Rashmi Vaish

Rashmi Vaish

Introduction

Fictional reliability as a device of point of view is one of the most complex elements of craft. It relates to the ways in which an author causes the narrators or characters to interact with the fictional world and each other to present different perspectives or points of view to manipulate the reader’s experience of and response to the story.

Point of view in literature, according to David Jauss in Alone With All That Could Happen,

…refers to three not necessarily related things: the narrator’s person (first, second, or third), the narrative techniques he employs (omniscience, stream of consciousness, and so forth), and the locus of perception (the character whose perspective is presented, whether or not that character is narrating). Since there is no necessary connection between person, technique, and locus of perception, discussions of point of view in fiction almost inevitably read like relay races in which one definition passes off the baton to the next…(25)

The last element of point of view that Jauss speaks of, the locus of perception, is where I would pass the baton to fictional reliability. For this thesis I explore three novels with multiple points of view and discuss how the point of view complexes relate to reliability within each of them: Ironweed by William Kennedy, Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler, and The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner.

First, a brief discussion of reliability. Wayne C. Booth in his book The Rhetoric of Fiction talks of reliability as a point of view narration concept relating to authorial distance:

In any reading experience, there is an implied dialogue among author, narrator, the other characters, and the reader. Each of the four can range, in relation to each of the others, from identification to complete opposition, on any axis of value, moral, intellectual, aesthetic, and even physical. (155)

For practical criticism probably the most important of these kinds of distance is that between the fallible or unreliable narrator and the implied author who carries the reader with him in judging the narrator. If the reason for discussing point of view is to find how it relates to literary effects, then surely the moral and intellectual qualities of the narrator are more important to our judgment than whether he is referred to as “I” or “he,” or whether he is privileged or limited. If he is discovered to be untrustworthy, then the total effect of the work he relays to us is transformed. (158)

He then goes on to define reliable and unreliable narrators:

For lack of better terms, I have called a narrator reliable when he speaks or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author’s norms), unreliable when he does not. (Booth 158)

Depending on the text, the narrators could be wholly reliable, wholly unreliable, or range somewhere along the spectrum—parts of their experience feel true and are in keeping with the novel world; others, though told with conviction, the reader knows are false. The reader knows this because the other characters in the narrative tell us so; the author tells us by depicting the world in opposition to the character. The reader sees clearly that the character is not perceiving the novel world accurately.

While the first-person mode of narration is what initially comes to mind when discussing reliability or unreliability as a device of point of view, “the most important unacknowledged narrators in modern fiction are the third-person ‘centers of consciousness’ through whom authors have filtered their narratives.” (Booth 153) These narrators provide a range of depictions of characters’ minds, from delving deep into the “complex mental experience” to the “sense-bound ‘camera eyes’” experience. Any kind of narration along this spectrum when used in conjunction with other craft devices leads to reliability or unreliability.

In novels with single points of view, where there is one narrating consciousness through whose eyes the reader must see the novel world, first-person or third, there is a pressure on the narrating consciousness to provide the bulk of the significant detail of the story. We get back story, history and setting through devices like memory, perception and interior monologue, and other characters’ opinions of the narrator through direct dialogue in present action or memory scene. In novels with multiple points of view, however, this pressure is alleviated. We get a variety of views on the novel world, each perspective coloring the same events in different hues. One perspective is set up against the other and so we as readers discover for ourselves which narration holds the most reliability or unreliability.

Ironweed

First published in 1983, Ironweed by William Kennedy won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1984. The book is the third in Kennedy’s Albany series of novels, though stands alone as a single work. Francis Phelan, a former major league baseball player, is a vagrant drunk who has returned to his hometown of Albany after 22 years. He fled home after dropping his infant son Gerald and killing him. Prior to that he had run away for a while after killing a man during a transit strike and was on the road extensively during his baseball career. The novel, which takes place over two days and nights, opens with Francis in St Agnes Cemetery, where his family and relatives are buried. He and another bum friend of two weeks, Rudy, have picked up a job digging graves because Francis needs to work off some legal fees. In the cemetery, Gerald’s ghost imposes a silent act of will on Francis indicating that he needs to “perform his final acts of expiation for abandoning the family.” (19)

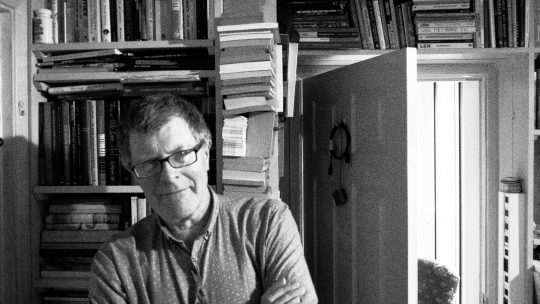

William Kennedy

William Kennedy

Francis isn’t consciously aware of this; in the cemetery he sees no ghosts, hears no voices. It is Halloween and it is only when Francis leaves the cemetery that he begins to see ghosts of the people he has killed. During the course of the night he meets up with Helen Archer, a hobo with whom he has had a relationship for nine years. Helen, who used to be a musician from a good family and is now dying of a tumor, is the other point of view consciousness of the novel. That night Helen is robbed of her purse.

The following day Francis gets a job with a man who hauls junk and while on their rounds he enters his old neighborhood, which makes him remember his own home, his neighbors, parts of his childhood and young adult years. He decides to buy a turkey with his day’s earnings and visit his family, with whom he ends up spending the evening. While there, he finally faces his wife, Annie, who welcomes him into their home. She is surprised to see him but bears no acrimony towards him. He apologizes to her, telling her that he still loves them but expects nothing. He meets his grandson, his son and daughter, and Annie cooks the turkey for the evening meal, for which he stays. He bathes, wears a clean suit that used to belong to him, and hands his present rags over to be discarded. Annie acknowledges that his returning, visiting Gerald’s grave, and coming to see her is significant. She asks if he wants to stay, he refuses, but she leaves the possibility open. The family has dinner together.

Later, he goes to find Helen, who in the meantime has checked into a hotel and is preparing to die. He leaves some money for her at the desk and meets up with Rudy. Soon after, however, the hobo jungle is raided, and Rudy is seriously injured in the violence. Francis takes him to the hospital, where Rudy dies. He returns to the hotel and finds Helen dead. He gets back on a train out of Albany to flee the police once again, but the ghost of Strawberry Bill tells him the police are not looking for him and that the house, the attic with the cot he saw earlier, is the best place for him to be. He projects into the future, thinks about possibly even moving into his grandson’s room when the time is right. In the end he finds peace in Anneie’s forgiveness. His spiritual burden is lifted, his deeds over the two days a fulfilling of the expiation that Gerald’s ghost imposed on him.

The Author as God Voice/Omniscient Narrator

While the bulk of the novel occurs in Francis Phelan’s point of view, with Helen Archer a secondary point of view character, the first chapter of the novel has a distinctly different perspective. This voice, the authorial voice or reliable omniscient third person narrator, sets up Francis’ world in context to the Catholic afterlife with the literal introduction of the dead speaking and interacting with the world right in the beginning of the novel—his mother twitches in her grave and his father lights his pipe (1). The author gives the reader a great deal of mobility in this section in terms of distance, taking the reader close into Francis’ thoughts and far out into the spirit world that Francis is not yet aware of. The modes of interiority are used not only for Francis, but for the ghosts around Francis in the cemetery as well. The ghosts in this section don’t just speak amongst themselves; in a presaging of what is to come in the novel, they speak to Francis as well, like Louis (Daddy Big) Dugan, who tells Francis that his son Billy “saved my life.” (5) Only, at this point Francis doesn’t hear or see any ghosts yet.

The dramatic action begins with Francis riding in a truck through the cemetery in Albany where his family is buried. The narrator/observer moves with Francis through the graveyard, giving us back story and character setup for Francis as well:

Francis knew how to drink. He drank all the time and he did not vomit. He drank anything that contained alcohol, anything, and he could always walk, and he could talk as well as any man alive about what was on his mind…He’d stopped drinking because he’d run out of money, and that coincided with Helen not feeling all that terrific and Francis wanting to take care of her. Also he had wanted to be sober when he went to court for registering twenty-one times to vote. (6)

The most important piece of setup in this chapter, the event that sets the rest of the novel in motion, comes when Francis goes to his infant son Gerald’s grave. The authorial voice indicates that this is an important moment by describing Francis’ dead father Michael signaling to “his neighbors that an act of regeneration seemed to be in process” (16).

A brief shift into Rudy’s mind also occurs before Francis arrives at Gerald’s grave, giving us multiple perspectives on the significance of the action unfolding:

Rudy followed his pal at a respectful distance, aware that some event of moment was taking place. Hangdog, he observed. (17)

At this point the narration speaks from Gerald’s perspective as ghost, though Francis remains unaware:

Gerald, through an act of silent will, imposed on his father the pressing obligation to perform his final acts of expiation for the family… You will not know what these acts are until you perform them… when these final acts are complete, you will stop trying to die because of me. (19)

The unadorned declarative text that lays out his immediate future path grounds his character in the novel world. The authorial voice gives the reader the guidepost to understanding Francis and his actions to come. This chapter functions as the closest example of a reliable, omniscient narrator who is the only one in the novel world fully aware of everything surrounding Francis, including the afterlife and the task that Francis must perform, which he is unaware of, but which the reader knows.

Francis Phelan

Throughout the action of the novel we get to go deep into Francis’ mind. He is a man literally haunted by ghosts. Surely this is an unreliable mind that is hearing and perceiving voices and judgments from beyond. However, it quickly becomes evident that the invention of the ghosts is a tool to show Francis interacting with his past; we all talk to the dead in some form or another, and for Francis this is a way for him to come to a reckoning with his life and choices. The ghosts are a vital part of the subterranean dramatic action of the novel, each one speaking and eliciting responses in Francis that give us a clearer picture of his life and character and the way he interacts with his own truths. While he does not see ghosts in the cemetery, he does see them outside it on the streets of Albany.

Francis’ reliability comes into play in the first chapter itself, during the omniscient narrator’s point of view. His recall of events is detailed and unembellished. When he is at Gerald’s grave, for instance, he remembers with particular clarity what happened the day he dropped his son all those years ago. The dramatic action so far has Francis walking through the cemetery, reading names on graves. Each name prompts memory and reflection conveyed through a close narrative voice describing what he sees, Francis’ character thought, indirect and direct interior monologue. Francis aims straight for Gerald’s grave, even though he has never seen it before. Once there, Francis starts crying. His tears falling onto his shoes and his action of clutching at the grass triggers his memory of Gerald’s wet diaper and the way he’d clutched it years ago:

Twenty-two years gone, and Francis could now, in panoramic memory, see, hear, and feel every detail of that day… His memory had begun returning forgotten images when it equated Arthur T. Grogan and Strawberry Bill, but now memory was as vivid as eyesight. (18)

This is the first point in the novel where language overlay gives the reader a clear indication that Francis himself is a reliable consciousness—his memory is “as vivid as eyesight.” Francis then unburdens to his dead son:

“I remember everything,” Francis told Gerald in the grave. “It’s the first time I tried to think of those things since you died. I had four beers after work that day. It wasn’t because I was drunk that I dropped you. Four beers, and I didn’t finish the fourth.” (18-19)

The technique used to draw out Francis’ memories and associated feelings of guilt or justification in the novel is fairly consistent throughout: the dramatic action has him traveling the streets of Albany; street names and objects he encounters trigger passages of memory, back story, narration through dialogue with other characters, and the appearance of ghosts of men he has killed.

When he is with Rudy going by Erie Street (24), for instance, they are in scene passing “old carbarns at Erie Street…but it looks a lot like it looked in ’16.” The narration then immediately dips further back to ’01, to the memory of a strike that turned violent. The passage moves into flashback, describing the scene during which Francis “brained the scab working as the trolley conductor” (25) and subsequently fled on a train winding up in Dayton, Ohio. The narration then reveals the scab’s name (Harold Allen), the fact that he was the first man Francis ever killed, and in the same long sentence shows him sitting across the aisle in the bus Francis is traveling in. Francis gets into a dialogue with Allen’s ghost and defends his reason for having killed him. While he confesses to the ghost, he doesn’t tell Rudy that he killed the scab (27). Instead he relates to Rudy how he tried to save a man who was running from the police but couldn’t. The narration of that story triggers the appearance of that man’s ghost as well. Here, too, Francis’ reliability, though he lied to Rudy, is underscored by the close narrator telling the reader of the lessons that man left with Francis (“life is full of caprice and missed connections…a proffered hand in a moment of need is a beautiful thing”), all of which Francis “knew well enough.” (28) While he lies on the outside so as to not incriminate himself, he fully admits to himself the consequences and implications of what he did.

Francis’s reliability as a character consciousness doesn’t just come from him seeing his own life for what it is; he also sees the world and the people he comes across for who they are. In one long sequence, he helps cover up a vagrant woman named Sandra. When Rudy tells him she’s been a bum all her life, he tells Rudy that “nobody’s a bum all their life, she hada been somethin’ once.”(31) Later in a saloon, when the barman Oscar sings, Francis in a moment of insight sees Oscar’s life for what it has been which “raised in Francis a compulsion to confess his every transgression…It wasn’t Gerald who did me. It wasn’t drink and it wasn’t baseball and it wasn’t really Mama.” (50) The passage here begins with Francis’s emotion reflected in the narrator’s voice and dips immediately into direct interior monologue where he confronts his own truth.

Even towards the end of the novel, the reliability of Francis’ knowledge of himself and the world and his willingness to confront what he finds remains. A scene begins again with Francis traveling north on Erie Boulevard and he is reminded of a labor leader, Emmet Daugherty, whose son wrote a play about the incident in which Harold Allen was killed. The play featured Francis and the killing. The novel’s narration dips into the back story of Emmet, moves through Francis’ memory of the story he has told himself about that fateful night and why he killed Allen. But then he sees

…the strike as simply the insanity of the Irish, poor against poor, a race, a class divided against itself. He saw Harold Allen trying to survive the day and the night at a moment when the frenzied mob had turned against him, just as Francis himself had often had to survive hostility in his flight through strange cities, just as he had always had to survive his own worst instincts. For Francis knew now that he was at war with himself…and if he was ever to survive, it would be with the help not of any socialistic god but with a clear head and a steady eye for the truth; for the guilt he felt was not worth the dying… The trick was to live…and show them all what a man can do to set things right, once he sets his mind to it. (207)

The narration is his thoughts reflected partly in a narrative voice close to him, partly in his own voice, both pointing to his willingness and ability to face the truth about himself and about his world.

Helen Archer

Helen, on the other hand, has a far more tenuous hold on the world she inhabits. While Francis is the main, reliable character consciousness or point of view through which we experience the novel world, we do get to know Helen in the close third point of view as well, only she is unreliable. We first get a glimpse into her mind during Francis, Helen, and Rudy’s visit to The Gilded Cage, when Francis asks her to sing a song. During the scene, the piano man plays the tune she asks for and as she gets up and walks onto the stage, the dramatic action slips into direct interior monologue towards the end of the sentence, then immediately moves into a close narration of her memory as filtered by her consciousness:

…Helen smiled and stood and walked to the stage with an aplomb and grace befitting her reentry into the world of music, the world she should never have left, oh why ever did you leave it, Helen? She climbed the three steps to the platform, drawn upward by familiar chords that now seemed to her to have always evoked joy, chords not from this one song but from an era of songs, thirty, forty years of songs that celebrated the splendors of love, and loyalty, and friendship, and family, and country, and the natural world. Frivolous Sal was a wild sort of devil, but wasn’t she dead on the level too? Mary was a great pal, heaven-sent on Christmas morning, and love lingers on for her. The new-mown hay, the silvery moon, the home fires burning, these were the sanctuaries of Helen’s spirit, songs whose like she had sung from her earliest days…they spoke to her, not abstractly of the aesthetic peaks of the art she had once hoped to master, but directly, simply, about the everyday currency of the heart and soul. The pale moon will shine on the twining of our hearts. My heart is stolen, lover dear, so please don’t let us part. (54)

The language in this passage signals a significant shift from Francis’ point of view. Where music moves him to question Oscar the barman’s suffering and so confront his own, for Helen music inspires images of warmth, love lost and gained, hope. Where the syntax in Francis’ perspective tends towards concrete detail and declarative statements, in Helen’s perspective we get more abstraction (“love,” “loyalty,” “friendship,” “natural world”), poetic imagery, fragmented thoughts that jump from one sentence to the next. Reliability for Helen in this case is a question of whether she sees the world for what it is or for what she wants to see in it.

Another marker of Helen’s unreliability comes when the dialogue she has during the narration in her consciousness is presented without quote marks:

By god that was great, Francis says. You’re better’n anybody.

Helen, says Oscar, that was first rate.

Oh thank you all, says Helen, thank you all so very kindly. (57)

We have only seen this in the text so far when Francis talks to his ghosts, the one element of unreliability for Francis. Helen, it indicates, doesn’t always perceive the people around her to be real or the world in which she operates tangible.

In Chapter V we get a far more detailed look into Helen’s consciousness. The filter once again is incredibly hazy. The chapter opens with Helen in direct interior monologue. From there the narration dips into back story, flashback memory and Helen’s current, fragmented thoughts, the distance moving from all the way inside her mind and her voice to just outside her. Here, too, the syntax breaks up, in fact becomes verse-like with thoughts ending in commas before moving onto the next line in poetic form, especially when she recalls the death of her father:

A visitor, said Mrs. Carmichael, your uncle Andrew: who told Helen her father was ill,

And on the train up from Poughkeepsie changed that to dead,

And in the carriage going up State Street hill from the Albany depot added that the man had,

Incredibly,

Thrown himself off the Hawk Street viaduct. (118)

Like Francis has a kernel of unreliability in him, Helen has some reliability as well: she recognizes when she is going to die and makes sure she gets off the street. In this passage, the dramatic action is that she swoons in a record store. The dialogue with the fellow customer and clerk is punctuated with quotation marks—she sees the reality of what is going on. The syntax is now firm and declarative.

“Rest a minute,” the girl said. “Get your bearings first. Would you like a doctor?”

“No, no thank you. I know what it is. I’ll be all right in a minute or two.”

But she knew now that she would have to get the room and get it immediately. She did not want to collapse crossing the street. She needed a place of her own, warm and dry, and with her belongings near her. (132)

Later in the room Helen slips back into her reverie state when she is finally alone with her thoughts and death upon her, the narration ending in similar poetic syntax as when she recalled her father earlier:

And after he goes away from the door she lets go of the brass and thinks of Beethoven, Ode to Joy,

And hears the joyous multitudes advancing,

Dah dah-dah,

Dah dah-de-dah-dah,

And feels her legs turning to feathers and sees that her head is floating down to meet them as her body bends under the weight of so much joy,

Sees it floating ever so slowly

As the white bird glides over the water until it comes to rest

On the Japanese kimono

That has fallen so quietly,

So Softly,

Onto the grass where the moonlight grows. (139)

Francis and Helen are two opposites in the world of this novel. The reader gets to go deep into both of their minds to discover how each of them perceives themselves and the world they live in. Where Francis is a realist, Helen is not. Kennedy links up two vastly differing perspectives, the one heart of Helen and the one mind of Francis, and places them both in a dull, dreary, harsh world. The reader is placed close to both points of view; both elicit sympathy, even sorrow.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant is a 1982 novel by Anne Tyler told in the close third person points of view of Pearl Tull, an abusive, perfectionist, single mother; her oldest son Cody; middle child Ezra; and the youngest, Jenny. The novel opens with Pearl as a dying, 85-year-old woman. Ezra lives with her and is taking care of her. As she is dying, she falls into memory and flashback, during which we learn about a few key events that have shaped the family: an archery accident in which Cody misfires an arrow after grappling with Ezra and shoots it into Pearl wounding her, after which she has a bad reaction to Penicillin and nearly dies; husband and father Beck’s courtship of Pearl, their marriage, and his abrupt departure from the family; how Pearl kept a tight lid on her emotions, finding herself unable to cry in front of her children; how she found a job to support herself and the children; and despite being “an angry sort of mother,” (19) how she kept everyone sheltered, clothed, and fed.

Anne Tyler

Anne Tyler

The novel intersperses the three siblings’ points of view and in subsequent chapters takes their stories through their lives to the time of Pearl’s death. Cody, jealous and envious of Ezra, grows to become an efficiency expert and steals away Ezra’s only love interest Ruth. Ezra starts working at a neighborhood restaurant when he reaches his teens and after a short stint in the military, returns home and takes over the running of the restaurant, ultimately inheriting it from the owner, Mrs. Scarlatti, after she dies. Jenny single-mindedly pursues a medical career in which she is successful as a pediatrician, but like her mother proves unsuccessful in marriage till her third try. All three siblings remember their mother as not just angry but abusive as well. Through the entire course of the novel, it is Ezra’s wish that the whole family eat a full meal at his restaurant, but every time the family gets together, there’s an argument and the meal is left incomplete. At the end, after Pearl has died, Beck turns up at the funeral—Pearl tells Ezra to invite him. Once again, the dinner is interrupted but after one final scene between Beck and Cody, the entire family heads back to the restaurant and finally sits down together to finish their meal.

The modes of telling in the story include memory in flashbacks and interiority using direct and indirect interior monologue with a close third person narrating voice that moves in and out of each one’s mind and never strays beyond just outside the mind when in that perspective.

Pearl Tull

Pearl, the matriarch, is perhaps the most complicated of all the Tulls depicted in the book. As a center of consciousness, she displays equal measures of engaging and refusing to engage with her world. Pearl’s perspective of her own life and her children’s lives and the way she engages with them colors everything in the world of this novel.

We meet Pearl as she is dying, when she wants to tell Ezra that he “should have got an extra mother.” (3) From there the text moves into flashback about how she met and married Beck and how he left her and the children, the foundation back story of the family and the novel. In the memory of when he tells her he’s leaving we get the first glimpse of Pearl as someone who perhaps doesn’t engage fully with the world:

Pearl felt she was sinking in at the center, like someone given a stomach punch. Yet part of her experienced an alert form of interest, as if this were happening in a story. (9)

She takes “infinite care” (10) to not tell the children that their father has left and even when her old friend Emmaline spends the night, she “caught herself” (11) before she told her the truth. This, of course, is because she truly believes that they were a happy family—a fact that Beck denies towards the end of the novel. Much of these thoughts are delivered through indirect interior monologue like here:

…outsiders would go on believing the Tulls were a happy family. Which they were, in fact. Oh, they’d always been so happy! They’d depended only on each other, because of moving around so much. It had made them very close. He’d be back. (11)

The indirect monologue in memory continues to a point where it is revealed that she really did believe that her children didn’t realize that their father was gone, pointing directly to her unreliability as a point of view perspective:

She was amazed, in fact, that she’d managed to keep it from them for so long. Had they always been this easy to fool? (14)

She rehearses in her mind how she would break the news to them (14) but doesn’t. And when she finally does just as Cody is leaving for college, the scene, still in flashback, reveals her children to be impervious to her words—it’s a piece of information that holds importance only to Pearl, the children have long known:

“There’s something I want to explain about your father,” Pearl told them.

“Choose the cafeteria,” Ezra said.

“Children?”

“The cafeteria,” they said.

And all three gazed at her coolly, out of gray, unblinking, level eyes exactly like her own. (31)

While much of the first chapter in Pearl’s point of view is in flashback, the dramatic action is Pearl slipping in and out of her haze of memory. While most of her interiority during the memories shows her as being in denial, present action dying Pearl does begin to confront some truth about her life, even though she still justifies it:

Oh, she’d been an angry sort of mother. She’d been continually on edge; she’d felt too burdened, too much alone. And after Beck left, she’d been so preoccupied with paying the rent and juggling the budget and keeping those great, clod-footed children in new shoes. (19)

A brief moment of reliability for Pearl does come when she evaluates her children’s personalities. She is still in memory, a time when she dreamt of the family during a trip to the beach and felt like that would be heaven. When she tells Cody about her vision of heaven being that trip to the beach, he rejects it. Once again, however, the reliability is fleeting:

Something was wrong with him. Something was wrong with all of her children. They were so frustrating—attractive, likable people, the three of them, but closed off from her in some perverse way that she couldn’t quite put her finger on. And she sensed a kind of trademark flaw in each of their lives. Cody was prone to unreasonable rages; Jenny was so flippant; Ezra hadn’t really lived up to his potential…She wondered if her children blamed her for something. Sitting close at family gatherings (with the spouses and offspring slightly apart, nonmembers forever), they tended to recall only poverty and loneliness—toys she couldn’t afford for them, parties where they weren’t invited. Cody, in particular, referred continually to Pearl’s short temper, displaying it against a background of stunned, childish faces so sad and bewildered that Pearl herself hardly recognized them. Honestly, she thought, wasn’t there some statute of limitations here? When was he going to absolve her? (22)

Again, she sees that there are flaws, but doesn’t quite understand where they are coming from. The language is questioning, uncertain, the syntax often meandering into side observations and thoughts with parentheses. The mind thinking this is not grounded.

Later in the novel, however, she does display one complete moment of clarity. The dramatic action is Ezra and Pearl at Cody’s farm, taking care of the house.

She looks down and sees, with a pang, that his lovely fair hair is thinning on the back of his head. He is thirty-seven years old, will be thirty-eight in December. He will probably never marry. He will never do anything but run that peculiar restaurant of his, with its hodge-podge of food, its unskilled waitresses, its foreign cooks with questionable papers. You could say, in a way, that Ezra has suffered a tragedy, although it’s a very small tragedy in the eyes of the world. (178)

For once the syntax is straightforward. The sentences are short, declarative, and do not meander.

Cody Tull

Of all the siblings, Cody is the most volatile, the most unforgiving, and in being so is most like his mother. While we get Pearl’s assessment of him (22), it’s not till the reader is taken into his point of view complex that we begin to see the kernels of truth in Pearl’s knowledge. As the oldest, his experience of the family’s history among the siblings is the longest and most well-formed. He has more clear memory and has had more time to build resentments. Cody’s perspective is also presented via memory and interiority, only in Cody’s case the indirect interior monologue is less meandering than Pearl’s. There is also more scene and dramatic action in Cody’s narration than in Pearl’s.

The action of Cody’s narration begins in flashback scene with the fateful archery incident, which so far, we have only seen reference to in Pearl’s memory. It is during this scene that we get the first clue of Cody’s resentment towards Ezra:

Ezra was her favorite, her pet. The entire family knew it. (37)

And later when the arrow pierces Pearl:

“See what you’ve gone and done?”

“Did I do that?”

“Gone and done it to me again,” Cody said… (39)

As the flashback action continues, there is more scene and dialogue in which Cody displays his disdain for Ezra and the things he does to torment Ezra (48-49). His jealousy towards Ezra begins to be cemented in another scene in which he learns that Ezra went to the house of a girl he is interested in. He shuts Ezra out of the house when they return home. (56-57) Cody never grows out of his jealousy. He constantly perceives Ezra as stealing the attentions of his girlfriends, though does admit (correctly so) that Ezra was “honestly unaware of the effect he had on women. No one could accuse him of stealing them deliberately. But that made it all the worse, in a way.” (131) The one time a woman is not captivated by Ezra, Cody loses interest in her (132).

And finally, when the time comes and Ezra does indeed notice a woman, Ruth, Cody mercilessly pursues her and steals her away, and once he does, he keeps her away from Ezra at all times, still convinced that Ezra will take her away.

On a sliding scale of unreliability, Cody isn’t entirely unreliable. He has some moments of genuine feeling and does take concrete action to be helpful. One instance where a genuine feeling comes up is when he is spending time with a girl called Lorena. During the course of the dialogue Cody pokes fun at his mother, describing her disparagingly (45). As soon as he finishes, though, the narration moves inside him:

He was smiling at Lorena as he spoke, but inside he felt a sudden pang. He pictured his mother at the register, with that anxious line like a strand of hair or a faint, fragile dressmaker’s seam running across her forehead. (45-46)

Later in a scene in which Pearl is “on one of her rampages” and has ransacked Jenny’s room, he jumps into action and helps straighten things out for Jenny (50). He also has a moment of realization when he is feeling jealous about his friends’ families. The dramatic narrative has Cody walking back home, his thoughts conveyed through indirect interior monologue:

And his father: he had uprooted the family continually, tearing them away as soon as they were settled and plunking them someplace new. But where was he now that Cody wanted to be uprooted, now that he was saddled with a reputation and desperate to leave and start over? His father had ruined their lives, Cody thought—first in one way and then in another. He thought of tracking him down and arriving on his doorstep: ‘I’m in trouble; it’s all your fault. I’ve got a bad name, I need to leave town, you’ll have to take me in.’ But that would only be another unknown city, another new school to walk into alone. And there, too, probably, his grades would begin to slip and the neighbors would complain and the teachers would start to suspect him first when any little thing went wrong; and then Ezra would follow shortly in his dogged, earnest, devoted way and everybody would say to Cody, “Why can’t you be more like your brother?” (59)

Cody, though weighing more on the unreliable side of the scale, is also arguably the most important of the siblings when it comes to narrating consciousnesses in the novel (three chapters are devoted to Cody’s perspective, two each to Pearl, Jenny and Ezra and one to Luke, Cody’s son). For all the bitterness that he has carried through the novel, he is the character who has undergone the most significant change. Towards the end, it is Cody who confronts Beck at the funeral, and while he accuses him of leaving them “in her clutches,” (299) he doesn’t combust. As the scene unfolds, Beck gets to have his say in the dialogue, explains himself, and Cody listens. At the end, it is Cody who leads Beck back to the family to finish their dinner. (303)

Ezra Tull

Clearly Pearl’s favorite and Cody’s nemesis (as Cody sees him), Ezra tends to lean more towards the reliability end of the scale. He is able to see (for the most part) people around him for who they are, and his life for what it is. Ezra’s point of view complex begins in chapter 4, when Ezra is twenty-five years old. Mrs. Scarlatti, the restaurant owner who took him under her wing, is critically ill and in the hospital. Ezra’s point of view complex is much like Cody’s, but without the language of negative emotion. The narration is dramatic action coupled with interiority in indirect interior monologue. We see Ezra’s perspective on his and Mrs. Scarlatti’s life in reflection as he is sitting by her side:

…Ezra himself: well, he had not actually been through anything yet. He was twenty-five years old and still without wife or children, still living at home with his mother. What he and Mrs. Scarlatti had survived, it appeared, was year after year of standing still. Her life that had slid off somewhere in the past, his that kept delaying its arrival—they’d combined, they held each other up in empty space. Ezra was grateful to Mrs. Scarlatti for rescuing him from an aimless, careerless existence and teaching him all she knew; but more than that, for the fact that she depended on him. If not for her, whom would he have? His brother and sister were out in the world; he loved his mother dearly but there was something overemotional about her that kept him eternally wary. (114)

His reliability establishes itself in the peacefully reflective tone, with an even and measured syntax. The sentence lengths vary, but are not jarring, the ideas not fragmented like Pearl or harsh like Cody’s.

The next point of view for Ezra occurs in chapter 9 when he is now forty-six years old. He continues to be aware of the world around him, his perspective still calm and peaceful. He notices a lump on his thigh one morning and in considering cancer as a possible cause his thoughts, in direct interior monologue, turn to acceptance of death. He dismisses it soon after:

He shook that away, of course. He was forty-six years old, a calm and sensible man, and later he would make an appointment with Dr. Vincent. … It wasn’t that he really wanted to die. Naturally not. He was only giving in to a passing mood… (257)

The interior monologue continues with Ezra assessing his mother’s health and blindness, his siblings’ distance and inability to help, and his own business’s floundering. And through the remainder of his narration, he helps Pearl uncover moments from her past by reading her childhood diary entries back to her. Ezra’s narrating consciousness is steadfast and unwavering.

Jenny Tull

The youngest of the family and perhaps the most tortured by Pearl, Jenny spends most of the story on the unreliable side of the spectrum. She does, however, see the truth about Pearl:

Jenny knew that, in reality, her mother was a dangerous person—hot breathed and full of rage and unpredictable. The dry, straw texture of her lashes could seem the result of some conflagration, and her pale hair could crackle electrically from its bun and her eyes could get small as hatpins. Which of her children had not felt her stinging slap, with the claw-encased pearl in her engagement ring that could bloody a lip at one flick? Jenny had seen her hurl Cody down a flight of stairs. She’d seen Ezra ducking, elbows raised, warding off an attack. She herself, more than once, had been slammed against a wall, been called “serpent,” “cockroach,” “hideous little sniveling guttersnipe.” (70)

The language is far richer in imagery than Cody or Ezra’s. And the sting of rebuke heavy in the recall of Pearl’s behavior, the truth of which appears valid. Part of Jenny’s unreliability comes from her impulsiveness. Though she has a set plan to become a pediatrician (82) right from college—a goal she accomplishes later in life—her marriage choices are impulsive. Another part of her unreliability arguably comes from her changing perception of home. At first she stays away from home during college breaks because she feels “dampened” (83) by the house. But when her marriage breaks down, she returns and “finds the house restful suddenly.” (101) In that scene her thoughts move to her father leaving and she believes that her father leaving “was only a fluke—some misunderstanding still not cleared up.” And instead of staying away from Pearl, she tends to lean on her, allowing her to make her tea.

Later, when Jenny marries the man who was deserted by his wife, she is unable, despite her profession to see that his son, Slevin, is having trouble coping. The scenes and dialogues have a ring of Pearl about them—Jenny is fragmented, scattered, and utterly unable to see the truth of what is being presented to her (194-196).

Jenny’s point of view complex uses many similar devices to Pearl’s, with the only exception being a preponderance of scene. There are long passages of indirect interior monologue that dip into memory and reflection.

One key moment of reliability for Jenny, however, occurs when she is a suddenly single mother to an infant and she finds herself hitting her daughter in the same way her mother used to hit her (209).

Was this what it came to—that you never could escape? That certain things were doomed to continue, generation after generation? (209)

She reaches out to Pearl, who comes to stay two weeks and helps her. Jenny sees herself clearly for what she is becoming, and also sees her mother as a willing support she can draw on. She calls Pearl and wants to lash out at her but cries instead. It’s a plea for help.

In this way, each point of view complex gives us not just the way the characters see themselves and the world but how they see each other. Each one confirms or denies the others, operates in tandem or clashes with the others. Pearl for all her flaws does see the truth about her children. Cody despite his raging jealousy towards Ezra cAnneot help but acknowledge that none of it is Ezra’s direct doing. Jenny seeks Pearl out in the time of her greatest need despite her early experience with her mother. And Ezra absorbs everyone’s volatility, moving quietly through the family, finally getting his family dinner at the end.

The authorial voice, through the close third person narrating consciousness, uses a combination of language, syntax, diction, scene and memory among other devices to bring the reader into close proximity with the characters in the novel world to understand a family dynamic that is true to the human experience.

The Sound and The Fury

William Faulkner’s 1929 novel is the story of the Compson family. The dramatic action of the novel is set over four days: April 6-8, 1928 and June 2, 1910. The novel is told in four points of view: brothers Benjamin (Benjy, who is developmentally disabled), Quentin, and Jason, all in first person, and third person Dilsey, the long-time black servant who has helped raise all the children in the family. Each of the points of view focus on a few key events in the Compson household, most of them centering around the sister, Candace, or Caddy: Benjy’s recall of an incident in their childhood when they are out playing and Caddy’s undershorts get dirty; Quentin’s time in Harvard when he recalls Caddy’s pregnancy; Jason’s anger towards his brother Quentin, who killed himself, and towards Caddy and her daughter Miss Quentin, who the family has to take responsibility for and who ultimately runs away.

The modes of telling across the four points of view range from stream of consciousness to close third person with interior monologue across Benjy, Quentin’s, and Jason’s sections, and close third without interiority in Dilsey’s section, where the narrator/observer is just outside the character but does not give us any inner reflection.

William Faulkner

William Faulkner

.

Benjy

The novel opens with Benjy’s point of view. The narration is first-person stream of consciousness, with present action frequently dipping in and out of memory. The present action is set on April 7, 1928, when Benjy is thirty-three years old. The memories are when Benjy is a child and Caddy is seven (17) and later when she is fourteen (41) and he is thirteen (43). These ages are revealed in dialogue. The switches in time period are signaled by italicized text, often triggered by words or actions during the present, like when Benjy snags himself on a nail:

“Wait a minute.” Luster said. “You snagged on that nail again. Cant you never crawl through here without snagging on that nail.”

Caddy uncaught me and we crawled through. Uncle Maury said to not let anybody see us, so we better stop over, Caddy said. (4)

Benjy is incapable of speech, but he does observe things going on around him, though in a fragmented childlike way. The syntax is full of short, simple sentences, often missing punctuation. The narrative distance between the reader and Benjy’s mind is negligible, and there is no authorial filter of perception, so we see the world as though we are Benjy—the characters enter and exit scene and dialogue as though we have always known them. This makes parsing the information difficult, but not impossible. There are some markers of information that emerge over the course of the narration. Luster, for instance, is the man who takes care of Benjy in the present; Versh was in his childhood; and T.P. when he was thirteen. The reader also learns that there are two Quentins, a brother from Benjy’s childhood, and a girl in his present who is being brought up without her mother; two members of the family die, the father and Quentin the brother (11); and Caddy gets married and leaves the house (51).

None of these events, however, are formally revealed. The reader only gets to infer through an almost endless stream of scene and dialogue with no moments of contemplation. The lack of quiet reflection, the constant action and speech, Benjy’s crying and bellowing, all give the section an incessant noise, a cacophony, if you will—the sound of “the sound and the fury.”

The question of Benjy’s reliability is an interesting one to explore. Benjy slips in and out of memory, giving the reader a back story, but in no meaningful way to impact the present action. His function is like that of a camera—he records, and we get to see the playback, without judgment or interpretation, his or the author’s. He understands nothing but sees everything and reports it without critique.

While this style of narration makes the Compson world almost impenetrable for the first-time reader—there are no introductions or explanations of relationship dynamics, events, or setting—it does present their world in its most raw, unfiltered form. Scenes unfold and dialogue occurs in almost film-like fashion; the reader is quite literally a fly on the wall. What could be feel more credible than being an almost direct witness to action?

On the other hand, Benjy is the idiot from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth’s definition of life, “…a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” He embodies the very title of the novel. How can such a mind’s perspective be considered reliable? He cAnneot process information and cAnneot reflect on anything that goes on around him. And yet each of his memory recollections of the key events and people bears out in the remainder of the novel, like young Caddy’s muddy drawers being a significant childhood event, for instance, which Quentin recalls in his own memory in his section (152).

Also, we get the groundwork of the other point of view personalities: Jason, for instance, is as harsh and mean as his own point of view narration later reveals him to be. He is rude to his mother when she wants to visit the graveyard (11), he cuts up Benjy’s dolls when they are just children (65), and he argues with Miss Quentin telling her to get out of the house, which she promises to do (69-70). Her leaving is much of the focus of action in the last section of the novel.

Despite Benjy’s mental state, choosing him as the introducing consciousness does give us vital parts of the picture that we need to process the remainder of the novel, even though there is so much left to the reader to interpret that we feel unsure of the dynamics around him at first. But nothing depicted in Benjy’s narration is proved to be false, to my reading. So even though we lack the firm grounding of a developed mind and there is practically no distance between us as reader and Benjy as narrator or much authorial intervention at all, we still get a picture of the Compsons’ story, making Benjy lean towards the reliable side of the spectrum despite his mental incapacity for reflection or independent thought.

Quentin

The second part of the novel is set on June 2, 1910, when Quentin, Benjy’s brother, is at Harvard. He is cutting classes, is in trouble with the dean (78), but instead of going to class he leaves his room and roams the streets, where he meets a young girl who he calls “sister.” He ends up in trouble with the police and later, when he is freed, he goes to the river. Once again, the narration is first person. The distance between reader and narrator in this section moves between deep inside Quentin’s mind with his stream of consciousness to a more stable first-person narration with scene, dialogue, and interior monologue.

The dips into memory in this section, too, are signaled via italicized text. His narration, though coherent at first, quickly moves into unpunctuated stream of consciousness and becomes very shaky reflecting his downward spiral, thus putting his reliability in question. The syntax differs markedly from Benjy’s. While Benjy’s sentences were short clips, Quentin’s in many places tend to be long and run-on with no punctuation. Also, I found it significant that even though his narration appears coherent at first, there is missing punctuation right in the start of his narration, a signal that this is likely an already unstable mind:

When the shadow of the sash appeared on the curtains it was between seven and eight oclock and then I was in time again, hearing the watch. (76)

Quentin’s unreliability primarily stems from his obsession with Caddy’s promiscuity, and his fast-declining mental state. In one segment of memory recollection, for instance, he remembers the time when he tells Caddy that he will tell their father that they committed incest and that they are running away:

Ill tell Father then itll have to be because you love Father then well have to go away amid the pointing and the horror the clean flame Ill make you say we did Im stronger than you (149)

This is clearly not a reliable, rational mind. As the day progresses, Quentin’s thoughts get more and more tortured. He recalls a long exchange with Herbert (108-110), the man Caddy marries, followed by an exchange with Caddy when she tells him she’s sick (110-113) and that she has to marry Herbert. Later, his memory references the incident of Caddy’s muddy drawers that Benjy’s section also dealt with. This is a long, unpunctuated segment that starts on 149 and ends on 164. Caddy and Quentin’s relationship and the central incident of her pregnancy become clearer in this section. Towards the end, when his mind finally turns to the river and dying, again, the stream of consciousness takes over, his thoughts blend into one another and in this text, even the “I” turns into “i,” his sense of self diminishing to the point of dissolution. His final act is of suicide.

Despite his rambling thoughts, however, we do get to see some of Quentin’s world borne out by other points of view in the book thus giving him some reliability. Part of his recollection, for instance, is his mother’s view of the family and their lives (102-103). The segment began mid-scene during an encounter between Quentin and his roommate Shreve and quickly dips into unpunctuated memory in which his mother laments her misfortune at having had the children she has. This thinking of hers has appeared in Benjy’s recollection, too (“It’s a judgment on me. I sometimes wonder” 5). Two people recalling the same person in nearly the same way leads to a sense of reliability. Also, in Quentin’s memory, Jason is her favored son because “he is more Bascomb than Compson” (103), more like her own family than her husband’s. This bears out later in Jason’s section as well, when Caroline tells him that he is “the only one that isn’t a reproach to me.” (181)

Some of Quentin’s reliability also comes from the fact that though he is obsessed with Caddy, he isn’t blindly so and does not act on it. He thinks of incest, but he doesn’t carry through with it. He feels guilt at his thoughts. In his final stream of consciousness recollection, he remembers a conversation he had with his father in which he tells his father:

i was afraid to i was afraid she might and then it wouldnt have done any good (177)

He is conflicted within himself, much more so than Jason (Benjy, of course, has no inner reflection so cAnneot feel conflict in this way). So while his feelings for Caddy and his mental state leads to unreliability, he is still somewhat grounded in morality, making his worldview perhaps the most human of the three brothers.

Jason

The third section takes place one day before Benjy’s, on April 6, 1928. This section is also in first person, but the present action is far more linear. Seventeen-year-old Miss Quentin is the bane of Jason’s existence. He resents her, resents having had to take responsibility for her. Much of the action centers around confrontations between Jason and Quentin, Jason and his mother, interactions with the servants, memory of interactions with Caddy, and his present investments in cotton that prove volatile bringing further financial strain.

Jason embodies fury. His narration begins with him arguing with his mother over Caddy’s daughter Quentin. His mother is not able to control Quentin, and Jason feels like she never has:

“…You never have tried to do anything with her,” I says. “How do you expect to begin this late, when she’s seventeen years old?” (180)

Jason not only resents Quentin, he also resents the fact his brother was sent to Harvard while he was not; that Caddy’s pregnancy cost him his job at Herbert’s bank; that her baby’s birth and her eventual banishment was the shame of the family that led to their current situation, one in which Jason is the sole supporter of the entire household, including the servants who still work there.

While these could be justifiable feelings for anyone, Jason’s unreliability in the novel stems from his not dealing with these events honorably and having a persistently negative view of everything in his life. We have seen some of Jason as a child in Benjy’s section, when he cries at his grandmother’s death and when Caddy talks down to him. He has clearly been a sensitive child, but not the favored one. In his point of view section, he has grown up to become bitter, bigoted, full of rage with a sense of having been victimized by everyone, from his family and servants to blacks, Jews, foreigners, even the clients at the hardware store he works at.

He is prone to violence: he gets physical with young Quentin and nearly whips her with his belt (184-185). He also keeps the money Caddy sends for her daughter and does not spend on the child as she wishes. He justifies this by blaming her for his lost job:

And so I counted the money again that night and put it away, and I didn’t feel so bad. I says I reckon that’ll show you. I reckon you’ll know now that you cant beat me out of a job and get away with it. (205)

However, we have already seen Caddy’s suspicions of him at the beginning of this memory scene that bear out:

“Dont you trust me?” I says.

“No,” she says. “I know you. I grew up with you.” (204)

Also, while Benjy has no sense of his own feelings to engage with and Quentin engages with feelings to the point of self-destruction, Jason barely acknowledges them and does not engage with them much at all. At Quentin’s grave, for instance, the scene referenced above, he says:

“I got to feeling funny again, kind of mad or something, thinking about now we’d have Uncle Maury around the house all the time, running things like the way he left me to come home in the rain by myself.” (203)

But this “funny feeling” is left unexplored. He allows his jealousy of his brother to override any grief, is victimized by the memory of his uncle having left him in the rain and soon after, in a confrontation with Caddy, takes money from her in exchange for letting her see her daughter. He goes home and without telling anyone where he is taking the baby he goes to where he tells Caddy he will bring the child. But he only raises the child to the window and tells the driver to speed away, leaving Caddy chasing the carriage (204). His severely jaundiced view of his world and the brutality of his interaction with it is firmly established, and from here on there is nothing that brings him around to being someone whose view on anything can be relied on.

In a rare moment of inner clarity, however, he does admit his lack of conscience after a confrontation with Earl. Earl tells Jason that he is aware of how instead of investing the thousand dollars Caroline gave him in the shop, Jason appropriated it for himself and bought a car (228). He tells Jason that if Caroline ever wanted to know where the money went, he would tell her. Jason thinks to himself:

I never said anything more. …when a man gets it in his head that he’s got to tell something on you for your own good, goodnight. I’m glad I haven’t got the sort of conscience I’ve got to nurse like a sick puppy all the time. (228)

He boasts about how he could “take his business in one year and fix him so he’d never have to work again,” (228), but again Jason blames his mother Caroline and niece Quentin:

…how the hell can I do anything right, with that dam family and her not making any effort to control her nor any of them… (229)

In terms of language overlay and syntax, Jason’s is the most straightforward first-person account in the novel of all the three brothers. We are at close distance to him, have some passages of partially unpunctuated interior monologue, but in large part get a fairly coherent though rage-fueled narration as compared to the other two so far. Ultimately, Jason’s temper and continued resentment towards everyone around him are what lends his point of view its unreliability. Someone that prejudiced, bitter, and violent cAnneot see the world for what it is.

Dilsey

The fourth and last part of the novel, set on April 8, 1928, Easter Sunday, is told in third person omniscient, with description of setting, person, action, and dialogue, but very little interiority or thought. Here the authorial distance is far greater than the first three sections. The reader is close to Dilsey but doesn’t get much of her thinking, except when she speaks in direct dialogue. The first time we get any sense of interiority is when “Mrs Compson knew that she had lowered her face a little” (272). Even then, the action continues as close description from the outside.

The present action of this day centers around Dilsey taking Benjy to her own church for services, where the congregants are wary of the large, lumbering white man that he is. The household also finds out that young Miss Quentin has run away. For a while we shift to just outside Jason, as he finds Quentin’s room empty and the money gone. He calls the police and leaves to chase after Quentin. We shift back to Dilsey and the church service, and then to Jason again, when he is trying to report the theft and Quentin’s running away to the police. He leaves alone to chase her but loses track of her in Mottson. At the end we return to Dilsey, Luster, and Benjy. Luster is taking Benjy to the graveyard, but goes the wrong way around a monument, causing Benjy to start crying. Jason returns in time, slaps Luster away, turns the carriage around and they head home.

Dilsey is the novel’s moral compass, the reliable voice that translates and confirms motive and personality for us. After the heavily tortured and fractured points of view of the three brothers, Dilsey’s perspective—that of an eternal outsider in the household but fully aware of every dynamic—is soothing and focusing. Her perspective on the Compson family is what gives us our roadmap to understanding them.

Though we see Dilsey up close only in the last section, she has been a reliable presence throughout the novel appearing in scene, her voice heard in direct dialogue. She has tirelessly taken care of three generations of Compsons, from Caroline and Jason, to the four children, and now young Quentin, displaying a sense of unwavering duty towards the Compsons, though that doesn’t mean she blindly agrees with everyone or condones events.

Her reliability comes from the way she expresses her judgments about the family, calling out each character in turn for the natures they have: Caddy is “Satan” (45), her early mischievousness recognized as a precursor to her future transgressions; Benjy is the “Lawd’s chile” (317); Jason is “a cold man…if man you is” (207); Caroline in the beginning of the novel is “shamed” because she’s “projeckin with Queenie” the horse (10) her fears of dying and at the end Caroline “can’t see to read” (300), her inability to accept and control her family responsible for their undoing.

Dilsey’s attitude of duty stems from a sense of Christian piety, a religious belief of doing good and awaiting one’s reward later. This comes early in the novel, when she questions Benjy’s renaming:

Name aint going to help him. Hurt him, neither. Folks dont have no luck, changing names. My name been Dilsey since fore I could remember and it will be Dilsey when they’s long forgot me.

How will they know it’s Dilsey, when it’s long forgot, Dilsey, Caddy said.

It’ll be in the Book, honey, Dilsey said. Writ out.

Can you read it, Caddy said.

Wont have to, Dilsey said. They’ll read it for me. All I got to do is say Ise here. (58)

This piety is brought into focus in the last section of the novel when she goes to attend Easter services at the church, dressed in purple silk, with Benjy in tow despite Frony’s objections:

“I wish you wouldn’t keep on bringin him to church, mammy,” Frony said. “Folks talkin.” (290)

Dilsey, however, recognizes prejudice for what it is—and dismisses it with a rational voice:

“…de good Lawd dont keer whether he bright er or not.” (290)

The sermon is a key moment for Dilsey. When the preacher says he “sees de darkness en de death everlastin upon de generations” (296), the passage of time is brought into focus for her. She leaves the service and on the way home tells Frony:

“I seed de beginning, en now I sees de endin.” (297)

The sermon appears to give Dilsey a sense of her life and its significance in relation to the Compsons. When she returns home after the service, we see the house, the scene of action for much of the novel, described for the first time, a “square, paintless house with its rotting portico.” (298) And when Frony questions her on the goings on in the house, Dilsey tells Frony to “tend to yo business en let de whitefolks tend to deir’n.” (298) She understands that their lives, though entwined through the generations on a daily basis, do not carry over racial boundaries. They will always be separate. Her knowledge of her life and her world is grounded in reality.

While at first Faulkner’s approach to the narrating consciousnesses of the novels feels overly cumbersome, by the end each perspective stacked up against the other begins to make sense. In many ways, the distance of the last section is what ties the book together: the language overlay that is not resoundingly cacophonic (Benjy), tortured (Quentin), or enraged (Jason); the fact that there is a sense of quiet doing in the same way Dilsey has acted all her life with the family; the untroubled syntax with objective descriptions that allow the reader to see the novel world with its characters like Benjy:

His skin was dead looking and hairless; dropsical too, he moved with a shambling gait like a trained bear. His hair was pale and fine. It had been brushed smoothly down upon his brow like that of children in daguerreotypes. His eyes were clear, of the pale sweet blue of cornflowers, his thick mouth hung open, drooling a little. (274)

The distance between reader and narrator was extremely close to negligible in the first two parts, Jason’s rendering showed a little bit more distance, and in the last part we were pulled back out to see everything from just outside, though not too far. If reliability is an exercise in authorial distance, then The Sound and The Fury is an object lesson in how close one can get and be on precarious ground, and how steady one can feel even without the insight of thought.

Conclusion

The worlds of each of the three novels are as different as they could be. Each author draws on uniquely different lenses or consciousnesses to convey the truths or untruths of each world. All three use a range of distances for each point of view, sometimes taking the reader deep within, as though the reader is the character like with Benjy, sometimes moving far enough out like with Dilsey, and at other times staying close to and occasionally dipping into the character’s thoughts and perceptions like with the rest of the characters discussed. Each narrative choice paints a different picture when completed. Each narrative choice elicits a different response. These are just three examples of degrees of reliability in narration. The possibilities, like with the human experience, are endless.

—Rashmi Vaish

Works Cited

Booth, Wayne C. The Rhetoric of Fiction. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. Vintage Books, 1990.

Jauss, David. Alone With All That Could Happen: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom about the Craft of Fiction Writing. Writers Digest Books, 2008.

Kennedy, William. Ironweed. Penguin Books, 2006.

Tyler, Anne. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant: A Novel. Vintage Books, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017.

Rashmi Vaish is looking forward to graduating from Vermont College of Fine Arts with an MFA in Writing in July 2020. A former journalist, she now lives and writes in New York State’s North Country.

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature

Doris Lessing with 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh

Lessing’s parents, Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeigh Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons

Settler farm in Southern Rhodesia, early 1920s, via Wikimedia Commons Lessing with her mother and brother

Lessing with her mother and brother Doris Lessing, age 14

Doris Lessing, age 14 Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons

Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 1930 via Wikimedia Commons Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via

Cover and author photo from first British edition of The Grass is Singing, via  x

x

T. S. Eliot in 1923

T. S. Eliot in 1923 Young Tom Eliot

Young Tom Eliot

Mark Twain in 1882, two years before publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain in 1882, two years before publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Eads Bridge, St. Louis, Missouri, between 1873-1909, courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collection

Eads Bridge, St. Louis, Missouri, between 1873-1909, courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collection Twain with his family around the time Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published

Twain with his family around the time Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Tom, Jim, and Huck — Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Tom, Jim, and Huck — Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via  Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

Illustration by Edward W. Kemble from first ed., via

The Red Queen and the Red King in

The Red Queen and the Red King in

Henry Miller in Paris (photo by Brassaï)

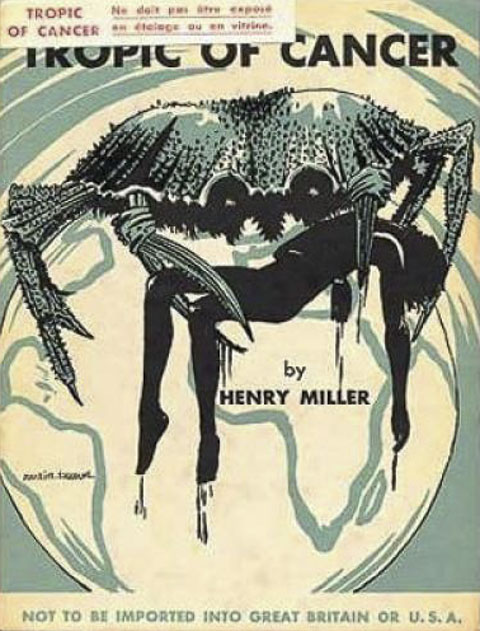

Henry Miller in Paris (photo by Brassaï) Cover of original edition, 1934

Cover of original edition, 1934

Wilson’s Dancing Studio, 1920 (photo from New York Public Library online archive via

Wilson’s Dancing Studio, 1920 (photo from New York Public Library online archive via  June Mansfield

June Mansfield  Paris cafe, 1930s

Paris cafe, 1930s Anaïs Nin

Anaïs Nin

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Wellington Street, downtown Chilliwack

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Cultus Lake, seen from Ryder Lake

Collections containing the essays.

Collections containing the essays. Joan Didion by Julian Wasser 1968

Joan Didion by Julian Wasser 1968 Elwyn Brooks “E. B.” White

Elwyn Brooks “E. B.” White

Yeats by George Charles Beresford, 1911

Yeats by George Charles Beresford, 1911 Yeats’s Rose Cross, Order of the Golden Dawn, photo © National Library of Ireland

Yeats’s Rose Cross, Order of the Golden Dawn, photo © National Library of Ireland Madame Blavatsky, photo taken between 1886 and 1888

Madame Blavatsky, photo taken between 1886 and 1888 Yeats’s Gyre

Yeats’s Gyre Maud Gonne in Cathleen Ni Houlihan

Maud Gonne in Cathleen Ni Houlihan Title page of Summum Bonum by Rosicrucian apologist Robert Fludd, 1629

Title page of Summum Bonum by Rosicrucian apologist Robert Fludd, 1629 Yeats later in life

Yeats later in life William Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar

William Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar Leda and the Swan by Jerzy Hulewicz, 1928

Leda and the Swan by Jerzy Hulewicz, 1928 Spinning room in a New England cotton mill, 1916, photo courtesy National Archives

Spinning room in a New England cotton mill, 1916, photo courtesy National Archives Archaeologist Henry Layard’s image of Nineveh

Archaeologist Henry Layard’s image of Nineveh Winding stair in Thoor Ballylee tower, photo by Walt Hunter via

Winding stair in Thoor Ballylee tower, photo by Walt Hunter via  Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne Yeats and his wife Georgie, late 1920s

Yeats and his wife Georgie, late 1920s

Cuchulain’s death, illustration by Stephen Reid, 1904

Cuchulain’s death, illustration by Stephen Reid, 1904 Bhutanese thanka of Mount Meru and the Buddhist universe, 19th century

Bhutanese thanka of Mount Meru and the Buddhist universe, 19th century