“By the end of my time spent with Langley’s work that afternoon in the library, I was smitten. Here was a poet whose poems combined so many of the qualities I search for: precise attention to details of the physical world, control of rhythm, love of language, large-heartedness, confidant risk-taking, and an ability to balance ideas with images and sounds. Contemplative, yes, but not confessional. Both serious and seriously playful. Neither undemanding nor obtuse. Big plus: a modern, original, identifiable voice.” —Julie Larios

.

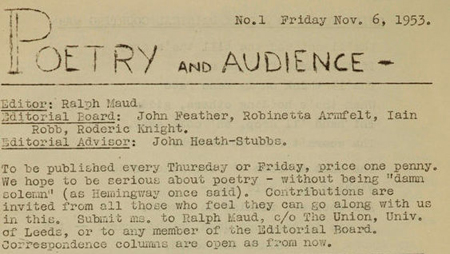

LIKE SEVERAL OF THE POETS I’ve written about for Undersung, Roger Francis Langley (known as R. F. Langley) was seriously unprolific. Seventeen poems were gathered together for one book, twenty-one poems for another. Apparently eight other poems appeared uncollected in The London Review of Books and PN Review. But unlike most other poets I’ve written about, Langley has not been a secret favorite of mine for years. In fact, I just heard about his work this January, when a friend mentioned a memoir titled H is for Hawk by the British writer Helen Macdonald. Macdonald, whose book recently won both the Costa Book Award for Biography and the Samuel Johnson Award for Non-Fiction, mentioned in an interview for The Guardian that, among a few other influential books which “opened her eyes to nature,” she had enjoyed a collection of diary entries by a poet I’d never heard of: R. F. Langley. Her description of that book, titled simply Journal, hooked me:

“These journals, Langley wrote, are concerned with ‘what Ruskin advocated as the prime necessity, that of seeing’, and pay ‘intense attention to the particular’. They speak of wasps, of thrips, grass moths, stained glass, nightjars, pub lunches and church monuments, everything deeply informed by etymology, history, psychology and aesthetic theory. The prose is compressed and fierce, and its narrative movement is concerned with mapping the processes of thought, the working out of things. It is founded on careful, close observation of things that typically pass unnoticed through our world.”

Being a fan of all things which pass unnoticed (or rarely noticed) I figured Langley’s journal might be worth looking through. Macdonald’s list of subjects (from thrips –thrips? – to pub lunches) intrigued me, and I was betting that Langley’s attention might be both focused and digressive, a combination that often produces fine essays. First, though, I had to see what kind of poetry he wrote.

I don’t own any of Langley’s books, and I couldn’t find individual poems anthologized in anything on my shelves. His work is not in my public library, and a search of databases produces not much more than basic biographical material (born in Warwickshire, England, 1938, educated at Cambridge, studied with poet Donald Davie, taught high school, retired to Suffolk, died 2011) and obituaries in major newspapers. Reviews and articles are few and far between, most of them simply remembrances. The obituaries warn that Langley did not produce a large body of work, having only begun to publish seriously in his sixties when he retired from forty years of teaching literature and art history to high school students.

There are only a few links to his poems online. Over at Amazon, his earlier out-of-print books/chapbooks are listed as “Unavailable at this time.” Later books listed there “may require extra time for shipping” which is code for any book that takes weeks to arrive from the U.K. and is obscure, published probably by a small European press. Luckily, I found two of Langley’s books (Collected Poems – 2002 – and The Face of It – 2007 – both still in print, published by Carcanet) at the university library near me and spent a slow afternoon reading them. The 2002 edition of Collected Poems (nominated for a Whitbread Book Award) contains only seventeen poems. It would be better titled Selected Poems; fortunately, a new edition is forthcoming from Carcanet in September of this year, and it is the definitive collection. It contains everything from the 2002 edition plus previously uncollected poems and supplementary material — I believe the total number of poems is 48.)

By the end of my reading that afternoon in the library, I was smitten. Here was a poet whose poems combined so many of the qualities I search for: precise attention to details of the physical world, control of rhythm, love of language, large-heartedness, confidant risk-taking, and an ability to balance ideas with images and sounds. Contemplative, yes, but not confessional. Both serious and seriously playful. Neither undemanding nor obtuse. Big plus: a modern, original, identifiable voice. Langley’s poem “To a Nightingale” was awarded the 2011 Forward Prize for Best Single Poem:

To a Nightingale

Nothing along the road. But

petals, maybe. Pink behind

and white inside. Nothing but

the coping of a bridge. Mutes

on the bricks, hard as putty,

then, in the sun, as metal.

Burls of Grimmia, hairy,

hoary, with their seed-capsules

uncurling. Red mites bowling

about on the baked lichen

and what look like casual

landings, striped flies, Helina,

Phaonia, could they be?

This month the lemon, I’ll say

primrose-coloured, moths, which flinch

along the hedge then turn in

to hide, are Yellow Shells not

Shaded Broad-bars. Lines waver.

Camptogramma. Heat off the

road and the nick-nack of names.

Scotopteryx. Darkwing. The

flutter. Doubles and blurs the

margin. Fuscous and white. Stop

at nothing. To stop here at

nothing, as a chaffinch sings

interminably, all day.

A chiff-chaff. Purring of two

turtle doves. Voices, and some

vibrate with tenderness. I

say none of this for love. It

is anyone’s giff-gaff. It

is anyone’s quelque chose.

No business of mine. Mites which

ramble. Caterpillars which

curl up as question marks. Then

one note, five times, louder each

time, followed, after a fraught

pause, by a soft cuckle of

wet pebbles, which I could call

a glottal rattle. I am

empty, stopped at nothing, as

I wait for this song to shoot.

The road is rising as it

passes the apple tree and

makes its approach to the bridge.

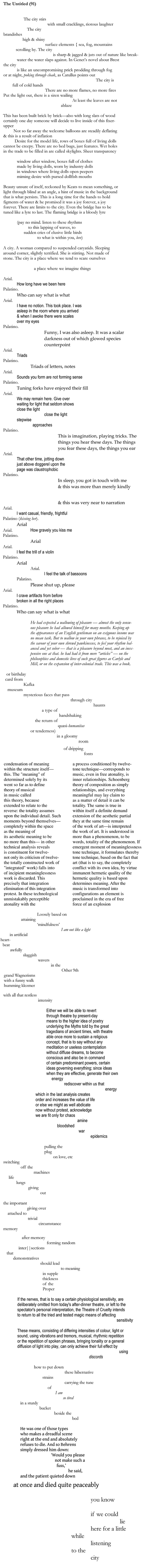

In this poem, Langley opens directly onto the physical world, minimizing the human presence, unlike “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats, where the speaker (all agony, in the Romantic mode) dominates the first forty lines of the poem. Nature is somewhere out there in Keats’s poem; his speaker says, “I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,” though he’s willing to take a few guesses. Langley’s poem, on the other hand, goes down to the ground immediately and sees clearly the non-human world: petals, burls, mites, lichen, flies, lemons, moths. The speaker of Langley’s poem is present only in his desire to name correctly what he sees and hears (a flower, “Helina / Phaonia, could they be?’ and a color “I’ll say / primrose-coloured” and a sound “which I could call a glottal rattle.”) Human involvement in the scene comes quietly:

Voices, and some

vibrate with tenderness. I

say none of this for love. It

is anyone’s giff-gaff. It

is anyone’s quelque chose.

No business of mine.

He does not romanticize nature, as Keats does when he compares the bird’s “full-throated ease” to a man’s being half in love with Death. Instead, Langley celebrates what is mysterious and even nervous about the natural world (“Caterpillars which / curl up as question marks” and the “fraught pause” of the nightingale, the bird finally making its appearance at the very end of the poem. The man in the scene stands still , but nature is in motion; for Langley, the speaker’s role is that of a careful observer of an active, natural world. William Wordsworth’s “Ode to a Nightingale” also begins with a man on a bridge and involves a nightingale’s song in the distance (no coincidence there – Langley is surely building on the English tradition of ornithological poems) but the center of that poem is also, as with Keats’s poem, clearly Man, not nature. Langley’s hidden subject might turn out to be the same upon careful observation, but his poetic trick is indirection. Langley, like many good poets, uses the tools of a good magician.

Look, too, at the subtler technical details of Langley’s poem, beyond the large idea it offers. It starts by saying “Nothing on the road.” Then, structurally, the poet unfolds his long list of everything that is actually there. He slows down after the opening four words and takes another look. And the poem come back structurally to that “nothing” by the end; the design of the poem is curvilinear, almost like the little caterpillar’s question mark.

I am

empty, stopped at nothing, as

I wait for this song to shoot.

The road is rising as it

passes the apple tree and

makes its approach to the bridge.

Like many of Marianne Moore’s poems (and like the quantitative verse of ancient Greece) this poem is built on counted syllables, with seven syllables per line, but without the lines feeling unnaturally stunted. Langley’s inspiration for this attention to the syllable was Charles Olson’s essay on “Projective Verse,” in which Olson says, “It comes to this: the use of a man, by himself and thus by others, lies in how he conceives his relation to nature, that force to which he owes his somewhat small existence. If he sprawl, he shall find little to sing but himself, and shall sing, nature has such paradoxical ways, by way of artificial forms outside himself. But if he stays inside himself, if he is contained within his nature as he is participant in the larger force, he will be able to listen, and his hearing through himself will give him secrets [that] objects share.” Olson goes on to say that the syllable is “king and pin of versification” and describes what syllables do as a dance. “It is by their syllables that words juxtapose in beauty, by these particles of sound as clearly as by the sense of the words which they compose.”

Counted syllables are not in and of themselves what a poet wants a reader to be aware of – the counting is simply part of the puzzle-making challenge the poet sets himself in order to see what kind of words will fill the particular vessel of the poem. Peter Turchi discusses a poet’s delight in this kind of challenge in his book A Muse and a Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery and Magic, reviewed in the January issue of Numero Cinq. Turchi also talks about nursery rhymes in that book; several of Langley’s poems involve nursery-rhyme rhythms:

You grig. You hob. You Tom, and what not,

with your moans! Your bones are rubber. Get back

out and do it all again. For all the

world an ape! For all the world Tom poke, Tom

tickle and Tom joke!

(excerpt from “Man Jack”)

Meter established by syllable count is not the only technical tool used in the poem; there is also a generous amount of internal rhyme:

To stop here at

nothing, as a chaffinch sings

interminably, all day.

A chiff-chaff. Purring of two

turtle doves. Voices, and some

vibrate with tenderness. I

say none of this for love. It

is anyone’s giff-gaff.

A light touch with alliteration also plays its part in the appeal of the poem: petals/pink, hairy/hoary, bridge/burls/bowling/baked, shells/shaded, nick-nack of names…alliteration runs through the poem, as does near-rhyme (“the soft cuckle/ of wet pebbles….”) With such a tight syllabic count, the choice of words that manage to chime off each other like that is especially difficult.

Then there’s the specificity of the Latin names, countered with the goofy sound of giff-gaff and chiff-chaff (which is actually a type of bird.) Langley had a naturalist’s command of information, a linguist’s command of etymology, plus good comedic timing and a modern voice in the style of Wallace Stevens. Some of his phrases in this poem seem non-sensical on first reading, until you look up the less-familiar meaning of a familiar word – the “coping of a bridge,” for example, refers to the architectural detail of its capped wall; “mutes on the bridge, hard as putty” are bird droppings.

Retired in 1999 at the age of 61 and able — finally — to turn his full attention to writing, Langley might have anticipated two decades to do so. But “To a Nightingale,” which appeared in the London Review of Books in November of 2010, was his last published poem; he died in January of 2011. As Jeremy Noel-Tod wrote in his remembrance of Langley for the Cambridge Literary Review, Langley managed to personify Keats’s notion of “negative capability,” that is, the state of “being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” In one poem about a medieval church in the moonlight, Langley says, “There are no / maps of moonlight. We find / peace in the room and don’t /ask what won’t be answered.” In “To a Nightingale,” there are no blunt answers, no overt message, nor is there any clear metaphor-making to draw lines between speaker and scene, yet we feel the mystery and melancholy in both, and we understand Langley’s play on the double-entendre of the word “coping” as it relates to both man and bridge, and the slight rise (of hope?) for both road and man as the poem ends. Daniel Eltringham summarized Langley’s skill in his article “‘The idea of the bird’: Bird Books, the Problem of Taxonomy, and Some Poems by R.F. Langley,” when he said, “Roger Langley’s writing lies between two worlds: the certainty desired by the amateur naturalist and its implications for artistic and taxonomic records, poised against the uncertain, plural, deferred, evasive character of an experimental artist. But poised without explicit tension: he is not a tense writer, more curious and exploratory, content to allow contradictions to remain contrary.”

Here is one more poem, offered up without commentary, other than to mention the character of Jack, who makes his appearance (like John Berryman’s Henry) in many later poems. There is also a noticeable use of end rhyme in this poem in addition to the internal rhyme, and the use of counted syllables (ten to the line.) You’ll see the same sensibility at play, the same fine control of sound, the barrage of images, the refusal to straighten it all out and over-explain. Some of the work, Langley seemed to believe, belongs to the poem’s readers.

Jack’s Pigeon

The coffee bowl called Part of Poland bursts

on the kitchen tiles like twenty thousand

souls. It means that much. By the betting shop,

Ophelia, the pigeon squab, thuds to

the gutter in convulsions, gaping for

forty thousand brothers. So much is such.

Jack leans on the wall. He says it’s true or

not; decides that right on nine is time for

the blue bee to come to the senna bush,

what hope was ever for a bowl so round,

so complete, in an afternoon’s best light,

and even where the pigeon went, after

she finished whispering goodnight. Meanwhile,

a screw or two of bloody paper towel

and one dead fledgling fallen from its nest

lie on Sweet Lady Street, and sharp white shards

of Arcopal, swept up with fluff and bits

of breadcrust, do for charitable prayers.

The bee came early. Must have done. It jumped

the gun. Jill and the children hadn’t come.

How hard things are. Jack sips his vinegar

and sniffs the sour dregs in each bottle in

the skip. Some, as he dumps them, jump back with

a shout of ‘Crack!’ He tests wrapping paper

and finds crocodiles. The bird stretched up its

head and nodded, opening its beak. It

tried to speak. I hope it’s dead. Bystanders

glanced, then neatly changed the name of every

street. Once this was Heaven’s Hill, but now the

clever devils nudge each other on the

pavement by the betting shop. Jill hurried

the children off their feet. Jack stood and shook.

He thought it clenched and maybe moved itself

an inch. No more. Not much. He couldn’t bring

himself to touch. And then he too had gone.

He’s just another one who saw, the man

who stopped outside the door, then shrugged, and checked

his scratchcard, and moved on. Nothing about

the yellow senna flowers when we get home.

No Jack. No bee. We leave it well alone.

Jack built himself a house to hide in and

take stock. This is his property in France.

First, in the middle of the table at

midday, the bowl. Firm, he would say, as rock.

The perfect circle on the solid block.

Second, somewhere, there is an empty sack.

Third, a particular angry dormouse,

in the comer of a broken shutter,

waiting a chance to run, before the owl

can get her. The kick of the hind legs of

his cat, left on the top step of a prance.

The bark of other peoples’ dogs, far off,

appropriately. Or a stranger’s cough.

His cows’ white eyelashes. Flies settled at

the roots of tails. What is it never fails?

Jack finds them, the young couple dressed in black,

and, sitting at the front, they both look up.

Her thin brown wrist twists her half open hand

to indicate the whole show overhead.

Rotating fingernails are painted red.

Who is the quiet guard with his elbow

braced against the pillar, thinking his thoughts

close to the stone? He is hard to make out,

and easy for shadows to take away.

Half gone in la nef lumineuse et rose.

A scarlet cardinal, Jack rather hoped.

A tired cyclist in a vermillion

anorak. Could anyone ever know?

Sit down awhile. Jill reads the posy in

her ring and then she smiles. The farmer owns

old cockerels which peck dirt. But he is

standing where he feels the swallows’ wings flirt

past him as they cut through the shed to reach

the sunlit yard, bringing a distant blue

into the comfortable gold. How much

can all this hold? To lie and eat. To kill

and worry. To toss and milk and kiss and

marry. To wake. To keep. To sow. Jack meets

me and we go to see what we must do.

The bird has turned round once, and now it’s still.

There’s no more to be done. No more be done.

And what there was, was what we didn’t do.

It needed two of us to move as one,

to shake hands with a hand that’s shaking, if

tint were to be tant, and breaking making.

Now, on the terrace, huddled in my chair,

we start to mend a bird that isn’t there,

fanning out feathers that had never grown

with clever fingers that are not our own:

stroking the lilac into the dove grey,

hearing the croodle that she couldn’t say.

Night wind gives a cool hoot in the neck of

Jack’s beer bottle, open on the table.

Triggered by this, the dormouse shoots along

the sill, illuminated well enough

for us to see her safely drop down through

the wriggling of the walnut tree to find

some parings of the fruit we ate today,

set out on the white concrete, under the

full presentation of the Milky Way.

Though Langley’s work is new to me, I want to put his name in front of readers here at Numero Cinq and to recommend that we all make the effort to find his work and read it. I’ve purchased his Journal and now wait for it to wing its way across the Atlantic and into my mailbox. If your library responds to World Cat requests, you might find copies of his books through that resource. Meanwhile, listen to the wonderful audio recordings he made for The Poetry Archive – he has a perfect reading voice, not melodramatic but full of feeling, which is no small accomplishment. There are two recordings available: first, the odd and interesting “Cook Ting” and then his compelling “Blues for Titania, ” which you can read along with as he reads it – it’s a complicated and masterly poem, four stanzas long, nineteen lines each stanza, eleven syllables per line, and swoon-worthy.

—Julie Larios

Julie Larios’s Undersung essays for Numéro Cinq have highlighted the work of George Starbuck, Robert Francis, Josephine Jacobsen, Adrien Stoutenburg, Marie Ponsot, Eugenio Montale, Alistair Reid and The Poet-Novelist; her own poems have been featured in our pages as well. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets prize and a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been chosen twice for The Best American Poetry series.

.

.