.

Cupertino is about process.

The process is about—

The process is—

.

The town, when I moved there, was a quiet, somewhat pleasant place at the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, with rather basic homes and cherry orchards here and there, half bedroom community, half unresolved. Most I ran into, like me, were starting out in life, on their way up and out. I largely knew Cupertino by the streets that led to the highways of my commute, 35 miles north to Hayward State on 280 and 30 miles south on 17 to UC Santa Cruz. I was a part-time college English instructor.

That was twenty-four years ago.

Marriage, a job in town at the community college, later a son—it was time to come to terms with what it was like where I lived. But also writing. Memories of other places had decayed, and those places had changed, perhaps beyond recognition. Writing, like life, is a matter of taking what you have before you and seeing what you can figure out. So I tried to discover the world I had bypassed.

I couldn’t find it.

.

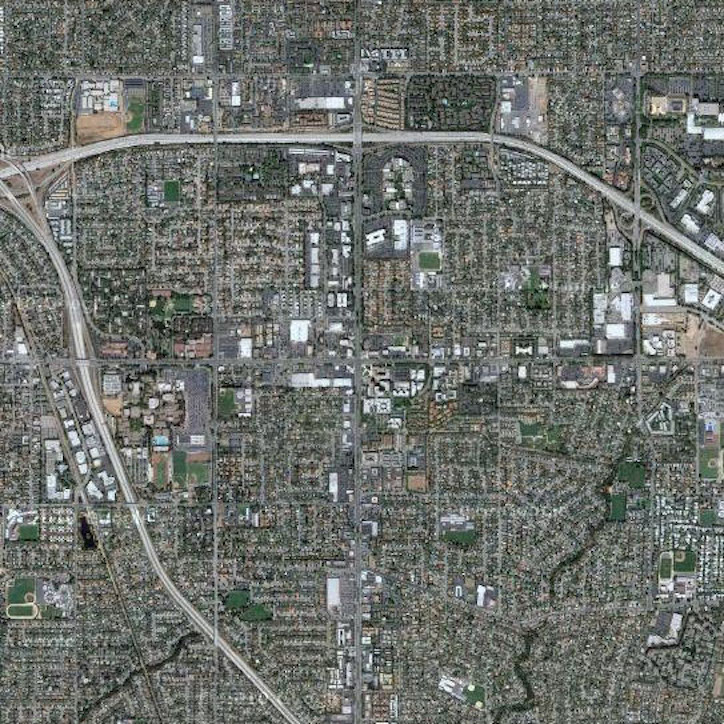

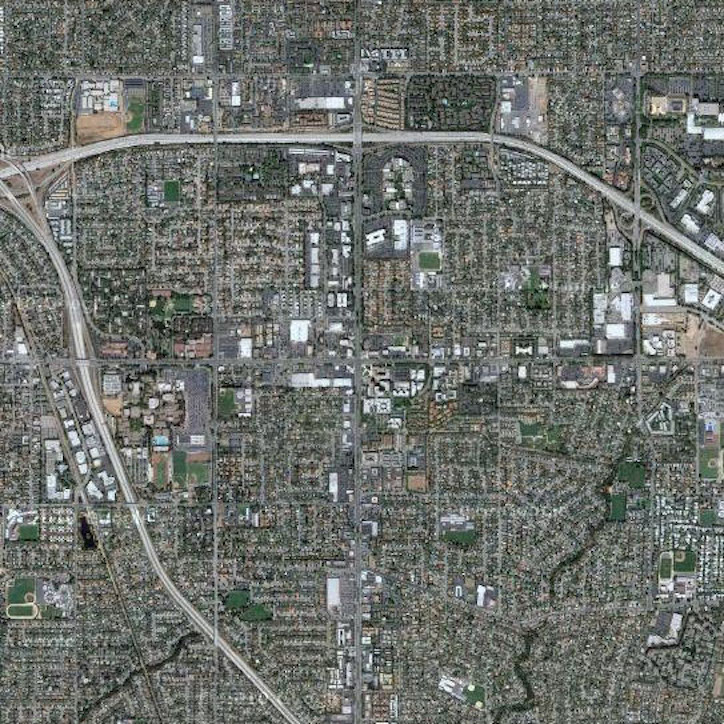

Cupertino now, above. Of course it looks like a blowup of an integrated circuit. Cupertino is in the heart of Silicon Valley, which is more a concept than a precise physical area, extending roughly from Stanford University down to San Jose. During the boom years the tech firms screamed for more green cards, and programmers and would-be entrepreneurs and still others poured in. Ranch houses started going for a million or were leveled and replaced with huge, stucco palaces on small lots. It amazed me anyone had that kind of money. The orchards are gone, and there is housing all the way up into the hills.

Apple has its corporate headquarters here, and other firms have main offices, large complexes they call campuses, worlds unto themselves. Employees refer to themselves collectively as families, as communities, who work together long, long hours to make deadlines and beat the competition as they rush to bring out a new program, the next release, the next bump in processor speed. It is easy to get caught up in their tempo. You become aware of the time it takes your screen to refresh, for numbers to crunch. Fractions of seconds begin to matter, you think about your pulse.

But those worlds are closed off from me. You need a badge.

Also scattered throughout the town, an orchard of small buildings with Apple logos out front, some of them places for special projects, so I’ve heard, where small teams work together, away from the fold. Along with these, other small, faceless buildings of other tech concerns, whose names on their signs out front, many with an x or two, give no indication of what is being done inside.

.

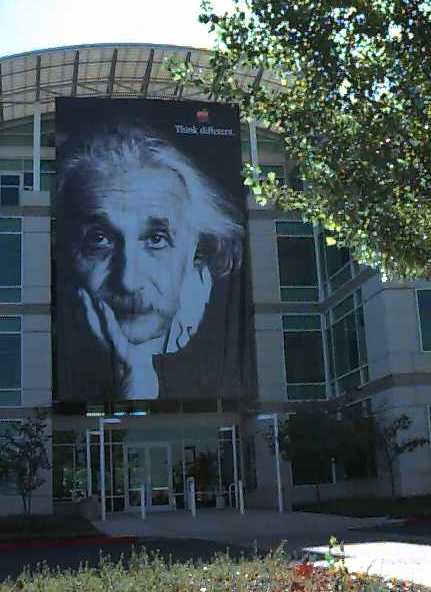

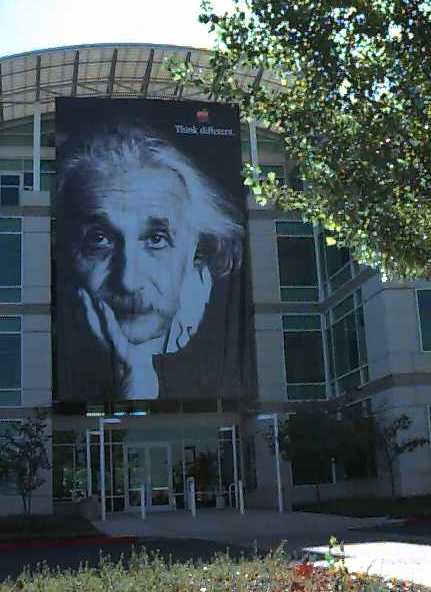

Once, on the Apple main building, visible from 280, a huge picture of Einstein appeared, who exhorted us to Think Different.

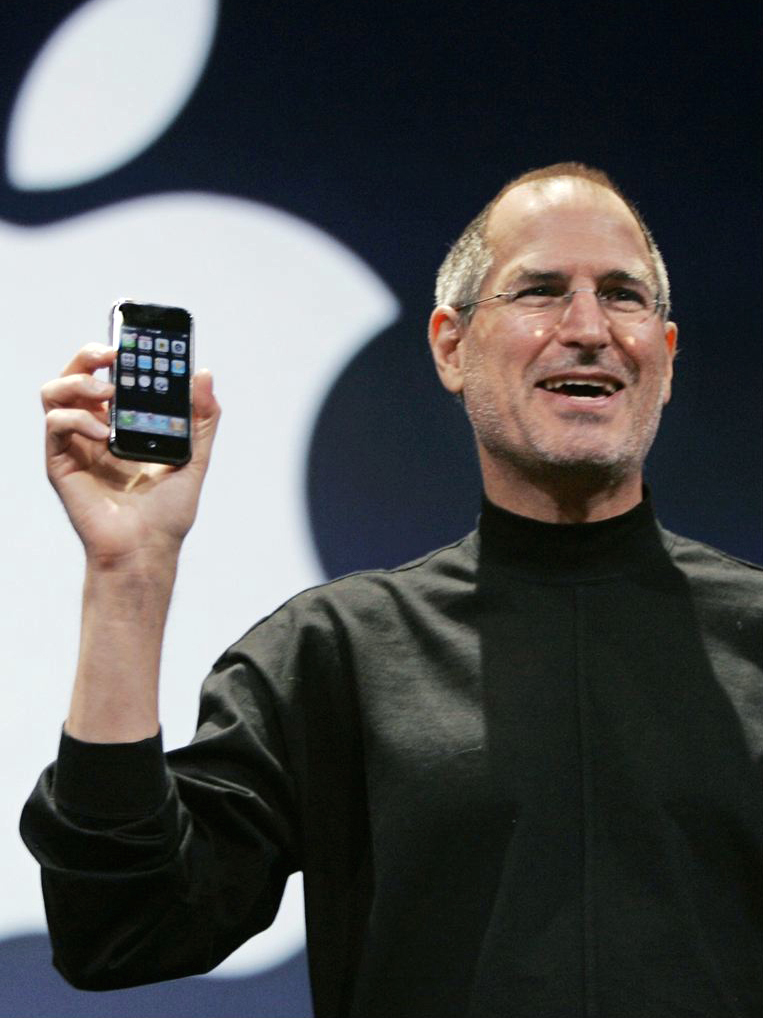

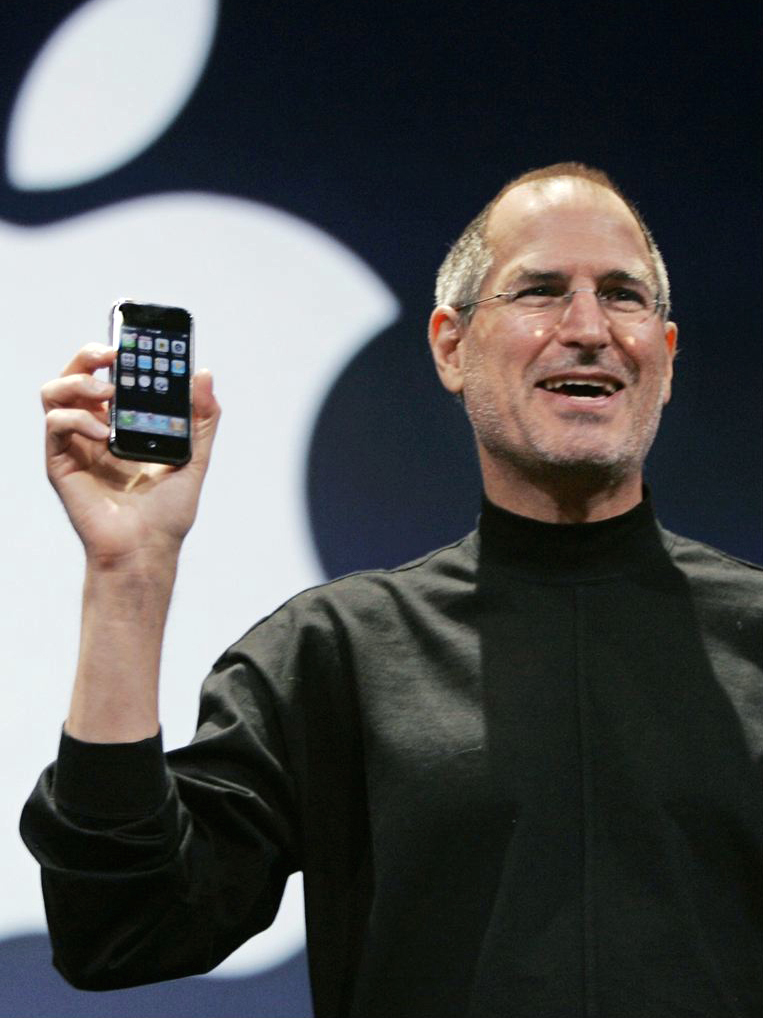

It is unlikely you would ever see Steve Jobs on the street, but he makes iconic appearances in newspapers, online, elsewhere, everywhere it seems.

Saint Joseph of Cupertino, the Italian saint after whom the town was named, could spontaneously rise in miraculous levitation or fall into trancelike states.

.

So I started reading—overviews, basic guides, books on the industry, inside looks. I even learned a little programming, Pascal, C, and C++. Ethnogenesis is the process of creating a new culture, and in Cultures@Silicon Valley J. A. English-Lueck, an anthropologist at San Jose State, studies ours. Our dominant institutions, she tells us, are the corporations and networks; our heroes, the technological wizards; our chief values, efficiency, innovation, and entrepreneurship. She interviewed one former employee at Apple, who said:

Being in Silicon Valley, it’s part of a culture of people who put their heart and soul into their jobs. . . . [It] seems to be more socially conscious. . . . [Y]ou think about how the place you work affects the community or affects the world. . . . When I first [worked at] Apple, we felt we were changing the world. At Apple you definitely have the feeling that you impact people’s lives.

.

The bookstore is gone. The stationery store is gone. If I need envelopes to mail manuscripts, I have to drive five miles one way; Christmas cards, five miles another. I buy books online. The story of a Friday night often is that I decide to go to a small restaurant I once knew only to find it gone as well. My supermarket of some seven years has closed down, and last week I found my gas station being demolished. The WaMu branch bank around the corner, needless to say, is gone. All that is constant about Cupertino is the rate at which it disappears. I take my words from Joan Didion’s essay on what it was like where she once lived, Sacramento.

McDonald’s, Target, Home Depot, etc. don’t count..

.

The Apple headquarters at 1 Infinite Loop, just off De Anza Boulevard and before 280. I used to go to the Apple Store there to see the latest. It reminds me of the sparse, modern architecture you see in sci-fi movies where it appears the future has brought peace and order but something is not quite right.

.

During the dot-com boom, everyone seemed to have a plan for something, even those of us who weren’t in the trade, and throughout the Valley there was a lightness in the air—an uplifting, a looking up—that didn’t come entirely from the desire for cash. You could see someone with hopeful eyes walking down the street carrying a portable whiteboard. Other hopefuls met in empty offices and sat on folding chairs. The community college offered courses on how to program and manage stock options.

At one of my son’s Little League games, I started talking to a father who had a project in mind and was looking for someone to write the proposal. I met several times at his house, in his living room, which had been cleared to make space for a whiteboard and a large slab table where we sat. I read a few books and realized his project wouldn’t work. I’d like to tell you about it, but I signed a nondisclosure agreement. He was a nice guy, and I liked him. I don’t know what happened to him, though.

With the dot-com bust, startups went under and large firms grew larger, those that survived. Programmers started showing up in my classes, bright, optimistic guys looking to start new careers. I liked them, too, and got some ideas for my novel.

I don’t know what happened to them either.

Latinos gather early morning in front of the Home Depot looking for day work, the look on their faces menacing and expectant.

.

We have been through one major earthquake—our chimney snapped—and numerous others I don’t always feel. The state has gone through a series of tremors itself, budget crises of varying degrees. I’ve forgotten how many. As goes the state, so goes my school. For us, hiring freezes, course cancellations, pay freezes, program cancellations, benefits put on hold, even during the boom—the money didn’t reach us.

A classroom at my school.

But during downtimes, more students come to school and its energy rises. There is a renewal of purpose, at least for a while. A degree is their best shot at a better life, perhaps their only one.

I’m still a part-time instructor.

.

Within a ten minute walk from where I live, there are a half dozen title companies and just as many after-school enterprises—”Little Genius” comes to mind. The two are related. Our schools are good, everyone says, and our school district borders are known around the world and in every real estate office and apartment complex in town. So property values have held, the population keeps growing.

I once had an absentee neighbor whose parents rented the apartment for their daughter so she could have a Cupertino address. It amazed me anyone had that kind of money. But also small apartments are crowded with whole families so their kids can get a shot at our schools as well.

My son’s high school, where math and the sciences are pushed, boasts of its placement into Stanford, into Harvard, into the increasingly competitive UC’s, students on the way up and elsewhere.

In a survey taken there 80% of the students admitted to cheating.

A colleague of mine, now at Stanford, started a program called SOS—Stressed Out Students.

My dominant impression of my son’s years in the public schools is of paper—green sheets, assignments, worksheets, fill-in-the-blanks, study guides, outlines, exercises, packets, folders, schedules, and planners—an unending stream. Paper found its way all over our place. I did my best to help him but got headaches trying to keep track of all the procedures.

Process—

.

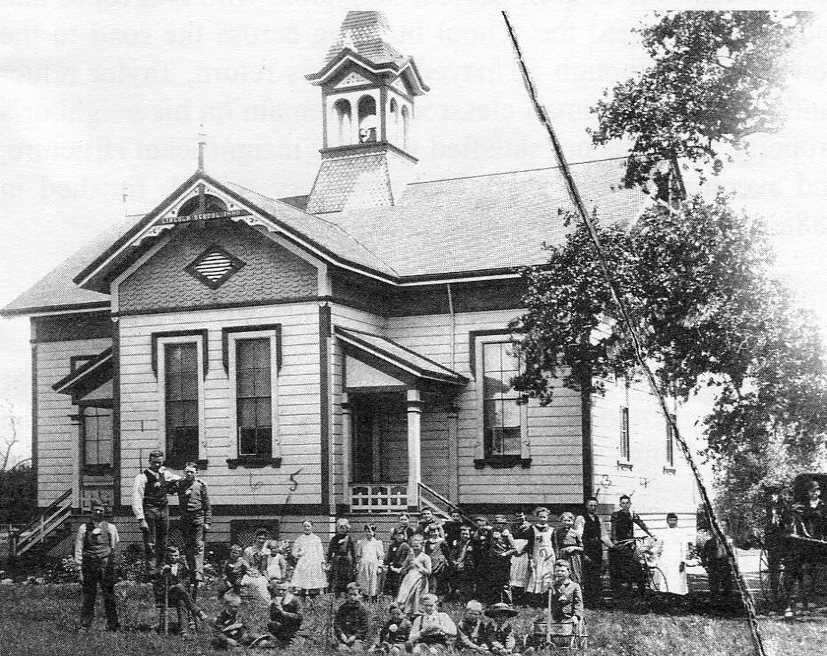

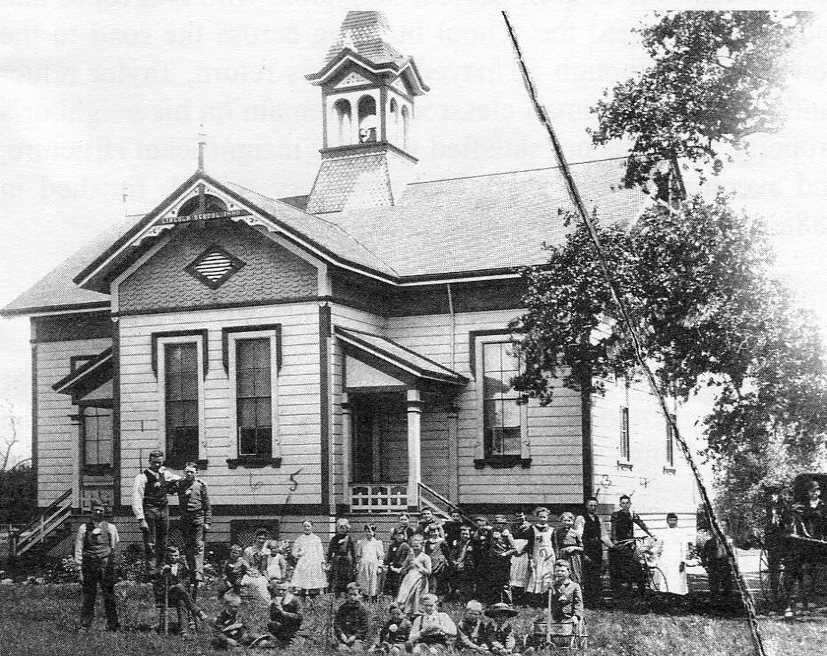

The town does have history. For example:

And:

And:

And:

Monday, March 25. I said Mass. We set out from Arroyo de las Llagas at quarter to eight in the morning, and at four in the afternoon halted at the Arroyo of San Joseph Cupertino. . . . Along the way many Indians came out to us. On seeing us they shouted amongst the oaks and then came out naked like fawns, running and shouting and making many gestures, as if they wished to stop us, and signaling to us that we must not go forward.

From Petrus Font’s diary of Don Juan Bautista de Anza’s second expedition, March 1776.

But almost nowhere in Cupertino can you find a structure, a visible sign, that remains from its past.

.

The center of Cupertino is defined by the crossing of Stevens Creek and De Anza Boulevards. On opposite corners, two gas stations. Behind the Chevron, a shopping center where the stationery store once was, that space and others still unlet.

On another corner, East West Bank; across from it, Cupertino City Center. I had heard about Cupertino City Center before and certainly driven by, but knew nothing about it and had never walked around. But I did that recently one Saturday, walk around the center, trying once more to find out something about what it’s like where I live.

More sparse, modern architecture, a complex of more office space and apartments and a hotel and a few restaurants, maybe something else. I wanted to find out more, but the Center was deserted. The one guy I saw and stopped couldn’t answer much.

There is nothing to do in the center of Cupertino at night.

I do not know the name of our mayor.

I almost never run into anyone I know anywhere, especially students or colleagues. Not many of them can afford to live here. (After the divorce, my son and I moved through a series of apartments.)

My most frequent and most intimate connection with the town and its people still is on the major streets, Stevens Creek and De Anza, six lanes each, usually crowded, and with all the stoplights, stop and go. Quite crowded after work, and driving then is edgy, a little risky.

People are generally friendly, though, once you get out of the car.

.

There are neighborhoods in Cupertino, many, though they are always quiet when I bike around. You have to search to find life, and for me it was Cupertino Hoops, a basketball league for grade-school kids. That’s my son with the ball, left and right. Saturdays they would run two games in a high school gym side by side, all day, both courts filled with ten kids running up and down, shooting, missing, hitting, following imperfectly, with hesitation, with abandon the coaches’ plans, and there would be more kids on the benches, waiting, and parents in the stands, watching, everyone shouting, a daylong release for all of us from what the past week contained, a release for me into a rare joy. . . .

.

In my novel, the narrator, a programmer, lands a job at Summit, a large outfit in a fictional town that, not surprisingly, resembles Cupertino. He works all hours at breakneck speed on a botchy network system, also called Summit, coding quick fixes as Summit tries to steal the march on their rival. The campus, as I say, is charged with wonder and the tension from all that is left unsaid. Then he goes off campus with a dozen others to a small office on Bubb Road where they write a new system called Summix, which they build on Unix, this time getting it right.

I’d like to tell you more about his life there, but Summit went under a year later.

.

Steve Jobs on Kindle:

It doesn’t matter how good or bad the product is, the fact is that people don’t read anymore. Forty percent of the people in the U.S. read one book or less last year. The whole conception is flawed at the top because people don’t read anymore.

But then we got the iPad.

.

It is difficult to get my students to move to abstractions or talk about values and ideals. Their working definition of ideals, from what I can gather, is that they are notions that might be desirable but also are flakey, thus are suspect, at any rate are unattainable. Reality is whatever the world throws them at the present moment. There doesn’t appear to be any connection between the two.

.

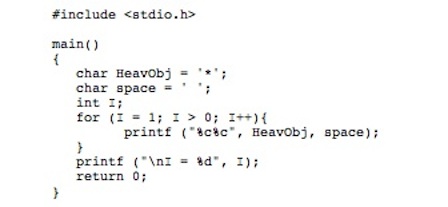

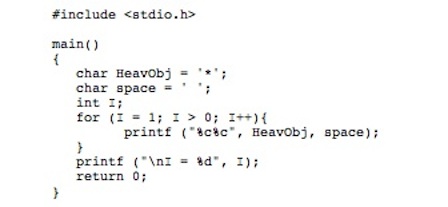

This is a program I wrote in C language designed to create heavenly objects—stars (asterisks)—in a void. The program, in fact, contains an infinite loop, code that asks the program to repeat a process but doesn’t call for an end to that process, so it creates stars, theoretically, endlessly. When the output screen fills with stars, the screen refreshes and causes the stars to *blink*. I have received various interpretations as to what would happen if the program were allowed to run long enough, how long it would take the system to crash.

.

Cupertino does have parks, though they are lightly used, but almost no other open spaces. So it is surprising to still see a field at the corner of Stevens Creek and Tantau, with tall weeds and strewn trash, with No Trespassing signs and signs prohibiting dumping in four languages, that has been vacant all the years I have lived here. It is a toxic superfund site, whose soil was contaminated by leakage from two semiconductor plants, both long gone, of organic solvents including trichloroethylene, trichloroethane, tetrachloroethylene, trichlorofluoroethane, and dichloroethylene.

It may prove to be our most enduring landmark.

.

Actually I live in San Jose now, about 50 feet away from Cupertino and not much further from Saratoga. It’s hard to know where you are in Silicon Valley by sight because the towns run together and there’s little visible difference. I moved to my current apartment because it was quieter and cheaper. I had to go to a special meeting at the school district office, however, and make an appeal to let Christopher finish at the same high school.

But I feel fortunate because a creek runs behind my place, and outside my windows I see mostly trees. The creek and land around it are owned by the city, thus the trees are protected. Not many have this view.

One spring, after a winter of especially heavy winter rains, there was an explosion in the frog population around the creek, tiny tree frogs, I think. At night the sound of their collective croaking—there must have been hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousands—was loud, incessant. . . .

—Gary Garvin

.

Notes:

Satellite photos from Google Maps.

“Think Different” picture from Noah Price, http://www.theprices.net/apple/think.html

Steve Jobs picture from Computer History Museum, http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/steve-jobs/

San Giuseppe da Copertino si eleva in volo alla vista della Basilica di Loreto from Wikipedia Commons.

J. A. English-Lueck, Cultures@Silicon Valley. Stanford University Press.

Joan Didion, “Notes from a Native Daughter,” Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Pictures of Lincoln School, the Kings Daughters Society, IOOF, and excerpt of Petrus Font’s diary from Cupertino Chronicle, published by the California History Center, De Anza College, 1975.

Steve Jobs on Kindle: from “The Passion of Steve Jobs,” The New York Times, January 15, 2008 (http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/15/the-passion-of-steve-jobs/).

All other photos by the author.

.

Gary Garvin lives in San Jose, California, where he writes and teaches English. He has written two novels, and his short stories have appeared in Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and another novel.

.

.

San Diego sunrise from my bedroom.

San Diego sunrise from my bedroom. Point Loma

Point Loma Ocean Beach Sunset

Ocean Beach Sunset Marine Corps Recruit Depot

Marine Corps Recruit Depot

But before that—twice, in fact—you decide it will be fine to give birth without drugs—since there is no anesthesiologist or surgeon on your island. The first baby is born on a table at the local hospital with the crazy mid-wife telling you not to push and the Victoria helicopter team on hold on the telephone. The second one is born with the calm and wise midwife, the one you wanted the first time. The baby arrives on a Friday afternoon on the floor of your bedroom, right where your husband tends to pile his dirty clothes. Because you spend most of your labour in the bathtub, you thereafter find taking a bath with his real live body in your arms, in the same tub, an extraordinary and humbling thing. This, you think, is why people stop moving. This is why they find a home and stay in it.

But before that—twice, in fact—you decide it will be fine to give birth without drugs—since there is no anesthesiologist or surgeon on your island. The first baby is born on a table at the local hospital with the crazy mid-wife telling you not to push and the Victoria helicopter team on hold on the telephone. The second one is born with the calm and wise midwife, the one you wanted the first time. The baby arrives on a Friday afternoon on the floor of your bedroom, right where your husband tends to pile his dirty clothes. Because you spend most of your labour in the bathtub, you thereafter find taking a bath with his real live body in your arms, in the same tub, an extraordinary and humbling thing. This, you think, is why people stop moving. This is why they find a home and stay in it.