Louis Armand is no stranger to the faithful readers of Numéro Cinq. At the end of 2013, we published an excerpt from Cairo, a swirling novel that found itself shortlisted for the Guardian newspaper’s 2014 Not-the-Booker Prize. And we’re pleased to now present a snippet from Armand’s latest, Abacus. Publisher Vagabond Press calls Abacus, “A decade-by-decade portrait of 20th-century Australia through the prism of one family … a novel about the end times, of generational violence and the instinct for survival by one of Australia’s leading contemporary poets.” Like his earlier novels, Abacus sinks its teeth deep within an environment—this time Armand’s homeland—providing the reader with a visceral understanding of the territory, and thus a greater empathy for the individuals who roam each page.

This excerpt is a condensed version of a later chapter in the novel, titled “Lach,” though it was originally titled “King Shit.” In the following, childhood carelessness butts heads with the lingering aftereffects of wartime trauma. This is, of course, just a taste of what Armand has to offer. For the full picture, seek out the novel itself. It’s well worth the time.

— Benjamin Woodard

.

The morning the spastic girl walked out in front of morning assembly with her undies down, bawling for her arse to be wiped, was the last time they ever had to sing “God Save the Queen.”

It was March and the Drover’s Dog had just won a landslide victory for the ALP in the federal election. A republican was made Governor General. “We’ve got our own bloody anthem,” Lach imagined him saying to the knobs at Buckingham Palace, Sir Bill, because you couldn’t have a Governor General, even Billie Hayden, who wasn’t a “Sir.” Just like their headmaster, Crazy Crittendon, who went purple when the spastic girl came up in front of the whole school like that, skid-marked knickers round her ankles, you had to call him “Sir” if you didn’t want a caning or detention for a week.

“Bwoo! Mnaaa!” the spastic girl wailed.

The teachers were all standing out the front singing the nation’s praises while all the kids just mumbled along not knowing the words, they’d only ever heard it on the tellie when someone on the swimming team won a medal at the Commonwealth Games. “Australia’s suns let us rejoice,” what was that supposed to mean? But when the spastic girl did her thing everybody suddenly went silent. Three hundred kids sweating under the hot sky in turd-brown uniforms, waiting to see what Old Cricket Bat’d do next.

Which was exactly the moment Buzik, standing in the middle of the back row, chose to crack the loudest fart in history.

*

“They make a lie so big, no-one can see it,” Wally Ambrose said once. Reg could hear the old bloke’s voice in his head clear as day. Could see him, too, sitting on the verandah, handing him a model spitfire. Who knew how old he was back then? Wally’s voice came to him while he was sitting in the parking lot at the Holsworthy Army Base, across the river in Liverpool, waiting for Eddie. They’d called him in for some medical checks. Ever since Eddie’d come back from Vietnam, he’d been having trouble sleeping at nights, couldn’t breathe properly, kept getting headaches, skin rashes, sometimes couldn’t feel his hands.

The doctors said there was nothing wrong with him, but one doctor thought it might be something to do with the war. Agent Orange. The stuff the Yanks dropped by the metric tonne to kill-off jungle cover along the Ho Chi Minh trail. There’d been talk in America of child birth-defects. Both of Eddie’s kids had the worst kind of asthma. As a matter of course the Fraser government denied everything. The army wanted their own doctors to have a look, so Eddie got the call and Reg’d offered to drive him over to the base, knowing his brother’d be too shook-up afterwards to manage the traffic alone. The vets had been bullshitted all along the line, it was just a question of time before enough of them cracked and took matters into their own hands.

Finally, now Fraser’d got the boot, there was talk of a Royal Commission. “Yeah,” Eddie said, “Royal fuckin’ Whitewash.” Reg switched on the radio and got Rex Mossip in mid-stream, then dialled across to a different station — Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs — and tilted his seat back, closing his eyes with the music on low. Politics didn’t mean anything to him anymore. He had enough drama of his own to worry about, a fucked-up marriage, a smartarse kid and a job that had him pegged for a cardiac before he hit forty. He never did get called to the bar, working his way through the NSW Public Service instead, “faster than a rat up a drain.” It didn’t take long to earn a name for himself as a hatchet-man. They sent him to balance the books in every dysfunctional underperforming redundant backwater of government. From Attorney General’s to Education to Consumer Affairs and finally Premier’s, kicking heads at the personal behest of Neville “Wran-the-Man” on a Grade-11 salary. Another ten years, he could sign-off in style with a harbour view.

But Reg wanted out. Besides, there was nowhere left to go, he’d already bagged the number two job to the biggest hatchet-man in the service, Gerry “Bottom of Darling Harbour” Gleeson. To get his job, he’d have to stiff the fucker. Only alternative was to bide time till the next election and hope Nifty Nev took a nose-dive at the polls, but even then. Besides, in this game, you sat still and you were a dead duck.

Reg dialled-up the volume on the car radio so as not to think about his glorious future any more. A commercial ended and he found himself listening to Acker Bilk. He stabbed at a button blindly and got a different station. “History never repeats,” someone sang over background guitar in a high nasally voice, “I tell myself before I go to sleep…” He made a wry grin, seeing himself exactly like that, stuck in a vicious circle of his own making and trying to bullshit his way out of it. Bullshitting a bullshitter. It was a sure way to fame and glory, peace and happiness, whatever the fuck he’d been pretending all these years he wanted out of life. And what did he want? He didn’t know. To be King Shit maybe.

There was a tapping on the passenger-side window. Reg lent over and flipped the handle. Eddie pulled the door open and slumped into the seat. His face looked sunken and puffed-out at the same time, dark around the eyes, bloodshot. His fingernails were yellow from chain-smoking, to give his hands something to do so he wouldn’t scratch all the time. Had to drink himself to sleep, too, because none of the pills the doctors gave him worked. “Fucking placebo shit.” Whatever they’d been sprayed with over in ’Nam had its claws in deep and wasn’t letting go.

“What’d they say?”

“Usual,” Eddie said, rolling the window down and reaching for the car lighter, a Winfield already wedged in the corner of his mouth.

“Any chance of compo?”

Eddie dragged on his cig, killing half of it in one go while plugging the lighter back in the dash.

“Buckley’s, mate,” he said, exhaling a long plume of smoke out the window. “Only way the government’s forking-out’s if someone proves liability. But to prove liability, they’d hafta prove they used the stuff in the first place. And since they deny the stuff even exists, we may as well just hand ourselves straight to the head-shrinkers, ’cause as far as the experts are concerned, this whole Agent Orange shit’s in our fuckin’ imaginations.”

*

Buzik had freckles and was the shortest kid in the sixth grade, though he acted like he was some sort of Daniel Boone. He lived on Kingarth Street, near the park ruled by an ancient magpie called Big Eye. A strip of concrete in the middle of the park served as a cricket pitch, but no-one ever wanted to field at long on, because that was right under Big Eye’s tree. Legend had it Big Eye once tore a ball to shreds mid-air on its way for a six. All that was left of it were bits of string and leather and scabby cork raining on the boundary. Or maybe Buzik just made that up.

Short-arse though he was, Buzik was the undisputed king of the tall tale. He could cook-up an adventure out of anything. One day he came to school with a copy of Huckleberry Finn and decided their gang was going to build a raft. Buzik, Lach, Robbo and Robbo’s lisping kid brother, White-as-Wayne. He drew up the plans from a Scout’s handbook. To make a raft, he explained, first you had to find some empty forty gallon drums, then some timber to make a frame, some rope to square-lash the drums to the timber, and finally some planking to build a deck. There was a dam just off South Liverpool Road he knew about, past Wilson’s, all they had to do was find the stuff they needed and get it there, then they could lie about on the water pretending they were floating down the Mississippi.

The rope was the easiest bit, the drums were trickier. Buzik found a dozen lying around among the car wrecks in the wasteland behind the Liverpool Speedway, but most were rusted full of holes. They managed to salvage four that looked like they’d float, but the problem was how to get them across to Wilson’s — you couldn’t haul a forty gallon drum on a BMX. White-as-Wayne said they ought to use shopping trolleys, so they hiked across to the gully where the drain at the end of Orchard Road emptied out, to see what they could find. People dumped all sorts of stuff there, but especially shopping trolleys. There was always at least one upended in the grass whenever they went by on the way to school.

You’d never know the dam off South Liverpool Road was even there. It was trees and dense bush all the way along the roadside with a three-strand wire fence. But if you climbed through the fence at the right spot there was a path into the undergrowth that about fifty metres from the road forked left and right, and to the right it ran smack into the reeds along the shoreline of a wide dam. To the left, the path eventually found its way along the top of the dam wall, a berm of compacted earth with a steep run-off into a ditch where a farmer’s septic tank overflowed. You could follow the path half-way around to the other side of the dam or veer left again where soon you came across old chicken coops stacked high against the side of a barn, a tower of corrugated rust with a wrecked school bus parked in front of it. On the other side of the bus was the farmer’s house.

The four of them must’ve made a queer sight ferrying old diesel drums balanced on a shopping trolley across South Liverpool Road, then wrestling them through the fence and into the bushes, but who would’ve seen them? White-as-Wayne stood sentry on the corner of Wilson’s and shouted the all-clear when no cars were coming. And whenever one did, they dived for cover among the weeds that grew waist-high. The trolley and the drum were just more of the usual wreckage camouflaged into the scenery. It took all morning, but eventually they had the drums stashed in a clearing under the canopy of a low-hanging she-oak. Then they went off scavenging.

Buzik, crawling on his belly, snuck into the creaking barn and found a cool-box full of beer bottles. He came back with six of them slung inside his shirt. Robbo and Lach meanwhile had wandered off onto the other side of the dam and found some corrals and a pile of timber that’d been cut once upon a time for fence posts. The posts looked ideal. White-as-Wayne guarded the drums. Buzik had already cracked one of the bottles and was down by the water sucking beer when Robbo and Lach came back with the news. The rest of the beers were bobbing at the edge of the reeds, keeping cool. White-as-Wayne was busy climbing a tree.

“Where’d you get the Tooheys?” Robbo said.

“That’s for me ta know ’n’ youse ta find out,” Buzik grinned.

They parked themselves beside him and cracked a couple of more bottles and sat there drinking thoughtfully.

“This stuff tastes like piss,” Lach gagged.

“In one end, out the other,” said Buzik and proceeded to whip out his dick right there in front of them and, holding the bottle of Tooheys upended in his mouth, arced a stream of piss into the water.

When the beer was finished the four of them tramped back to the horse yards to collect the timber Robbo and Lach’d spotted.

“Jesus Christ,” Buzik said, trying to haul one of the fence posts off, “this stuff weighs a tonne.”

“Yeah,” Robbo gloated, “solid as. The raft’ll never break, no matter what.”

“Give us a hand, will ya?”

Two-by-two they carried and dragged the wood all the way back around to the other side of the dam. The dam was bigger than it looked. It was getting dark by the time they’d hauled the six posts they needed. Four for the frame to lash the drums to, and two for cross-beams to keep it square. There was an old tarpaulin in the barn, Buzik said, which they could use for a deck, and even a couple of oars that must’ve belonged to a row-boat once. They trudged off home in the twilight and pulled the splinters form their hands and next morning went back for the canvas and oars and set about putting Buzik’s grand design into effect.

Lashing the posts to the drums took some finesse, the rest was easy by comparison, it was just a question of getting the ropes tight enough so the whole thing wouldn’t just come apart. Then they had to cut a path through the reeds down to the water. They cracked a few more of the farmer’s beers and poured some over the raft to christen it. The Graf Spee, Buzik wanted to call it. But in the end they just called it “The Raft.” On the stroke of midday they pushed off. It was heavy work, hauling their contraption out of the clearing and down the bank. Then all of a sudden it slid out into the water and down, down, catching the sunlight faintly through the murk. The raft came to rest about a metre beneath the surface, a faint trail of bubbles rising from the drums, the hardwood posts making immobile shadows beneath the canvas as it flapped in the cold current.

*

Robbo’s house was a block east of Buzik’s, on Trevanna Street. Lach lived on the other side of Whitlam Park. All three of them played footie for the under-11s. Maroon-and-blue were the locals colours. The school colours were yellow-and-brown, like flying-monkey guano Buzik said. On weekends when they weren’t kicking a ball in the park or roaming about on their bikes, they’d hang out at Robbo’s place. If no-one else was home they’d stuff about on the phone impersonating Robbo’s neighbour, ringing the taxi companies or the pizza delivery man for giggles. Their record was three taxis at the same time, parked one behind another outside the Hogans’s front gate, honking their horns. Mr Hogan knew who the culprits were and bawled at them over the side fence. Said he’d kick their arses so hard his boot’d poke them in the back of the teeth. So then they phoned a towing service, an undertaker, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses as well.

There were three Roberts brothers, the eldest played guitar in an AC/DC cover-band and was the stuff of legend. White-as-Wayne was in fourth grade, short and skinny with blond hair and a lisp. They teased him a lot but let him tag along, though he had to swear on his life not to tell anyone about The Raft.

Buzik was never one to let a minor setback get in his way, so the weekend after their first effort sank they went back with their shopping trolley and hauled four more empty drums up to the dam. This time they found a couple of planks from a scaffold on a building site and tied them crosswise like an outrigger. They pushed off and this time it kept afloat. White-as-Wayne, who was the lightest, sat up front with Robbo at the back. Buzik and Lach, one oar each, sat on the outside drums and rowed, careful to avoid the snags.

They could’ve floated around the dam for days, it seemed to go on forever, one fjord opening onto another, and yet you could’ve walked the long way around it in an hour beating through the bush.

“There’s eels,” Buzik said, peering down into the black water.

White-as-Wayne pulled his feet up and crossed his legs at stern. Robbo stared glumly over the side.

“I’m goin’ in,” Buzik said, “see if I can catch one.”

He propped the oar on the cross-beam and stood up on the barrel. They were all wearing only their shorts. Buzik bounced on his feet, jumped, did a donkey kick mid-air and splashed down into the black. The outrigger swayed and bobbed. Lach paddled it in a half-circle towards one of the fjords. The undergrowth came down thick to the water’s edge, overhung by dangling willow trees. Dragonflies hovered. Skaters raced about on the surface. It was a warmish spring day and the air was full of insects. White-as-Wayne shivered.

“Hundreds of ’em,” Buzik shouted, flinging his head above the water. “Huge. Big as morays!”

“Bullshit,” Robbo moaned.

“What we need’s a fishin’ line,” Buzik said, catching hold of the port-side drum. “A bloke showed me ’ow to do it. You catch eels wiv a pin, tied to the line, like this.” He made gestures with his hands none of them could decipher. “We’ll catch ’em ’n’ roast ’em on a fire.”

Lach was busy with a pencil working on a map of the dam. He had a square of paper in a plastic bread bag which he kept wrapped up and tucked in the waist of his shorts. Right now he was adding the fjord they’d drifted into. There were roots jutting out from the bank and slimy reeds under the water and a tree stump with a skink lying flat atop it with only its head sticking up.

“What d’ya reckon we should call it?” Lach said.

“Call what?” Robbo shouted.

“This place,” he gestured with his pencil at the fjord in general.

“Something different from the last place,” Buzik said, clambering aboard. “Like Fuckwits’ Cove. Or Silly Cunts’ Bay.”

“Yeah, but it ain’t a cove, or a bay neither.”

“Haiwee Quack,” lisped White-as-Wayne.

“The Arsehole’s Arsehole,” crowed Robbo.

“You bastards’re no help. We’re meant to be explorers. Yer s’posed to give things proper names.”

“What like?” Robbo said. “Sydney Harbour?”

“Call it Lizard’s Bight,” Buzik said, grabbing his oar and pushing off from the tree stump, so they wouldn’t get snagged on its roots.

The outrigger drifted around on its axis. Lach stuffed his map in his pants while Buzik manoeuvred himself into position and they worked the paddles out to deeper water.

“Who d’ya reckon’s better looking, Jenny Carter or Helen Heckenberg?” Robbo said from the back.

“Carter’s a stuck-up bitch,” Buzik yawned, “’n’ Heckenberg’s an old stuck-up bitch.”

“Helen Heckenberg’s the biggest piece of class in these burbs,” Lach drawled.

“Helen Heckenberg’s got melons out to here,” said White-as-Wayne, hands groping the air in front of him.

“How d’you know?” said Robbo, splashing water at his younger brother’s back.

“Piss off!”

“Jenny Carter’s got a head like a sucked mango,” Buzik yawned again, “but I’d still root ’er.”

“You’d woot anythin’,” lisped White-as-Wayne. “You’d even woot one a tha spazos at school!”

“I ’ope ya can bloody swim,” Buzik growled, launching himself between the crossbeams and knocking White-as-Wayne right off his perch.

The two of them thrashed around in the water for a while before Buzik swam away towards the shore where their secret base was. White-as-Wayne clung to the drum at the head of the outrigger, sulking. Lach climbed onto the middle of the cross-beams and paddled legs-astride.

“Don’t ya reckon Jenny Carter’d be a real goer, but?” Robbo said.

“Bit skinny,” Lach said pensively, “’n’ she’s got more freckles than Buzo ’as. They might be related, you never know.”

“Yeah, but Buzo’s sister’s fat’n’ugly.”

And as if on cue the three of them started singing, “Who got beaten wiff tha fuggly stick? Buzo’s, Buzo’s. Who got beaten wiff tha fuggly stick? Buzo’s sister did!”

*

Lach had never seen his father fall down drunk before, but that’s what he did after the taxi driver helped him in the front door the night Lach and his mum stayed up to watch The Battle of Britain on the old twelve-inch black-and-white tellie. Midnight matinee. In the movies, people drank coffee when they had too much booze, to wake them up, so Lach took the matter in hand and brewed up a pot while his mum tut-tutted over the prostrate figure in the hall. He made a couple of guesses at how much of what went where and came back a few minutes later with a scalding cup of black sludge.

Various enigmatic expressions coursed his mum’s face as she watched him kneel down beside the groaning lump Reg Gibson made on the floor and with commendable effort pour the vile stuff down the paternal throat, not spilling a drop on the new carpet. Until, that is, Reg Gibson screamed, hurling a mess of steaming black bile down the length of a polyester suit that looked like it might dissolve on impact.

Lach was on his feet in the blink of an eye, fleeing on instinct, before his father’s paws could get a grip on some part of him and throttle him blue. The drunken mass heaved bellowing into life and stumbled up, ricocheting between the walls. What Lach remembered was the hallway getting longer and narrower the harder he tried to run and Reg Gibson charging up behind him, mad as a bullock, fumbling blind at his belt buckle and then the singing of the leather as it swung through the air. He remembered his mum’s face, just the way it always was, blurring at the edges.

Somehow he made it to his room & dived under the bed as the blows began to rain. Just because of the coffee! And then something went crash and all was silent before the light came on. As quietly as he could, Lach manoeuvred among the junk under his mattress and peered out. Reg Gibson seemed to be standing stock-still in the middle of the room. The room somehow had been altered by the silence. With utmost stealth, Lach inched forward for a better look. His father, belt hanging from his right hand, arm limp at his side, was teetering as if in a trance, staring wide-eyed at the floor.

There between Reg Gibson’s feet were the remains of a model spitfire, the one Lach’d found in a box on the top shelf of the linen press at his Nana’s house. A pair of green-and-brown camouflaged wings with the red-and-blue bullseye decal projected from a wrecked fuselage. Like in The Battle of Britain, when the Heinkels were blitzing the RAF airfields. Only instead of a hundred-pounder, it was Reg Gibson’s Florsheim that did it. The blind rage seemed to’ve drained out of him, replaced by an emotion Lach was unable to decipher. The lull, perhaps, before an even more terrible storm.

He’d meant to keep the spitfire a secret, but in his excitement before the film he’d taken it out of its box to look at and see if the wheels still turned. Behind the smudged cockpit window was a pilot done in so much detail you could even see his eyes. But there was no sign of the pilot now. Bits of the cockpit lay scattered on the floor. The gun sights. The radio set. A shattered prop, piston rods, landing gear. Then all of a sudden Reg Gibson booted the wrecked fuselage across the room and stomped out, muttering how it served someone right, only Lach couldn’t hear who it served right and he huddled there, under the bed-head with his feet touching the wall, and shivered, trying not to cry.

*

Uncle Eddie kept all his stuff from Vietnam in a drawer in the back bedroom at Nana’s house on Dartford Street. Slouch hat, poncho, tie, a couple of belts, mozzie net, jungle greens, dress uniform. Whenever he could, Lach snuck in there to try everything on in front of the mirror, like a midget on parade. He asked Eddie if he could take some of the stuff home and Eddie shrugged.

“Just leave the hat. Ya can do what ya like wiff the rest of it. It’s only there ’cause Mum kept it.”

“What’s special ’bout the hat?”

“Nothin’.”

Lach couldn’t make sense of that so gave up trying. His uncle’d always been a bit strange, though they didn’t really get to see him very often. He lived way out in Campbelltown on a dead-end street. It was the war that made him like that, his mother explained. Lach wondered how she knew.

He took the belt and poncho and mozzie net up to the dam, for the secret base they were making in the clearing under the she-oak where they’d put the raft together. They’d woven branches into a camouflage that hid the whole thing from view, and hung stuff inside, trophies from their raids on the farmer’s barn and the old school bus, bottles of beer, centrefolds from mildewed porno magazines, hubcaps. Lach draped the mozzie net over one side. Buzik and Robbo dragged a couple of car seats over from the back of the Speedway, stinking of sump oil. They scrounged some ratty drop-sheets to spread over them. The ground was littered with dead cicada skins, like the husked shells of aliens zapped by a secret particle beam, the death ray or the doomsday box.

White-as-Wayne dug up a billycan from somewhere and they built a fireplace out of rocks, close to the water, with a smoke hole in the canopy. Buzik scooped dam water into the can and a fistful of gum-leaves, to make billy-tea. They sat around waiting for it to boil, smoking tubes of coiled-up bark as if they were cigars. White-as-Wayne gazed at the pin-ups. Christy Canyon, Sharon Kane, Amber Lynn. Big hair and parted lips making the kind of invitation a ten-year-old’s nightmares are made of. Robbo absently flicked dead cicada skins into the fire and watched them flare and crackle and dissolve into white flame. Buzik blew out a smoke ring that rose up through the twilight of the branches. Faint shafts of sunlight filtered down.

“We should bring a girl up ’ere,” Buzik said at last.

“What’d a you want a girl for, it’d just ruin it,” Robbo said, pulling the legs off another husk.

“No girl’d come ’ere anyway,” said Lach.

Steam gusted up from the billycan. White-as-Wayne crawled over with a stick and lifted it off the coals. There was a sharp hiss.

“Don’t spill it all over the bloody place,” Buzik growled.

“It ain’t spilt,” White-as-Wayne protested.

Robbo set out the tin camping mugs and went to pour the tea.

“Yer s’posed ta whack it wiv a stick first,” Lach said.

“Wot’s that for?” said White-as-Wayne.

“Makes it taste right or somethin’. Me uncle said that’s wot you’ve gotta do when ya make billy tea. Gotta whack it wiv a stick.”

White-as-Wayne tapped the side of the blackened billycan with his stick. Lifted the lid and peered inside. Shrugged.

“Can’t see tha diffwence,” he said.

Gingerly Robbo poured the yellow brew into their mugs. Buzik reached over and took one, tossing the remainder of his bark roll into the smouldering campfire. All four of them blew into their mugs to cool the tea, stirring it sluggishly with their breaths. Buzik was the first to taste it, his face gave nothing away though. When Lach tried it he almost spat it straight out. Robbo had a sip.

“Jesus,” he gagged, “it tastes like friggin’ tadpole piss.”

They all hooted with laughter. Buzik splashed his tea on the coals.

“Give us one a them beers,” he grinned.

Robbo pulled out his Swiss Army knife with the bottle-opener on it and cracked three stubbies, passing them around. Only White-as-Wayne kept hold of his mug, gazing into it and swishing it about like he expected to find something alive in there, some sort of primordial guppy perhaps.

*

The art was in somehow not gauging your ribs with the valve when you slid up through the tyre tube. It was mid-morning before they started across the river to the island. “Wide as the Mississipi,” Buzik said. They had to dodge the water-skiers spraying up plumes of yellow-brown and the speedboats slapping their bellies on the water as they throttled up and down between the bridges. Lach’s uncle, Pete, owned a caravan on the Hawkesbury. He’d sit out under the awning in a deckchair with an esky of beer and get sunburnt feet. With a little persuasion he let the kids spend the weekend as long as they kept out of his hair. Uncle Pete’s mates usually showed up around five and barbequed some prawns and sank Tooheys. “Get yerself some fish’n’chips,” he’d say to the kids, handing them a couple of dollars and waving in the direction of the shops. Deep sea bream with salt and vinegar on the chips, wrapped in newspaper, though really it was shark. They’d sit down under a jetty, tossing the butt-ends of chips to the guppies mouthing about in the shallows.

The sand on the shore of the island was dark and wet, with a bog smell and mangrove roots worming up through it that stabbed into their feet. In from the water the ground turned solid and dirt paths wound through the undergrowth, so thick you couldn’t see more than a couple of metres at a time. They left the tractor inners by the shore and went exploring, but couldn’t get to the other side of the island, all the paths seemed to wind back. And then, starting out of nowhere, was a clearing with a tin shack and voices. The voices sounded drunk, a couple of men and a woman, so the two kids slipped away again into the bushes.

“Wouldn’t it be awesome if we had our own island,” Buzik whispered, “wiv a house on it ’n’ everythin’. ”

Of course they hadn’t been alone in taking possession of the dam off South Liverpool Road, either. A gang of local kids had set up headquarters in the old school bus in front of the farmer’s barn. When they’d discovered the secret base Buzik, Lach, Robbo and White-as-Wayne had built, they smashed it up and burnt the mozzie net and poncho and centrefolds and slashed the car seats and scuttled the “raft” by unscrewing the caps on the forty-gallon drums. “I’ll chop their bloody skulls in ’arf,” raged Buzik, who went and broke all the remaining windows in the wrecked school bus, but he never found out who the other gang was.

When they got back from the island, Uncle Pete was asleep under his awning, fist clenched around an empty beer bottle. With nothing better to do, Lach and Buzik grabbed a couple of Pete’s fishing lines and a bait box and wandered down to one of the jetties to see what they could catch. Past the jetty was all thorny blackberry bushes hanging over the water. Someone had snagged a lure in one of the bushes and Lach spotted it glinting in the sun. With a scaling knife in one hand he waded down the jetty to cut it free. Buzik meanwhile was scooping among the green slime that wafted off the jetty for fresh bait. He caught some guppies and threaded them on a hook and was just casting out when Lach slipped arse over tit on the algae, only just failing to disembowel himself with the scaling knife but almost taking his thumb clear off.

“Ya silly bugger,” Uncle Pete said, laying a role of sticky plaster aside, “yer old man won’t be too impressed.” He’d rinsed out the flap of skin hanging from Lach’s thumb with Detol then stuck some gauze on it and wrapped the whole thing in plaster. “Lucky it ain’t too deep or you’d need stitches.”

There was blood everywhere, it looked a lot worse than it probably was. Lach was all pale around the gills, with his head leaning against the side of the caravan. Uncle Pete faked a tap on his chin.

“You’ll be right,” he grinned, gathering up the first aid kit. “Just a scratch. Next time, do it proper ’n’ see if ya can cut yer ’ole arm off.”

The sun had gone down and there was a halo of bugs around the kerosene lamp slung under the awning. Buzik lounged in one of the deckchairs breathing in the river stink. Lach stared at his cartoon thumb swaddled in plaster.

“Reckon there’s bull sharks in the river?” Buzik said. “Wouldn’t wanna go in there bleedin’ like that, they’d smell it ’n’ come after ya.”

“Ain’t no sharks in the river.”

“There is. I saw it in a documentary.”

“You kids talkin’ bull again?” Pete lurched down the caravan steps. He held out a couple of longnecks. “Now don’t tell yer folks, ’cause they mightn’t like it.”

Buzik smirked like an idiot.

“Thanks Mr Gibson,” he said, grabbing one of the beer bottles.

“Call me Pete,” said Pete.

He handed the other one to Lach who sat there with his wounded thumb sticking up, holding the bottle in both hands like it was Communion.

“Cheers,” Pete said, settling back. “Youse fancy some prawns fer supper?”

*

“Aw, Miss,” Lach moaned.

It must’ve been thirty-five degrees, but still they had to stay in the classroom and finish the problem that’d been set on the board.

“And if you don’t get it right,” said Mrs Hajek, “you’ll stay here all afternoon until you do.”

The class fidgeted with their books. Buzik fired a wad of chewed up paper from his pea-shooter at the back of Robbo’s head. Robbo, marooned in the front row, tried to look diligent as the Dragon Lady turned towards him. Lach jabbed at his workbook with a blunt pencil. He got half-way through the sum and then gave up, hacking at what he’d written with a dirty eraser before starting over again. He could feel the sweat working down his back between the shoulder blades. The ceiling fan creaked. The Dragon Lady stopped in front of his desk and peered at the mess he’d made. The moment he dreaded had arrived.

“Can’t you perform one simple calculation?” she snapped.

Lach gazed morosely at the tangle of symbols he’d smudged all over the page. The Dragon Lady huffed, grabbing his pencil from his hand and leant over his desk to cross out the mistakes. He glanced up into a pair of huge sweaty boobs swaying in a white lace bra. They were so close, he could count the pores. Her perfume made his eyes and nose water. Rancid patchouli. Lach grabbed at his nose so as not to sneeze all down the front of Mrs Hajek’s blouse and in the process grazed the teacher’s fat left nipple.

The Dragon Lady jerked upright and gave him a funny look that made him gulp, nose gripped between thumb and forefinger, so now his ears popped as well. He tried to nod at least, like he understood whatever it was, trigonometry, she’d been scribbling in his workbook. There had to be something strange about her, anyhow, he thought, to make them do trigonometry on the last day of school. Maybe she was some kind of sadist, like they showed on the news, who got a thrill letting schoolkids ogle her jugs while she stood over them with a cane or whatever and made them recite the logarithmic tables.

“Lachlan Gibson,” Mrs Hajek proclaimed, “I have my eye on you!”

“Yes miss,” he honked, still clutching his nose.

There was general relief when Crazy Crittendon announced over the PA that they could have the rest of the day after lunch for cricket on the front oval and other sports activities. “Other” meant sitting in the shade and picking your nose while netball girls jumped around with their skirts flapping up. Anyone who wasn’t an outright sissy tried to get onto one of the two cricket teams. Sadleir and Buzik were picked as captains and chose their sides accordingly, one gang against the other, with sundries filling-out the lower order. Crittendon in his big floppy Denis Lilley hat was umpire. He pulled a shiny fifty-cent piece out of his trouser pocket and flipped it in the air. Sadleir called the toss heads and elected to bat. Robbo groaned at the prospect of a long innings standing out in the heat.

“No fear,” Buzik grinned, shinning the ball on his shorts before chucking it to Lach. “This bastard’ll ’ave ’em all carted off on stretchers before the end a the sixth over.”

Lach grinned. He made a lanky slinging motion with his right arm.

“Bodyline the fuckers,” Buzik said, pulling on the keeper’s gloves as they all trudged out to the middle, Crittendon with his knee socks and long sleeves, Sadleir and his chief lieutenant, “Pig Shit” Partlett, with their pads flapping and a pair of battered Duncan Fearnleys.

Lach dug his heel into the dead grass to mark his run-up, making a scar of fine reddish gravel. Buzik crouched down behind the stumps. Robbo and White-as-Wayne stood well back in the slips cordon, hands-on-knees, waiting. Partlett swatted at the weeds with his bat while Sadleir, lazily guarding middle stump, brushed a fly from his nose. The rest of the fielders shuffled forward expectantly as Crittendon, like a scarecrow sagging under its own weight, dropped his left arm and bent towards the batsman. Lach, seam gripped at a cunning angle across his fingers, fixed a beady eye on Sadleir’s stumps and loped into his run-up. The ball flew in a wide arc, bounced, leather crunched into wood. A shout went up. Sadleir and Partlett, unconcerned, jogged down the middle of the pitch, stopped and leant on their bats as scarecrow Crittendon signalled the first boundary of the day.

— Louis Armand

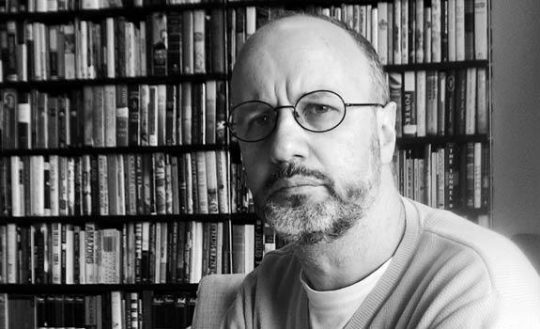

Louis Armand is a Sydney-born writer who has lived in Prague since 1994. He is the author of six novels, including Breakfast at Midnight (2012), described by 3AM magazine’s Richard Marshall as “a perfectmodern noir,” and Cairo, shortlisted for the Guardian newspaper’s 2014 Not-the-Booker Prize (both from Equus, London). His most recent collections of poetry are Indirect Objects (Vagabond, 2014) and Synopticon (with John Kinsella; LPB, 2012). His work has been included in the Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry and Best Australian Poems. His screenplay, Clair Obscur, received honourable mention at the 2009 Alpe Adria Trieste International Film Festival. He directs the Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory in the Philosophy Faculty of Charles University where he also edits the international arts magazine VLAK.

Photo by Fred Filkorn

Photo by Fred Filkorn

(Photo: Robert Reynolds)

(Photo: Robert Reynolds)