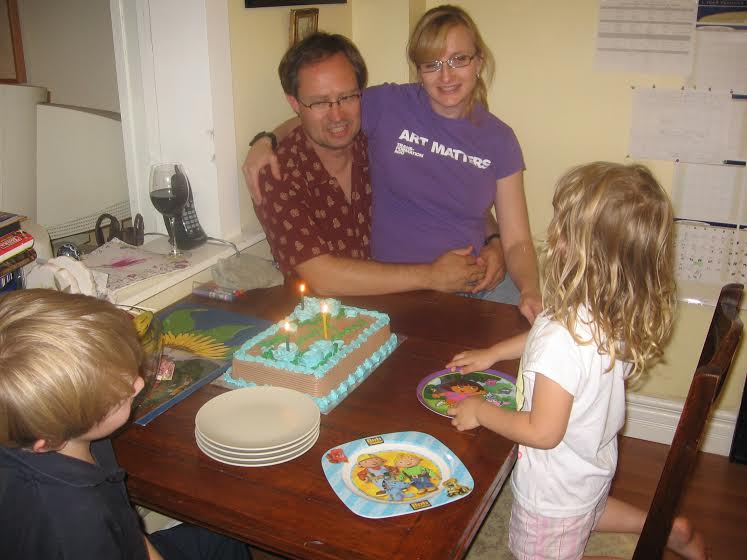

Michael and Kate

Michael and Kate

PART I (June 2014)

Two years ago I wrote an essay on returning to reading following the death of my wife. She was forty-four. We’d been married four years and nine months. She had breast cancer for twenty-one months. She left me with two kids (eight and eleven) and an ex-husband to negotiate. More accurately, she left her ex-husband with two kids and a second husband and step-parent to negotiate.

I intended to follow up my essay a year later with another on reading through grief, but I couldn’t manage it. The flow of grief left me unsettled to the extent that I never felt secure enough to speak. Never felt grounded, is what I mean. How could I write an essay on anything when every time I tried to put my thoughts together they shifted? Also, I had wanted to write how, one year later, I had “read through” grief, and about how I was now on the other side looking back. Except I wasn’t on the other side. Not only did I feel nowhere near the other side, I felt increasingly in ever deeper, ever more tumultuous water. For eighteen months, I felt concussed. And when those symptoms relieved, I felt something worse.

The grieved get used to people asking, “How’s it going? Better?” Things are supposed to get better. We have clichés for that. Time heals all wounds. We all know about the stages of grief. Denial. Anger. Sadness. Acceptance. As a grieved person, you are granted a certain leeway to be crazy. Emotionally overloaded. Out there. Behaving irrationally, unpredictably, outside the norm. And then you are supposed to “get over” all of that. You are supposed to acknowledge that folks have “allowed” you this period of disrupted expectations. You are supposed to be grateful how everyone has been “there for you,” which they have been, on the whole, even if it really seems that all anyone has really done is try to wait you out. Wait for you to declare, “I’m back.”

Early on I decided I was never going back. In my wife’s final months, I read The Five Ways We Grieve by Susan A. Berger and I’d absorbed the message that grief was transformative. You may respond to it in any number of ways, but you will not remain unchanged. After my wife died, I read Healing Through the Dark Emotions by Miriam Greenspan, a book recommended to me by one of my wife’s friends who’d lost her only son at age four to cancer. The transformation message was reprised there and to it was added a second: feel your feelings. Do not fear the darkness. Open your heart and mind and let the grief process carry you on its current. Healing will come in stages, and you will experience unexpected gifts.

I did experience unexpected gifts. Many involved suffering a rainbow of unremitting pain. All the better to teach you resiliency, my dear. Off in the distance a witch cackles. Ah haha. That I can write this now shows that I am released from this spell, which as I said was concussion-like. After my wife died, I chose to read Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett and Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. Woolf was my wife’s favorite author, and Mrs. Dalloway was her favorite book. I’d never read it, and I chose it to honour her. Waiting for Godot called to me. I felt I was caught in an absurd, Beckettian situation. I had spent so many hours sitting in hospital waiting rooms with my wife (waiting! rooms), so many months waiting for the disease to progress or not, so many weeks, then days, then suddenly minutes at the end, waiting for death. I felt I had confronted the void, and I felt I needed Beckett. Woolf, too. (And I did.) But what next?

I once made a list of the ten to twelve books I read that first year. It’s still around the house somewhere, but I’m not going to search for it. There were as many books, likely more, I started and set aside. I fell into no rhythm, felt no progression, struggled against despair. I believed in prescribing myself books. I felt I could self-medicate with literature and get through my hard times, but while some books clicked, in general I felt myself slipping downward. Of course, downward is a literary journey, too, but I decided against attempting Dante. Early on I tried Hamlet, a tale of grief and madness, and I thought it fantastic. I read it about the same period of time after my wife’s death as the period of time between the death of Hamlet’s father and the re-marriage of his mother. Too soon! Holy smokes! I also re-read T.S. Eliot’s essay on Hamlet and thought (again) that he was full of it. The capture of Hamlet by chaos and his urgent need for sense, pattern and meaning gripped me as perfectly sensible. Order had been overthrown, and what was it now?

In my own life, I had lost my role as husband and my role as a step-father became severely ambiguous. The children continue to spend time with me, but half what they spent before. The three of us were the ones closest to their mother, and we have a bond that has been forged in fire and is unbreakable, and my separation from them terrified me. If we can make it through seven more years, and get the youngest one out of high school, then we will have achieved something remarkable. It once seemed barely plausible. Now it seems more likely.

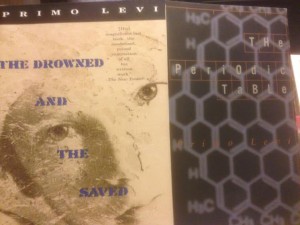

I decided to read Primo Levi. I started with The Periodic Table. I loved it. I wanted to stay with him forever. I thought, “This is what you do when you confront the void. You turn it into something like this.” Years earlier I had read Philip Roth’s interview with Levi. That was my only previous exposure to him. One of my wife’s friends had also told us a story about professional advice she’d received to help her deal with a toxic work environment. The advice was: read Holocaust literature. The premise was: it will make your toxic work environment seem less severe. At least that was her interpretation. I said, “Maybe it means your work is comparable to a concentration camp.” Except, of course, no mass murder. I had both interpretations in my mind when I started reading Levi. I had found the cancer period Beckettian, and the death administration equally so. Again and again I was confronted with the absurdities of our bureaucratic modernism. Trying to deal with my wife’s estate, I tried to process a cheque through the bank, but they wouldn’t do it. I complained to customer service, and got a lecture on the phone from a woman who explained to me that bank policy trumped the law. “We need to protect our customers,” she said. I explained to her that her customer was dead, and I was her husband and executor and that I WAS THE ONE who was responsible for protecting her, and the she was in fact thwarting her customer’s interests. No dice. I lost. I had to find another way of cashing the cheque.

Now that, it’s clear, isn’t a concentration type problem. No. Never. But the gift of Levi is his incredible ability to classify behaviours and identify sub-strata of groups within groups. Even in this darkest of dark environments, the concentration camp, the lager, Levi shows how meaning can be made and maintained, and how victims can create victims. As he notes, the survivors survived because often they were the ones who were able to find an advantage. An extra bowl of soup. An extra piece of bread. Avoiding beatings. Levi himself survived because of his chemistry training. He was put to work in a lab, and even then barely made it out alive. The Periodic Table is framed around chemistry. Each chapter is named after an element. It tells the story of his early life, his chemistry training, the rising anti-Jewish restrictions in Italy, his budding romances, his radicalization, capture and transport to the camp. The camp itself, and later liberation, his return to professional chemistry, and his interactions with Germans, both through his work at a paint factory and through his writings. What a profound life. What a profound contribution to humanity.

After reading The Periodic Table, I read The Drowned and the Saved, which I also found moving, but not as brilliant as The Periodic Table. I started to read Survival in Auschwitz, but put it down after a couple of dozen pages. My interest had shifted. I felt that Levi had given me as much as I could get from him at that time. I reflected on the horrible bureaucracy of the camps, the savage efficiency they implemented, and the homicidal logic they represented. Going through the healthcare system with my wife, we had often remarked, “You’re just a number.” When sit in the waiting (!) room, anticipating your five minutes with the world class specialist, lining up your questions, and wondering what koan he’s going to drop on you for the next week or three until you see him again, you remind yourself that he doesn’t know you. He doesn’t know your life, your ambitions, your dreams, or anything more about you than the list of numbers he sees on your chart, your blood work results, your hormone levels, your this and that and you don’t even know what because they won’t tell you. In the camps, though, you literally were a number, and it was tattooed on your arm, and the purpose of the camp was to kill you, while the purpose of the hospital is to save you. Except for many, they don’t. For my wife, they didn’t. After her mastectomy, back in her hospital room, she said, “I wonder where my breast is now,” and I said, “I know where it is. It’s in the lab.” Because that’s where the doctor had said it would be, to analyze the cells, and include the results in their database and research project. They had asked her permission to do this, of course, but that didn’t make her any less a statistic and a research subject. Catch-22. As a patient you want the benefit of that research, but as a patient you also want your doctor to see you as a human being. Sometimes this happened, and other times, not so much.

For eighteen months I felt concussed, but when that lifted, I felt worse. What was going on? Emotionally over-whelmed. Exhausted. I had survived the cancer period with the help of anti-depressants, anti-anxiety pills, sedatives, blood pressure meds, extra strength Tylenol, beer, wine, gin of increasing proportions. Little by little, I let go of those. The anti-depressants first, then the blood pressure meds. The need for Tylenol diminished. I cut the sedative dose in half. I tried to cut back on the drinking. I kept the anti-anxiety pills in reserve. I went to grief counselling. “Remember you have a body,” the counsellor said. You can’t think your way out of this. Like Miriam Greenspan said, feel your feelings. I wrote a blog throughout this period. I tried to chart my changing emotions. I felt I was getting better. I’m not sure I was getting better, only changing. I couldn’t convince myself that my wife was gone. I knew she was dead, but she felt present. I cried daily, often in sharp painful jags. They were just about the only thing that offered any relief.

What was going on? I had absorbed a blow so powerful, the bruise was taking months and months to work its way out. My head was a cloudy mess. I couldn’t anticipate a future. I tried to write new fiction, but I couldn’t. I could barely read, and often I couldn’t. Television struck me as trivial and dull. The news attracted me not at all. In her final months, my wife had spent a lot of time playing Scrabble on the ipad. I couldn’t even open that application, but I sat most evenings and weekends (when the kids weren’t here) plugging away at various online strategy games. And then I downloaded Candy Crush Saga. The distance between The Periodic Table and Candy Crush Saga, I’m here to tell you, isn’t as vast as it first seems. The attraction, in fact, was similar. At least in my case. Each both excited and calmed my mind, took the random and chaotic and led it into patterns, filled up the time on the clock. Time heals all wounds, the cliché says. Not so, but wounds do need time to heal. Some lots of time, months, even years. As I am relieved from one wound, I seem to confront yet another and then another. Through the cancer period, we looked only forward, never back, and it was a horrible time that we filled with much joy (because we were alive and together and it was our mission), and at first I thought my wound was her death, but after eighteen months I realized that it was also the way she had died. Just the other day, while I was at work in the office, I found myself asking: “Dear God, Why? If you had wanted to take her, why didn’t you just take her? Why did she need to suffer so first?” Thinking like this, makes me think the comparison to the concentration camps isn’t so misplaced. Except one is an act of God, and the other an act of Man.

In March 2014, I felt violent palpitations remembering her mastectomy surgery in March 2011. The memories came upon me suddenly, unexpectedly. I tried to puzzle out why. I had violent images of her scar and “drainage tubes” and her pain and struggle to overcome the loss of muscle under her arm also removed. At the time, we had remained calm, focused, constructive, forward-looking. In 2012, we hadn’t been looking back. Things for her we so much worse. In 2013, I had only been thinking about 2012, her last months, the process of her dying. In 2014, my memory took me back to 2011. I felt ill. I took a couple of days off work. I felt violently shaken with disbelief that they had cut her breast off. Oh my fucking God! What savagery is that!? And we had just let it happen. We had been glad that it happened. We had praised the good work of the surgeon. What a clean, beautiful scar line! All of this seemed impossible to me now. No way. How horrible all of that was. How abnormal. How perverse. What knots we tied ourselves in to make it all seem permissible. No. It was brutal and horrible and a lasting terror. And then, as quickly as they had come, those dark feelings lifted.

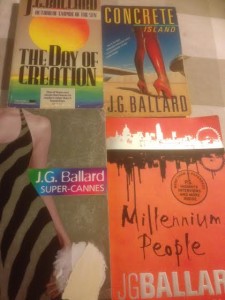

I read three J.G. Ballard novels in the first year after my wife died, and one more in the second. First three: Concrete Island, The Day of Creation, Super-Cannes. The forth: Millennium People. I had read Cocaine Nights previously, and some of his short stories. I had a sense that Ballard would be good to read, and he was. Why?

.

PART II (Nov 2014)

It is now over four months since I wrote the first part of this essay, and I have not written a word towards answering that one word question. Life intervened, and also writing the first part of this essay exhausted me. Reading it recently, I was surprised by the anger it contains. I remembered it as “cool” and “dispassionate,” but it is nothing of the sort. I had written about my wife, Kate, without naming her, a distancing strategy. Coming to terms with grief requires a distancing strategy. It is a distancing strategy. Letting go of the past. Trying to get up some momentum for the future.

In September I attended a three-day “Camp Widow” conference in Toronto. Organized by Soaring Spirits International, a California-based grief support organization, this event brought together 120 widowed individuals (110 women, 10 men) and offered a variety of workshops, seminars and peer support opportunities. I wasn’t sure I would like it. I wasn’t sure I would get anything out of it. But I did like it, and I did get a renewed sense of vigor and momentum out of it. Primarily, it helped me realign my heart and my head, accept that I am a widower now, and a widower forever, and understand, perhaps for the first time, that moving on does not require letting go.

I mean, I knew that. I was living that. But this is where the peer support was so important. In my life, I have no peers. I know no one my age who has lost a spouse. People my age tell me things like, “Divorce is like a death.” And they tell me how horrible it was to lose a parent. These events are horrible, and painful, but these people are not my peers. I go to work day after day and try to be a productive person, but my sense of belonging in my life is shattered. Everyone wants me to get “back to normal,” but there is no normal to go back to. If I have a new normal, it will be something I need to build out of the shattered remains of my former life. “Camp Widow” made that crystal clear.

J.G. Ballard was a widower. His wife died in 1964, suddenly from pneumonia, leaving him to raise three children. Of course, he had also spent part of his childhood in a prisoner of war camp in Shanghai. His novels chart the shattered remains of the (post-)modern world. Life after the catastrophe. If Levi was life within (and after) the catastrophe, Ballard is also charting “after the end.” I felt at home in these novels, which are more often read as pre-apocalyptic visions, but I think that’s a misreading. One paraphrase I read in a book on grief noted Heidegger said it was best to live as if the end had already come. This is exactly how I felt after Kate died. Where was I? How could she suddenly be gone? How could we be separated? That wasn’t supposed to happen. What was this place, without her? It wasn’t the world I had known. It was a place “after the end.” I felt pain, but I also felt free in a way I had never felt before. I could do anything, anything at all, and yet all I wanted to do was nothing. Just sit in front of a fire in the woods and poke at it with a stick.

I told these thoughts to a friend, and he told me about Walter Benjamin and his Angel of History:

A Klee drawing named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

I believe I had said to my friend that Kate’s death had freed me into a land of infinite choice, and yet I felt powerless. The world rumbled on, and I watched it in horror, wondering why it was full of shit. Violence. Madness. Degradation of such variety it was impossible to keep up. None of this was necessary, and yet none of it could be stopped. I seemed to have a front row seat and an awareness heightened beyond anything I had ever experienced. Propelled backwards into the future, we go. Fuck ya.

Concrete Island (1973) is a retelling of Robinson Crusoe, except the island is a traffic island lost in a sea of traffic lanes and overpasses. It’s a slim book, and if I wasn’t specifically interested in Ballard I don’t think I would have picked it up, but it gripped me. A middle-aged man on his way home from a rendez vous with his mistress goes over the barrier in his fancy car, rolls down a hill and is trapped in an odd parallel universe, which is within reality and also outside of it. He discovers the island has other denizens, a self-supporting ecosystem, and no way to escape. His expectations of life are fundamentally and suddenly altered, and he must adjust, or die. I identified with that.

The Day of Creation (1987) is also an “after the end” novel. The action takes place in Central Africa, a parched and desert-like place. An Englishman, Doctor Mallory, goes on a Heart of Darkness-type quest after a mysterious river is suddenly sprung free from the earth. In a chaotic world, ruled by paramilitaries, bureaucrats and a freelance television crew, Mallory brakes free and leads all and sundry upriver, seeking its source. There’s some high adventure in this one, but also lots about a world under stress from capitalism, militarism, technological expansion and, let’s just say it, men. The mystery of the natural world is set against all of this. The power of women and girls, too. The new great river. The land mass of the African continent. A wild, post-pubescent, silent girl, who enters carrying a gun, and is equally terrifying and heartbreaking. The novel quickly reveals the foolhardiness of those who think they “know” anything about anything. Propelled backwards into the future, we go. Fuck ya.

Super-Cannes (2000) takes us into a world of ultra-capitalism and a different kind of desert, a kind of intentional community, though it is built for Forbes 500 companies, not 1960s back of the landers. It is also a post-catastrophe novel, in this case a murder rampage which had disturbed the perfectly controlled, micro-managed village just before the arrival of the protagonists, a husband and wife. She is the new doctor (replacing the doctor turned mass murderer), and her husband is the narrator, who has a lot of free time to investigate the goings on of his new surroundings. The genre explored here is whodunit? Or more precisely, whydunit? The plot thickens and thickens, as our hero is introduced to the reigning psychiatrist, who explains the theory and practice of the super village. It is designed to take care of its residents’ every need, so that they can be as productive as possible, and rake in the dough for the multinationals who are paying all of the bills. Taking care of everyone’s needs leads to an unexpected result. Folks are bored. All work and no play, it turns out, isn’t healthy, and the dark side of the soul needs to be exercised. So the folks organize under-the-cover-of-darkness vandalism brigades. Plus much more. I didn’t identify with the plot here, not in a “post-grief” way. But the undercurrent of swirling chaos felt very real. It made me think of the cancer period. It made me think of the dark truths hidden by systems.

Millennium People (2003) continues down this path. The action is set in contemporary England. A bomb has gone off at Heathrow, in the arrivals luggage area. The protagonist is a senior psychologist and his ex-wife is among those killed by the bomb. Through his job, he becomes involved in the investigation, but he begins his own independent research as well, getting drawn deeper and deeper into a shadowy world of domestic terrorism and anti-capitalist rebellion. The book contains an enlarged critique of big money and the faux surface “realities” of consumer culture and mass media. As with Super-Cannes, the plot plays with the idea that violence leads to a truer engagement with life, an idea that Ballard has returned to for decades. See, for example, Crash (1973), where characters stage car accidents for sexual pleasure. I found Millennium People to be the least satisfying of the four Ballard novels I read in this sequence. Some of the ideas felt recycled. The protagonists were starting to blur together. But the insights about an outer shell of mass media images obscuring and inner crust of essential “being” expressed what I felt to be intuitively true in my post-grief blurriness.

Being in a “liminal” world, is something Kate spoke about, as she lived with terminal cancer. Liminal = in between, life and death, here and there, fear and hope. And so on. I often felt in that space, too. Outside the main flow of life. And as I watched her die I felt as close as you can get to the other side without slipping into the void. Kate had spoken to a friend about the writing of Stephen Jenkinson, a palliative care specialist. She seemed to like what he had to say, but we didn’t talk about it much. She didn’t like to talk about dying, at least with me. She wanted us to just life, stay in our groove. But one of the things Jenkinson focuses on is fear, confronting fear, specifically. One story he tells is how most people when they confront death, aren’t actually confronting death; they’re too lost in the fear. He says that meeting death is like meeting love. You meet a new lover and at first you confront feelings of anxiety and uncertainty. Is this going to work out? Can I actually connect with that person? And you go through those emotions, and then you connect with love. Connecting with death is the same, he says. And that describes what I felt, waiting, watching Kate get sicker, knowing that death would come soon, but never really sure when. Months, then weeks, then days. Imminently.

Five days before she died we were at the hospital for the last time, and her bloodwork was terrible. The numbers were not good, and she knew what that meant. She said, “I guess this is it.” Later, she asked me what my biggest fear was. I said it wasn’t that she was going to die. I wasn’t afraid about that. Now, reflecting on then, I’m stunned. We were there with death and we were both, “Oh, well. I guess it’s really going to happen.” The fears I had were about what would happen after she died. I told her that, but I also told her that I knew she didn’t want to discuss any of that with me. She didn’t. We sat in the sun outside the hospital, and I told her I wished we could just stay there forever. It wasn’t the disease that was the problem; it was time. We said some other things to each other also. It was really beautiful. Then we had to go home and re-enter reality and play the drama out. Three days later she was no longer speaking. She died two days after that.

Have I made it clear how Ballard’s multiple levels of reality felt just right to me? I hope so.

Just recently I recounted Jenkinson’s story about going through fear to get to death to my psychologist. I wanted to make the point to him that nobody told me I would have to go back through the ring of fear to get back into ordinary life. For a long time, I didn’t want anything to do with ordinary life. I liked being in the liminal space. I wanted to just stay there. It was a place full of insight, and a level of quiet peace that was sustaining, even if not fully real. But you can’t stay there. At least, I couldn’t. It’s that infernal engine of time again (another of Ballard’s obsessions, also; there’s some fantastic short stories that attack time savagely, but that’s for another…well…). Time wouldn’t let me drift in a void-like space for long, and getting back to a sense of normalcy was very, very painful. Ballard didn’t help with that. Levi, not so much, either.

I didn’t seek out novels about grief. I tried to read Murakami’s nonfiction about the sarin gas attack. I couldn’t get into it. I thought I would feel an “after the end” connection to it, but I didn’t.

On the first Valentine’s Day after Kate’s death, I bought Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000). God, I hated this book when it came out. Everyone who told me about it made it sound horrible. I found the title unforgiveable. I had tried to read a number of different Eggers titles and found them unwelcoming to my tastes. But Kate liked his stuff. And this was a novel about grief and moving through it and past it, and in a moment of perversity I bought it, then devoured it quickly. I then put it on the shelf with Kate’s other Eggers titles (her books are still separate from mine). I felt, in a way, that I had read it for her. I know that sounds weird. There was more than a little magical thinking going on. I really hated the “Dave” character, pretty much all the way through, but I also got what he was doing, and I knew that I only got it because I was going through something so, so similar. I felt that I was in a place that only I could understand, and I was having visions that were like x-rays, but I knew none of this was because of genius, and also that it was heartbreaking in a quotidian way. It was pretty simple. My wife had died when I was 43. I had been 38 when we married. Eggers was in his early twenties when both of his parents had died from cancer in short succession, leaving him with custody of his much younger brother. Holy fuck, I thought. Now that’s a raw deal. And the novel is often raw, and sometimes it’s just plain stupid, but it is a song of pain that is staggering, heartbreaking, and even, yes, at times, genius. But it still left me trapped in Jenkinson’s wall of fear.

Julian Barnes lost is wife in 2008, suddenly to cancer. In 2013, he published Levels of Life, a memoir of his grief. In 2011, he published The Sense of an Ending, a novel deeply reflective of the mysteries that haunt our lives. I read both of these books in close succession in the past year, and they are each remarkable and each marked, I believe, with the sharp pain and clarity of vision that grief can bring. Levels of Life is specifically about Barnes’ own grief and he tells of hard, hurting moments, but he also gives us a magical story about balloons. It’s really amazing, how he grounds the reader with enormous weight, and also makes us feel lighter than air. This is an incredible book, and it lifted my heart. The Sense of an Ending is also an incredible book, and now that I think about it it has grief at its core also. The protagonist is an older man, reflecting on the death of a close friend when he was young. Recent events draw him back into the past, and he discovers that things he thought were so, weren’t at all. He wonders if he has made a mess of his life, but he is not without opportunities to correct it, at least partly. I bought this book at Heathrow on a visit to London, and read it in the lounge and on the plane, completing it before landing in Toronto. Both of these Barnes titles are about transition, and in the past two-and-a-half years that has been my life, over and over. Will this bloody transition ever end?

I was already feeling a new sense of something when I went to “Camp Widow,” but that experience broke open emotions I hadn’t felt in a long time. It made me realize and articulate, finally, that Kate would never leave me and that I would also move on past her, and that these two facts weren’t in contradiction. She will always be with me, but I can’t stay here, in the now, which is the past. What is that thing, that sense of an ending? Is it a different level of life? I will have my own, new future, and she will be part of it, but she also won’t be part of it. Is that what happens when you get old? You realize that the past is always with you, and nothing ever really ends?

I said to my psychologist, “Returning to ordinary life is fucking horrible. Ordinary life is fucking horrible.” I meant this in an Angel of History way, but also just: my magical powers are fading. Grief is an extraordinary emotion, and living deep in grief is an extraordinary experience. At “Camp Widow” I heard of others who had contemplated suicide, others who had succeeded. Going back through the ring of fear and re-entering ordinary life is a risky period of “time.” To let go of the magic of the grief: hard. To let go of the dreams of being with the loved one: hard. To accept the new reality of here/not here: hard. Some don’t make it. Eggers’s older sister didn’t make it. Barnes muses about suicide as an option. Levi either killed himself or died in an accidental fall. Ballard’s vision includes violence as a kind of release. I was never suicidal, but one question pounded in centre of my mind: why should I go on? Why, without her? As I have gone on, I’ve realized again and again that I’m not without her. I don’t know how to explain that, except I have a glowing certainty that it’s so. And my PTSD pain, the memories of her suffering, etc., fades, too. The soul is lighter than air, it rises like a balloon.

.

CODA

Okay, the PTSD pain. Yes, it fades, but it also comes and goes. The concept of “trigger warnings” is growing in common usage, and I was initially skeptical. I’m naturally skeptical. But the first week of November, the date I’m writing this, is the week Kate had her first chemotherapy. I’m self-conscious of anniversaries, and careful. Better to anticipate feeling crappy than to have it sneak up on you. Well, this week snuck up on me. Yesterday I felt like utter crap. Not as bad as I have often in the past, but worse than I’ve felt in a while. What happened at this time? I asked myself, and then I knew.

Here’s the thing about that first chemotherapy. We took a video camera. I have about a dozen video files of Kate from that day after various stages of the process. I had forgotten that entirely and then a while back found these files. We must have been crazy. We were crazy. Kate was adamant, however, that the disease wasn’t going to change her. She is seen plugged up to the machine and laughing. She is seen at home in bed, towel on her head, complaining of a headache and laughing. In one video she has the camera and she points it at me. I make a funny face. Looking at her doesn’t automatically make me sad any more. Looking at myself, was shocking.

I want to be that guy again, but I cannot. Nor can I tell him, buddy, hold on. You are in for a wild ride. If there was one thing I could tell him (me), it would be that the strategy of laughing your way through cancer will fall apart. You may think, dude, that cancer was bad; and it was; but losing her, this will be worse. (You will not laugh your way through grief, though your step-daughter will expect it of you. So like her mother, she will say, “I don’t like to see you cry.”) To put it in terms of this essay, I read and wrote through the cancer period. I clung to my reading (as did Kate) like a life raft. I read in many hospital waiting rooms. I wrote a book review weeks before she died. All of that fell apart in the tunnel of grief. This essay has been about putting my reading life back together. I have piles of books scattered all over the house, as I did before she died. I am reading widely and randomly, as I have always liked to do. On this good news, I will end.

— Michael Bryson [1]

Link to Kate’s Photos: http://kateorourkephotos.

.

Michael Bryson has been reviewing books for twenty years and publishing short stories almost as long. His latest publication is a story “Survival” at Found Press. In 2011, he published an e-version of his novella Only A Lower Paradise: A Story About Fallen Angels and Confusion on Planet Earth. His other books are Thirteen Shades of Black and White (1999), The Lizard (2009) and How Many Girlfriends (2010). In 1999, he founded the online literary magazine, The Danforth Review, and published 26 issues of fiction, etcetera, before taking a break in 2009. TDR resumed publication in 2011. He blogs at the Underground Book Club.

/

/

-

Here’s a short list of some books I’ve read recently that I’m enthusiastic about:

Mad Hope, Heather Birrell

How Should a Person Be?, Sheila Heti

Why Be Happy When You Could be Normal?, Jeanette Winterson

Nothing Looks Familiar, Shawn Syms

Interference, Michelle Berry

Polyamorous Love Song, Jacab Wren

Bourgeois Empire, Evie Christie

The Desperates, Greg Kearney

You Must Work Harder to Write Poetry of Excellence, Donato Mancini

The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fist Fight in Heaven, Sherman Alexi

Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Cambell Scott, Mark AbleyHere’s some books I hope to get to soon:

Inherent Vice, Thomas Pynchon

What Would Lynne Tillman Do?, Lynne Tillman

Come Back, Sky Gilbert

Stories in a New Skin, Keavy Martin

All the Broken Things, Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer

I know you are but what am I?, Heather Birrell

Ellen in Pieces, Caroline Adderson

The Outer Harbour, Wayne Compton

Girl Runner, Carrie Snyder

Life is about losing everything, Lynn Crosbie

Sad Peninsula, Mark Sampson

Gender Failure, Rae Spoon and Ivan E. Coyote

In the Language of Love, Diane Schoemperlen

Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson

Boundary Problems, Greg Bechtel

All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews

The Incomparables, Alexandra Leggat

Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed, Jacob Wren

Professor Borges, Borges

Rap, Race, and Reality, Chuck D

The Collected Stories of Stephan Zweig

Tobacco Wars, Paul Seesequasis

Voluptuous Pleasure, Marianne Apostolides

Sophrosyne, Marianne Apostolides

Consumed, David CronenbergRead on.↵

Roger Weingarten

Roger Weingarten