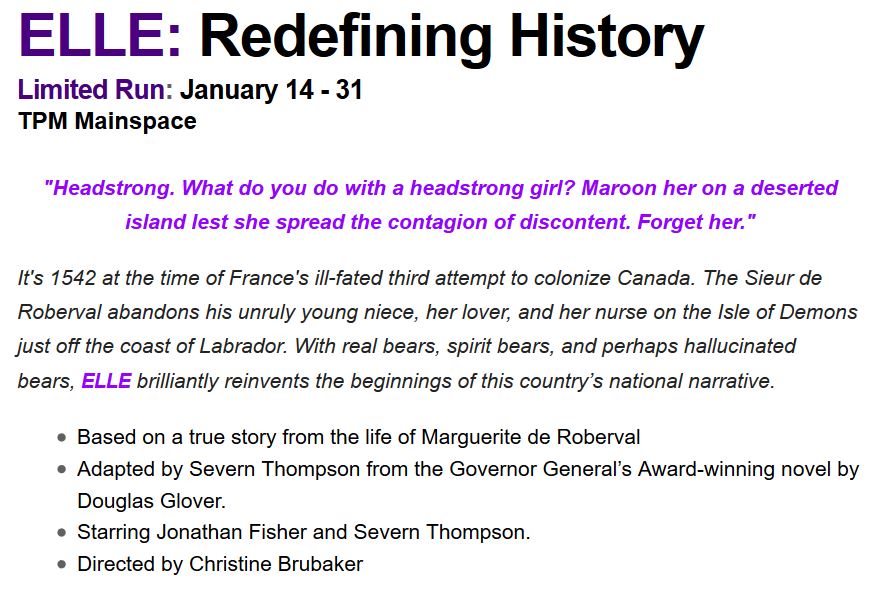

Audible has just (September 13) released the audiobook version of my novel Elle. This audio version is narrated by the replendent Severn Thompson who adapted the novel for the stage last year. Click the image above to go to Amazon and hear a sample of the novel.

Here’s yet another news item out of Winnipeg where Elle, the play, is currently enjoying a three-week run (through to March 12).

The latest play at the Prairie Theatre Exchange is required viewing for anyone who wants to catch up on Canadian history usually shrouded in shadows. Elle is a touring production from Toronto-based Theatre Passe Muraille.

Severn Thompson stars as the titular character and Jonathan Fisher features in a supporting role. Thompson adapted the play from Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel of the same name.

“I discovered (the story) from a book in my grandmother’s bookshelf. It had won the Governor General’s prize, but I had somehow missed that in 2003,” Thompson said in an interview Tuesday.

“When I finally read it, it just was illuminating to me of a time in history that I thought was fairly – hmm, I don’t want to be rude – but fairly dull from my memory of early school days,” she said, laughing.

Source: Toronto play ‘Elle’ illuminates atypical colonizer-colonized roles | Metro Winnipeg

First review from the Winnipeg run, and it’s good. Go Severn!

What makes it work as well as it does is that Thompson puts the narrative inside her heroine’s head. She comes to this new country with a completely inadequate dictionary of Indian words written by Cartier himself. By the time she meets a real native, an Inuit hunter named Itslk (Jonathan Fisher), she achieves equilibrium with him because he understands the woman’s new lexicon of dreams and visions as well as he happens to understand French.

The upshot of the play an be glibly summarized: You don’t inhabit the land; the land inhabits you.

But that would diminish the richness of the work, and especially of the character, brought to vivid life by Thompson’s performance, alternately comic, tragic, and bracingly primal.

Read the rest: Fight for survival in 1542 – Winnipeg Free Press

Here’s an interview with Severn Thompson, the actress and playwright who adapted Elle for the stage and who has made the role her own. This is in the venerable prairie newspaper, the Winnipeg Free Press. The play opens tonight at the Prairie Theatre Exchange and runs till March 12.

“She was somewhat rude and she had this impulsiveness. She had strong appetites, including sexual appetites, which get her into trouble,” Thompson says. “And like me, she resorts to humour when things get bad. That was one of her coping mechanisms and I just really appreciated that.

“She was shaped by the 16th-century aristocratic culture that she came from, but definitely lived on the fringes of it,” Thompson says. “She was a misfit.

“She had no interest in being a wife or a nun and those were the two options really available to her,” Thompson says. “In this account, she volunteered to go on this journey to see a new world. I don’t think she had plans to live there for the rest of her life. She wanted to have an adventure and see something she wasn’t familiar with.”She had no idea what she was getting herself into.”

Elle, the play, opens in Winnipeg at the Prairie Theatre Exchange tomorrow (February 23) night. I am told that tonight’s preview performance is sold out (upwards of 300 seats). Go Winnipeg!

This is the Theatre Passe Muraille production on tour. With Severn Thompson as Elle (she adapted the play from my novel) and Jonathan Fisher.

Some very nice poster art to go with the play.

Winnipeg performances run February 23 – March 12. Tickets and schedule here.

I don’t know Lincoln Kaye, but anybody who calls me a “CanLit superstar” is okay in my books and will no doubt find a special spot waiting for him in Heaven. The reviews coming out of Vancouver have been great, but this might be the best (and not just because he calls me a “CanLit superstar”). Here’s a quote. Follow the link below to read the rest.

And it’s as “Elle,” an unnameable, unimaginable “she”-bear, that she impossibly manifests in a Paris cemetery to maul to death the perfidious uncle decades after that ill-starred outbound Canadian voyage.

In Thompson’s commanding stage presence, all these “Elle” avatars nest within each other like Matryoshka dolls. Her body language and her stream-of-consciousness narrative slide fluidly backward and forward along the story-line, just like the text of CanLit superstar Douglas Glover’s novel from which Thompson herself adapted the script.

Read the rest of this scintillating review at the Vancouver Observer.

Here’s a generous and smart take on Elle, the play, from a critic and writer — Colin Thomas — who saw it the second night in Vancouver. I like the part where he says the audience was “deliriously appreciative.”

As if that starting point weren’t already thrilling enough, Glover and Thompson have wrought a magical realist telling of Marguerite’s story in which they explore—poetically and with great humour—themes of female sexuality, colonialism, and our spiritual relationship to nature. As Marguerite struggles for survival, killing birds and eating books, as she starves and hallucinates, as she rubs up against First Nations cultures and experiences the pull of a different world view, the shadow sides of patriarchy and colonialism gain force. Marguerite’s femaleness, her untamable libido, the relentless beauty of the wilderness, and her growing understanding of the fluid relationship between humans and animals, between waking reality and dreams; all of this pulls Marguerite apart and reshapes her. She has heard, vaguely, of a First Nations god, whose help she solicits—at a price. “One god guarantees my faith is true,” she says. “Two makes it a joke.” Marguerite begins to turn into a bear. “You cannot inhabit,” she says, “without being inhabited.”

The play’s language is as rich as its ideas—and it’s unpretentious. The fog off the coast is “as thick and oily as fleece.” “The smell of this new world is so fresh it has almost no smell at all.” And I mentioned humour. When Marguerite sees human footprints in the snow, she says, “A man was here. And now he is gone. I am suddenly not dead. It feels like a social life.”

More press out of Vancouver. Here’s a quote, Severn Thompson talking about the process of adapting the novel.

“It’s the story of survival that most of us missed in our history classes,” Thompson explained.

An admirer of historical fiction, the actor quickly saw the potential of showcasing Elle on the stage.

“It was very visceral and rude and funny in a way that historical fiction isn’t usually allowed to be, especially when involving women,” she enthused.

It took more than two years for her to adapt the work. Full of literary references and philosophical tangents, Elle is a complex book.

“That was the hardest part, really: whittling away at all these wonderful aspects of the novel,” Thompson said. “But the play hopefully brings it even more to life. From what I hear from people who see it, they feel spent but inspired by the end of the piece.”

Here’s a teaser from an interview Severn Thompson did with the Vancouver Sun.

Q: Elle opens with the main character engaged in what one review called “frantic fornication.” Was that also part of that early version?

A: Yes, with a chair. (Except for one other small part, Elle is a one-woman play, with Thompson occasionally using props). And he (Glover) came with his son. And my family was there too. I tried not to think too much about it.

Outside the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford

Outside the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford

The 2017 winter tour of Elle, the play, started in the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford, Ontario, January 26 – February 4. I’m a little reticent about the experience. More than I can translate into words. My ancient mother got to see the play for the first time (she remembered 2003, making the trip to Ottawa to see the Governor-General’s Award ceremony). My sons came on closing night. The play was better than a year ago. I thought I might be impervious, but it sucked me into the dream. There were standing ovations. There was a champagne reception. Keith Rainey came up to me after and I reminded him that when I was in Grade One, in the little stone one-room school house at Dundurn (eight grades in one room), he had played Bob Cratchit to my Tiny Tim in the Christmas concert. My father made me a crutch and a leg brace out of soup cans and old horse harness and we drank apple juice for wine and I got to say the words, “God bless us, every one!” My first brush with theatre.

dg

DG and Amber Homeniuk during the talkback after the last performance

DG and Amber Homeniuk during the talkback after the last performance

Taking pictures during the champagne reception after the show

Taking pictures during the champagne reception after the show

Top row l-r: Severn Thompson, Paul Thompson (legend of Canadian theatre, Severn’s father), dg, and Amber Homeniuk, master of ceremonies. Bottom row: Claire Senko, Old Town Hall Theatre artistic director, and Jonathan Fisher

Top row l-r: Severn Thompson, Paul Thompson (legend of Canadian theatre, Severn’s father), dg, and Amber Homeniuk, master of ceremonies. Bottom row: Claire Senko, Old Town Hall Theatre artistic director, and Jonathan Fisher

DG with multiple NC contributors Jonah Glover and Jacob Glover

DG with multiple NC contributors Jonah Glover and Jacob Glover

And here’s another review of the Vancouver production of Elle, at the Firehall Arts Centre till February 18.

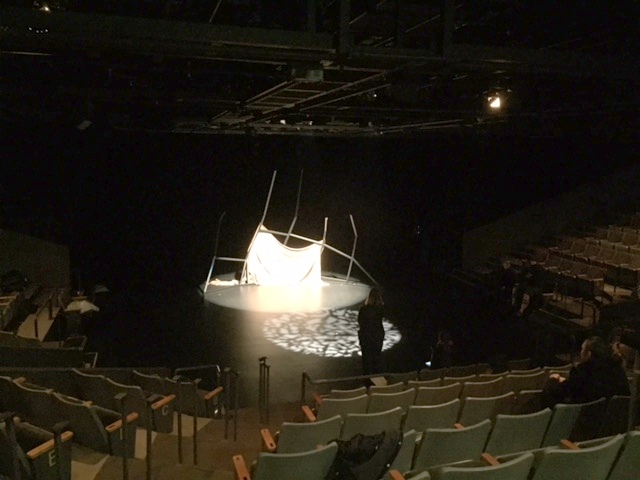

Thompson is a riveting performer with a rich voice and big emotional range, and director Christine Brubaker’s minimalist approach to the staging offers many pleasures. In Jennifer Goodman’s set, a structure of bent bars looms at the back of the stage, and a single piece of cloth becomes a sail, a hut, a fire, a bear cub, and so much more. Lyon Smith’s spare, otherworldly music is performed live by Jonathan Fisher, who also plays Itslk. And Goodman’s textured lighting enhances the magic-realist qualities of Elle’s story.

Delightful review of the Vancouver production of Elle, the play, at the Firehall Arts Centre. This is in Room, the fine and venerable feminist literary magazine.

dg

Playing Elle—who is something of an antihero, never without her flask—Thompson is a powerhouse from start to finish. Five minutes in and we see her energetically miming a sexcapade with her somewhat inadequate, tennis-obsessed lover, and from then on her energy (and healthy libido) hardly wavers. She delivers ninety minutes of vibrant, darkly funny text (it’s nearly a one-woman show) and though her character is desperately exhausted throughout, Thompson herself is not.

Severn Thompson as Elle via Now Magazine.

Severn Thompson as Elle via Now Magazine.

I’m a little slow on this. The story came out in December. But it’s a huge vote of confidence for Severn Thompson to add the to Dora Award nomination for Elle, the play, earlier in the year.

dg

You only had to watch Thompson, off to the side in a scene from Breathing Corpses, weep silent tears to realize how committed she is to her roles. She had a wider emotional scope in the terrific historic feminist script Elle, which she adapted as well as starred in. As talented a director as she is an actor, she co-created and helmed Madam Mao, which focused on another strong female character, and later directed a light, inventive staging of Peter Pan, set in various breweries around town.

Elle, the play based on dg’s novel, just opened in Vancouver last night at the Firehall Arts Centre after a two-week run in Waterford, Ontario. I was there. I have more to say but am processing. I saw the play several times last year when it premiered at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto. It was stunning then, better now. Mesmerizing, magical, mythic. Severn Thompson looks eight feet tall on stage. Subtle changes in the script and staging and music have clarified and strengthened the production.

But here is what The Georgia Straight had to say — more anon.

dg

It’s been almost 500 years since Marguerite de la Rocque de Roberval, a French noblewoman, was abandoned by her colonizer uncle, Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval, off the coast of Newfoundland. Her crime? Being a wild woman—the kind of wanton lady who dared take a lover on a transatlantic journey in 1542.

Her story of survival became the stuff of legend, and has inspired numerous artists over the years, including Canadian writer Douglas Glover. His book, Elle, a fictionalized account of de la Rocque de Roberval’s time marooned on the so-called Isle of Demons, won a Governor General’s Award, and it’s also the basis of Severn Thompson’s Dora Award–winning stage adaptation of the same name.

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

More exciting news about Elle, the play (based in my novel Elle). If you have been tracking this you are aware that Severn Thompson and Theatre Passe Muraille are taking the play on tour this winter (tour details here). But it’s just been announced that this tour will actually start with performances in my home town of Waterford, Ontario, at the Old Town Hall Theatre, under the aegis of the most charming artistic director ever, Claire Senko (passionate, fierce, scarily competent, friend of Fred Eaglesmith).

I went over to meet Claire Friday afternoon and wander around the place. All strangely familiar because I grew up just outside of town, and once even strummed a guitar with my brother’s band during a rehearsal on the theatre stage in the early 70s.

There will be performances on January 26, 27, 28 and 29, and on February 2, 3, and 4.

There will be an opening night champagne gala and a talkback session with the playwright and actress Severn Thompson and Theatre Passe Muraille’s artistic director Andy McKim (who fed me incredibly intelligent questions about the novel and play when we did an onstage interview together last January).

And closing night (February 5, Saturday) there will be ANOTHER! champagne gala and a talkback session with me after the show. (Amber Homeniuk will be the facilitator, as they call it.)

dg

This video slideshow was produced by an old friend, Alison Bell. (Her brother Ian Bell has appeared in the magazine.)

The Firehall Arts Centre in Vancouver has announced its 2016/17 season, and Elle, the play adapted from dg’s novel by Severn Thompson, will be there.

From Toronto, Theatre Passe Muraille’s Dora Moore Award nominated ELLE, adapted from Douglas Glover’s award-winning novel, tells the story of a French noblewoman abandoned on the Isle of Demons (off the coast of Newfoundland) in 1542.

Severn Thompson in Elle

Severn Thompson in Elle

Severn Thompson’s stage adaptation of my novel Elle is on the short list for a Dora Award in the Outstanding New Play category. The Doras are given out by the Toronto Alliance for the Performing Arts.

Read the Globe and Mail announcement @The Doras 2016: The best in Toronto theatre have a distinctly Canadian flavour.

dg

.

.

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

Exciting news about Elle, the play, (um, you know, based in my novel Elle) is beginning to emerge. Even when I was in Toronto for the world premiere in January, there were quiet whispers about taking the play on tour. Very sotto voce because theatres are a difficult market; they schedule far in advance and prefer their own productions (I was told). But Prairie Theatre Exchange in Winnipeg just announced their 2016-2017 season and Elle is going to be there. And Severn Thompson tells me other productions are in the conversation stage.

dg

A historic play set before Canada was a country, Elle (Feb. 22-March 12) is a sesquicentennial-ready adaptation of a novel by Douglas Glover mostly set in the year 1542. It follows an unmanageable French noblewoman named Marguerite de Roberval who’s sent to the wilds of the New World in Jacques Cartier’s time and abandoned on the Isle of Demons (now known as Hospital Island, off the coast of Newfoundland) by her uncle. Actress Severn Thompson both adapted and stars in the play, which played earlier this year at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto.

“It’s a great story of her survival,” says Metcalfe. “In the usual literary Canadian narrative, people come over and the harshness of the land is tamed and the beauty is discovered. But she doesn’t tame the land, she learns to live inside it. It takes the usual Canadian narrative of our colonization of the land and actually flips it on its head.”

Here’s the Theatre Passe Muraille onstage interview with Douglas Glover, who wrote the book (Elle) on which the stage play (Elle) by Severn Thompson is based. Andy McKim, artistic director at TPM, is a really intelligent and genial interlocutor (there were three pages of lovely questions of which he only managed to ask a handful). The event was billed as “Eggrolls with Andy” and there were, in fact, eggrolls. This was on the evening of January 20, just before the main performance. The location is the little cabaret stage in the bar on the balcony above the stage at TPM. The pictures were taken by the poet Amber Homeniuk, who has appeared before on these pages. She managed to capture some of dg’s more expressive moments.

The sound file is below the images.

I almost missed this one from yesterday. Actually, a good review of Severn Thompson’s performance. Here’s a teaser. Click the link below for the rest.

Severn Thompson, who adapted the play from the original novel by Douglas Glover and plays the role of Elle, is absolutely captivating. In what is essentially a one-woman show, minus about ten minutes, Thompson holds the audience’s attention in a vice grip with her precision, depth and hilarity. Her script it beautifully poetic, and she is a master of its delivery. Through her words and conviction, she creates a landscape and characters that were as vivid and clear as if they had been on stage with her.

Read the rest at Mooney on theatre.

Another review. This one at Torontoist. Here’s a taste:

For a full-blooded heroine with courage, resourcefulness, and a healthy libido to match any debauched Victorian gentleman, look no further than Elle at Theatre Passe Muraille. Actress-playwright Severn Thompson’s rousing adaptation of Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel finds her embodying the legendary Marguerite de La Rocque de Roberval, the young French aristocrat who was marooned on the fabled Isle of Demons off the coast of Newfoundland in 1542 and lived to tell the tale.

Glover’s conception of Marguerite is of a “headstrong girl”—and a bawdy one, too. When we first meet her, she’s aboard her uncle’s ship, having vigorous sex with her seasick tennis-player boyfriend as a means of distracting herself from a horrendous toothache. It’s one helluva’ opening scene—hilarious, erotic, and disgusting all at the same time.

Read the rest at Torontoist.

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

State the obvious. Elle, the novel, and Elle, the play, are distinct works of art. They are radically different forms; we have different expectations. The novel’s more than 200 pages of text suck down to perhaps 40-45 pages of script. This is necessary for the transformation into a play, a necessity and a problem for the playwright in terms of selection, but it’s not something the novelist mourns because, of course, the novel remains, fully in tact, over there on the book shelf.

In brute terms, a lot of the novel disappears. What disappears? The whole sequence of events that occurs after Elle’s return to France is gone. That means Rabelais is gone and the joke about Elle inventing the modern novel. Comes Winter, the native girl brought to France by Jacques Cartier, also disappears. Her tragic story is a dystopian inversion of Elle’s own adventure in Canada. Also gone is the frame device of the one-eyed child-stealing man and the novel’s contemporary tail with the Elle-like young woman on the beach at Sept-Iles with her older lover. These characters and devices are meant to extend the myth and the story of Elle into a larger, more mysterious cosmic rhythm beyond history. The novel is built around a complex set of themes loosely implied in words and oppositions like transformation, literary/orality, translation, New World/Land of the Dead, the invention of printing, colonization/love, and so on. Very little of this survives in the play except in stray phrases or references. Also missing from the play are the details of Roberval’s own failed colony upriver from Elle, pages and pages reduced to a few phrases and the mention of the colony’s failure. What survives in the play is a reduced set of events, a roughly similar sequence of action from Elle’s arrival in Canada to her rescue and departure for France and then, of course, Roberval’s murder in a Paris cemetery years later. The play focuses on Elle’s time in Canada and, in plot terms, becomes more of a female adventure story, Elle as Robinson Crusoe, than the novel is. Conversely, also in brute terms, a lot of the text of the play, the words, come straight from the novel. If you imagine a Venn diagram of the novel and the play, they would overlap at these points. After that, they diverge.

I say this not to diminish the play but to be clear about differences. You don’t want to make the mistake of expecting the play to replicate the novel precisely. I have listed some of the novel elements that didn’t make it into the play, but Severn Thompson’s Elle is an enactment, a presence, with a different structure and tool set, different intentions. It has actors, set, sound, lighting and a reactive audience, all in the same three-dimensional space. A novel is pure text; a play has a physicality that bleeds into the plastic arts so that on stage, moment by moment, you’re presented with tableaux or pictures that have a physical beauty. The presentation at Theatre Passe Muraille has an amazing set, starting with the what the director Christine Brubaker calls “the claw,” a metal and papier mache structure at the back of the stage that looks like the ribs of shipwreck or a dead animal or the back of a cave or the edge of a forest. It also feels like a hand, cradling the characters on the stage in front of it. This is the magic of theatre. The claw is an abstraction that changes with light, verbal context, character action, and, above all, the audience’s imagination.

Besides the claw, there’s the sheet. Oh, wonder of abstraction and efficiency. Severn and Christine needed a bear onstage and a woman changing into a bear and a way to imply that the actors are entering the world of dream. If this were a movie, there would be an actual bear. The sheet is a miraculous rectangle of cloth of indeterminate but changing colour that seems stretchy and drops into gorgeous folds. It’s a sail, Richard falling into the ocean, a robe, a tent, a flag, a hut, a fire, a bear, a sign of dream, and the face of transformation when Elle changes into a bear. There are some stunning moments with this sheet, which is sometimes on the stage floor, sometimes woven into the arms of the claw, sometimes suspended on hooks over the stage, and so on. When the white bear falls upon Elle and dies, it’s the sheet. It’s eerie how quickly the audience gets the implication, a lovely bit of theatre and timing. When the bear woman cures Elle and she drifts into a dream state, Severn the actress has her arms inside the sheet which, pulled from behind by Jonathan Fisher, the second actor on stage, creates a stunning abstract idea of a woman with golden wings. And, of course, when Elle changes into a bear, she’s draped in the sheet, again pulled from behind, so that the human face is suggested but is also bearish. She changes into a bear just by having the sheet pulled against her face and body.

There is deliberate anachronism in the play just as there is in the novel but enacted quite differently. Itslk is an Inuit hunter in Elle, the novel. He presents the intersection of European colonization and the myth/culture of native Canada. In the play, his role is expanded. Jonathan Fisher has a desk and sound board and a microphone and a guitar set up off to one side of the stage. Through the play he makes music, sings a native song, does a throat singing loop, plays the guitar, etc. He’s a contemporary native artist/musician watching the play and participating in the play and, at the appropriate moment, he comes to the centre of the stage and plays the part of Itslk. Again, theatre is physical. In the same moment, Elle is onstage speaking her lines (having sex with Richard, pleading with her uncle, crooning over her dying baby) AND the contemporary native is present just a few feet to the side with an electric guitar and a soundboard. The effect in a theatre is difficult to parse precisely because, in the audience, you are aware of the juxtaposition but at any given moment the imagination is engaged with Elle or the line. The lighting focuses you. It’s a mechanism of audience manipulation that seems marvelous to me. And, of course, there are multiple message loops: Jonathan Fisher is an actor but also an Anishinaabe musician. Also in real life he is a member of the bear clan. And he delivers one of the lines that does depart significantly from the thematics of the novel. This occurs when he is reciting the story of his mythic quest/hunt for the white bear, a quest that Elle disrupts by her presence (one of the crucial metaphors of the novel is the moment when Elle’s European story collides with Itslk’s mythic quest and destroys it). In the novel Itslk is aware, sadly and tragically, that the disruption of his story means the ultimate disruption of his culture, a moment that cannot be redeemed. In the play, Severn Thompson gives Jonathan’s Itslk a more hopeful line about the bear returning, the myth world coming back (in other words), which is a nod to the contemporary resurgence of native of culture. The novel wants the reader to dwell in sadness; the play wants to leave some hope. That aside, there is clear a moment of delight when Itslk appears. You can feel the audience shift. It’s a daring and brilliant invention, this Jonathan Fisher/Itslk character. And he gets to deliver some very funny lines, bring back the dead dog, bring back the tennis ball, and deliver the thematic legend. (It’s fascinating watching audience, BTW. When Elle throws the ball off the ship and Leon, the dog, apparently dies, the audience turns against her, faces go suddenly glum. But when we hear the dog bark off stage, glimmerings of recognition appear. And there is a wondrous delight when Itslk produces the lost tennis ball — for me, this is a bit like watching the readers reading my novel.)

Lighting, sound. You deeply enjoy the effects. The framing of the tableaux on stage and with lighting creates a monumental feeling, creates focus, creates shadow and transformation. Some images are spectacular. For example, the moment when Elle/Severn falls through the ice. Suddenly she’s illuminated by a bright filtered light from above, a column of light, that imitates the flickering, shadowy feel of being under water while the actress mimes a person drifting down. There is more of this than I can describe here. And in all these moments you see the differences in the kinds of works of art. Novel. Play. (And film, if you think about it — the play is so much a series of abstractions demanding audience interaction whereas in a movie there would be much more of the real, a real ship, a real island, a real bear. A film more often than not will try to leave less to the imagination than a play or a novel.)

A play has actors, not to be left out. Severn Thompson loved the novel Elle and saw a place for herself in it, and she is a spectacular actress. On stage every fibre of muscle is engaged in action. Her body is an instrument. She is amazing to watch. We are so used to movie and TV acting, which is mostly minimalist acting from the eyebrows to the chin (actually, on TV acting is mostly a minimal movement of the lips in speaking). The intensity of a stage play is astonishing. I saw three performances and the best audience was the third night which had an ASL component and a large number of deaf people in the audience. ASL is, of course, an enactment of language. Deaf people communicate with actions and they are acutely tuned into the physicality, the presence of the speaker. You could almost feel their attentiveness to Severn’s every move. In stature, she is a diminutive woman; on stage she is monumental and heroic (also very comic, sometimes pathetic, always passionate, exploding with energy). The lighting keeps trapping the gestures, like a series of still photographs, and they are gorgeously expressive. She’s also just a wonderful mime. With a gesture and a hanging of the head, she inhabits bearishness. She knows how a body looks drifting in the ocean. She has so much to work with in the play from lust (gorgeously funny sex scene early on, also a scene in the novel), rapture, resignation, pathos, rage, animal transformation, flirtation, and love to childbirth and the death of the child. It’s a huge part for an actress, a dream role, I would think. And Severn runs with it. Extravagantly and joyfully. I wrote the book, and I was still misting up when Emmanuel dies in her arms. Even the third time I saw it.

What else? Too much to think of. A note on structure. The novel has some little thematic pre-texts, then the frame with the one-eyed man, then the sex scene on shipboard. What the play does instead is quite fascinating. It actually opens with what you might call an overture, a montage of moments (tableaux accompanied by gong-like sound effects and flashes of light) that in fact presage the action of the whole play in gesture alone. The bear is the there, the death of the general, the death of the baby. Just a gorgeous piece of structure. Then the frame: Elle in Paris, by the cemetery, catching sight of the general, Roberval, her uncle in the gloomy street and starting to tell her story. Then the story begins, on shipboard, sex with Richard. Fleetingly, Elle steps back into the storytelling moment, once or twice, just enough to establish the frame and story together, and then we are off. We return to the frame scene at the very end of the play (these transitions beautifully indicated by a repetition of gesture, key language, also a slight costume change and a jug of wine) and thence to the final confrontation with Roberval. Throughout there are beautiful recursions, language, shape and gesture. The “headstrong girl” phrase from the novel. The shape and presence of bearishness (even Jonathan Fisher, with his fur vest, sometimes hulks like a bear). The cradling of the baby Emmanuel (at one point, again, Fisher is back behind the claw, apparently cradling a baby in his arms). It’s also interesting the way the play is text heavy through the scenes up to and including the arrival of Itslk. When he leaves and after the birth and death of the baby, the play leans more and more heavily on image. Itslk’s presence effectively introduces the native element and begins to educate Elle in the epic traditions of the new world (she is already steeped in her own epic traditions). The death of the baby and the advent of the bear woman (and her symbolic rebirth in the ocean) bring Elle into the world of dream and dream and image subsequently drive the remainder of the play, which, here, takes on a quality reminiscent of German Expressionist theatre. These are structural effects, small and large, that you notice upon revisiting the play, and you begin to appreciate the amazing physical inventiveness of theatre.

When I go to a play, I desire a total experience: intelligent interaction with characters/actors on the stage, magical and surprising effects, emotional engagement, language. I got what I wanted when I saw Severn Thompson at Theatre Passe Muraille. I wrote the book, I knew the lines, but I was still surprised and entranced. It was delightful still on the second and third viewing; I saw more, of course, and appreciated the artistry more (and was able to peek at the audience). If you can, go more than once. It’s revelatory. First reviews of the play kept mentioning that awful movie The Revenant (which, in my head, I keep referring to as The Ruminant). That is a completely wrong-headed response based on the most superficial resemblances (wilderness, survival, bear, revenge). Elle (both play and novel) is about first contact, the tremendous collision of European and native cultures, it is about an act that is continuous and ongoing, a conversation between our cultures. Because she is a woman (and a reader), Elle is the most apt and available of the Europeans for transformation. She and Itslk are paired cultural receptors; they know what is going on, the vast, tragic pageant. The Ruminant is a movie with its dumbed-down realism and a pop-Nietzschean thematic that’s very appealing to commercial audiences. It’s not the same thing at all.

—dg

Saw the play for the last time last night then closed the Epicure with Jonathan Fisher, the excellent Anishinaabe actor who plays Itslk, with audience members coming up to the table and chatting to us. A most pleasant way to pass the time.

Here’s another review, somewhat more thoughtful and appreciative of Severn as an actress.

dg

The virtue of Glover’s novel and of Thompson’s adaptation is its satire. When Elle is rescued she notes that Portuguese and Basque fishermen have been coming to Canada long before the French “discovered” it and claimed it for their own. That Elle survives longer in the wilderness than the French government-supported colony is itself a critique of colonists’ inability to adapt and learn from their surroundings. In its anti-male satire, Elle may call herself “frivolous” but her tennis-playing lover is hopelessly impractical and is the first to die. In ints religious satire, Elle, once a fervent Catholic, begins praying to both her god and the natives’ and finally to none.

The role that Elle provides is a juicy one for Thompson and ideally suited to her strengths. Her wry delivery makes the satire all the more trenchant. Her ability to convey a character’s strength beneath her own view of herself as vulnerable is perfect for Elle’s situation. Thompson has always been an insightful interpreter of words, but here she has a chance to display her equally superlative skills at mime and physical theatre. The Elle she creates changes before us from a self-centred society-oriented aristocrat to simply a lone human being with the one simple wish to survive.

Jonathan Fisher, who primarily adds live guitar music to Lyon Smith’s highly effective soundscape, is a taciturn, self-contained Itslk, welcome as an unromanticized First Nations character. His presence in what it otherwise a one-woman show is important for embodying the show’s critique against the European colonization of the New World as if it were not already inhabited. Physically, the playing area already is inhabited before Elle becomes aware of it.

Designer Jennifer Goodman has reconfigured Theatre Passe Muraille’s Mainspace into a narrow thrust stage bringing Thompson very close to the audience, the peninsular stage helping to depict both the isolation of the ship and later the isolation of the island. Goodman’s set is a giant bony structure that looks very much like the skeleton of left hand or left paw threatening those on stage. Yet, depending on the lighting, it can also look like the inside of the cave where Elle seeks refuge or the ribs of the hut Itslk helps to build. Brubaker makes very imaginative use of a large piece of cloth that can be a sail, a tent or, most remarkably, the skin of the bear into which Elle transforms herself.

When Severn Thompson read the novel Elle four years ago she had no idea that this story would capture her imagination for years to come. The Governor General’s Award-winning novel written by Douglas Glover is based on the true story of Marguerite de Roberval. Marguerite, along with her lover and nurse, were marooned by her uncle the Sieur de Roberval on the Isle of Demons in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Thompson spent the last three years adapting and workshopping Elle before bringing it to Theatre Passe Muraille. “It struck me as so refreshing to find a female voice from a time I had heard very little about, in the very early days of the explorers in the mid 1500’s,” says Thompson. “I felt very close to her [the character]. The story crossed 500 years very easily for me. It brought the past to the present.”

Another review that’s positive despite not being able to keep The Revenant out of the lead. Jesus wept. 🙂

d

The biggest story in the film world right now includes hypothermia, parenthood, bear attacks and Leonardo DiCaprio’s potential first Oscar win in Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s The Revenant. Who knew its companion piece would be revealed at Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille, and that Hollywood’s favourite movie would share so many similarities with a story foundational to the creation of Canada.

In Elle, which had its world premiere this week at Passe Muraille directed by Christine Brubaker, writer and actor Severn Thompson adapts Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel of the same name into a mostly solo performance that weaves feminism, survival instincts, colonialism and magic realism together.

Here’s another review by a man who seems to think everything would be better as a movie and reviews the play as if it were a text and not a series of scenes and tableau-like images that, as the play wears on, remind you more of German Expressionist theatre than what he inappropriately calls “magic realism.” He makes no mention of the theatricality of the play. His descriptive vocabulary is minimal. “Tense” — what does that mean? And he obviously hasn’t read the novel. This is typical of a certain withered Toronto provincialism that equates the Academy Awards with the acme of our culture and thinks that by mentioning them you mark yourself as hip and in the know. 🙂

What can you expect from a newspaper that so badly read the mood of the country as to endorse Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party in the last election? And we all know how that went down.

dg

A white person left for dead in the North American wilderness in the days of conquest and colonization. A highly symbolic encounter with a bear – and local indigenous peoples. An epic journey of survival across a frozen landscape seeking revenge.

No, it’s not The Revenant, the Alejandro Iñárritu film leading this year’s Oscar nominations. It’s Elle, Douglas Glover’s 2003 Governor-General’s Award-winning novel – now transformed into an occasionally tense, but frequently funny play by the actress Severn Thompson.

Read the rest at The Globe and Mail.

Here’s a review excerpt.

In his program note, Andy McKim, Artistic Director of Theatre Passe Muraille, references author Douglas Glover (who wrote the book on which the play is based): “It was remarkable that she (Elle) survived by herself when the large expedition brought to colonize Canada by (her uncle) and Jacques Cartier couldn’t succeed. (Perhaps) her motives were somehow purer, that she was closer in her attitudes to what we might call the forces of life, and this allowed her also to be more open to native culture.” Or it could just simply be that Marguerite de Roberval (Elle) was one resourceful woman who knew how to suck it up, use what was available to her and embrace and respect her surroundings and survive.

Severn Thompson has adapted Douglas Glover’s book so that it lives on the stage. The language is eloquent and poetic. At one point Elle refers to “endless misty vistas.” I certainly don’t mind spending time in a theatre if I can listen to poetic lines like that, delivered with as much passion and life as Severn Thompson imbues in Elle.

Read the rest @The Slotkin Letter

So, okay, first night. Spectacular, magical. Standing ovation, curtain calls. A transformation of my novel for sure. But Severn Thompson was born to play Elle, the headstrong girl. Funny, passionate, poignant. A bravura performance, a woman holding us mesmerized for 90 minutes. Stunning visual effects, but theatre, cheap computer generated effects. The moment when she falls through the ice, amazing lighting effects, a column of light flickering as if water. Transforming into a bear using a lengthy sheet of gold material pulled against her body, her raised hands clawing against it (just amazing what theatre people can do with a sheet). Terribly poignant opening up of the play with the entrance of Jonathan Fisher as Itslk. Scene after scene, image after image. The scene where the baby Emmanuel dies. OMG. I don’t think many authors get a chance to see someone make another work of art of their own creation. And fewer still can be so pleased and moved and feel that such homage has been paid. I am going to bed now. Tomorrow I will resume my habitual sardonic mask. But tonight I was moved. Go see the play if you can.

d