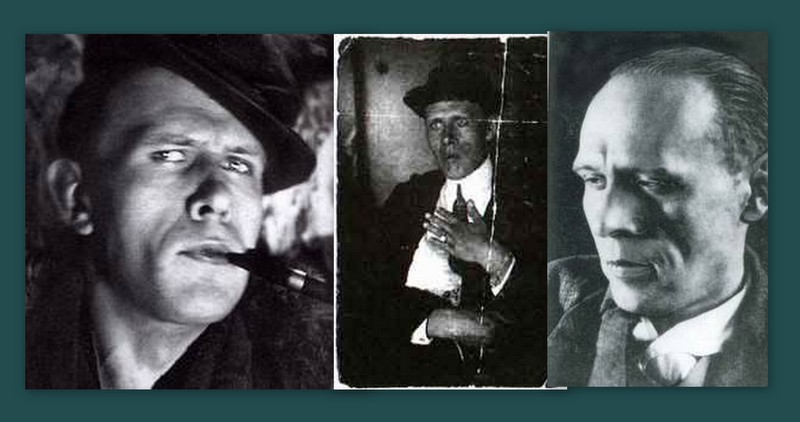

The minimalism of Absurdism is tautological, taking a perverse, morbidly dry pleasure in stories that, like much of life, go nowhere, a very literal practice of the idea that art, poetry “makes nothing happen” (of course not taken from Auden, but a product of a similar historical disenchantment). The artlessness of Daniil Kharms, in accord with his age (in the wake of Satie, and Duchamp and Ernst, Kokoschka and the German Expressionists, yet almost certainly unaware of them and without precedent other than say Gogol in Russian) is Anti-art. (The designation of the Russian Absurdists for themselves was Oberiu, short for Ob’edinenie real’novo iskusstva, the tongue-in-cheek “Association for REAL Art”.) Minimalism as insufficiency of the word qua communication was already in the air when Kharm’s came of age in the 1920s, during the end-stage of Russian Futurism (particularly notable are Vasilisk Gnedov, whose logical conclusion was his “Poem of the End” (a blank page), and the Constructivist poet Ilya Selvinsky; see my tribute to the centennial of Russian Futurism at www.em-review.com.)

Thumb-twiddling boredom, repetition, hoaxes, and other violations of expectations in evidence here are dissonant and discomfiting in themselves. Elsewhere, Kharms strikes a more distasteful, even offensive pose, an epatage that practically wallows in degradation and self-degradation. Explaining his “program” he wrote: “I am interested only in absolute nonsense, only in that which has no practical meaning. I am interested in life only in its absurd manifestation. I find abhorrent heroics, pathos, moralizing, all that is hygienic and tasteful … both as words and as feelings.” In his other work we may find a precedent, for example, for The Theater of Cruelty, but also in its minutia of daily life for the post-modernist, documentary yet ironic and paradoxical approach of the Moscow Conceptualist artists and poets of the 1970s who acknowledged Kharms as an essential influence.

One of them, Ilya Kabakov, wrote: “…Contact with nothing, emptiness makes up, we feel, the basic peculiarity of Russian conceptualism….” Kharms was similarly central for the non-conformist poets of the 1950s and 60s (Yevgeny Kropivnitsky, Vsevolod Nekrasov, Jan Satunovsky, Igor Kholin, Genrikh Sapgir, Alexei Khvostenko) and the Minimalist poets of the 1970s and 80s. Just to enumerate some of the aesthetic (or anti-aesthetic) values: plain speech, written as it is spoken, folksy simplicity, daily life or byt, but also the spiritual values of Absurdism: the ridiculous as a reaction and an alternative to revulsion and resignation before an Absurd age.

As I believe is true of all minimalist practice, the above not only doesn’t preclude a spiritual dimension, but makes it necessary. This particularly (also Kharms’s silly rhyming) is what is likely most incomprehensible to Anglophone readers of Kharms, and of the work of his colleague and friend, the proto-existentialist poet Alexander Vvedensky. How may their seeming nihilism (I would argue they were not) be made coherent with and even motivated by their conceptions of God? While the specifically Russian Orthodox context, particularly evident in Vvedensky’s writings (he was a genuinely religious person and writer,) but also in Kharms’s irreverence (he was the son of a religious mystical philosopher Ivan Yuvachev and seemingly an irrepressible person) is outside our scope, it may be fitting to end by noting that Kharms falls squarely within the Russian tradition of the yurodivy, the “holy fool,” even to the point of feigning insanity to avoid arrest. Daniil Kharms died in 1942, of starvation, in a psychiatric hospital during the Nazi siege of Leningrad.

—Alex Cigale

***

King of the universe,

dearest king of nature,

king who is nameless,

who hasn’t even a definite frame,

come over to my house

and together we will down vodka,

stuff ourselves with some meat,

and then discuss acquaintances.

Perhaps your visit will bring me

the Lord’s on high autograph,

or perhaps your photograph,

that I may your portrait depict.

(27 March 1934)

How strange it is, how inexpressibly strange, that behind this wall, behind this very wall, a man is sitting on the floor, stretching out his long legs in orange boots, an expression of malice on his face.

We need only drill a hole in the wall and look through it and immediately we would see this mean-spirited man sitting there.

But we shouldn’t think of him. What is he anyway? Is he not after all a portion of death in life, materialized out of our conception of emptiness? Whoever he may be, God bless him.

(undated)

.

Olga Forsh approached Alexei Tolstoy and did something.

Alexei Tolstoy did something too.

Then Konstantin Fedin and Valentin Stenich ran out into the yard and began searching for an appropriate stone. They didn’t find a stone, but they did find a shovel. With this shovel, Konstantin Fedin smacked Olga Forsh across her mug.

Then Alexei Tolstoy stripped off all his clothes and completely naked walked out onto the Fontanka and began to neigh like a horse. Everybody was saying: “There neighing is a major contemporary writer.” And no one even lay a hand on Alexei Tolstoy.

(1931)

At 2 o’clock past midday on Nevsky Prospect or, more precisely, on the Prospect of the 25th of October, nothing in particular happened. No no, that man standing by the Coliseum store stopped there purely by accident. Perhaps the shoelaces of his boots became untied, or maybe he stopped to light a cigarette. Or no, not that at all! He’s simply new in town and doesn’t know the way. But where then are his things? Well no, wait, now he is lifting up his head, as though wishing to look up at the third floor, or even the fourth floor, even the fifth. No, look again, he only sneezed and is now walking on. He is a bit hunched and holds his shoulders hiked up. His green greatcoat is blowing open in the wind. And now he just turned off onto Nadezhinskaya and disappeared behind a corner.

A man of Eastern extraction, a boot polisher, looked up in his wake and with his hand brushed smooth his luxurious black mustaches.

His coat is long, tight-fitting, and lilac in color, either checkered or, perhaps, stripped in pattern, or is it, the devil take it! all in polka dots.

(1931)

.

A little old man was scratching himself with both hands. Where he could not reach with both hands, the old man scratched with one hand only, but quickly-quickly and then, the whole time, while rapidly blinking his eyes.

(1933-34)

.

The window, shuttered with a curtain, was growing lighter and lighter, because the day had begun. The floors had began to creek, doors to sing, and chairs were being shuffled in the apartments. Ruzhetskii, climbing out his bed, fell on the floor and cracked open his face. He was in a hurry to get to work and therefore went out on the street having only covered his face with his hands. His hands were making it difficult for Ruzhetskii to see the way, and for this reason he twice collided with an advertising arcade and shoved some old man who was wearing a felt hat with fur ear flaps, which brought the geezer into such a state of rage, that a street sweeper who had just happened to be nearby and was attempting to catch a tomcat with a shovel, had to calm the old man down: “Aren’t you ashamed, grampa, at your age to be behaving like a teenage hooligan.”

(1935)

.

Kulakov squeezed himself into a deep armchair and immediately fell asleep. He fell asleep sitting up and several hours later woke up lying in a coffin. Kulakov realized right away that he was lying in a coffin and was seized with a paralyzing terror. With his clouded eyes he looked around, and everywhere, in every direction he could cast his gaze, he saw only flowers: flowers in baskets, bouquets of flowers, wrapped in ribbons, wreaths of flowers, and flowers scattered separately about.

“I am being buried,” Kulakov thought to himself, filling with horror, and suddenly felt a sense of pride, that he, such an insignificant person, was being buried with such pomp, and with such a quantity of flowers.

(1936)

.

I can’t imagine why but everyone thinks I’m a genius; but if you ask me, I’m no genius. Just yesterday I was telling them: Please hear me! What sort of a genius am I? And they tell me: What a genius! And I tell them: Well, what kind? But they don’t tell me what kind, they only repeat, genius this, genius that. But if you ask me, I’m no genius at all.

Wherever I go, they all immediately start whispering and pointing their fingers at me. “What is going on here?!” I say. But they don’t let me utter a word, and any minute now they will lift me up in the air and carry me off on their shoulders.

(1934-1936)

.

One man went to sleep with faith, and woke up faithless.

As luck would have it, in this man’s room stood very precise medical scales, and the man was in the habit of weighing himself daily, every morning and every night.

And so, before going to bed the previous evening, having weighed himself, the man determined that he weighed 4 stone and 21 pounds. And on the next morning, having woken up without faith, the man weighed himself again and determined that he now weighed only 4 stone and 13 pounds. “It may thus be determined,” the man concluded, “that my faith had weighed approximately eight pounds.”

(1936-1937)

.

Two men were talking animatedly. As they were speaking, one of them was stammering on the consonants, and the other one on the consonants and the vowels both.

When they stopped speaking, everything suddenly felt incredibly pleasant – as though the hissing of a gas stove had been shut off.

(1936-1937)

.

The Adventures of Mr. Caterpillar

Mishurin was a caterpillar. Because of this, or perhaps for another reason, he loved to wallow under the sofa or behind the dresser sucking in the dust. Because he was a somewhat slovenly person, sometimes for an entire day his mug would be covered in dust, as though with eider down.

Once upon a time he was invited as a guest to someone’s house, and Mishurin decided to give his countenance a light rinse. He filled a bowl with lukewarm water and added some vinegar to it and immersed his face in this water. As it turns out, this mixture contained too much vinegar, and for the rest of his long life Mishurin went blind. Into his deep old age, he walked around feeling his way about with his hands and for this reason, or perhaps another, he came to resemble a caterpillar even more.

(October 16, 1940)

The streets were becoming immersed in silence. At the intersections, people stood waiting for trolley buses. Some of them, having given up hope, set off on foot. And so at one of the intersections on the Petrograd side of town, only two people remained. One of them was particularly short in stature, with a round face and protruding ears. The other was slightly taller and, as was apparent, lame in his left foot. They were not acquainted with each other, but their common interest in the trolley bus forced them into conversing. The conversation was initiated by the lame one.

I don’t know what to do, he said, as though directing himself to no one. It’s probably not even worth waiting here.

The round-faced man turned toward the lame one and said:

I don’t think so, it might still come.

(1940)

I’m sitting here on a stool. And the stool stands on the floor. And the floor is part of the house. And the house stands on the ground. And the ground extends in all directions, to the right, and to the left, forwards and backwards. Is there an end to it anywhere?

It isn’t possible, that it doesn’t end somewhere! It must end at some point or other! And then what? Water? And the ground floats on water? That’s what people used to think. And they thought, that there, where the water ends, there is where it and the sky meet.

And indeed, if you stand on a steamship at sea, where all around nothing interrupts your vision, then that is what it seems, that somewhere very far away the sky descends and unites with the water.

And the sky appeared to people as a big solid cupola, made of something transparent, like glass. But that was before anyone knew about glass and they said the sky is made of crystal. And they called the sky firmament. And people thought the sky or firmament is the most solid thing there is, the most consistent. Everything may change, but the firmament will never change. And to this day, when we wish to say of something, that it will not change, we say: this must be confirmed.

And people saw how upon the sky the sun and the moon move, but the stars stand immobile. People began to pay closer attention to the stars and they noticed that the stars are distributed in the sky in the shape of figures. Here are seven stars placed in the form of a pot with a handle, here are three stars one following right upon another as though on a ruler. People learned to distinguish one star from another and they determined that the stars are also in motion, only all together, as though they are fixed to the sky and they move together with the sky itself. And people decided that the sky circles around the earth.

The people then divided the entire sky into distinct figures consisting of stars and each figure they called a constellation and each constellation they gave its own name.

And then people saw that not all stars move together with the sky but that there are some which wander among the other stars. And people called these stars planets.

(1931)

One man was chasing another, and the one running away was, in his turn, chasing a third one who, unaware he was being chased, was simply striding along on the pavement stones at a moderate pace.

(1940)

.

A Northern Fable

An old man, for no particular reason, went off into the forest. Then he returned and said: Old woman, hey, old woman!

And the old woman dropped dead. Ever since then, all rabbits are white in winter.

(undated)

.

Yes, I’m a poet forgotten by the sky.

Forgotten by the sky from days of old.

But once upon a time Phoebus and I

made a racket joined in a sweet choir.

Yes, there was a time when I and Phoebus

joined in a sweet choir and made a squall.

And there were days when I and Geb were

tight as drops of water and in clouds above

the thunder in its youth rang with laugher.

The thunder rolled flying after Geb and I

pouring from the heavens a golden light.

(1935-1937)

—Daniil Kharms translated by Alex Cigale

—————–

Alex Cigale has had his poems appear in Colorado, Green Mountains, North American, Tampa, and The Literary Reviews, and online in Drunken Boat and McSweeney’s. His translations from the Russian can be found in Ancora Imparo, Cimarron Review, Literary Imagination, Modern Poetry in Translation, Brooklyn Rail InTranslation, The Manhattan, St. Ann‘s, and Washington Square Reviews. Other Kharms translations by Alex Cigale have appeared in PEN America and Gargoyle, and online in Eleven Eleven (California College of the Arts), Offcourse (SUNY Albany) and Mayday Magazine. He is currently Assistant Professor at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.