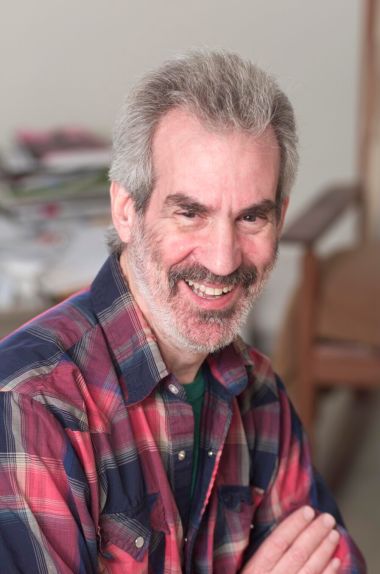

“The Connoisseur of Longing” is a wry, dry, witty story about a man, a writer, who fails to live up to his own press. Mandalstram, late in his career, wins a prize for a little book based on a love affair deep in his youthful past. The jury calls him a “connoisseur of longing,” a phrase that captures his imagination and propels him into a search for meaningful people from his past (wives, daughter, friends). The results are comically catastrophic. Everything Mandalstram remembers is not true. The story is told from Mandalstram’s point of view, deadpan and serious, except, you know, that he is wrong. Right down to the fact that his Holocaust-survivor parents weren’t Jews. This story is excerpted from Dave Margoshes brand new story collection appropriately entitled God Telling A Joke and Other Stories (Oolichan Books, 2014). Dave Margoshes is an old friend from my Saskatchewan days (Fort San, the Qu’Appelle Valley, the Saskatchewan School of the Arts — the memories!). He is one of Canada’s finest short story writers. And in years gone by, when I edited the annual Best Canadian Stories, I included him four times out of the ten collections I put together.

dg

Many of Mandalstram’s books were overlooked by his peers; a few were shortlisted for minor awards, an achievement and honor in itself, but didn’t win. Finally, fairly late in his life, he won a major award for a slim novella, Disconsolate, a delicate love story that was, in fact, a revised version of a story he had written when he was in his twenties. The passion in the prize-winning book, so admired by the jurors, was all from that period of his life, when he had pursued an unrequited love affair with a certain woman from Madrid and had burned with ardour, the sort of ardour only a man in his twenties can experience. But the craft, those tricks of the writing trade which make a story so compelling, was all from that later period of his life, the period of revision, a practice he had mastered. Passion and craft were a happy marriage, and they worked well for Mandalstram. Disconsolate, the jurors wrote, ached with the agony of a spurned lover, exquisitely rendered, and Mandalstram himself, they wrote, was a “poet of the heartbroken, a connoisseur of longing.”

He smiled at that latter phrase—“connoisseur of longing,” which seemed, he thought, to fit him like a well-tailored jacket—and, as he slept restlessly that night in an unfamiliar hotel bed, in Toronto, a city he didn’t particularly like, the words chimed through his dreams like the cream-rich tones of a clavichord. He awoke amused by the possibilities. A publisher might create a Library of Longing, with paperback reprints of all his out-of-print books. The CBC might prepare a reality show, Canada Longs, with chipper Wendy Mesley as host and Mandelstram himself as featured guest. A restaurant might prepare a Menu of Longing, with dishes inspired by plots and character from Mandalstram’s stories. He arose, turned on the electric coffee pot and showered. Then, feeling pampered in the hotel’s fluffy white robe, with a cup of weak coffee by his elbow—oh, how he longed for something stronger!—he sat in sunlight at a small polished marble table—whether true marble or faux he couldn’t tell—and, on creamy hotel stationary, began to make a list. This small pleasure was interrupted by another—the first of several telephone calls from the mass media.

Back in Halifax, where he had lived for the decade since his third marriage failed, he found himself still propelled by the momentum of his unexpected victory. The money that accompanied the prize—more than he would ordinarily earn in two years!—was a godsend, no doubt there, but more important was the boost to his career. It would have been better, far better, to have had this twenty years earlier, fifteen, even ten, but he still had another ten productive years in him, another three, four, maybe five books if he approached them with more discipline than he ordinarily could harness.

He expected the invitations to start rolling in: lectures, interviews, workshops, residencies, festivals, readings of all sorts before all sorts of audiences. He’d had his share of that sort of thing, of course, but never enough to provide more than the most meager of livings. Always, he’d had to teach a class, take on an editing job for someone of lesser talent, even, on occasion, lower himself to the indignities of writing a review or article for the popular press. He looked forward to refusing those routine kinds of offers, to enjoying more of life’s little comforts while, at the same time, being able to devote more time to his own work, which meant he’d have to asses the new opportunities carefully. Perhaps there’d be an unsolicited grant, maybe even a call from one of the agents who hitherto had spurned him. He looked forward to the possible pleasure of telling one particularly nasty agent to fuck herself.

In the meantime, while he awaited these opportunities, he should allow euphoria to propel him into a regimen of inspiration and momentum. The backbreaking, spirit-snagging novel he’d been working on for several years, which had all but defeated him, now seemed manageable, its completion and publication inevitable. He would throw himself into work with a renewed vigour, informed by the sort of passion that had so impressed those jurors. Yes, passion was what had been missing from his latest work; passion, propped up by artful craft, could be his salvation.

But not just yet. His telephone was still ringing, interview requests from reporters and congratulations from friends and—this most delicious—acquaintances who now wished to be friends. Serious work was out of the question with such interruptions. And at any rate, a day or two of diversion, to savour the moment and let its meaning sink in, would do him good. A perverse, compulsive pleasure, but pleasure nonetheless, like tonguing a sore tooth.

Mandalstram consulted the internet and, fortified by a cup of espresso, telephoned his first wife, who lived now in Milan, where she had a thriving practice as a designer of high fashion, knowing full well what sort of response he was likely to induce. They hadn’t spoken in over twenty years, and that only as the result of accident, but he had kept up with her comings and doings, another perverse pleasure.

“Louella,” he announced, “it’s Franklin.”

“Calling to gloat?” Her voice sounded older, leathery, but with all of its old bite. To his disappointment, she didn’t seem at all surprised to be hearing from him.

“Gloat?”

“I read about your triumph.”

“Hardly that, my dear.”

“Considering what came before it….”

“Well, yes. And thank you for the implied congratulations. But gloat, no, that isn’t what I’ve called about.”

“And that is?”

He hesitated, betraying himself. “To apologize. I am sorry. For…”

“Oh, fuck you, Franklin.” She hung up.

Mandalstram was stunned by the sharpness of her response, though it did not extend far beyond the realm of what he had considered possible—he certainly had known she wouldn’t be pleased to hear from him, regardless of the circumstances. They had both been young and inexperienced in their brief time together—she had come into his life during that bleak period when he was nursing the wounds inflicted on his heart by the Spanish woman—and it had ended badly, on so sour a note that a stain on the abilities of both of them to form healthy relationships had remained for some time, only gradually fading. As to be expected, Mandalstram had blamed Louella, she had blamed him. Over time, he had come to realize that probably neither was to blame, that they had both merely been caught up in forces beyond their control. Louella, apparently, had not yet attained that stage of perspective and clarity.

Having worked his way through that brief analysis, Mandalstram broke into a smile and brewed himself another cup of strong coffee—this was a morning for indulgence. Although the call had not gone as he’d hoped, he still drew grim satisfaction from it. He made a mental check on the list he carried in his head, a duplicate of the one he’d drawn up in Toronto.

*

Mandalstram’s parents had been Holocaust survivors who were loathe to talk about their past. He was a bright, inquisitive child, with a fertile imagination, an only child often left to his own devices, and though his parents provided few clues, he grew up surmising that they were Jewish. Indeed, they attended a Reform synagogue and his father was a reliable contributor to the minion. It was only in his teenaged years that he learned they weren’t Jews. Berliners, intellectuals, journalists the both of them, they were Communists persecuted for their politics, not for race or faith. Mandalstram’s father was an atheist, whose own parents had been Catholic farmers; but his mother had been raised a Lutheran and came from a well respected middle-class family of lawyers and teachers, good Aryan stock. True, the name Mandalstram did smack of Jewry, though it was in fact solidly Germanic, but had not his father and mother both written inflammatory articles attacking National Socialism in a suspect periodical, they would likely have gone through that terrible period of history unscathed. At the very least, they would have been able to escape with body and conscience intact.

Instead, they rejected several opportunities, first to emigrate in orderly fashion, later to flee in haste, and were rounded up and sent in cattle cars along with hundreds of fellow travelers to Bergen-Belsen, where, somehow, they managed to survive.

Prying even these minimal details out of his parents had been something of an achievement for the high-school-and-college-aged Mandalstram, so he never did learn anything of their lives in captivity, the bargains they may have been forced to enter into.

At any rate, after the war, the shattered couple was able, finally, to emigrate to the United States, where they attempted to rebuild their lives, taking up residence in a largely Jewish neighbourhood in the Bronx and devoting themselves—or so it seemed later to their son—to a quiet pursuit of redemption, not that they were in need of any. It was perhaps inevitable that these survivors of Hitler’s death camps should seek the comforting company of other survivors, the teenaged Mandalstram conjectured; if not inevitable, it had at least worked out well. The elder Mandalstrams lived a quiet, humdrum existence, working as minor government functionaries—his mother as a clerk at the borough hall’s property tax department, his father with the post office. As a child, teenager and young man, Mandalstram, of course, had chafed against the restraints of his parents’ orderly lives, had rebelled against it, but in time he’d come to understand it. As a refugee from the U.S. to Canada during the inflammatory years of the Vietnamese war, he found himself replicating their steps to a certain extent.

Mandalstram’s parent were now dead. He had no living relatives on this side of the Atlantic, at least none he was aware of, and no knowledge of any relatives on the other side. That was one area of his past that was immune, then, from his present preoccupation. Nor could he think of any offence he might have caused any of the millions of people involved in that sordid chapter of history. No, if there was an apology owed, it certainly wasn’t from him.

*

Mandalstram had no idea where his second wife, Margarita, was now. He mined his address book and, again, the internet for clues, without success, and made a few calls, but the mutual friends he consulted either did not know her whereabouts or were disinclined to reveal them to him. His call to Arthur Behrens, a friend from those days, an art school classmate of Margarita’s, who had climbed through the ranks of the federal cultural bureaucracy and was now an assistant deputy minister, was typical.

“I don’t think she would want to hear from you, Franklin—even if I knew where she was.”

“Which you really don’t, I presume?”

“Of course.”

“Well, you said she wouldn’t want to hear from me. I thought perhaps…”

“No, I’m not lying. If I did know, I’d say so, but wouldn’t tell you where. I’d be willing to pass along a message, that’s all. But as I said, I don’t…”

“So what you’re willing or not willing to do is irrelevant,” Mandalstram interrupted.

“Yes, but your ill-temper does little to engender sympathy, quite frankly. Congratulations again on your prize. Now goodbye.”

Mandalstram attempted to apologize for his impatience, but Behrens had already hung up. A few more calls that were no more productive only served to abrade his nerves and cause him to reappraise his day’s activities. What exactly was he after?

He put on his walking shoes and a warm jacket and set out from his small rented house (should he try to buy it? he wondered) to the waterfront, less than half a mile distant. It was along its serene shores, watching bobbing fishing boats and seagulls, that he often did his most creative thinking. There was a blustery wind but the temperature was unusually mild for November.

It was Mandalstram’s affair with Margarita that had triggered the breakup with Louella, and his second marriage had ended just as badly as the first. Even worse, perhaps, because there was, to use a phrase he found delicious in its ironies, collateral damage. Again, they had been young, and ill prepared not only for the poverty-dogged relationship but the parenthood that had accompanied it. Margarita was a painter with a promising future and the detour that motherhood caused in her career embittered her, not toward the child, thankfully, but toward Mandalstram, as if everything that followed from that first passionate coming together had been the fault of his sperm, her egg having been merely an innocent bystander.

Of course, it helped not a whit that Mandalstram was a terrible father, incompetent and disinterested. After the breakup, he made half-hearted attempts to keep in touch with the child—a delightful little girl named Sunshine, whose blond ringlets and cherubic cheeks seemed almost contrived—but they had eventually become estranged. The last time he’d seen her, when she was nearing puberty, most of the shine had already rubbed off the girl, and she was cocooned in an impenetrable swirl of hurt and sulk. Mandalstram hadn’t thought much about either his daughter or her mother in the years since—though Sunshine’s birthday would always bring him pangs of guilt and regret—but now he found himself inexplicably filled with an intense longing to see the girl—she would, in fact, be a woman of close to 30. According to one acquaintance he’d phoned, she lived in Southern California and was well-established as a publicist for Hollywood films, often traveling abroad to be on location—her name could be seen at the end of the occasional movie in the fast-moving welter of credits; although she had disavowed her father, she inexplicably continued to use his name, apparently.

Mandalstram bought a chicken salad sandwich on a French baguette at an open-air stand near the dock and, while leaning against a railing overlooking rocks and water, washed it down with an ice-cold locally produced root beer from a bottle. This lunch was so simple and brought such pleasure, but previously had been beyond his means other than as a very occasional treat. He had hopes now of enjoying such a midday meal once or even twice a week.

He fed crusts of bread to gulls and ducks as he contemplated his next steps. Apology, he now realized, was the driving force behind this project, which was still taking shape in his head. At first, he’d thought of it strictly as an exercise in clearing the decks, touching base with people who had been important to him at this, a significant moment in his life. It wasn’t their congratulations or good wishes he was after—he’d thought he merely wanted to assure himself that things were unfolding as positively in their orbits as they were in his, so unusual was his good fortune. His clumsy attempt to apologize to his first wife for old crimes, real and imagined, had surprised him as much as it must have her. Now it was becoming clear to him that what he was after was, if not redemption or even forgiveness exactly, something along those lines. “Poet of the heartbroken,” the jury had written, “a connoisseur of longing.” He had focused on the latter, the longing part of that curious equation; now, the former was resonating more. Was not giving voice to the heartbroken the special brief of the novelist?

At the same time, he realized, he still wasn’t exactly sure what those labels meant—so laudatory, on first reading, but were they really? Had the jury intended some form of sly irony?

*

When Mandalstram had begun to write, over thirty years earlier—first poetry, then moody, introspective stories, then complex, layered novels—his art was very much informed by the experience of his parents, though he knew so little of it. A large supporting cast of Jews, Communists, Germans and refugees from one disaster or another crept into his stories, usually as minor characters, though occasionally one would shoulder his way to the forefront. Many pieces involved children of Holocaust survivors; a story and several poems were actually set in concentration camps. One academic critic, writing about Mandalstram’s third novel, identified exodus—flight, persecution, the refugee experience—as a major theme in his work. Still, when an article in Border Crossings, a magazine primarily of the visual arts, mentioned his name in connection with a growing number of Canadian artists of various disciplines influenced by the Holocaust, he was surprised.

He began to be invited occasionally to do readings at temples or participate in Jewish book fairs, and to be mentioned, along with better known writers, like Richler and the Cohens, Leonard and Matt, as representing a new Canadian Jewish literary renaissance, a misapprehension he did nothing to correct, and from that point on—the Border Crossings piece—the Holocaust specifically and genocide in general became central preoccupations in his work. The recent novel that had won the award was the first in almost two decades in which those themes had been entirely absent, and it had been produced during a pause he had taken in a big novel, his most ambitious undertaking yet, overwhelming, really, that revolved around a large cast of Holocaust survivors, perpetrators and collaborators, and their children.

It was to this novel he now intended to return, with renewed vigour. But first he needed to play out the admittedly perverse string he’d begun that morning.

*

Here was the score, as he recorded it on the back of that sheet of hotel stationary on which this plot had first been hatched, only a few days earlier. Wife one, a strike out; wife two and daughter, both missing in action. That left wife three, but Mandalstram wasn’t yet ready to tackle that particular challenge, which might, he knew, prove to be the thorniest.

There had been a number of other women in his life, of course; he wasn’t sure which of them he might want to now pursue. Nor had he given up on the search for his daughter, and, should he find her, she might direct him to Margarita. He was thinking all this as he sat tossing pebbles into the placid water under his favourite tree, an expansive oak that leaned seaward from a spit of land jutting in the same direction. All the signs seemed to be directing him eastward, toward Europe, the familial homeland. With each pebble, he counted the concentric rings produced on the face of the water. There were other dusty corners of his life worth investigating, he thought. On the list he’d drawn up, after “wives,” “lovers” and “family,” he’d written “friends.”

He had been an indifferent and undistinguished student. Of his grade school and high school years in the Bronx, he had few pleasant recollections, and there certainly were no teachers who stood out in his memory. Unlike some of his friends who spoke warmly of the influence one particular teacher or another had had on their lives, Mandalstram had encountered no such mentor, not even in college, in the States—where he’d attended City College in Manhattan for two years before the furor over the war had overtaken his studies—or university in Canada, where he had finally obtained a degree, in comparative literature, from Concordia. A few professors had been friendly, certainly, but none to the extent that a friendship off campus had evolved. None had even been particularly encouraging, as far as he could recall.

As far as friends went, though, there was one old childhood chum, whom he’d become reacquainted with out of the blue a few years earlier, and quite a few from later years, including a handful of close friends from student politics days, on both sides of the border. As he walked back toward his house, he sorted through various names and faces, drawing up a tentative list of people to call. At the top was Hal Wolfowitz.

*

There was an email, several actually, he was looking for. They weren’t in his computer’s in-basket, or in the folder marked Friends, nor were they in Trash, where thousands of old email messages of all sorts gathered dust and, for all Mandalstram knew, plotted conspiracies. Finally, though, in the Sent directory, he found an email he’d written in reply to one from Wolfowitz that contained a record of previous exchanges.

The thread began with a note from someone—the name had rung no immediate bell—asking if he was the Franklin Mandalstram who had once lived on West 183rd Street near the Grand Concourse in the Bronx? If he was, then perhaps he would recall the author of the email, Hal Wolfowitz, who had been a classmate and friend all through grade school. He was now a professor of history at—of all places—the University of New Mexico, having traveled even further from the Bronx than Mandalstram had, at least in terms of miles.

Once having adjusted the context, he remembered Hal very well—in his memory, they were not just friends but best friends, the boy he’d spent countless hours with swapping comic books and records, talking baseball statistics and girls—and they’d exchanged several nostalgic emails since, mostly pondering how it was that they had drifted apart and lost touch—though none in the last year or two. A reading of the email trail seemed to suggest the fault was chiefly Mandalstram’s. Now, having secured a phone number on the internet, Mandalstram was listening to a phone ring in a university office somewhere in Albuquerque. The voice that answered, though, was female.

“Professor Wolfowitz, please,” Mandalstram said.

There was a pause. “May I ask who’s calling?”

“Franklin Mandalstram. I’m calling from Halifax, in Canada. For Hal Wolfowitz? We’re old friends.”

Another pause. “I’m sorry to have to tell you then that Professor Wolfowitz is dead.”

“God,” Mandalstram said.

“It just happened last week, a heart attack, at his desk. The funeral was Monday.”

Mandalstram poured himself a stiff shot of Bushmill’s Black Bush Irish whiskey, his drink of choice when he could afford it, and bolted it back, then poured another to sip from. This wasn’t going well, and he was beginning to wonder what exactly he was hoping to achieve. It was only mid-afternoon, though, and having come this far, he determined to persevere.

Mandalstram and Martin Semple had come to Canada together as draft resisters in the early ‘70s and had even lived together briefly in their first months in Montreal. Martin had gone back to the States after the amnesty of 1977, but they had kept sporadically in touch, though Mandalstram couldn’t remember the last time. Semple had finished university, gone on for a doctorate in French literature and now was a professor at NYU—presuming he too hadn’t prematurely died. The first number in his address book, a New York City number, was not in service; but a second number, with an unfamiliar area code, produced a ring that was eventually answered by someone with a very young voice, sex undeterminable. After the usual semi-comic interplay—“is Mr. Semple there?” “Mr. Who?” “Well, let me speak to your father…?” and so on—Martin came on the line.

“Franklin?” he said after he finally understood who was calling. “What the hell do you want, you son of a bitch?” A sentence like that, pronounced in a jocular tone, could be the start of a pleasant, jokey conversation, but Martin’s tone was not particularly jocular, making Mandalstram wary.

“I’m just calling to say hello, Marty.”

“For Christ’s sake, what is it?”

Mandalstram was confused. Unlike his first wife, whose enmity he fully understood, he had no recollection of any bad blood between him and Martin.

“Just that, Marty. No ulterior motives, honest. Not wanting to borrow money, asking no favours, nothing like that. Not even calling to spread gossip.” Mandalstram chuckled, then paused to allow Martin to respond, but there was no response, so he went on. “Actually, there was something I’ve been wondering about, something I wanted to talk to you about.”

“If it’s about the money you already owe me, forget it,” Semple said. “I wrote that bad debt off long ago.”

“Money? I didn’t realize I owed you money, Marty. That I owe you, yes, of course, but money? I don’t recall.”

“Listen, like I said, forget it. Water over the bridge.”

“It happens that I’ve recently come into some unexpected money. How much was it?”

“Didn’t you hear what I said? Forget about it. I have.”

“Well, then, I’d like to ask you about…well, you remember that year we lived together.”

“How could I forget?

“And you remember Ingrid? That waitress you went around with for a while?”

There was no response.

“This will seem crazy, but do you remember, once we had a very brief argument over her?”

Again, silence from the other end of the line.

“I don’t remember what I said exactly, but something about her that you took exception to. You probably don’t even remember this, it was so trivial. I don’t think we ever discussed it again.”

More silence.

“Marty, you still there?”

Silence, then, finally, a frigid “I’m here.”

“So, do you remember….”

“I remember you fucked my girlfriend, you asshole, I do remember that. I remember you didn’t say anything about that.”

“Martin, I….”

“I remember you fucked the woman who became my wife, shithead. And there was something you wanted to ask me? Forgiveness?”

“Well….”

“Listen, Franklin, don’t call here again.” With that, the line went dead.

Mandalstram was stunned. He only barely remembered having had sex with Ingrid, and had no idea she and Marty had gotten married. That must have happened after he went back to New York—she had followed? Mandalstram’s memory of that period was murky at best. He hadn’t even known they were serious, although that must have been why whatever he had said back then caused the argument. A brief trivial argument, at least that’s what he had thought at the time.

Mandalstram went to the window in his bedroom, which had a better view of the street than the living room’s. He stood for a long time watching foot and vehicle traffic. A Buick from the ‘80s pulled up across the street and expelled a man in an ill-fitting dark suit who consulted a piece of paper from his pocket, then re-entered the car, which sped away. A truck rumbled past, driven by a man with thick dark hair on his arm, which swung like a symphony conductor’s from his open window. Two boys on bicycles rode by, their laughter trailing after them in the balmy air. An attractive young woman in a polka dot dress walked down the street swinging her handbag, followed by an old woman, the woman who lived two houses down, in black. A dog, a nondescript mutt, zigzagged across the street, then back, sniffing the air.

A dark stream of sadness coursed through Mandalstram as he watched the tableau of life, limited as it was on this particular street in this particular city, unfold before his eyes. In his mind, he drew a line through the name of his third wife, having determined to let that particular sleeping dog lie. He still had a longing to connect with his daughter—and he would, he determined—she was out there somewhere, and he would find her. How many Mandalstrams could there be in Hollywood? And might not she actually be pleased to hear from her father, estranged though they were? But in other respects, he would leave the past alone. He had enough trouble coping with the heartbreak of the present, with his longing for a future.

—Dave Margoshes

.

Dave Margoshes is a Saskatchewan writer whose work has appeared widely in Canadian literary magazines and anthologies, including six times in the Best Canadian Stories volumes. He was a finalist for the Journey Prize, Canada’s premier short story award, in 2009. He’s published over a dozen books, including Bix’s Trumpet and Other Stories, which was named Saskatchewan Book of the Year in 2007, and A Book of Great Worth, a collection of linked short stories that was among Amazon.Ca’s Top Hundred Books of 2012. “The Connoisseur of Longing” is part of a new collection, God Telling a Joke and Other Stories, published in spring 2014. A new novel, Wiseman’s Wager, is due out in the fall. He lives on a farm outside Saskatoon.