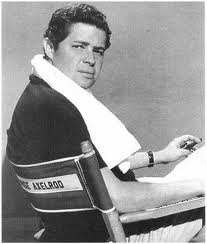

Running Through Beijing ought to be profoundly depressing. And yet it isn’t. Just the opposite: it’s uplifting, thrilling. It’s a form of meta-text: the fact that you are reading the book at all, the fact that the book was written and published, confounds the darkness of its message. The novel itself, with its sharp, detailed prose and vivid storytelling creates an exhilaration, a giddy hope in the reader that its characters can never share. —Steven Axelrod

Running Through Beijing

Xu Zechen, translated by Eric Abrahamsen

Two Lines Press, 2014

161 pages, $14,00

ISBN: 978-1-931883-30-8

Dystopian novels and films based on them crowd bookstores and multiplexes. These grim fictional futures, and hardy young people who struggle against contaminated environments and corrupt totalitarian governments that define our ruined future have become a favorite brand of escapism in an uncertain world. Things may be bad, these works seem to be saying, but they’re going to get worse. Partly a call to action but mainly an invitation to a cozy fatalistic complacency, novels and movies like The Hunger Games and Divergent want to lull us to sleep.

The novels written about actual dystopian societies, like Xu Zechen’s Running Through Beijing, have a different purpose: to wake us up.

From the moment that Dunhuang, the hero of Xu Zechen’s remarkable picaresque, returns to a Beijing sandstorm after a stint in jail for selling fake IDs, we know we have entered an ominously different world. The streets are buried in yellow dust — Dunhaung casually mentions boiling the tap water (it’s undrinkable otherwise) — and the police are so corrupt that bribes (of money or just cigarettes) are viewed as “fees,” standard as sales tax. As to the larger government, and the social structures of a civilized society, whatever light they shed they doesn’t penetrate the depths of Beijing’s street life as Xu Zechen describes it. These hustlers, prostitutes and con artists scuttle and scheme on the urban sea floor in the dark.

Dunhuang’s goals are simple: to make enough money selling pirated DVDs to bribe his friend Bao Ding out of jail and to find Qibao, Bao Ding’s girlfriend, and take care of her until the couple can be reunited. He knows nothing about Qibao but her name, and he’s only seen her from the back. It was a memorable view but not much to go on while searching through a city of almost twenty million people.

He’s not totally alone though. The first day in the city he meets a girl selling DVDs and buys a few, just to keep the conversation going. One of them happens to be Vittorio De Sica’s masterpiece The Bicycle Thief, the first of many film references that play in subtle counterpoint to the story. Rome stands in for Beijing, and the quest of Lamberto Maggiorani’s character for his stolen bike, essential for the job he needs to feed his family, resonates quietly with Dunhuang’s efforts to free Bao Ding from jail. In the underworld of Italy after World War II, just as in today’s China, the only real value is personal loyalty. Bao Ding let the police catch him so that Dunhaung could escape, and Dunhuang never questions or tries to shirk the obligation Bao Ding’s sacrifice imposes on him.

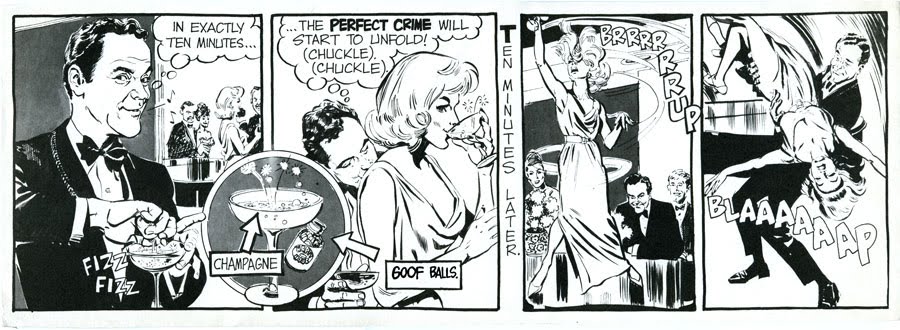

The DVDs these characters sell are more than an easy illicit commodity. They have expanded into a plastic jewel box philosophy, a code of ethics and aesthetics, illegally downloaded from America along with the movies themselves. Dunhaung echoes Hollywood con men from Paper Moon to The Grifters when he goes to dinner with the DVD girl, Xia Xiaorong, and claims that someone in the restaurant has stolen his money and his cellphone. The apologetic and embarrassed manager covers the meal and insists on buying them a few more rounds of beer. They emerge from the restaurant tipsy and triumphant.

It’s an awkward situation, because Xiaorong has an on-and-off boyfriend called Kuang Shan, who supplies her DVDs from his video store. But Dunhuang fits himself in somehow as part of the team. Hawking movies at the gate of the Agricultural University, Dunhuang recalls his earlier days selling fake IDs, revealing that world’s mundane anarchy and social dislocation:

Students needed fake IDs just like the rest of society. When it came time for the job hunt, in particular, they showed up in droves wanting fake transcripts and certificates of honor, the gutsy ones even asking for fake diplomas or degrees: polytech students wanting to be BAs, BAs wanting to be MAs, MAs wanting to be PhDs. It went the other way, too: older doctoral students wanting undergraduate student IDs for the half-price tickets to public parks.

Duhuang is cast out into that world again when Kuang Shan moves back in with Xia Xiaorong. No arrangement is stable in this world for very long. Dunhuang puts his head down and goes back to work. He moves from squatter’s digs in a disused diner to student lodgings near the university to a one room shack that at least offers privacy, building his clientele, dodging the police and occasionally sleeping with Xia Xiaorong, their stolen moments together unfolding “leisurely, like silent film from the twenties or thirties.”

Even their romantic moments conjure the astringent snap of Hollywood.

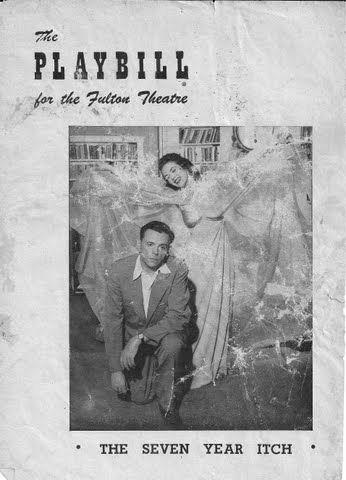

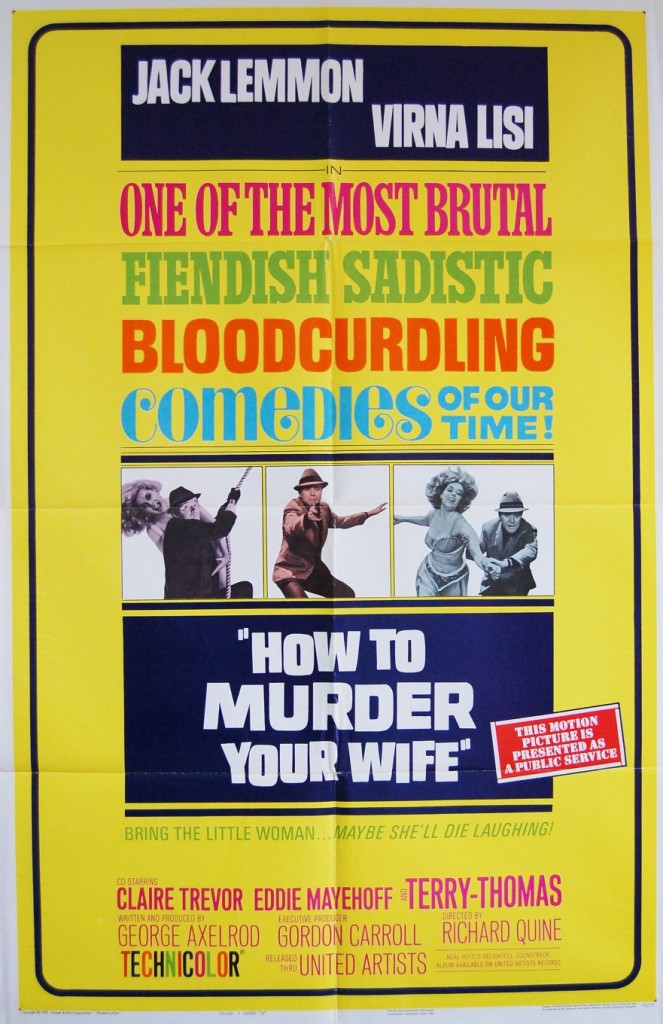

Dunhuang says, “What’s wrong with me saying you’re young, beautiful, graceful and refined?” (And Jack Lemmon says, “Did you hear what I said, Miss Kubelik? I absolutely adore you!”)

To which Xia Xiaorong replies, “A whole bowl of noodles can’t shut you up. Do the dishes!” (Like Shirley MacLaine’s four-word rejoinder that memorably ended Billy Wilder’s The Apartment: “Shut up and deal.”)

Eventually Kuang Shan and Dunhuang come to blows over Xia Xiaorong, but they wind up getting drunk together and wind up at the beginning of a wary friendship.

Xia Xiaorong suggests another familiar movie trope: the corrupt city girl longing to return to the country and a more innocent life. But that’s an expensive proposition. For the moment she’s stuck in the big city, caught between two men. When she gets pregnant, we never know for sure if Dunhuang is the father or not. In any case it’s hard to imagine raising a child in the chaotic world of Beijing street hustlers.

It feels like “a year of bad omens” to Dunhuang:

…he could see how the streets and the low residential buildings had all turned to the same dirt yellow color overnight, the way winter snows might blanket the earth. But the feeling was completely different; it made the dust covered buildings and streets look like ancient ruins, silent and deathly.

After a particularly nightmarish dust storm, Dunhuang starts scrawling advertisements for his business on the powdered windshields of parked cars. The trick works and he starts to notice other guerrilla advertisements stuck to hoardings and brick walls, mostly for fake ID sellers. Qibao sold fake IDs, or so Bao Ding had told him. Dunhuang makes the connection: all he has to do is call the numbers on these advertising stickers and keep asking for her.

It’s a long tedious process and in the meanwhile he keeps building his customer base. One girl lives so far away he has to buy a (stolen) bicycle, which itself gets stolen, doubling down on De Sica. Dunhuang winds up running everywhere (“They can’t steal my legs”), and soon he’s in marathon shape, which helps when the short-winded police give chase, though one of the scariest cops turns out to be a fake also, with his own counterfeit ID, just looking for an angle like everyone else.

And then, after more than three hundred phone calls, Dunhuang’s strategy for finding Qibao finally pays off. She turns out to be gorgeous from the front, also, a classic “bad girl” who smokes because she’d “die of boredom” if she quit.

“I barely remember what that jerk Bao Ding looks like,” she says.

“He remembers you.”

“Fuck, plenty of men remember me, Wouldn’t you remember me?”

Soon they are making love, mocking and copying the porn films they both sell on the street.

“You’re my girlfriend,” Dunhaung gushes.

“Whooo! Lucky me.”

But ominous events continue to pursue Dunhuang. When he and Qibao run together to the far district where the girl who buys his movies lives, she’s gone. The apartment is sealed and no one in the building has any idea what happened. People just disappear. No one is quite what they seem, even Dunhuang’s landlady, who turns out to be a Communist Party Secretary and threatens to turn him in when she discovers his cache of DVDs. Of course, she settles for raising the rent. “Stingy bitch,” Dunhuang mutters.

“What did you say?”

“I said, I’ll soon be rich.”

That joke is a small grace note of translation; one can’t help wondering how the rhyme worked in Chinese.

Qibao has little interest in her old boyfriend. Getting Bao Ding out of jail would take connections and Dunhuang doesn’t have any. “You’re not going to meet Buddha just by lighting incense,” she says. Instead of trying to buy Bao Ding out of jail, Dunhuang should save up his money and give it to his friend when he’s out of jail. “He’ll need it more then,” she points out, ruthlessly practical as always.

When Dunhuang visits Bao Ding, he agrees with Qibao. “Don’t even think about it, don’t kill yourself on my account, either way it’s cool. Just bring me a carton of smokes from time to time.” Bao Ding’s sense of loyalty is more impulsive – getting arrested so that Dunhuang could escape, or jumping in to defend a friend who was getting beaten up in jail.

Their world isn’t kind to long range plans.

When Dunhuang returns to Beijing he goes directly to Qibao’s house, but she’s not there. He waits outside for her through most of the night and when she finally shows up, startled to see him, he’s furious. She claims to have been out with friends. He knows she’s lying but he doesn’t have the heart to dig for the truth. Instead, he stalks off. She follows him.

They walk for hours, Dunhuang smoking compulsively and flicking the butts into the street, Qibao following him, picking them up. It’s a bizarre interlude, a hieratic ritual of improvised self-abasement: a concubine, serving the emperor. Her gesture simultaneously evokes the formalities of a bygone era and mocks them. Or perhaps she is just mocking herself and Dunhuang and the very possibility of a structured rational society, however oppressive. In any case, the final offering, the handful of spent cigarettes, is enough to defuse Dunhuang’s anger and win him back.

Spring comes to Beijing and fortunes change: Kuang Chan’s video store is closed by the police, and Dunhuang has to find a new supplier. The pal Bao Ding rescued in jail turns out to have political connections. A few phone calls, and Bao Ding is back out on the streets. When Bao Ding goes to a whorehouse, one of the prostitutes turns out of be Qibao. He tells Dunhuang the truth, and after a screaming, slapping match in the street, Dunhuang breaks up with her.

But when Qibao is busted, Dunhuang bails her out. Loyalty comes before every other emotion. They wind up together, as do Xia Xiaorong – now pregnant — and Kuang Shan. But Beijing doesn’t allow for happy endings, and these characters take “ever after” ten minutes at a time.

The last moments of the novel sum up its theme and story in a single heartbreaking image, a visual jueju poem that seems to encapsulate the past and the future of these trapped, doomed children of the street.

The set up is simple and familiar, echoing the events that first landed Bao Ding and Dunhuang in jail. Kuang Shan and Xia Xiaorong are selling DVDs in the street, now reduced to competing with Dunhuang for sales. A police raid explodes and Dunhuang draws the cops away from his friends. We know his running skills by now. He loses the police but when he returns Kuang Shan is gone and Xia Xiaorong is sprawled on the sidewalk in a puddle of blood. In the violence of the raid she has lost the baby, and her DVDs – brightly colored plastic squares showing the life these kids have aspired to and emulated – are scattered across the dirty pavements: gaudy, mendacious trash.

This is how authentic dystopian novels end, from We to A Clockwork Orange to Oryx and Crake: the characters defeated, the revolution a chimera, all hope lost. No warrior princess or cunning hero is going to save the day. The day was lost before it began.

Running Through Beijing ought to be profoundly depressing. And yet it isn’t. Just the opposite: it’s uplifting, thrilling. It’s a form of meta-text: the fact that you are reading the book at all, the fact that the book was written and published, confounds the darkness of its message. The novel itself, with its sharp, detailed prose and vivid storytelling, creates an exhilaration, a giddy hope in the reader that its characters can never share.

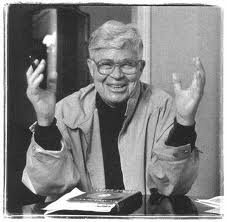

And so does Xu Zechen’s life. Born in 1978, he got a master’s degree in literature, and edits a prominent literary magazine, People’s Literature. He has won prizes and traveled abroad, serving as a writer in residence at Creighton University in Nebraska and distinguishing himself in the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. And now Xu Zechen’s tough, unsentimental novel has been translated into numerous languages, including this elegant English version by Eric Abrahamsen.

It might cheer Dunhuang to know, as he moves beyond the last page, picking up Xia Xiaorong’s DVDs and helping her to the hospital, looking out for the ever present, ever-corruptible cops, taking care of himself and his friends as best he can, with no hope for the future beyond the Hollywood vision, the pirated movie playing in his head, that his humble, anonymous story has finally been told, and that the whole world is listening.

They might even make a film out of it someday.

And if they do, you can be sure Dunhuang will be selling pirated copies of it on the street.

— Steven Axelrod

Steven Axelrod holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of the Fine Arts and remains a member of the Writers Guild of America (west), though he hasn’t worked in Hollywood for several years. Poisoned Pen Press kicked off his Henry Kennis Nantucket mystery series in January, with Nantucket Sawbuck. The second installment, Nantucket Five-Spot, is scheduled for 2015. He’s also publishing his dark noir thriller Heat of the Moment this summer, with Gutter Books. An excerpt from that novel appeared in a recent issue of “BigPulp” magazine, which will feature his post-modern horror satire The Risen in its upcoming “All Zombie” issue. Steven’s work can be also be found on line at TheGoodmenProject and Salon.com. A father of two, he lives on Nantucket Island where he writes novels and paints houses, often at the same time, much to the annoyance of his customers. His web site is here.