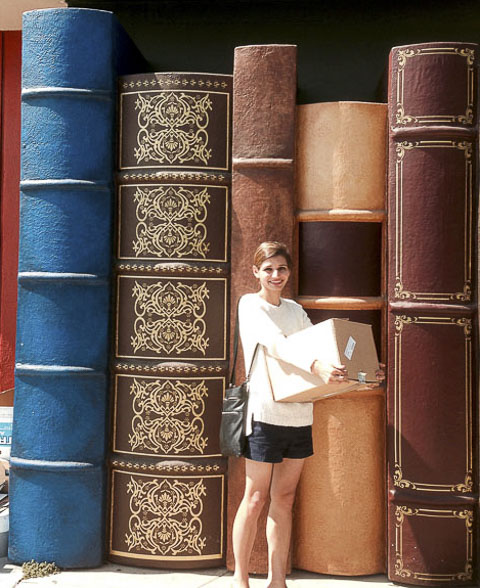

James Joyce & Sean Preston

James Joyce & Sean Preston

.

“I’d love to be able to sing, or play piano. Can you imagine how obnoxious I’d be if I had a tangible talent?” he said to her, as though a more discreet gift bubbled beneath his surface.

The pair crossed the road. He did that thing where he blocked her way with his arm, intending to lift this arm barrier when an opportunity to cross the road arose. She did that thing where she stepped through his arm barrier a second earlier than he would lift it, indicating that she did not need his help crossing the road. He didn’t mean to condescend, not that he cared if he did, but it was not his intention. He found crossing the road challenging. There were several near misses in his youth; he worried that they would die crossing the road.

She had her habits. One of them was buying cheap furniture from places that were so fucking far away, by the time you paid for travel to the ungodly zones of south-west London, you hadn’t really saved much money at all.

This habit is why the pair stood outside a house in an area of London that they had never been to before. She looked around, the air smelt unseasonably fresh, wet with Autumn. A tree that stood in the front garden had been chopped to a stump. Somewhere in her that made her feel glum. Still, it was a beautiful house, and beautiful houses encouraged something close to hope, she had found.

“Wouldn’t you like to live around here?” she asked.

“Why? So we can travel all the way to north-east London to get cheap furniture?”

“Stop moaning. Always moaning. I’m paying for it,”

“It’s not the paying for it. I’d happily pay for it and stay at home and let you carry a chair all the way home.” He said, before a satisfyingly timely sneeze shook his world. “Ugggghhh. Fucking cold; fucking eBay.”

“How long have you been ill for?”

“Dunno. Just sort of came over me today… like a…”

“Don’t do the like thing.”

“Came…. Over… Me… like…”

This habit is the habit of trying to be funny. It is a noble pursuit. Whatever simile he came up with would be irrelevant. He believed the real humour to be derived from trying to be funny was not any resulting wit, but the actual pursuit of humour itself.

*

Armchair collected, the pair emerged from the house, the chair arched on his back. She would pirouette down the garden path, thanking the woman who had sold the chair, smiling wide, complimenting the beautiful garden, saying goodbye, wishing well, assuring the seller that they were OK to carry the acquisition.

Once outside, alone, they stopped to work it all out. They hadn’t thought this far ahead. She took the front legs of the chair – a thick oak frame with the promise of reclineability, and he cupped the back legs with his hands, bearing most of the weight. It wasn’t working. It was awkward. He just wanted to do it his way, to carry it on his own. But more than that he wanted to complain.

“This is much bigger than you said it would be.”

“Well, she was standing next to it in the picture so it looked little. I didn’t expect her to be that sort of bigness.”

He laughed at that. Her lazy TV parlance threw up some excellent descriptions from time to time.

“Yeah. She was a sort of a weird bigness though. Mainly big below the waist. Like a Weeble.”

She nodded in agreement, smirking politely.

“Like Mrs Doubtfire when she messes up the costume change in that restaurant bit.”

“Or one of those children’s’ drawing where you fold the paper and draw the next compartment…”

“Yes, yes… like some kid drew it and she came to life, “ he added. “Y’know, I once broke up with a girl in infants by writing: ‘You’re dumped’ on the t-shirt of the middle torso bit.”

“You’ve told me.” A habit of his was to recall occasions in which he had outsmarted or bettered romantic interests in his life.

“I bet you used to draw a Papa Roach t-shirt or something shit like that.” He said, hurt, before dropping the chair on one side, sending the leg into his thigh.

“FUCK. Fuck, fuck, fuck. For fuck’s sake.” He put the chair down and continued the display of anguish. “It’s not working. Let me carry it on my own. You’re too low bodied.”

“You’re holding it too high.”

“If I hold it lower I’m bending my back like a fucking tramp.’

It was her time to perform now. She displayed doubt; reservation at the analogy.

He picked up the chair, hoisted it on his back. “Tramps bend.”

“Are you just thinking of Fagin? Because he’s not really a tramp.”

“Of course he is, he wears fingerless gloves.” He stepped down from the pavement to avoid an oncoming family that, to his utter dismay, had not single-filed. “Ahhh, this fucking thing. I’m not well enough for this.”

“I’ll give you a blow-job when you get home.”

“No you fucking won’t! Don’t fucking say that if it’s not true.”

She shook her head. Now it was her turn to be hurt. “I paid for it; I pay for fucking everything for the house. You never buy shit for the house.”

“You care about the house. I don’t. I don’t buy shit for the house because I don’t care. I don’t fucking go on at you for not buying porn because you don’t fucking like porn. What would be the point?”

“What porn do you buy?”

He picked the chair back up. “Blow-job porn. Men getting blow-jobs from girlfriends and not carrying chairs.”

“Not-carrying-chairs porn?”

“Welcome to 2016.”

*

The tube was fairly empty. A real reprieve, he thought. The presumption that the carriage was going to be busy had made him anxious. Seeing the lit carriage pull up with whole sections empty delivered a lightness to the evening. The worst was over. The unknown: gone. The meeting of strangers: gone. The carrying: the worst of it behind him.

She noticed his mood variations and had a basic understanding of root cause. Food was a great modifier, of course, and there were also antagonisers and pacifiers at her disposal. She used them sparingly, used them well. Right now, she pacified him by mothering him. Her hand rested gently upon his skull, her fingers stroked his crown. He couldn’t kiss in public, so it had always struck her as odd that he was so readily mothered in front of people. The carriage was emptyish but even if it had not have been, he would’ve let her cosset him.

“So illlllll.”

She smiled. Not a performing smile. “I know.”

“I’m always so sick all the time.”

“My little permanently ill poorly child.”

“Are you poisoning me?”

“To death. “

“At least I’ll get some sleep and won’t have to carry chairs home.”

Then he did that thing he does in sitting up very suddenly, remembering something important, a matter of urgency somehow recovered:

“I really wanted to watch Space Jam the other day.”

“It’s on iPlayer.”

“It’s not on iPlayer. I checked.”

“I’ve got it on VHS,” she said, regretting instantly.

“What fucking good is VHS? We don’t have a video player. I have one video and it’s porn and it’s useless because we don’t… have…. a video player. When I want to watch Space Jam, I watch it online, when I want to come, I come to stuff online.”

“So loud. Shut up.”

“Wasn’t that loud.”

Quiet, briefly.

“Always talking about coming.”

“Well. I dare say I wonder why.”

“Ooooo. So dry. Such great ‘dry comedy’.”

“That also is very good dry comedy. Much drier than mine because you really prolonged the bit where you said ‘dry comedy’. Dryer… than… a Ryvita.”

“Not great.”

“A Ry… vi… ta… with a hangover.”

“Yeah. Still not your best work.”

And then that silence where the pair go who knows where.

“Actually, I was going to say,” he said, finally, “Why did you tell Brian that I would be unlikely to want to go on any holiday with them this year.

”Well I dunno. You said you didn’t want to go away.”

“No. I didn’t want to organise going away.“

“Well I dunno-uh,” she protested again. “He mentioned it to me and I said I wasn’t sure because I knew I would be in trouble if I said the wrong thing.”

“No one is in trouble in this relationship. Least of all you.”

Silence again. The tube stopped. The doors chimed. The doors opened. A girl with an ironically garish Gucci sweatshirt got on. It was the sort of sweatshirt his girlfriend used to wear when they first started seeing each other. It was tight, promised nothing. There was charm to the train girl’s makeupless face, and the dampness to her neck, flushed red, was encouraging somehow.

He stared at the girl. He is a fool in this way. He mostly thought of how much he wanted the sweatshirt, but also, inevitably, he thought of the girl naked. He learnt to hate this in himself, or maybe she had taught him. He considered this before an awareness that his partner was staring at him staring at the train girl came over him suddenly, dreadfully.

“God. Doesn’t she… doesn’t she look like… actually you don’t know… Thingy, anyway.”

He crossed his arms, checked his shoes, contracted his lips, raised his eyebrows, aware that his subterfuge had fooled no one. But he is unyielding. He will maintain his innocence, should it be questioned. He shouldn’t have panicked, he should have said nothing, but he did. He would’ve grasped at anything.

“Oh, I sorted that problem with the toilet seat.”

“What problem?” she asked, poker faced.

“It kept moving side to side. Had to get underneath it and screw it back up,” he said, performing the actions as he explained.

“I hadn’t noticed.”

“Yeah, it moved side to side.”

“Maybe you can fix Catherine’s as well.”

There it is.

“What?”

“Maybe you can fix Catherine’s toilet as well.”

“Why this again?”

“You’re such a fucking liar.”

“What are you on about?”

She shook her head. Rueful. She was rueful. And she was a volatile human being. She approached eruption. He had seen this many times. This was their habit, and it had to play out. He hoped that she would take pity on him. It sometimes went that way. He wished that he could take back all the moaning about the chair, he wished that he could go back to being mothered, or smothered. He wished he could go back to carrying the chair. He didn’t want the Gucci sweatshirt, no matter how beautifully garish it was, or how beautifully it framed the train girl’s tits. He wished all thoughts of nakedness could be expelled forever. He just wanted her to take pity on him, see his suffering. And this time she did. Sort of. She wasn’t going to let it rest yet, but there was calm to her.

“Look at your face, you look so panicked.”

He sensed that he could speak freely. He might’ve ventured exasperation, even.

“I’m not panicking. I just hate being accused. I’m sick, I’m picking up a chair, and you just wanna turn it on me somehow so you’re the upper-hand person. You want to be in control; you hate it when I get to be fed up about something. So now you’re bringing up nonsense about some girl I fucking hate anyway. And she’s ugly. I wouldn’t have sex with her if I was single.”

“So your life is basically just not having sex with people you want to because you have a girlfriend?”

“That’s every man’s life!”

Sssh.

“What makes you think that’s not every woman’s life too?”

“Because they don’t just try to have sex all the time when they’re single.”

“Are you having sex with her?”

“For fuck’s sake, no!” And then a sneeze. A big one. Followed by a second. “I’m too ill for this shit.” He wiped his eyes, sniffed a few more times. “And too grumpy in life now to make anyone else want to have sex with me. Way too miserable a conversationalist. And deaf too. I can’t hear anything in clubs anymore. Could you imagine a chat with me at some bar? ‘Hey, y’alrght, what’s your name?’ … ‘Yamya.’ … ‘What? Never mind. What you drinking?’ ‘Yamya.’ … ‘Oh fuck off.’”

What a reward it was to hear her laugh. Better yet when she had to look away to try and hide it.

*

“Nearly home now,” she said, pointing out what was undeniable. He offered nothing, the chair on his back, the air colder, his mood subdued, beaten. “So did Brian try it on with anyone the other night?”

It was her habit to talk, to find out what had happened.

“Yes, this one girl. She was horrid.”

“What… bitchy?”

“I dunno if she was bitchy. I mean she was horrid to look at. Discouraging face.”

“Perfect for him. So what went wrong then?”

“He commented on her facial hair.”

“What the fuck? Why would anyone do that?”

He looked at her now. “I know, I know. She did have a fair bit going on though. Not that he should have said anything.”

“What did he say?”

“I dunno. Some joke about signing up to her Movember.”

“Oh my God. What an actual dickhead.”

“It wasn’t even part of his routine, he was trying to get somewhere with her. He came up to me later asking where she was gone. Said he loved her.”

“He probably did.”

He laughed. He loved it when they got on like this.

“’She takes photos, maannn.’”

He loved it when they put other people down.

“Ugh, lame.”

He loved it when they saw the same thing.

“Totally”

When they understood.

“Dweebs. The lot of ‘em.”

When he remembered why.

“Why do all girls take photos?” she complained.

“Fucking excellent question. I honestly don’t know, but I have never been out with a girl before you that didn’t consider herself a photographer. It’s like men who are DJs. ‘Yeah I DJ’d at my mate’s thing the other night.’ … ‘Cool, did your girlfriend take photos of the night oh she did oh well that’s fucking great cheers mate.’”

“I think men find it attractive because it reminds them of porn.”

“Because some porn is photos?” he said, labouring a confused expression.

“Yeah.”

He nodded, accepting the suggestion as at the very least valid.

She offered: “Photography… pornography.”

*

The armchair didn’t fit. That was obvious from the minute they were in the living room. The cove it was supposed to slot into was way too narrow. The pair stood, trying to figure out whether there was anything that could be done. But there was nothing. It simply would not fit.

He looked at her, his hands on hips. And she looked back at him. She did that thing, that exaggerated grimace.

“I love you,” she said.

“I told you,” he whimpered, immediately.

“Don’t look so satisfied. You look like your grandad that time he read that article about tofu giving you cancer.”

“Don’t. Even.”

“Do you want a blow-job?”

He sighed. Sneezed. “I love you too.”

—Sean Preston

.

East Londoner Sean Preston is the editor of short fiction platform Open Pen, considered by Francis Plug: “More like a shot of absinthe than a pint of boring lager.” Sean is an ex-pro wrestler, full-time thing-maker at a South London record label, and short fiction writer.

.

.

Agustín Fernández Mallo (Photo by Aina Lorente Solivellas)

Agustín Fernández Mallo (Photo by Aina Lorente Solivellas)

Nephin mountain

Nephin mountain  Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin

Amanda Bell and daughter near the summit of Mount Nephin Author 1971 or 1972

Author 1971 or 1972  The author at Pontoon, 1972

The author at Pontoon, 1972 Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf

Author’s grandfather and brother collecting turf The author and her brother

The author and her brother Mayo Road

Mayo Road