Photo credit by Jonny Griffin.

Photo credit by Jonny Griffin.

The boy’s right leg quivered and he had to lean against the mud-wall of Sarkanda’s house to assess his wounds. He pulled up his pants and looked at the two deep holes, slightly below his skinny calf, where the dog’s canines had sunk in. With the tips of his fingers, he carefully pressed around the wounds and then limped off towards Khala’s house to borrow some salt for dinner. As he walked, he hoped that the rumors were true and that Qatel had been kidnapped and killed. But he worried how he could avoid Shah Wali Sarkanda, his friends, and Qatel too, if the rumors were not correct.

He had not yet turned the corner when the first shot went off. He slowed and looked up at the two startled turtledoves as they hastily flew away from the dead electric lines overhead. In the stale summer afternoon air, the shot sounded like a heavy hammer colliding against a thick sheet of corrugated, rusty metal: lonely, removed, yet lethal. By the time he approached the main street, the shooting had begun to intensify.

He looked around for Qatel; he tried to sneak a peek inside the checkpoint, a small primitive square structure of assembled plastic sandbags with a scanty roof of flattened oil barrel steel. The dog was not there. He glanced under the window of the bakery across the street where Qatel sometimes sought refuge when the heat of the day became unbearable, his tongue sticking out, panting. To his relief the dog had disappeared. “They’ve indeed taken the bastard,” he thought to himself, and felt the beginning of an unmanageable delight.

.

The boy was the youngest of his four siblings, and as the rules of the house dictated, he had to run all the errands. Mother sent him around to the neighbors and relatives to borrow a loaf of bread, the coal-fired pressing iron, a mortar and pestle, a painkiller, a cough syrup bottle, or a big shawl when she needed to step outside the house to attend a funeral or visit her sick and dying acquaintances. When unexpected guests showed up at their door, he had to find and carry plates and silverware and pillows and blankets. He usually brought most of these items from Khala’s, which meant he had to cross the checkpoint and the narrow, unpaved main street. Last week, when Mother needed to go to the funeral of Uncle Khanjan, who was killed by a stray bullet in front of his house, she sent him to borrow Khala’s black leather shoes, and the two militia guys, Sarkanda and Habib Charsi, had urged Qatel to chase him. Under the midday sun, they were sitting against the big whitewashed wall across from the checkpoint, high on Chars, their Kalashnikovs lying by their sides. When the dog charged after him and knocked him to the dirt, they had rolled on the ground, laughing.

.

Now Qatel was missing. Habib, Nasro Puchuq, and Zaman Dashka huddled in the freshly dug trench near the bakery, the dark, wet soil still piled against the bare electricity pole. Zaman manned a long-range Soviet DShK machine gun. He was planting his left knee into the fresh soil of the trench and using his right leg as a support for his right hand as he pulled the trigger. He was the only one who made an effort to aim before he shot, while Habib and Nasro, crouching on either side, fired their Kalashnikovs aimlessly in the general direction of the enemy’s position, a few hundred meters away at the end of the street. Sarkanda didn’t aim either. He was lying flat on his stomach right outside the trench in the middle of the street, his feet bare, the front of his long and loose navy blue perhan-tunban covered in dust. He fired with a maniacal passion, and the hot empty brass casings thrust out and fell by his side, bouncing and clinking.

The boy watched Sarkanda in disbelief. He had always seen him with a foolish smile on his face, but now he looked serious and determined. The boy tried to think why Sarkanda and his friends were fighting and how long the skirmish would last before he could go get the salt. He knew that Mother would straighten him out with the end of the broom if he took longer than usual.

Inside the bakery above the trench three men went about their work. One of them, with a dirty off-white piece of cloth wrapped around his head and covering his mouth and nose, bent down and came back up with a practiced efficiency and rhythm. With his back to the street, he fixed the flattened dough on his rafeda and put it into the oven, not caring the least what was going on outside. Across from him the fat owner of the bakery leaned against the soot-darkened wall, drinking his afternoon tea.

The shopkeepers whose shops were in reach of bullets had stepped outside and now stood in the safety of the whitewashed two-storey building. They talked and laughed, and the pedestrians who were blocked because of the gun fighting joined them. The porter rested in his wheelbarrow, his hands folded under his head, and shyly laughed at the vegetable seller’s silly jokes. The only people who did not participate were the two women covered in big dark shawls who came out of the same alley as the boy. When they saw the shooting, they sat against the wall, a few meters away from the men, in absolute silence.

.

The fighting went on. The boy cupped his ears with the palms of his hands and the shooting was drowned as if in a wind tunnel. As soon as he lifted his hands the sound of gunshots came back, loud and ludicrous. He closed his ears with the tips of his fingers this time and pressed them hard. The sound of war seemed as distant, as unbelievable, as a dream.

It looked as if people had stepped outside of their houses and shops at the first sign of a shallow earthquake, and now that they were out they thought why not catch up with their neighbors. Baba, a shopkeeper in his late fifties, didn’t even bother to leave his shop, an old, red shipping container insulated with a thick layer of mud and straw, right behind where Sarkanda and his friends had dug out the trench. In his impoverished, half-empty shop, he sat deep in thought, perhaps believing there was no way a stray bullet could find its way to him because the door of his shop opened perpendicular to the direction of the bullets of the Panjshiris. Still, he had to leave some room for his ignorance of the laws of physics, the intricacies of geometry, and above all some room for chance, and it made him worry. A bullet might take an inappropriate swerve and enter his shop. Now in the heat of the crossfire there was no way he could get out, so he sat there taking thoughtful sips of his steaming green tea and silently wishing a quick end to the reckless shooting.

The rain-filled clouds hung low, and it had become very hot. The boy leaned against the edge of the big whitewashed wall and looked past Sarkanda and Zaman. At the mouth of Khala’s narrow alley a group of people waited patiently for the shooting to cease. The boy folded his hands behind his back, balanced his weight on both heels, and started to wriggle. Then he stopped and looked down at his big toe sticking out of the tip of his right shoe, dirty and unwashed, exposed to dust and humidity. He tried to work it back into his shoe, but the hole was too generous. So he wiggled his toes and wondered when and where he had lost the lace on the left shoe. He felt a shudder of grief that his only pair of shoes was disintegrating faster than he’d expected. That meant he would have to switch back into hard plastic galoshes that cut the back of his heels and smelled terrible. To fight off this disturbing thought, with the tips of his fingers he took hold of the scanty sleeves of the old, discolored yellow sweater that he was outgrowing fast, and pulled them down. The collar of the sweater overstretched, revealing his scrawny neck and his fragile collarbones.

Then he fixed his gaze on Sarkanda, who still rested on his stomach on the ground, his whole body, particularly his shoulders, a constant tremor. A bullet whizzed past Sarkanda’s ear and hit the dry mud wall behind him. The boy, and the few others, who saw it, let out a cry of bewilderment mixed with a chill thrill. “Da kos khowar shomo to that vagina of your sisters!” Sarkanda gurgled aloud in a raspy voice and jolted forward as if the smell of heated copper and burned sulfur nitrate and the proximity of death fired up his determination. The two women who had been sitting against the wall became uncomfortable, hearing their most private part spoken of openly. The older woman made a failed attempt to swallow her laughter, but her lips puckered. The younger woman maintained a serious look and stared at the ground in front of her feet. The shopkeepers gave out a lighthearted laughter at Sarkanda’s effortless way of saying Kos, but also at the fact that the bullet could have easily smashed his face had it been an inch to the right. “Kam bod Sarkanda ra wardar kadod!” said one man. “Nah, I guess even death avoids that motherfucker. I bet even in hell he would rob people in open daylight and extort money,” responded another.

“Or a pack of cigarettes,” said the porter, adjusting his wheelbarrow.

The bakery owner shifted his weight on his left hip and glanced out the window to see what had happened. The baker put the rafeda down and turned for a quick peek at the street below. As soon as he realized that the moment was gone, he went back to his work.

“They’re wasting ammunition on such useless matters,” said the vegetable seller.

“How did all this begin?” said a bystander, a skinny man, constantly moving his jaws to adjust his dentures.

The boy moved closer to the men to hear what they were talking about.

The vegetable seller paused longer than he should have, trying to look important. “I heard that the Panjshiris kidnapped Qatel,” he finally said.

“Who is Qatel?” asked the man.

“The dog,” the vegetable seller responded.

“Oh, they’re out to kill each other over a dog?” said the man grinding his jaws, his plastic teeth making an empty sound.

“Yeah, these guys sent someone to bring the dog back, but the Panjshiris slapped the messenger in the face and sent him empty handed,” said the vegetable seller, raising his eyebrows and maintaining a faint smile. He was proud to know something that the others didn’t. Although he had said everything there was to be said about the shooting, he couldn’t stop himself, so he continued. “Did you know that Sarkanda had stolen that dog from a house?” He looked at the man with dentures for a reaction, but the man was busy looking at Sarkanda and his friends, who were still shooting relentlessly. The vegetable seller turned towards the boy, hoping he was listening to him. The boy, too, was watching the shooting. So the vegetable seller with a servile look on his face helplessly turned his attention to the fighting.

They all were looking at Sarkanda admitting that he had earned his nickname “the headless,” and they secretly admired his inexorable fearlessness in the face of death, a quality they well knew they didn’t possess. All of a sudden Sarkanda ducked his head. The bullet hit the hard steel in the corner of Baba’s shipping container that stuck out of a thick layer of mud, then rebounded and caught the skinny man above his right knee. “Akhhhh!” was the only sound the man made, and he sat on the ground holding his wounded thigh. The two women looked in the man’s direction, their faces warm with pity. Baba put down his glass of tea on a cooking oil box next to him and stood in his place to assess the situation. That was the maximum movement he allowed himself to make. The fear of getting hit by a stray bullet was tangible now that the man’s thigh started bleeding.

The porter ran with his wheelbarrow to help. The vegetable seller lifted the wounded man and placed him in the wheelbarrow.

The boy’s toes felt numb, especially the one that stuck out of his shoe. He saw the agony on the man’s face, and he noticed that for once the man was not adjusting his dentures, but clenching his jaws and shaking his small head from side to side as he lay on his back, his face pale, his legs dangling off the edges of the wheelbarrow.

“Would the compoder compounder be in his shop?” the porter asked, not particularly directing the question at anyone, but thinking out loud. He hurriedly pushed the wheelbarrow towards the pharmacy, negotiating the bumps, and disappeared into the alley.

.

Nasro and Habib had stopped shooting, their cartridge magazines lay empty, but they stayed low in the trench amidst piles of spent shell casings. The shooting from the other side also died down. Zaman was dissembling his DShK. Every now and then a bullet rang in the air, and Sarkanda fired back. This went on for a couple of minutes as if no one wanted to bear the burden of being the first to accept defeat.

Eventually the shooting ended just as it had begun.

The crowd started crossing the street as soon as they thought it was safe enough. The two women got up. The vegetable seller went back to his shop and started sprinkling water over the fresh vegetables: basil, scallions, spinach, lettuce, radishes, cucumbers, and carrots, neatly organized on big inclined tables.

The boy crossed the street and stood at the mouth of Khala’s alley, his eyes set on the empty casings that lay in and around the trench.

Zaman stood up, and asked Nasro and Habib to help him carry the DShK back to the checkpoint. They carelessly flung their Kalashnikovs onto their shoulders, and each man held and carried one stand of the heavy machine gun. Sarkanda was the last to get up. He held his old, Russian PK by the muzzle and dragged it across the street into the post, and then came back for his sandals that lay face down on the ground.

As soon as Sarkanda went into the checkpoint, the boy rushed to the trench. He took fistfuls of the spent shell casings and fitted them into his pockets hurriedly, his heart racing as if he had struck a gold deposit, but others could come and loot him any minute. Two kids he had not noticed before jumped into the trench beside him. One of them knelt on the wet soil and held the plastic sack, while his friend shoved the empty brass casings with both hands into the bag. Although the boy’s pockets and palms were full, he wanted to pick more. Then he stood there in the middle of the trench calculating how much money he would make from selling the casings in his pockets. The amount seemed insignificant compared to what the two kids would get. He envied them and their bags.

Silently but bitterly he walked out of the trench holding his waist-band and headed to Khala’s house. He knew that he had taken way longer than he should have, and that Mother was waiting for him with the broom in hand, but the jingling sound of the shells in his pockets comforted him.

.

By the time he returned with the salt, life on the main street was back to normal. People stood in the line in front of the bakery to buy fresh bread for dinner. Zaman, Sarkanda, Nasro, and Habib sat in the checkpoint, exhausted yet at peace. They leaned their heads against the sandbags. The dog issue was not settled and the fight would go on, but for now they could enjoy the two joints that went around in the circle.

Across from the checkpoint, the porter scrubbed the blood from his wheelbarrow, and the vegetable seller was pouring water on his hands from a green plastic pitcher. Baba stood next to them holding his cup of tea. They talked, and every now and then they all laughed and shook their heads.

.

The boy turned the corner towards home. He felt the first drop of rain on his bare collarbone. He looked up at the dark clouds and knew it was about to rain hard. He started to run, but his leg felt numb, just where the dog had bit him and where the man had bled. He stumbled, then found his footing, and ran again, limping. The shell casings jingled in his pockets with the sound of empty brass.

— Jamaluddin Aram

x

Jamaluddin Aram is a documentary filmmaker, producer, and short story writer from Kabul. His documentaries My Teacher Is a Shopkeeper (part one, part two) and Unbelievable Journey have been screened in Afghanistan and elsewhere around the world. He is the associate producer of the Academy Award-nominated film Buzkashi Boys. He is currently pursuing a major in English with a concentration in creative writing at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

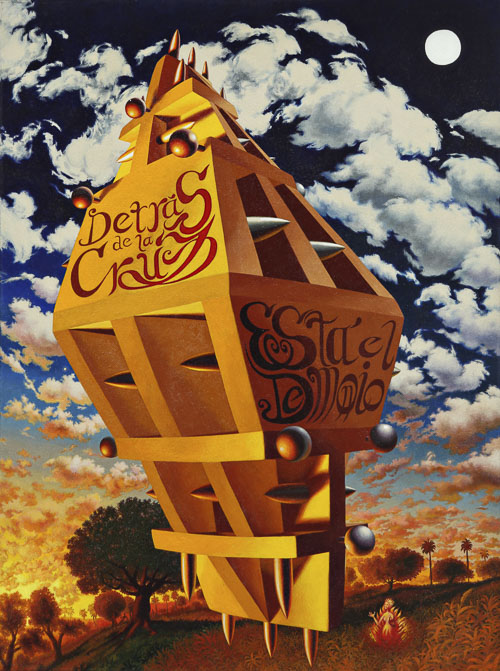

Map of a Utopia

Map of a Utopia