In the mid-1990s I hosted a weekly literary radio interview show at WAMC-Albany (New York). One memorable morning over the studio phone, I interviewed Gordon Lish, whom I knew because he had published stories of mine inThe Quarterly as well as my novel The Life and Times of Captain N. (1993) at Knopf. The interview now appears in Conversations With Gordon Lish, edited by the estimable Cambridge (UK) critic David Winters and Jason Lucarelli, who was once a student of mine and contributing editor at Numéro Cinq Magazine. The book was published earlier this year by University Press of Mississippi in their wonderful “Conversations” series. The cover photo above is, of course, by NC contributor bill hayward.

—dg

Here is the publisher’s book description:

Known as “Captain Fiction,” Gordon Lish (b. 1934) is among the most influential–and controversial–figures in modern American letters. As an editor at Esquire (1969-1977), Alfred A. Knopf (1977-1995), and The Quarterly (1987-1995) and as a teacher both in and outside the university system, he has worked closely with many of the most pioneering writers of recent times, including Raymond Carver, Don DeLillo, Barry Hannah, Amy Hempel, Sam Lipsyte, and Ben Marcus. A prolific author of stories and novels, Lish has also won a cult following for his own fiction, earning comparisons with Gertrude Stein and Samuel Beckett.

Conversations with Gordon Lish collects all of Lish’s major interviews, covering the entire span of his extraordinary career. Ranging from 1965 to 2015, these interviews document his pivotal role in the period’s defining developments: the impact of the Californian counterculture, the rise and decline of so-called literary “minimalism,” dramatic transformations in book and magazine publishing, and the ongoing growth of creative writing instruction. Over time, Lish–a self-described “dynamic conversationalist”– forges an evolving conversation not only with his interviewers, but with the central trends of twentieth-century literary history.

This book will be essential reading not only for students and fans of contemporary fiction, but for writers too: included are several interviews in which Lish discusses his legendary writing classes. Indeed, these pieces themselves amount to a masterclass in Lishian literary language–each is a work of art in its own right.

Delighted and charmed also by the arrival of my author’s copy of Experimental Literature: A Collection of Statements, edited my Warren Motte and Jeffrey R. Di Leo. In it, you will find my essay “The Literature of Extinction.” The book is a special revised and expanded edition of American Book Review 37.5 (July/August 2016), where my essay originally appeared. It’s published by JEF Books, which is the book publishing wing of The Journal of Experimental Fiction.

I take particular pleasure in this publication in part because it cemented a friendship with Warren Motte, whom I met when I asked him to contribute to Numéro Cinq. Here is Warren.

Almost equally of importance is the fact that so many Numéro Cinq editors and contributors contributed to this book. Let me count the names: Douglas Glover (moi), Rikki Ducornet, Julie Larios, Michael Martone, Warren Motte (himself), Lance Olsen, and Eleni Sikelianos, This is a tribute to the sharpness of our cutting edge, the heft and depth of our community. I am pretty proud of this.

—dg

Here is the publisher’s description:

Literary Nonfiction. Essays. In EXPERIMENTAL LITERATURE: A COLLECTION OF STATEMENTS thirty-four writers and critics reflect upon how literature puts itself to the test in an effort to make itself new. Those reflections assume very different shapes, and each approaches the question from a different angle. There are formalist readings here, and historicist readings; some contributors consider the politics of literature, others focus upon aesthetics; some statements deal with national traditions or periods, others are more synchronist. There are pieces on French theater, the Russian avant-garde, and performance in West Africa. There are meditations on poetry as a daily practice, on experiment as a way of knowing, on the restlessness of liminal spaces, and on the incommensurate dimensions of dream and reality. Each contribution is fueled by the notion that literature works best when it is willing to interrogate its own premises. Both individually and collectively, these analyses display an extraordinary mobility, one that does justice to the dynamism of experimental literature itself. Each essay engages its readers actively and thoughtfully, inviting us to participate in a conversation about literature’s horizon of possibility, about what literature is and can be. Robert Coover, arguably the most distinguished living American experimentalist, contributes an afterword to this volume.

I am delighted and charmed to (drum roll) be able to say that I just received my author’s copies of Ingrid Ruthig‘s wonderful collection of essays David Helwig: Essays on his Works. I have mentioned this before on the blog, in the pre-order stage. Forgive me for repeating myself. It’s a lovely book. I mention in my essay an earlier essay by the late Tom Marshall, and Ingrid managed to snag the rights that essay and include it in the book. And so many Numéro Cinq alums had their hands in it, including Mark Sampson, rob mclennan and George Fetherling. And, of course, Ingrid herself published in the magazine (poetry and art). The book is published by Guernica Editions.

My essay “The Arsonist’s Revenge” on David Helwig‘s novella The Stand-in was commissioned by Ingrid especially for the book. I had a lovely time writing it. Helwig is a master of the novella form, also a master poet, novelist, memoirist — you name it. David is an old, old friend (inimitable) and also multiple contributor to the magazine. Not only that, but (have I mentioned this?) the book is stunningly good. Coincidentally (or not), the estimable and inimitable publishing house Biblioasis re-issued a splendid new edition of The Stand-in. You can buy a copy on the Biblioasis site or Indigo or Amazon.

—dg

My essay “The Arsonist’s Revenge” on David Helwig‘s novella The Stand-in will shortly appear in David Helwig: Essays on his Works edited by the inimitable Ingrid Ruthig (pub date is September 1 2018, but you can pre-order on Amazon.com or Indigo). Ingrid is a protean artist, contributing both poems and text/art to our pages (follow the links). In fact, she’s a prime example of how many people who found their way here actually became friends.

Ingrid subsequently, in her role as editor, invited me to write the essay for the book, which I was happy to do because David Helwig is an old, old friend (also inimitable) and also multiple contributor to the magazine. Not only that, but the book is stunningly good. Coincidentally (or not), the estimable and inimitable publishing house Biblioasis re-issued a splendid new edition of The Stand-in. You can buy a copy on the Biblioasis site or Indigo.

So, oddly enough, the magazine lives on (actually we still get upward of 600 views per day) in its influences and friendships.

dg

From the essay:

It’s a dramatic monologue, three lectures delivered extemporaneously by an unnamed retired humanities professor, a last minute replacement for the famous Denman Tarrington who has mysteriously succumbed the week before on the green-tiled floor of a hotel bathroom in New York. Our narrator has gone over the edge, abandoned circumspection and control; he has the podium, his ancient rival is dead (he and Tarrington were, for years, colleagues at the hosting institution), he will joyfully and maliciously set the record straight. Tarrington goes up in flames, demonstrated to be a plagiarist (he wrote his essays off the narrator’s ideas), a wife-beater, a compulsive and boastful seducer (the narrator’s wife ended up running away with him), and a flawed badminton player.

Buy the book to read the rest.

Audible has just (September 13) released the audiobook version of my novel Elle. This audio version is narrated by the replendent Severn Thompson who adapted the novel for the stage last year. Click the image above to go to Amazon and hear a sample of the novel.

Herewith, my introduction to Donald Breckenridge’s extraordinary new novel And Then just out with Black Sparrow, the venerable experimental/indie press now an imprint of David R. Godine in Boston. The introduction is included in the book and is reprinted here by agreement with Breckenridge and Black Sparrow/Godine. This isn’t a review; it’s an elucidation of the genius of form.

—dg

.

“We walk about, amid the destinies of our world-existence, encompassed by dim but ever present Memories of a Destiny more vast — very distant in the bygone time, and infinitely awful.” Poe, Eureka

Donald Breckenridge is a pointillist, constructing scene after scene with precise details of dialogue and gesture, each tiny in itself, possibly mundane, but accumulating astonishing power and bleak complexity. His language is matter of fact, the unsentimental plain style used subtly and flexibly. The only apparent artfulness is in the unconventional punctuation and, sometimes, the way the dialogue breaks up the narrative sentences. His settings are Carverish, bleak and constrained; his characters are the stubborn, alienated authors of their own melancholy fates; they persist in a panoply of failed habits and attitudes, gestures of a wounded self they refuse to give up because it is their own, a refusal that is by turns defiant, sordid, heroic, grotesque, and tragic.

But this novel’s triumph is in its rich architecture, its surprising splicing of genre and quotation, its skillfully fractured chronology, and the deft juxtaposition of alternating story lines. The result of this combinatorial panache is to create an arena of systemic implication, in which the sum is greater than the parts. Nothing here is what you expect; in fact, some of this text is nearly indescribable in terms of genre and form. What do you call a piece of fiction that is a narrative transcription of a real movie that is itself a fiction? Answer: Don’t even try. It’s a logical wormhole. It will turn your brain inside-out like a sock.

I will elucidate: And Then is, like most novels, a story about a character. Let’s say a nondescript loser robs a mom and pop store in some out of the way town and gives the money to his girlfriend so she can escape the mean and derelict provincial life she is destined for. She heads to New York with the cash, finds an apartment share, and has a love affair with a photographer, but the police (somewhere) are after her, and she falls among bad companions under the sign of hard drugs, who love her for her money. When that stake runs out, so does her string, and she disappears, probably dead, floating in the river.

But Breckenridge, the symphonic composer, takes this narrative theme, his melody, and works magic upon it by adding a half-dozen further elements.

1) A second, parallel plot involving a young male student who, a dozen years later, agrees to cat sit for one of his professors away on sabbatical. In the apartment he discovers the photograph of a beautiful woman, his professor’s mysterious former lover and/or roommate, a woman who simply disappeared. The student obsesses on the woman in the photograph; he becomes a sleuth, collecting stray bits of information about her. He finally tracks down the photographer who took the picture. But no one knows what became of her.

These two plots, the young woman plot and the student plot, leapfrog each other in the text, fragmented and uncanny. At a certain point the young woman, apparently waking from a drug stupor (only she is dead), finds her way back to the apartment, ascending the stairs just as the young student is descending. At the climactic moment, he feels her ghost passing through him.

2) An epigraph from Ionesco’s Present Past Past Present, an important influence for Breckenridge who takes epigraphs for all his novels from this text. The passage presents a character unfree, chained down, but conscious that he has the key to freedom, which he hardly ever uses.

3) An overture, or introductory passage, that consists of a prose transcription/narrative summary of Jean Rouch’s film Gare du Nord (1995, one of six short films by leading New Wave directors under the title Paris Vu Par). The film splits into two parts. The first follows a young married couple quarreling over the dissolution of their relationship; they are fed up with each other, disappointed in their mistakes, tired of their lives. In the second half of the film, the wife meets a handsome, brooding fellow who offers transcendence, offers her the chance to run away to a life of adventure. But she’s too bourgeois, timid, and polite to take him up. His response is to climb the bars of a railway bridge and jump to his death.

But what is going on? A novel disguised as a summary of a film? A quotation, as it were? A meta-commentary, or a work of art based on a work of art or in dialogue with a work of art? And the story itself is iconic, presenting the enormous ennui of modern life in the pressure cooker of a young marriage. But then the young man in the suit offers liberation. Is he a con, is he the devil, is he an angel? And the girl can’t contemplate running away from the life that is grinding her down. She hurries back into the trap. She doesn’t trust freedom — well, who would trust a man you had just met, who talks crazily about adventure, who looks too good in that suit? What is she going to do now? The message loop Breckenridge creates is convoluted and mysterious and yet firmly within a novel-writing tradition starting with Cervantes who, after all, wrote a great novel about a man trying to imitate another book.

4 & 5) The last quarter of the novel text is actually Donald Breckenridge’s brutal, sad memoir of his father dying: stark and beautiful and full of our common humanity; pity, love, kindness, stubbornness, squalor and valor. Here again there are two narratives: one works back and forth over the story of a life, two lives, father and son, and the father’s declining days; the other, more mysterious, follows Breckenridge to a diner, the subway, the train station. We get detailed accounts of conversations with the diner owner. We oscillate between donuts and staph infections, but by the genius of construction and understatement, horror and hopelessness accumulate. The word “love” isn’t thrown around, but the son patiently bandaging and dabbing medication on those awful sores tells you more than words. You are fascinated and cannot turn away.

Curiously, embedded in the memoir we find a scene in which Breckenridge tells his father about the suicide of a woman who lived in an apartment above him and how, he is sure, that one day he encountered her ghost in the stairwell. (The reader himself encounters a frisson of combinatorial delight.)

6) But even more curiously, embedded in the memoir we find also a few paragraphs in italics quoted from Théophile Gautier’s romantic horror story “The Tourist” (originally published as “Arria Marcella: A Souvenir of Pompeii” in 1852), a ghost story of sorts, in which a young traveler becomes obsessed with a woman’s figure preserved in the ash of Pompeii only to find himself translated that night to ancient Pompeii where he falls in love with the very woman. The story has the air of Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” or Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” The young traveler, sent back to his own time without the ghostly lover, never falls in love again, never fully engages with life.

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

.

And Then is beautiful, artful, an elaborated system of repetitions, motifs and juxtaposed narratives. Without wishing to be reductive, one can say that the three ghost stories relate to the theme of co-presence of temporal periods signaled in the Ionesco quotation, the way the past haunts existence. And they are balanced with three stories of characters who cannot change their behavior when change is the only way to redeem themselves (the young Parisian woman who cannot leave her job and marriage, the girl who runs away to New York with her stash, and Breckenridge’s father who cannot get himself the treatment that would save his life). And these in turn are refracted in three observer stories: the Brooklyn student who falls in love with photo of a missing woman, the youthful traveler in Gautier’s horror story, and Breckenridge watching his father die.

And Then is a contemporary ghost story, full of horror and unremitting melancholy, heir to the romantics, to Gautier and to Poe (yet also, stubbornly unsentimental in affect, reminiscent of the Nouveau Roman), a vastly literate work, engaged in its own conversation with the bookish past. Everything here is doubled and redoubled, echoed, mirrored, and reflected, and the dead do not die. The dead turn into ghosts or memories or words on the page, all of which are the same perhaps, at least in a book. And the effect in this novel is to create a mysterious intimation of a larger reference, a world beyond the book, a teeming yet insensible world that is yet no consolation.

.

.

I know that many of you envy the life of an internationally obscure writer, but I beg to remind you that sometimes there can be hazardous materials involved. Consequently, today I am modeling some DIY hazmat gear for the budget-minded author. Handy for wearing while reading reviews of your own work. This is not, as some of you might have waggishly opined, an erotic fetish costume, nor am I re-enacting a scene from an early Woody Allen movie. But I am on the farm in Ontario, and there is heroic work to be done. (I think I mentioned to some of you that I got the septic tank cleaned out two days ago — this has nothing to do with that!)

I also went to the grocery store, always a stirring experience, especially at sunset when the dear old Foodland parking lot is bathed in splendour.

Then I went to the woods to hunt for ramps. They are up, but we have so much ramp pesto from last year that it seems a shame to raid the beds again this year. And I forgot to take pictures of them. Anyone who wants to correct my identifications here can leave a comment.

Daffodils Jean planted here and there in the woods

Daffodils Jean planted here and there in the woods

Trout-lily or Dog-Toothed Violet or Adder’s Tongue

Trout-lily or Dog-Toothed Violet or Adder’s Tongue

Modern agriculture: You plant rye as a cover crop in the fall. It pops up in the spring. Then you spray a defoliant to kill the rye, disc up the land, and plant something new (the guys were out with the tractors today discing up this field). I took the picture a couple of days ago.

But then there is this.

—dg

My short story “Money” (first published in The Brooklyn Rail) just came out in the new 2016 edition (yes, seems a bit late) of Best Canadian Stories. Nice company, including Leon Rooke, Cynthia Flood and Elise Levine (we have a review of her new novel coming in the current issue).

Here’s a taste of the story. You can read it online at TBR, or get a copy of the book.

dg

Drebel started when he was fourteen organizing a grocery shopping service for the elderly in his neighborhood. He charged a flat rate per bag, accepted gratuities, and handled the cash exchange between the grocery store and the old people. Once he gained a customer’s trust, he would skim a percentage off the change, especially when the old man or woman couldn’t see that well. He would smile winningly while counting out the money; the old folks loved having a young person to socialize with. Seeing themselves reflected in his eyes, they thought they were smart, plucky oldtimers. Later, he was able to arrange a small quid pro quo from the supermarket manager’s petty cash to steer his customers away from competitors. He never bought bulk or generic. When an elderly party insisted on cheaper brands, Drebel would shrug and say the store was out. He watched for customers whose memory was failing and preyed on them, lifting a hundred dollar bill from the open purse or pocketing an expensive watch from the sideboard. Once he swiped a handful of silver cutlery from a drawer, sweeping it into his courier bag and clanking out the door. But he had trouble fencing the forks and spoons, and he was really only interested in the cash. He couldn’t help becoming fond of the old woman who said she would put him in her will, though he knew she wouldn’t. He didn’t take any offer of warmth or affection personally. He knew the old people were wrapped tight in their narrow lives, narrower and narrower as they grew older. They could be just as devious and mean as the next person. Drebel noticed how the codgers took a perverse pride in trying to shortchange him, arguing over the receipts, shaving the tip. “Here’s another quarter, son. Oh, drat. I thought I had another quarter. Next time?” He didn’t care. All he wanted was his cut, the skim.

Read the rest at The Brooklyn Rail.

I dunno. You don’t see this very often. But for today (March 27, 2017) Attack of the Copula Spiders as a double #1 on the Canadian Amazon site in the very strange “Canadian Literary History & Criticism” category.

But I’ll take it.

dg

Here’s a nice little note about my novel Elle by Eugene Mirabelli. Read the teaser below and click on the link to read the rest. This is a lesson in synchronicity. I was just talking to Michael Carson (a writer soon to appear on these pages) about Curzio Malaparte. I am rereading Kaputt, and Michael was extemporizing about La Pelle. And then Eugene shows up with a reference to La Pelle here.

Other aspects of this novel that set it apart are its fascinating surreal passages. Very few novels depicting historical events are also, in part, surrealist fictions. I recall a novel by Curzio Malaparte, La Pelle, that came out shortly after the second world war, a novel in which the real horrors of the war joined easily and smoothly with surreal passages. Douglas Glover makes similar moves in Elle, transitioning from the factual terrors of being marooned on a small island in a merciless Canadian winter to Marguerite’s hallucinations to the presence of a real magical bear – or maybe it’s a real bear.

By the way, the surrealism in Douglas Glover’s novel isn’t just another name for authorial invention. In an earlier brilliant and underappreciated novel, The Life and Times of Captain N., published back in 1993, the author presents a horrific vision of battles in Mohawk Valley during the American Revolution, but the nightmarish visions in that book are nailed to the commonplace world of human violence in realist fashion. In both novels, Glover mangles and distorts the facts to get at the truth.

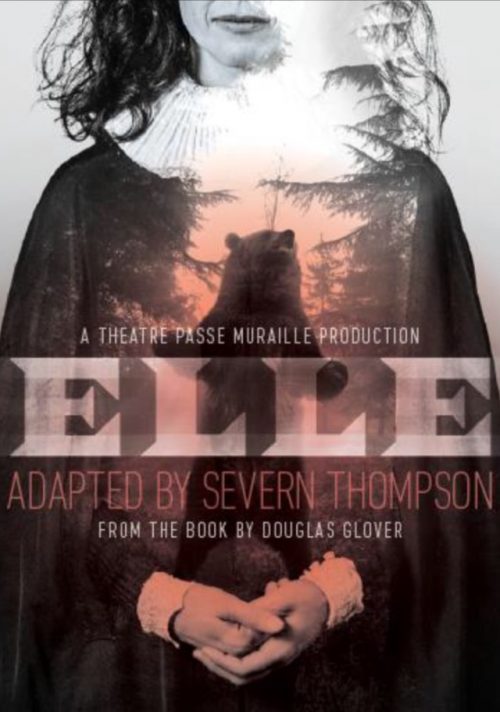

Here’s yet another news item out of Winnipeg where Elle, the play, is currently enjoying a three-week run (through to March 12).

The latest play at the Prairie Theatre Exchange is required viewing for anyone who wants to catch up on Canadian history usually shrouded in shadows. Elle is a touring production from Toronto-based Theatre Passe Muraille.

Severn Thompson stars as the titular character and Jonathan Fisher features in a supporting role. Thompson adapted the play from Douglas Glover’s 2003 novel of the same name.

“I discovered (the story) from a book in my grandmother’s bookshelf. It had won the Governor General’s prize, but I had somehow missed that in 2003,” Thompson said in an interview Tuesday.

“When I finally read it, it just was illuminating to me of a time in history that I thought was fairly – hmm, I don’t want to be rude – but fairly dull from my memory of early school days,” she said, laughing.

Source: Toronto play ‘Elle’ illuminates atypical colonizer-colonized roles | Metro Winnipeg

I have a new essay out in The Brooklyn Rail this morning, the upshot of an epic obsession, which has riddled my writing style with semicolons and taught me the value of plot triangles. Much gratitude to Wayne Hankey for his marvelous essay “Conversion: Ontological & Secular from Plato to Tom Jones (NC, July, 2014),” which introduced me to the word “kenotic” in regard to Fanny Price, to Laura Michele Diener, who taught me the meaning of “apophatic,” and to Jacob Glover for talking me through the ins and outs of absolutist ethics. You see, it was very much a Numéro Cinq co-production, though the obsession was all mine.

Here’s the closing section. Read the rest at The Brooklyn Rail.

What is truly paradoxical in Mansfield Park is the way it reaches beyond its satire on the marriage customs of Regency England, beyond the conventions of the romantic comedy, and beyond even its theological torque to tell a very modern story about the construction of a self. Much like Wolf’s Christa T., Fanny forges her self not in any positive way but in resisting imperatives, the forms imposed on her by her society and the gaze of the individuals around her. She is not simply a passive character; she is symbolic, fused with theme. I don’t want to, I can’t act, I won’t do that—Fanny Price’s refrain. She defines what action is by not acting. She defines morality by refusing to act.

The climax of Fanny’s non-plot is the sequence of scenes after the ball when she steadfastly persists in refusing to marry Henry Crawford. The fact that she cannot tell anyone that she loves Edmund, least of all Edmund himself, who is obstinately smitten with Mary, makes her appear irrationally stubborn. She remains cagey about her distrust of Henry. She can’t tell Sir Thomas about it at all; she confides in Mary (discreetly) and Edmund (explicitly), but Mary passes Henry’s flirtations off as harmless, and Edmund, too, minimizes Henry’s faults and suggests that time will prove his constancy (weasel words).

Above all, Fanny cannot escape their watchful, measuring eyes. Fanny is alternately cajoled, coerced, bludgeoned, and sent into exile, but she remains true to her principles. She is the poor, underclass cousin who has never stood up for herself before; but in these chapters she asserts herself against every authority, including the wishes of the man she loves. She even makes a speech (unique for Fanny) in which she enunciates what might be called the novel’s quintessential moral (in a novel full of moral discrimination).

“I should have thought,” said Fanny, after a pause of recollection and exertion, “that every woman must have felt the possibility of a man’s not being approved, not being loved by someone of her sex, at least, let him be ever so agreeable. Let him have all the perfections in the world, I think it ought not to be set down as certain, that a man must be acceptable to every woman he may happen to like himself. (292)

This speech reads like a feminist call to arms; those sentiments certainly existed. It asserts Fanny’s right of self-determination, and in the context of the novel, this radical selfhood stands against the ubiquitous dogma of property, propriety, income, estates, inheritance, class, and rank. By extension, it claims for any individual the right of refusal in the face of what the world offers. The basis of self is apophatic: the ability to say, I am not that, and I am not that either. What the world offers is contingent, mired in circumstance, calculation, and history, rated by pre-existing discourses (habits, traditions, forms). The soul proceeds by denial. Its struggle is less a matter of knowing itself as essence than of knowing when it is not itself. Sorting and discarding the trivia of life is the existential duty of the modern.

That Fanny (and the novel) can’t quite live up to this transcendent declaration is a sign of the tension that exists between Austen’s inspiration, the time in which she wrote, and her preferred genre, the romantic comedy. Fanny must marry Edmund Bertram despite the fact that as Edmund himself concedes, she is “too good for him.” Even the narrator is only dimly celebratory about the upshot.

With so much true merit and true love, and no want of fortune and friends, the happiness of the married cousins must appear as secure as earthly happiness can be.

This passage is sometimes construed as Austen’s ironic commentary on the romance genre or the institution of marriage. But we must wait another 150 years for a manifest critique of that ending in the form of John Fowles’s novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman in which the author offers readers the possibility, among others, that the disgraced, impoverished, abandoned female lead might continue to exist on her own and even prosper. When her lover finally appears after a gap of years, she remains cool, aloof – inviolable; she has her own life and no need of rescuing by a man.

First review from the Winnipeg run, and it’s good. Go Severn!

What makes it work as well as it does is that Thompson puts the narrative inside her heroine’s head. She comes to this new country with a completely inadequate dictionary of Indian words written by Cartier himself. By the time she meets a real native, an Inuit hunter named Itslk (Jonathan Fisher), she achieves equilibrium with him because he understands the woman’s new lexicon of dreams and visions as well as he happens to understand French.

The upshot of the play an be glibly summarized: You don’t inhabit the land; the land inhabits you.

But that would diminish the richness of the work, and especially of the character, brought to vivid life by Thompson’s performance, alternately comic, tragic, and bracingly primal.

Read the rest: Fight for survival in 1542 – Winnipeg Free Press

Here’s an interview with Severn Thompson, the actress and playwright who adapted Elle for the stage and who has made the role her own. This is in the venerable prairie newspaper, the Winnipeg Free Press. The play opens tonight at the Prairie Theatre Exchange and runs till March 12.

“She was somewhat rude and she had this impulsiveness. She had strong appetites, including sexual appetites, which get her into trouble,” Thompson says. “And like me, she resorts to humour when things get bad. That was one of her coping mechanisms and I just really appreciated that.

“She was shaped by the 16th-century aristocratic culture that she came from, but definitely lived on the fringes of it,” Thompson says. “She was a misfit.

“She had no interest in being a wife or a nun and those were the two options really available to her,” Thompson says. “In this account, she volunteered to go on this journey to see a new world. I don’t think she had plans to live there for the rest of her life. She wanted to have an adventure and see something she wasn’t familiar with.”She had no idea what she was getting herself into.”

Elle, the play, opens in Winnipeg at the Prairie Theatre Exchange tomorrow (February 23) night. I am told that tonight’s preview performance is sold out (upwards of 300 seats). Go Winnipeg!

This is the Theatre Passe Muraille production on tour. With Severn Thompson as Elle (she adapted the play from my novel) and Jonathan Fisher.

Some very nice poster art to go with the play.

Winnipeg performances run February 23 – March 12. Tickets and schedule here.

I don’t know Lincoln Kaye, but anybody who calls me a “CanLit superstar” is okay in my books and will no doubt find a special spot waiting for him in Heaven. The reviews coming out of Vancouver have been great, but this might be the best (and not just because he calls me a “CanLit superstar”). Here’s a quote. Follow the link below to read the rest.

And it’s as “Elle,” an unnameable, unimaginable “she”-bear, that she impossibly manifests in a Paris cemetery to maul to death the perfidious uncle decades after that ill-starred outbound Canadian voyage.

In Thompson’s commanding stage presence, all these “Elle” avatars nest within each other like Matryoshka dolls. Her body language and her stream-of-consciousness narrative slide fluidly backward and forward along the story-line, just like the text of CanLit superstar Douglas Glover’s novel from which Thompson herself adapted the script.

Read the rest of this scintillating review at the Vancouver Observer.

Here’s a generous and smart take on Elle, the play, from a critic and writer — Colin Thomas — who saw it the second night in Vancouver. I like the part where he says the audience was “deliriously appreciative.”

As if that starting point weren’t already thrilling enough, Glover and Thompson have wrought a magical realist telling of Marguerite’s story in which they explore—poetically and with great humour—themes of female sexuality, colonialism, and our spiritual relationship to nature. As Marguerite struggles for survival, killing birds and eating books, as she starves and hallucinates, as she rubs up against First Nations cultures and experiences the pull of a different world view, the shadow sides of patriarchy and colonialism gain force. Marguerite’s femaleness, her untamable libido, the relentless beauty of the wilderness, and her growing understanding of the fluid relationship between humans and animals, between waking reality and dreams; all of this pulls Marguerite apart and reshapes her. She has heard, vaguely, of a First Nations god, whose help she solicits—at a price. “One god guarantees my faith is true,” she says. “Two makes it a joke.” Marguerite begins to turn into a bear. “You cannot inhabit,” she says, “without being inhabited.”

The play’s language is as rich as its ideas—and it’s unpretentious. The fog off the coast is “as thick and oily as fleece.” “The smell of this new world is so fresh it has almost no smell at all.” And I mentioned humour. When Marguerite sees human footprints in the snow, she says, “A man was here. And now he is gone. I am suddenly not dead. It feels like a social life.”

More press out of Vancouver. Here’s a quote, Severn Thompson talking about the process of adapting the novel.

“It’s the story of survival that most of us missed in our history classes,” Thompson explained.

An admirer of historical fiction, the actor quickly saw the potential of showcasing Elle on the stage.

“It was very visceral and rude and funny in a way that historical fiction isn’t usually allowed to be, especially when involving women,” she enthused.

It took more than two years for her to adapt the work. Full of literary references and philosophical tangents, Elle is a complex book.

“That was the hardest part, really: whittling away at all these wonderful aspects of the novel,” Thompson said. “But the play hopefully brings it even more to life. From what I hear from people who see it, they feel spent but inspired by the end of the piece.”

Here’s a teaser from an interview Severn Thompson did with the Vancouver Sun.

Q: Elle opens with the main character engaged in what one review called “frantic fornication.” Was that also part of that early version?

A: Yes, with a chair. (Except for one other small part, Elle is a one-woman play, with Thompson occasionally using props). And he (Glover) came with his son. And my family was there too. I tried not to think too much about it.

Outside the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford

Outside the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford

The 2017 winter tour of Elle, the play, started in the Old Town Hall Theatre in Waterford, Ontario, January 26 – February 4. I’m a little reticent about the experience. More than I can translate into words. My ancient mother got to see the play for the first time (she remembered 2003, making the trip to Ottawa to see the Governor-General’s Award ceremony). My sons came on closing night. The play was better than a year ago. I thought I might be impervious, but it sucked me into the dream. There were standing ovations. There was a champagne reception. Keith Rainey came up to me after and I reminded him that when I was in Grade One, in the little stone one-room school house at Dundurn (eight grades in one room), he had played Bob Cratchit to my Tiny Tim in the Christmas concert. My father made me a crutch and a leg brace out of soup cans and old horse harness and we drank apple juice for wine and I got to say the words, “God bless us, every one!” My first brush with theatre.

dg

DG and Amber Homeniuk during the talkback after the last performance

DG and Amber Homeniuk during the talkback after the last performance

Taking pictures during the champagne reception after the show

Taking pictures during the champagne reception after the show

Top row l-r: Severn Thompson, Paul Thompson (legend of Canadian theatre, Severn’s father), dg, and Amber Homeniuk, master of ceremonies. Bottom row: Claire Senko, Old Town Hall Theatre artistic director, and Jonathan Fisher

Top row l-r: Severn Thompson, Paul Thompson (legend of Canadian theatre, Severn’s father), dg, and Amber Homeniuk, master of ceremonies. Bottom row: Claire Senko, Old Town Hall Theatre artistic director, and Jonathan Fisher

DG with multiple NC contributors Jonah Glover and Jacob Glover

DG with multiple NC contributors Jonah Glover and Jacob Glover

And here’s another review of the Vancouver production of Elle, at the Firehall Arts Centre till February 18.

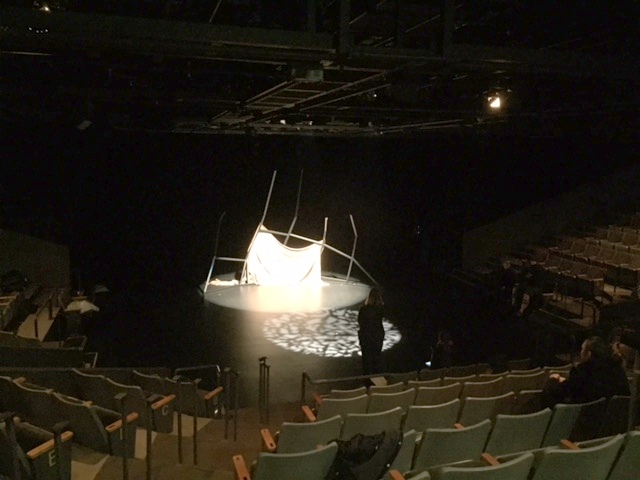

Thompson is a riveting performer with a rich voice and big emotional range, and director Christine Brubaker’s minimalist approach to the staging offers many pleasures. In Jennifer Goodman’s set, a structure of bent bars looms at the back of the stage, and a single piece of cloth becomes a sail, a hut, a fire, a bear cub, and so much more. Lyon Smith’s spare, otherworldly music is performed live by Jonathan Fisher, who also plays Itslk. And Goodman’s textured lighting enhances the magic-realist qualities of Elle’s story.

Delightful review of the Vancouver production of Elle, the play, at the Firehall Arts Centre. This is in Room, the fine and venerable feminist literary magazine.

dg

Playing Elle—who is something of an antihero, never without her flask—Thompson is a powerhouse from start to finish. Five minutes in and we see her energetically miming a sexcapade with her somewhat inadequate, tennis-obsessed lover, and from then on her energy (and healthy libido) hardly wavers. She delivers ninety minutes of vibrant, darkly funny text (it’s nearly a one-woman show) and though her character is desperately exhausted throughout, Thompson herself is not.

Severn Thompson as Elle via Now Magazine.

Severn Thompson as Elle via Now Magazine.

I’m a little slow on this. The story came out in December. But it’s a huge vote of confidence for Severn Thompson to add the to Dora Award nomination for Elle, the play, earlier in the year.

dg

You only had to watch Thompson, off to the side in a scene from Breathing Corpses, weep silent tears to realize how committed she is to her roles. She had a wider emotional scope in the terrific historic feminist script Elle, which she adapted as well as starred in. As talented a director as she is an actor, she co-created and helmed Madam Mao, which focused on another strong female character, and later directed a light, inventive staging of Peter Pan, set in various breweries around town.

Elle, the play based on dg’s novel, just opened in Vancouver last night at the Firehall Arts Centre after a two-week run in Waterford, Ontario. I was there. I have more to say but am processing. I saw the play several times last year when it premiered at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto. It was stunning then, better now. Mesmerizing, magical, mythic. Severn Thompson looks eight feet tall on stage. Subtle changes in the script and staging and music have clarified and strengthened the production.

But here is what The Georgia Straight had to say — more anon.

dg

It’s been almost 500 years since Marguerite de la Rocque de Roberval, a French noblewoman, was abandoned by her colonizer uncle, Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval, off the coast of Newfoundland. Her crime? Being a wild woman—the kind of wanton lady who dared take a lover on a transatlantic journey in 1542.

Her story of survival became the stuff of legend, and has inspired numerous artists over the years, including Canadian writer Douglas Glover. His book, Elle, a fictionalized account of de la Rocque de Roberval’s time marooned on the so-called Isle of Demons, won a Governor General’s Award, and it’s also the basis of Severn Thompson’s Dora Award–winning stage adaptation of the same name.

The Burning Air, Hutchinson, London, 1960

The Way In Viking, New York, 1968

No Resting Place Viking, New York, 1972

The World at Noon, Guernica Editions, Montreal, 1994

.

Eugene Mirabelli has written four novels which form a significant oeuvre. They are not singular, but interrelate in complex and delightful ways to form a unique (and, one assumes, unfinished) collectivity connected by a set of thematic concerns: family, marriage, Italian heritage, Cambridge, mutability and death; and structural articulations: the dominant male point of view that modulates briefly into the female at climactic junctures, the subtle fracturing and dislocating of time, and the interpolation of what Milan Kundera calls novelistic essays.

Literary comparisons are often invidious, but the names that come to mind as I read Mirabelli’s work are Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. The Burning Air is very much an Italian American “Goodbye, Columbus” and also reminds one of Bellow’s brief, tightly controlled early novels. Almost immediately, though, this comparison breaks down: Roth and Bellow share an era and a set of social concerns with Mirabelli, but their work falls into a Jewish American tradition (with roots in Yiddish literature) which is male-oriented, materialistic (i.e., of this world), intellectual, and comic. Mirabelli’s Italian American mental syntax is quite different: he builds his literary universe around an Augustinian dichotomy. His books are like long, careful sessions in the confessional, talking to God, enumerating small and large sins. His protagonists have one eye on the woman (wife and lover — Mary and Mary Magdalene) and one eye on death. He sees this world as an anxious and frustrating place, a place where his protagonists vain attempts at control are always being defeated by their own sinfulness and the fleeting nature of existence. Redemption comes only in the chaotic embrace of the family, the constricting yet reassuring bonds of love. A Mirabelli character may crack up and take anti-depressants, but one could never imagine him taking Roth’s detour into psychoanalysis or filing for multiple divorces as in Bellow.

Reading through Mirabelli’s novels in sequence one also begins to admire his technical ingenuity. He does lovely things which might not be noticed unless one treats the books as an on-going production. For example, he links his novels by taking a thematic note or plot segment from one and using it again in the next. The Burning Air is about a man who proposes to a woman and then never sees her again. In The Way In, the next novel, Frank Annunzio has proposed to a woman named Alba and then lost her. The Way In ends with Nancy’s premature and difficult delivery which is echoed darkly by Marianne’s miscarriage at the opening of No Resting Place. And, of course, Marco’s affair with Carol Crispin in No Resting Place is echoed in Nicolo’s affair with Roxanne in the last novel, The World at Noon.

Beginning with The Way In, Mirabelli also makes telling use of the novelistic essay. In The Way In, this takes the form of background essays on the Puritans who built New England and on the Shakers who built the school at which Frank begins his teaching career. The latter — mystical, other-worldly craftsmen — become a moral-spiritual counterpoint to the sad emptiness of Frank’s life before marriage and career. In No Resting Place, the device ramifies and extends itself into interpolated essays on Brook Farm, a running Sacco and Vanzetti sequence, and a tiny chapter on historic Albany. And in The World at Noon, the novelistic essay and family history combine and foliate in a delightful series of comic-mythic stories about the ancestors of the Cavallus. These interpolated essays and stories function like classical epyllions (one of Marshall McLuhan’s hobby horses) and give Mirabelli’s books what Yeats, in his essay on sub-plots in King Lear, called “the emotion of multitudes.”

This repetition of technical and thematic elements results in the odd sense one has reading these novels that the twenty-year gap between the publication of No Resting Place and The World at Noon ceases to exist in the experience of the reading. Mirabelli’s novels seem to form a perfectly logical sequence of growth, mutation and expansion. Each novel has been an advance in terms of technical virtuosity, thematic complexity and, for want of a better phrase, metaphysical accommodation. The Burning Air is taken up with George’s failed effort of control over the mysterious and fearful Giulia Molla. In The Way In, Frank Annunzio’s existential emptiness is the aftermath of that kind of loss of control (over women and/or the dark, shiftingness of things in general). Briefly, Frank is reprieved through marriage to Nancy and the community of friends he finds at the (Shaker) school (note especially the wonderful and redemptive chapter on kite flying), only to be plunged back into insecurity by the difficult birth of his child.

In No Resting Place, Mirabelli’s Manichean tour de force (the light of Brook Farm warring with the darkness of Sacco and Vanzetti), Marco Falconieri almost drowns in the slough of mid-life (and post-1960s) burnout which, really, is nothing but the final realization life itself will never redeem us, that things will not miraculously get better: “All our desire has been to carry through time, to stand on firm ground, reach out and stay the changes. Love leads us from ourselves to the things of this world, but in time these same things alter and pass away, no matter how much we cling to them. Here is no steady place.” In No Resting Place, Mirabelli grants us for the first time full access to the mental states of his protagonist as befits the overtly confessional mode of the narration. Mirabelli, as author, is himself beginning at this point to move deeper into his unique Italian-Catholic-American psyche, turning away from the vaguely modish, existential angst of the first two books toward a more chaotic (less controlled) vision of worldly and domestic uncertainty (the sinfulness of the flesh).

This is a dark, brave book which, in many ways, points toward its successor The World at Noon while yet not preparing us for the surprising shift of tone, the operatic and magical comedy of this most recent Mirabelli production. The World at Noon, as I have mentioned, replicates some of the plot articulations of No Resting Place — the extramarital affair, the reconciliation at the end. But the material is handled in a completely different way. It is as if, in delving always more deeply into who he is, Mirabelli has reinvented the peculiarly Italian, extravagantly melodramatic and often comic vision — the opera — in the novel form. By fusing the tale of American mid-life domestic woe with the mythical family histories of the Cavallus, he has created a wonderful interplay of now and then, this and that (the epyllion structure again). And he has coupled this complexity with a new sense of tranquil acceptance; not a superficial shrug but a genuinely comic (loving) accommodation. When Nicolo Pellegrino calmly invites his wife’s naked lover to climb down from the tree where he is hiding we know we have arrived at a totally new (for Mirabelli) and special literary place. And at the end of the novel, the double wedding of Gina and Aurora echoes the wedding at the close of The Tempest when Prospero throws his books of magic away and the world is renewed in the ritual sanctification of love and sexual regeneration.

—Douglas Glover

This essay originally appeared in Italian Americana Vol. 13, No. 2 (Summer 1995)

.

.

Here’s the new trailer for the Waterford production of Elle, the play based on my novel, which is actually the Theatre Passe Muraille touring production, bound later for Winnipeg and Vancouver. But the Waterford performance is first on the tour, my home town, champagne extravaganzas on the first and last nights. I will be there, possibly not standing upright.

In other news, it turns out Goose Lane Editions, Elle‘s publisher, is rolling out a new print run to keep up with demand. Nice news.

dg

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

Severn Thompson as Elle in the original Theatre Passe Muraille production.

More exciting news about Elle, the play (based in my novel Elle). If you have been tracking this you are aware that Severn Thompson and Theatre Passe Muraille are taking the play on tour this winter (tour details here). But it’s just been announced that this tour will actually start with performances in my home town of Waterford, Ontario, at the Old Town Hall Theatre, under the aegis of the most charming artistic director ever, Claire Senko (passionate, fierce, scarily competent, friend of Fred Eaglesmith).

I went over to meet Claire Friday afternoon and wander around the place. All strangely familiar because I grew up just outside of town, and once even strummed a guitar with my brother’s band during a rehearsal on the theatre stage in the early 70s.

There will be performances on January 26, 27, 28 and 29, and on February 2, 3, and 4.

There will be an opening night champagne gala and a talkback session with the playwright and actress Severn Thompson and Theatre Passe Muraille’s artistic director Andy McKim (who fed me incredibly intelligent questions about the novel and play when we did an onstage interview together last January).

And closing night (February 5, Saturday) there will be ANOTHER! champagne gala and a talkback session with me after the show. (Amber Homeniuk will be the facilitator, as they call it.)

dg

This video slideshow was produced by an old friend, Alison Bell. (Her brother Ian Bell has appeared in the magazine.)

DG and his intrepid close relative RG, who has appeared earlier on these pages, went for their usual pre-winter canoe trip on Big Creek (see Google map above: southern Ontario where Long Point juts into Lake Erie). RG fell in first unwisely trying to clear a snag. Then they went to another put in spot and realized they’d left the paddles back at the first put in. RG made DG stay with the canoe in the mud while he drove in his warm car (with heated seats) back for the paddles. DG, the creative mind behind NC, passed the time taking selfies. Then RG rammed DG into a thorn bush and his hand was bleeding. When they got back to the landing DG’s bare feet were so cold he fell over.

Actually, it was quite stunning (aside from the nature and brother-on-brother violence). Immense labyrinthine marshlands, many threatened species holding out there. Fascinating to me because in 1670, on Easter Sunday, two Sulpician priests, François Dollier de Casson and René de Brehant de Galinée, were struggling to cross Big Creek in flood when they heard above them the shrieks of horses, the jangling of harness, war cries and the sounds of battle. According to their journal, they knew exactly what it was, King Arthur’s Hunt. King Arthur’s Hunt is one name/a version of the legend of the Wild Hunt (also Charlemagne’s Hunt), which John Irving used in the short story “The Pension Grillparzer” in the The World According to Garp. Ghostly, wraithlike warriors riding and battling endlessly in the sky. Terrific to be in exactly that spot.

I have an anthology of quotations about Long Point and Norfolk County, including that journal entry, which you can read here.

dg

DG intrepidly negotiating hazard.

DG intrepidly negotiating hazard.

—Photos by dg, rg & google maps

Severn Thompson as Elle

Severn Thompson as Elle