L

ouis Armand’s fiction saunters through the darkest underbelly of society, illuminating the forgotten and the discarded. His recent novel Breakfast at Midnight (2012) reads like a twisted, brilliantly savage acid noir: amid a decaying Prague, rechristened Kafkaville, a quasi-mystery unfurls through the addled mind of a nameless fugitive, a man looking to solve a murder and piece together his own history. Canicule, released this past April, finds purchase through the lens of cinema: a man commits suicide, forcing his friends—failing screenwriter Hess and terrorist-sympathizer Wolf—to reenter each other’s orbit. A narrative revealed in snippets—“I’m not able to put the pieces back together, because I don’t understand them,” Hess confesses. “They’re pieces of an alien life, a completely alien life.”—the novel’s elasticity feels like an experimental film, spliced together on a dusty Steenbeck. Constantly moving forward and backward in time, Armand refuses to coddle his audience, and the result is a tale full of irony, repetition, and alcohol-fueled remorse.

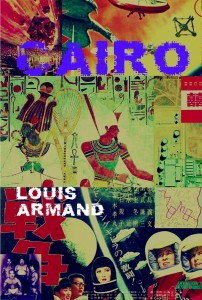

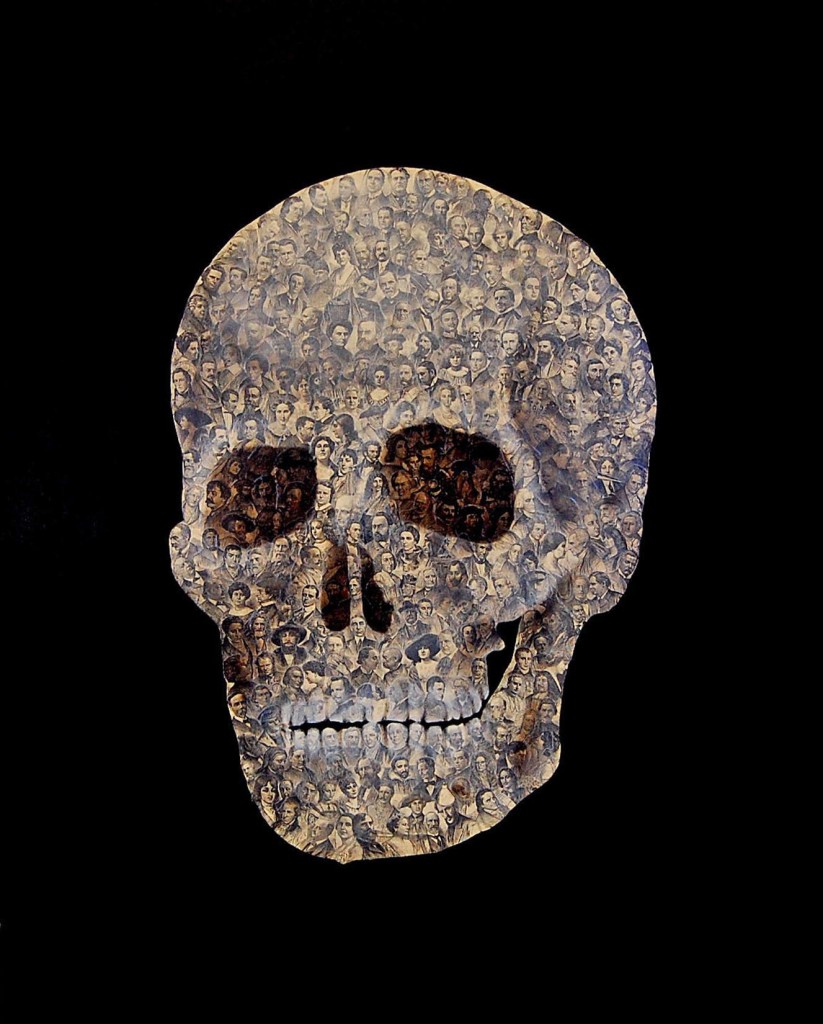

Now comes Cairo. Set for publication in January (Equus Press), the following excerpt fuses themes and beats from Armand’s earlier novels: a murder, followed by a mystery left for men out of their element to decipher. Cinema bubbles throughout, as well, as Armand’s characters employ film tropes to handle their increasingly odd situation. And yet, while these ideas resurface, Cairo’s aura is nothing like that of Breakfast and Canicule, for while those settled on a far more serious plain, Cairo is downright playful. What makes this excerpt so very interesting is that it showcases Armand’s gift for language, both in his wickedly funny character exchanges and in the way he describes locations: senses are explored, filling us in on not only the tangible space, but also its sonic properties, its perfume, truly creating in three dimensions the underbelly of the underbelly.

— Benjamin Woodard

ELEPHANT’S EGG

T

he East Ham Mortuary off Barking Road was a squat cube of dark brick with a set of blue doors at the entrance. Nicky Cohn was waiting under a yellow CCTV sign, collar up, cigarette drooping from the corner of his mouth, somehow still alight in the drizzle, when Joblard wheeled up riding the clutch. A naked fluorescent blinked over the doorway, lending the journalist’s features a decidedly funereal cast. The light glistened on the wet chrome of the BSA’s petrol tank, catching the steam as it hissed up from the single cylinder. Then it didn’t. Then it did.

“You’re looking bright and chirpy,” Nicky Cohn said as Joblard yanked off his helmet, face a blur behind frozen breath. “Not half bloody cold.”

“Nice night for it alright,” Joblard said, “though I’d rather be in the back lounge getting intimate with a pint. You been in yet?”

“Nah, just got here. Thought I’d have a fag before trying to blague my way past the Homicide and Serious Crime boys. I recognised two of them when I peeked in through the door. They can be right cunts when it suits them.”

Joblard stuffed his gloves inside his bellstaf jacket, helmet under one arm.

“That’s good, I could fancy a couple of cunts on a night like this.”

“Not like these you wouldn’t. Speaking of which, what’s your Spielberg up to these days?”

“You on the square brother?”

“Eh?”

“Freemasons. Grand Lodge. He’s got some notion about poking a camera into the holy of holies. Ladies of the Illuminati.”

“The what?”

“Yeah, I reckon our mate Johnny Fluoride might’ve been getting him some of the more candid stuff. Kind of spank-and-tell exposé of the secret handshake brigade.”

“Tell me about it after,” Nicky Cohn said, tossing the unsmoked half of his cigarette on the ground. “I’m freezing my balls off out here.”

Behind the blue doors was a corridor and an office with a little window where Nicky Cohn showed his press credentials and signed in. Joblard took in the atmosphere. A couple of plods eyeballed him from where they were sitting beside a pair of swing-doors, like they were on stakeout duty waiting for a corpse to show up and trying to outguess each other about whose it might be. Joblard grinned at them. It was a rule he had with cops: you never break eye contact and always smile, drives the fuckers nuts. Nicky finished with the forms and they waited for a technician in a blue smock to come and give them the grand tour. He was a tall and skinny, with a straggly goatee and hair down past his collar and acne on his neck. Student-type. Taking full advantage of the opportunities society had on offer.

“This way gentlemen,” he said, taking a chit from the receptionist behind the window. “My name’s Zack and I’m your guide for this evening. The main attraction’s just through here and on the left.”

They ran the gauntlet of the two Homicide boys, busy giving Joblard the business with their cop stares, tongues working the backs of their teeth, but not making any more than a show of it.

Joblard jerked his thumb back at the swing-doors, behind them now as their guide steered them left along an underlit tunnel of half-tone green:

“What’s with the local entertainment, Zack?”

“One of our residents has attracted special attention.”

“Zack,” Nicky said, “I have a confession to make. That’s who we’re here to see.”

The technician stopped and scrutinised the chit he was holding.

Joblard, trying to get a look at it over the technician’s shoulder, found himself with an unobstructed view of a dandruff condition on the verge of spiralling out of control. Greenish flakes of dead scalp layered the back and shoulders of Zack-the-mortuary-technician’s smock, sifting down between greasy cords of black hair. Joblard edged back to maintain a safe interpersonal distance. Dandruff always made him think of leprosy. It was an association he’d had ever since childhood and the smell of antidandruff shampoo in the change rooms. Afraid he’d catch the stuff. At least they’d had the decency to wash. Some people, he thought, ogling the back of the technician’s head, lack the very basics of self-respect.

“You’re not here to see 856?”

“No.”

“We’re supposed to report anyone who wants to visit the new guy.”

Nicky slipped a freshly minted portrait of Queen Liz into the pocket of the technician’s smock.

“Put this towards your scholarship fund, Zack. No-one ever need know. You just got the numbers mixed up, that’s all.”

Zack glanced at the bill, which in the light of the corridor was the brown of a freshly minted turd.

“She looks kind of lonely, don’t you think? Got another one of those to keep her company?”

Nicky slipped the technician another royal likeness. The kid grinned.

“Right through here then, gents,” Zack said, leading the way.

Once when he’d been KO’d in the ring by the southpaw Mickey “the Hammer” Mulligan, Joblard had woken up on the floor staring at a light thinking he’d died already and was stretch out on one of those mortuary slabs they have in movies and any minute some geezer in a white labcoat was going to come in and poke a scalpel in his brain and pronounce the cause of death. Telling himself how “Hammer” wasn’t a name Mulligan earned in the ring but operating a protection racket off Brick Lane. But the room Zack the technician ushered them into wasn’t like anything in a film, more like a wholesaler’s stockroom. The far wall was lined with time-warped refrigerator doors you’d expect to find racks of frozen meat behind. Sides of beef, lamb, pork. A whole raffle bonanza.

The technician went straight to the third door down and yanked it open. Behind it there were three more doors, square, one above another, old paint a dozen hues of off-white cracked and flaking. Johnny Fluoride had taken up residence behind the door third from the bottom. Like those Japanese coffin hotels. Zack trundled out the slab. Joblard shivered. Johnny Fluoride’s body, sans head, was wrapped in semi-opaque plastic. The swim hadn’t done him any kindnesses. Even with the plastic on he looked terrible, like he’d been force-fed through the proverbial wringer. But whatever took his head off, that sure as hell hadn’t beaten around the bush.

“Jesus!”

The corpse, Joblard duly noted, had bare feet. Eventually, he supposed, the Coroner’s Office would release a report. He wondered what they’d make of the fact Johnny here had gone swimming without his boots on. Getting a head start, so to speak. The violent crime boys hadn’t made a positive ID yet. Their floater had washed up not only sans head but sans anything in his pockets. According to Nicky’s mate at the yard, Johnny Fluoride’s body had still been zipped into his army surplus when they found him. Which was how he knew it was Johnny Fluoride. The anorak had somehow kept him afloat, otherwise he mightn’t’ve turned up at all till next week, if ever.

Still, Joblard supposed, it’d only be a matter of time now before the Homicide boys rang the old widow’s doorbell over in Greenwich and got themselves an earful. And then from Greenwich to Canvey, which was all they’d need to put him on the spot. A knock on the door in the middle of the night. But at that moment, all Joblard could really think of was how the fuck…?

The three of them stared at the body for a while in silence. Nicky flicked at the chipped paint on the freezer door. The room seemed to Joblard to’ve grown noticeably colder. Nicky pulled a splinter of old paint from under a fingernail and held it up to the light.

“You know,” he said, breaking the silence, “they reckon lead paint’s accountable for half the violent crime on the planet. God’s truth. But just try telling that to the Homicide boys. And the people responsible for the stuff? Why, only the honest-living folk at Innospec, up on the Manchester Ship Canal, flogging tetraethyl lead wherever it hasn’t been banned yet. Fun places like Burma, Iraq, Afghanistan, North Korea. The fact it’s illegal to sell in good old Blighty doesn’t mean they can’t manufacture and export the stuff. Now if it was anthrax…”

“Somehow I don’t think it was lead paint did that,” Joblard said, pointing at the mess where Johnny Fluoride’s head formerly resided.

“The interesting thing,” the technician said, fingering the tag affixed to the big toe of Johnny Fluoride’s right foot, “is they found river water in your man’s stomach, but not in the lungs. Whoever blew his head off gave him a soaking first. Must’ve had something they wanted. That’s my guess. Held his head under till he talked. Then pop. No further use. Seen it before. The Albanian they found in a suitcase last year? He’d swallowed half a gallon of Thames water too, and not from any tap. Except they used a saw on him instead of a canon. Never found the head, either. Your mate involved in any funny business, then?”

“Nah,” Nicky said. “He ran nostalgia tours for old pub-rock fans. Didn’t know shit from clay. Probably a case of mistaken identity.” Turning to Joblard: “What do you reckon?”

“Yeah, mistaken identity,” Joblard echoed. “Poor sod.”

“Did he have a name?”

“Mmm,” Nicky said. “Can’t remember.” To Joblard: “D’you remember his name?”

“Frank maybe? Don’t rightly think he ever told us.”

“Too bad,” Zack said. “Too bad.”

…

A wedge of lemon floated in the glass of water Nicky Cohn was holding up to the light, eyeballing the citrus bits drifting around in it. He’d watched the waitress closely while she filled the glass straight from the tap.

“That stuff comes direct from the river, you realise?” Joblard said, trying on the tone of voice of someone attempting to be helpful. “If you’re lucky, there might even be a couple of particles of Johnny Fluoride in there. Not to mention all the other crap they dump in the Thames. London’s Pride.”

Nicky Cohn snorted and set his glass down in front of him. The bar they’d retreated to from the East Ham Mortuary was slowly filling up for the evening with what looked like a regular crowd. Joblard counted at least a dozen different types of Adidas tracksuit. The only beer they had on tap wasn’t beer at all but some foreign crap called Carlsberg, so he’d settled for a cup of tea. The publican had given him one of those looks. The de rigeur TV in the corner was running the day’s Ashes highlights. Depressing viewing. They’d’ve done better switching to one of the disaster channels. BSkyB or whatever. Rapping out the small print on why the world was going to shit. Global warming conspiracy nuts. The latest candidate for World War Three.

On cue the box cut from the cricket roundup to the news desk. Some joker in a flash suit talking to himself in a studio with lots of high-tech graphics making up the décor. Lip-syncing to a soundtrack that’d been swapped for the usual pub banter in competition with some sort of Kylie Monogue remix. Text scrolled across the bottom of the screen. Then cut to footage of what looked very much like riots on Wall Street. Archive material on the Twin Towers going down. Joblard registered crowd shots and helicopters. Something brewing on the other side of the pond, he thought. Nicky Cohn was still eyeing his glass in a manner you might describe at pensive.

“Gone to a better place, if you believe that stuff,” Joblard offered, thinking condolences of some sort might be in order. Though exactly what Nicky’s connection with Johnny Fluoride was, he didn’t know. Nicky looked up from his glass at the bulge Joblard’s gloves made inside his jacket.

“Your tea’s getting cold.”

“Don’t really fancy it anyhow.”

“My mum used to say cold tea’s good for piles.”

“That right?”

“She made my old man drink the stuff till the day he died. Sure enough, never did get piles. Fucked his liver good and proper though.”

“Eh?”

“Used to slip rum in the tea to make the stuff drinkable, when the old girl wasn’t watching. She’d keep a pot cooling on the windowsill for all occasions. Earle Grey. By the time he finished his third cup of an evening, the poor bugger could hardly stand up. Which the old girl attributed to the tea’s potent medicinal effect.”

Joblard sniffed his cup then set it back down on its saucer.

“Just regular tea, this. Probably doesn’t work.”

Nicky squinted up at him.

“They put out a call for witnesses. A couple of those lugs might want to have a talk with you. Canvey jetty. How many people saw you together?”

“Just the barman. And maybe this scarecrow character with some sort of skin disease on his face.”

“Mmm. Barman’ll probably just mind his own business, unless they make a point on it. Who’s the scarecrow?”

“Dunno. Followed me, though.”

“Followed you?”

“Yeah, him and a dwarf. They both followed me when I went over to Johnny Fluoride’s gaff. After the shithead decided to take a swim. That’s the bit I can’t figure out.”

“Dwarf?”

“Former associate of our headless friend, I do believe. Seems Johnny accidentally snapped a pic of him and he didn’t like it. Kind of, in flagrante delicto, as they say.”

“You’re not making much sense, old chum. Care to fill in the blanks?”

Joblard, against his better judgement, took a sip of the tea. Grimaced. Resisted the urge to spit it back out.

“Disgusting.”

“Like I said.”

Joblard wiped his mouth on his sleeve, pushed the cup and saucer aside, then folded his arms.

“Bludhorn paid Johhny Fluoride to take some candids. Some geezer getting his jollies being tickled with a riding crop. High class stuff. In the middle of which, this dwarf turns up, blows the geezer’s head off. On film.”

“Kosher?”

“One hundred percent.”

“So Johnny was tied up with Bludhorn, too, eh? And that’s why you were out on Canvey? Because of these pictures?”

“Except I never knew anything about what was in the pictures till after.”

“And I suppose Bludhorn has them safely under lock and key?”

“Curious are you?”

“Curious, old chum, is hardly the word.”

“Doesn’t look like you’re the only one.”

“You think whoever nixed Johnny might be after the pictures?”

“Stands to reason, doesn’t it? Besides, I spotted scarecrow and his mate hanging around Bludhorn’s club in Soho.”

“Maybe we should give the old bugger a call.”

“Maybe.”

“Got anything better to do for the next five minutes?”

Joblard creased his brow like someone trying hard to think, glanced sidelong at his teacup, then fished his mobile out of his inside pocket. Nicky Cohn looked at him in disgust.

“Knowing how you hate these things…”

“You’re begging for cancer of the brain, you realise that?”

Joblard grinned, fingered the keypad, stared at the screen. The background noise covered the dial tone, but a little icon on the screen indicated that the phone at the other end, Bludhorn’s, was ringing. Joblard had counted to five when the icon was replaced by a message saying his call had been interrupted and please try again later.

“Not answering?”

“Nope.”

“Mmm. You know, this could be one hell of a story.”

“Could be. Could also just be a coincidence.”

“Come off it. Why the heck’d anyone go to the trouble of saving a clown like Johnny Fluoride from drowning just to blow his head off?”

“Beats me. Maybe he washed up all by himself, emptied his own pockets, then blew his head off just for the hell of it. Or maybe he got sucked into another dimension. Dr Who stuff. And his head’s still on the other side, mashed into the vortex. One thing I do know, he was scared shitless of somebody. Said they were out to get him. Thought it was because he saw something he wasn’t supposed to see and they found out about it. Or maybe they wanted to send a message further up the line. Join the dots, you know, so whoever arranged to take the pictures in the first place’d get the connection. So they’d know not to fuck with it. Masonic conspiracy stuff, maybe.”

“Is that what Mr Undertaker says?”

“Bludhorn knows who the geezer is but he’s not saying. In the pictures you can’t really make out his face. There’s just this geezer tied to a chair getting whipped. Stiff upper-lip type. Then there’s a flash. Next thing the dwarf appears out of nowhere and the geezer’s head’s vanished. Just like that.”

“Too bad.”

“Hey, did you hear about that coke-dealer, blew some kid’s head off in Wapping last night?”

“Twelve gauge? Yeah. Sodomised the corpse. Made a real mess of himself afterwards, too. Think there might be a connection?”

“You never know.”

“Nah. It’s too crazy. The lunatic shot himself in the head.”

“What if it only looked that way and someone else shot him in the head?”

“Nah.”

“It’s a possibility.”

“Shit. That’d make four. Four headless fucking corpses in one day. One of whom we don’t know anything about. It’s too much.”

“Don’t forget the tart with the whip. If she copped the same treatment, that’d make five.”

“Five? I don’t buy it.”

“Why not ask your mate to scan the register. See if anyone else’s checked into a morgue lately without their head attached.”

“Bodies could’ve ended up anywhere. In a bleedin’ meat factory, for all we know. Fed into a mincer. Bzzzz. Like they keep finding horse DNA in beef paddies. What if it was human DNA instead? Soylent Green stuff. Kid munching on quarter-pounder spits out a couple of fingernails. Not the sort of thing they’d want to see on the six o’clock news. Imagine it. Wozzie the Cannibal Clown! Bad for business.”

“I’ll stick to being vegetarian.”

“You could do far worse, chum. Say, what’re the chances you can actually find this dwarf character?”

“Dunno. All look the fucking same to me. I was figuring they’d probably show up again by themselves. Unfinished business. You know Bludhorn’s got a thing about midgets?”

“Size.”

“Eh?”

“It’s all about size. Midgets. Small.”

“I know what a fucking midget is.”

“Same reason they go for the oriental girls, you know. Little hands.”

“What’re you talking about?”

“Nothing, chum. Over your head.”

“There’s a freak running around blowing people’s heads off and you’re on about some slanty tart’s manicure?”

“A dwarf. Blowing people’s head’s off. Apparently connected in some way to your Mr Undertaker. Capische?”

“What’s that mean, then?”

“What’s what mean?”

“Capische?”

“Don’t you watch films?”

“Not those sort of fucking films I don’t. You want to have a conversation with fucking subtitles, go to fucking Poland.”

“Maybe the dwarf’s fucking Polish, you ever consider that?”

Joblard blinked, looked thoughtful, creased his brow. Nicky Cohn shook his head, muttering to himself. He sniffed at his glass of water, took a sip.

“Oh, and I forgot to mention,” Joblard said, “they were driving a smartcar.”

Nicky Cohn peered over the rim of his glass, set it carefully on the table, picking a sliver of lemon seed from is lip.

“What?”

“You know,” Joblard said, “one of those poxy little jobs, like a golf buggy with an M.O.T.…”

Nicky Cohn made a sucking sound with his teeth, poking his tongue up under his lip.

“I’ll tell you something, chum,” Nicky Cohn said, straightening his mouth out. “If I hadn’t just seen Johnny Fluoride’s headless corpse with my own eyes, I’d swear you’re flaming nuts.”

…

Back during what used to be called The Troubles, old Uncle Hugo, ex-Sandhurst, had the good fortune to spend a tour of duty behind eight inches of plate glass in a pillbox in the fair city of Armagh. He’d been standing there one day watching the drizzle slowly mutating from bad to worse when some Fenian fucker, parked on a hillside a mile away, took a pot-shot at him with an elephant gun. He’d seen the shell embed itself three-quarters the way through the glass, big as his thumb. When he told the story afterwards, he’d always joke that if there’d been a tailwind, the bullet would’ve caught him right between the eyes. And taken his whole bleeding head off.

Joblard had been thinking of Uncle Hugo’s story while he watched the helicopters circle the Shard. It looked like the flattened head of an enormous glass prawn, sticking up above the Canada Square towers. Some Mujahadin types had tried to blow it up a week ago and now they had half the RAF up there every night at tax-payers expense, searchlights criss-crossing the rooftops. Every wisearse on the South Bank was probably laying bets on how long it’d be before some trigger-happy Afghan vet in a chopper went bezerk and did the job himself, like the one that smacked into the crane over in Vauxhall. Maybe blame it this time on a meteorite.

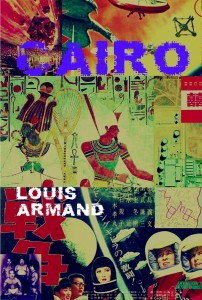

What killed Uncle Hugo in the end was a brain tumour. “Size of an elephant’s egg,” he’d say, while the nurse prepared his bed-bath. “Elephants don’t lay eggs, Captain Banks,” the nurse would tell him. “This one did.” And that, as they say, was the end of the matter. Joblard remembered the picture the doctor showed his mum. You could see the skull and what he supposed was brain tissue with a void right in the middle of it. Like that Fenian bullet had a bad karmic vibe that’d lodged in his uncle’s head and grown there for forty years into a knot of dead cell tissue, invading whole swathes of cortex till his motor neurons finally packed it in.

Joblard had tried calling Bludhorn once more after leaving Nicky Cohn, but the proverbial Undertaker still wasn’t picking up. Piss-taker, more like, Joblard thought. If things keep the way they’ve been going. He decided to swing by the Hindu’s hole-in-the-wall for a bucket of soy Vindaloo, papadums and sweet mango. Then back to the Fridge. Upstairs one of the regular parties was in full-swing, sub-sonic bass shaking the windows in their frames. He killed the engine and wheeled around to the service lift, chained the BSA to the grill and hung a tarp over it. The basement lights weren’t on, so he figured Bird Girl probably wasn’t back yet. Decided to go in quietly anyhow, in case she was there asleep. Though how anyone could sleep with that Moby shit playing, he didn’t know.

The basement wasn’t exactly luxurious, but it was big. A single room, about ten yards wide, ran the length of the building, a kitchenette with garret windows at the back. It’d been used once upon a time for storage. Upstairs was where the meat processing had gone on. Some of the residents practiced a type of voodoo to ward of bad spirits, appease the bovine gods. Joblard wasn’t interested in animal karma. The place stank of rat bait. Every other morning he took a bag of dead rats out to the trash. He burned incense. Told Bird Girl there must be some sort of rat disease going around. Had to be careful what he left the bait around in, though, in case one of the resident freaks from upstairs got to scrounging munchies on a comedown.

Joblard left the takeaway by the door, tiptoeing through the basement obstacle course in his boots and trying not to bang his head on any fixtures. The sound of snoring was audible despite the thumping bass. Joblard peered into the bed – a king-size mattress on trestles high enough for a dwarf to camp under. On account of the rats. The bed, though, was empty. The snoring came from the other side of it. Joblard made out something moon-like wrapped in an overcoat, lying on the couch. It didn’t look like Bird Girl. He went over and flipped on the lights. Ol’ Pasty, with his head back, felt hat tipped forward, mouth open, was snoring like a bullfrog. His coat was gathered at the neck in the ball of a skinny fist, blotchy like his face. His other hand was wrapped around the butt of a service issue .45.

By the time the scarecrow got his eyes open, Joblard already had an elasticated ocky strap round his wrists and was in the process of cocooning the bastard with an industrial roll of kitchen wrap. Ol’ Pasty’s eyes bugged. They bugged even more when Joblard shoved the .45 in his mouth and asked him very politely to sit still. Wearing about fifty feet of kitchen wrap, the scarecrow looked like a sick grub. He squirmed when Joblard pulled the gun out of his mouth. It made Joblard think of his first day in school.

“You’re not going to piss on my couch, are you?”

Scarecrow shook his head. His grey felt hat had tipped to one side, revealing a serious case of eczema. It gave Joblard the creeps.

“Where’s your mate?”

Scarecrow just looked at him.

“You’re not fucking Polish, are you? Rozumiesz anglielskiego, ty głupi pizdy?”

Scarecrow glared.

“Suit yourself.”

Joblard tore off a strip of kitchen wrap and somehow got it around the scarecrow’s head without making contact with the eczema.

“Since you’ve got nothing to say,” Joblard pocketed the gun. “Any trouble breathing, just remember to holler.”

Joblard went to the kitchenette and grabbed a six-pack of Guinness from the fridge, then back to collect his vindaloo. He pulled up an armchair by the door and killed the lights, letting his eyes adjust to the gloom. Maybe, after he’d enjoyed a decent meal, he’d get the jumper leads out and see how the scarecrow responded to a little encouragement. Maybe the fucker was mute, hehe. That’d be a laugh. Better him than me.

Outside, the same Moby track was still echoing in the stairwell. There was the sound of the DLR rattling by. The usual peace and quiet. Joblard grinned to himself, spooned some rice into his curry, popped a can of stout and settled back, munching on a papadum, to see what the remainder of the evening might bring.

…

Nicky Cohn was standing in the middle of the room, toeing an orange-and-brown paisley rug Bird Girl had said blended with the couch. Joblard couldn’t help thinking she was right. He spooned some instant into two give-away Wozzie Burger coffee mugs and snapped off the kettle. Poured. Doused the mix with soy milk.

“Sugar?”

Nicky Cohn pulled a face like the very idea appalled him.

“Nice place you’ve got here. Pity about the stiff.”

Joblard brought over the coffee and stood beside Nicky Cohn. They both sipped their coffee, surveying the couch. The scarecrow’s brains had made a complete mess of it. But there was no denying it had a certain affinity with the rug. Little fractalised blobules of red, black and grey floating in a type of Rorschach amber that continued half-way up the wall, punctured by bone shard. Bits of the scarecrow’s brains were even stuck to the ceiling. Joblard thought he recognised a patch of eczematous scalp glued to the lightshade – a paper globe that’d once been white, but now looked like a sepia pock-marked moon. Sea of Tranquillity and all that.

At some point in the night Joblard had dozed off under a dusting of papadum crumbs and pilau rice. What woke him was a sound like rats trying to burrow out through the walls. He’d been dreaming of a boat, somewhere on a river. A sort of funeral barque. Egyptian. Head of a jackal at stern. Anorexis, or whatever it was called. Dog god. With a gold sarcophagus in the middle of it. Like Bludhorn’s museum. Naked midgets at the oars. Ol’ Pasty there, too, beating a big drum. A sail with billowing Rosicrucian eye. And Joblard himself, trapped inside the sarcophagus, gasping for breath, tangled in mummy wrappings, trying desperately to escape.

He spilled what was left of the vindaloo grabbing for the .45 wedged in his Bellstafs, lucky the safety catch was still on. At first he thought the scarecrow had gotten away. The place was quiet. The party upstairs must’ve ended. And then he saw it, a faint mock of paracelene from the back windows glinting on the kitchen wrap, casting a long shadow up the wall. Only it was no shadow…

“What d’you know,” Nicky Cohn slurped his coffee. “Looks like your pal must’ve wore falsies.”

“Eh?”

“Unless those are yours?”

He poked his mug towards a splotch on the back of the couch. Joblard squinted at it. A pair of dentures was embedded in the muck. They seemed to grin back at him.

“Yikes.”

“Think someone’s trying to finger you, old chum?”

Joblard pulled out the scarecrow’s gun. Sniffed at it. Nicky Cohn glanced at him with a vague look of apprehension.

“Hasn’t been fired. Beside,” he held the gun out for Nicky Cohn to inspect, “no .45 on Earth could’ve done that.”

Nicky Cohn demurred.

“Still, doesn’t exactly look good, does it?”

Joblard stuffed the gun back in his pants.

“What’re we going to do?”

Nicky Cohn held out his empty mug, Wozzie-the-Clown smirking sideways from it.

“I’ll take another one of these, if you’re offering.”

It’d been just after four o’clock when Joblard called Nicky Cohn. Figured he slept in his office. Got the answering machine. Shouted something incomprehensible at it. Rang again. Third go, the answering machine cut-out mid-message and the real-life Nicky Cohn came on.

“D’you know what time it is?”

“Of course I know what fucking time it is!”

“This better be good, old chum.”

“What if I told you there’s a headless fucking corpse sitting on my couch?”

He’d made it there in fifteen minutes. The sort of thing possible in London only around four a.m.

“You weren’t kidding,” Nicky Cohn said, when he saw the scarecrow. “There’s a corpse with no head sitting on your couch. What’s he wrapped in plastic for?”

Joblard spieled it out while Nicky Cohn clicked his tongue, shook his head, toed the rug. Sniffed.

“Rat bait,” Joblard explained.

His visitor appraised the room without moving from the spot, keeping an eye out for stray rodents.

“Nice place…”

Handing Nicky Cohn a fresh mug of coffee, Joblard pondered the situation. Nicky was right. If the cops got hold of this, they’d be all over him. Wouldn’t matter what he said. Wasn’t a single alibi he could think of that’d hold water. So to speak.

“In the films,” Nicky Cohn offered, warming is hands around his coffee, “they always search the body first, get rid of any I.D., then put it – the body, that is – in a bin liner and dump it somewhere. Got any of those housewife gloves? You know, for washing dishes and stuff?”

…

“What about his mate?”

And that’s when Joblard knew he’d have to find the dwarf. But even then, none of it made any sense. He’d spent half-an-hour scrubbing the wall and ceiling, scooping bits of brain matter off the floor, then bundling the stiff into a couple of bright yellow bin-liners – the ones they sold cheep at the local Sainsbury’s. The couch was a goner. He tried getting the stains out with diluted bleach. It only made matters worse. Nicky Cohn sat over by the door and watched, throwing in the odd suggestion from time-to-time. Like why not just toss the carpet over the back of the couch and be done with it?

The only thing Joblard had been able to find on the scarecrow was a roll of tenners and a pawnshop ticket. Castle Square, Brighton. He could dump the stiff and get down there on the bike before the place opened. See what he could find out. But the first thing was where to do the dumping. He’d never been all that conscientious about recycling. And riding about with a couple of bright yellow bin-liners on the back of a vintage BSA wasn’t exactly low-key. But then, nothing he ever did was. He figured the best thing to do was drop the lot into the canal, over by Tequila Warf. It was only a block away. Nicky Cohn didn’t like the idea quite so much. It wasn’t the headless corpse that bothered him. It was being a possible accessory that gave him the heebie-jeebies.

“Don’t tell me you’re suffering from a case of journalistic ethics?”

“Do I work for the Sun?”

“Thought you type were all the same.”

“Listen, chum, some of us have a future to think about.”

“What about the poor fucker with his head blown off. You reckon he didn’t have a future to think about?”

“Not sure I get your point, chum.”

“Nicky. There’s a headless stiff on my couch. If we don’t get it out of here, I’m screwed. You think I popped Johnny Fluoride? There were witnesses.”

“I just want to be able to write the story without calling down any heat. My mate at the Yard already smells a rat. Like where I got the tip-off on the floater. This could end up ruining my expense account.”

“Shut up and give me a hand, will you.”

Joblard bundled the disposal job in Bird Girl’s rug and left the stain on the couch to look after itself. Between the two of them they got the rug out into the yard, along the alley behind the Rajasthan Café. Nicky Cohn huffed and puffed at the back while Joblard shouldered most of the weight up front.

“For a skinny bastard, he sure weighs a bloody tonne.”

Once they’d made it across the parking lot off Brunton Place, it was easy going. Trees lined the canal, shrouding it in shadow. Bits of concrete rubble lay piled hither and yon. Bricks. Steel piping. Coiled wire. A body-disposal paradise. Across the water, a billboard stood up from the wharf, facing the Commercial Road Bridge, as if the plan was to get your average out-bound commuter worked up for the homeward run, and the missus-and-three-veg. Miss Big Tits in the Wonder Bra ad. Hello Pikers! Some local vigilantes had sprayed out the offending bits, adding WHORE across Miss Big Tits’s face. The marketing geniuses had really picked their demographic. It wasn’t called the East End for nothing. Any further east, you’d be in fucking Cairo.

“I heard somewhere,” Joblard said, hoisting the weighted bin-liners across the tow-path to the edge of the canal, “that if you cut the guts open, a body won’t float. On account of the gas. When it decomposes.”

“Not much good when it’s wrapped in a plastic bag, is it?”

“Shit. He’ll blow up like a fucking balloon.”

“Forget it. Your man ever floats, he’ll wash up in the locks. Maybe get pulled down to the river. Means they’ll have company for Johnny boy. Give the fuzz something to think about.”

“Shame about the rug.”

It made less of a splash than either of them expected, swallowed by the dark water. Joblard tossed the gun in after it. There were lights coming on over at the wharf. The six o’clock shift. Time to get a move-on. It was going to be another long day.

— Louis Armand

——————————

Louis Armand is the author of seven collections of poetry and five novels, most recently Breakfast at Midnight (2012) and Canicule (2013), both from Equus (London). His screenplay, Clair Obscur, received honourable mention at the 2009 Alpe Adria Trieste International Film Festival. He is an editor of VLAK magazine and has worked as a subtitles technician at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival. He lives in Prague.