spirit. What meanings did he find there, that philosopher with a hammer who famously denied the existence of “Das Ding an sich,” and called on us to bravely consider the abysmal probability that there is no meaning or purpose to life whatsoever? He certainly meant that there was no predetermined meaning or God-given purpose, no purpose ordained by a God. But he did not mean to repudiate the ways in which the world can be meaningful (affirmed, celebrated, enjoyed). For his rejection of the “thing in itself” was decidedly not a transcendental call to celebrate merely the disembodied life of the alienated mind out of touch with the physical world (a thing in itself, surely, despite Berkeley’s skepticism, and despite the inability to know it absolutely or objectively beyond phenomena). Here in Torino, this city so beloved by Nietzsche, while I am struggling with the question of meaning, I feel compelled to come to terms with him on this question. We are in agreement on the central importance of the material sensuous goodness of the world and on a deep suspicion of any ideologies which aim to affirm something in contradiction to the facts of this real.

Goethe by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1828. (Public domain)

Goethe by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1828. (Public domain)

Ecce Homo, which he wrote while in this city, begins with a serious discussion of the vital importance of digestion, weather, and music, all experienced by Nietzsche (and clearly by Goethe as well) as fundamental physical requirements for living the right life. The theological-metaphysical questions are deemed unimportant at best, treacherous deviations at worst. Thoreau, whose first chapter in Walden is called “Economy,” planted beanstalks as the most efficacious conduits to a realm where one might best consider “higher laws”. It makes one wonder what would have happened to Thoreau had he visited Italy (he traveled a great deal, he noted, in Concord). Would he have abandoned his dietary restrictions against drinking coffee? Might he have succumbed to the animal spirits and fallen in love? Margaret Fuller, who translated that comprehensive man of spirit and sense, Goethe, complained about the disembodied tendency of her friend Emerson (and Thoreau was even less sensual than his mentor), did travel to Italy and fall in love, gave birth to a probably illegitimate child, and participated in the Italian revolution. If she had not tragically drowned on her return home, she might have infected all of Concord with a new European sensuality! Just imagine. Nietzsche, who admired Emerson greatly, who was just about as abstemious and celibate as Thoreau, still knew how to reason from the hands to the head, as the bard of Concord counseled—and from the stomach too, though, it would have to be a strong one.

Love of Fate meant for Nietzsche a love of life exactly as it is, which seems to suggest a belief in a thing in itself after all…the world in itself, as it is—mediated by our senses, our tastes, our interests, our desires, yes, but not subject to utter transformation of its basic realities: mortality, gravity, pain, beauty, brilliance, energy, stupidity, music, pleasure, illness, cold, sunshine. Darwin explained all of this in his own way. We don’t live in a friendly universe. The world cares not a fig for our personal happiness, though our genes may well fight mightily for their own generation. And the connection to Spinoza, greatly admired by Nietzsche, may be helpful: the world was not made for us humans, and thus should not be judged according to how well it does or does not serve our aims and desires. The world is good in itself. Is god, is divine in itself, whether we are experiencing petty miseries or committing atrocities. The world is beautiful, even without the concept of beauty invented by humans. We are to look at the world from the “perspective of eternity,” which is not a transcendental perspective, but, rather, one which provides an angle beyond our own particular immediate interests. Objectivity? Well, not quite. With Nietzsche we can speak of a perspective from the mountain top, as far away from the flatland as possible, but with a knowledge of the subjective world of taste and senses. Nietzsche writes, in The Twilight of the Idols, “One would have to be situated outside life, and on the other hand to know it as thoroughly as any, as many, as all who have experienced it, to be permitted to touch on the problem of the value of life.” For, if our reflections seem all-too mercurial, shifting, and arbitrary from the perspective of eternity, closer up they are instinctive and healthy tastes, responses to and engagement with the world.

As subjects, creative subjects, we make of this world as it is what we can. We cannot help but make meanings about it. But let these meanings be in metaphoric harmony with the real facts of nature. Let us make and preserve myths which help us to understand, to celebrate and to weep over the true facts of human existence, and its true pleasures and pains. Gilgamesh is struggling with the death of his friend. He searches for a way to be immortal, to conquer death. But when he thinks he has found it, a snake eats the magic herb he has foolishly left on the shore while he swims. Thus, although humans must be mortal, a snake can continually shed its skin. A true myth. The kind of fiction that Nietzsche railed against was of another kind: a false fiction, one that repressed the reality of death, repressed natural instinct and pleasure, repressed sexuality and the will to power, repressed beauty and energies and great health and desire in the interest of a transcendental Idealism offering an afterlife, and some sense of pious righteousness in exchange for all that made life meaningful. The myth of Christianity he would battle with the myth of the beautiful drunken god: Dionysus versus the Crucified One. Thus, he aimed, not to do away with all myths (that, in fact, was Socrates’s great sin, according to Nietzsche), but to celebrate the myths that are in accord with the true facts of life. Steiner quotes a cryptic passage from Nietzsche’s notebooks: “God Affirms; Job Affirms.” And glosses that Nietzsche was referring to his idea of the aesthetic justification of the world. The world of wonder and beauty. Look at what I made, says God to Job. I made the Leviathan. I am an artist. Don’t talk to me about your petty troubles.

And here in Torino, Nietzsche, enjoying a rare respite from his chronic pain, in withdrawal from Wagner, the Wagnerites, the Germans and their obtuse Idealism and Morality, enjoyed the sunshine and the air and the food and the gelato (but not the wine); enjoyed the graciousness of the people; and the lightness of Carmen (Torino was “tutti Carmenizzatto”). The world that Nietzsche celebrated was not so much a world of the future, a world of future higher men, but a revival of Renaissance and Pagan values. Not at all the postmodern insipid relativity of values with its snide rejection of beauty, nobility, genius, aristocratic individualism.

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Meaning has been attacked from two sides: on the one hand by the commercialization and commodification of life, by the simulacrum covering up an abyss of shallowness and the emptiness that is left over after the orgy of sensationalism, as humans become more and more bereft of any real connection to nature, human relationships, history, culture, beauty, pleasure, divinity, sacredness. On the other hand, it has been attacked by the cold lizards of theory, who feel nothing themselves but only touch us with their clammy hands so that we too feel a chill and cannot sense the heat in what naturally should move us. These theorists even dare to claim Nietzsche as their own. Because he questioned the idea of a transcendent meaning, aiming with his iconoclastic hammer at the ideology that denied the real meanings of the world, they use his words as an attack on meaning altogether. Because he called for a transvaluation of values, they use his words as an attack on values altogether, missing his joyous celebration of the values of nobility, of the Renaissance, of ancient Greece, of great art and great men, of genius and beauty and rapture. Indeed, he had a hammer (though sometimes it was a tuning hammer for a piano, not a bludgeon), and there was smashing to be done. He was a great destroyer, who called himself “Dynamite.” But he destroyed only as a preliminary to creation. The epigones took up his hammer and began smashing even the idols Nietzsche himself had venerated. They smashed veneration altogether. And in their adolescent giddiness, in the din of their mob fury against what was once great, in their ressentiment, they did not hear the most important part of his message: the axes must be turned into chisels, to carve new idols, new values, new words, new forms, new metaphors, ones that honor what is vivid and beautiful in life, ones that affirm the instincts and the senses.

In a museum in Torino I saw a painting of Santa Lucia, her bloody eyes on a plate. She was a good pious girl, promised in marriage to a pagan, whose mother was ill. She was called by an angel to devote herself to Christ instead of the Pagan fiancé, and in exchange, her mother would be cured. She willingly did so, refusing to bow down to the Emperor, and giving her dowry to the Church instead of her future husband. For this, some say, her eyes were gouged out. Or else she cut them out herself so as not to be attractive to her husband-to-be. She is lovely and fierce in the paintings, and probably the man they had chosen for her was a brute and not to her taste; and her devotion to Christ healed her mother; but can we not think of a better story for her? Is this really a model worthy of imitatio? So many of these maiden saints, who refused arranged marriages and gave themselves to the disembodied fantasy of the beautiful, scantily-clad Christ instead, were exercising the only power they had, and for this they are admirable. They found, by these religious subterfuges, one way of protecting themselves from drunken brutish masters in the form of husbands, pimps, and fathers. But their virginity was no great prize. Can we not imagine stories for them with better endings? Lovers to their tastes, freedom to choose, to adventure beyond the convent or house-wifely walls? Instead of continuing to venerate the lives of these pious girls, we would do well to imagine new vitae for them, lives lived in rebellion, not against Pagan Emperors and sexuality, but against the control of their bodies and souls by male authority figures, lives lived in full flowering of their sexuality and pleasure-loving instincts, in celebration of female desire. We must make new saints, and also revive old models worthy of veneration from the archives of history, woman and girls who knew light and dark, pleasure and pain, flesh, the devil, and the divine sweetness of the embrace of a beautiful, living beloved body. Poor Santa Lucia. We pity her and regret the loss of her beautiful eyes. And then, in her honor, we go looking for traces of other myths or at least a few fallen figs from some controversial historic feasts, to savor from the safe distance of a relatively tame and unromantic time.

Painting of Santa Lucia, Syracuse Italy

Painting of Santa Lucia, Syracuse Italy

I am on my way to Gardone Riviera, on a pilgrimage to visit Il Vittoriale, the monumental house, shrine, and garden of Gabriele D’Annunzio, Italian novelist, poet, patriot, lover, and aesthete. When I mention him to people here they sometimes seem uncomfortable; because he was wild enough to disregard the Treaty of Versailles and take over the island of Fiume to turn it into an artistic utopia; because of his relationship with Mussolini; because he represents or seems to represent many things that are nowadays in bad odor. To get there I have to take a train to Milan and one to Brescia and then a long bus ride.

It is a misty, cool, warm morning in February, and confusions proliferate: about trains, ticket machines, banks, language, customs. They seem to do everything differently here, but for them that is how it is done. Then I realize that even in my own milieu I am strange. That I am strange, wherever I go. An artist is outside of society, but also very inside it. Inside of life. Observing, but also feeling through and for everyone and everything. After writing that down I wonder if it is arrogant, as if I were suggesting that regular people don’t feel, are not conscious. No, it is not that, but rather that their attention is mostly elsewhere, and ours is so often concentrated on reflection, on the symbolization of everything. Watching gestures and configurations, listening to emphases and choices of words, noticing formal variations and repetitions. As Suzanne Langer notes, to use symbols (rather than just signs) is to talk about the world, not just to denote it, not just to deliver information, but to consider how things are, and even why. And as artists, our lives are consumed by symbols and symbolic interpretations. The entire phenomenal world is to us a sort of symbol-picture of something else. No, not of another world, as Plato would have it; not a bad copy of some perfect original, but actually a symbol-complex of itself.

The phenomenal nature of the physical world means to us. But we don’t make of it what isn’t there, but see in it all that there is to be seen in it. Well, not everything at once—that would be too much, that would be a jumble. But we see many things, one after the other, from different perspectives, in correspondence; we have many ways of seeing meaning in what is. We are curious about how things are made; where they came from; how they were invented; what human need they answered; what history they contain; what natural materials; what natural miracles are evident in their existence; what they tell us about human and animal life, past and present, about desires, fears, curiosities, mistakes, kindnesses and cruelties, despairs and foolish hopes. Thoreau, allegedly an arch anti-materialist, collected and used objects to trace history… as artifacts of material culture, looking, always, for the law and the deviation. Goethe, a naturalist and collector of botanical, geological, and artistic specimens, traced the variety of the plant world back to one original Ur-Pflanze, and then envisioned the entire world of objects and behavior as an allegory for this constant development, this constant Becoming (Werden), from out of the essence of Being (Sein).

All artists mine objects, physical acts, stories, events, speech utterances, places, buildings, man-made and natural, for their significance, for traces of how and what we have dreamt of and done battle for; for their own qualities and also for the way in which they are allegories for other things, feelings, events, experiences; for the way they seem to echo and repeat. When we see repeating patterns we naturally sometimes think we have learned something about life, some tendencies or natural laws…and, despite the doubts shed upon such instinctive correspondence nowadays, often it is true. But it would be foolish to take only one or two experiences and construct a final story about life. The largest, broadest vision would be necessary to oversee all the conflicting narratives before coming to any conclusions. Life is brutal, life is tender. Humans are brave, are craven; are polygamous, monogamous; people of habit, craving change; we like to deviate and to stay close. So, whenever we try to maintain just one thing we discover another side or possibility, but not to the extent that everything cancels everything else out. We may still come to provisional conclusions about the nature of the world, society, our lives, about what works and what does not; in fact we must. But let these not be rigid or polarized, let us not base hasty conclusions solely on either the sum of the good or the sum of the bad experiences. A little hope is healthy, as is a touch of denial, since sometimes things turn out better than one expects, even in the worst of circumstances. As much horror as there is, there is also always good. Neither can be cancelled out by the other. We must see it all. Read it all into what we find before us. Find a way to embrace it all. Amor fati—Love of fate.

I arrived at Gardone Riviera too late in the afternoon for a tour of the house, so began my visit to D’Annunzio’s Il Vittoriale degli Italiani with a sunset stroll around the “most beautiful garden in Italy”. From my Neo-Classical hotel, with its palm trees, classical columns, and reproductions of Roman sculptures, I walked up the steep winding paths and stairways to the grounds, past little houses perched amid orange trees and covered in vines, until I found the gate and entered D’Annunzio’s strange dream: grottos with idols; walkways beneath portentous archways; a sudden St. Francis of Assisi; a fountain encircled with gorgon heads; a lofty monument to the heroes of Fiume; a giant boat docked on land; columns topped with statuesque nudes. A sign before a sun-dappled little garden made up of rocks, small columns and upright missiles, informs the visitor that this is the most sacred spot of all. The “little lake for dancing” is at the bottom of a steep ravine, reached only by winding down hundreds of small stone steps. The large amphitheater is encircled from behind by tall cedars and the snow-capped Alps, and its stage has a gleaming Lake Garda as its backdrop. I imagined Isadora Duncan, one of D’Annunzio’s many lovers, walking there—as if on the water—in consummate Classical grace.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

That night I wandered around the out-of-season resort town, looking for somewhere to dine, lighting upon Caffe D’Annunzio itself, one of the only places opened, where three or four locals were crowded around a counter drinking wine. I nursed a negroni on the closed-down patio while wondering what Il Vittoriale means. Why, I wondered, should it make us uncomfortable? D’Annunzio had a sense of the heroic about him that is out of fashion today. A sense of superiority and sacredness, a will to power, a contempt for lowliness, sickliness, vulgarity, cowardice. People may mock D’ Annunzio’s mythologizing, moralistically decrying his frequent bad behavior, I think—or perhaps this is the gin and the absence of a restaurant—, but at least his impulses were signs of life, of appetite. D’Annunzio might well be censured or ridiculed for his celebration of militarism and his association with Mussolini , for his many lovers (whom he adored, but also treated atrociously), for his many dogs and his race cars, for the consciously elaborated mythology of himself as a demi-God, for a combination of wounded pride and delusions of grandeur—except that he was a great writer, and his grand lifestyle enriches our collective imagination.

Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932)

Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932)

Compared to the lukewarm morality of today, our smug conformity and communal piety, D’ Annunzio’s mythic theatricality exercises a certain attraction. Considering all of this, I found myself laughing out loud at the mad, mad world, strolling on the closed-down boardwalk. I was dwarfed by a 19th century edifice, crowned with a bright yellow Renaissance-style tower with the words GRAND HOTEL emblazoned in golden-tinted mosaic. It was a huge sprawling place where Churchill and Mussolini, and many other mortally-flawed heroes and villains stayed. Like most everything else here, the historic hotel was boarded up until May, and the boardwalk was surreal, empty, but for a lone palm tree swaying on the promenade. In my drunkenness, with the help of a kind stranger, I managed to work the cigarette machine I found on the way back to my hotel, and smoked a rare cigarette—which, in its rareness, got me even higher—and wondered about the difference between aesthetic individualism and fascism. The cigarette, in its naughtiness, helping me to flirt with the decadent charms of immorality.

Aesthetic individualism is associated with culture, beauty, delicate sensibilities, the collection and preservation of fragile artifacts, and an internationalism that revels in the multiplicity of the creative imagination; fascism is nationalistic, collectivist, brutally destructive, anti-intellectual, a danger not only to human beings and their ethical freedom, but also to the beloved precious buildings, artistic and historical artifacts so admired by the aesthetic individualist. So why would they ever, why do they sometimes keep common cause? In the case of D’Annunzio, we have a man of letters whose only real political affiliation was with the Party of Beauty, but who in fact did collaborate with a man who would subsequently become a fascist dictator. But even before Mussolini came to be Il Duce and to be called by D’Annunzio “an evil clown,” their relationship was strained. They came together at the start of World War I, over a shared vision of a new Roman Empire, a romantic ideal that called for the re-annexation of Trieste, Fiume, and other territories that had once belonged to Italy and which, they both agreed, should once again be theirs. D’Annunzio roused his countrymen to enter the War and to defend the French culture under siege, with speeches and street theater, and fought on the front lines. But after the Treaty of Versailles failed to reward the Italians for their sacrifices in the war, he took history into his own hands, and, with a ragtag militia, easily took Fiume back for the Italians, to the cheers of the mostly Italian populace, and tried to found an artistic utopia with a democratic constitution there. Mussolini kept himself scarce and watched from afar as the dream foundered over the course of a little more than a year, only later to seize Fiume from the Austrians himself, this time, much to D’Annunzio’s displeasure, to make it part of a fascist state. The fascists were frequently embarrassed by D’Annunzio’s eccentric sybaritic antics, his poetry and his displays of what they considered “feminine” voluptuousness; his nude sunbathing and worship of art. His association with workers’ collectives agitating for unions and civil rights also complicated matters. When D’Annunzio was not being swayed by the democratic socialists, or being lured into shady dealings by the fascists, he was doing whatever he fancied, collaborating with composers on operas, writing plays for his lovers, writing sumptuous novels and books of poems about his lovers, spending money he did not have on beautiful books and objet d’art, and making love. He felt that Mussolini had abandoned him at Fiume and that he did not give him the credit he deserved for bringing Italy into World War I; but Mussolini the dictator saw to it that a national edition of D’Annunzio’s complete works was published and that the extensive quixotic renovations of Il Vittoriale be funded in part by the Italian government. D’ Annunzio, in turn, dedicated his house and grounds to the Italian people as a monument to the soldiers who dared to take Fiume with him. It was also a retreat. Although he had dabbled sensationally in politics and war, he was, by nature, an aesthete who enjoyed comfort and sensuality. Luxury, he wrote, was as essential to him as breathing. He liked to sit at the feet of lovely women, and shower them with flowers, leaf through ancient leather-bound books and recite poetry in the dark. Over the course of a five year period, he once wrote over 1000 letters to one woman alone. They don’t make men like D’Annunzio anymore. In the mostly empty dining room of my hotel, there were none to be seen, so I gave myself to a large piece of black forest cake with whipped cream, and the conversation of the owner and his friends, who tried to get me to drink more and more champagne and spoke to me in a mixture of broken English and mostly incomprehensible Italian. Somehow I stumbled upstairs alone, somewhat nauseous, and had a nightmare about D’Annunzio. Or was it a dream?

The following day I made it into the sanctum sanctorum, D’Annunzio’s house. In the entryway to what he called “the Priory” stands a column to divide the guests into welcome and unwelcome. The many creditors would have to wait on the right, the women, mostly artists and poets and actresses, would be ushered in on the left to a room filled with incense burners and a helicopter blade hanging from the ceiling. The lucky ones would be brought to the music room, cocooned in dark tapestries. D’Annunzio had lost an eye in the war and was sensitive to light. Besides, music requires concentration of the mind. The floors are covered in carpets and pillows, for lounging or making love; busts of Michelangelo and Dante, his ‘brothers’, stand like witnesses. Books and music folios line the walls, surrounding life masks, sculptures, lamps of blown glass fruit, leaded windows, an organ, lyres, lutes, bells. The predominant tones are red, gold, and black. From the music room we proceed to a writing room, with a large desk, where D’Annunzio died, and a medicine cabinet filled with drugs. Over the doorway from the writing room to the bedroom, we read: genio et voluptati —genius and voluptuousness. The bedroom is called The Room of Leda and overflows with chinoiserie and silken fabrics and cushions. But genius is not all pleasure and happiness. Consider the Leper Room, for meditation on the death of his mother and Eleanore Duse, which features a bed in the shape of both a cradle and a coffin, “the bed of two ages”. Two leopard skins are draped over the steps leading down from the bed. A painting of Saint Francis embracing the leper hangs near the bed. We are to understand that D’Annunzio considers himself a leper in the eyes of society, in exile here after his failed attempt to raise life to its rightful gloriousness despite the philistine, luke-warm good behavior of his fellows. In his Italian Journey, written back when words like lofty, harmonize, exalt, true, and noble could be read without embarrassment, Goethe commented on the poor reception granted to a number of Palladio buildings:

How poorly these choice monuments to a lofty spirit harmonize with the life of the rest of mankind…it occurs to me that this after all is the way of the world. For one gets little thanks from people when one tries to exalt their inner urges, to give them a lofty concept of themselves, to make them feel the magnificence of a true, noble existence.

Alas, Goethe saw the tendency of things, already at the end of the 18th century. Though I wonder what he would have thought of D’Annunzio’s taste. The Relics room is a syncretic temple to all religions, mixing sacred objects with profane military paraphernalia. There are elephants, bronze Buddhas, medieval crosses, rows and rows of Catholic statuary, and a Fiume flag on the ceiling. Over the doorway is written: “Five Fingers, Five Sins”. Out of the original seven, D’Annunzio had excluded lust and greed. These two were not deadly sins, but virtues in his creed. A broken steering wheel on the altar, which once had belonged to an English racecar driver friend, symbolizes the religion of risk. His workshop, the only room in the house to let in natural light, can only be entered by prostrating oneself beneath a low ceiling and taking a few small steps. The writer had to humble himself before his muse, his great love, the actress, Eleanore Duse, whose bust sits upon his desk, covered with a silk scarf so her beauty would not distract him from his work. La Duse, as she was called, earned the full adulation that Il Duce was denied.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

D’Annunzio called his house “the book of stones,” and like all good books it is filled with symbols. Everything means something. And the many mottos written on ceilings and round the rims of rooms and over doorways help us should we falter in our interpretation. And yet, I probably will be trying to understand it all for a long time to come. Certainly, although it would be simpler to outright reject grandeur and beauty, because of its sometimes questionable provenance, I cannot moralistically deny myself the intellectual and sensual pleasure it brings. And yet, the provenance and history of objects is significant and fraught with tangled skeins of so much seeming good with so much seeming bad. I will continue to be curious about all the life and the history that can be gleaned from material remains—portals to other worlds and times—and to embrace the wild contradictory nature of humanity with an amor fati—love of fate—communing, even if need be, in occasional discomfort, with all kinds of ghosts, neither assuaging nor simplistically censoring the transgressions of these haunted spirits.

What would D’Annunzio have thought, however, had he known that the souvenir shop outside the grounds would feature not only snow globes with little miniature Il Vittoriales and coffee mugs emblazoned with his face, but also a section devoted to his special friend and nemesis, Mussolini, offering brass knuckles and ominous riding crops for sale? Would he have approved? I would like to think he would he have considered it an impudent intrusion, actuated by purely capitalist vulgarity, a treacherous re-writing of his more nuanced story, rather like the posthumous revision of Nietzsche’s biography by his Wagnerite sister. (Elisabeth-Forster Nietzsche, as is well known, attempted to posthumously present her brother as a proto-Nazi, he, who in reality despised the Germans and who called in his last days for the death of all anti-Semites. The Mussolini display made me feel queasy, so I quickly exited the little shop and walked down the hill to beautiful Lake Garda, which Goethe, on his visit, had called “magnificent,” trying to separate the marvelous and admirable Italian writer from his unsavory companion. I caught the afternoon bus out of town, and made it back to Torino by late the same evening.

I spent my last week wandering around gazing at everything, saying goodbye with my eyes, entering dark churches on rainy afternoons and returning to museums I had already visited. I abandoned my foolish infatuation with the intern from Sardinia. It had been a case of pareidolia after all, or a matter of witchcraft. I visited Brunilde one more time, who had been angry at me after the last lunch for refusing dessert, a strawberry delicacy which the blackboard claimed was “the cake of love.” Probably she had cursed me, and my refusal to eat the cake was the cause of my romantic failure. This time I was all alone with her in the little restaurant. We talked despite my faulty Italian and her non-existent English, and she even gave me the name of another restaurant, scribbling it on a little piece of paper, which I did not lose and used the following day. I knew better now: I would do whatever she said and eat whatever she suggested. Lunch was orecchietti with spinach pesto and a mouth-watering cutlet swamped in delicious artichoke sauce, a glass of red wine, sparkling water, and for dessert a divinely magical zabaione with roasted almonds, an espresso, the traditional shot glass of absinthe-soaked grapes, and something extra this time, to mark my initiation: a little jar of sugar cubes soaked in liquor and spices, which I did not know really how to eat or drink. She became frustrated with me and took it away, “Only the sugar, only the sugar;” but she had accepted me, just the same, this woman whose gruffness was a legend, but whose favor I had longed for. I was sure she was a witch, and that she could help me or hurt me. After the espresso, I paid the bill, but was short some 60 cents. She waved me away; it was a mere trifle between such good friends. I wished her a beautiful life, una vita bella, and Brunilde the fierce blew me a kiss! I was blessed.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

On the way to the airport, the Alps, covered in snow, were visible behind the utilitarian architecture at the edge of the city. All along the street, shutters opened and green curtains were extended from inside to out and draped over the little balconies. From a tall building, a white sheet, like a small cloud, was shaken out in the fresh morning air in the wind and sun. Church spires rose up, shopkeepers brought out boxes of fruit for display, and old men in gray caps trundled along the sidewalk, newspapers tucked in the pockets of their old tweed jackets, ready to be unfurled along with the far-off world at the nearest caffè. The time had come to leave, and the following were my last words with which I armed myself for a return to the American landscape of ironic nihilism, that nihilism born in part of a fear of the complexity inherent in material objects and in the often painful distance between dreams and reality which they reveal:

Whosoever today does not respond, does not resonate to the stirrings of beauty and the energetic life force of the world as it is, who is not filled with wonder at its teeming multifarious richness, who mocks those in the past who have made objects and symphonies and wrote poems to celebrate the intricate, elaborate, strange, cruel, and tender rhythms of life, must be dead of spirit. In the Palazzo Madama museum, after bathing in sunlight streaming into a room of baroque golden splendor from a grand window, I entered the tiny tower housing a collection of small treasures, and any lingering doubts about meaning were immediately purged from me. I knew that the doubters were blind, deaf, and dumb. These intricate treasures were immediate palpable evidence of the perennial human need to celebrate the real delights and dangers of nature and civilization. Carved ivories, etched gems, blown glass, cast bronze. Fancy— made out of the real substance of the physical world, its colors and textures and qualities. I was thus armed to do battle against the skeptical intellectuals and their social construction blasphemy. I knew: Whosoever does not love Nature and the artifacts of humankind’s love of matter (colors, curves, sounds, textures, words, flavors, rhythms, light, light, light!) may as well be dead. Such a one is bereft of heat, of senses, of love, of lust, is a lizard of theoretical idiocy; just as much a repressor of the instincts and the body and nature as any inquisition or poison-spider priest. Philistine sophisticates, parading as the new intellectuals and new anti-artists, may you chortle on the dust of your own dreary scoffing. We others, we naïve ones, have been filled with wonder by the beauty of the world.

—Genese Grill

.

Genese Grill is a writer, translator, and book artist, living in Burlington, Vermont. She is the author of The World as Metaphor in Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities (Camden House, 2012) and the translator of Robert Musil’s Thought Flights (Contra Mundum Press, 2015). She has just finished a collection of essays entitled Portals: Reflections on the Spirit in Matter, which is looking for a nice publishing house in which it might live. Essays from the collection have appeared in Numéro Cinq, The Georgia Review, and The Missouri Review, and one of them won the 2016 Jeffrey E. Smith Editor’s Prize for Nonfiction. She is proud to be on the masthead of Numéro Cinq as special correspondent.

.

.

DG intrepidly negotiating hazard.

DG intrepidly negotiating hazard.

Nietzsche ca. 1875

Nietzsche ca. 1875 Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Nietzsche dedicatory plague in Turin

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill. Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932)

Gabriele D’Annunzio Reading by Mario Nunes Vais (1856-1932) Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.

Page from An Apology for Meaning, Artists’ book by Genese Grill.