TERRIBLE AND TRUE shriek the headlines beneath the gorgeously demonic murder scene. Scene and headline typify the remarkable broadsheet publications from the famous Mexican printshop of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo in the latter years of the 19th century and the early 20th century. Brendan Riley’s translation of Hypothermia by Álvaro Enrigue was just published by Dalkey Archive Press in May, and he has two more books forthcoming. Yet he managed to find time to deliver these gems to NC, marvelous combinations of poetry, cartoon and text, vaguely reminiscent of the tabloids you see at the grocery store checkout counter but not nearly so culturally peripheral in their day. Hyperbolic, true, political, journalistic, satirical, they are an art form unto themselves, a wonderful conjunction of publishing acumen, art and a hungry public.

dg

Some of the most powerful combinations of text and graphics of the early 20th century are to be found in the celebrated broadsheets produced by the Mexico City printing shop of editor, writer, and dramatist Antonio Vanegas Arroyo (1850-1917), with accompanying cartoon illustrations created by the legendary printmaker José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913).

These broadsheets were printed on coarse paper and sold cheaply for widespread public consumption. They were the penny press of the day, frequently compared to our contemporary tabloids. Lurid, melodramatic, and eye-catching (though not tainted by quite the same kink of today’s scandal rags) they were also soundly relevant socially as well as potently satirical, often dispensing indictments of widespread corruption and misery suffered by Mexicans under el Porfiriato, the regime of president-cum-dictator Porfirio Díaz.

The Library of Congress holds a large collection of original examples of these inexpensive gacetas callejeras (street gazettes). The stories they offer are sensational, tragic, and sometimes scandalous. They are typically accompanied by a corrido, the traditional ballad form still used in Mexico to relay and celebrate the popular news of the day. Vanegas Arroyo was one of the best-known publishers of his time, and from 1880 until his death in 1917, he oversaw the production of thousands of these broadsheets. His family carried on the printing business until 2001. One of the main writers for the Vanegas firm was the poet Constacio S. Suárez who may have composed the corridos translated below. Although some of the sheets include the phrase “propiedad de (property of) Antonio Vanegas Arroyo” there is no specific byline or other claim of authorship. Guadalupe Posada’s vivid illustrations often provided appropriate visual accompaniment to these startling episodes. The images presented here are freely available for download from the Library website which also provides extensive archival data for each artifact.

While these historic periodicals have been surveyed and reproduced in a number of different books (Posada’s Broadsheets: Mexican Popular Imagery, 1890-1910 by Patrick Frank; Posada: Illustrator of Chapbooks by Mercurio Casillas; and Posada’s Popular Mexican Prints, edited by Roberto Berdecio and Stanley Appelbaum, to name a few), the texts themselves are typically described or summarized but not always translated in full.

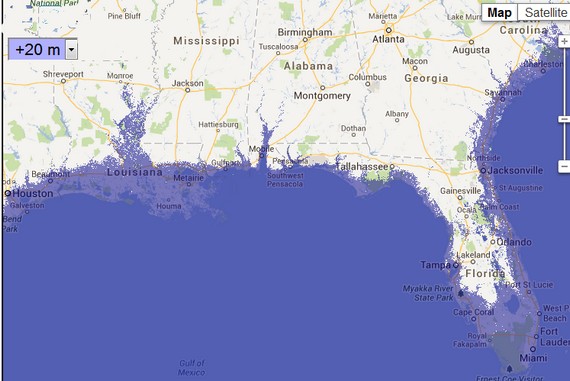

Here are translations from three different broadsheets from the Vanegas Arroyo shop. The first one describes the calamitous flood in Guanajuato, Mexico which occurred on Friday, June 30, 1905. The other two are from 1910, the first year of the Mexican Revolution. One deals specifically with those early days of uprising in Puebla, describing a protracted firefight between the family and allies of the anti-reelectionist leader Aquiles Cerdán and local police and soldiers which resulted in scores of dead and wounded, including police chief Miguel Cabrera who is named in the headline. The third text relates the macabre, cautionary tale of Norberta Reyes, a rebellious, prodigal, only daughter who abandoned her house to follow her lover, then returned home in misery a year later seeking refuge only to murder her doting parents when they tried to move the family to another town to repair the damage her scandalous affair had caused.

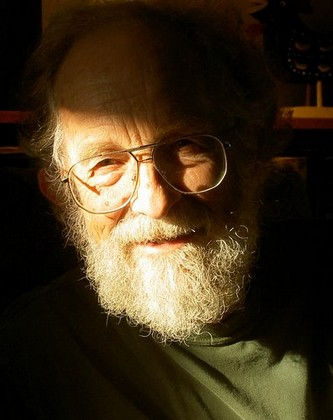

—Brendan Riley

The Guanajuato Flood and Its True Cause

Many years will pass before the horrific catastrophe at Guanajuato, already an unforgettable date in Mexican history, shall be forgotten. The tragic events which took place in that city will, without a doubt, move even the world’s most indifferent and skeptical soul. Such anguish! Such tremendous upheavals!

Only the Great Flood described in the Bible could be compared to this one. Based on accurate calculations, the true cause of this unsettling disaster can be explained as follows: built along the flanks of a canyon, the city of Guanajuato has streets which are narrow, winding, irregular, and not the least bit flat. Most of them form slopes and steep grades, a characteristic which favors flooding. Crossing back and forth through the town is a narrow river which is, in places, sealed over to facilitate traffic. Of course, it is also a well-known fact that the nearby dam has a spillway for those times when the river overflows; this current joins up with the water cascading down from the hills and goes surging through the narrow, covered riverbed. After an hour of the water rushing down through Guanajuato one could hear, above the noise of the pouring rain, a horrendous roar: it was the vaulted coverings over the river which proved inadequate to contain the flood. The floodwaters burst through them, wiping out the city. And after that deluge many people who had saved themselves by climbing up onto their rooftops fell into the water as their houses collapsed underneath them due to the force of the flood. In the wake of this disaster, the few remaining inhabitants face the horrible threat of hunger; as of this writing, groceries are commanding a very inflated price; suffice to say that a tortilla costs now two centavos and a piece of bread, ten.

* * *

Pride of the Republic

For its rich minerals

The city of Guanajuato

Amassed vast capital wealth.

The cradle of liberals

Who always honored their country

And as brave men must, fought

For its progress and greatness

Among the most loyal Nations.

And rightly so, it came to be

That lovely capital city

The first in the country

For its massive splendor.

Buildings without equal

Made from beautiful quarries

Which are the true pride

Of that rich region

And which give the country

Renown among the greatest nations.

Such celebrated riches

Are now practically washed away,

By the terrible flood

Which overflowed the river’s course,

The wall of the great and famous Dam

Torn away from the shore

Joined with the spillway stream

Deluging all the people

The desolation came rushing on

As fast as they could fly.

And all the town of Marfil

Suffered the same, no less

The countless poor, who wander

About with no place to rest.

It’s said that the victims number

More than one thousand dead

In the furious deluge

Which destroyed those cities,

The horror we lament today

Unlike any other of the ages.

* * *

Bloody Events in the City of Puebla – The Death of Police Chief Miguel Cabrera

This past month in the city of Puebla, in the early morning hours of Friday, November 18, quite near the downtown and the Plaza de Armas, various individuals appeared at 5 o’clock in the morning, shouting and firing guns at a house on Santa Clara Street, home of the anti-reelectionist Aquiles Cerdán.

The police arrived to investigate the house, headed by the chief of security Señor Miguel Cabrera who tried to gain entrance, but they were received with gunfire, with Sr. Cabrera and many police officers dying on the spot.

Word was sent to the local barracks and the “Zaragoza” Battalion rushed to their aid, sparking a terrible battle that lasted three hours, resulting in nearly one hundred dead and injured.

In the end, the house was taken by assault and various persons were apprehended. The lifeless body of Sr. Cabrera was recovered from where it lay sprawled on the porch of the house.

The City now finds itself in dismay. All shops are closed, and families are fleeing in search of safe places, for the revolution is terrible and the killing is horrifying.

Santa Clara Street is deserted, its sidewalks stained with blood. Inside the house of Aquiles Cerdán were found some 200 rifles, a large quantity of explosives, attack plans, and many artillery shells and dynamite bombs, several of which were hurled at the federal forces, along with a veritable rain of bullets. A general anti-reelectionist revolution is underway and the general state of panic is very great.

Among those wounded are the First Captain of the Zaragoza Battalion, Don Francisco Aguilar, who, like Colonel Mauro Huerta, fought valiantly against the reelectionists; also wounded are Lieutenant Colonel Abel Licona; Colonel Gaudencio González, a visitor from the headquarters of the State of Puebla; sublieutenant Camilo Ojeda; mounted policeman Wilifrído Cervantes; and countless policemen, soldiers, and passersby.

Among the dead are first counted Police Chief Sr. Miguel Cabrera, and Máximo Cerdán who seems to have directed the revolutionary movement, and who is the brother of the owner of the house on Santa Clara Street; private Angel Durán; Second Sergeant Manuel Sanchez, and two women who were walking along the street at the very moment when the fighting erupted.

Aquiles Cerdán, owner of the house and principal ringleader, was not found and remains at large, a fugitive from justice.

The Government has taken the necessary measures to suppress a growing revolution.

The whole city of Puebla is now deserted: doors are shut, inhabitants hidden in their houses and all business suspended.

Fourteen hours later, an underground vault was discovered in Cerdán’s house. When the hiding place was searched, Aquiles Cerdán appeared, declaring his wish to surrender, but before he could speak another word he was shot dead and carried to the police station on a stretcher.

Four rebels have been brought in from Tlaxcala; their names are Manuel Sánchez, along with Trinidad and Nicolás Sánchez, and Gregorio Florez.

In Orizaba authorities apprehended Victoriano García, José Ventura Sánchez, and Benjamín Rodriguez.

Prisoners brought in from Pachuca were Francisco Noble, a school teacher, Loreto Salinas, Mateo Angeles, and Eligio Ramírez.

Those arrested in San Luis Potosí were: Antonio and Adrián Gutierrez, Luis Martínez, Ernesto and Juan Espinosa and Lucrecio Montejano, a very wealthy man from that city. Others arrested later on were Bacilio and Concepción Regalado, Francisco Padilla, José Rico, José Tamayo, Pedro Torres, José María Espinosa, Francisco Herrera, Antonio Buendía, and Antonio Rangel.

All of these individuals have been confined within the following prisons: Santiago, Cuartel de la Montada, Belem, and the Federal Penitentiary.

Sad Lamentations from the Distraught Citizens of Heroic PUEBLA

Oh Peace, lovely Peace!

Why do you abandon us?

Politics and rumors

Now drive people’s meetings…

And you, that always adorns

Progress so tenaciously,

And the flourishing commerce

You’ve always brought to Puebla

Why do you now fall to chaos

Why do you abandon us

Oh Peace, lovely Peace?

War no matter where you turn!

Great and terrible alarm!

The whole world trembles

If war shows its face,

Brandishing its cruel weapons

Made for spilling blood;

Sowing bitterness,

Filling the heart

and soul with fear,

Now crying out ceaselessly

War everywhere!

Dying! Oh, why die?

Peace is so precious!

The Mother of Progress

Incense of our history

Fragrant and lovely rose

Of the richest garden

The happiest fortune

of life’s pleasure;

Oh venerated Goddess!

Exclaim now proudly:

Dying! Oh, why die?

Oh Peace, lovely Peace!

Do you abandon your children?

But your motherly love

Will never, ever accept that

Because your absence perhaps

Convulses the very future!

Without you, all is broken;

Neither science, nor progress:

Because you thrive on that

Why do you abandon us,

Oh Peace, lovely Peace?

Printed by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo

43 Calle de Santa Teresa, #2

Mexico City, 1910

The True, Terrible, and Shocking Affair of Norberta Reyes, who murdered her parents near the city of Zamora on the 2nd of last month.

In a small town on the outskirts of the city of Zamora, in the State of Michoacán, lived Anselmo Reyes and Pascuala Rosa, whose marriage only produced one child, their daughter Norberta, whom both parents loved with warmth and affection, as much for her being a girl as for being the only fruit of their love.

From a very young age Norberta showed herself to be possessed of a volatile and indomitable spirit; this being fomented by her parents’ indulgence, she grew up to become an insufferable creature for everyone except her mother and father, who in their blind devotion accepted all her caprice as their daughter’s natural grace and charm. And so she reached the age of 16 and not being an unpleasant looking girl, did not take long to meet up with a rascal who won her affections. As she was accustomed to do as she pleased, in spite of her parents’s advice, she reciprocated his desires and, when it was least suspected, disappeared with her lover.

A year and a half had passed without Norberta’s parents knowing anything more about their daughter in spite of their many efforts to discover her whereabouts. One evening she suddenly appeared in their doorway in a truly pathetic state, nearly naked, miserable, filthy, covered with lice, and bearing countless scars on every part of her body.

Upon seeing their daughter in such a lamentable state, her unhappy parents forgot her ingratitude and with a thousand caresses tried to console her sad condition; but this ungrateful daughter, far from being thankful for her parents’s goodness and kindness, each day behaved worse towards them. Norberta could not stop wondering what had become of her despicable seducer. This drove her increasingly out of her mind, and she caused a scandalous uproar day after day in their house, so much so that the neighbors became alarmed, for the which reason Norberta’s elderly parents decided to abandon their town and move to another where they were not known. Harboring hopes that her wicked lover would return in search of her, their depraved daughter was dead set against such a move; but seeing that her parents had made up their mind, she sheltered in her heart the cruelest, most horrible plan.

When the day came that they finally left the town, Norberta carefully concealed on her person a sharp knife and, even pretending to be happy, she set out with her elderly and beloved parents who could not imagine the sad fate their daughter had in store for them.

To reach the town they were headed for, they were obliged to pass through a very solitary spot, and there, in order to rest, they stopped and prepared their meager lunch. After eating, overcome with fatigue, the old couple lay down on the grass. When the vile Norberta saw them asleep, she took out the murderous knife and leaping first upon her old father, struck him a terrible blow to the neck which nearly severed his head from his body.

The noise of the bloody drama awoke the old woman; but before she could rise from the ground her wicked daughter hurled herself at her, plunging the knife repeatedly into different parts of her mother’s body until most of her innards were hanging out, leaving the unfortunate woman completely cut to pieces.

Her horrible crime now committed, Norberta set out on the road back towards her town; but without realizing it, she lost her way. After walking all day long, she found herself by nightfall in a dry, desolate place near a deep ravine.

There she paused, because by now her fatigue prevented her from walking farther. Around eleven o’clock at night she heard a chorus of hellish sounds that seemed to rise out from the depths of the ravine, and a few moments later she saw emerge from the same, two enormous black dogs baring their teeth and jaws with a frightful sound. They leapt upon the wretched Norberta, tearing her furiously, dragging her down into the ravine, and hurling her to the bottom. There she finally died five days later, tormented by hunger, thirst, and the terrible sharp pains from the bite wounds, by now festering with maggots.

The same day of this terrible occurrence, the police discovered the corpses of the old couple, who were then buried in the cemetery, unlike the body of their heinous daughter. Although her body was spotted at the bottom of the ravine it could not be removed from there because when they tried to, the body was lost to sight and was only glimpsed again the following day.

This extraordinary event serves to show parents the obligation they bear to not indulge their children, and that from their earliest infancy they must always curb their bad inclinations.

* * * * * * * * * *

I hearkened to the seductions

of a depraved and vile man

Who at last abandoned me

Making me sadder than before.

His wicked wounded heart

Did mine, in turn, pervert

So that now I do suffer

The very torments of Hell,

Which shall be punishment eternal

For my horrible sin and transgression.

Like a wild, furious beast

I killed my beloved parents,

Tearing out their life

With strange, unspeakable cruelty.

Forgive me, dear Mother!

Forgive me, worshipful Father!

Now my punishment has arrived,

If only I might have died alone

In that desert a thousand times

Before I’d murdered them!

Last month I committed

an atrocious crime

I delivered death unto them both

With horrible cruelty.

But the punishment decreed by God

Came down like lightning

And my body was flung

From atop a ravine into the depths

And there lay broken and lifeless

To be by worms devoured.

Blinded by love and affection

My parents indulged me,

Leading to my disgrace,

They saw their mistake too late.

And for not being reprimanded,

They both became victims

Of my too-kind upbringing,

And twisted inclinations.

And this love, badly entertained,

Has now wrought my perdition.

Printed at 29 Calle de la Penintenciaría #2, Mexico City

—Translated by Brendan Riley

—————————–

Brendan Riley has worked for many years as a teacher and translator. He holds degrees in English from Santa Clara University and Rutgers University. In addition to being an ATA Certified Translator of Spanish to English, Riley has also earned certificates in Translation Studies and Applied Literary Translation from U.C. Berkeley and the University of Illinois, respectively. His translation of Eloy Tizón’s story “The Mercury in the Thermometers” was included in Best European Fiction 2013. Other translations in print include Massacre of the Dreamers by Juan Velasco, and Hypothermia by Álvaro Enrigue. Forthcoming translations include Caterva by Juan Filloy, and The Great Latin American Novel by Carlos Fuentes.