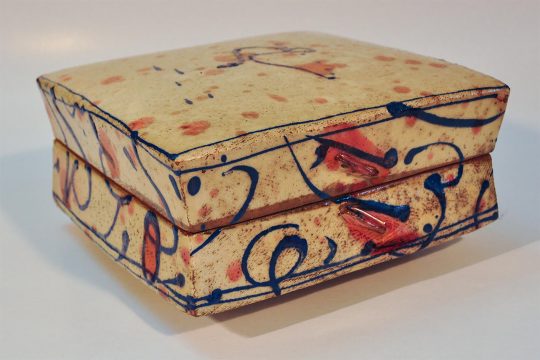

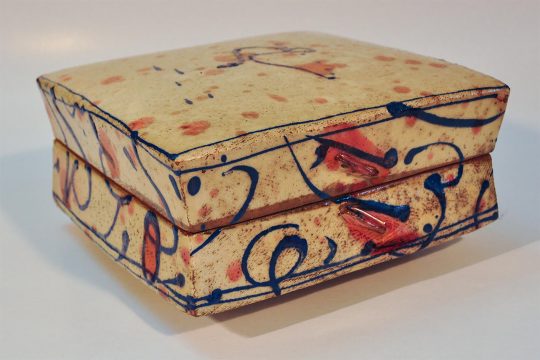

Ceramic box by Michel Pastore

Ceramic box by Michel Pastore

.

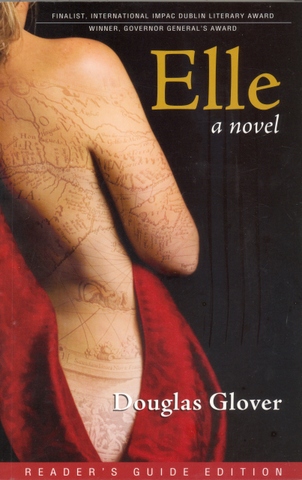

I’m calling this issue the Magic Box, Numéro Cinq‘s magic box issue, mostly because I am so taken by the image above, a ceramic box by the Swiss artist (and fashion designer) Michel Pastore. Pastore, together with his partner Evelyne Porret, are a truly remarkable duo. They live on an oasis outside of Cairo, where they operate their studio and a ceramics school and live in exotic splendor. We have a ton of images from their desert hideaway, stunning objets d’art that are both utilitarian and dreamy, fantastic shapes and colouring. All courtesy of Rikki Ducornet, who knows the couple well.

But to paraphrase the excerpt from Agustín Fernández Mallo’s poem below, inside a box there is always another box, and another, and another…

Even I am astonished and the depth and variety in this issue.

Ceramics artists Michel Pastore & Evelyne Porret

Ceramics artists Michel Pastore & Evelyne Porret

Pastore/Porret house and studio at Fayoum, outside of Cairo

Pastore/Porret house and studio at Fayoum, outside of Cairo

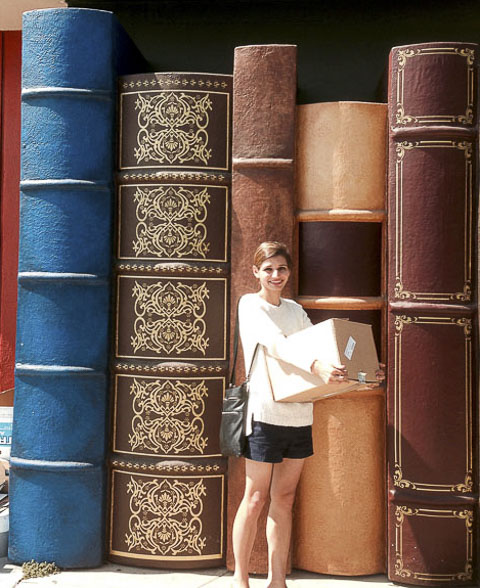

Rikki Ducornet

Rikki Ducornet

And from Rikki herself, an essay on Gnosticism, a dramatized evocation of the beginning of everything and the light.

Attempt to imagine – and the task is futile – an absence, as when the night sky is empty of her moon, of moonshine, of stars, of starlight. Imagine a void in which you are without purchase (there is no place to stand); a night as unfathomable as a pool of ink (there is no pool, no ink) in which the vast firmament has dissolved. There is nothing but absence. (And you, the one who attempts this imagining, are nowhere to be seen.) —Rikki Ducornet

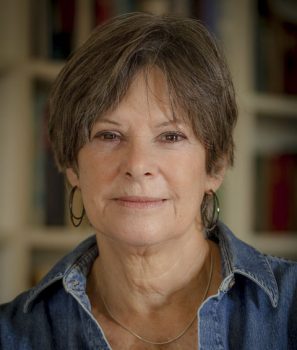

Kelly Cherry

Kelly Cherry

Kelly Cherry sent us a story with a promising title — “Burning the Baby” — of course, we’re publishing it. And more.

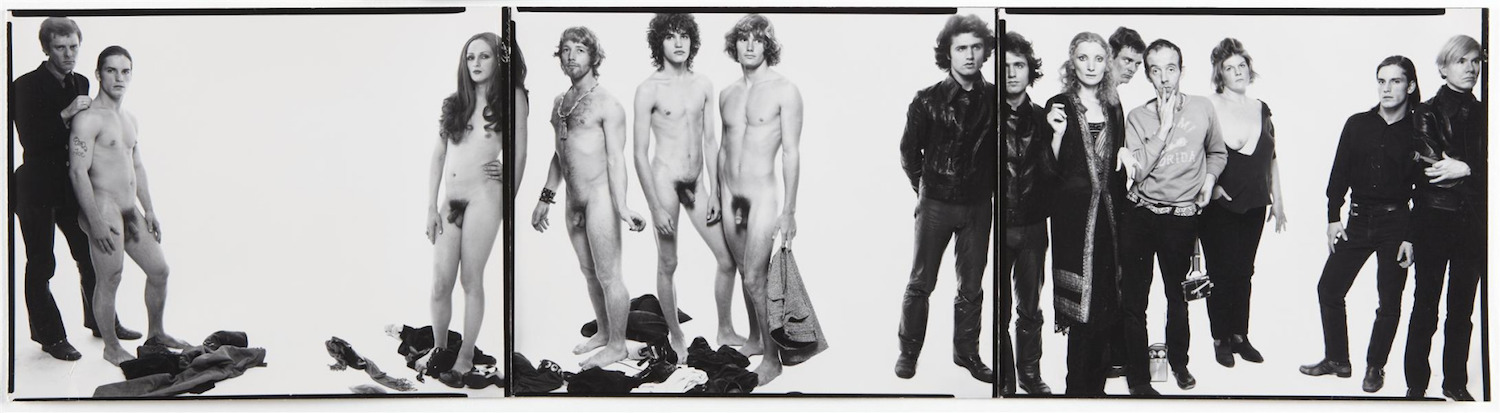

The constant sun enervates. Yes, night still arrives, but one’s skin is burnt so bad that sores appear on arms, legs, and bald heads. People give up on clothes, abandon their garments, for it is too painful to wear them. Everyone gives up. —Kelly Cherry

Carlos Fonseca

Carlos Fonseca

And something truly special, writer/translator Jessica Sequeira interviews Costa Rican/Puerto Rican novelist Carlos Fonseca on his brilliant novel Colonel Lágrimas.

Then again, you can never escape your obsessions. So the novel ended up addressing some of the ideas that intrigued me at the time: the idea of a history as a giant museum, the inability to pass from thought to action, the Borgesian notion of history being reduced to a giant encyclopedia or archive. And then, there is also the story of how – as an adolescent – I wanted to be a mathematician. Perhaps, now that I think about it, the novel was a way of rethinking my past. —Carlos Fonseca

Jessica Sequeira

Jessica Sequeira

Ben Slotky

Ben Slotky

Also inside the box this month, we have new fiction from Ben Slotsky, recommended to us by no less than Curtis White.

Flow, content wording, prioritize critical information, establish a model and keep it. These are precepts, they are tenets. Processes, forms. You are not paying attention. It doesn’t matter. There is too much, a wave, a wash, and it is over, over, and you are gone. —Ben Slotky

James Joyce & Sean Preston

James Joyce & Sean Preston

From East London, we have a short story by Sean Preston, ex-pro-wrestler (among other things).

She had her habits. One of them was buying cheap furniture from places that were so fucking far away, by the time you paid for travel to the ungodly zones of south-west London, you hadn’t really saved much money at all. —Sean Preston

Maura Stanton

Maura Stanton

And we have poems — and then MORE poems — wonderful poetry by Maura Stanton, Susan Elmslie, Fleda Brown (who has a new collection just out), and, from Spain, the legendary Agustín Fernández Mallo translated by Zachary Rockwell Ludington.

Trust me. I’m one who loves all fogs—

misty, yellow, blue, rolling or grey—

I’ll walk your fog down busy thoroughfares

at any hour, clean up its wet messes,

pull it away from streetlamps and hydrants

but let it sniff around in the shrubbery

or blow its light breath against a window.

……………………………………….—Maura Stanton

Agustín Fernández Mallo

Agustín Fernández Mallo

Underneath this skin is another skin,

and under that another, and another, and another,

and thus, as many layers as you like, until n∊N→∞

antecenter of the center which is finite.

That center is the mask.

……………………………………….—Agustín Fernández Mallo

Susan Elmslie

Susan Elmslie

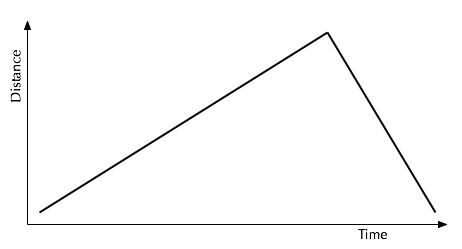

After the chaos there is silence,

a failure of words but not of sound,

which we know travels in waves,

and the speed of which is still the distance

travelled per unit of time.

…………………………………….—Susan Elmslie

Fleda Brown

Fleda Brown

Good, the blatant coffin, the procession,

the undertaker, the taking under.

To turn a body to ash—I can see how

it flies in the face of full-on facing

how slow the earth means to be.

………………………..—Fleda Brown

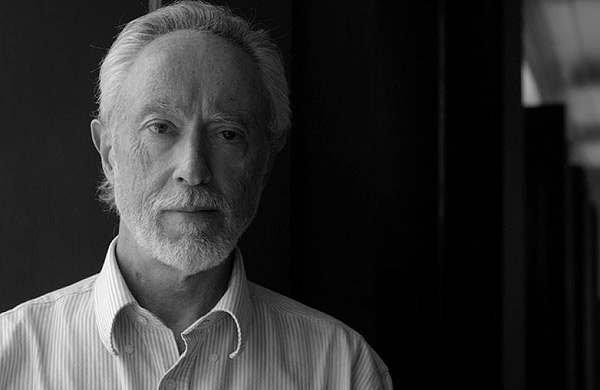

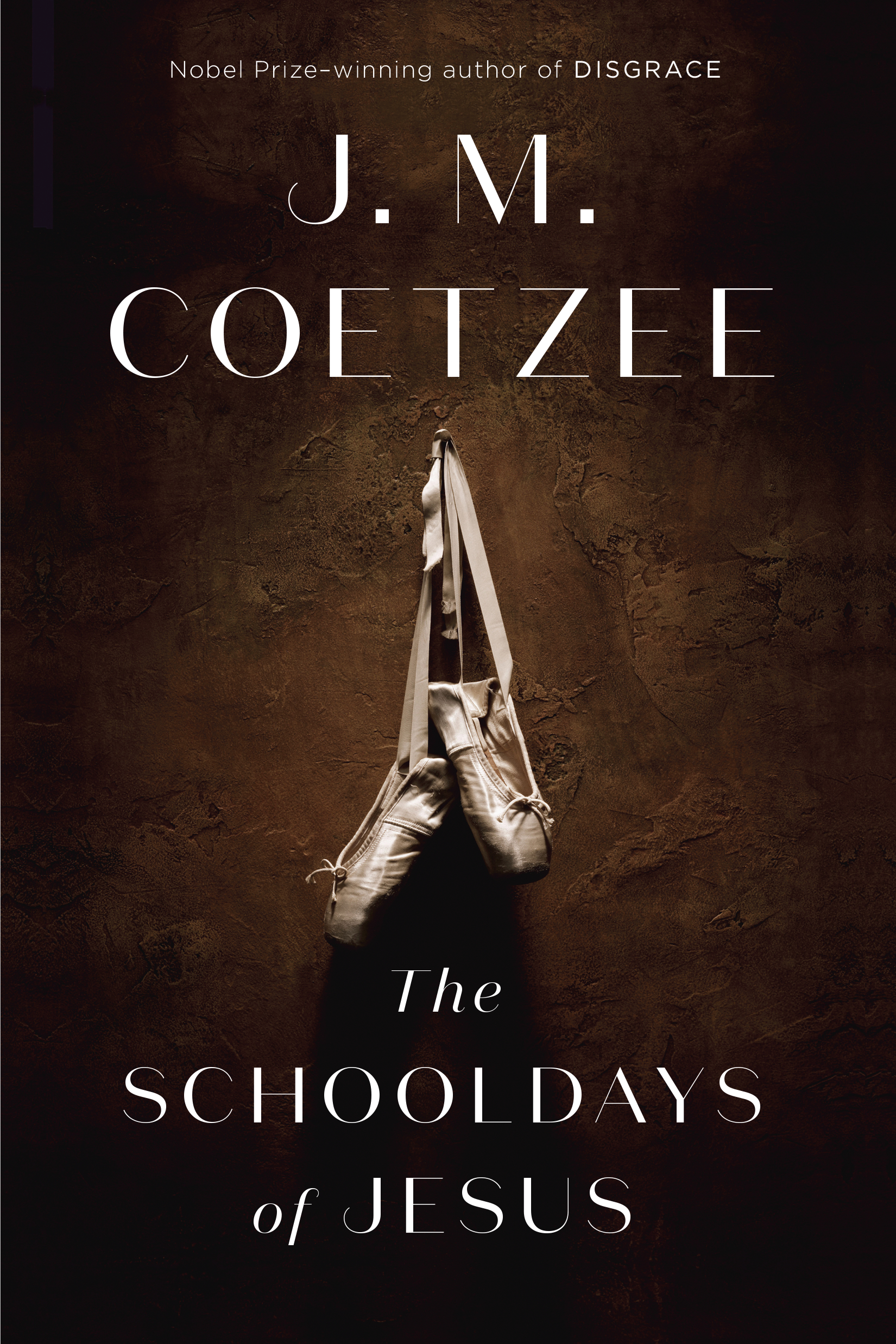

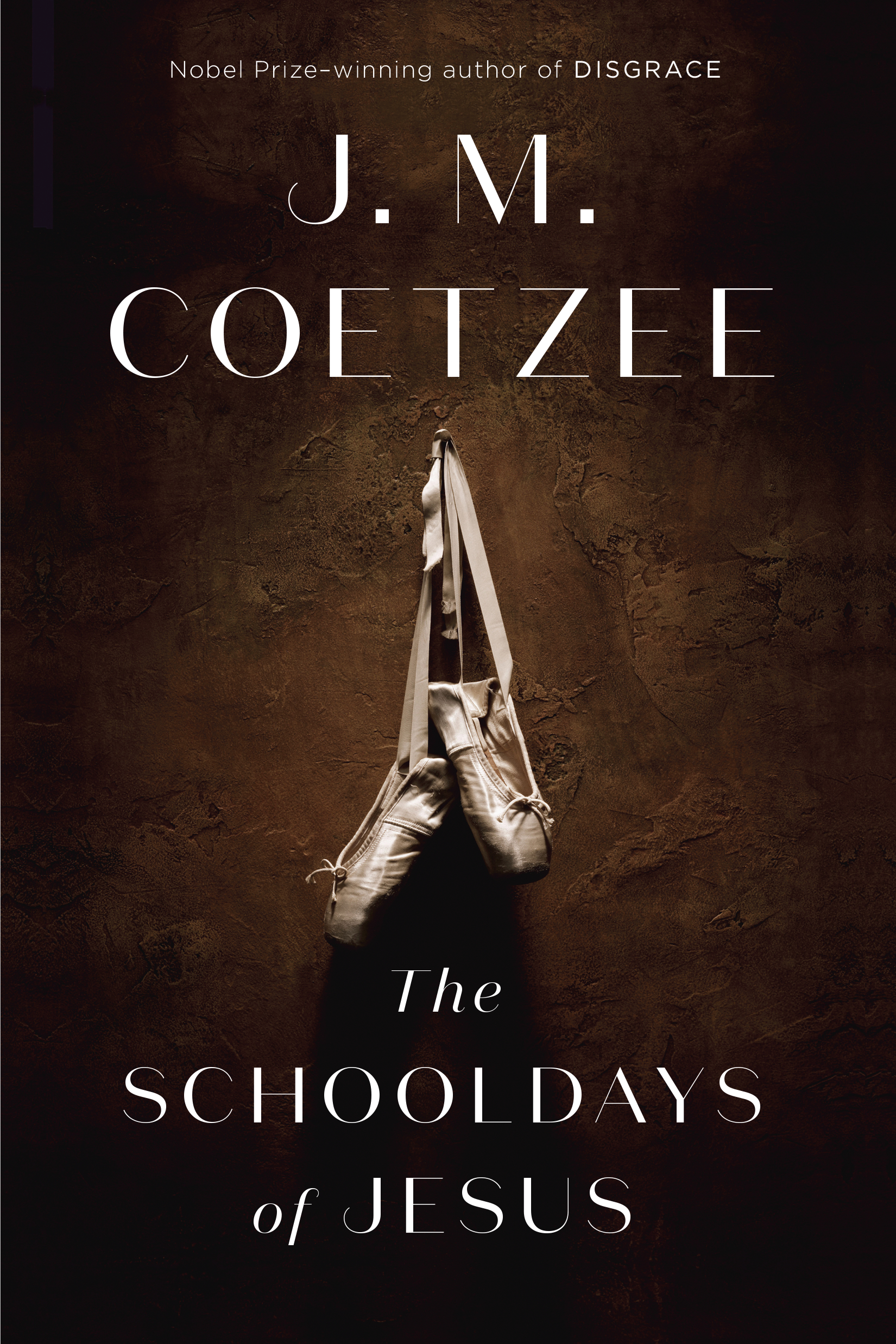

J. M. Coetzee

J. M. Coetzee

Our Book Review Editor, the inimitable Jason DeYoung, reviews the latest from that other inimitable — J. M. Coetzee.

By the way, no one in this novel is clearly named or called Jesus. Only the title teases that one of the characters is—perhaps—the historical Jesus. Perhaps post crucifixion, perhaps not? Perhaps this isn’t the historical Jesus at all—perhaps Coetzee is playing a game on us. Perhaps not. But the reader can’t help looking for parallels. —Jason DeYoung

Anne Hirondelle’s Aperture 14, 16″ x 16″

Anne Hirondelle’s Aperture 14, 16″ x 16″

Anne Hirondelle returns to our pages with a mix of drawings and ceramics. Readers loved her work last time, and she has a new show just opened.

Anne Hirondelle

Anne Hirondelle

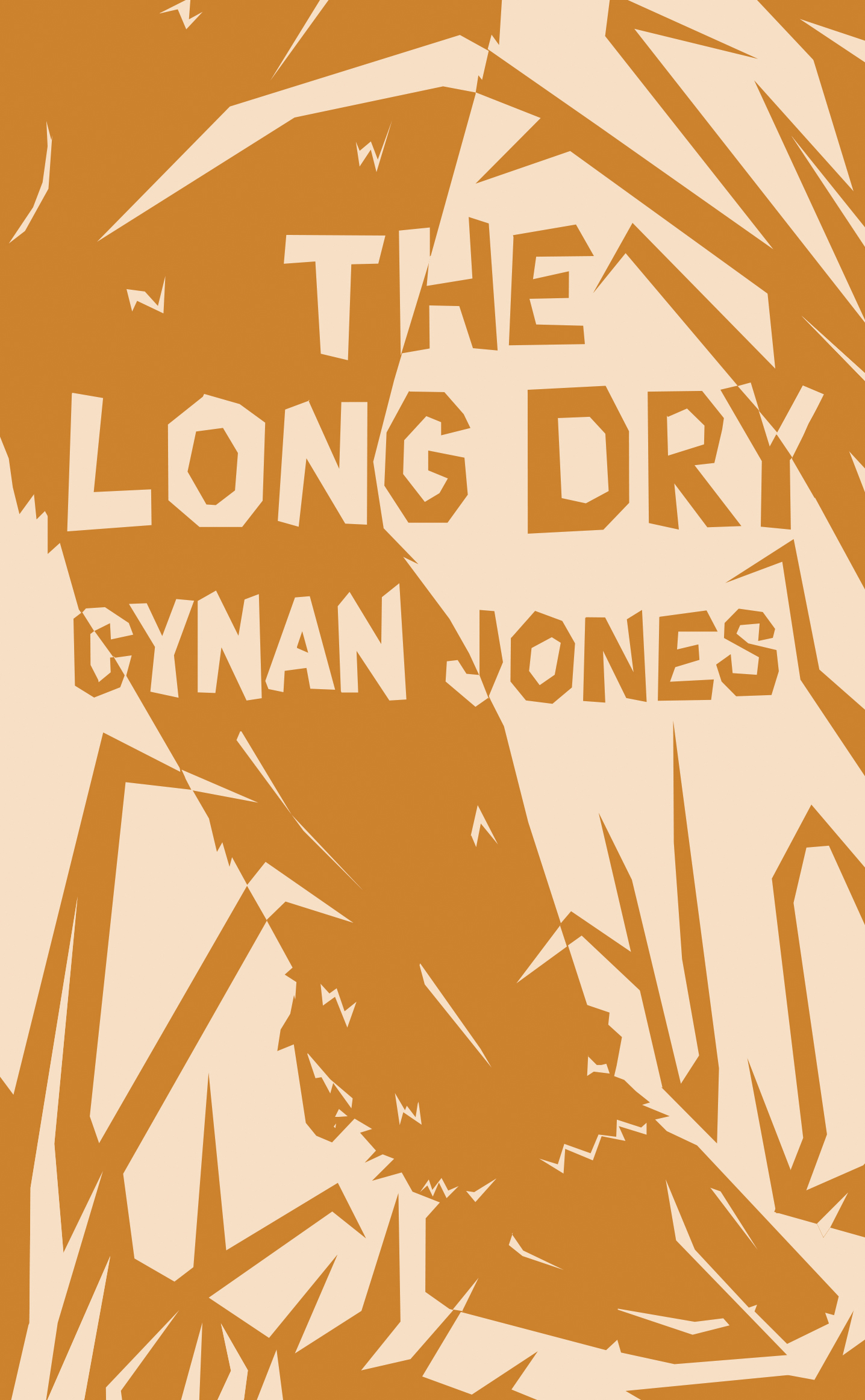

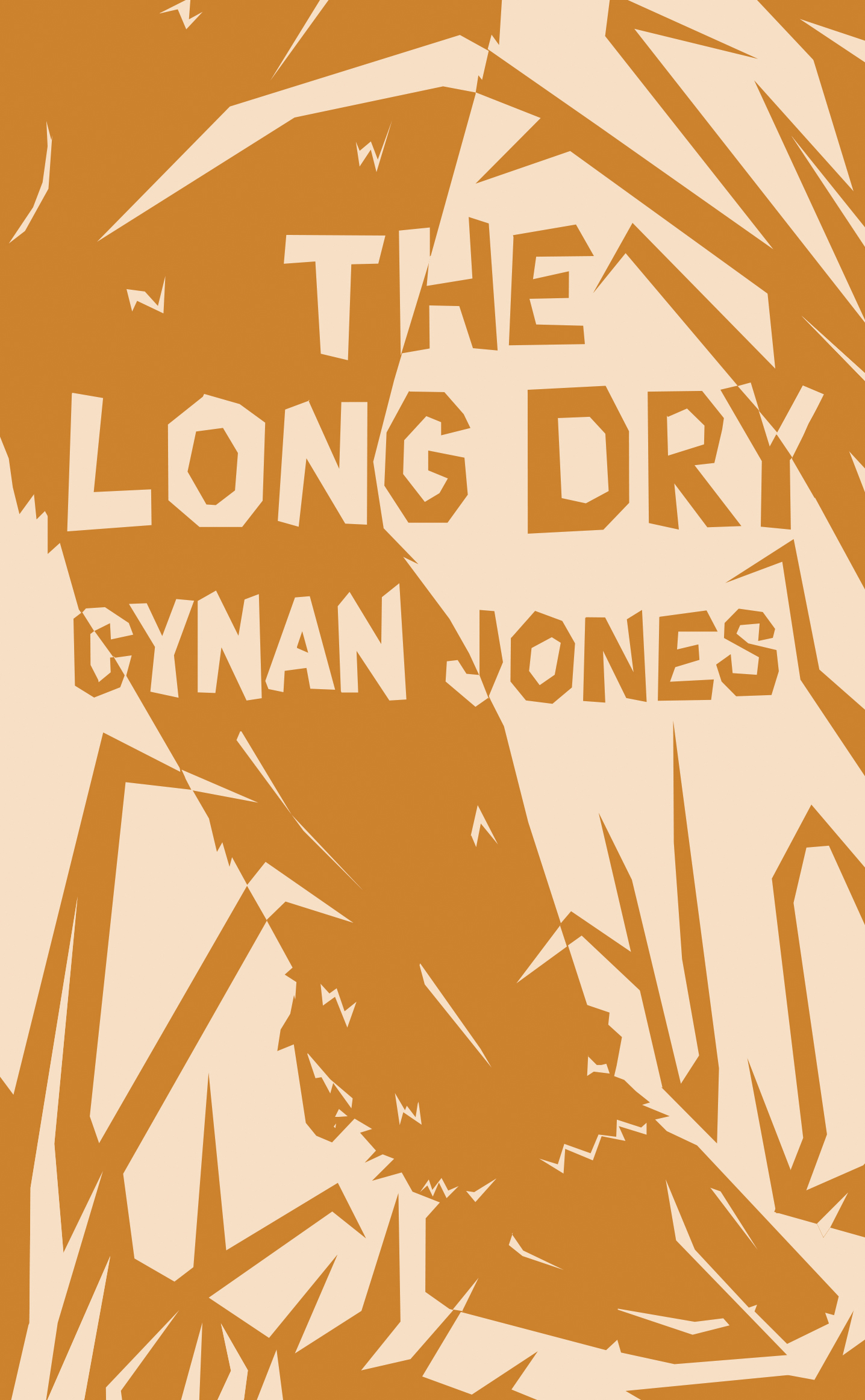

Cynan Jones

Cynan Jones

Mark Sampson reviews Cynan Jones’ “otherwise dark, brooding, brutal and devastating” novella, in which ducks appear.

In The Long Dry, Jones writes very well about ducks, their sex lives, and their feces. In fact, if there were an International Literary Prize for Writing about Ducks, Their Sex Lives, and Their Feces, Jones would easily win it. These passages are moments of levity in an otherwise dark, brooding, brutal and devastating novel –Mark Sampson

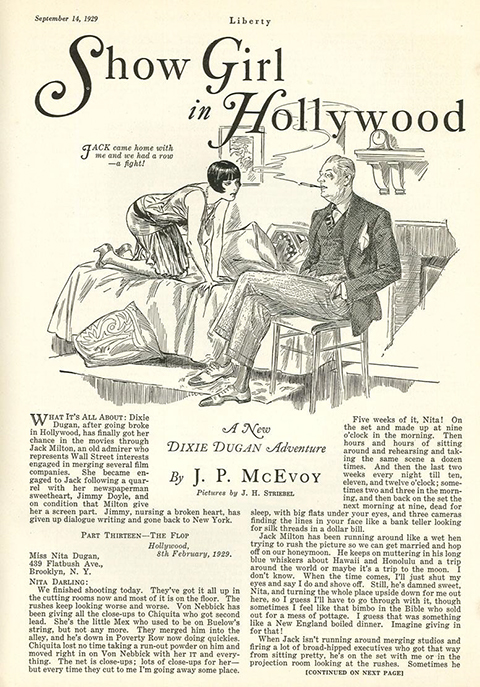

Also we have from Steven Moore, a vastly detailed (lots of images) and fascinating essay on the protean, prolific and once famous “avant-pop” novelist-cartoonist-screenwriter J. P. McEvoy.

But literary historians have overlooked a novelist from the same decade who deployed these same formal innovations largely for comic rather than serious effect, adapting avant-garde techniques for mainstream readers instead of the literati. —Steven Moore

Steven Moore

Steven Moore

Montaigne

Montaigne

Linda Chown is a new voice at the magazine. She’ll be back. But first this lively review of a new anthology of essays by Michel de Montaigne.

Repeatedly, Montaigne thinks of his efforts as flawed, monstrous or distorted. To become his reader, I have had to become a kind of ventriloquist engaged in an act of translation and projection, of time, genre, gender, language and many translations. It was only when I found how uncertain, fearful and tentative he was that I could begin to write of him wholeheartedly. —Linda E. Chown

Linda E. Chown

Linda E. Chown

Yannis Livadas

Yannis Livadas

The Greek poet Yannis Livadas, whose poems have appeared on these pages in the past, returns with an essay on the theory and inspiration behind his experimental work.

What is born is condemned to death and to being absorbed by the newly born. The newly born is more specifically regulated by death. The newly born is the exchange value of death. Life, is the daemon – poetry, is the teaching of the absolute nullity. The irreversible perforation of what has been poetically affirmed by those who are still spendable. —Yannis Livadas

Amanda Bell

Amanda Bell

From Ireland this month, we have a beautiful and evocative Childhood memoir from Amanda Bell.

The boat bay was fringed with hazel scrub and thorn trees, and purple loosestrife and blue scabious grew in the coarse yellow sand. It was a very good place to catch grasshoppers and daddy-long-legs for dapping, and because I was small and moved quietly I was the champion hopper-catcher. —Amanda Bell

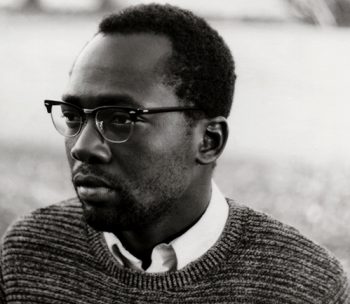

Timothy Ogene – photo by Claire MacKenzie

Timothy Ogene – photo by Claire MacKenzie

The Nigerian poet Timothy Ogene (whose poems have appeared here) has written an essay on the American poet Ruth Lepson (whose poems have appeared here).

In Lepson’s work, thought reveals itself in the choice and structural placement of words and, in other instances, a reluctance to carry an emotion to an expected end. The goal, it seems, is to create a binary that balances overt emotions with critical deliberations. —Timothy Ogene

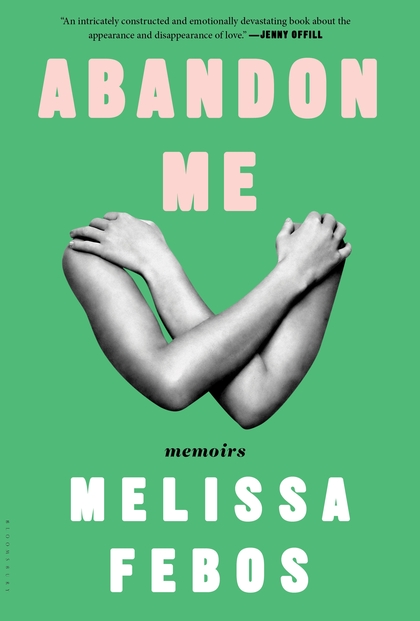

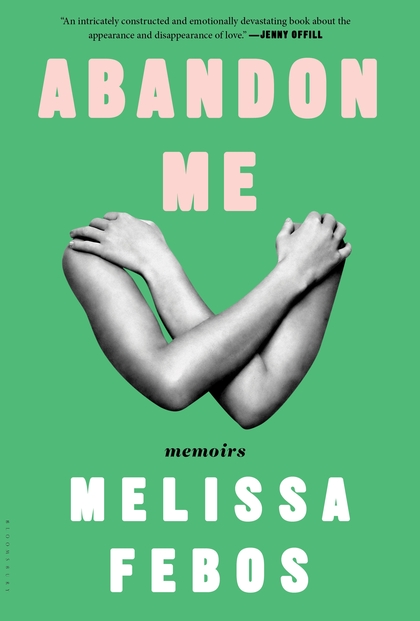

Melissa Febos

Melissa Febos

And our own Carolyn Ogburn pens a rave review of Melissa Febos’ memoir Abandon Me.

I’m told if you score a bullet across its tip with a pocketknife, first lengthwise then across, your shot will penetrate its target cleanly, but ravage the organs inside. I thought of this when reading the blunt, clean prose of Melissa Febos in her new memoir, Abandon Me. —Carolyn Ogburn

But there is MORE!