Rosalie Morales Kearns is a writer of Puerto Rican and Pennsylvania Dutch descent. She identifies three major childhood influences on her writing: fairy tales (unexpurgated) from all over the world; Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass; and her parents’ well-intentioned efforts to raise her a Catholic, all of which gave her a deep appreciation of, and respect for, absurdity.

That special appreciation is much in abundance in her first book, the story collection Virgins & Tricksters (Aqueous Books, 2012), which contains an ecumenical cast of spiritual characters (gods from all over the world), and a diverse collection of humans (a psychologist, a biology student, and the wives of a pirate, a revolutionary, and a priest, to name only a few), all of whom range about a wide field of history. And throughout these stories Kearns offers equal opportunity to realism and its cousin, magical realism.

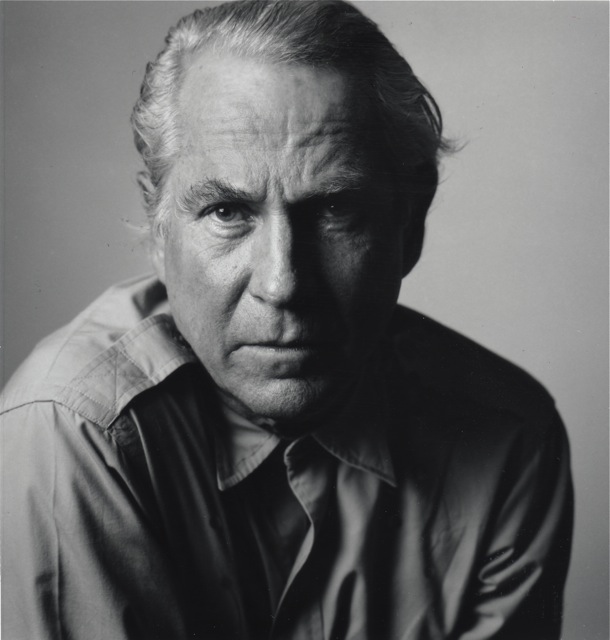

“Triptych” is the only story in Virgins and Tricksters without magic-realist elements, though it shares with the other stories a deep sympathy with misfits and a celebration of the potential for human connection. Many stories in contemporary fiction begin with a version of normal and then slowly break it to pieces; “Triptych” reverses this familiar plot pattern and instead offers the reader, brilliantly and with sweet empathy, three lonely souls who slowly find their way to each other. The writer Katherine Vaz calls this story “a little masterpiece of carefully observed lives–Larry with breathtakingly long hair emerges as one of the most memorable characters a reader can hope to find–and when divergent paths merge, the book concludes with a satisfying upsweep. Solitary beings settle inside mystery.”

—Philip Graham

Larry

Saturday midmorning Larry wakes up, enough to turn off the muted TV and worry that he’s forgetting something important, not enough to keep from falling asleep again. Hours later when the screen door opens, shuts, and he hears his daughter’s voice, it all seems part of the same long, pleasant daze. He keeps his eyes closed, can hear Molly in the kitchen. She’ll be unloading her school books, her laptop onto the table. Now she’s leaning over him.

“Dad.”

“Hey, baby.” He looks at his watch. Almost noon. He’s on afternoon shift now, and still hasn’t managed to adjust.

“You fell asleep on the couch again.”

He sits up, gives her a kiss on the forehead, lets her steer him into the kitchen.

“No offense or anything, Dad, but it’s kind of an old-man thing to do. Even Grandpa doesn’t fall asleep in front of the TV.”

Larry opens the refrigerator, considers his options.

“You want a sandwich, Moll? Eggs?”

“I ate already, I’ll just have coffee.”

Slowly he starts thinking straight, finding what he needs—spatula, frying pan, oil. As he feels more alert the nagging thought from the early morning comes back. Something he needs to remember. He almost has it.

It’s gone.

He opens the fridge again, takes out eggs, Canadian bacon, a package of shredded cheese.

“How’s your mom?” he says.

“Fine.” Molly switches the coffee maker on, takes two mugs from the dish rack.

“She says hi.”

Larry tries to picture Cynthia saying this, Cynthia at the wheel of her Mercedes. Have a nice weekend, honey. Tell Larry I said hi. He tries it different ways. Tell your dad I said hi. Say hello for me. None of them work. His imagination stalls right after Have a nice weekend.

Cynthia wishes him well. When she thinks about him.

She’s planning on taking Molly to Italy with her for a few weeks this summer. Time when, normally, Molly would be staying with Larry. But okay, he can hardly begrudge her. Italy instead of Globe Mills, Pennsylvania, population 316. Adjacent to Meiser, population about the same. And beyond that the livestock auction, open Wednesdays and Saturdays, and beyond that Route 522 will take you to Kreamer with its grain elevators to the east, and Middleburg the county seat to the west.

Molly lives with her mother and stepdad in the next county. Lewisburg’s a college town, but even that’s boring for Molly. She asks Larry sometimes, what he did at her age, and he doesn’t feel right telling her. Larry at sixteen was drinking beer, getting laid. Not taking SAT prep classes, drinking coffee at bookstores with her friends, volunteering on environmental projects to clean up the Susquehanna River. Not going to Europe.

Larry sits down at the table with his plate. “Well,” he says, “you tell your mom I said hi too.”

Molly nods, takes his fork, and picks out bites of scrambled eggs, avoiding the Canadian bacon.

He looks at her textbooks. Chemistry, pre-calculus. Another thing he wasn’t doing at her age.

“How’s it going with those?”

“Fine. I’m getting all A’s.”

Molly hands him his fork and he starts eating.

Just the other day he’d been sixteen himself. Back then he couldn’t imagine anyone more different from him than a sixteen-year-old girl, especially a smart one. Now here he is almost thirty-eight and one of them is sitting across from him at his own kitchen table.

“I never could figure out math,” he says, and the memory from the morning, the nagging thought, comes back to him now. The synapses have made their necessary connections. Perhaps his subconscious was counting up all the other things that are mysteries to him, and now he’s grabbed his keys and is rushing out the back door.

The truck.

He gets behind the wheel, pats the dashboard. “Okay, honey?” he says, and slides the key into the ignition.

The “service engine” light comes on, as bright and alarming as it looked last night.

Last night. When he’d decided, if he paid attention to her first thing in the morning, everything would be okay. No need for repairs that he couldn’t afford. And here it is noon.

“I take you in for maintenance regular as clockwork. Get your oil changed, your tires rotated.”

He pops the hood and goes round to inspect the engine, making sure to pull his hair back first. Ever since he let it grow long he’s been wary of anything that throws off sparks. He frowns, tries to convince himself he understands what he’s seeing. People expect him to know about cars, he expects himself to, isn’t sure where he was or what he was doing when other boys were learning about this stuff.

He gets back into the driver’s seat, tries to relax. He and the truck, they’ll relax together. “You’re going to change your mind,” he says. “I’m a patient man.”

He flinches, but only a little, when he hears a fist pound on the roof of the truck. The arrival of his neighbor, Dirk, is usually punctuated by loud noises: a door crashing open, stomping feet. Dirk leans down to the open window and bellows, “Got a cordless power drill I could borrow? Mine broke.”

“Sorry.”

“How about a Yankee screwdriver?”

“I don’t even know what that is.”

“Shi-ii-it. My kitchen window, hinges on the shutters’ve rusted off. If I ever buy another fixer-upper, take a two-by-four and beat me.”

Everything about Dirk, including his voice, is outsized. He’s six-four and two-forty, heavy beard and a full head of hair even though he’s over fifty. A man like this, Larry figures, has to know about car engines.

“Hey,” Dirk says, “they’re hiring at the UPS on Rt. 15. Pays more, I bet, than driving that ambulance. Plus benefits.”

“I’ll keep it in mind.” He might have to work two jobs, to get the truck fixed. “Can I ask you—”

“What’s on your face, man?”

Larry runs his hand over his cheeks, remembers the sofa and its burlap-like upholstery. “Couch pattern.”

“That’s sad.”

“Dirk, what would you do if you saw this light on your dashboard?”

“Service engine? Hell, I’d take it to a mechanic.”

“Should have checked her this morning,” he says to Molly later. “I knew there was something I had to do when I woke up.”

“How would that have made a difference? I mean, it’s not like the truck felt neglected, right? Dad. Right?”

“Okay, well. I thought maybe, if the engine, I don’t know, had a chance to rest overnight.” Or change its mind. He doesn’t say that out loud.

“That’s magical thinking,” she says. “We learned about it in social studies. Seeing connections between unrelated events. People have been doing it since prehistoric times. Like if there’s mist in the morning and you have a successful wooly mammoth hunt later on, you think the mist is the reason for it.”

Wooly mammoth—that would taste gamey. They sell bison burgers at the concession stand at Penn’s Cave and Larry hasn’t been able to bring himself to try one.

“Or if there’s a certain constellation of stars on a day when something good happens, you think it happened because of the stars.”

“How do we know it ain’t connected?”

“Dad.”

She stands behind his chair, kisses him on the top of his head. She runs her hands through his long hair, something she’s been doing since she was small. That, at least, hasn’t changed with the years.

“There’s no cause and effect relationship,” she says, slowly and carefully, “no connection between your attitude toward the truck and whether or not it has engine trouble.”

She saw the connection when she was little. If the yolk don’t break when I crack this egg, he would say, we’ll have perfect weather to go swimming down at the Middle Creek. Or If we spot the Big Dipper tonight, we’ll see a bear tomorrow when we drive over Shade Mountain. She played along enthusiastically, checking the night sky, or reminding him not to step on the cracks in the sidewalk. Cheering when the yolk didn’t break, or the engine started on the first try.

Patrice

Monday afternoons Patrice is allowed to close the fabric shop early. That way she can get to Lewisburg in time for the memoir writing class she’s taking at the YMCA. She doesn’t know what today’s assignment will be but she’s nervous about it already. She’s sure she didn’t do it right last time and the teacher seems like she’s losing patience with her.

“To explore a memory,” the teacher is saying when Patrice arrives, “it helps to start by focusing on something ordinary. Small, concrete, vivid details.”

Patrice lingers in the doorway. She doesn’t want to interrupt, and she feels shy around the others here though she’s normally outgoing. There’s a retired chemistry professor in his late sixties, but other than him Patrice, at 52, is the oldest person in the room. Also the plumpest. And from what the others have said about themselves, she knows she’s the only one there who hasn’t gone to college. One of the women is a full-time mom, another works as a personal trainer, and there’s also one who works at the college with an impressive-sounding title, dean of something or other. There’s only one other man, the owner of a café in town.

They’re clustered together along one side of a cafeteria-style table, listening to the teacher as she paces in front of them. They turn when they sense Patrice behind them, smile, make room for her. People used to do this for her in high school and on lunch break at the factory.

“We live our lives in our bodies, we touch things, we see things. It’s that ‘thing-ness’ that you want to always be aware of. Try to bring that into your writing, and it’ll lead you to more profound, interesting realizations. That’s what we want to do here, write honestly about ourselves, our lives.”

The teacher is wearing a flowing skirt and blouse, both black, with flashes of deep color, turquoise, forest green. Her bangle and bead bracelets make bright clinking sounds when she moves. She’s in her mid-forties and wears her long hair proudly undyed. The silver streaks against her dark hair look dramatic, sophisticated, unlike Patrice’s random swirls of gray, hidden somewhat with the help of Clairol’s Golden Medium Brown.

Patrice catches the teacher’s eye, but she responds with an overly bright smile that she holds up like a shield, and Patrice knows what the teacher is seeing: frumpy middle-aged woman in relaxed-fit jeans, lavender sweater. She’s probably particularly annoyed, Patrice thinks, with the appliquéd flowers at the collar. But why not wear flowers on your clothing, Patrice thinks. It’s spring.

The assignment today is to write about something they did over the weekend. “Concentrate on the sensory details,” the teacher reiterates. “What things looked like, sounded like, smelled like. Make the reader experience what you experienced.”

On Sunday Patrice had gone with some friends to a cemetery off Rt. 522, out toward McClure. Mildred and Gerri are old friends of hers from the bottling plant; they and her other former coworkers are still Patrice’s closest friends. You make connections with people you see every day for such a long time. Patrice had been there seventeen years before it closed and everyone scattered, squeezing themselves into other jobs here and there: convenience store, hair salon. Gerri got a file clerk job at the car dealership. Now that Mildred’s retired she’s thrown herself into family history. That day she was trying to track down the dates for some great-uncle. Patrice had gone along—her friends had gone with her to one museum after another over the years and never complained, no matter how bored they were. So while Mildred was taking notes, she and Gerri tromped around, looking at headstones and yelling to each other out of old habit, as if there were loud machinery they had to shout over instead of the headstones and neatly mown grass, so peaceful. One headstone in particular had interested Patrice, and she writes about it now:

“The last name, Huttner, is in big letters at the top of the stone, then beneath it on the left, John, 1918- and next to that, Blondine, 1918-. No death dates. I like to think they’re still alive, going strong at ninety-four. They bought the burial plot when they turned seventy, sat down with the funeral home director, a nice boy. They picked out the caskets and decided on a memorial service, chose a design for the headstone. I like to think they visit that stone now and then, John and Blondine, that they look at it and link hands and smile at each other, but they’re a little sad, too. So many friends, even the funeral director, have passed on in those intervening years.”

She stops writing when they run out of time, and when she reads her exercise out loud, another woman in the class says, “I think John and Blondine got divorced. John was probably unfaithful and Blondine kicked him out. They regretted it the rest of their lives, and they’re both buried somewhere else. Neither one could stand the idea of lying there alone underneath that marker.”

Patrice likes that version too, though it’s sadder than hers. The teacher gives them a strained smile and says something about Patrice’s writing being “speculative,” but then it’s time to go and she doesn’t say anything more about it, and Patrice is too embarrassed to ask. It’s clear to her she should have written about something else.

Later, since she skipped supper, she stops at the convenience store for an egg and cheese biscuit sandwich. The girl at the counter is talking to another girl who’s come in.

“I thought high school was boring,” the girl says to her friend. “I come in here every day and I feel dead from the neck up. I can’t believe this is my life.”

Patrice wonders, listening to them, whether she’d felt that way when she was nineteen or twenty, and if she hadn’t, and if she doesn’t feel that way now, is there something wrong with her?

She should write about things like that for her writing exercises, things that really happened. She could describe the sound of the girl’s voice, the dusting cloth she holds bunched in her hand, the way the glass and metal case where the hot dogs are roasting feels warm when you lean against it. The teacher likes details like that.

JulieAnne

JulieAnne feels like she’s been moving in slow motion ever since she opened the latest batch of photos. She’s only looked at the first one. It’s still in her hand, a picture of Amanda in black and white.

She has a color photo of Amanda in the same pose and right now she’s looking at the real Amanda in the same pose as in both pictures: sitting crosslegged on her bed, a mirror in one hand, mascara applicator in the other.

“So Mom and Dad said they’d try this low-carb diet with me,” Amanda says. “Isn’t that cute? And we’ve all gained, like, five pounds since we started.”

JulieAnne is only half listening. She has been in Amanda’s bedroom practically every day since they were seven years old. She knows it as well as her own: the dresser, made of some kind of quilted material glued over plywood, jammed up against the bed, the bedspread in shades of maroon with metallic gold threads running through it, the nightstand lamp with the mustard-gold shade that Amanda found at a yard sale. Amanda with her dark eyes, quick, businesslike movements of her hand as she applies eyeshadow, blush, lip gloss.

JulieAnne sees the real Amanda doing all this. She looks at the Amanda in the color photo doing the same thing. She raises her camera and looks through the lens at the real Amanda. She lowers the camera and looks at the black and white Amanda.

“I’m ready for the reality shows,” Amanda is saying. “All my life I’ve been having conversations with a girl who’s got a Minolta auto-focus stuck to her face. I know how to act natural in front of the cameras.”

JulieAnne hasn’t shown Amanda her black and white image. She knows she won’t be able to explain the difference in words. She wants to keep looking at the picture, studying the light and dark, the sharp edges and blurry shadows.

It was an accident, the black and white film. Amanda had bought it for her by mistake. People are telling her she should get a digital camera, how easy it is, how convenient, but her dad grumbles that he can’t afford a digital camera and JulieAnne doesn’t want one anyway.

She walks around Amanda’s house, looks at the rest of the pictures slowly, rationing them. When she stands in front of the real thing she pulls out a photo of it: laundry on the clothesline, pot of soup on the stove.

Color had always seemed so important. Why look at a photo of laundry if not for the bright sky behind the clothing, the contrast of a dark blue work shirt and a quilt patched with pinks and golds, and next to that a T-shirt faded to pale green? But in black and white she notices how they hang on the line, or curve and flap in a breeze, notices a splash of cloud and how much brighter it is than the clear sky around it.

She wonders if she should send some of these to her mother, or whether she’d find them boring. JulieAnne has never been good at letter writing. For years now, it’s been so much easier to send her mom photos. She tries to pick interesting images—a view of the Susquehanna River from the top of the bluffs at Shikellamy State Park, the small black bear she’d seen wandering through Mrs. Aumiller’s garden. Not the everyday stuff.

When Amanda is finally finished with her makeup they drive to Lewisburg for their after-school jobs, JulieAnne at a café and Amanda at the sporting goods store across the street. JulieAnne takes the photos with her. When things are slow she looks at the black-and-whites she’s taken here, shots of the customers, the cappuccino machine, the pastries in the lighted glass case.

The light is what fascinates her. It flashes off the ceramic mugs and varnished wooden tables like a live thing, like it should be dazzling the people sitting there sipping coffee, reaching for sugar. Instead they talk to each other or stare into nowhere; they look like they’re from a foreign country, another century. They seem kind. They’re used to shimmering light. That’s how their world is.

.

Larry

Tuesday afternoon is a slow day at work. They have only a few calls. A sprained ankle at the mall. A little later a possible concussion over at the high school soccer field. Mostly Larry plays cards in the dispatcher’s office with Kevin.

He asks Kevin about the truck, what the problem could be, how much it might cost.

Kevin says he doesn’t know. This is his response to almost everything Larry says.

Larry can’t decide whether to apply for the UPS driver job. He’s not sure how good he would be at it. If no one’s there to accept delivery you have to decide whether to leave a package, whether there’s enough overhang over the front door to protect it from rain, or go around to the side and risk running straight into an angry dog. Or you open the door to a screened-in porch and a jumpy homeowner opens fire on you. It’s harder than it looks.

He tries to hold onto a job as long as possible, no matter how bad it is, because he hates job interviews. They always ask you about the meaning and direction of your life. Where do you see yourself in five years? in ten years? and he can tell they’re asking because they’ve seen the questions in some management textbook. They don’t care how you respond. It’s just, they’re the boss and you’re a worker and that gives them the power to ask you a personal question and sit back and watch you squirm while you try to think up an answer that’ll sound good. Just once he would like to be able to be honest about those questions.

So, Larry, why did you leave your last job?

I didn’t actually leave. I’m a nice person, and I try, but I’m kind of scatterbrained.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

Well, in five years Molly will be 21, and finishing college, that’s how I figure time, ever since she was born. She’ll probably keep on with her schooling, become a professor or a rocket scientist or something. And I’ll be 43 and that’s a pretty good age, I think. It’s not the age when men have a midlife crisis, but that’s relative, isn’t it, midlife. And Molly’s mother will be 43, and still married, and still beautiful and we won’t have any reason to say anything to each other until Molly graduates from whatever, and then I guess there’ll be a wedding at some point, maybe baptisms and such. Oh, I guess you’re asking me about my job, what kind of work I see myself doing. Let’s see, I drive an ambulance now, so I guess the next step is EMT and then after that nurse, and then doctor. So yeah, I guess in five years I’d like to be a surgeon.

In the early evening a call comes in for an elderly woman with chest pains. They pick her up at one of those huge new houses over at what used to be Middleswarth Dairy Farm. Enormous picture windows, cathedral ceilings, heating bills alone that must be more than Larry’s rent. Cynthia has a house like that.

The place is in an uproar, everyone talking at once—the woman with the chest pains, her daughter, son-in-law, grandkids, dogs. The daughter’s yelling, she wants to go with her in the ambulance and the mother’s saying no, she wants to go alone, leave her in peace.

As soon as Larry backs out of the driveway, she says she feels better.

“We’ll just check your vital signs, ma’am,” Kevin says. He’s sitting in the back with her. “And we’ll have—”

“—Call me Virginia. It makes me feel like a fossil to be called ‘ma’am.'”

“Okay, uh, we’ll have the doctors look you over to be sure nothing’s going on.”

“I always feel better after I get out of my daughter’s house.”

“Virginia?” Larry says.

“Yes, young man?”

“Maybe it was a panic attack.”

In the rearview mirror he can see Kevin give him a look to remind him that he, Kevin, is an EMT and Larry is merely a driver and should keep his opinions to himself. Kevin had been a driver too, until he took the EMT training.

“Considering the patient is eighty-one,” Kevin says coldly, as if “the patient” can’t hear, “we’d better let the doctors decide.”

“I’m not too old to have anxiety, you know.”

Larry sees a slight movement by the side of the road. There’s no time to respond. A doe shoots out in front of them. Larry brakes, swerves hard to the right to miss her.

They careen onto the shoulder as the front tire hits something sharp and makes a loud hissing noise. They bump to a gentle stop.

“Jesus God,” Kevin says.

“I’m all right,” Virginia says. “Don’t have a heart attack on me.”

Kevin is out the back door of the ambulance and into the passenger seat next to Larry, sweeping his hands under the seat.

“Where are the goddamned flares?”

“Can we watch our language here?” Larry says.

“I would, but I don’t know a polite word for fuck-up.”

Larry and Virginia sit at the open back of the ambulance, legs dangling out, while Kevin rushes around setting flares and talking to dispatch. “Right,” he says into the cell phone. “Keep the patient calm.” He gives Larry another meaningful look.

“Well,” Larry says slowly, “I guess we should put things into perspective.”

“That’s an excellent idea.”

All kinds of ways it could be worse. One alternative is the ambulance flipping upside-down, spilling its contents of driver, EMT, and old lady all over the road, probably a dead deer somewhere in the picture too. And him fired. That could happen even without any injured humans or deer. For puncturing the tire with a patient on board. For being someone the supervisor doesn’t like.

He starts to tell that to Virginia, but changes his mind. She could be really stressed right now; she could get overexcited and her old, fragile heart would flutter to a stop.

“Why don’t I go first?” she says. “It’s a beautiful summer evening, and we’re sitting here on a country road surrounded by these lovely old oaks and maples and hickories. Your turn.”

“Okay. It’s almost the end of my shift.”

He decides there’s nothing quite like the sound of an old-lady laugh, dry and delicate. Impossible not to laugh yourself when you hear it.

“And do you always puncture a tire at quitting time?”

“Only every so often.”

“He also dents the fender,” Kevin says. “Leaves the windows down in the rain. Runs out of gas.”

That last isn’t quite true, but before he can argue, Virginia turns to Larry as if Kevin weren’t even there.

“I can’t help but notice,” she says, “you’ve got your hair tucked into the back of your shirt. Is it very long?”

“Yeah, pretty long.”

“You don’t see that so much these days. How interesting.”

He pulls his ponytail out and undoes it, without waiting for her to ask.

“Young man. My goodness.”

Some women love his hair, can’t wait to get their hands on it. It’s long, down to his waist almost, as thick and healthy-looking as when he was eighteen. His buddies hate him for it, the ones his age are already starting to thin out on top.

“It’s kind of a pain, takes forever to dry,” he starts to say, but she’s already reaching out, asking if she can touch.

“Go ahead.”

The old-lady tremor in her hands isn’t so noticeable while she runs her fingers through his hair. In fact she’s surprisingly strong.

Behind Virginia’s back, Kevin gives him a disgusted look. Larry grins. It feels good. He always likes to have his hair stroked.

“How daring,” she says, “to let it grow this long. When I was young it was considered quite bold. And getting a tattoo, that was the other thing no one did. Now all the young people get them.”

“Well that’s a funny story,” he says.

Suddenly he doesn’t have the heart to tell it. Back when he was with Cynthia she wouldn’t let him get a tattoo, said it was something only white trash did. Then when she dumped him, he went to a tattoo artist, feeling somehow he was declaring independence, he was starting over as his own self. Turned out he couldn’t decide what kind of tattoo to get.

Later his supervisor, Richard, asks him what he’s learned from “this incident.” Larry is thinking about tattoos, which pattern to get if he ever gets around to it. Maybe a leaping deer, or the letters MT for Magical Thinking. Also he’s feeling sleepy, which always happens when someone’s been stroking his hair. He makes a stab at answering Richard.

“You’re never too old for a panic attack?”

Richard looks tired. He likes “teachable moments.” He’s that kind of supervisor.

Larry tries again. “I shouldn’t swerve to avoid a deer?”

“Try to pay more attention when you’re behind the wheel,” Richard says. “That’s all. Just try.”

All told, the day went well, Larry decides as he heads for the parking lot. It could have gone badly, very badly, but it didn’t. He turns the key in the ignition, feels a surge of optimism.

The “service engine” light flashes on.

.

Patrice

It’s a slow morning in the fabric shop. An older couple comes in needing yarn. The husband took up knitting when he retired, jokes that it’s an excuse to socialize with his wife’s lady friends, but Patrice can see the artistry in his work, sweaters in intricate patterns of soft silvery grays, muted browns, grayish blues. She wonders what things would have been like if he’d been given art classes when he was young.

Margaret comes in, the owner of the bookstore around the corner. She’s a Civil War reenactor and needs blue wool cloth for a new uniform jacket.

People expect Patrice to know all about knitting and sewing. She kind of expects it herself, that somehow she would have absorbed this knowledge just by being female and living in Union County for five decades. When she first started working here, if customers had questions they would go to her rather than Tanya, her young coworker. Patrice would smile a lot, exude helpfulness. The regular customers soon caught on. Between them and Tanya and old issues of Fabric Trends and Quilter’s Newsletter, Patrice has learned all kinds of things. She knows exactly what weight and weave Margaret needs for her Union Army uniform, but she can’t resist pointing to another flannel nearby. “This plum color goes so much better with your complexion,” which makes Margaret laugh so hard she’s almost in tears.

“Nobody fought in plum,” she manages to say finally. She’s still chuckling over it later when she leaves the shop.

Patrice pictures a battlefield, infantrymen showing up in bright yellows and oranges, in polka dots, in macramé and feathers. They would cancel the war, naturally.

She writes up an order for rug-making kits, restocks the knitting needles. Tanya is straightening up quilt patterns on the sale table, and since no customers have come in, Patrice takes the opportunity to pull the hymnal out from beneath the counter and bring it over to her. She opens the book and sets it on a stack of embroidery kits.

“Tanya, honey, can you try this one?”

“Now what?” Tanya says, but she smiles. She reads the hymn through quietly, Patrice looking over her shoulder.

“It has a nice limited range,” Patrice says. “I can sing most of it except for the high notes here, and here.”

“Don’t—”

“I won’t, don’t worry.”

Tanya starts singing softly.

“What wondrous love is this, O my soul, O my soul…”

Patrice has to close her eyes to imagine the way it would sound if a hundred people were singing it, and if those voices weren’t being absorbed by piles and bolts of fabric but were bouncing off a polished wooden floor and stained glass windows on a Sunday morning.

Being Unitarian Universalists, of course, they’ve changed the lyrics: there’s no reference to God at all, let alone his righteous frown, or cursed souls, or death. The UU version has blissful hearts, friends gathered round.

She knows that Tanya doesn’t much care for church music; most girls her age don’t, but she sang in her high school choir and she can sight read music.

“Thanks, hon.”

“Where are you going to put it?”

“I’m thinking of using it for the ‘greeting your neighbor’ part. That’s the part where everyone says hello, you introduce yourself if you haven’t met the person before. Only instead of speaking, everyone would just be shaking hands while we’re singing this.” Patrice still isn’t sure about this particular song. Beautiful as it is, she’s worried that it sounds melancholy.

Patrice is trying to imagine a church service that’s conducted entirely in song. She’s been giving it a lot of thought and outlining alternatives in her notebook. She hasn’t brought it up with her minister, but as she’s told Tanya, that’s the joy of being a Unitarian Universalist. Ministers there try pretty much everything.

The chimes ring as the mail carrier leans in and waves at them and puts the mail on the counter. Patrice bought those chimes herself and put them up, thin pieces of white quartz crystal that clink against each other with every movement of the door. They make Patrice think of the factory where she worked all those years, a bottling company that did specialty soft drinks like sarsaparilla that only gourmet stores and such wanted anymore. The workers were gentle with the bottles, but there was always something that set them to vibrating, rounding a curve on the assembly line or when they were hoisted in their wooden crates onto hand trucks, and bottle touching bottle made sounds like small glass voices. She likes having an echo of that old life in this new one.

JulieAnne

JulieAnne is in her bedroom, door closed, but it’s a flimsy door—the whole place is poorly constructed—and she can clearly hear her father on the phone shouting, something he hardly ever does.

She’s trying to distract herself by looking through a book of black and white photos, a pictorial history of Union and Snyder Counties that Tracy, her stepmother, gave her. You’re not going to cry, she tells herself, ignoring the tears she’s already wiping away. She wants to climb into this book, into the black and white world of fifty years ago, a hundred years ago. Color is for high drama. Yelling. Slamming doors. Black and white is quiet, undemanding. Over and done with.

“After twelve fucking years.”

Another thing her father hardly ever does: swear.

Not that people didn’t yell and slam doors back then, she’s sure, but you can see that people in this book stopped what they were doing to look at the camera. For a minute they let go of whatever momentary thing was bothering them—bills, injuries, ex-wives. As if they knew that someone would look at this picture long after they were dead.

“You think she’s a dog, she’ll just come when you call?”

JulieAnne’s mother, Kath, has asked her to visit her out in California. She can afford the airfare now, she told JulieAnne on the phone this evening. She’s got a guest bedroom in the place she’s staying.

JulieAnne looks at the framed photo of her mother on the dresser. She vaguely remembers her as enormous, probably because she wasn’t quite four when Kath took off, minutes ahead of the county sheriff, who swept in just hours before the federal agents arrived. Still she imagines her mother as towering over her father, a short, morose man, permanently stooped as if no matter what, he’s always ready to lean over a car engine and start taking it apart.

In her vague memory, her mother is not only large but also soft and warm, with long brown hair. In the photo Kath’s hair is now short and graying, and she’s wiry and fit, kneeling in front of a kayak by a mountain river.

I’m getting my act together, her letters would often say, when the letters started arriving after five years. I want to come see you honey, and then no word for months at a time.

Her father is still shouting, but not as loud. He’s running out of steam.

“Should’ve called the DEA when I had the chance, you hippie freak.” And then: “Leave my family out of it. Moonshine’s a different story. If pot were legal you’da had no interest in growing it.”

By the time she started getting in touch with JulieAnne, Kath was living on the West Coast, running a mail order business of hemp products and healing crystals. Soon she had a website (Harness the Healing Power of the Earth). Now she seems to be running a wilderness survival program. “Rich people pay good money for this,” she told JulieAnne. “It’s all those Survivor shows. People want to have that experience themselves.”

“Don’t talk to me about no statute of limitations. Is there a statute of limitations on abandoning your child?”

JulieAnne considers sending Kath a photo of Neil, so she has an image of something other than the angry man who’s shouting at her long-distance. JulieAnne’s favorite is one where her father has a big grin; he’s listening to Amanda reading the headlines from Weekly World News. “‘Moon to Explode in Six Months,’ Mr. K, what do you think of that?” “It could happen.” “What about ‘Hikers Find 20-Foot-Tall Gingerbread House’?” “You never know.”

Amanda moved in next door nine years ago, when she and JulieAnne were seven. She was there when Kath started sending letters. By then she was fiercely protective of JulieAnne. There she’d be, ten years old, eleven, sitting at the kitchen table with Neil, each one outdoing the other in indignation. Who does she think she is? What kind of mother would leave a kid like JulieAnne? They’ve bonded over their outrage at Kath.

Her father has hung up the phone. Now she hears him, almost shouting at her stepmother.

“Why now all of a sudden? Is she between boyfriends?”

“Neil, you hush this very second.”

JulieAnne realizes she has something much more immediate and practical to consider than abstract things like whether Neil will let her go, how she’ll feel, whether to be angry, what to say.

Her mother has no photograph of JulieAnne. Not a real photograph. Or rather, she has photographs of real people, but they’re not JulieAnne.

She doesn’t think of it as lying, precisely. It began as an accident. When her mother started writing to her she’d asked for a photograph, and JulieAnne wanted to send her one of a pretty, happy little girl. Her father and stepmother didn’t take many photos, and in the ones of JulieAnne she was usually in the picture by accident. She showed up in the margins, blurred, part of her face cut off by the edge of the picture, or else looking startled, called in from someplace else to pose for a family shot without having any time to comb her hair or arrange her face with the right expression, so that a faraway mother she’d never seen could look at it and admire the image of an intelligent, interesting child.

Back then Amanda looked kind of like her, except with shorter, more reddish hair, and her face a bit plumper. JulieAnne ended up sending her mother a picture of Amanda that Amanda’s mom had taken, curled up in her bed grinning up at the camera through a crowd of pillows and stuffed animals. It was close enough.

She knew that after that, her mother would expect more pictures. For her tenth birthday she asked her father for a camera and he got her one, to her surprise, that was sleek and silvery and easy to use. She started photographing her friends: Amanda on the swingset at the height of an arc, hair flying, face upturned; or Tiffany turned three-quarters away from the camera. They were prettier than JulieAnne anyway, and more photogenic, and the little differences would be easy to explain: her hair grew fast, or she had just cut her hair, or had tried a henna shampoo for highlights, or had gained a little weight recently, or lost it, and yes, wasn’t she getting tall fast? Her mother never pinned her down with pointblank questions, but every once in a while in her letters she would mention in an offhand way, “You know, honey, somehow you look different in every photo.”

JulieAnne has tried to put off sending her a recent shot. In the last couple of years Amanda has gained a lot of weight. Anyone else would get teased and called a fat girl. Not Amanda. She takes over a room when she walks in. Her low-pitched musical voice is loud and unapologetic. She’s a force of nature, too overwhelming a presence to be a fat girl. Meanwhile Tiffany has stayed as skinny as they all were when they were eleven. Even at odd angles, the two of them look too dramatically different from each other. JulieAnne could claim to have drastic fluctuations in her weight, but that would make Kath worry for no reason.

You have to be grown-up about this, she tells herself.

She has to tell Amanda and Tiffany what she’s done. She has to get a real photo of herself to send to her mother.

She looks in the mirror, tries to picture herself in black and white.

.

Larry

On his free afternoon Larry stops at Cynthia’s house. Hank, her husband, answers the door. His hair has been getting shorter over the years. It’s almost a crewcut now; it makes his receding hairline harder to notice. He’s a tall guy with a puffed-out chest like a gym teacher, a guy who’s used to giving orders. He’s bigger and stronger than Larry. If he tried to punch him Larry’s only advantage would be his quickness. He could sway and dodge out of the way of those stone fists and succeed only in looking ridiculous in front of Cynthia.

“Hi, Larry,” he says with a tired voice and carefully prepared smile. He goes back in, and Cynthia comes out with the same smile as Hank. She’s wearing a beige tank top and blue jeans, more like a college student than the VP of a bank.

“I…” He never knows how to start when he talks to Cynthia. “Molly says you’ve got all these plans for the summer.”

“I told her to let you know. She’s going to Italy with me for two weeks in July. In August she’s taking an intensive SAT prep course, Monday through Thursday all day for three weeks.”

“I won’t hardly see her.”

“Larry. This is important. If she’s going to do early decision at Harvard she needs to take the September SATs.”

“Harvard. That’s over in…”

“Boston.”

She steps out onto the flagstone-paved front patio. There’s a teak bench next to a stone planter, but she sits down on the step that leads down to the sidewalk. She motions for him to sit next to her.

“It’s not like you’ll never see her. You’ll have her on weekends, just like you do during the school year.”

He looks at Cynthia’s bare feet, the graceful arches and polished toenails. He can hear Hank’s lawn mower out back, coming closer, fading, coming closer. The two of them were doing yard work together after supper. Hank mowing, Cynthia probably planting some annuals.

Hank has a job Larry doesn’t understand, something to do with finance. He likes to give everyone, including Larry, a hearty handshake and a clap on the shoulder. No reason we can’t be friends, he’d told Larry right off. They’d even invited him to their wedding. And the weird thing about it is, Hank could be sincere. Larry has been watching him for years, waiting for some sign of hypocrisy.

Hank likes to give brief motivational speeches. He’s given Larry one every time Larry gets fired. He even gave a speech at his wedding, to some men Larry presumed were other businessmen: something along the lines of, When I get married, it’s for life. I’m in this for the long haul and so on. You don’t walk away if there’s a problem, you make it work out.

Larry still wonders how Hank would solve the “problem” if Cynthia sat him down one day and calmly, politely wrote him out of her life. You’re a nice guy. You’re a good person. But I don’t love you. The way Larry sees it, you have no choice but to walk away from a problem like that. But not before you beg and plead and cry. At which point you stagger away, or crawl. There’s no question of actually walking.

He tries to picture giving Hank a motivational speech after Cynthia dumps him. What’s more probable is him, Larry, comforting Cynthia a decent interval after Hank’s funeral. He’s a hard-driving man; guys like that get cardiac problems.

“How far away is Boston?”

“From here? About twelve hours by car.”

“Do you know how old my truck is? It’ll never make it.”

“Larry, maybe we could talk this over by phone.”

“What’s the matter with the colleges we have here? They’re expensive enough.”

“What kind of message would I be sending her if I don’t expect her to try for the best? Think what that would do to her self-esteem.”

Hank comes around the front of the house with a pair of hedge clippers. He starts working on a yew near the bay window, and says to Larry in his jokey voice, “She’s hired me as gardener. Keeps me out of trouble.”

One of Larry’s best jobs was working with a groundskeeping crew at the golf course. Things got complicated only after the Canada geese showed up. They wandered around in packs, left droppings everywhere. More geese arrived every day. Management wanted to get rid of the geese, didn’t care how—shoot them, poison them. Larry refused. It felt wrong to kill them, and what’s more, there wasn’t any logic to it. They had to live somewhere. “We should try to understand them,” he’d said. He meant they should try to figure out what the geese liked about the golf course, how the grounds crew could change that, or find a place the geese liked better. But they laughed before he could explain. “Great idea,” a supervisor said. “How do you say ‘Take me to your leader?’ in goose? How do you say, ‘We come in peace’?”

This was the same supervisor who’d told him another time, “You’re damn close to the border of mental defective, Larry. You’re barely on this side of the line.” Larry doesn’t even remember what he did to provoke that. “You ain’t stupid, son,” his dad tells him sometimes. “You just don’t pay attention.” They’ll be sitting in the living room and his mom will go stand behind Larry’s chair and drape her arms around his shoulders, kiss him on the top of the head. “He’s easily distracted, is all.”

All of which makes him forget what he wanted to say to Cynthia, and he doesn’t think about it until he’s in his truck.

Larry: This don’t have nothing to do with Molly’s self-confidence. Your family’s richer than God. She knows she can have the best of whatever she wants.

Cynthia: What are you going to do, Larry, guilt her out so she doesn’t leave?

The real Cynthia wouldn’t put it that way. This is all he can come up with.

Larry: I’m not going to guilt her out. She shouldn’t stay around here if she doesn’t want to.

She should see the world. Italy, Boston. Cynthia, as always, is right.

,

Patrice

That evening, the exercise for the memoirs class is to write about yourself in the third person.

“Patrice loves museums,” she writes, and it makes her want to chuckle to write about herself as if she were someone else. “Especially the furniture part. Not that she doesn’t like paintings, she does, but what she loves are the ‘period rooms’ with the authentic furniture that real people used in earlier times.” Patrice knows she’s supposed to focus on concrete details. “For instance,” she writes, “a parlor, with dark hardwood floors and plaster walls painted a warm rose color, and the ornate trim around doors and windows painted in a gleaming white for contrast. The mantelpiece is made of white marble. On it are fresh flowers in a crystal vase changed every day (the flowers, not the vase). There are floor-to-ceiling windows with gauzy white curtains that I, that she could pull aside every morning to enjoy the view of the gardens.

“Patrice dreams that she lives in a museum like this. She is allowed past the velvet rope keeping people out of the rooms. She can relax in the wingchair upholstered in maroon silk, or sit at a desk and write thank-you notes on linen stationery. She gets a little annoyed at the endless stream of visitors during museum hours, but she’s grateful for all the cleaning done by the custodial staff. And at night when everyone is gone the people in the paintings climb down from their canvasses, and stretch and smile, and serve her pastry and give her foot rubs. Sometimes she agrees to change places with them, and will climb into a painting and stand in the background, and then the next day they all watch to see whether any of the visitors notice. She feels most comfortable in the medieval paintings, the ones done in oil on wooden panels. The women are solid and sensible-looking, like she is, and she feels much more at home with them than with the skinny ballerinas, although she notices that some of the nudes are large and fleshy like her, and she wonders when she’ll have the nerve to show up in one of those paintings.”

The teacher obviously disapproves, but all she says, with that tight little smile, is, “Try and remember, everyone, this is a memoir-writing class, not fiction. We write about our real lives.”

“Patrice is confused,” Patrice writes in her notebook. If she wrote fiction she would give all the nice characters a happy ending, and every overweight woman would have delicate wrists and ankles and have artists begging to paint her portrait.

JulieAnne

The guidance counselor looks exhausted with boredom, as usual, and JulieAnne doesn’t blame him. She can never think of anything to say in these meetings. What do you want to do after high school? What are your interests? She shrugs, manages an occasional “I don’t know.” Now he’s telling her he doesn’t think she should sign up for Honors English next year; she’s been making only average grades with the non-honors track, and she wouldn’t want her grades to get any lower, would she? No, she wouldn’t.

She’s also thought about learning Italian. It sounds so musical. She doesn’t mention that.

He’s filling out her class registration form. “You’re doing well with your word processing and your business math,” he says. “That’s what they’ll want to see on your record. If you decide to go ahead and get that associate’s degree.”

“I like to take pictures,” she says, surprising herself. The counselor looks surprised too. His eyes just brush the surface of her and then flicker away. Like my camera, she thinks. But no, that’s unfair. She reaches for it where it rests against her, hanging from its vinyl strap around her neck. Her camera sees much more.

As she leaves the building she shows Mr. Giacinto, the maintenance man, the photo of the west corridor, afternoon sun shining through the large window at the end, lockers shut, floor gleaming.

“Look how clean it is,” he says. “No students around, that’s why. Ha! No offense, kid.”

She wants to take a picture of the same place but with him in it, with his mop and cleaning station. He lets her talk him into it though he complains a lot and she can’t make him understand that the picture is more true with him there, if that makes sense. That the mop and the angle of his stooping body make it perfect.

By the time JulieAnne gets home there’s a family meeting going on in the kitchen: her father, her stepmother, Amanda. They acknowledge JulieAnne, go back to talking among themselves.

JulieAnne leans in the doorway, watching them.

I’ve handled this all wrong, Kath said to her last night on the phone. Neil’s so sensitive, he’s like a walking bruise.

No one has ever used the word “sensitive” to describe her father.

“So her mother wants to see her,” Amanda says. “It’s about friggin’ time.”

“Too damn late, is what it is.”

“I’m not defending her, Mr. K.”

The three of them sip their coffee. Amanda is the only sixteen-year-old JulieAnne knows who likes Maxwell House instant, with hazelnut nondairy creamer, the drink of choice in Neil and Tracy’s kitchen.

Her father lights a cigarette, takes a few drags, then passes it down to Tracy, who takes one puff and then stubs it out. They’ve been doing this for six years now, it’s their attempt at quitting smoking. One of these days Amanda will grab the cigarette and puff on it and they’ll let her do it; she’ll be completely one of them.

“It’ll happen sooner or later,” Tracy says gently but firmly. “She’ll want to meet her mother, it’s only natural.”

Amanda breathes a long, drawn-out sigh, then a prolonged hmm, meaning she has pondered this, she concedes that Tracy has a point.

Neil looks down at his coffee. The three women have learned to interpret his silences. They lean in, listen to it, breathe it in. This one feels, if not relaxed, at least not too tense.

“She talks about my family being hillbillies,” he says after a while, “like her family ain’t every bit the same. Don’t give me none of that peace, love, and understanding crap.

“Mr. K,” Amanda says, delighted, “that’s Elvis Costello.”

,

Larry

One night Larry goes out on a date, sort of. A nurse at the Selinsgrove clinic has invited him for coffee at a place in Lewisburg. There’s a poetry reading going on that evening at the café, and Larry’s afraid he’ll be bored and confused, but it turns out people are reciting poems they like, real poems from books, not stuff they’ve written themselves. The only rule is you have to recite from memory, not read. People are standing up who didn’t plan to, they get brave and say stuff they memorized years ago and never forgot. “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” stuff from Alice in Wonderland. Everyone’s laughing and clapping. Yelling lines when a reciter hesitates. And then other people have prepared. They say stuff by Robert Frost or poets Larry’s never heard of, but good ones. He wonders if it’s easier to understand when you listen to someone saying it than when you read it quietly to yourself.

The nurse runs into an ex-boyfriend at the café and ends up going home with him. She apologizes to Larry, gives him a kiss on the cheek. Larry understands. He wonders whether Cynthia would be tempted, if she ran into him after not seeing him for a long time. She’s never had a chance to miss him. Maybe that’s the problem.

When Cynthia broke up with him he showed up at his parents’ house with a few cardboard boxes. He managed to get himself to work and back, but otherwise he stayed in his old bedroom, now the sewing room. He showered only when his mom reminded him, stopped shaving, stopped getting haircuts, even though his mom offered to cut his hair herself. What he mostly remembers from that time is long fits of weeping, staring into space.

The hair started growing. He’d kept it short all his life, but soon it hung down past his ears, grew down his neck, grazed his shoulders. He didn’t notice it except to sweep it back out of his eyes, but his mom started commenting on it. She’d convince him to let her wash it in the bathroom sink, and it felt good to close his eyes and feel the warm water and her strong fingers working the suds around. The shampoo was girly-smelling but he didn’t want to offend her by saying so. “You were born with an adorable head of hair,” she told him. “But first your dad and then you, kept it short ever since.”

Molly was twenty months old at the time of the breakup. Cynthia’s parents brought her over every weekend. At first the sight of her made him cry more. He was supposed to see his baby girl every day of her life, not just on visits.

“Honey,” his mom said, “You can grieve over her the rest of the week. Sunday through Thursday, cry all you like. But are you still going to cry when she’s right there in front of you?”

“Mom, you’ve never had this. You don’t know what it’s like to be a divorced parent.”

“You were never married.”

“You know what I mean.”

“I know what you mean, and you were never married.”

He started to understand what everyone else had figured out from the start. Most likely his buddies and relatives had been making side bets over how long it would be until Cynthia threw him out.

He lay on the couch, watching his parents play with Molly on the living room rug. They’d bought her some little dinosaurs and there was this set of dominoes they had that she liked, and the three of them would make the dinosaurs talk to each other and move around and build caves out of the dominoes. Then there was this complicated situation where the dominos were standing up in a line and the dinosaurs pushed them over so that the toppled dominos formed a road that one group of dinosaurs needed to travel to another group. Why the dominos had to be stood up in the first place, Larry didn’t understand.

Molly would scamper over to the couch sometimes, gently take hold of a strand of his long hair. “Daddy pretty,” she would say.

“Molly pretty.”

He picked himself up, started walking upright, showering regularly. He started shaving again, but he never did cut that hair.

Molly continued to be impressed. “Look, Dad, your hair’s almost as long as my Barbie dolls.”

“Let’s call this one Larry.”

“That’s a boy’s name!”

“You know how your mom gets mad at me if I bring you home late? This is what she’s gonna do to me next time.” He picked up Larry and swung it around by its hair, its rigid plastic smile the only thing they could see as it whirled around faster and faster. Molly laughed so hard she started hiccupping.

People saw that hair and made all kinds of decisions about him. He was gay. He took drugs. He was a hippie. And here and there a woman who loved it. He couldn’t tell what Cynthia thought of it, though once when he’d dropped Molly off after a weekend visit, it was late and Cynthia had had some wine. She backed him up against the wall, pressed up close to him. “I’m confused,” Larry had said, and she’d laughed and shaken her head as if she’d come to her senses just that moment.

Confused was not sexy. Women didn’t want confused.

.

Patrice

The writing assignment is something the teacher calls an “inventory of the self.”

“Interpret it however you want, but try for rich description, close attention to detail. I want you to dig deep, write honestly and fearlessly. Remember, you don’t have to read it out loud if you don’t want to.”

Patrice begins to write. “On Nittany Mountain the rain seeps through crevices in the ground, drips through limestone and lands in Penn’s Cave. You take a boat through it, riding on all that accumulated rain. It carries your boat out through a little opening so you have to duck down, and then you shoot out into the open. It’s the beginning of Penns Creek that goes on for miles until it empties into the Susquehanna, but there at the cave opening, it looks like a pond. There are swans, beautiful and bad-tempered; they blare at you or ignore you with elegant scorn. Then you get out of the boat and go through the animal preserve. Elk, bison, white-tailed deer. Some of the deer are albino or recessive or something—all white. If you came across one of those alone in a forest you’d think you’d seen a ghost. Wolves, timber and gray, they point out which is the alpha male and the alpha female as if you couldn’t tell just by looking. And the black bears. One of them is a black-bear version of albino, they call him a cinnamon bear and that’s exactly the color of his fur. They tumble all over each other; they like people but you wouldn’t want them playing with you. They could snap your neck without even meaning to—oops, the toy’s not moving anymore. And then a mountain lion, just one can bring down a deer, where it takes a whole pack of wolves to do the same thing, and she comes right over to the chain link fence and you’re inches from those cool feline eyes looking into yours”—and time is up.

“Yes, but this is an inventory of the self,” the teacher says. “Where is the self in this piece?”

At first Patrice’s instinct is to back down, apologize, but she’s tired of backing down.

“The self is what’s looking at the animals,” she says. Polite but firm.

I’ve been on this planet longer than you, she thinks. That should count for something.

The teacher looks stunned. “We writers,” she says after a pause, “we’re artists, you know, we takes things in all different directions. That’s something I’m learning from you, Patrice.”

Sometimes, Patrice realizes, all it takes to stop a bully is to tell them they’re being a bully.

After class she meets three of her friends at the mall. Mildred needs something at the Dress Barn and Ruth and Gerri want to look at baking dishes at Boscov’s, and then they follow Patrice to the bookstore, their last stop. They’re tired by now. Mildred, Ruth, and Gerri settle heavily into armchairs near the religion section, where Patrice looks for the next title they’ve decided on for the book discussion group at church, something by the Dalai Lama. Gerri scans the titles she can see from where she’s sitting.

“When God Was a Woman. What’s with the was? Heck, she still is.”

“The title should be, God Is a Woman.”

“With gray hair.”

“And blisters on her feet.”

“And cellulite.”

The cellulite part makes them laugh. Patrice didn’t even know the word when she was growing up, none of them did. They still don’t care.

Later Patrice smiles at the memory, Gerri’s laugh like a loud hoot that she’s never self-conscious about, no matter how many people stare. Mildred does a kind of hee hee hee, a devilish cackle that makes the rest of them laugh more.

They can’t sing any better than Patrice. They’ve threatened to come to the UU church the day of her musical service “and join in the heehawing,” as Ruth put it.

It’s after nine when she gets home. She turns on the armchair lamp in the living room, then the kitchen lights and the little TV she keeps on the counter. No husband there to welcome her, never has been one. Then again, no husband to demand to know where she was, no husband to ignore her or criticize her for getting fat. Her friends have the whole range of husbands, and they leave them at home in the evenings, eat out together after work, and then go shopping or to a movie.

Patrice finds her notebook and writes down more ideas. For Joys and Concerns, they could divide it up. People who wanted to light a candle of concern could sing “There Is More Love Somewhere.” The line “I’m gonna keep on till I find it” is perfect for it. She hasn’t figured out what to have for people lighting candles of joy. But she’s decided she wants “Come Come Whoever You Are” for the opening hymn. They could even start it up while people are still coming in and taking their seats. It’s a round, so people could keep it going. She especially likes the line, “Ours is no caravan of despair.” It makes her imagine the early days when Universalism was getting started, back when all you heard from your preacher was hell and damnation, only a few predestined to be saved, the Devil lurking everywhere. If you took a sip of ale after a long day working in the fields, the Devil was there. He was there if you wanted to dance a few steps to the sound of a fiddle, if you wanted to lean against a split rail fence for a moment, put down the bucket of water you were hauling and enjoy a breeze or a sunset. Patrice imagines some circuit riding preacher showing up one day, riding from village to village, stopping at farms and mills, calling out, “Salvation is universal, brothers and sisters! God has saved us all!” and people cheering, tossing hats and babies into the air.

She gets up to make a cup of tea. The television is still on in the kitchen. There’s an interview, an old man with an English accent, and as far as Patrice can tell, he’s famous for being eccentric. He doesn’t look too good, his voice is shaking, and he seems to have on garish makeup. The interviewer asks him what he thinks about sex change operations. “Good heavens, I’m much too old for surgery. Now if they’d had that procedure when I was young…”

The kettle starts to boil. Patrice is looking for a lemon and when she closes the refrigerator door she hears him say, “I certainly shouldn’t tell anyone about it, you know! One sees interviews with people who have had it done. There was that famous tennis player, and a pianist fellow, rather recently, too, and it amazes me that they tell the world about it. If I’d had that operation I shouldn’t have told a soul. I should have changed my name, got a whole new identity. I’d have moved to some small town and worked in a fabric shop and lived a nice peaceful life, and no one would know I’d ever been a man.”

Patrice adds honey to her tea and laughs. While she’s been imagining so many other lives, someone is out there imagining hers. She feels sorry for the old man, wanting so badly the things she takes for granted, the simple fact of being born female and never having to think about it. Being able to paint her nails without getting disapproving stares, being able to wear flower-print dresses and a delicate gold chain bracelet and have a soft, high-pitched voice. Actually her voice isn’t that soft and she realizes the old man probably isn’t imagining someone quite as loud as Patrice. Tomorrow morning she’ll look through the hymnbook for a song of thanksgiving; they should be sure to have one in the service. Maybe she’ll send the old man a postcard, Greetings from the fabric shop. Enjoying the life you’ve dreamed up for me. Thanks.

JulieAnne

Amanda sits behind the counter, trying to stay out of JulieAnne’s way while she waits on customers. They’re hoping for a lull so they can take some photos.

“So I tell my parents I’m thinking of going to a service over at the Unitarian church. You know the one in Northumberland?”

“Mmm hm,” JulieAnne says. She pours mocha syrup into a latte. Checks on the milk steamer.

“And they’re fine with it. So I ask, What are we, in terms of what church or whatever, and they say we’re UCC. And I say, So what does that mean? And they go, Well, it means we don’t burn anyone at the stake for believing differently than we do. And I’m like, Well, that’s good to know.”

The last person in line takes forever to make up his mind. Finally he decides on green tea and a maple pecan scone.

“So that was it. They’ll talk about anything else. Drugs they told me about long ago. Sex too. But religion?”

The customer walks away and JulieAnne hands Amanda the camera.

“Go over by that pillar and focus over here. What do you see? Zoom in so it’s just my shoulders up. Now what do you see? No, don’t take it when I’m looking straight at you.”

They waste a lot of time before JulieAnne gets the idea to stand Amanda in her place while she figures out things like angle, distance, degree of zoom.

“Okay, stand right here and take the camera. On this spot.”

“I love it. This is the most you’ve talked in years.”

“Wait till I get back to the counter. Okay, now what’s the light doing?”

“What’s the light doing? Do you expect me to understand that?”

Also she’s not sure whether she wants the background to be blurry or sharp. She likes the idea of glass behind her, the tumblers for iced coffee, bottles of syrup. Glass is hard and shiny and beautiful and she’s hoping it will make her look sophisticated, artistic. Something. She tries to imagine her mother looking at the picture.

Amanda’s got the hang of it. She’s moving around, ordering JulieAnne to turn this way, look in that direction. Mr. Graybill doesn’t even ask what she’s doing. Amanda has worked across the street at the sporting goods store for two years and she refuses to quit there and come work for him, but she gives him advice and he always takes it, like painting the walls deep colors and putting a quartz candle holder on each table.

He asks Amanda what she thinks about holding the poetry recitals out by the river during the summer months. She’s skeptical.

“Traffic from the bridge,” she says. “Too much noise.”

“How about Selinsgrove?”

“Isle of Que in the summer? Do you know what the mosquitoes are like?”

He stands near Amanda as if supervising the photo shoot. Now two sets of eyes and the camera are looking at JulieAnne.

Mr. Graybill tells Amanda, “I’ve been trying to get your friend here to sign up to recite something, but she claims she’s too shy.”

“I happen to know that JulieAnne likes poetry.”

“Amanda!“

Amanda ignores her. “Me, I have no patience for it.”

“Neither do I,” Mr. Graybill says.

She must have been watching them, she thinks, in the picture she ends up choosing to send to her mother. She looks amused and affectionate. She’s figured out just before the shutter clicked that the approving smiles they’re sending her way are meant for each other.

.

Larry

Larry sits at his kitchen table with a cold bottle of beer and a stack of poetry books that Molly has brought over. It’s hard to concentrate. He feels giddy with relief and gratitude.

Nothing’s wrong with his truck. She’s fine.

Turned out the gas cap was loose, that was all. No engine damage. No big repairs that would require Larry to get a second job.

He’d been on a back road he hardly ever drove, and on an impulse he’d turned in at a sign for Neil Kerstetter, Auto Repairs. The mechanic was an odd guy, said maybe a total of ten words. He was short and skinny, hunched over, never looked directly at him but Larry could tell he was thinking all the time. He knows the look: the guy has too much time to think. Wouldn’t even accept any money. Larry had tried to insist: “You took the time to check it out, you did your job.” The mechanic walked away, raised a hand briefly, gesture of goodbye or dismissal or both.

Larry leafs through a poetry book.

Molly, out in the living room, yells over to him above the noise of her TV show.

“How’s it going, Dad?”

“Fine, no problem.”

He starts at the front but quickly decides to flip to the back, figures the newer ones won’t be so hard to understand.

“What makes it poetry if it don’t rhyme?”

She mutes the TV.

“Dad, it’s not a rule. Lots of people write poetry that doesn’t rhyme.”

From the sound of her voice he can tell that people have known this for centuries, probably, and she must be thinking what an ignorant hick he is.

She never comes right out and says it, though. Cynthia never did either; he has to give her credit. Her family, though, different story. When he and Cynthia were together, her brothers and father kept referring to Larry as a high-school dropout even after he showed them his diploma. And then what a scandal, what a disgrace that this redneck had gone and got their daughter pregnant.

What they didn’t know was that Cynthia was the one who had chased after him. She didn’t mind his lack of education when his body was young and lean. We fit together so well, she used to say. He’s begun to understand what a novelty he was back then, how rebellious she must have felt to sneak off to his apartment at midnight after being at some fancy charity event with her parents. In the morning he’d find the jewels and designer dress draped over his jeans and work shirt.

Never a personal insult. No sarcasm or deceit or mind games. I just don’t love you.

He turns pages. Anything with sunsets or flowers makes his eyes glaze over. He remembers “The Highwayman,” some awful story about people tying up a girl and shooting her. He wonders if they still make kids read that.

“How about Robert Frost?” Molly calls out. “‘The woods are lovely, dark and deep’—no, I can’t picture you saying that with a straight face.”

I grow old… I grow old… I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled. He has no idea what it means but he likes the sound of it.

Something catches his eye. When you are old and grey and full of sleep…

“I like this Yeets person.”

“I know it looks like that, Dad, but it’s pronounced Yates.”

Yates. But one man loved… This can’t mean what he thinks it means. He tries to picture Cynthia in a bonnet and severe gray clothing, baking pumpkin pies, sewing by firelight.

“Honey?”

“Yeah?”

“Don’t laugh.”

“What, Dad?”

“What’s a pilgrim soul?”

She turns off the TV and comes into the kitchen and explains that pilgrims are people who go on pilgrimages, like in the Canterbury Tales. They travel a long way to get to a holy place.

It doesn’t really describe Cynthia, but it’s a cool poem anyway and he’s proud of his kid. She knows this type of thing, she’ll be comfortable at a place like Harvard. And that makes him think about how she’s leaving in another year. Even this summer it won’t be the way it used to be. The day she leaves for college a huge expanse of time, the rest of his life, is going to open up in the space where she used to be, and he’s going to curl up on the couch and cry. You could call it a time-honored method by now. A tradition.

And she’s a trouper, this kid; she’s already been trying to cheer him up. I’ll be back for Thanksgiving, she’d said the other day, a whole month at Christmas, spring break, almost four months for summer. You’ll hardly know I’m gone.

In the backyard Larry starts up the grill—veggie burger for Molly, ground beef patties for him. While he waits for the charcoals to get going he walks over to talk to Dirk, tell him the good news about the truck.

The only thing separating their backyards is the small parking lot behind the gun shop, but while Larry rents a ranch house on a small plot, Dirk lives in a farmhouse that’s been there for more than a hundred years. The house was decrepit when Dirk bought it and he’s been working on renovating it ever since, evenings and weekends, plus he built a summer kitchen out back and always has a huge vegetable garden.

Like most big guys, he moves slow, but somehow he’s always moving, and Larry follows him around as he breaks up a wooden crate into narrow shards, carries armfuls back to the garden to stake up the tomato plants.

“Soil looks good,” Larry says.

“Rototilled it late, though. And I tell you what—” Dirk’s voice gets loud as he pounds in each stake with a mallet. “There better not be no damn woodchuck in my broccoli this year.”

The more time Dirk spends on his garden and other projects, the less actual work he gets done in his house, which is fine with Larry and Molly, though they don’t tell Dirk that. They like the farmhouse the way it is, the tilted floor in the front parlor and the low, crooked threshold into the kitchen.

Larry’s not crazy about the bearskin rug and the dead animals mounted all over the place, but he likes Dirk’s stories, like the time he was out hunting and got tired and climbed up a tall pine to take a nap, and when he woke he looked down and saw a bear and her two cubs moving past the tree, not making a sound. Larry was relieved to hear he didn’t shoot them; maybe it was deer season or turkey or whatever, but it does seem to Larry that after Dirk met him and Molly he hasn’t done as much actual killing as he used to. Then there was the story of the peacocks escaping from the livestock auction out on Rt. 522—there’s Dirk at home minding his own business and he looks out the window and there’s peacocks perched in his trees.

“Have to run chicken wire all around here,” Dirk says, but he seems to be talking to himself, or maybe the woodchuck. He sounds irritable. “Do you know Trent Heimbach, buddy of mine?”

“I don’t think so,” Larry says.

“Had a stroke couple of weeks ago. Still in the hospital. And two days ago a guy at work, his wife had a heart attack, died instantly. She weren’t much older than me. No, I lie. She was my age, 52.”

“That’s awful.”

“What the hell, we ain’t even old yet.” He straightens up, rubs his lower back. “Used to be I had these cookouts on that property my folks got on Shade Mountain, back behind Paxtonville. We had picnic tables up there, barbecue pits. I ain’t talking no burgers and hot dog thing. I threw parties that lasted for days—we had roast pig, ribs, kettles of chili, I don’t know how many kegs of beer. We’d easily have eighty, a hundred people there at any one time. And I don’t know when that all stopped. Suddenly we was all too busy. Jobs, kids, I guess.”

“Wait a minute,” Larry says. “I think I went to some of those parties. They were yours?” He remembers sleeping on the ground, waking up to yet another friendly stranger handing him yet another beer. Women would pick the pine needles out of his hair and laugh.

“I must have been in high school.”

“Shi-i-it,” Dirk says, but he’s laughing. He throws an arm around Larry’s shoulder. “I don’t remember you from back then, man. But I guess we was both pretty fucked at the time.”

“We can do one now,” Larry says. “How about Fourth of July weekend? I’ll help you, I know how to grill. Between now and then, we’ll invite everyone we know. Or even anyone who looks familiar.”

“Hell, anyone who looks fun.”

Molly yells over to them. “Dad, I’m putting the burgers on before the charcoals burn out.”

“You should make some of those, what do you call, caramelized onions,” Dirk says. “Put ’em on the burgers. I saw it on that food channel.”

Larry brings over the food. He’s made enough for all three, and they eat their burgers and sliced tomatoes from Dirk’s garden at the picnic table. Soon it’s twilight, and the bats that nest in Dirk’s barn come flying out, like planes taking off one by one. This always creeps Molly out, but Larry loves to watch them. He and Dirk stand downhill from the barn, directly in the bats’ flight path. They’ve been doing this so long they don’t even cringe any more as the bats swoop down at them. They stand there and grin when they feel the breeze from the bats’ wings ruffle their hair.

∞

It’s starting to fill up already for the poetry recital. Three college guys come to the counter and JulieAnne puts her book down to take their orders: mochaccino with no whipped cream, double cappuccino but go easy on the foamed milk. The last one orders plain black tea and JulieAnne feels like thanking him.

One of the college boys has noticed the book and asks, “Are you going to read something too? What is it, Emily Dickinson?” They smirk and JulieAnne can feel her face getting red. “Look at her, it is Emily Dickinson!” and the way they’re trying not to laugh is worse than if they came right out and laughed in her face.

“Let me guess: ‘I’m nobody, who are you’?”

“No offense,” another one says, “we’re not making fun of you. Really.” With his elbow he jabs at his friend. “It’s just that, every high school kid on earth picks that poem. It’s been done to death.”

JulieAnne feels so stupid she can hardly look at them, but she hears another voice, someone waiting in line behind them.

“Did you like that poem when you were in high school?” he says to the college boys, but friendly, in a making-conversation way. One of them says yes, and this other man says, “It probably meant something to you then, probably explained how you felt about things. So why not let her feel that way, too, the way you used to feel?”

When she finally looks at the man, JulieAnne’s first thought is that, much as she loves black and white film, she’d have to use color film to do him justice, not only for that amazing long hair but those eyes, the kindness in them.