Donald Breckenridge

Donald Breckenridge

Herewith, my introduction to Donald Breckenridge’s extraordinary new novel And Then just out with Black Sparrow, the venerable experimental/indie press now an imprint of David R. Godine in Boston. The introduction is included in the book and is reprinted here by agreement with Breckenridge and Black Sparrow/Godine. This isn’t a review; it’s an elucidation of the genius of form.

—dg

.

“We walk about, amid the destinies of our world-existence, encompassed by dim but ever present Memories of a Destiny more vast — very distant in the bygone time, and infinitely awful.” Poe, Eureka

Donald Breckenridge is a pointillist, constructing scene after scene with precise details of dialogue and gesture, each tiny in itself, possibly mundane, but accumulating astonishing power and bleak complexity. His language is matter of fact, the unsentimental plain style used subtly and flexibly. The only apparent artfulness is in the unconventional punctuation and, sometimes, the way the dialogue breaks up the narrative sentences. His settings are Carverish, bleak and constrained; his characters are the stubborn, alienated authors of their own melancholy fates; they persist in a panoply of failed habits and attitudes, gestures of a wounded self they refuse to give up because it is their own, a refusal that is by turns defiant, sordid, heroic, grotesque, and tragic.

But this novel’s triumph is in its rich architecture, its surprising splicing of genre and quotation, its skillfully fractured chronology, and the deft juxtaposition of alternating story lines. The result of this combinatorial panache is to create an arena of systemic implication, in which the sum is greater than the parts. Nothing here is what you expect; in fact, some of this text is nearly indescribable in terms of genre and form. What do you call a piece of fiction that is a narrative transcription of a real movie that is itself a fiction? Answer: Don’t even try. It’s a logical wormhole. It will turn your brain inside-out like a sock.

I will elucidate: And Then is, like most novels, a story about a character. Let’s say a nondescript loser robs a mom and pop store in some out of the way town and gives the money to his girlfriend so she can escape the mean and derelict provincial life she is destined for. She heads to New York with the cash, finds an apartment share, and has a love affair with a photographer, but the police (somewhere) are after her, and she falls among bad companions under the sign of hard drugs, who love her for her money. When that stake runs out, so does her string, and she disappears, probably dead, floating in the river.

But Breckenridge, the symphonic composer, takes this narrative theme, his melody, and works magic upon it by adding a half-dozen further elements.

1) A second, parallel plot involving a young male student who, a dozen years later, agrees to cat sit for one of his professors away on sabbatical. In the apartment he discovers the photograph of a beautiful woman, his professor’s mysterious former lover and/or roommate, a woman who simply disappeared. The student obsesses on the woman in the photograph; he becomes a sleuth, collecting stray bits of information about her. He finally tracks down the photographer who took the picture. But no one knows what became of her.

These two plots, the young woman plot and the student plot, leapfrog each other in the text, fragmented and uncanny. At a certain point the young woman, apparently waking from a drug stupor (only she is dead), finds her way back to the apartment, ascending the stairs just as the young student is descending. At the climactic moment, he feels her ghost passing through him.

2) An epigraph from Ionesco’s Present Past Past Present, an important influence for Breckenridge who takes epigraphs for all his novels from this text. The passage presents a character unfree, chained down, but conscious that he has the key to freedom, which he hardly ever uses.

3) An overture, or introductory passage, that consists of a prose transcription/narrative summary of Jean Rouch’s film Gare du Nord (1995, one of six short films by leading New Wave directors under the title Paris Vu Par). The film splits into two parts. The first follows a young married couple quarreling over the dissolution of their relationship; they are fed up with each other, disappointed in their mistakes, tired of their lives. In the second half of the film, the wife meets a handsome, brooding fellow who offers transcendence, offers her the chance to run away to a life of adventure. But she’s too bourgeois, timid, and polite to take him up. His response is to climb the bars of a railway bridge and jump to his death.

But what is going on? A novel disguised as a summary of a film? A quotation, as it were? A meta-commentary, or a work of art based on a work of art or in dialogue with a work of art? And the story itself is iconic, presenting the enormous ennui of modern life in the pressure cooker of a young marriage. But then the young man in the suit offers liberation. Is he a con, is he the devil, is he an angel? And the girl can’t contemplate running away from the life that is grinding her down. She hurries back into the trap. She doesn’t trust freedom — well, who would trust a man you had just met, who talks crazily about adventure, who looks too good in that suit? What is she going to do now? The message loop Breckenridge creates is convoluted and mysterious and yet firmly within a novel-writing tradition starting with Cervantes who, after all, wrote a great novel about a man trying to imitate another book.

4 & 5) The last quarter of the novel text is actually Donald Breckenridge’s brutal, sad memoir of his father dying: stark and beautiful and full of our common humanity; pity, love, kindness, stubbornness, squalor and valor. Here again there are two narratives: one works back and forth over the story of a life, two lives, father and son, and the father’s declining days; the other, more mysterious, follows Breckenridge to a diner, the subway, the train station. We get detailed accounts of conversations with the diner owner. We oscillate between donuts and staph infections, but by the genius of construction and understatement, horror and hopelessness accumulate. The word “love” isn’t thrown around, but the son patiently bandaging and dabbing medication on those awful sores tells you more than words. You are fascinated and cannot turn away.

Curiously, embedded in the memoir we find a scene in which Breckenridge tells his father about the suicide of a woman who lived in an apartment above him and how, he is sure, that one day he encountered her ghost in the stairwell. (The reader himself encounters a frisson of combinatorial delight.)

6) But even more curiously, embedded in the memoir we find also a few paragraphs in italics quoted from Théophile Gautier’s romantic horror story “The Tourist” (originally published as “Arria Marcella: A Souvenir of Pompeii” in 1852), a ghost story of sorts, in which a young traveler becomes obsessed with a woman’s figure preserved in the ash of Pompeii only to find himself translated that night to ancient Pompeii where he falls in love with the very woman. The story has the air of Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” or Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” The young traveler, sent back to his own time without the ghostly lover, never falls in love again, never fully engages with life.

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

.

And Then is beautiful, artful, an elaborated system of repetitions, motifs and juxtaposed narratives. Without wishing to be reductive, one can say that the three ghost stories relate to the theme of co-presence of temporal periods signaled in the Ionesco quotation, the way the past haunts existence. And they are balanced with three stories of characters who cannot change their behavior when change is the only way to redeem themselves (the young Parisian woman who cannot leave her job and marriage, the girl who runs away to New York with her stash, and Breckenridge’s father who cannot get himself the treatment that would save his life). And these in turn are refracted in three observer stories: the Brooklyn student who falls in love with photo of a missing woman, the youthful traveler in Gautier’s horror story, and Breckenridge watching his father die.

And Then is a contemporary ghost story, full of horror and unremitting melancholy, heir to the romantics, to Gautier and to Poe (yet also, stubbornly unsentimental in affect, reminiscent of the Nouveau Roman), a vastly literate work, engaged in its own conversation with the bookish past. Everything here is doubled and redoubled, echoed, mirrored, and reflected, and the dead do not die. The dead turn into ghosts or memories or words on the page, all of which are the same perhaps, at least in a book. And the effect in this novel is to create a mysterious intimation of a larger reference, a world beyond the book, a teeming yet insensible world that is yet no consolation.

—Douglas Glover

.

.

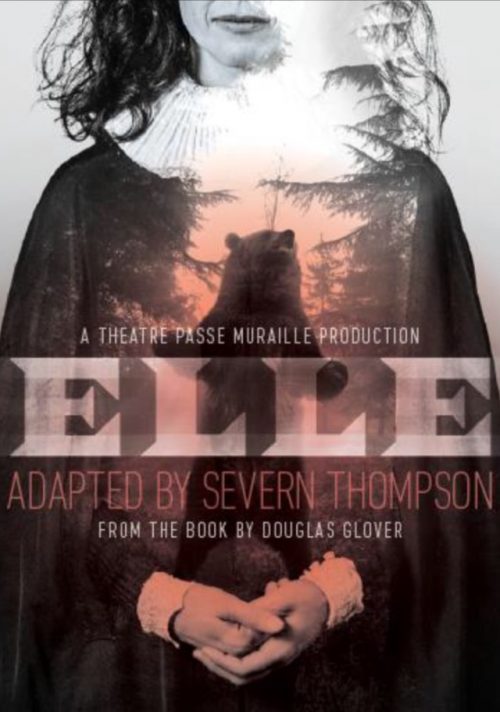

Severn Thompson as Elle

Severn Thompson as Elle