Knausgaard peels back his more youthful self’s skin to reveal confusion, desire, and ineptitude without once asking for pity. —Jeff Bursey

My Struggle: Book Four

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translated by Donald Bartlett

Archipelago Books

Cloth, 485 pp; $27.00

ISBN: 9780914671176

.

1. Near the end of the latest installment of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s remarkable auto-fiction sequence collectively titled My Struggle, the nineteen-year-old narrator, angered by his family’s lukewarm reception to his short stories, makes a vow:

I’ll damn well show him [his brother Yngve]. I’ll damn well show the whole fucking world who I am and what I am made of. I’ll crush every single one of them. I’ll render every single one of them speechless. I will. I will. I damn well will. I’ll be so big no one is even close. No one. No. One. Never. Not a chance. I will be the greatest ever. The fucking idiots. I’ll damn well crush every one of them.

I had to be big. I had to be.

If not, I might as well end it all.

Born in 1968, Knausgaard won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature for his novel Ut av verden (Out of the World is a literal translation; it’s not available in English) in 1998, marking the first time the award had been won by a first-time author. A little over one year after the bulk of the events in My Struggle: Book Four Knausgaard had, if not crushed his family, established that he had talent. Six years later he proved the first book had not been a fluke when his second novel, En tid for alt (2004)—published by Archipelago as A Time for Everything (2009)—was nominated in 2005 for the Nordic Council Literature Prize, and other awards. He had become a notable writer on the Norwegian scene. The ego on display may be repellant or appear ridiculous, but for many writers the fierceness to exceed expectations can be ugly, and is often phrased in crude ways that most choose not to reveal. This passage, like so much else in the book, displays both the separation of a male teenager from his family as he sets out on his own for the first time, with only himself to rely on, and a confessional quality, without the shadow of catharsis often implied when we term poetry confessional. The statement that he’ll “crush every one of them” reminds us subtly that Min Kamp, the Norwegian title, is Mein Kampf in German, and is uttered with the earnest despair found in teenagers everywhere.

What put Knausgaard on the world stage, where he has been considered for the Nobel, the IMPAC, the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and other prestigious literary trophies, and seen his books published by Archipelago Books in hardback and in paperback under the Vintage brand, is the sequence of startlingly candid (or candid-seeming) works that, as has often been reported, took Norway by storm when they first appeared. Some are doubtful they are read with such intensity elsewhere. English novelist Tim Parks, resident grump for the New York Review of Books, in July 2014 wrote an article looking into how popular Knausgaard’s books are in English, and by implication questioning if they should be:

The curiosity with Knausgaard, then, is that the impression of huge and inevitable success was given not with the precedent of previous international success, but solely on the basis of the book’s remarkable sales in the author’s native Norway. Norway, however, is a country of only 5 million people—a population that is half the size of London’s—and of course the whole tone and content of My Struggle may very well be more immediate and appealing for those who share its language and culture; it is their world that is talked about.

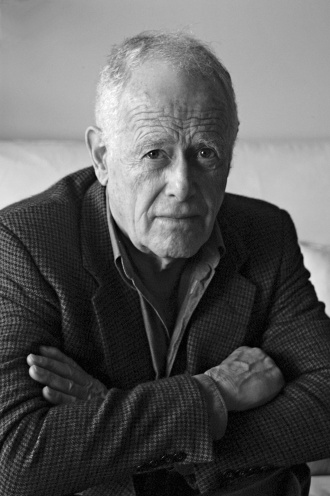

Parks may have been quite right on the sales figures at the time of his article, but he ventures beyond statistical analysis. It’s always good to be reminded, particularly by an Englishman who has lived in Italy for over thirty years (and translated Italo Calvino and Alberto Moravia), that London embodies the British Imperial standard for literature worldwide. The expression “their world” makes it seem that Norway is Mars and its population so unrepresentative and odd—never mind the rhetorical ruse “may very well”—compared to everyone else that their experiences scarcely resemble what people elsewhere go through. By these standards, English readers everywhere can dismiss Grass and Bolaño, Dostoevsky and Goethe. Yet on a trip in February I noticed, in various Canadian airport bookstores, the first three volumes of My Struggle in paperback, clearly meant for a mass audience, perhaps drawn in by the photographs of Knausgaard on the cover of each volume (already repackaged with explanatory titles for the mathematically fearful as, respectively, A Death in the Family, A Man in Love, and Boyhood Island; now there is Dancing in the Dark).

There are at least three notable constants about these books: they have enlivened the spring release season due to the writing power within them; they contain tension even in those passages, or pages, that some might consider editing out; and they set readers off in either the Zadie Smith way (“I just read 200 pages of it and I need the next volume like crack,” she has been reported as tweeting) or with skepticism about the literary merits of depicting seemingly dull affairs. There seems to be little middle ground. The latest volume will not bring those two ends together.

2.

Focusing on his time in a fishing village called Håfjord (population 250) in northern Norway, where the eighteen-year-old Karl Ove, as he is referred to, takes up a job as a first-time school teacher (who “hate[s] all authority”), My Struggle: Book Four explores several themes: the effects of isolation, especially as the hours of darkness increase; the proximity of females both contemporary and underage (thirteen-year-old students); the break-up of his parents’ marriage and the navigation required in two households; his sexual dysfunction; the importance of music and literature; and drinking. This is by no means an exhaustive list. It might be argued that any good novelist could take two or three of those and consider that sufficient material. Knausgaard is nothing if not ambitious, as his own words indicate, and as the preceding volumes have demonstrated he is able to juggle and combine complex topics as well as banal details.

In Book One the narrator freely moved from addressing one time period in his life to discussing others. (This is a feature of all the books.) Among other topics, that volume introduced his first marriage, his feelings towards his children by his second wife (which we see more of in Book Two), and his views on art. But its two main topics take in different stages of his life: the teenage years—bands he likes, friendships, and drinking, with the lowering shadow of his father present at all times—and, in the last two hundred or so pages, how an older Karl Ove and his brother Yngve deal with the death of their father, and the mental decline of their paternal grandmother, in the wretched house they shared. Few pages have stayed with me in the same way as those. A seemingly sad and normal thing—going through a dead man’s possessions and tidying a home—are packed with insights, incident, drama, believable mood swings, and the fear that their father may not be dead at all, with excellent pacing. In Book Two the father is placed to the side, and the emphasis is on how Karl Ove presses ahead with writing against the demands for more time with the family from his second wife, who he loves, and the requirements of their children. This time the narrator has friends with whom he can talk writing, and his world has expanded. As in the first volume, there are scenes of drunkenness and self-denigration. Book Three is about his childhood, and here we are shown, more visibly than before, the cruelty visited on Karl Ove and Yngve by their father, and how their mother rarely intervened.

In each of the previous books there is one major line of tension that runs throughout. In the first and third volumes this is provided by the presence of the father (even when he is absent), and in the second it is generated by what might be termed as the intransigence of Karl Ove to bow to society’s demands that he embrace the role of father and husband above that of an artist. In the newest volume the strain is provided by his actions when teaching (he often feels nervous) and when drunk; he can’t be trusted not to make a misstep or to do something cringe-worthy. Knausgaard peels back his more youthful self’s skin to reveal confusion, desire, and ineptitude without once asking for pity. Karl Ove regularly embarrasses himself by drinking too much and not being able to recall how he got home, and he ejaculates prematurely with every girl he is fortunate enough to have sex with (and for that reason avoids spending too much time with some of them). His attempts to hide the evidence of his emissions from them and from his mother, who does the laundry, can be seen as pathetic or laughable or, usually, somewhere in between. There are frequent scenes where he is sneaky, belligerent, or a thief, and he is prone to tears when caught or called to account for his behaviour. When two male villagers come by his home he is acutely aware of their masculinity, “it filled the whole flat and made me feel weak and girly.” He regards himself as “a kind of freak, a monster…” Only a portion of this can be attributed to normal teenage angst.

Karl Ove is a social misfit who nevertheless becomes quite popular in Håfjord with the young girls he teaches. Lessons begin well enough, but he doesn’t have the training to keep his composure. When three of his thirteen-year-old students, all girls, visit him at his home—a common practice in a small place where children and teenagers look for escape from boredom—he is discomforted. He has already had to hide erections in class. That he is a virgin, a state of affairs he is desperate to change, sharpens the edge of his appetite. Given the Scandinavian setting, one is inclined to think a porn movie will break out at any moment. There are many lines like this one: “[Liv] was walking beside Camilla as I arrived, and she sent me a stolen glance as she turned into the corridor. I eyed her slim firm backside, formed to perfection, and a kind of abyss opened inside me.” Balancing this, he is trusted by a young boy named Jo when they’re out walking the school grounds. “Didn’t he understand how this would look to his classmates, walking around hand in hand with the teacher?” The unpopular boy draws comfort from his teacher, something that Karl Ove notices, and he does not withdraw his hand despite reservations on Jo’s behalf. It requires work on the part of the sensitive teacher to create distance.

Despite his growing interest in one student, Karl Ove does not cross the line. His more important struggle is with what he wants to do with his life. On his first day as a teacher he emerges from a classroom “almost jubilant” at how things went only to realize, a few moments later, that “this was not what I wanted, for Christ’s sake, I was a teacher, was there anything sadder than that?” Against that he sets aside time to write those short stories his family will read, but that time comes between parties and binges, walks and short trips to other communities, and humiliating himself.

3.

Music and literature play significant roles in My Struggle. Book Four shows Karl Ove deepening his appreciation for both, partly as a way of keeping some semblance of familiarity around him in new surroundings, and partly in an effort to extend his knowledge of what is happening in both fields. At age sixteen he had started writing a new music review column for newspapers. “Thanks to music I became someone who was at the forefront, someone you had to admire, not as much as you had to admire those who made the music, admittedly, but as a listener I was in the vanguard.” He brings Roxy Music, Fripp and Eno, David Bowie, Talking Heads, the Smiths, and Simple Minds, as well as Scandinavian bands, to Håfjord, though in his temporary home there are few who regard his taste with the appropriate respect, “but there were circles where it was seen and appreciated. And that was where I was heading.” In literature, his preference is for regional writers and figures more familiar to English readers (Hubert Selby, Jr., Jack Kerouac, and Charles Bukowski), but he wants to be more aware of new thinking about fiction, such as the innovations of Jan Kjærstad in The Big Adventure. When Karl Ove encounters an article on Ulysses for the first time he slots that unread book alongside works by Hermann Broch, Robert Musil, Arnold Schönberg, Thomas Mann, and Knut Hamsun.

The latter plays more than one role here. The quiet, and natural-seeming, introduction of Hamsun occurs in a book that includes the opinion Karl Ove’s paternal grandfather has on refugees: “‘We’ve slogged our guts out and we’ve done well, and now they want to take over. Without lifting a finger. Why should we allow that?’” (171) Unlike his father, Karl Ove is open to helping the refugees. Hamsun’s own views were racist and right wing, in line with many Norwegians of his time and with the ideology of Nazi Germany. “Tolerance has never been Norway’s strong suit,” wrote Adam Shatz in the London Review of Books, discussing two books on the Norwegian mass killer Anders Breivik, who used a bomb and bullets to murder 77 people on 22 July 2011 (injuring many more) in an effort to staunch, in the words of Hugh Eakin, “‘Islamic colonization’ of the country abetted by the Labor Party’s ‘multiculturalist’ immigration policies.” Karl Ove and Yngve drive by both Hamsun’s “Nørholm property” (259) that the narrator remembers visiting with his ninth grade class, and “the old Hotel Norge, where Hamsun had done some of his writing…” He reads Pan (1894) when sixteen and living with his mother. The most substantial literary reference has Karl Ove preferring his countryman over Milan Kundera because “no one went as far into his characters’ worlds as he did, and that was what I preferred, at least in a comparison of these two, the physicality and the realism of Hunger, for example.”

Reviews of earlier volumes of My Struggle (let alone readers of Norwegian) already know that the sixth and final volume has extended essays on Paul Celan and Adolf Hitler. In Knausgaard’s own words, it “…really does end in Norway, with Anders Breivik killing sixty-nine children on Utøya Island. This happened while I was writing… And the novel ends there, in that place, in that collision of the abstract heaven we have above us and our own physical earth. Which is what Breivik’s killings were.” Much of the content of My Struggle seems to have been written in an associative style, but it is hard not to view the use of Hamsun and, by implication, his political views as foreshadowing a castigation of Norwegian attitudes about people who are considered too different from them.

In a recent Paris Review interview with James Wood (No. 211, Winter 2014), Knausgaard speaks directly on matters in Norway:

There is a new kind of moralism evolving, where the obligation is to the language—there are some words you can no longer say and some opinions you no longer can express. This is a kind of make-believe. It makes everybody comfortable, they feel good about themselves, because they mean well—while at the same time there is a whole generation of immigrants locked out from education, work, and privileges and there is anger growing in the part of the population that doesn’t have its voices heard, or whose opinions are considered evil and kept out.

While ideology has little part to play in Book Four, occasionally there are mentions of politics (but not ideology), and Karl Ove sees himself as a radical. He likes to read Hamsun, too. Another contradiction in a work filled with them.

4.

As he states in the quotation at the top of this review, the price of failure to achieve Karl Ove’s sizeable goals is high: “If not, I might as well end it all.” That can’t be taken lightly. His fellow countryman and contemporary, Stig Sæterbakken (1966-2012), wrote: “The need to become intoxicated bears a close affinity to the desire for death. Which itself is in the same family with an incurable Unfähigkeit [inability], […] vis-à-vis the realities of adult life.” At different points Karl Ove describes his blackouts: “…I was in the void of my soul…”; “we slowly but surely got drunker until in the end everything disintegrated and I drifted into a kind of ghost world.” His reliance on alcohol, from age sixteen to nineteen, to make him at ease in the world, could push him down the road to death his father is already traveling. It’s a coping strategy or inheritance he never explicitly notes, preferring to justify (rationalize doesn’t seem quite the right word) drinking to excess: “I drank though, and the more I drank the more it eased my discomfort.” He recalls one “alcoholic high” as similar to “a cool green river flowing through my veins. Everything was in my power.” The kinship to his father is ignored: “It didn’t matter to me that Dad had clearly split into two different personalities, one when he was drinking and one when he wasn’t… it wasn’t something I gave much thought.” (249) Further: “I wanted to steal, drink, smoke hash, and experiment with other drugs… But then there was all the rest of me inside that wanted to be a serious student, a decent son, a good person. If only I could blow that to smithereens!” It isn’t a surprise that the young Karl Ove does not examine the resemblance of his divided nature to that of his father’s; the farthest he can go is to acknowledge that, like his father, he is seen as “unreliable.”

Amid the teaching and the socializing there is fiction to write. Brief summaries are provided of a few of Karl Ove’s stories, and his thinking about how to write matures as time goes on. He vehemently rejects capturing what a friend and fellow teacher calls “‘God’s wondrous creation! All the colors! All the plants!’” Karl Ove replies that nature is “‘a cliché,’” yet that doesn’t mean he refuses to appreciate his surroundings. As the bus he’s on approaches Håfjord, emerging from a tunnel, he has an emotional reaction:

… Between two long rugged chains of mountains, perilously steep and treeless, lay a narrow fjord, and beyond it, like a vast blue plain, the sea.

Ohhh.

The road the bus followed hugged the mountainside. To see as much of the landscape as I could I stood up and crossed to the other row of seats…. The mountains continued for perhaps a kilometer. Closest to us, the slopes were clad in green, but further away they were completely bare and gray and fell away with a sheer drop into the sea.

The bus passed through another grotto-like tunnel. At the other end, on a relatively gentle mountain slope, in a shallow bowl, lay the village, where I would be spending the next year.

Oh my God.

This was spectacular!

There are many such passages that evoke the beauty, and the smallness, of this village, and of the natural beauty that rings it. Perhaps thinking about nature is not as clichéd as writing about it.

5.

During the course of his interview with Knausgaard, James Wood remarked: “It’s obvious enough that in your work the insane attention to objects is an attempt to rescue them from loss, from the loss of meaning. It’s a tragedy of getting older.” (75) There could be more to it than that. Drinking to the point of oblivion, hypersensitivity to the moods of colleagues, friends, strangers and his pupils, hypervigilance when it comes to determining, on an instinctive level, who may be a threat—“Everything that came from the outside was dangerous”—and the compulsion to remember and recount everything, as if doing so would flush out that one memory or insight that would provide an answer to crucial questions, might indicate something else. Towards the end of Book Four, when recalling his time in Håfjord years after he left, Karl Ove wonders: “Did terrible things happen there? Did I do something I shouldn’t have done? Something awful? I mean beyond staggering around drunk and out of control at night?” It’s impossible to say, but taking into account all that he has said in four volumes, and his general nervousness, Karl Ove’s upbringing appears to have been traumatic.

In this book his father’s dictatorial ways diminish in intensity due to alcohol consumption, but the eighteen-year-old Karl Ove is right to remain wary in his company “…because when I observed him, and his eye caught mine, I could sense he was still there, the hardness, the coldness I had grown up with and still feared.” There are many unpleasant scenes, witnessed by the two brothers, involving their father and his new girlfriend, Unni, who becomes his wife. A family discussion between the two brothers and their mother occurs, and in it the mother admits she had blindly followed her husband: “‘…I always saw it from his side, what happened.’” Despite what happened in the past Karl Ove commits to being a good son. That could be regarded as the father having control without even needing to reinforce it, keeping him in line no matter what he did, or it could be an earnest desire to be a better man than his role model. In Knausgaard’s tactile, tumultuous, at times feverish, world both things could be true at the same time. Lines from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” come to mind: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself./ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

In My Struggle: Book Four Karl Ove Knausgaard has given us yet another packed work about a fragile, fragmented young man who has his first warranted moments of self-belief, but who slips back from confidence into a miserable dungeon of his own making. There are two volumes left, and though we leave Karl Ove in a changed state, with an acceptance at a writing school in Bergen, thanks to the previous volumes we know an easier life does not lie ahead despite material successes. That may be the best news for those enthralled by this universally appealing and astonishing set of works.

—Jeff Bursey

NC

Jeff Bursey is a Canadian literary critic, and author of the forthcoming picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press), and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His academic criticism has appeared most recently in Henry Miller: New Perspectives (Bloomsbury, 2015), a collection of essays on Miller and his works by various writers. Bursey is a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review and an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon. His reviews have appeared in, among others, American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Quarterly Conversation, Music & Literature, Rain Taxi, The Winnipeg Review and Review of Contemporary Fiction. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

Barthes, in his famous essay “

Barthes, in his famous essay “