Huck Out West picks up Huckleberry Finn’s adventures after he has indeed headed out to the territories and taken up a life as an itinerant in the American West. Essentially a drifter, Huck in this way fulfills the destiny inherent to his character as depicted in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, where he is content to float his way down the Great River to no particular destination beyond a loosely defined “freedom.” —Daniel Green

Huck Out West

Robert Coover

W. W. Norton, 2017

320 pages; $26.95

.

Robert Coover has been a presence on the American literary scene for over 50 years now. In many ways, the critical response to each new book he publishes continues to register the perception that he remains an adventurous writer who repeatedly offers challenges to convention, a perception in which Coover himself must take considerable satisfaction, as he is indeed one of the most consistently audacious and inventive of the first generation postmodernists his work partly represents. Coover’s novels and stories subvert both the abiding myths and shibboleths—sometimes outright lies—that animate American history, and the formal assumptions of literary storytelling, often by adopting the ostensible conventions of such storytelling but subjecting them to a kind of straight-faced parody. In his new novel, Huck Out West, Coover turns to such a strategy, in this case not simply mimicking the patterns or manner of an inherited narrative form, but creating a new and extended version of a specific, already existing work—a sequel, but one intended to provoke reflection on the earlier work’s cultural implications and its literary authority.

Coover has drawn on the elemental power of stories and storytelling going back to his first novel, The Origin of the Brunists, as well as the story collection Pricksongs and Descants, the latter including such stories as “The Door,” “The Gingerbread House,” and “The Magic Poker,” all of which invoke fairy tales and fables as both form and subject. Coover is one of the central figures in the rise of what came to be called “metafiction,” but where, say, John Barth wrote in books like Lost in the Funhouse a blatantly self-reflexive kind of story that proclaims its own fabrication, Coover dramatized the conditions of fiction-making allegorically, making storytelling itself the story. This is perhaps best illustrated in his novel The Universal Baseball Association, still arguably his best book and the most revealing of his fundamental preoccupations as a writer. The novel’s protagonist, J. Henry Waugh (JH Waugh), is the God-like creator of a fictional world that is ostensibly a make-believe baseball league but that de facto represents an alternative reality in which Henry can emotionally and intellectually invest apart from his unsatisfying and humdrum job as an accountant. Indeed, his investment in this reality becomes so all-encompassing that at the novel’s conclusion it would seem he has disappeared into it—albeit as the now withdrawn and omniscient deity who contemplates his creation without intervention.

Although a book like The Public Burning, probably Coover’s best-known and most controversial work, would not at first seem to feature the same sort of concerns informing The Universal Baseball Association—it is, after all, a novel about weighty issues related to politics and history, not about an obscure accountant dreaming his life away—but in fact The Public Burning is not really about politics and history—not directly, at least—but politics as representation, and the distorting effects the sensationalized and distorted forms of representation in America have on American history and culture. In both UBA and The Public Burning, we are shown how easily, even eagerly, human beings shape reality into fictions and subsequently insist on taking those fictions as reality, with predictably disastrous consequences. J. Henry Waugh exemplifies individually what American culture at large evidences more generally: the desire to refashion a recalcitrant reality into a simple, more manageable creation, in which we must force ourselves to believe or that repressed reality will disagreeably return.

A novel like The Public Burning eludes designation as a strictly “political” novel—and thus avoids seeming a dated artifact of a fading Cold War controversy—because it is not finally a representation of the Rosenberg case per se but a representation of the representations to which the Rosenberg case and its legacy have been submitted, an evocation of American depravity through the discursive forms—exemplified by the New York Times and Time magazine—and manufactured imagery—embodied in “Uncle Sam”—that shape and circulate the specific content of that depravity. If J. Henry Waugh retreats into his private invented reality to fill his own inner (and outer) void, in The Public Burning the emptiness is felt as a social loss, an absence of meaning, to be counteracted through the invented reality provided by Media myths and fantasies, myths that at their most destructive must be reinforced through the ritualized spectacle into which the Rosenbergs’ death is organized.

Since The Public Burning, Coover has published numerous, consistently lively works of fiction of various length (8 novels, including the mammoth sequel to The Origin of the Brunists, The Brunist Day of Wrath, 7 novellas, and 3 collections of short fiction). While these books never seem repetitive, they do return to a few obviously fruitful subjects—sports, fairy tales, movies—and can certainly be taken as continued variations on the self-reflexive strategies introduced in Pricksongs and Descants, Universal Baseball Association, and The Public Burning. At times this strategy is more muted, as in Gerald’s Party, which seems more purely an exercise in surrealism, while in other books the artifice is unconcealed, directly integrated into plot and setting, as in The Adventures of Lucky Pierre, one of Coover’s most underrated books that dramatizes the plight of a character caught in an ongoing fiction from which he cannot seem to escape, a fictional character aware of his own fictionality.

Coover has also produced a series of novel and novellas that foreground their own fictionality by presenting themselves as versions of a particular mode or genre of fiction. Dr. Chen’s Amazing Adventure is Coover’s take on science fiction. Ghost Town is a western, while Noir evokes the hard-boiled detective novel (as filtered through film noir). Such works could not exactly be categorized as pastiche, since they are not so much imitations as efforts to distill the genre to its most fundamental assumptions and most revealing practices. Nor could they really be called parodies, since the goal is not so much to spoof or ridicule the genre but to in a sense turn it inside out, make it disclose the specific ways a particular mode of storytelling lends its conventions toward motifs and typologies that in turn have worked to substitute themselves for the actualities those conventions were created to depict, preventing anything resembling a clear perception of historical and cultural actualities apart from these archetypal representations. In novels such as Pinocchio in Venice and now Huck Out West, Coover takes this strategy of metafictional mimicry a step farther by seizing upon a specific iconic text and reworking it, both as a kind of homage to the prior work but also to create a parallel text that echoes the original while it also sounds out the work’s tacit if partly concealed assumptions and elaborates on its latent if unspoken implications.

Huck Out West picks up Huckleberry Finn’s adventures after he has indeed headed out to the territories and taken up a life as an itinerant in the American West. Essentially a drifter, Huck in this way fulfills the destiny inherent to his character as depicted in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, where he is content to float his way down the Great River to no particular destination beyond a loosely defined “freedom.” If the objective in Huckleberry Finn for both Huck and his friend Jim (who seeks literal freedom from bondage) is obstructed through the auspices of Tom Sawyer, likewise in Huck Out West Tom causes his supposed best friend (“pards,” they call each other) mostly trouble for their friendship—in fact, in Huck Out West Tom threatens to hang Huck, an act only the most naïve reader would believe he does not intend to carry out. Tom, who literally rides back into Huck’s life (a little over halfway into the novel) on a white horse, again proves unreliable and self-serving, although in Huck Out West these character traits, which Coover has keenly abstracted from the portrayal of Tom in Twain’s novel, are much more deadly in their potential consequences (not only to Huck) than when expressed by Tom Sawyer the 12-year-old boy.

Before Tom makes his reappearance and ultimately sends Huck off on the same kind of open-ended adventure that concludes The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck brings us up to date on his life since his journey down the river, which includes riding along with Tom for the Pony Express. After Tom decides to head back east, nothing really captures Huck’s interest long enough for him stay in any one place, so when the novel’s present action begins he has settled into the life of a wanderer:

When [Tom] left, I carried on like before, hiring myself out to whosoever, because I didn’t know what else to do, but I was dreadful lonely. I wrangled horses, rode shotgun on coaches and wagon trains, murdered some buffaloes, worked with one or t’other army, fought some Indian wars, shooting and getting shot at, and didn’t think too much about any of it. I reckoned if I could earn some money, I could try to buy Jim’s freedom back, but I warn’t never nothing but stone broke.

Huck must decide whether to buy Jim’s freedom because shortly after heading west, Tom Sawyer consigned Jim back to slavery by selling him to a band of Cherokee Indians. Huck is regretful about this decision, but does not look for Jim after all. Eventually Huck does serendipitously encounter Jim, who has indeed attained his freedom and is now traveling with a wagon train of settlers that Huck is hired to guide. He has become a devout Christian and forgives Huck for apparently abandoning him, but this is the last we see of Jim in Huck Out West. It is on the one hand disappointing that Coover chooses not to engage with the specific racial issues raised by The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (as John Keene does in his updating of the novel in his book Counternarratives), but on the other hand, he does in effect transfer the theme of white American treatment of racial and ethnic minorities to the eliminationist campaign against Native Americans during the post-Civil War migration to the western “territories.” This campaign is represented most directly in the character of Custer (“General Hard Ass,” as Huck refers to him), but the historical forces portrayed in all of the novel’s actions converge around a broad account of a rapacious, mercenary America determined to extend its sovereignty over all the land it can exploit, with little regard for the devastation and suffering this expansion leaves in its wake.

Ultimately Huck Out West does mirror the Huck/Jim relationship of Huckleberry Finn in Huck’s pairing with a Lakota tribesman, Eeteh, who shares with Huck a general disinclination to bear down and work hard, preferring his own kind of independence, but who is nevertheless an adept storyteller in the Lakota tradition and regales Huck with tales about the trickster figure, Coyote. It is Eeteh who directs Huck to the Black Hills in order to elude General Hard Ass, whom Huck fears wants him imprisoned, or worse, for refusing an order, even though Huck was serving only as a civilian scout. Thus Huck finds himself living in a teepee in Deadwood Gulch, a pristine creek valley when Huck arrives but soon transformed into a muddy slough overrun with prospectors, their hangers-on, and all the hastily constructed buildings erected when gold is discovered. It is into this suddenly chaotic place that Tom Sawyer arrives as well, allegedly deputized by the federal government to bring order. What Tom really seeks to do in Deadwood Gulch is seize the main chance, to use it as the opportunity for the same sort of self-aggrandizement that is always Tom Sawyer’s ultimate motivation.

Huck can never quite accept this, even after Tom has threatened to hang him for defying Tom’s wishes. Rescued from Tom’s bluster by Eeteh (who brings along a few Lakota warriors for good measure), Huck replies to Tom’s predictable apology: “You’re my pard, Tom, always was. But it ain’t tolerable here for me no more. If you want to ride together again, come along with us now.” Tom demurs, and Huck rides off with Eeteh, but in this case lighting out for a territory more informed by Eeteh’s spontaneous, generally elastic storytelling than by the “stretchers” told by Tom, lies he tries to believe are true—or tries to convince others they should believe. Huck himself has earlier indicated he already understands the difference between Tom’s stories that hide reality and the kind of story that might be truer to Huck’s sense of reality: “Tom is always living in a story he read in a book so he knows what happens next, and sometimes it does. For me it ain’t like that. Something happens and then something else happens, and I’m in trouble again.”

Huck Out West is not as purely a picaresque narrative as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but Coover has certainly captured the nomadic state of Huck Finn’s soul. He has cannily discerned the essential nonconformity manifest in the character created by Mark Twain, and memorably transformed the adolescent’s lack of ambition into a more self-aware skepticism toward social expectations and cultural practices—while still preserving in Huck an ingenuous outlook that acknowledges what the world is like but remains free of malice or resentment. This quality is reflected in the colloquial eloquence of Huck’s narrative voice, which again Coover has adapted from the same quality found in Twain’s novel but has further developed into what may be the most impressive accomplishment in Huck Out West. Huck doesn’t merely sound “authentic”; his idiomatic expressiveness is sustained throughout the novel less to provide “color” than to establish Huck as a character able to render his circumstances persuasively through the integrity of his verbal presence.

If I did develop one reservation about Huck Out West while reading it, it was from the invocation of Custer as Huck’s bete noire and scourge of the West. This move threatens to make the novel too reminiscent of Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man, whose narrator also relates his peripatetic adventures in the Old West in a vernacular-laden voice. Perhaps this only indicates how much Berger himself may have been influenced by Huckleberry Finn, and the work of Mark Twain in general, but Berger’s Jack Crabb is primarily the means by which the novel effects its darkly comic burlesque of American myth-making. Huck Out West engages in its fair share of this sort of lampoonery as well, but ultimately it goes farther. Robert Coover provides a new version of the twice-told tale offering a radical representational strategy that still allows for dynamic storytelling, even as it interrogates its own process of representation.

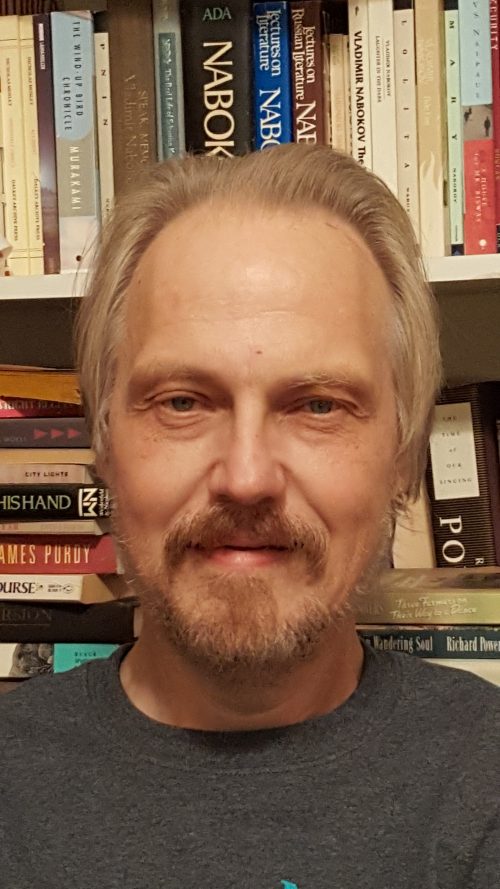

—Daniel Green

N5

Daniel Green is a writer and literary critic whose essays, reviews, and stories have appeared in a variety of publications. He is the author of Beyond the Blurb: On Critics and Criticism (2016).

.

.