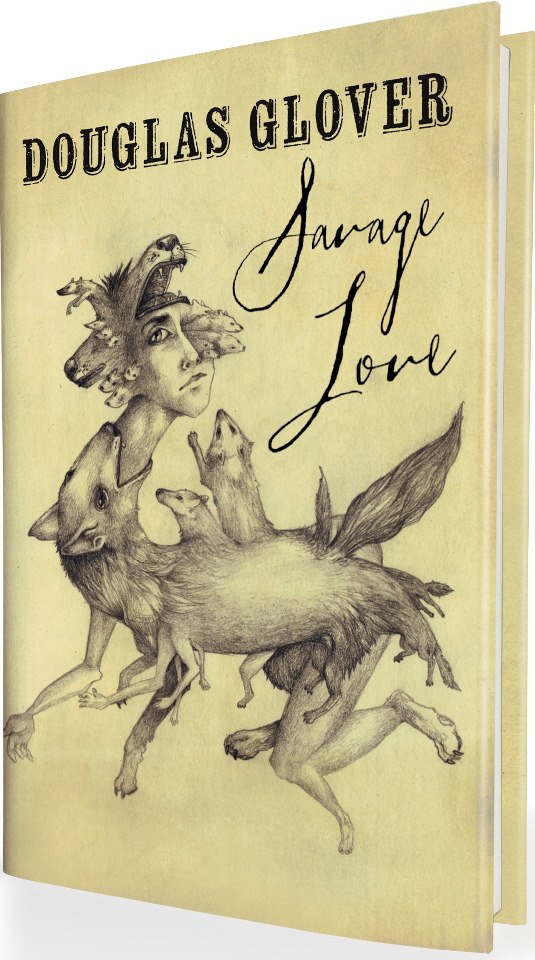

Click on the image for the publisher’s page.

Click on the image for the publisher’s page.

For more about the artist, go here.

Click on the image for the publisher’s page.

Click on the image for the publisher’s page.

For more about the artist, go here.

I’ve read his stories, his diaries, and the novel Cosmos (over and over, essay on that coming eventually); the erotic events are mostly elided in the diaries.

dg

The new book lays out Gombrowicz’s meticulous monthly tabulation of concerns – his erotic ventures as lists of partners’ first names, and his health and lack thereof, are the carnal, corporeal priorities. Finances, travel, meetings, invitations, exchanges of gifts and letters are listed. Code words are pointed out in footnotes: “commisariat” when his influential cousin or embassy contacts got him out of Argentine jails, likely for soliciting sex; “Durant” for the Buenos Aires hospital where he received injections to treat syphilis. In finding a form for his unrelenting self analysis, the new book gives the writer something of a last word on his life.

We published Sharon McCartney’s poem “Deadlift” in the December issue. She just got word that editors Molly Peacock & Sue Goyette have selected that poem for inclusion in the Best Canadian Poetry 2013.

Some of you will recall that Sharon McCartney’s poem “Katahdin,” also published in Numéro Cinq, was included in Best Canadian Poetry 2012.

Go, Sharon!

Reading through Andrew Gallix‘s online opus, I found this fascinating bit on René Girard’s Deceit, Desire and the Novel, book that has endlessly influenced what I write and think. Read Gallix; then read Girard.

dg

Discovering Deceit, Desire and the Novel is like putting on a pair of glasses and seeing the world come into focus. At its heart is an idea so simple, and yet so fundamental, that it seems incredible that no one had articulated it before. Girard’s premise is the Romantic myth of “divine autonomy”, according to which our desires are freely chosen expressions of our individuality. Don Quixote, for instance, aspires to a chivalric lifestyle. Nothing seems more straightforward but, besides the subject (Don Quixote) and object (chivalry), Girard highlights the vital presence of a model he calls the mediator (Amadis of Gaul in this instance). Don Quixote wants to lead the life of a knight errant because he has read the romances of Amadis of Gaul: far from being spontaneous, his desire stems from, and is mediated through, a third party. Metaphysical desire — as opposed to simple needs or appetites — is triangular, not linear. You can always trust a Frenchman to view the world as a ménage à trois.

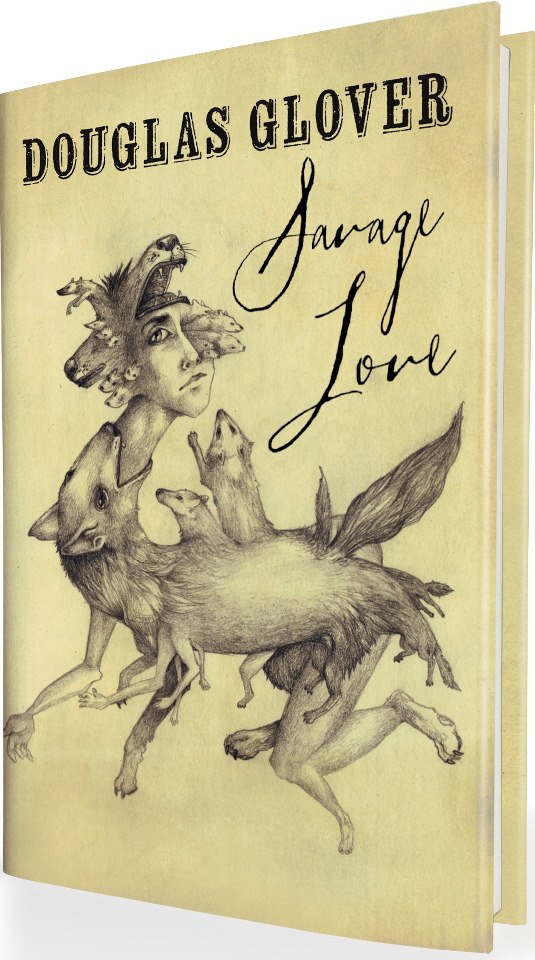

One of those recent trips took me to Canada, where I was one of six artists participating in a couple of mixed-genre events. These were arranged by the wonderful Ontario poet and essayist John B. Lee, whose works are so copious, accomplished and varied that I can’t single out any one, two or three books by his hand to recommend. Google this terrific author and you won’t be disappointed, whichever book may catch your fancy.

Besides John, I sat in with Marty Gervais, another more than noteworthy Canadian poet (and journalist), one whose modesty, both personal and literary, belies a huge soul and deep insight; and with longtime friend Douglas Glover, whose readings of some of his short-shorts (though he practices a number of other fictional and essayistic modes) roused the packed houses, first, in Port Dover, a wonderful and funky Lake Erie fishing town, and then, two hours to the west, in Highgate, where we performed in a beautiful old Methodist church, reclaimed as an arts center.

I must likewise mention the two musician-songwriters who rounded out the bill. Young Michael Schotte is, simply, a guitar virtuoso; check him out too. And our master of ceremonies, Ian Bell, curator of the excellent Port Dover Maritime Museum, is also a fine instrumentalist. Ian is also author of song lyrics that are every bit as “poetic” as anything else I heard on those stages. Look him up– and prepare to be mightily impressed.

via Sydney Lea’s Blog: Don McKay and Canada’s cultural riches.

KK: The speed is the most important thing. Both challenge the concept of form but the speed has a practical element as well for me because I am a perfectionist in my writing, in my way of thinking and I want to be clever and I want to make it into real art, real literature. But I had to fight against that thing in me because I became so critical of my own writing and I needed to get over that, and the only way I could do it was by speeding up because then you don’t have time to be critical at all.

It also allowed me to escape the notion of knowing what to write. If you know what you’re going to write then that’s death for me, then nothing is happening. If I plan something it’s just dead. And almost everything I write is dead in that sense really, but if I speed up then something, all of a sudden, is happening because I can no longer control it.

There’s also something else in there too. When I was nineteen I went to a creative writing course and we were basically taught that if something is bad then you should just take it away, essentially a very minimalistic approach to writing. It took me ten years to overcome that and to understand it’s possible to do the opposite, that if it’s bad you can just add more in because then something else is happening.

It’s the same thing with the length. If you write a hundred pages then it’s all about concentration, it’s all about sentences or language. But if you write 3600 pages the sentences are no longer the important thing, it is something else that is going on that’s difficult to explain.

Fascinating essay linking the Kantian tradition and Borgesian formalism, the meaningful meaninglessness of form.

dg

Both the notion of purposiveness without purpose and the notion of genius irreducible to concept lie behind Borges’ speculations about the wall and the books: Borges is fascinated by the possibility of something that can be “nothing but form,” and by the notion that a formal pattern “hints, but only hints, at significance.” Borges mentions Benedetto Croce and Walter Pater in his essay—and neither figure would exist in recognizable form without Kant. But another figure derived from the German Idealist tradition comes to mind in connection with Borges’ idea of the “imminence of a revelation, which does not happen” as central to aesthetics: Carl Gustav Jung. Jung, in his great essay “On the Relation of Analytic Psychology to Poetry,” argues that the most significant forms of art give us not specific meanings per se, but “a language pregnant with meanings, and images that are true symbols because they are … bridges thrown out towards an unseen shore.” Meaningfulness without meaning, we might say, is the gist of Jung’s theory, here: and it is certainly a theory in accord with Borges’ fascinations.

via Samizdat Blog: The Haunting of Jorge Luis Borges, or: Borges in the Kantian Tradition.

“We have the option of optimism,” writes Darran Anderson in his lovely, wonderful review essay/appreciation of Kevin Jackson’s Constellation of Genius – 1922: Modernism Year One (not yet out in the U.S., pub date September). It’s all well and good to talk about aesthetics and traditions and the history of ideas, but what Anderson nails to a T is the sense of wonder, adventure, rebellion, excitement and optimism of the mo(ve)ment. Anderson himself comes across as a genial, bookish traveler, dragging his wine-stained, scarred books around the world. As time goes on, you learn that books are your best friends and the last refuge of quality in this meretricious world (doesn’t matter that there are a lot of trashy books, too; you don’t have to read them). It’s always a pleasure to discover a fellow reader, as Darran Anderson is.

dg

There are countless amazing creative developments happening right now, instigated by similarly amazing people. Some of them are drunks too, some of them doomed. We’ll not recognise many of them until looking back in years to come, possibly when it is too late, a consequence of Kierkegaard’s “Life is lived forwards but understood backwards.” We are like the fortune-tellers in Dante’s Inferno whose heads are turned backwards so they stumble about unable to see where they are going. We are fumbling blindly into the future, using what has already passed as our guide. We are all Walter Benjamin’s Angelus Novus. Yet these creative people, our own Modernists, do exist if we are perceptive enough to find them and assist them the way Pound, Stein and Cocteau did (not to undervalue their own brilliant contributions). We have the option of optimism. We have the added bonus of more history to ransack than the Modernists had and technology that would have been barely imaginable to them. We can speak to each other, as we are now, immediately and internationally without a single ship, telegram or astral projection having to be utilised.

The reason I love Modernism is that it reminds me of possibilities. If we can find nothing to astonish us, we must make things to astonish. The world is plural and the art that reflects it will never be finished, so long as there’s breath in our lungs. Let the naysayers understand, in terms of possibilities, we have barely begun.

An absolutely wonderful essay on the forgotten and neglected late 19th century author Marcel Schwob by Stephen Sparks who, among other gigs, contributes to the site Writers No One Reads which I have mentioned before, as I have mentioned Stephen Sparks before — a man whose passion for books makes everything he writes tantalizing and exciting. Reading Sparks inevitably sends you off on curious, bookish adventures in a dozen different directions at once.

dg

By condemning Schwob to the category of the myopic scholar tracing obscure references through a series of increasingly arcane books and manuscripts, we risk overshadowing his emotional sensitivity, which is as keen as his erudition and is the mark of an artist who deserves a better fate. This sensitivity manifests itself in his curiosity about the individual, which is apparent in the preface to Imaginary Lives, a book once described, in a quaint (and, to modern ears, damning) romantic manner, as the “lives of some poets, gods, assassins and pirates, and several princesses and gallant ladies.” In a passage lamenting the inadequacies of ancient biographers—“Misers all,” he sighs, “valuing only politics or grammar”—Schwob emphasizes his belief in the necessity of an art that unclassifies rather than classifies, one that cares less for the sweeping generalization than it does in uncovering each individual’s anomalies:

Contrary to history, art describes individuals, desires only the unique… consider a leaf with its intricate nerve system, its color variegated by shade and sun; the imprint of a raindrop; the tiny mark left by an insect; the silver trace of a snail; or the first mortal touch of autumn gold. Search all the forests of the earth for another leaf exactly like it. I defy you to find one.

A female Pileated Woodpecker flew into my front window this afternoon. She was down on the concrete path when I found her, one wing splayed out, one foot curled under at an ugly angle. But she was moving her head. I retrieved my handy turkey baster and got her to drink some water, and then some more. She seemed to get the idea of the baster. Then I folded her wing back straight. And waited. She lurched finally and got her foot underneath correctly, had some more water, and then started to vocalize. Wonderful to hear. You never get close to birds like this. Very satisfying to see her back in the trees. You can see that in the first photographs she looks pretty stunned, eyes half-closed, beak open. Someone should write up the medical use of turkey basters.

dg

I’ve been writing books for decades, teaching writing on and off for less than 20 years. Teaching makes up much less of who I am or how I present myself to myself than writing, being a father, etc. But it does provide me with a measuring stick (what are people thinking and reading these days?) and an occasional locus for thought (how does one explain how a work of literature is built?). One of the things I’ve noticed in my years of teaching is how few people come to the craft with much understanding of the context, the cultural backdrop, the history of ideas that informs works of art now. This is kind of like driving a car while wearing a blindfold. There is a huge difference between writing a sketch of a story or a bit of memoir and creating a work of art out of that sketch, between just getting down the bare facts and writing something beautiful, between anecdote and a short story, novel, essay, memoir. Modernism, as Gabriel Josipovici talks about it in his book What Ever Happened to Modernism? arises out of this distinction, the distinction between bare communication and art, between the naive use of language and the use of language that is aware of its own contradictions, glories and insufficiencies. I have a page on NC, the Necessary Books page, which lists some of the books I have found helpful in informing my own sense of context. And recently I’ve been telling students and the poor, long-suffering writers on the NC masthead, to read Josipovici’s book. No book tells the whole story, spells out the answers; we all have to assemble our own sense of tradition. But the ideal is always to be moving toward a larger and larger awareness of the intellectual furniture of the world. I append here three reviews of Josipovici’s book to whet your appetite. And then, to complicate matters, because matters should always be made more complicated, I add a link to David Winters’s review of Shane Weller’s Modernism and Nihilism.

dg

A long time ago Philip Roth said that there are around 60,000 serious readers in the United States. That is 60,000 who would buy a Philip Roth book, maybe, but realistically there are much fewer serious readers. The kind of readers who sit up late with Ulysses, or who consider Kierkegaard’s Either/Or to be beach reading. What’s more, of these readers I would guess that a significant percentage of them have a go at writing fiction or poetry. Even if they were all lucky enough to be published, a single popular novel would be enough to sap all the media attention away from them (even in the age of the internet, which, by the way, is conspicuously absent as a force in this book. I’m not complaining; it was actually a serene delight to read a new non-fiction book that did not pour on the dreaded “e” prefix remorselessly.) The fault is not with the authors, as such, but with the culture and the criticism surrounding them. It is this that Josipovici wants to change.

And it is a gargantuan task. If contemporary culture has taught us anything it’s that a worldwide web, a few dragging steps towards equality, and a more inclusive attitude in general have almost no impact on public taste. Most people just don’t care enough about the arts to do anything other than lie supine and wait to be entertained, and one wonders if this book can have any traction in a culture that resists elitism so stubbornly. And yet I can’t help but feel that this book is so alive because the world is turned the other way. Even with insurmountable resistance, What Ever Happened to Modernism? is an inspiring, sometimes electrifying, call to arms; a serious book for serious readers.

via The Millions : Getting Serious: Gabriel Josipovici’s What Ever Happened to Modernism?

§

For Josipovici modernism is a response in art (all art, music and painting too for example, not just literature) to the “disenchantment of the world”. That disenchantment is the loss of the Medieval sense of the numinous as being part of everyday life. In short, the Medieval vision of a world filled with purpose and divine meaning gave way to what would ultimately become the Enlightenment with its vision of a secular world governed by reason and natural laws (yes, I did just gloss over about 400 years there).

This is absolutely critical to everything that follows. The death of enchantment does not mean that people were happy in the middle ages but disillusioned thereafter. It is not a personal loss of enchantment. The point is that the European concept of the world changed from it being a place in which the natural and supernatural were different facets of the same reality to a world in which the natural and the supernatural were firmly separated (and in which the supernatural could therefore potentially be discarded entirely).

With the death of enchantment comes the death of meaning. Before the disenchantment of the world it is possible to speak with authority, because the world has meaning from which authority can be derived. After that disenchantment there is no longer such an authority. The only authority that exists is that which we assert.

via The death of enchantment | Pechorin’s Journal.

§

The Modernist project has been around for far longer than you might think: from Euripides, looked at one way; or from Rabelais, looked at another; certainly since Cervantes. “Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember …” is how Don Quixote begins, and it is as if the rest of the book is itself a huge piss-take of the very idea of narrative, a healthy scorn for plodding literalism. When Duchamp – he of the urinal in the art gallery – was asked in 1922 for his views on photography, he replied thus: “Dear Stieglitz, Even a few words I don’t feel like writing. You know exactly how I feel about photography. I would like to see it make people despise painting until something else will make photography unbearable. There we are.” Josipovici notes the “very Beckettian style” of this (pre-Beckett though it may be); and it reminds us that the Modernist avant garde is by no means without a sense of humour.

via What Ever Happened to Modernism? by Gabriel Josipovici – review | Books | The Guardian.

§

To consider the concept of nihilism, Simon Critchley once remarked 1, is to take up the trail of ‘Ariadne’s thread’, a theoretical route through the labyrinth of history. For Critchley, the story of nihilism is the story of what it means to be modern, and to read the philology of nihilism, of the nihil, is to look through a lens at modernity’s underside. Shane Weller’s survey of the web of relations between Modernism and Nihilism proceeds from the same supposition. His book unpicks the thread where it’s at its most knotted, in the high modernist literatures of the early twentieth century. For Weller, what’s at work in the works of the modernists – from Tzara to Kafka to Cioran – is a discursive puzzle for which ‘nihilism’ would seem to be the key, the master term that could unlock and make sense of the modern. Yet the thrust of his thesis is the fact that it fails to do so; the way that whatever it touches is rendered resistant to interpretation. So, on the one hand, thought and talk about ‘nihilism’ is ubiquitous across modern culture: wherever the modernist moment is, nihilism sits alongside (or inside) it. On the other, modernism proves unable to reduce nihilism to its propaedeutic, its explanatory toolkit. Rather, nihilism is what haunts modernism, as its ghost or double, a tense co-presence forever unsettling its meanings.

via Modernism and Nihilism by Shane Weller « Book Review « ReadySteadyBook – for literature….

Here’s an interview I did with the Irish novelist John Banville in 1995 after the publication of his novel Athena. Below are two of my reviews of Banville novels. At the beginning and the end, Banville (politely) disagrees with what I say about him (also in the middle somewhere). His disagreement seems a bit disingenuous. I still read his complex and intellectually rich books and shake my head at the idea that he is just describing the world he sees when he looks out his window. In any case the main thing in an interview is to get the subject to say something interesting. It’s a treat to hear Banville’s voice as he discusses his own work; there is a stretch when he begins talking about the beauty and tenderness of the world that is just gorgeous.

Once again, I retrieved this from a box of tapes, clumsily recorded and even more clumsily transferred to an mp3 file. There are a couple of skips near the beginning for which I apologize.

dg

Banville Part 1

Banville Part 2

Banville Part 3

On John Banville’s Ghosts

John Banville is an Irishman with the gift of blarney, an author who writes gloriously impossible novels that seem to evanesce like peat smoke or mist out of the bogs of that strange island, phantasmagoric novels that swirl and race and swallow their own tails or dance between morbid melancholy and golden, baseless hope.

He is best known in America for two historical novels, Doctor Copernicus and Kepler, about the Renaissance astronomers who turned the known world upside down. But lately Banville has returned to the Irish setting of his earlier books (Birchwood, Long Lankin), a fantastically sterile, degenerate place of decaying aristocracy, mythically dysfunctional families, murder, incest, drunkenness and mega-alienation.

In Banville’s last novel, The Book of Evidence (1989), Freddie Montgomery, a failed scientist, impecunious husband, drunkard, liar and all-round weasel, abandons his wife and child in Spain and returns to Ireland to try to raise money by selling his late father’s third-rate art collection. Unfortunately, Freddie’s eccentric and possibly lesbian mother has already sold the paintings to a wealthy dealer living on a nearby estate. While stealing one of the pictures back, Freddie murders the maid (one of the most pathetic, grotesque and revoltingly detailed murders in literature-a joy to read) and ends up serving a life sentence.

In Ghosts, Freddie resurfaces 10 years later (a life sentence in Ireland) as the novel’s unnamed narrator, ex-con, amanuensis and ghost writer to a retired art history professor living on a sparsely inhabited island with his books and a galumphing servant-keeper named Licht (sort of a cracked Prospero with his Caliban-plenty of Shakespeare allusions here).

The professor is supposed to be an expert on Vaublin, a minor Parisian painter who apparently went mad or was haunted by a mysterious imitator in the months leading up to his death. In fact, the professor isn’t an expert and has fraudulently authenticated as Vaublin’s a little masterpiece called “Le monde d’or” (“The Golden Word”), which made up part of the collection Freddie pillaged in The Book of Evidence. He is happy to hand over the work of writing Vaublin’s biography to the maid-murdering narrator.

All this is background, and most of it comes clear late in the book. The connections between Ghosts and The Book of Evidence are pleasing to note without being necessary to the reading of either work. I mention them only because they are about all that can be said with certainty about what happens in Ghosts.

Ghosts actually begins with a shipwreck (shades of The Tempest again). A small band of tourists-two women, an old man, a Mephistophelean character named Felix and three children-is unceremoniously dumped on the island by a drunken ferry captain who runs up on a sandbank at low tide. The tourists feel a mixture of strangeness and familiarity as they clamber up the dunes to the professor’s house.

These tourists bear a striking resemblance to the figures in Vaublin’s painting of the Golden World. In fact, they may be the people in the painting come to life or they may be real people who have found themselves in a painting (or a novel). And, of course, it may be a fake painting or an authentic painting painted by a fake Vaublin.

Suddenly, Banville’s little book drops down a rabbit hole of complexity, with the text oscillating between what you might expect from a normal novel in terms of character and plot and a bizarre aesthetic universe governed by the literary laws of recurring imagery, parallel structure, doubles and literary allusion.

Nothing much happens in Ghosts, and at the same time a great deal happens. The old man in the Panama hat, for example, becomes confused, then begins to obsess, trying to remember the name of that golden “thing they keep the host in to show it at Benediction.” He wanders off along the dunes, falls down in a faint, then returns to the house even more confused.

The old man’s obscure drive to remember is less an aspect of characterization than the strange feeling a real person might have if his brain were being written into by a conniving novelist named John Banville. The missing word is less important than the fact that it is missing and that it is golden and hence stands for the old man’s dreamy awareness that he has stumbled into an alternate, ghostly universe called the Golden World.

After a series of more or less similarly inconsequential events, the little group of tourists gets back into the ferry, which refloats with the tide and disappears. All except for Flora, a vulnerable, rather pretty nanny who has been taken advantage of by the nefarious Felix (sometimes referred to as Freddie’s double). Flora remains in the house to save herself from these unwanted attentions, and briefly it seems as if Ghosts might flower into a romantic entanglement between Freddie and Flora. But then, Flora, too, drifts away.

“Such stillness; though the scene moves there is no movement,” says Freddie, describing Vaublin’s painting “Le monde d’or” (and by extension the novel itself). “What does it mean, what are they doing, these enigmatic figures frozen forever on the point of departure, what is the atmosphere of portentousness without apparent portent? There is no meaning, of course, only a profound and inexplicable significance.”

This mysterious nimbus of significance is the central marvel of Banville’s novel. His characters seem to do nothing but are suffused with a mixture of valor and sadness, a steadfastness in the face of a fate they know they cannot know. And his text glows with a gritty eroticism—remarkable, considering there is no explicit sex in the book. On every page there is just the ghostly shadow of something that never appears and is never named.

This is unsettling stuff for anyone who likes a conventional story. But it should not be dismissed as self-conscious game-playing or decadent estheticism. The conventional novel relies on a certain set of technical devices (plot, character, setting and theme) to produce a fictional world that is a simplified, stereotyped and rationalized version of our own—a world where motives drive people ineluctably into action, where cause achieves effect.

Banville isn’t trying to write this semblance of reality. Rather, he is rocketing his readers into a kind of hyper-reality, a world at the outer limits of human sensibility, a world whose complexity is not reduced by the everyday filters of common sense and the pressing need to get groceries or feed the cat, a world that begins suddenly to seem more like a dream or a poem than what we normally call life.

In this world we are constantly reminded of the brevity of existence, how we always seem to have just arrived while on the point of departure. We are bemused and battened by messages the provenance of which we are only dimly aware. We push along in our daily heroics without any real sense of purpose, with only the feeling perhaps that there should be a purpose, always bewildered by the feeling of being other than what we seem to be.

Ghosts is a strange and beautiful novel about art and the wistful inconsequentiality of being, a little paean to the human heart as it mutters its defiance into the puzzling void.

—Douglas Glover, Chicago Tribune December 12 1993

b

On John Banville’s Athena

John Banville is an author singularly unafraid of the stigma of hyperbole and baroque excess. His novels are littered with incestuous, decaying families, waifish women inviting the whip or the hammer, and drunken, ineffectual male orphans (real or figurative) who move through an fog of decadence, drift and dread worthy of the great Gothic masters.

Known best in America for his historical novels Kepler and Dr. Copernicus, Banville has lately been mining a vein of contemporary Irish grotesquerie centered on a serial character called Freddie Montgomery. In The Book of Evidence (1989), Freddie, drinking too much and down on his luck, tried to steal a painting from a squire’s country house and ended by murdering the maid with a hammer. In Ghosts (1993), free after serving 10 years in prison (a life sentence in Ireland), Freddie turned up on a sparsely populated island where he had been hired as secretary to an aging professor whose specialty was a little known Parisian painter named Vaublin.

If there can be said to be a conventional plot in Ghosts, it turned on Freddie’s abortive love affair with a young woman dropped ashore by a drunken ferryboat captain. This woman and her shipmates bore a striking resemblance to figures in a Vaublin painting called “The Golden World”—part of the collection Freddie pillaged in The Book of Evidence and probably a fake.

In Banville’s new novel, Athena, Freddie’s back, this time in Dublin under the assumed name Morrow, hired by a man called Morden (who works on a street called Rue) to authenticate a cache of 17th century paintings on classical themes. In contrast to Ghosts, Athena is knee-deep in conventional plot elements. There is a cockamamie art fraud plot—something out of The Rockford Files—with a cop called Hackett and a sinister transvestite gangster called Da. There is a plot of sexual obsession and sadomasochistic love between Freddie/Morrow and a girl called A. And there is an astringently tender subplot involving Morrow’s elderly Aunt Corky (not a blood aunt; the connection is vague), who moves into his dingy flat to die. In the background lurks a mysterious serial killer who drains his victims’ blood.

For much of the novel the cracked love story between Morrow and A., a young woman with preternaturally white skin and bruised lips, takes center stage. From the outset the bumbling, chronically depressed Morrow (not since The Ginger Man have we met a character so engagingly and self-destructively melancholy) is besotted and yet knows that she will leave. His breathless, goggle-eyed account (reminiscent of Humbert Humbert’s in Lolita) of their wanton trajectory, from innocent abandon, to voyeurism, to a menage a trois in a seedy brothel, to spanking and whipping and complicit infidelity, is a droll parody of Victorian pornography—melodramatic, perfervid and decidedly unsexy as the situations become more bizarre and mechanical.

Though Freddie/Morrow has taken pains to conceal his identity, everyone else in the novel seems to know exactly who Morrow is—from the criminals who hire him to authenticate their paintings, to the investigating detective, to A. herself, who shocks Morrow one day by asking him to strike her the way he struck that unfortunate maid in The Book of Evidence. Even Aunt Corky hints that she may not be his aunt but his mother. At every turn, an atmosphere of mystery, unreality and downright fraud dogs his steps, so that, though Morrow is telling the story, he seems more and more like a character in someone else’s book, a cog in someone else’s plot.

And interspersed throughout Athena there are catalog descriptions of the paintings entrusted to Morrow, paintings on classical themes of violence, rape and transformation that bear, on the face of it, a strong resemblance to the events of the book (just as in Ghosts the characters seem to have walked out of the Vaublin painting).

So Athena becomes a kind of echo chamber of comic despair in which everything seems fated or written by another hand, where gods toy with humans and turn them into beasts, where a miasma of solipsism hangs in a world of dream, and mysterious lost children, doubles and putative parents hover just out of focus. When A. disappears near the end of the novel, she leaves a note: “Must go. Sorry. Write to me.” But there is no signature and no address, and Morrow is left with only the presence of her loss, a pneumatic void into which he writes his words.

All this is peculiar stuff—heady, hilarious, hyperbolic and strange. Banville’s literary ancestors are writers like Poe, Beckett and Nabokov. His novels are little wars between a repressive, fusty, petty bourgeois sensibility (Irish, Victorian and Modern, with a capital M) and the dark, bubbling, drunken, violent, godlike forces of sex and madness that lurk beneath the surface of life and language.

On the strength of his novels, Banville is not so much a postmodern writer as a pre-modernist, and his critique of modernity rests on a romantic, Arcadian vision of our pre-Renaissance past. Part-way through Athena, Morrow explains how the invention of perspective in painting destroyed the blissful, circular forgetfulness of the past, “spawning upon the world the chimeras of progress and the perfectability of man and all the rest of it. Illusion followed rapidly by delusion: that, in nutshell, is the history of our culture. Oh, a bad day’s work!”

From this vision, everything else follows: Morrow’s confusion, the novel’s atmosphere of fog and drift result from the application of narrowly rigid concepts of self and reality to a world that is ever and always mysteriously other. Stripped clean of contemporary talk show anodynes and psychobabble bromides, the world of Athena is finally hyper-real—one in which in which loneliness, loss and despair throb at the very center of being, and poetry, once again, is possible.

—Douglas Glover, Chicago Tribune July 9 1995

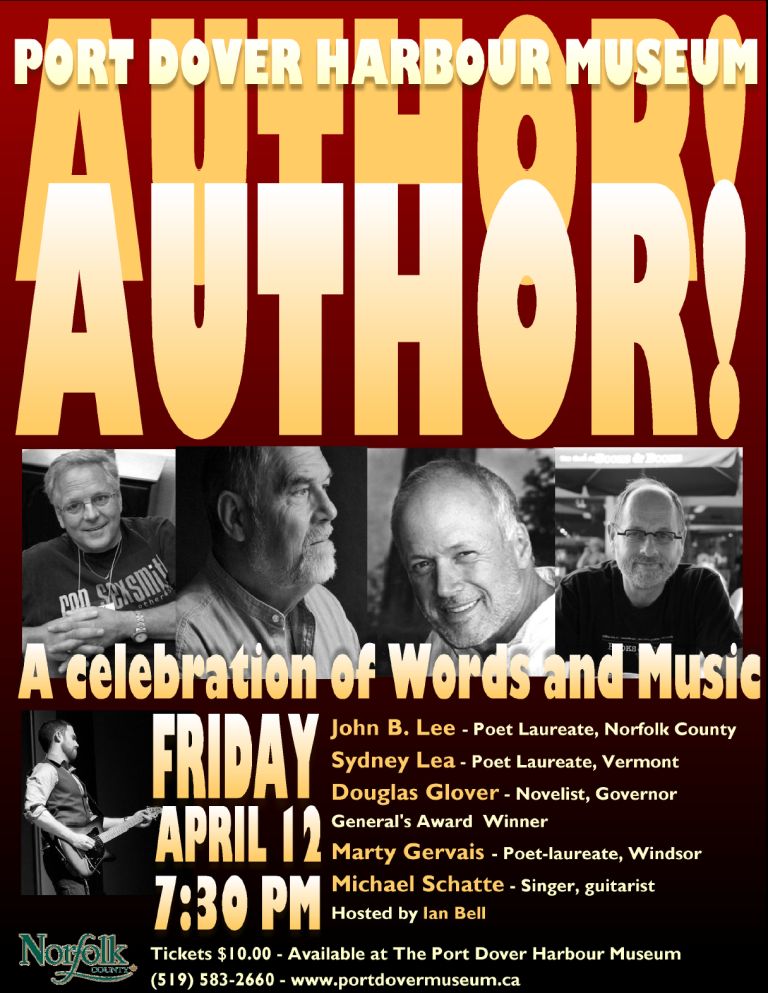

Back from epic, marathon reading and interview trip to Ontario. Arrived in an ice storm. Gorgeous reading events hosted by Ian Bell (his father was my Grade 11 history teacher) and John B. Lee (multiple publications on NC). NC Contributing Editor Sydney Lea was there and I managed to get a photo of him looking like God at the reading in Highgate. Also my very first book publisher, Marty Gervais. The mix of music (Ian Bell and the amazing Michael Schatte) and literary reading was surprisingly entertaining. People paid money to come. Doing two events back to back with a long car ride in between (with stops to visit memorials for famous forgotten Canadian poets and to cast an eye on John B. Lee’s ancestral farm) made me feel like I was on tour with a troupe of actors.

Sunday, I had brunch with the Jernigans, Kim who used to edit The New Quarterly, and Amanda, the poet, and her husband, the photographer John Haney (both Amanda and John have appeared on NC). This was all the more remarkable since they had not had electricity since Thursday (the ice storm). Then I drove to Waterloo to see Jonah and also Dwight and Kathy Storring (Dwight published a play on NC; their son Nathan has an essay here).

Do you get the impression that there are secret NC cells planted all over (you know, mostly so I can travel without paying for food)?

The photo below was taken by Zach Melnick during the War of 1812 documentary interview he did with me on Thursday in the farmhouse living room.

dg

DG being interviewed at the farm, photo by Zach Melnick

Sydney Lea reading in Highgate, Saturday evening

Michael Schatte compilation, on tour with us he performed solo

Possum I found in a den by the pond at the back of the farm

You can hear the dog whimpering next to me. Notice the feet. I once raised a young opossum, called Snuffy, at first I kept him in a fleece-lined leather glove (approximating a mother’s pouch, I thought). My friend Bruce Hiscock did a drawing which hangs in the house. When he seemed big enough, we let Snuffy go in the woods. My great-grandfather was an amateur poet who called himself “Possum” and kept a stuffed opossum in his store. I published an essay about him in The New Quarterly a couple of years ago. More information than you need, right?

First flowers, Coltsfoot

My father once planted a small field with Scotch pine to sell as Christmas trees. As he once observed, they kind of got away from him.

Daffodils in the woods. There are patches all through the woods, planted by DG’s mother.

The farm buildings from the east.

Dog

Dog investigating possum den

Coltsfoot

Geese by the pond

Laneway. To the right, a spruce windbreak. To the left, a field of oak and white pine planted over 15 years ago for eventual harvest.

Last week, for the first time, NC had over 10,000 views.

Last week Jennica Harper’s Sally Draper Poems, published in March, went viral. They were even quoted in Slate Magazine.

This week so far Jason Lucarelli’s essay on Gordon Lish, published in February, was cited in 3AM Magazine in the UK and Mary Stein’s review of Kjersti Skomsvold’s novel The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, published in March, 2012, was linked in the UK Guardian books section. Skomsvold made the list of finalists for the prestigious IMPAC Award; apparently we were one of the few, if not the only magazine to recognize what a brilliant novel she had written.

It’s time to take a moment and reflect with some pride on the international notice we’ve managed to achieve. We are publishing intelligent, original, cutting edge work at NC, and, though we sometimes seem to be labouring in obscurity, we are beginning to be part of a larger conversation.

dg

Okay, now this is interesting yet mysterious. NC has a page, apparently, at the Utne Reader Altwire site. We’ve been picked by the editors as an “influencer” and they aggregate our Twitter feeds. Being called an “influencer” is strangely daunting but pleasant. We are in the “mainstream radar” and “hand picked to follow” — music to our ears. On the the other hand, we have a “mojo” rating of 14 (out of a thousand) — time to bring the whip to the masthead.

dg

Click here for the NC “raw feed” as they call it.

Some explanation gleaned from elsewhere on the site.

About Utne AltWire

AltWire is an aggregator of new ideas and perspectives that allows users to track what other people are reading. The software follows hundreds of groups and individuals picked by Utne editors, and records the links they tweet from a variety of sources. So, when the National Resources Defense Council tweets a story about Obama’s environmental policy from OnEarth Magazine, it pops up here. Fully searchable and updated constantly, AltWire is a powerful tool to see what’s happening below the mainstream radar right now.

What are those Influencers toward the top of the page?

These are people and groups that Utne editors have hand picked to follow on Twitter. Many of them, like Tom Philpott and Jay Rosen, are flesh-and-blood reporters and academics. Others, like Grist Magazine and NASA, are publications and agencies that sometimes tweet stories before they have a chance to reach headlines (we assume there’s a flesh-and-blood person behind NASA’s Twitter feed, but you never know). When one of our Influencers tweets about a new study or news article, you can see it here.

Jennica Harper and her Sally Draper Poems, published on Numéro Cinq in March, have gone viral — over 2700 views in the last three days. Now she’s being quoted in Slate Magazine.

dg

I leave you with this stanza from a poem by Jennica Harper, part of a cycle of poems written in the voice of Sally Draper:

But today I’ll wear red.

The red of a cherry

on a sword in a virgin

cocktail I’ll have to sip

through a straw.

via Mad Men Season 6 preview: Let the saturation coverage begin. – Slate Magazine.

via Michael Filgate @ The Paris Review

via Michael Filgate @ The Paris Review

“The Library of Unborrowed Books” is an art installation by Meriç Algün Ringborg at Art in General in New York, a wall of library stacks filled with, yes, unborrowed library books, something to meditate upon, absence, silence, vanity, desire and text.

Here is an excerpt of an interview with the artist.

dg

“The Library of Unborrowed Books bases itself on the concept of the library as an institution manifesting language and knowledge, of the passing of awareness and the openness to all types of people and literature. This work, however, comprises books from a selected library that have never been borrowed. The framework in this instance hints at what has been disregarded, knowledge essentially unconsumed, and puts on display what has eluded us.

Why these books aren’t ‘chosen,’ why they are overlooked, will never be clear but whatever each book contains, en masse they become representative of the gaps and cracks of history, or the cataloging of the world and the ambivalent relationship between absence and presence. In this library their existence is validated simply by being borrowed, underlining their being as well as their content and form by putting them on display in an autonomous library dedicated to the books yet to have been revealed.”

See more images of the work @ Art in General.

Donald Barthelme’s writing is often regarded as part of the postmodernism movement in fiction alongside Pynchon, Coover and Gass, but I think it is really hard to nail Barthelme to an era or a movement. Surely, he is doing an important commentary on the way we interact with a literary work. His whole writing style is a commentary on how to read. I don’t think we should relegate or constrain him to postmodernism whatever that is. Rather we ought to notice that his writing echoes Laurence Stern and Cervantes along with Joyce. He is not writing toward a new genre. Barthelme is offering an alternative way of reading. And more than that he is demonstrating the changing nature of reading itself—how it makes the literary object other and absurd. Barthelme tells us: we ought not to allow Heidegger to tell us what nothing is, or allow Kierkegaard’s guilt trips to keep us down. We ought to use these philosophers as we read them, as we use our readers while they read us.

This interview with Paris Review is particularly revealing about the way Barthelme sees fiction and writing. One of my favorite aspects is the conversation he is having with phenomenology and questions of presence as a way of encountering literary objects. In a terrific essay called “After Joyce,” Barthelme proclaims: “The reader reconstitutes the work by his active participation, by approaching the object, tapping it, shaking it, holding it to his ear and roaring into it.”

Click here to read: The Paris Review Interview with Donald Barthelme

— Jacob Glover

I have always been a big proponent of following your heart and doing exactly what you want to do. It sounds so simple, right? But there are people who spend years—decades, even—trying to find a true sense of purpose for themselves. My advice? Just find the thing you enjoy doing more than anything else, your one true passion, and do it for the rest of your life on nights and weekends when you’re exhausted and cranky and just want to go to bed.

It could be anything—music, writing, drawing, acting, teaching—it really doesn’t matter. All that matters is that once you know what you want to do, you dive in a full 10 percent and spend the other 90 torturing yourself because you know damn well that it’s far too late to make a drastic career change, and that you’re stuck on this mind-numbing path for the rest of your life.

Read the rest @ Find The Thing You’re Most Passionate About, Then Do It On Nights And Weekends For The Rest Of Your Life | The Onion – America’s Finest News Source.

Stephen Sparks blogs at Invisible Stories and co-curates Writers No One Reads and buys books for Green Apple Books at San Francisco. His blogs are a lifeboat for the eccentric, great, lost and ignored books, a growing book list to die for, an endless source of really good reading material, books with personality, the anti-consumer lit list.

dg

When I pick up the book—and I do, I do— I can, ten years on, detect a faint scent of cedar, a lingering reminder of the months I locked the book in a chest, hoping to later find it anew. I’m more inclined now to notice physical details, yellowing pages or a corner worn smooth by time, than the words contained between the book’s covers. We’re growing old together, the pair of us, ever-mysterious and unknown to each other.

Given this intimacy, it may not come as a surprise that despite my not-having-read-the-book, I nevertheless recommend it, based on… not false pretenses exactly, but a feeling that this book, the one I haven’t read but feel a deep affinity for regardless, deserves to be read—by others.

Wes Cecil is a great undergraduate teacher, an amazing classroom personality. And, of course, Wittgenstein is the greatest, most ill-understood philosopher of the last century or so, partly because he invented two quite different philosophical systems. He grew up rich in Vienna, in a suicidal family. Thomas Bernhard always leaned on the Wittgensteins in his novels for that very reason — brilliant, obsessed, suicidal characters; see, for example, his little book called Wittgenstein’s Nephew. I once went to see G. E. M. Anscombe lecture at the University of Chicago, not a public lecture but a class in a course she was teaching (November, 1967 or 1968). She sat behind a table smoking little black cigars and talking; this was the Wittgenstein style as I understood it. She was reputed to have held him in her arms as he died; this sounds romantic except that neither of them seemed to have been the slightest bit romantic. But I went to see her because of the legend. For years I was in love with the legend. There is a chapter on him in my M. Litt. dissertation buried in the University of Edinburgh Library.

Another thing that is interesting about Wittgenstein is of course that, though he was from Vienna (where they did either positivism or Freudianism), he learned his philosophy in England at the dubious hands of Bertrand Russell. He was in the tradition, more or less, of what was called analytic philosophy as practiced in the UK and America through most of the twentieth century. Analytic philosophy turned into linguistic philosophy at a certain point but always remained separate, almost hermetically sealed off from existentialism and phenomenology and later continental developments like deconstruction and the various forms of hybrid Marxism that came out of the Frankfurt School. The two (or three, depending on how you slice the potato) traditions look down their noses at each other most of the time. And nowadays analytic philosophy and even linguistic philosophy as it was once practiced is as dead as a doornail. So here I offer you a link to a new book about Wittgenstein and the uber-continentalist Heidegger; people are trying to bring them together (in my opinion, it can’t be done: Heidegger was a romantic in just the sense Wittgenstein was not; Wittgenstein was ever the anguished Puritan or the Viennese neurotic version of one).

.

dg

Here is an interview I did with Robert Coover in 1996 shortly after the publication of his novel John’s Wife. We were talking over the phone; the interview starts slowly as we feel each other out. But as it gathers steam Coover says marvelous things about his forerunners, Ovid, Kafka, Rabelais and Cervantes. He talks about how, when he planned the novel, he actually started with a paragraph count and the idea of a Bell curve. He also does a lovely reading of a passage — as he says, his first “telephone reading.”

This is from a raw tape that has been in a cardboard box for years; so my usual apologies for the sound quality.

Click the little triangular button to listen to the interview.

Coover Part 1

Coover Part 2

—Douglas Glover

See also interviews with Gordon Lish, John Hawkes & William Gass.

The Enemies of the Novel: DG Interview With John Hawkes

Causing Damage — Captain Fiction Redivivus: DG Interview With Gordon Lish

Limericks, Degraded Modernism and The Tunnel: DG Interview with William H. Gass

The extravaganza-by-the-lake continues. After reading in Port Dover Friday night (April 12), dg and Contributing Editor Sydney Lea, along with John B. Lee (multiple appearances in NC), will travel to Highgate for another event Saturday (April 13). Immense crowds are expected.

dg

The Mary Webb Cultural & Community Centre, 87 Main Street West in Highgate will be holding their second major poetry-reading-with-music on Saturday 13th April at 7.00pm. The evening, says Highgate-born author John B. Lee, is world class event. The line-up includes Authors John B. Lee, Poet Laureate for Brantford and for Norfolk, Marty Gervais, Poet Laureate for Windsor Sydney Lea, Poet Laureate for Vermont Douglas Glover, winner of a Governor General’s Award for fiction Musicians Ian Bell, Canadian folk musician, composer, singer-songwriter and recipient of a Queen’s Diamond Jubilee medal Michael Schatte, Chatham-born guitarist / writer whose lyrics have been published in a recent poetry anthology. All this in the warm acoustics of the historic former Highgate United Church, rebuilt in 1917. Audience members will have a chance to meet the authors and musicians – and it is hoped they will bring some of their publications for a book and CD signing. Tickets are $20.00 including light refreshments. Students are FREE

via POETRY & MUSIC at the MARY WEBB CENTRE, HIGHGATE | Entertainment | UR | Chatham Daily News.

The earth will tremble. Nothing short of that. The stars are in alignment. Sydney Lea once gave the best poetry reading dg has ever been privileged to witness. Three poet laureates! Not to mention that Port Dover is itself the scene of many youthful scrapes and escapades of dg’s youth which, happen the day, he may be prevailed upon to reveal at the event.

Ed. Note: Little known facts about Port Dover — In 1814 Americans came across the lake and burned the town; in retaliation Canadian and British troops went down and burned the White House (well, okay, it was mostly the British).

dg

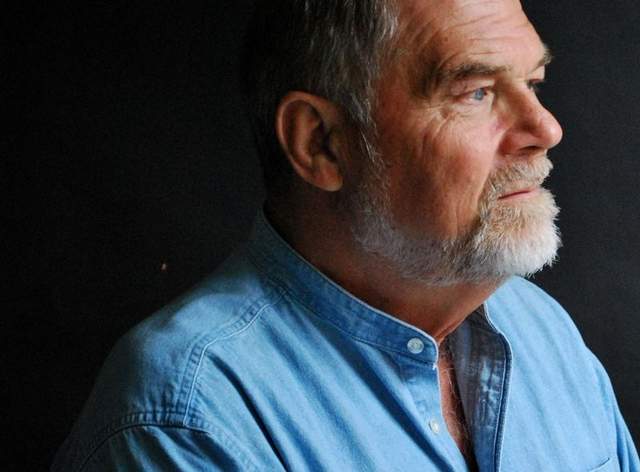

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub

Sydney Lea

Sydney Lea

John B. Lee

John B. Lee

Marty Gervais

Marty Gervais

Michael Schatte

Michael Schatte

A few of you have asked about dg’s mother’s hen, Annette, who at last report had moved into the farm kitchen after the other hens started attacking her. During dg’s visit to the farm last week, Annette was under foot, under the table and in the pantry, quite unperturbed by people and dogs. Well, she died Thursday night. DG’s mother, guessing that something was up, got a cardboard box, put the box on end so that the side was open, and made a nest of straw (normally chickens roost, only “nesting” to lay eggs). The chicken settled down in the box and only came out once after that. And in the morning she was dead. DG’s mother says, “I’ll never name another animal. If I get I dog, I’m just going to call it “dog.”

BTW, Jean is well past 90 and survived major cancer surgery last year and is still looking after the farm by herself. Here she is a couple of years ago, reciting a Walter Scott poem.

dg

Ground still frozen, huge trucks ferrying in loads of fertilizer. The tractor is just there for colour and to make nice circles in the snow. Old farming joke: Contrary to popular belief, plants don’t get nutrients from the soil. The soil is just to hold the plant down and then you pour fertilizer on it. These fields will be planted with canteloupes.

The next day it thaws. A pile of irrigation pipes sinking into a field of melt water.

The swamp at the back of the farm is the headwaters of a creek that eventually flows into Lake Erie, twenty miles away. This is precisely where the creek begins.

Cedar trees in a copse dg’s father used to call Hernando’s Hideaway (his reasons remain obscure but mysteriously romantic).

Wild turkey tracks, not to be confused with chickens (see below).

Chickens. Reminded DG of Culebra.

Sick chicken sleeping by the dishwasher in the farm kitchen. (The chicken’s name is Annette.) The chicken has moved into the house. It is like the pioneer days when people and farm animals lived together.

Chickens haunt dg’s dreams.

—dg

One of the postcards available at The Museum of the Emotions Store, a location in ASPHALT, MUSCLE & BONE – a film by bill hayward

One of the postcards available at The Museum of the Emotions Store, a location in ASPHALT, MUSCLE & BONE – a film by bill hayward

.

I love the synopsis of bill hayward‘s new film asphalt, muscle & bone.

A something restless and still, unexpected and empty. The morning launch moors at The Fat River Hotel landing. The Woman in Room 43 of The Fat River Hotel looks out the window of her room. The Man in Room 124 of The Fat River Hotel looks out the window of his room. There is dancing in the Ballroom of The Fat River Hotel. The daily delivery of bread and salt goes missing from The Hotel kitchen as soon as it arrives. A burnt world awaits the visitors to The Museum of Emotions. Radio traffic, letters and messages. Trees. Watchers. Wind.

But then, equally, you have to admire the haunting panache of the location titles: The Museum of Emotions, The Orchard of Burning Apples, The Plutonium of Incubation, Outlaw Lands where even God has not been — the words send a frisson of delight and anticipation down your spine. Bill is now posting scenes and script snippets online from time to time at his blog at billhayward.com — or as he says “scenes that may or may not be in the film.”

Visit hayward’s blog and be tantalized.

dg